1. Introduction

In this study, the authors aim to address critiques surrounding the operational efficiencies in humanitarian logistics, particularly within the United Nations (UN) context, motivated by the observation that applying dynamic capabilities, commonly associated with the commercial sector, may offer significant potential within the UN. Exploring this observation is crucial for further contribution to the field of supply chain management, especially in the unique context of humanitarian operations. Moreover, there is a recognized gap in the existing literature regarding the application of the DCT, specifically in the context of supply chain management within the UN. Therefore, researchers aspire to provide actionable strategies that can enhance the supply chain management practices with a focus on the UN. The ultimate goal is to contribute positively to the efficiencies of the UN operations.

Although supply chain management has been extensively explored in academic literature, there remains a significant gap in the application of dynamic capability theory to humanitarian supply chains. Existing research predominantly focuses on commercial supply chains, thereby neglecting the complex, volatile environments inherent to humanitarian operations. This study addresses this gap by investigating how dynamic capabilities can be effectively adapted and leveraged within humanitarian supply chains, providing both theoretical advancements and practical implications for improving operational efficiency in such critical contexts.

The literature review uncovered notable gaps that serve as the base for this study. Firstly, critical gaps exist in the form of cross-cultural studies on supply chain systems. Additionally, a significant gap is identified concerning the impact of dynamic capabilities on pre-disaster performance, with most of the literature focusing on post-disaster performance. Therefore, this research seeks to contribute unique insights into proactive strategies. Furthermore, the literature review reveals a disproportionate emphasis on humanitarian logistics and NGOs compared to the UN. So, this study bridges the gap by centering on the UN, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how dynamic capabilities can be leveraged for effective supply chain management within this distinct context.

In this study, the authors addressed the following research question: What strategies do executive supply chain managers of the United Nations use to leverage operational performance? To address this research question, the authors implemented a qualitative method approach by engaging with the UN supply chain managers through interviews to acquire their in-depth experiences and views. Participants served in various peacekeeping missions of different geographies. Therefore, to explore differences between cases and to replicate findings across cases, the authors applied multiple case studies, allowing them to analyze within each setting and across settings [

1].

The UN supply chain managers become involved in large-scale humanitarian crises. Therefore, they have a purposeful aim to establish international peace, security, and development. Relief programs may address the issues of political instability, military conflicts, civil warfare, famines, and natural disasters. Donors providing financial support expect humanitarian and peacekeeping interventions to improve the challenging situation effectively and efficiently in the affected places. The humanitarian community has been criticized for lacking coordination, collaboration, and operational efficiencies [

2].

Moreover, donors’ budget constraints intensify the pressure to improve disaster management logistics and find strategies to perform humanitarian supply chains efficiently [

3]. Although the supply chain concept has defined best practices to ensure efficiencies, humanitarian supply chain managers need an entrepreneurial approach and understanding of dynamic capabilities to address disruptions and instability in the business environment and meet ever-changing customers’ needs [

4]. Moreover, unforeseen humanitarian disasters such as the latest pandemic are causing significant shifts in supply chain systems, thus requiring a proactive approach with solid, efficient strategies to enhance responsiveness in humanitarian crises.

Humanitarian supply chains are under pressure to deliver their programs efficiently due to 75% of supply chains experiencing disruptions [

5], accounting for 60 to 80% of the expenses due to limited funding and increasing scrutiny by donors [

6]. Humanitarian operations are inextricably linked to the performance and functioning of a supply chain. If humanitarian supply chain managers fail to understand and adopt dynamic capabilities, they can experience operational underperformance and failure, affecting trust from financial supporters. This qualitative multiple-case study aimed to explore strategies that executive supply chain managers of the United Nations (UN) use to leverage operational efficiencies in a peacekeeping program.

2. Literature Review

The literature review includes dynamic capability theory (DCT) as the conceptual framework, humanitarian supply chain, innovation capabilities, supply chain analytics, big data predictive analytics (BDPA) in the supply chain, knowledge management capability, information technology, leadership, relational capabilities, coordination and collaboration, risk management, agility, resilience capabilities, and sustainability in the supply chain management.

2.1. Conceptual Framework: Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT)

The dynamic capabilities theory forms the theoretical foundation of this study, providing a lens through which to understand how supply chain managers within humanitarian organizations like the UN respond to volatile and unpredictable environments. The theory emphasizes the importance of sensing, seizing, and transforming capabilities, processes that are crucial for adapting to the complex and rapidly changing conditions faced in humanitarian operations [

7]. In this study, dynamic capabilities are explored through the strategies used by UN supply chain managers to enhance operational performance, such as the application of data analytics, leadership, and risk management. These capabilities enable organizations to reconfigure resources and processes in ways that improve both efficiency and resilience in high-stakes environments.

The importance of organizational management is crucial in recognizing problems and trends, redirecting resources, reshaping structures, realizing new opportunities, and addressing them [

7]. Therefore, the DCT highlights three processes. The first process is “sensing”, which includes selecting new technologies, encouraging innovation, and identifying target market segments. The second process refers to seizing opportunities that embrace new business models, avoiding biases, and setting organizational boundaries. The third process manages threats and reconfiguration activities through changing business structure and knowledge management.

Using DCT, managers can identify opportunities, formulate a response, and reconfigure in ever-changing and disruptive times [

8]. The supply chain managers of the UN operate in fragile and unpredictable places. Therefore, it was expected that supply chain managers could use DCT to delineate their strategies by focusing on change management and contemporary knowledge-based management, resulting in a competitive advantage.

The dynamic capabilities framework is robust. The concept integrates different perspectives and capabilities that can help recognize the need for ongoing actions to build, reconfigure, and extend the organizational resource base [

9]. Conclusively, with dynamic capabilities, managers can compete in an unstable business environment and meet changing customers’ needs [

4].

2.2. Humanitarian Supply Chain and DCT

To address emergencies effectively, the UN acts together with other stakeholders, such as commercial enterprises, host governments, donors, military forces, local communities, logistics service providers, and international and local nongovernmental agencies. Each may have different motivations, modus operandi, culture, mandates, resources, and technical expertise, thus adding complexities in the humanitarian context [

10,

11]. Prasanna and Haavisto [

11] highlighted the importance of culture in such a dynamic environment. They continued that a lack of cultural sensitivity and incompatibility may result in inefficient coordination among humanitarian actors, leading to failing aid delivery. According to Prasanna and Haavisto [

11], organizational culture presents the foundation of a successful humanitarian supply chain. Dubey et al. [

12] posited trust as the critical enabler of the coordinated humanitarian operation participative environment.

Numerous actors involved in humanitarian logistics response add to operational complexities and require clarity on achieving effectiveness. Therefore, Wilson et al. [

13] presented a framework reflecting cost, responsiveness, resilience, security, sustainability, and innovation as the key drivers and how an appropriate balance between each element may result in desired expectations in emergency logistics. Although the supply chain’s central pillar is to respond “faster, better, cheaper”, inherent trade-offs require strategy-driven considerations [

14]. For example, quick operations contribute to responsiveness but usually negatively affect the cost. More broadly, Wilson et al. [

13] linked these drivers to emergency logistics practices, collaboration, and outcomes, resulting in a more coordinated humanitarian supply chain management design.

