Effective Practices for Implementing Quality Control Circles Aligned with ISO Quality Standards: Insights from Employees and Managers in the Food Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality Control Circles

2.2. Continuous Improvement Approach: PDCA

- Plan: Identify a problem or area for improvement, set objectives, and develop a detailed action plan to achieve desired outcomes.

- Do: Implement the plan on a small scale, testing the proposed solutions or changes.

- Check: Evaluate the results by comparing them against the objectives to determine whether the changes were effective.

- Act: Based on the evaluation, standardize successful changes or refine the plan further before broader implementation.

2.3. Quality Management Systems and ISO Standards

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Context

3.2. Employee Study

3.3. Management Study

4. Results and Discussion

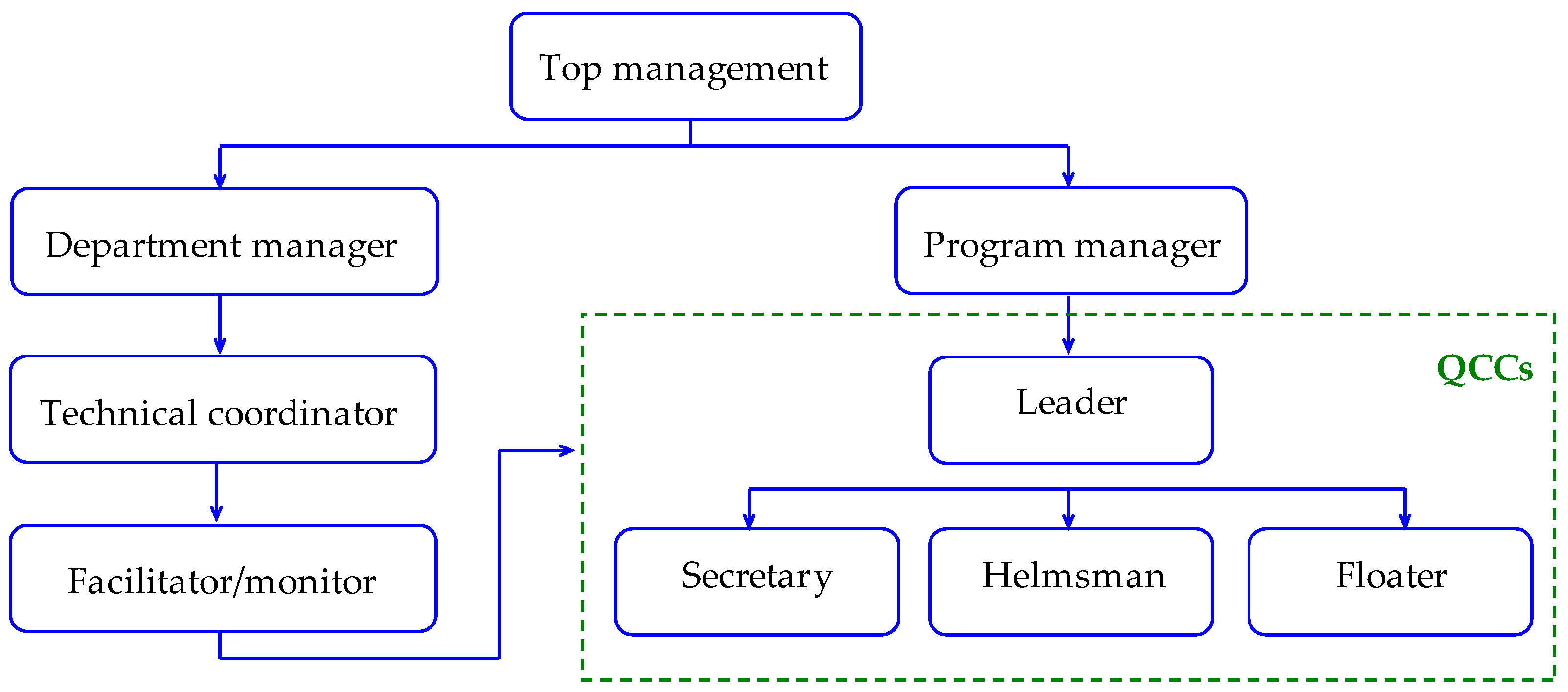

4.1. QCC Process Description

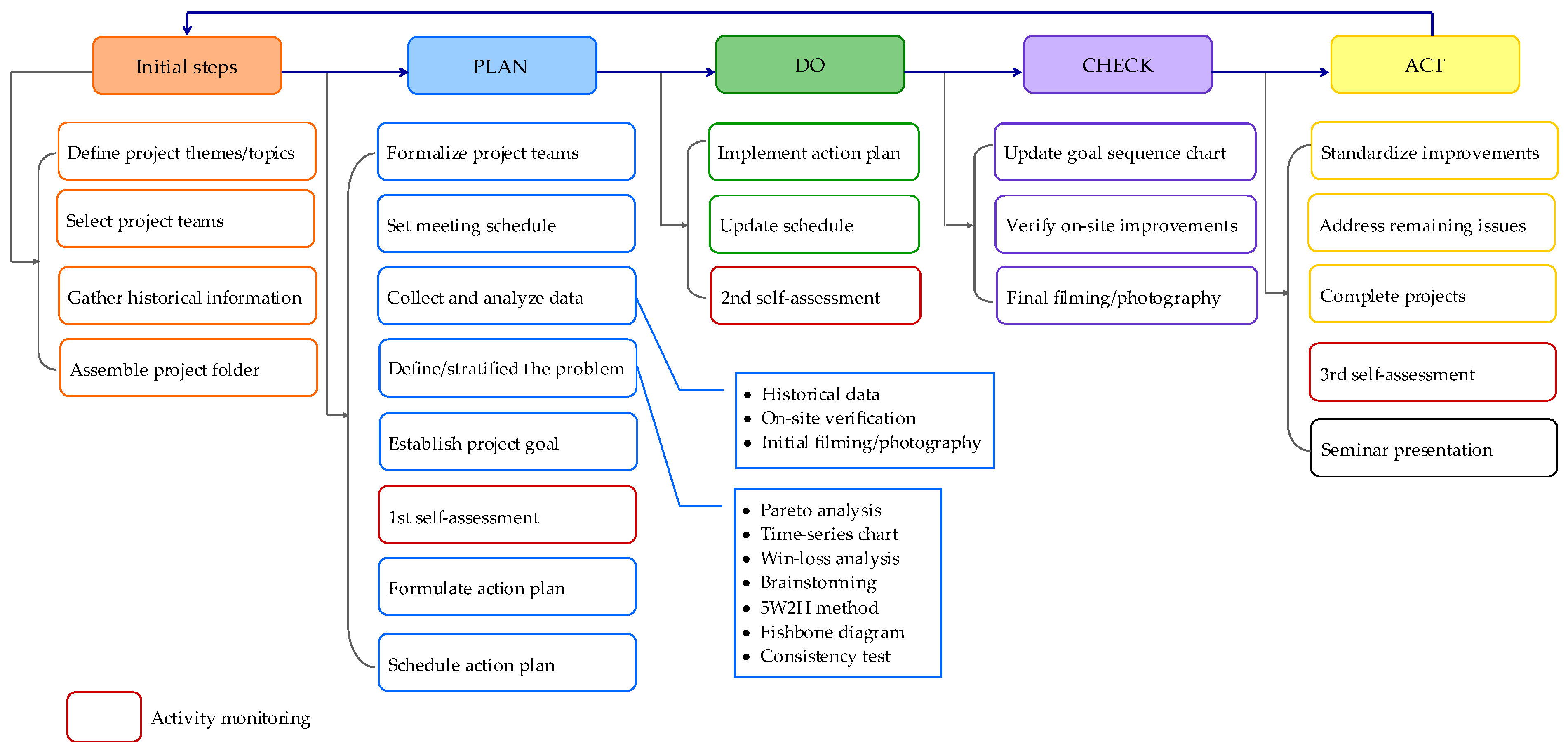

- Initial steps: The initial management steps involve recruiting activities and defining relevant topics. These topics are derived from management reviews, historical data, lessons learned from previous cycles, and internal suggestions. Voluntary groups are recruited and selected, followed by creating a project initiation folder that consolidates all this information.

- Plan: This phase lasts approximately two months due to the various steps involved. It begins with the formalization of groups, and this process is documented through a group certificate that includes the group’s name, members, roles, slogan, and team photos. This phase includes scheduling meetings to collect historical data (at least six months), perform on-site verification and validation, analyze available data, define and stratify the problem, identify causes and effects, and establish the project goal. Various analytical tools are employed during this stage, such as Pareto diagrams, time-series charts, win–loss analyses, brainstorming, the 5W2H method, fishbone diagrams, and consistency tests. Based on the analysis results, an action plan is developed to achieve the goal, and the plan’s schedule is formalized, marking the end of this phase. Notably, this phase involves continuous monitoring throughout its duration, along with self-evaluations to assess performance, stimulate self-critique, and reinforce the comprehension of the PDCA cycle.