To assist the population in crisis, the UN supply chain managers should ensure a seamless flow of suitable materials and services from the point of origin to the right end-user. This activity encompasses a series of aligned processes: demand planning, acquisition, transportation, track and trace, warehousing, and client satisfaction.

Natural and human-made disasters are increasingly causing disruptions in people’s lives beyond their ability to control and cope [

12]. Therefore, humanitarian organizations engage in relief programs to help affected populations, especially in developing countries with inadequate infrastructure, political instability, uncertainties, and challenging operational environments. Sherwat and Ebrashi [

15] identified four humanitarian operations steps: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. The last step differentiates the short-term transitional phase from the long-term recovery phase. The long-term recovery phase often involves various humanitarian programs for peace establishment, healthcare, education system development, and food aid to return the lives of victims to normality. In the humanitarian context, provision for supply chain planning and execution may suffice during the recovery phase. The recovery phase is costly and requires significant resources [

15]. Jahre [

16] argued that planning appears at every stage, including preparedness involving network design and warehouse locations.

2.3. The UN and DCT

Humanitarian organizations, including the UN, are applying a dynamic approach to deliver aid and fulfill their mandate efficiently. Therefore, Sherwat and Ebrashi [

15] explained that sensing capabilities include beneficiary assessments by collecting data on demographics in the humanitarian context. Azmat and Kummer [

17] also added information on required needs and logistics. The required needs entail the volume of the affected population, vulnerabilities, and damage level. The latter usually includes information on infrastructure, transportation capacity, or distances between operational hubs. The availability of this information determines decision-making and, eventually, overall supply chain performance.

Natural and human-made disasters are increasingly causing disruptions in people’s lives beyond their ability to control and cope [

10]. Therefore, humanitarian organizations, including the UN, engage in relief programs to help affected populations, especially in developing countries with inadequate infrastructure, political instability, uncertainties, and challenging operational environments. Sherwat and Ebrashi [

15] identified four humanitarian operations steps: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. The last step differentiates the short-term transitional phase from the long-term recovery phase. The long-term recovery phase often involves UN programs for peace establishment, healthcare, education system development, and food aid to return the lives of victims to normality. In the humanitarian context, provision for supply chain planning and execution may suffice during the recovery phase. The recovery phase is costly and requires significant resources [

15]. Jahre [

16] argued that planning appears at every stage, including preparedness involving network design and warehouse locations.

The UN humanitarian operation is increasingly under pressure, and strict scrutiny from donors requires efficient overall performance. Fadaki et al. [

18] highlighted that some humanitarian organizations focus on fundraising instead of operational efficiencies and effectiveness. The latter humanitarian supply chain managers are becoming result-oriented, improving transparency and accountability, ensuring value for money, and developing a robust performance measurement system to ensure continuous funds flow from donors [

17]. Nevertheless, Dubey et al. [

12] continued that historically, humanitarian supply chain operations have been considerably behind their commercial counterparts in operational efficiency and effectiveness due to the high bureaucracy and decreased recognition and understanding of humanitarian logistics functions. Consequently, the absence of logistics in budgetary processes did not allow for meeting logistics requirements. Today, supply chain managers demonstrate that a successful supply chain is crucial in delivering the UN mandate. Moreover, humanitarian supply chain managers can have something to teach their commercial colleagues, including ways to quickly respond to changing and challenging environments.

2.4. Innovation Capabilities

Innovation capability is an essential factor in organizational success. Aslam et al. (2020) defined it as the willingness to introduce novelty through creative processes to develop new products and services. Sabahi and Parast (2020) described innovation as applying new ideas, skills, methods, and knowledge, thus creating distinctive advantages. Kwak et al. [

19] and Chege et al. [

20] posited that innovation occurs within processes, technologies, services, strategies, and organizational structures to improve the corporate value chain by eliminating obsolete operations. Parast [

21] posited that researchers’ focus on innovation increased by 235% over 20 years and continued that innovation is venturing into unknown territory, searching for new opportunities and possibilities for growth, and bringing problem-solving ideas into use. Conclusively, researchers studied innovation in the supply chain from different perspectives. Invention through technology facilitates information sharing, which is crucial for efficient coordination among logistics members and adequate resource deployment [

11]. Next, innovation is extensively evaluated and found necessary to allow organizations to respond rapidly to changes in customer demand [

19]. Last, Sherwat and Ebrashi [

15] investigated how innovation may generate multiple funding sources in social entrepreneurship.

2.5. Supply Chain Analytics

There are multiple definitions of supply chain analytics. Shamout (2019) explained supply chain analytics as the complex processing of past and present data through quantitative tools and techniques, therefore, a combination of IT-enabled resources, data management, and supply chain planning. As a result, firms create resilience capabilities and strategies. Supply chain analytics includes data extraction, cleaning, integration, and transformation into meaningful patterns for decision-makers. Therefore, the proper control of logistics flow enabled by analytical capabilities is vital for substantial humanitarian and peacekeeping performance (Moshtari & Gonçalves, 2017). Gupta et al. (2018) posited that analytical capability is the critical organizational capability defined by managerial skills, technical skills, and organizational culture that results in competitiveness. The supply chain analytics is expected to grow from 4.8 bn USD in 2019 to 9.8 bn USD in 2025, potentially increasing by 13.68% between 2017 and 2021 [

22].

Supply chain analytics brings multiple benefits to the business. Mikalef et al. [

23] posited that big data analytics could decrease the acquisition cost by 47% and enhance the revenue by 8%. Shamout [

24] explained that supply chain managers gain valuable insights through analytics. Through analytics, supply chain managers can also identify errors and develop strategies to reduce these errors, reduce costs, reduce risks, improve responsiveness, resource allocation, process integration, reduce duplication of resources, and enhance operational capability and efficiency [

12,

24]. Fosso and Akter [

22] found that supply chain analytic capabilities improve supply chain agility by providing complete diagnostic information, sensing external factors, forecasting demand, and controlling variability in demand and cycle times. Shamout [

24] highlighted that supply chain analytics enhance innovation, which is essential for organizational sustainability. Singh and Singh [

25] elaborated on visibility as vital in supply chain management because it directly impacts real-time consumer demand and adequate inventory planning. Moreover, in circumstances of high uncertainties, high visibility increases the willingness of humanitarian supply chain managers to share their resources. Conversely, unwillingness to share information or inability to integrate information systems among partners reduces visibility.

Analytics is mainly based on information and communication technology. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the related challenges.

The objective of using big data analytics is to improve the supply chain analytic capability. Big data analytics is a holistic process involving the 5Vs (volume, velocity, variety, value, and veracity) in the context of data collection, analysis, use, and interpretation [

22]. Dubey et al. [

12] defined big data predictive analytics (BDPA) as the combination of tangible resources encompassing physical and financial resources and intangible resources such as employees’ skills, knowledge, IT tools, and processes. Mikalef et al. [

23] defined big data analytics capability as the ability of the firm to capture and analyze data to create insights and evidence to support transformation. In their research, Dubey et al. [

12] found a significant influence of BDPA on visibility and coordination among humanitarian actors. Similarly, Mikalef et al. [

23] argued that BDPA could enhance dynamic capabilities and lead to innovation, a data-driven decision-making culture, identification of new business opportunities, and, eventually, high performance.

2.6. Business Performance Management in Humanitarian Supply Chain

Shamout [

24] argued that BDPA could improve supply chain performance by improving visibility, resilience, and robustness. Moreover, Agarwal et al. [

6] posited that a performance measurement system is becoming an essential requirement from donors because it provides the data to ensure resources, improve accountability, and establish operational efficiencies and effectiveness. However, humanitarian operations still lack a robust measurement system and exclude beneficiaries’ perspectives [

26]. Dubey et al. [

12] emphasized the importance of metrics standardization for the global assessment of humanitarian organizations. In this context, Agarwal et al. [

6] suggested a balanced scorecard for measuring performance and the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) for evaluating the overall health of humanitarian supply chain management.

2.7. Knowledge Management Capability

Supply change managers in organizations must promote knowledge management capabilities to survive a turbulent and ever-changing environment. Developing and sharing new practices can improve performance in the long term and its survival, growth, stability, and competitiveness [

27]. Therefore, Breznik et al. [

28] argued that organizations must build dynamic capabilities by adopting new, upgrading existing knowledge, and transforming it into solutions. This argument aligns with Lyra et al. [

29], arguing the importance of knowledge diversity as a decisive success factor. Aslam et al. [

4] emphasized a learning culture that allows rapid knowledge gathering and seizing new opportunities.

Knowledge sharing may bring considerable advantages to supply chains. Huo et al. [

30] articulated some benefits applied to the manufacturing sector. These benefits include inventory reduction, cost reduction, enhanced visibility, reduced uncertainties in demand and supply, rapid response to clients’ needs, improved track and trace, reduced replenishment time, and optimized capacity utilization. Sikombe and Phiri [

31] explained the need to create, share, and disseminate knowledge to materialize the benefits. However, Sangari et al. [

32] refined knowledge management processes into six steps. First, knowledge creation implies knowledge sourcing within and outside the organization. Second, knowledge capturing includes new knowledge development, which should be continuous. Third, knowledge organization requires information filtering, its usefulness identification, and modeling. Next, knowledge storage includes data warehouses in an efficient format and data access security. Fifth, knowledge dissemination is the process of knowledge exchange. Last, through knowledge application, managers’ ideas get into action, resulting in desired efficiencies.

2.8. Information Technology in Supply Chain Management

Information technology (IT) is restructuring all aspects of businesses and making the world globalized [

33]. According to Yu et al. [

34], companies continuously invest in IT to achieve competitive advantage by applying cost-effectiveness and multifaceted approaches. Breznik et al. [

28] and Kwak et al. [

19] added that IT facilitates innovation and improves products, services, strategies, and processes, thus enabling dynamics in business activities and acting as a critical factor in economic growth. Furthermore, according to Breznik et al. [

28], deploying dynamic capabilities, especially technological capability, is crucial for innovating profitability and changing the organizational structure. Yu et al. [

34] investigated the impact of IT capabilities on supply chain integration. They found a significant positive relationship showing the immense value of IT capabilities in supply chain management. Khalil and Belitski [

35] urther discussed the importance of the IT governance mechanism in integrating and reconfiguring internal and external resources in a dynamic digital environment. Internal resources encompass digital capabilities and skills within the firms, while external resources are acquired through information sharing using digital tools to enhance information and resource management. Zeraati et al. [

36] thoroughly elaborated on strategically important knowledge gained from external resources and translated it to the organization’s needs.

2.9. Leadership in Humanitarian Supply Chain Management

Managers are critical components in developing dynamic capabilities. Breznik et al. [

28] explored managerial abilities within a dynamic capability framework. Therefore, they grouped managerial capabilities into sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities and elaborated extensively on each managerial capability. For example, managers with effective communication skills can sense opportunities inside and outside the firm. Similarly, open-minded managers who embrace diversity and build trustworthy long-term partnerships have seizing capabilities [

37]. Therefore, Breznik et al. [

28] suggested that managers take an active role in sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring dynamic capabilities and leading by example.

Moura et al. [

38] explained that in humanitarian organizations, leaders must manage the resources from donors considering the impact of political and economic circumstances. Furthermore, humanitarian organizations consist of regular employees and volunteers whose leaders should manage them differently. Volunteers’ motivational components could be stronger compared to those of employees. Therefore, leaders should know how to enhance motivation, manage expectations, and maintain high efficiency and effectiveness. L’Hermitte et al. [

39] added that humanitarian supply chain managers manage the network of interconnected stakeholders.

Therefore, leaders should manage the supply chain from a global perspective. There are barriers associated with leadership. According to Bealt et al. [

40], these barriers include structural, mandate, and behavioral barriers. Structural barriers include poor governance, accountability, and inadequate resources. However, mandate barriers emerge when members are not committed to tasks and activities. Similarly, Bealt et al. [

40] elaborated on the lack of authority, competencies, and skills as behavioral barriers. Breznik et al. [

28] compared positive and negative managerial practices in different areas, such as strategic orientation implementation, organizational structure, organizational culture, managerial capabilities and leadership, human resources, and continuous knowledge transfer and absorption. Managers may use it as guidance in realizing the implications of their managerial actions. Chen and Kitsis [

37] added that developing strategic capabilities takes commitment from top management and requires time and respect for cultural diversity and natural systems.

2.10. Relational Capabilities in Supply Chain

Building strong relationships is essential in supply chain management due to the increasing geographic dispersion of customers, suppliers, and service providers. Prasanna and Haavisto [

11] described a relationship as a degree of closeness between and among the organizations. Fragmented relational practices such as communication, collaboration, information sharing, trust-building, process integration, collaborative performance system, and risk management combined create relational capabilities and result in uplifting performance, sustainable outcomes, and a competitive advantage [

41,

42]. To interconnect the mentioned relational practices, the commitment of top management is imperative.

Relational capabilities have been extensively researched through the lens of relational view theory. The relational theorists argue that an organization can generate relational rents and gain higher performance against uncertainties if managers invest in relational capabilities. Collaborative capabilities are considered the most effective in deploying resources and developing competencies, processes, and structures addressing potential risks [

43].

In the humanitarian context, organizations often compete over resources, donors, and local networks, thus discouraging them from investing in collaborations. Similarly, a high level of uncertainty additionally creates barriers to inter-organizational interactions [

44]. Bealt et al. [

40] further explained thatunderstanding the culture will help overcome those barriers, while enhanced performance measurement will allow visibility, detect gaps, and identify adequate relational practices. In this context, Friday et al. [

41] analyzed collaborative risk management, including the following capabilities to mitigate risks: risk information sharing, standardization of procedures, joint decision-making, benefit-sharing, process integration, and collaborative performance systems.