- Do: This phase involves implementing the action plan, updating the schedule as needed to reflect ongoing activities or adjustments, and recording the results on the standard worksheet. The groups meet weekly for one hour in designated meeting spaces to advance their projects. Regular revision meetings or internal audits are held periodically as part of the monitoring process to evaluate progress, address execution challenges, and provide the necessary support during this phase.

- Check: Although periodic monitoring activities occur throughout all phases, the program manager oversees the progress at a macro level to evaluate the progress of all groups. This macro-level check includes reviewing the advancement and challenges faced by each group, inspecting and verifying planned activities on-site, collecting evidence of improvements, and creating control charts to visualize each group’s goal achievement progress.

- Act: Once the Do phase is completed, a final verification of the achievement of goals and expected results is performed. Standard worksheets are reviewed through self-evaluations, which help identify any remaining issues and standardize or update actions in standard operating procedures (SOPs). When standardization is implemented, all employees receive training on new or modified procedures, and a record of this training serves as evidence. Some groups may discontinue their work for various reasons. For instance, in the last cycle, out of the 23 groups, only 12 completed the cycle. The project folders of the groups were then archived by incorporating the lessons learned throughout the cycle. This phase concludes with a formal event in which groups present their projects to top management and department managers and outstanding performance is recognized through awards and acknowledgments. Even groups that do not complete the project are recognized with certificates acknowledging their participation in the QCC program.