2.11. Coordination and Collaboration in Humanitarian Supply Chain Management

Relational cap-bilities entail collaborations and coordination among supply chain partners and are the principal element of successful sustainability practices. Chen and Kitsis [

37] posited that relational capabilities developed through collaborations are difficult to imitate, thus presenting a key source of competitive advantage. Additionally, sustainability-based collaborations rooted in trust, commitment, shared values, and common vision are prerequisites and outcomes of collaborations [

37].

Extensive research has shown that collaboration is necessary at every stage of the supply chain, including planning, procurement, and transportation. Prasanna and Haavisto [

11] explained collaborations through being relationship-focused and process-focused. The former entails close and long-term relationships, while the latter is based on supply chain actors’ processes to achieve the common goal. Prasanna and Haavisto [

11] elaborated on elements leading to collaborative behavior: trust, mutuality, information exchange, communication, and commitment. In a humanitarian context, stakeholders often need to exercise effective coordination because beneficiaries are placed in the program’s center [

3]. In the context of humanitarian operations, collaborations are essential.

Complex relief programs require collaboration and coordination on all levels. A degree to which supply chain partners collaborate Torabi et al. [

45] called supply chain integration and further evaluated supplier integration, customer integration, external integration, and internal integration. Adem et al. [

46] elaborated on types of partnerships in humanitarian organizations, including private businesses and contracts with host governments, the military, or NGOs. The former are fast-moving and action-oriented, while the latter are bureaucratic and slow. Najjar et al. [

26] further elaborated on relationships between employees and refugees as crucial for the propensity of the shared information. Moshtari and Gonçalves [

44] differentiated horizontal and vertical relationships in this context. The vertical includes parallel collaboration with suppliers and customers, sharing responsibility, resources, and information. Conversely, horizontal relationships include collaborations with competitors to increase efficiency and reduce costs.

2.12. Trust among Humanitarian Supply Chain Partners

Trust among supply chain partners is one of the essential resources. Trust motivates engagement in social interactions and is critical in long-term relationships [

37]. Prasanna and Haavisto [

11] posited that a lack of trust might result in rivalry. Additionally, mutuality and reciprocity can help to build trust too. Wilson et al. [

13] and Najjar et al. [

26] highlighted that trust and established social capital should enhance the reliability of information shared among partners and willingness to share. Developing swift trust is essential in humanitarian and relief operations because swiftly formed global team members must work together toward a common goal [

10]. However, Bealt et al. [

40] argued that the humanitarian community does not necessarily trust the good intentions of the private sector, while private organizations perceive humanitarian organizations as overly bureaucratic. Nevertheless, investing in inter-organizational trust and developing bonding skills lead to positive collaborative relationships [

10].

2.13. Risk Management in Supply Chain

There are many definitions of risks. Aslam et al. [

4] described risks as phenomena preventing routines and decision-making patterns; therefore, something to be managed and avoided. In the supply chain context, Friday et al. [

41] defined supply chain risk management as an inter-organizational collaborative effort to identify, evaluate, mitigate, and monitor unexpected conditions that might impact the supply chain. Fischer-Preßler et al. [

47] explained risk identification as the process of determining the potential threats. Risk reduction includes measures reducing risks, while risk monitoring is a continuous audit function assessing the risk-reducing measures. In all phases of risk management, Fischer-Preßler et al. [

47] highlighted the contributing role of IT.

Researchers have explored various methods for successful risk management. Friday et al. [

41] concluded that effective technology utilization, efficient leadership, teamwork, and communication would enhance visibility, establish a risk management culture, and mitigate disruptions. Such a digital supply chain is driven by the Internet of Things, Big Data Analytics, Cloud computing, ERP systems, RFID technology, barcoding, and additive manufacturing solutions. Fischer-Preßler et al. [

47] explored the role of IT in risk reduction more profoundly and posited that organizations intensively invested in IT solutions in the last two decades.

2.14. Resilience Capabilities in Humanitarian Supply Chains

Many researchers have tried to articulate supply chain resilience through different definitions. Parast [

21] posited supply chain resilience as a dynamic capability that helps firms respond to and recover from disruptions. A simple definition originated by Chowdhury and Quaddus [

48] indicates that supply chain resilience is the organizational capability to survive in a turbulent environment. Chowdhury et al. [

42] explained resilience as the capability of the supply chain to develop readiness, response, and recovery to manage risks, thus ensuring the return to the original state or even better after disruptions. However, Mackay et al. [

49] explained resilience as the ability to prevent and resist events and return to an acceptable level of performance in an adequate time.

Recent studies demonstrate extensive research on the relationship between innovation and resilience. Sabahi and Parast [

50] found that innovative firms are more resilient to disruptions because innovation fortifies capabilities that positively affect risk management. Precisely, capabilities mediating the relationship between innovativeness and resilience are knowledge sharing, agility, and flexibility. Similarly, Golan et al. [

51] argued that innovation generates positive risk management capabilities and elaborated on smart solutions, blockchain, and artificial intelligence to maintain agility and increase resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The efficiency in measuring resilience is essential for managers to improve performance and sustain competitive advantage. Therefore, Chowdhury and Quaddus [

48] developed and validated hierarchical and multidimensional scales for measuring supply chain resilience. Similarly, in their research, Singh and Singh [

25] examined the effect of big data analytics on business risk resilience. They found that adopting big data analytic capability will allow transparency, sound decision-making, accountability, and innovation, enabling them to develop supply chain resilience effectively. Consequently, the ability to address risks adequately leads to an efficient supply chain and increased performance.

2.15. Supply Chain Sustainability

Sustainable supply chain management is a vital phenomenon. Chen and Kitsis [

37] explained a sustainable supply chain as crucial for integrating business operations and sustainability, thus resulting in reduced risk and improved performance. Chen and Kitsis [

37] defined a sustainable supply chain as managing material, information, and capital flow through the chain intending to achieve economic, environmental, and social goals. Similarly, Shan et al. [

52] defined sustainable supply chain management as integrating and realizing the supply chain’s economic, environmental, and social objectives.

Understanding the goals of supply chain sustainability is essential for ongoing developments. Sherwat and Ebrashi [

15] elaborated on sustainability and scalability, creating a systematic social change. Russell et al. [

53] and Sudusinghe et al. [

54] researched the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework to drive change towards sustainability in the global supply chain.

Zimon et al. [

55] proposed guidance for managers and a three-phase approach, including practice identification, alignment with SDG goals, and implementation model.

Researchers intensively explored ways to achieve sustainability in the supply chain.

Chen and Kitsis [

37] developed the roadmap for a sustainable supply chain about antecedents of the sustainable supply chain, practices, and performance elements. They found that relational capabilities such as communication, collaboration, information sharing, and trust-building transform stakeholders’ pressure, moral motives, mindset, corporate vision, and management commitment to a sustainable outcome. Furthermore, they found media to be a powerful sustainability driver because the threat of media attention can force companies to act responsibly.

3. Methodology

The qualitative method was applied in this study to explore supply chain management strategies that leverage operational performance in the UN because a qualitative method enables identifying and understanding a phenomenon, a process, a perspective, a worldview, and the values of the people involved (see Creswell & Creswell, 2017). This study is grounded in an interpretivist philosophy, which focuses on understanding the subjective experiences and socially constructed realities that emerge within the context of humanitarian supply chain management. Given the complex and dynamic nature of the UN’s operations, this philosophical approach is particularly suited for exploring how individuals interpret and respond to these challenges. By utilizing an interpretivist framework, this study seeks to capture the diverse perspectives and lived experiences of supply chain managers, ensuring a richer, contextually informed analysis.

An inductive analysis was used in this study, employing a ‘bottom-up’ strategy where codes were developed directly from the data. Initially, open coding was applied, allowing key concepts and ideas to emerge naturally from the participants’ responses. These initial codes were then reviewed and refined, with similar codes being grouped together and more abstract themes identified. As the analysis progressed, recurring patterns across the interviews helped to shape and consolidate the themes, ensuring that the final coding structure was closely aligned with the research objectives. To ensure a thorough and reliable analysis of the interview data, the coding process was reviewed by a second and a third researcher. Any discrepancies between the initial and secondary coding were discussed and resolved through consensus. Thematic analysis was applied to identify recurring patterns and group them into broader themes relevant to the research objectives. The study reached thematic saturation, where no new themes or significant insights emerged after analyzing the final interviews. This point was determined when repeated themes and concepts consistently appeared across the data, and additional interviews no longer contributed new information relevant to the research objectives. At this stage, the data was considered to have fully captured the breadth of participants’ experiences and perspectives, ensuring that the analysis was both comprehensive and robust. This process allowed for a structured exploration of the strategies employed by UN supply chain managers, ensuring the findings were both comprehensive and aligned with the study’s aims.

We kept track of our analysis process through the notes. We also referred to secondary sources of documents that supported the themes and findings. These secondary data sources, such as internal UN reports and publicly available documentation on humanitarian operations, were used to verify and triangulate the insights gained from the interviews, ensuring that the study’s findings were well-supported by both primary and secondary evidence.

Next, the qualitative methodology can contribute to a more profound understanding of the rich text and thick descriptions with enhanced awareness of cultural differences to capture vast emergent possibilities, making it suitable for addressing the purpose of the study [

56]. This qualitative methodology used semi-structured, open-ended questions to interview a small sample of participants based on their experience and knowledge to help the researchers to address the research question [

57].

In this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine supply chain managers from the United Nations, chosen based on their direct successful contributions in various humanitarian missions across different geographical regions. Although the sample size of nine participants is relatively small, it is appropriate for the qualitative, exploratory nature of this study, which seeks to generate in-depth, context-specific insights. The focus on rich, detailed data allows for a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences and the operational environments in which they work, making this approach suitable for the research objectives. The semi-structured interview format was chosen to offer the necessary flexibility for exploring key themes, such as analytical innovation, leadership strategies, and risk management. This approach enabled the interviewer to ask follow-up questions that arose naturally from the participants’ responses, facilitating the collection of rich and detailed data. The questions were developed to align closely with the research objectives while remaining open-ended, allowing participants to share their experiences and perspectives freely. This flexibility was essential in capturing the complexity of the environments in which UN supply chain managers operate, ensuring that the data collected was both relevant and comprehensive for addressing the research aims.

Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 min, with open-ended questions designed to explore the strategies these managers employ to enhance operational performance. The interviews focused on three primary themes: analytical innovation and knowledge management, leadership strategies, and risk management. The data collected were transcribed and analyzed using thematic coding, which enabled the identification of key patterns and insights relevant to the study’s research objectives. This approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of the managers’ experiences and the operational contexts in which they work, allowing for the development of actionable strategies aligned with the research aims.

In qualitative research, there are several research designs. The case study was selected in this research because it seeks to answer “what”, “how”, and “why” questions, exploring a phenomenon within the real-world context using multiple data sources in robust cross-case analysis [

58]. This is a multiple case study because, in addition to semi-structured interviews, other sources are included, such as interviews and review of documents.

A cross-case analysis was conducted to compare the strategies and experiences across the different UN humanitarian missions. This approach enabled the identification of recurring patterns as well as unique, context-specific strategies. By analyzing multiple cases, the study was able to draw broader conclusions about the dynamic capabilities employed by supply chain managers, while also highlighting how different operational contexts shaped the application of these strategies. This comparative analysis added depth to the findings, ensuring that the insights generated were grounded in a diverse range of real-world experiences.

Ethical considerations were integral to the research process. Before the interviews, participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives and provided their informed consent. Confidentiality was strictly maintained by anonymizing participants’ identities and removing any identifiable information from the transcripts. All data were securely stored with access limited to the research team. Furthermore, this study received approval from the UN ethics office, ensuring that all research procedures adhered to organizational ethical standards for studies involving human subjects.

4. Empirical Findings

The research revealed several strategies that supply chain managers of the UN use to ensure operational efficiencies. There were nine UN supply chain managers interviewed, and their answers resulted in forming several strategies grouped around three identified themes: (a) analytical, innovation, and knowledge management strategies; (b) effective supply chain management leadership strategies; and (c) risk management strategies.

Table 1 shows the summary of themes, strategies, and coding.

5. Discussion and Contributions

5.1. Supply Chain Analytics

Supply chain analytics ensures visibility and evidence-based decision-making through technology and data mining. Most of the interviewed UN supply chain managers highlighted the importance of big data and technology that enables data-based decision-making, thus in alignment with the literature and statement of Dubey et al. (2019), who posited that analytics are knowledge-based and that both managers and employees should value the big data and benefits they make for the organization. P7 stated that data provides valuable insights and allows data-driven decisions. Therefore, combining technology-enabled resources and data management leads to a competitive advantage. Big data analytics capability has immense potential. This potential is particularly critical in the context of humanitarian operations, where rapid data processing can directly influence the effectiveness of relief efforts. A senior supply chain officer in the UN claimed that digital systems give visibility and business intelligence, thus critical to monitoring and measuring performance. Similarly, viewing performance enables one to change directions on time to ensure improvement.

Business performance monitoring is not a choice in supply chain management but should be viewed as a requirement. In this light, P4 confirmed that auditors understand the benefits of big data and its ability to measure efficiencies. Agarwal et al. (2019) posited that a performance measurement system is required because it quantifies the resources donors must provide. Similarly, P2 and P7 claimed that investment in technology is paramount, as well as working closely with the private sector to make humanitarian operations more entrepreneurial. Furthermore, P7 confirmed findings from Shamout (2019), who said that technology supports big data analytics by acquiring, storing, and transforming large volumes and a variety of data at high velocity. Technology may come with risks, too. Supply chain managers should have a balanced approach to new technology (Kwak et al., 2018). Therefore, P3 explained how implementing a supply chain planning tool was a struggle, while P8 said technology must be easy to use, facilitating change management.