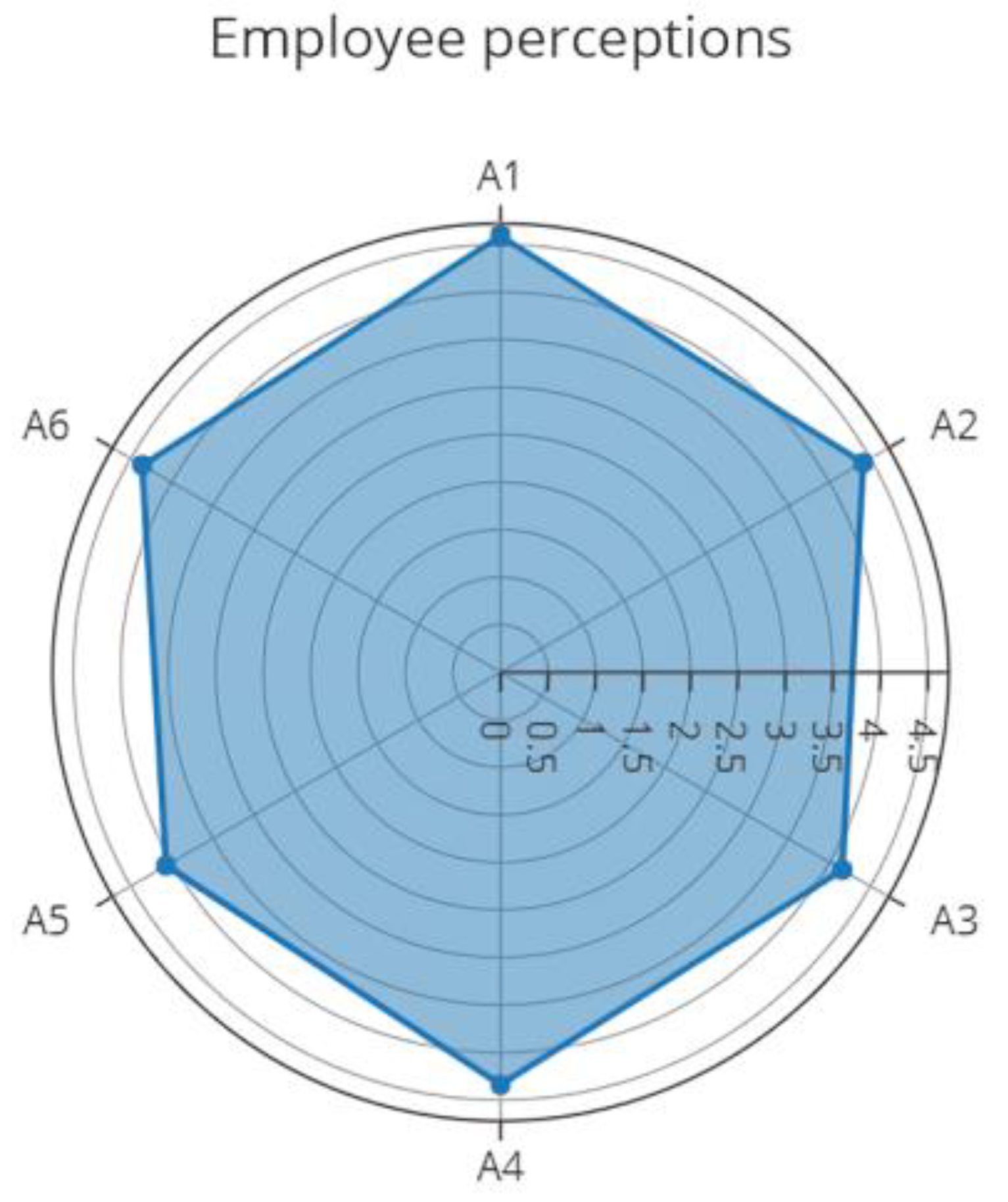

4.2. Employees’ Perception of the QCC Program

4.3. Program Management Perception of the QCC Program

4.4. Practical Insights for Enhancing the QCC Process

- Training and knowledge transfer: Effective training is crucial for the success of QCCs [10,12]. The case study, reflecting employee perspectives, highlights training as a critical issue for participants. Currently, only leaders and facilitators undergo training, with the expectation that they will transfer this knowledge to their respective groups. However, the results indicate significant deficiencies in this transfer of knowledge and inadequate performance of this responsibility. Since facilitators’ abilities and attitudes are pivotal to the effectiveness of QCC activities [10], organizations should implement comprehensive leadership training for leaders and facilitators, ensuring they have the necessary skills to train their teams. Continual improvement initiatives contribute to organizational learning and enhance knowledge when effectively integrated into management systems [21]. To support this, structured knowledge dissemination systems should be established, including scheduled training sessions and formal participation records. Furthermore, continuous monitoring is essential to ensure that all team members can proficiently apply the tools introduced during training.

- Resource allocation: Resource limitations are a well-documented challenge in the effective implementation of QCC initiatives [15]. In this case study, many solutions proposed by the QCC groups involve acquiring materials or equipment; however, budget constraints often impede their execution. This issue arises because costs are allocated to specific areas, and some areas lack the flexibility to fund projects that are not included in their initial budgets. Additionally, practical limitations, such as insufficient access to computers for group meetings, further hinder the documentation and progression of activities. To overcome these challenges, organizations should establish a dedicated budget for QCC-related projects, allowing for flexibility in funding unplanned activities. When additional resources are not feasible, organizations can explore more cost-effective solutions or optimize the use of existing resources, ensuring that group activities are not hindered by logistical constraints.

- Flexibility in QCC cycle duration and frequency: Proper time management is crucial for the successful implementation of quality control circle (QCC) initiatives [12]. Adjustments in the latest cycle of the case study include increasing the number of cycles from one to two per year, and suggestions are made to extend the duration of the final cycle beyond the usual timeframe. While some projects benefit from existing data, others require extensive data collection, which can extend project timelines. Additionally, the availability of team members for QCC activities is often limited due to other work demands. To address this, organizations should support effective timeline planning and allow flexibility based on the nature and priority of ongoing projects, as well as the need for periodic reviews and adjustments. For instance, in this case, extending the QCC cycle duration from three to five or six months is necessary. This extension will allow sufficient time for data collection, analysis, and solution implementation, ensuring a more thorough and effective process. Allocating and protecting dedicated time for QCC activities enables teams to concentrate on continuous improvement without the distractions of daily operational demands.

- Auditing and monitoring improvements: A key issue identified in the case study is the lack of adequate monitoring and verification mechanisms, which directly impacts the success of QCC efforts and their alignment with the QMS, particularly concerning ISO 9001 compliance. To overcome this challenge, organizations should focus on refining their auditing and monitoring processes. Audits should be strategically planned, ensuring that auditors have sufficient knowledge of the areas or projects being evaluated [35]. Providing additional training for auditors can significantly enhance their ability to accurately assess group activities and provide constructive feedback. Furthermore, monitoring mechanisms should be adapted to the specific needs of each project cycle, with flexible verification systems that can be adjusted based on lessons learned from previous cycles. This approach will help ensure that the expected goals and outcomes are consistently achieved.

4.5. Best Practices and Proposal for the Improved QCC Process

- 1.

- Establish clear objectives and guidelines

- 2.

- Provide comprehensive training

- 3.

- Ensure adequate resource allocation

- 4.

- Recognize and reward participation

- 5.

- Plan and monitor projects strategically

- 6.

- Standardize the use of tools

- 7.

- Integrate cross-functional teams

- 8.

- Conduct effective audits and evaluations

- 9.

- Use knowledge to drive continuous improvement

- 10.

- Communicate outcomes

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Recommendations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Theme | Clause/ Subclause | Description | Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning and Structure | 9001:2015 5.1.1 | Top management shall demonstrate leadership and commitment with respect to the quality management system by (d) ensuring that the quality policy and quality objectives are established for the quality management system and are compatible with the context and strategic direction of the organization. | The QCC objectives are clearly defined and aligned with the company’s objectives. |

| 9001:2015 7.1.2 | The organization shall determine and provide the persons necessary for the effective implementation of its quality management system and for the operation and control of its processes. | QCCs have a defined structure, including member roles and responsibilities. | |

| 9001:2015 7.2 | The organization shall, (c) where applicable, take actions to acquire the necessary competence and evaluate the effectiveness of the actions taken. | QCC members have received adequate training on the methodology. | |

| Procedures and Processes | 9001:2015 8.5.1 | The organization shall implement production and service provision under controlled conditions. Controlled conditions shall include, as applicable, (b) the availability and use of suitable monitoring and measuring resources. | QCCs use quality control methodologies and tools effectively. |

| 9001:2015 7.5 | The organization’s quality management system shall include (b) documented information determined by the organization as being necessary for the effectiveness of the quality management system. | There is adequate documentation of the processes and procedures used by the QCCs. | |

| 9001:2015 8.6 | The organization shall ensure documented information is available as evidence on the release of products and services. The documented information shall include (a) evidence of conformity with the acceptance criteria and (b) traceability to the person(s) authorizing the release. | The work processes of the QCCs are monitored and controlled according to documented procedures. | |

| Analysis and Improvement | 9001:2015 9.1.2 | The organization shall monitor the customers’ satisfaction, which is determined by the customers’ perception of the degree to which their needs and expectations have been fulfilled. The organization shall determine the methods for obtaining, monitoring, and reviewing this information. | QCCs are effective in identifying and analyzing quality problems. |

| 9001:2015 8.3.1 | The organization shall establish, implement and maintain a design and development process that is appropriate to ensure the subsequent provision of products and services. | There is a formal action plan to implement the actions proposed by the QCCs. | |

| 9001:2015 10.2.1 | When non-conformity occurs, including any arising from complaints, the organization shall (d) review the effectiveness of any corrective action taken. | The corrective and preventive actions recommended by the QCCs are implemented and monitored to verify effectiveness. | |