5.2. Sensing the Operational Environment

Sensing the operational environment allows effective planning, demand forecasting, and optimizing resources. Dynamic capability conceptual framework promulgates three processes. Teece et al. [

7] highlighted that managers should start by identifying opportunities or sensing the environment. Similarly, P6 stated that the first step of successful implementation is always a thorough assessment of the environment. P1 continued about the need to reflect on the political situation, economic, security, and geographical location, thus applying different approaches and strategies. Supply chain management is more than just logistics; it involves effective planning, demand forecasting, and resource optimization, all of which are essential for delivering products and services efficiently [

59].

5.3. Training

Training initiatives that focus on developing best practices, reengineering processes, encouraging innovation, and promoting knowledge sharing are key to delivering solutions and improving competitiveness in humanitarian supply chains. Innovation is grounded in DCT. For illustration, Kurtmollaiev [

9] explained that combining sensing and seizing capabilities within a dynamic conceptual framework highlights the importance of innovation enabling adaptive strategies as the environment changes. P8 confirmed the same by saying that innovation is associated with change management. However, P1 warned that some global humanitarian organizations are highly regulated, thus limiting innovative approaches.

Dynamic capabilities are innovation-based, and innovation is linked to knowledge sharing. Moreover, Sabahi and Parast [

50] argued that organizations with innovative cultures contribute to knowledge sharing. Similarly, P7 claimed that knowledge sharing is critical for initiating change management and moving things forward. P3 added that creating knowledge by understanding current events in the organization may prepare the organization for certain events potentially happening in the future.

The organization only sometimes realizes the potential of knowledge sharing through best practices. For example, Aslam et al. [

4] argued that despite the supply chain concept having well-defined best practices, they will not be recognized or implemented if the supply chain managers lack an entrepreneurial approach. This statement aligns with the view of P7, who claimed that in the past, “people were not sharing lessons learned”, thus “keep repeating past mistakes”. However, P7 continued that she started reaching out to colleagues from the commercial sector to obtain best practices”. Similarly, P2 expressed the importance of working together with the private sector in terms of innovation to realize better business methods. Although Teece [

8] explained how best practices contribute to process reconfiguration, P1 explained that limited acceptance of commercial practices is because of “the organizational uniqueness and the top-down approach”.

Participant 4 deep-dived into process analysis to determine the level of value-added and necessity for change. Process reengineering is linked to data analysis for change. Participant 8 highlighted the importance of analyzing processes and stated. We were able to see the gaps. We were able to see the areas for improvement.

5.4. Effective Leadership

Effective leadership fosters a culture of accountability, change management, and integration through long-term partnerships, collaborations, and clear policies. Accountability is a critical factor for successful supply chain management. All participants confirmed that transparency and accountability are essential and high priorities. While participants acknowledged the importance of accountability as a key success factor and praised improvements made through technology and teamwork, some expressed concerns about areas for further improvement. Particularly, these participants highlighted differences when comparing practices in the private sector.

For example, Participant 3 criticized the level of accountability and compared it with the private sector, claiming the difference was significant. Supply chain managers should cultivate a culture of change management to ensure improvement. Reconfiguring a group of capabilities within DCT calls for adopting new practices, implying change management [

60]. Almost every participant emphasized the power of change management and interconnected it with other capabilities. Such leaders in high acceptance of new technologies were called entrepreneurial or innovative leaders by Aslam et al. [

4]. Standardization through well-defined policies is essential for global organizations. Friday et al. [

41] explained that standardization of procedures may serve as a risk mitigator, thus in alignment with contrasting institutional conceptual frameworks. For example, Flynn and Walker [

61], and Ordonez-Ponce and Khare [

62] elaborated on the pressure that multinational humanitarian organizational strategies endure to comply with internal and external regulations. However, Dubey et al. [

63] warned of the trade-off between adaptation and standardization to achieve anticipated responsiveness. For example, too many standardizations in procedures and formalities may result in inflexible supply chains [

64]. The rigidness of our rules and regulations often becomes an obstacle to more efficient and effective support. Collaboration appeared as very intensively discussed code during the interviews. According to Wilson et al. [

13], a supply chain based on collaboration results in coordinated humanitarian supply chain management. All participants emphasized the importance of “close collaboration”. Participant 1 highlighted that “collaboration and early involvement allows you to plan properly” and understand the customer’s needs. Similarly, Participant 8 said that collaborations allowed them to close identified gaps and bottlenecks promptly. Participants 1, 4, and 8 presented the example of Integrated Business Performance (IBP) meetings, the communication tool enabling business partners to collaborate. Aulkemeier et al. [

65], Prasanna and Haavisto [

11], and Parast [

21] explained that collaboration supported by IT systems or digital networks allows collaboration to become more efficient. Therefore, managers should be bold in investing in adequate IT capabilities as a long-term approach to enabling collaboration. Collaborations are more challenging to establish. They come with numerous impediments [

66]. In this regard, Adem et al. [

46] mentioned some governmental policies and socioeconomic settings. Chen and Kitsis [

37] and Kwak et al. [

19] extended to supply uncertainty, hostility, time pressure, changing priorities, and different understandings. Therefore, these impediments aligned with a statement by Participant 2, who claimed the UN system is very bureaucratic. Similarly, Participant 2 added, “We need to work together as a joint team to implement the solution. You can work together as a collaborative team without compromising your integrity or the process”.

5.5. Leading with Vision

Leading with vision sets priorities, leads projects effectively, and ensures their full implementation brings expected benefits and improvement. Managers lead the supply chains in different ways. Participant 3 elaborated on different types of leaders who championed their projects and said, “There [were] some good ones who supported” their initiatives and others who “were not very future visionary thinking”. Participant 2 elaborated on the leading supply chain within the SDG framework, that is, creating a positive “legacy” in the countries where the UN operates. In their research, Sudusinghe et al. [

54] called it driving change toward sustainability. Similarly, Participant 9 explained that he exercised change management by translating the SG vision of “well-managed, effective, and efficient client support in the mission”. The vision was frequently presented concerning training, efficiency, and policies. Therefore, Participant 8 said policies and frameworks help to remain aligned with “the aspiration and vision of the organization”. Project implementation could be an indicator of efficient leadership. Moreover, supply chain management in a humanitarian organization is under constant pressure to implement integrated structures, practices, and policies [

61]. During the interview, the majority of participants expressed their awareness of challenges related to implementation. Participant 8 said finding consensus among project stakeholders is a challenge. Shan et al. [

52] explained that the inability to implement collaborative innovation directly negatively impacts supply chain dynamic capability and sustainable supply chain performance. Conclusively, alignment between individual dynamic capabilities and the innovative or entrepreneurial leadership style leads to a sustainable supply chain. Project implementation under effective leadership relates to reconfiguration, the third stage of DCT [

8]. Reconfiguration usually includes several processes and activities seeking realignment. In this light, Participant 8 said, “Part of successful project management, you know, so you need to realign priorities. You need to readjust your priorities to stay on track”.