| 9001:2015 9.1.3 | The organization shall analyze and evaluate appropriate data and information arising from monitoring and measurement. | There is an evaluation system to measure the effectiveness of QCCs and the improvements resulting from their actions. | |

| Engagement and Communication | 9001:2015 7.3 | Persons doing work under the organization’s control are aware of (c) their contribution to the effectiveness of the quality management system, including the benefits of improved performance. | Employees are engaged and actively participating in QCCs. |

| 9001:2015 7.4 | The organization shall determine the internal and external communications relevant to the quality management system. | There is an effective flow of communication between QCCs and management. | |

| There is a recognition and reward system for the good performance of QCCs. | |||

| Learning and Risk | 9004:2019 11.3.1 | The organization should encourage improvement and innovation through learning. The inputs for learning can be derived from many sources, including experience, analysis of information, and the results of improvements and innovations. A learning approach should be adopted by the organization as a whole, as well as at a level that integrates the capabilities of individuals with those of the organization. | Top management practices learning about the implementation of QCCs based on group performance and recommendations from their members. |

| 9004:2019 11.4.3 | The organization should evaluate the risks and opportunities related to its plans for innovation activities. It should give consideration to the potential impact on the managing of changes and prepare action plans to mitigate those risks (including contingency plans) where necessary. | Top management assesses risks and opportunities related to innovation planning when implementing QCCs. | |

| The results of innovation in the implementation of QCCs are critically analyzed in order to foster organizational learning and knowledge. | |||

| Resource Management and Support | 9001:2015 7.1.1 | The organization shall determine and provide the resources needed for the establishment, implementation, maintenance, and continual improvement of the quality management system. | QCCs are provided with the necessary resources to perform their activities effectively. |

| 9001:2015 5.1.1 | Top management shall demonstrate leadership and commitment with respect to the quality management system by (g) ensuring that the resources needed for the quality management system are available. | There is visible and active support from top management for the implementation and operation of the QCCs. | |

| Integration with the QMS | 9001:2015 5.2.1 | Top management shall establish, implement, and maintain a quality policy that (d) includes a commitment to continual improvement of the quality management system. | The QCCs are aligned with the company’s quality policy. |

| 9001:2015 4.4 | The organization shall establish, implement, maintain, and continually improve a quality management system, including the processes needed and their interactions, in accordance with the requirements of this document. The organization shall determine the processes needed for the quality management system and their application throughout the organization and (b) determine the sequence and interaction of these processes. | QCCs work in integration with other areas and functions of the company to improve the quality of processes and products. | |

| 9001:2015 9.3 | Top management shall review the organization’s quality management system at planned intervals to ensure its continuing suitability, adequacy, effectiveness, and alignment with the strategic direction of the organization. | Top management conducts periodic reviews of the effectiveness of QCCs and their contributions to the quality management system. | |

| Documentation and Records | 9001:2015 7.5.2 | When creating and updating documented information, the organization shall ensure appropriate (a) identification and description (e.g., a title, date, author, or reference number); (b) format (e.g., language, software version, or graphics) and media (e.g., paper or electronic); and (c) review and approval for suitability and adequacy. | Adequate records are maintained of QCC activities and results. |

| 9001:2015 7.5.3.1 | Documented information required by the quality management system and by this document shall be controlled to ensure (a) it is available and suitable for use, where and when it is needed, and (b) it is adequately protected (e.g., from loss of confidentiality, improper use, or loss of integrity). | QCC documents and records are reviewed and updated as necessary to reflect changes and improvements. |

References

- Putri, N.; Yusof, S.; Irianto, D. Comparison of Quality Engineering Practices in Malaysian and Indonesian Automotive Related Companies. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 114, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatrix, M.; Triana, N. Improvement Bonding Quality of Shoe Using Quality Control Circle. SINERGI 2019, 23, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, H. Continuous Improvement Philosophy–Literature Review and Directions. Benchmarking Int. J. 2015, 22, 75–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veena, T.R.; Prabhushankar, G.V. Identification of Critical Success Factors for Implementing Six Sigma Methodology and Grouping the Factors Based on ISO 9001:2015 QMS. Int. J. Six Sigma Compet. Advant. 2020, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liao, M.; Liu, T. Implementation and Promotion of Quality Control Circle: A Starter for Quality Improvement in Chinese Hospitals. Risk Manag. Heal. Policy 2020, 13, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, I.; Azhar, T. Development of a Dynamic Model of Quality Control Circles: A Case of ABC Packaging Company. J. Manag. Res. 2020, 7, 288–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.A.; Álvarez, A.; Burciaga, S.; Durán-Muñoz, H.; Cruz-Domínguez, O.; Escobedo, J.; Rodríguez González, B.; Díaz, J.; Bermúdez, C. The Innovation of Quality Control Circles: A Clear Disuse in the Last 15 Years in the Mexican Industry. J. Bus. Res.-Turk 2019, 11, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinagaran, D.; Balasubramanian, K.R.; Sivapirakasam, S.P.; Gopanna, K. Workplace Safety Improvement Through Quality Control Circle Approach in Heavy Engineering Industry. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Mechanical Engineering (NCAME), Delhi, India, 16 March 2019; Kumar, H., Jain, P.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Kataria, K.; Luthra, S. Quality Circle: A Methodology to Enhance the Plant Capacity through Why-Why Analysis. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2020, 5, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yan, Y.; Liu, T.-F. Key Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Hospital Quality Management Tools: Using the Quality Control Circle as an Example-A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e049577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-R.; Wang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.-G. The Role of Quality Control Circles in Sustained Improvement of Medical Quality. Springerplus 2013, 2, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rohrbasser, A.; Wong, G.; Mickan, S.; Harris, J. Understanding How and Why Quality Circles Improve Standards of Practice, Enhance Professional Development and Increase Psychological Well-Being of General Practitioners: A Realist Synthesis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Kamath, R. Quality Control Circles: A Case to Import from Industry to Education. Indian J. Soc. Work 2004, 65, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcahyo, R.; Irhamna, O.; Dien, R. Effectiveness of Quality Control Circle on Construction Company Performance in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Bangkok, Thailand, 22–23 November 2018; IEEE: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A.; Agrawal, R.; Kumar Sharma, A. Green Quality Circle: Achieving Sustainable Manufacturing with Low Investment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadmann, S.; Holm-Petersen, C.; Levay, C. ‘We Don’t like the Rules and Still We Keep Seeking New Ones’: The Vicious Circle of Quality Control in Professional Organizations. J. Prof. Organ. 2019, 6, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syla, S.; Rexhepi, G. Quality Circles: What Do They Mean and How to Implement Them? Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 9004:2018; Quality Management—Quality of an Organization—Guidance to Achieve Sustained Success. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Watanabe, S. The Japanese Quality Control Circle: Why It Works. Int. Labour Organ. 1991, 130, 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Punnakitikashem, P.; Somsuk, N.; McLean, M.W.; Laosirihongthong, T. Linkage between Continual Improvement and Knowledge-Based View Theory. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 17th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Xiamen, China, 29–31 October 2010; pp. 1689–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.; Found, P.; Kumar, M.; Harwell, J. New Evidence on the Origins of Quality Circles. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, S129–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Lopez, L. Kaizen and Ergonomics: The Perfect Marriage. Work 2012, 41, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawesaengskulthai, N.; Tannock, J.D.T. Pay-off Selection Criteria for Quality and Improvement Initiatives. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2008, 25, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaouthar, L. TQM and Six Sigma: A Literature Review of Similarities, Dissimilarities and Criticisms. J. Manag. Econ. Stud. 2020, 2, 198–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.B.M.; Godinho Filho, M.; Fredendall, L.D.; Ganga, G.M.D. The Effect of Lean Six Sigma Practices on Food Industry Performance: Implications of the Sector’s Experience and Typical Characteristics. Food Control 2020, 112, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Cherrafi, A. Integrating ISO 9001 and Industry 4.0. An Implementation Guideline and PDCA Model for Manufacturing Sector. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2023, 34, 1629–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; Encarnação, J.; Gambôa, M.; Sampayo, M.; Jorge, D. PDCA 4.0: A New Conceptual Approach for Continuous Improvement in the Industry 4.0 Paradigm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, A.; Marinova, V.; Stoilov, D.; Kirechev, D. Food Safety Management System (FSMS) Model with Application of the PDCA Cycle and Risk Assessment as Requirements of the ISO 22000: 2018 Standard. Standards 2022, 2, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, G.K. An Innovative Approach to Make ISO 9000 Standards More Effective. Total Qual. Manag. 1998, 9, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backlund, A. The Definition of System. Kybernetes 2000, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceko, E. On Relations between Creativity and Quality Management Culture. Creat. Stud. 2021, 14, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A. InterContinental Review for Diffusion Rate and Internal-External Benefits of ISO 9000 QMS. Int. J. Prod. Qual. Manag. 2021, 33, 336–366. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaquen, J.; Carlos, M.; Norero, G.; Armas, H.; Pacheco, H. Quality in Private Health Companies in Peru: The Relation of QMS & ISO 9000 Principles on TQM Factor. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bravi, L.; Murmura, F. Evidences about ISO 9001:2015 and ISO 9004: 2018 Implementation in Different-Size Organisations. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 1366–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomba, M.Y.; Susol, N.Y. Main Requirements for Food Safety Management Systems under International Standards: BRC, IFS, FSSC 22000, ISO 22000, Global GAP, SQF. Sci. Messenger LNU Vet. Med. Biotechnol. Ser. Food Technol. 2020, 22, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, P.; Luo, L. Growing Exports through ISO 9001 Quality Certification: Firm-Level Evidence from Chinese Agri-Food Sectors. Food Policy 2023, 117, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.V.A.; Oliveros, T.V. Comparación del Desempeño Económico entre Empresas Industriales Alimentarias Certificadas y no Certificadas con la Norma ISO 9001. Ind. Data 2023, 26, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C.; Tsikriktsis, N.; Frohlich, M. Case Research in Operations Management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Culture Factor Country Comparison Tool. Available online: https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Forza, C. Survey Research in Operations Management: A Process-based Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 152–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F. Kruskal–Wallis Test. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19011:2018; Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Phillips, J.; Klein, J.D. Change Management: From Theory to Practice. TechTrends 2023, 67, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Label | Description | Mean | Median | Mode | Min | Max | SD | χ2 | df | p | ε2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Continuous Improvement | 4.59 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 0.497 | 0.367 | 1 | 0.544 | 0.008 |