5.6. Managing by Understanding and Measuring the Entire End-to-End Supply Chain System

The UN supply chain managers are shifting from intuitional to data-driven leadership. Teece et al. [

7], in their DCT, highlighted the importance of reconfiguration that brings changes, hence improvement. However, there should be a way of measuring the level of improvement. Therefore, Agarwal et al. [

6] suggested a balanced scorecard for measuring the performance and the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) for evaluating the overall health of the UN supply chain management. Several participants expressed a deep understanding of the SCOR model. Participant 6 elaborated, “There is a system integration, process integration, and measures for managing capacity and workload. Having stable ERP is important”. Shamout [

24] detailed the processes of creating a measuring system that collects, mines, analyzes, and visualizes data, creating KPIs as performance indicators. Participant 2 confirmed that having systems that collect data and give visibility business intelligence over data is critical to monitoring and measuring your performance, seeing how you are doing, and enabling you to change direction if you need to change direction to improve the supply chain system. Managers with analytical capabilities are essential. They can absorb data quickly and make more effective data-driven decisions [

67]. Furthermore, such managers establish end-to-end supply chain systems to gain overall visibility. Gupta et al. [

68] confirmed that big data analytical potential depends on the managerial capacity to understand business needs and outputs extracted from big data. Mikalef et al. [

23] added that adapting analytical systems, especially big data, also depends on the organization’s maturity. In this light, most participants responded that it is necessary to introduce supply chain analytics in relief programs and manage the performance of every supply chain entity. Moreover, using ERP to manage the end-to-end supply chain also helps streamline supply chain operations in the UN.

5.7. Supply Chain Risk Management

The use of effective management mitigates disruptions and encounters resistance to change. Global humanitarian organizations are exposed to numerous disruptions in rapidly changing and unpredictable environments. Therefore, Teece et al. [

7], with their DCT, most adequately explained approaches to address these challenges. Participants 5 and 6 explained challenges with vendors’ performance and explained strategies. One of the risk management strategies they both touched on is establishing long-term partnerships because of expected benefits related to pricing, contract conditions, and improved understanding. Participant 3 explained the risk pertaining to lack of accountability. End-to-end supply chain measuring systems enhance visibility and effectively manage disruptions, thus resulting in sustainability, competitiveness, and resilience [

25]. As disruption potentially leads to financial losses, Participant 6 expressed concern by saying that all the costs are directly attributable to the supply chain and are not systematically measured. Similarly, Participant 4 voiced concern over the functionality of the ERP system that covers end-to-end supply chain processes and said that functionality is not developed the way it should be because of the ERP’s restrictions. Nevertheless, Fischer-Preßler et al. [

47] highlighted IT as the primary contributor to supply chain risk identification, resulting in identified risk factors. Resistance to change emerges as a risk factor. To introduce change, reconfiguration is required according to the dynamic capability conceptual framework [

7]. Participant 9 explained how the inability to manage resistance to change is already a risk. Participant 8 explained that there is always resistance when introducing a change. People are only sometimes ready to accept it.

5.8. Agile Strategies

Agile strategies enable an effective response to emergencies and uncertainties. The code agile emerged during the interview, thus showing an understanding of how the operational environment constantly changes and seeks agility. Aslam et al. [

4] explained that organizations must be able to embrace the risks, become agile, and constantly reconfigure their resources. Similarly, Participant 3 said that being agile and constantly adopting an ever-changing environment is essential. Participant 4 explained that he does not support a “one size fits all approach” because “each operational environment based on its particular “location, geographical, political, security” circumstances require adaptability. These managers demonstrated resilience by creating awareness of vulnerabilities [

24]. This approach aligns with the dynamic capability conceptual framework for sensing the environment before establishing an adequate strategy. Although our review of the literature emphasized innovation and technology as agility facilitators, thus risk mitigators, Kwak et al. [

19] argued that innovation can augment the risk because of numerous activities facilitated by IT. The latter has been echoed by Participant 7, who claimed that the ERP system that some humanitarian organizations embrace is not always the best. The system needs to be more responsive and agile. However, Participant 6 supported having the ERP system. Similarly, Participant 5 explained that the ERP system helped them to get visibility and, thus, act on time with changes. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) identified agility as their priority capability, especially relevant for goods transportation activities and rapid deployment of emergency teams [

69]. Shafiq and Soratana [

14] argued that supply chain managers should always have an emergency plan. This statement aligns with Participant 7, who said that procurement regulations cater to emergencies, thus allowing uncertainty to be addressed rapidly.

5.9. Sustainable Strategies

Sustainable strategies drive change toward sustainability and consider the environmental and social impacts. Half of the participants elaborated on the environmental impact of supply chain strategies in the UN. Some essential statements include the one from Participant 6, who said that supply chain strategy needs environmentally responsible actions and plans because environmental responsibility has been prioritized very highly. Participants 2 and 5 explained how important it is to onboard procurement officers with expertise in environmental engineering. Participant 6 continued that it is not just about retrieving, selling, transferring, and reusing materials but also completely overhauling and conducting environmental restoration, therefore in alignment with Creswell et al. [

55], who elaborated on environmental compliance, green production, and reverse logistics. The sustainable supply chain is increasingly gaining attention and is subject to external pressure from customers, suppliers, regulators, and investors [

19,

50].

The strategies identified in this study are influenced by several external factors, including donor constraints, geopolitical environments, and advancements in technology. Donor-imposed limitations, such as budget restrictions or specific compliance requirements, may reduce the flexibility of supply chain managers when applying certain strategies. Furthermore, the geopolitical context in which humanitarian operations take place often introduces complexities, including restricted access and security concerns, which can hinder the effectiveness of these approaches. While technological advancements provide opportunities to enhance supply chain efficiency, challenges may arise when the necessary infrastructure or technical expertise is lacking. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this research, and future studies could further investigate their impact on dynamic capabilities within humanitarian supply chains.

6. Practical Implications

This study offers valuable insights for enhancing supply chain management practices within the United Nations. First, the focus on analytical innovation and knowledge management demonstrates the importance of further integrating advanced data analytics and technology to support more efficient resource allocation, improve demand forecasting, and enhance decision-making processes. By continuing to implement these practices, UN supply chain managers can strengthen operational visibility and responsiveness, particularly in challenging and crisis-prone environments. Second, the findings highlight the need for continued emphasis on leadership development, fostering accountability, collaboration, and a culture of ongoing improvement. Leadership training initiatives can help ensure managers are well-prepared to navigate the complexities of humanitarian operations. Finally, the study underscores the importance of agile and sustainable risk management strategies, which are critical for maintaining resilience and adaptability in the face of disruptions. These strategies provide a framework for further strengthening the UN’s operational efficiency and effectiveness in delivering humanitarian aid.

7. Theoretical Implication

This study extends the application of dynamic capabilities theory to the context of humanitarian supply chains, contributing to the literature in multiple ways. While existing researches have predominantly focused on commercial supply chains, this study illustrates how dynamic capabilities, particularly analytical innovation, leadership, and risk management, can be effectively adapted to address the distinct challenges faced by humanitarian organizations such as the United Nations. By exploring how these capabilities are employed in volatile and resource-constrained environments, this research provides new insights into the role of dynamic capabilities in improving both operational efficiency and long-term sustainability in humanitarian settings. Furthermore, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how dynamic capabilities can be leveraged to enhance organizational resilience in complex environments, thereby enriching the theoretical foundations of dynamic capabilities in supply chain management.