| A2 | Productivity | 4.41 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.542 | 0.210 | 1 | 0.647 | 0.005 |

| A3 | Quality Culture | 4.16 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0.608 | 1.011 | 1 | 0.315 | 0.023 |

| A4 | Employee Engagement | 4.34 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.526 | 0.037 | 1 | 0.847 | 0.000 |

| A5 | Feedback and Recognition | 4.07 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0.728 | 0.066 | 1 | 0.797 | 0.001 |

| A6 | Employee Accountability | 4.36 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.613 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.916 | 0.000 |

| Category | Comment |

|---|---|

| Lack of resources | Lack of resources and little time to carry out planned countermeasures. |

| Investment and financial resources needed for improvements. | |

| Resources for development and deployment. | |

| Difficulty acquiring resources for effective results. | |

| Lack of resources, like more money, time, and people for implementation. | |

| Importance of time investment. | |

| Team engagement and availability | Difficulty getting everyone on the team together for meetings. |

| People being absent or unavailable due to production demands or sick leave. | |

| Lack of management organization for shop floor participation in meetings. | |

| Training and knowledge gaps | Lack of training in basic tools like spreadsheets. |

| Lack of understanding of methodologies like PDCA. | |

| Lack of training for facilitators. | |

| Not having the technical background before starting the project. | |

| Low level of team knowledge (paradigms). | |

| Resistance to change | Resistance to adopting new procedures and customs. |

| Difficulty convincing areas responsible for new processes. | |

| Barriers during implementation and understanding of the purpose. | |

| Communication issues | Difficulties in interacting with stakeholders. |

| Need for better communication and clarification for greater engagement. | |

| Neutral/no difficulties | Neutral view on involvement. |

| No difficulties faced or solved by the group itself. |

| Category | Comment |

|---|---|

| Implementation and planning | Increase the implementation schedule and receive more support from management. |

| At the end of each QCC cycle, the PDCA should be run again (continuous improvement). | |

| Training and development | Detailed training via the methodology. |

| Detailed training of the tool for all participants (leaders and others). | |

| Specific steps for QCC training. | |

| Improving the tool. | |

| Resource allocation and management | It only requires financial investment. |

| Put more qualified people in charge of auditing. | |

| Compliance with schedules and resources. | |

| Review and follow-up | Follow-up after the project to ensure continuity of the actions implemented. |

| It needs to be reviewed by staff with a different perspective. | |

| Over time, the project can gain even more visibility and better results. | |

| Organization and structure | Involve more people from the productive sector for practical learning. |

| Prevent the same employee from taking part in more than one QCC. | |

| Improvement in the organization of groups. | |

| There is always room to optimize an implementation. | |

| Visibility and communication | Wider and clearer dissemination of QCC and improvement groups. |

| Better planning with a more attractive sale of the project. | |

| Motivation and incentives | The prize is leisure time with the winner’s family and access to a park. |

| Neutral or unclear | Neutral (no further elaboration provided). |

| I can’t identify. | |

| Minor adjustments | Basic adjustment. |

| Small improvements in the implementation for the better adaptation of all. |

| Theme | Clause/ Subclause | Alignment with QCC | CP | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning and Structure | 9001:2015 5.1.1 | The QCC objectives are clearly defined and aligned with the company’s objectives. | 1 | The objectives are described in the program’s presentation and are directly based on the company’s indicators results, which, in turn, are related to the company’s strategic planning. |

| 9001:2015 7.1.2 | QCCs have a defined structure, including member roles and responsibilities. | 1 | In addition to the program structure, there is a formal structure of groups and their responsibilities. This information is made available to the improvement groups. | |

| 9001:2015 7.2 | QCC members have received adequate training on the methodology. | 1 | All facilitators and leaders receive training in the methodology and are multipliers of knowledge to their respective groups. | |

| Procedures and Processes | 9001:2015 8.5.1 | QCCs use quality control methodologies and tools effectively. | 1 | The groups undergo audits during implementation, of which one of the objectives is to adjust and guide the use of the tools. Therefore, at the end of the cycle, the use proves to be effective. |

| 9001:2015 7.5 | There is adequate documentation of the processes and procedures used by the QCCs. | 1 | There is a standard implementation schedule spreadsheet used by all the groups. | |

| 9001:2015 8.6 | The work processes of the QCCs are monitored and controlled according to documented procedures. | 1 | During the implementation schedule, there are audits to check and monitor the work processes as established. | |

| Analysis and Improvement | 9001:2015 9.1.2 | QCCs are effective in identifying and analyzing quality problems. | 1 | The audits also serve to guide the identification and analysis of the problems listed by the groups. |

| 9001:2015 8.3.1 | There is a formal action plan to implement the actions proposed by the QCCs. | 1 | There is an action plan structure within the standard spreadsheet provided. | |

| 9001:2015 10.2.1 | The corrective and preventive actions recommended by the QCCs are implemented and monitored to verify effectiveness. | 0 | Actions are monitored indirectly through company indicators. Not all topics have a direct indicator for this verification. | |

| 9001:2015 9.1.3 | There is an evaluation system to measure the effectiveness of QCCs and the improvements resulting from their actions. | 0 | The improvements are monitored through the indicators, and the effectiveness check is not yet well developed; however, the groups themselves monitor their results so that adjustments can be made as necessary. | |

| Engagement and Communication | 9001:2015 7.3 | Employees are engaged and actively participating in QCCs. | 1 | The participation rate of the groups during the schedule is monitored. In the last cycle, the groups achieve a participation rate of over 60%. |

| 9001:2015 7.4 | There is an effective flow of communication between QCCs and management. | 1 | The audits are used to give feedback to the groups, and the results of the forms are sent to the managers. Communication media are also used to promote this flow of communication. | |

| 9001:2015 7.4 | There is a recognition and reward system for the good performance of QCCs. | 1 | Each cycle has a different reward system. All participants receive certificates, and the two best groups receive a technical visit. | |

| Learning and Risk | 9004:2019 11.3.1 | Top management practices learning about the implementation of QCCs based on group performance and recommendations from their members. | 1 | There is a practice of top management learning based on the performance of the groups. When these groups achieve and improve performance indicators, such as setup and scan time reduction, the company revises the standards, considering the new targets achieved. |

| 9004:2019 11.4.3 | Top management assesses risks and opportunities related to innovation planning when implementing QCCs. | 0 | Opportunities are regularly discussed at meetings, but there is no formal, structured risk assessment. | |

| 9004:2019 11.4.3 | The results of innovation in the implementation of QCCs are critically analyzed in order to foster organizational learning and knowledge. | 1 | All results are monitored by indicators, and they evolve through performance and group participation. | |

| Resource Management and Support | 9001:2015 7.1.1 | QCCs are provided with the necessary resources to perform their activities effectively. | 0 | Resources such as laptops are not provided directly (as it is understood that at least one of the members has one). Nor is there a fee for the groups to carry out the improvements. All the necessary costs are included in each sector’s cost center. |

| 9001:2015 5.1.1 | There is visible and active support from top management for the implementation and operation of the QCCs. | 0 | There are still difficulties in providing resources. | |

| Integration with QMS | 9001:2015 5.2.1 | The QCCs are aligned with the company’s quality policy. | 1 | The company’s quality policy involves the following topics 1—Complying with legislation and process requirements 2—Partners/suppliers as an integral part 3—Continuous evaluation 4—Attitudes and values 5—Customer satisfaction Therefore, it is understood that the QCCs meet all five requirements described in the company’s quality policy. |

| 9001:2015 4.4 | QCCs work in integration with other areas and functions of the company to improve the quality of processes and products. | 1 | In essence, the groups are cross-sectoral, and the members are chosen strategically so that different areas that impact the subject can contribute to the proposed improvement. | |

| 9001:2015 9.3 | Top management conducts periodic reviews of the effectiveness of QCCs and their contributions to the quality management system. | 1 | At the end of each cycle and implementation, meetings are held to discuss the results. Therefore, revisions are made. | |

| Documentation and Records | 9001:2015 7.5.2 | Adequate records are maintained of QCC activities and results. | 1 | The records of the groups during implementation are kept in virtual folders, and there is also a record of the history of implementation over the years in the company. |

| 9001:2015 7.5.3.1 | QCC documents and records are reviewed and updated as necessary to reflect changes and improvements. | 1 | Every cycle is reviewed and evaluated based on the results obtained and the performance/engagement of the groups so that improvements can be proposed and implemented. | |

| Compliance rate | 78.26% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima, A.B.S.d.; Becerra, C.E.T.; Feitosa, A.D.; Albuquerque, A.P.G.d.; Melo, F.J.C.d.; Medeiros, D.D.d. Effective Practices for Implementing Quality Control Circles Aligned with ISO Quality Standards: Insights from Employees and Managers in the Food Industry. Standards 2025, 5, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5010006

Lima ABSd, Becerra CET, Feitosa AD, Albuquerque APGd, Melo FJCd, Medeiros DDd. Effective Practices for Implementing Quality Control Circles Aligned with ISO Quality Standards: Insights from Employees and Managers in the Food Industry. Standards. 2025; 5(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Ana Beatriz Silva de, Claudia Editt Tornero Becerra, Amanda Duarte Feitosa, André Philippi Gonzaga de Albuquerque, Fagner José Coutinho de Melo, and Denise Dumke de Medeiros. 2025. "Effective Practices for Implementing Quality Control Circles Aligned with ISO Quality Standards: Insights from Employees and Managers in the Food Industry" Standards 5, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5010006

APA StyleLima, A. B. S. d., Becerra, C. E. T., Feitosa, A. D., Albuquerque, A. P. G. d., Melo, F. J. C. d., & Medeiros, D. D. d. (2025). Effective Practices for Implementing Quality Control Circles Aligned with ISO Quality Standards: Insights from Employees and Managers in the Food Industry. Standards, 5(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5010006