8. Conclusions

The authors of this study present a pioneering exploration into the intersection of the United Nations and dynamic capability theory, providing valuable insights into the distinctive nature of the UN in contrast to conventional humanitarian organizations. Our research has illuminated a paradigm shift. Specifically, we found that the application of dynamic capabilities, typically associated with the commercial sector, resonates within the United Nations. Our study outlines the critical role of the UN in delivering its mandate in dynamic and disruptive environments. With a staggering 75% of supply chains experiencing disruptions [

57], the efficiency of UN supply chain managers becomes paramount. Our findings emphasize the need to adopt dynamic capabilities as a blueprint for other humanitarian organizations. Analytical capabilities prove essential in predicting and responding to natural disasters, as highlighted by Dubey et al. [

12]. Additionally, relational capabilities emerge as critical for fostering communication, collaboration, and trust-building among stakeholders, contributing to elevated performance and competitive advantage. The insights derived from this research may positively impact professional practice by educating leaders on strategies within the humanitarian supply chain. This is particularly relevant in vulnerable environments subject to strict scrutiny from Member States and donors. Moreover, the efficient implementation of dynamic capabilities, as concluded in our study, can contribute to the UN’s adherence to its 17 global sustainable development goals, fostering social well-being toward a more sustainable future for the world’s population. This research transfers the theoretical findings in humanitarian logistics, thus introducing a paradigm shift by demonstrating the applicability of dynamic capabilities within the UN (

Figure A1 in

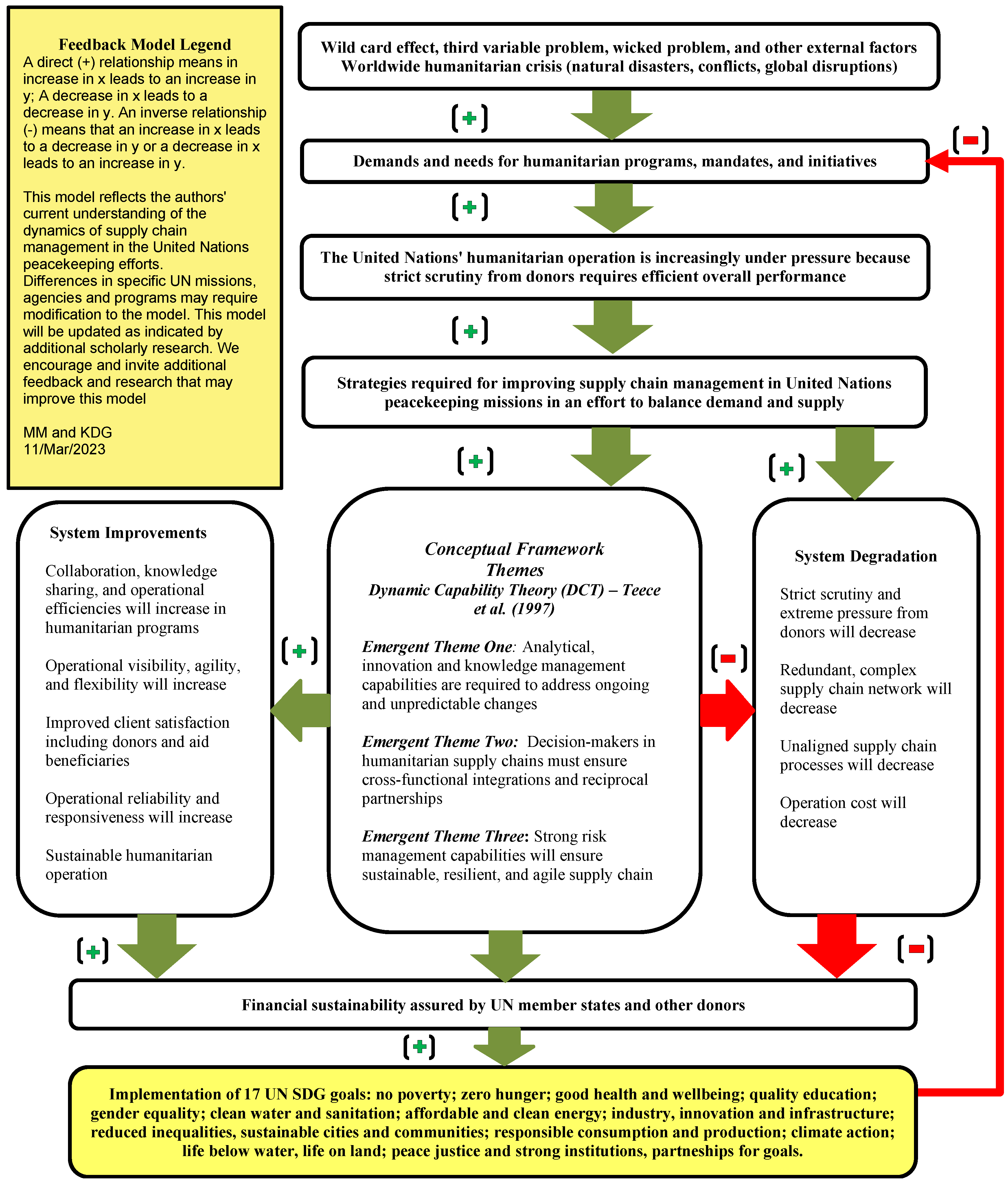

Appendix A).

9. Future Research Implications

Responses collected from the nine participants represent strategies supply chain managers use in UN peacekeeping missions. This study is the first research focusing on a specific humanitarian organization, the United Nations, that immensely impacts global humanitarian challenges.

While this study provides valuable insights into the strategies employed by UN supply chain managers, it is important to acknowledge the limitation of the relatively small sample size of nine participants. This sample size was appropriate for the qualitative, exploratory nature of this research, which aimed to gather in-depth perspectives from experienced managers in diverse humanitarian contexts. However, the findings should be interpreted with this limitation in mind, and caution should be exercised when generalizing these results. Additionally, the use of semi-structured interviews introduces the potential for interviewer bias, as the interpretation of responses could be influenced by the researcher’s perspective. Moreover, the study is context-specific, focusing on supply chain managers within the UN’s humanitarian missions, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other organizations or sectors. Future research could extend these findings by incorporating larger sample sizes or employing quantitative methods to validate and generalize the strategies identified. Additionally, employing quantitative methods would allow for the testing and validation of the strategies identified in this study, helping to generalize the findings. Future research could also explore the impact of external factors such as donor constraints, geopolitical environments, and technological advancements on the effectiveness of dynamic capability strategies within humanitarian supply chains. Since humanitarian supply chains are increasingly expected to deliver more assistance with limited resources, further insights into the supply chain cost-saving enablers are recommended to identify further saving potentials. Since the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has immense potential to create a more sustainable future, exploring which extended dynamic capabilities in the humanitarian supply chains contribute the most to achieving the SDG is recommended.