Checklist-Based Identification of Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Department Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Patients

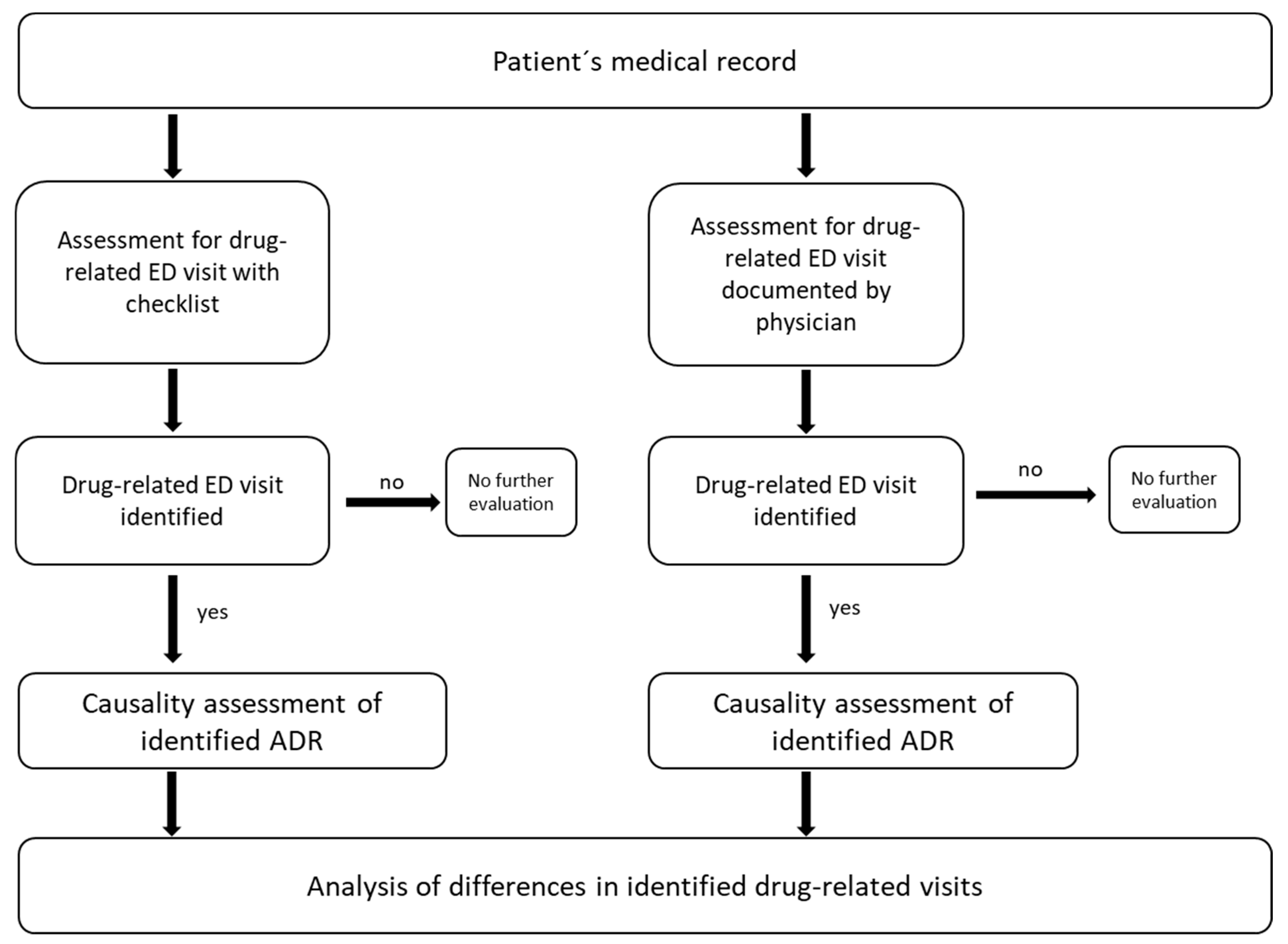

2.2. Study Protocol

2.3. Assessment for Drug-Related ED Visit with Checklist (CL-A)

2.4. Assessment for Drug-Related ED Visit Documented by Physicians (PD-A)

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR)

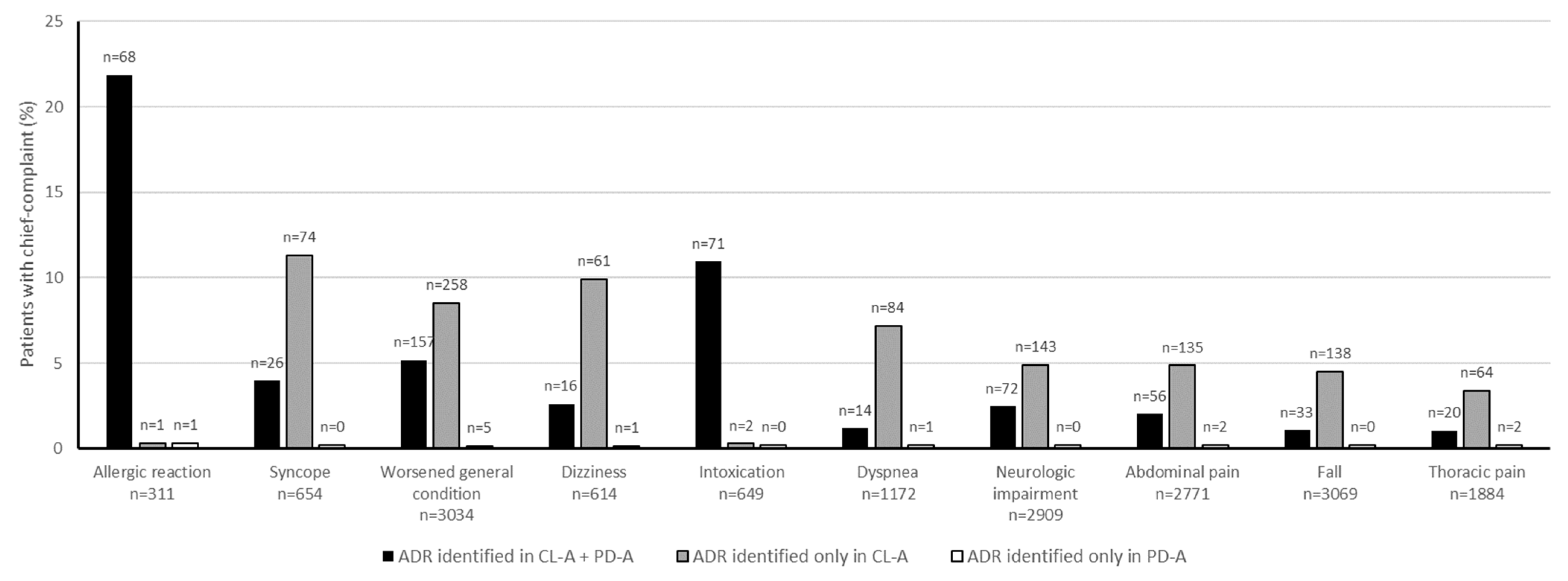

3.3. Chief Complaints

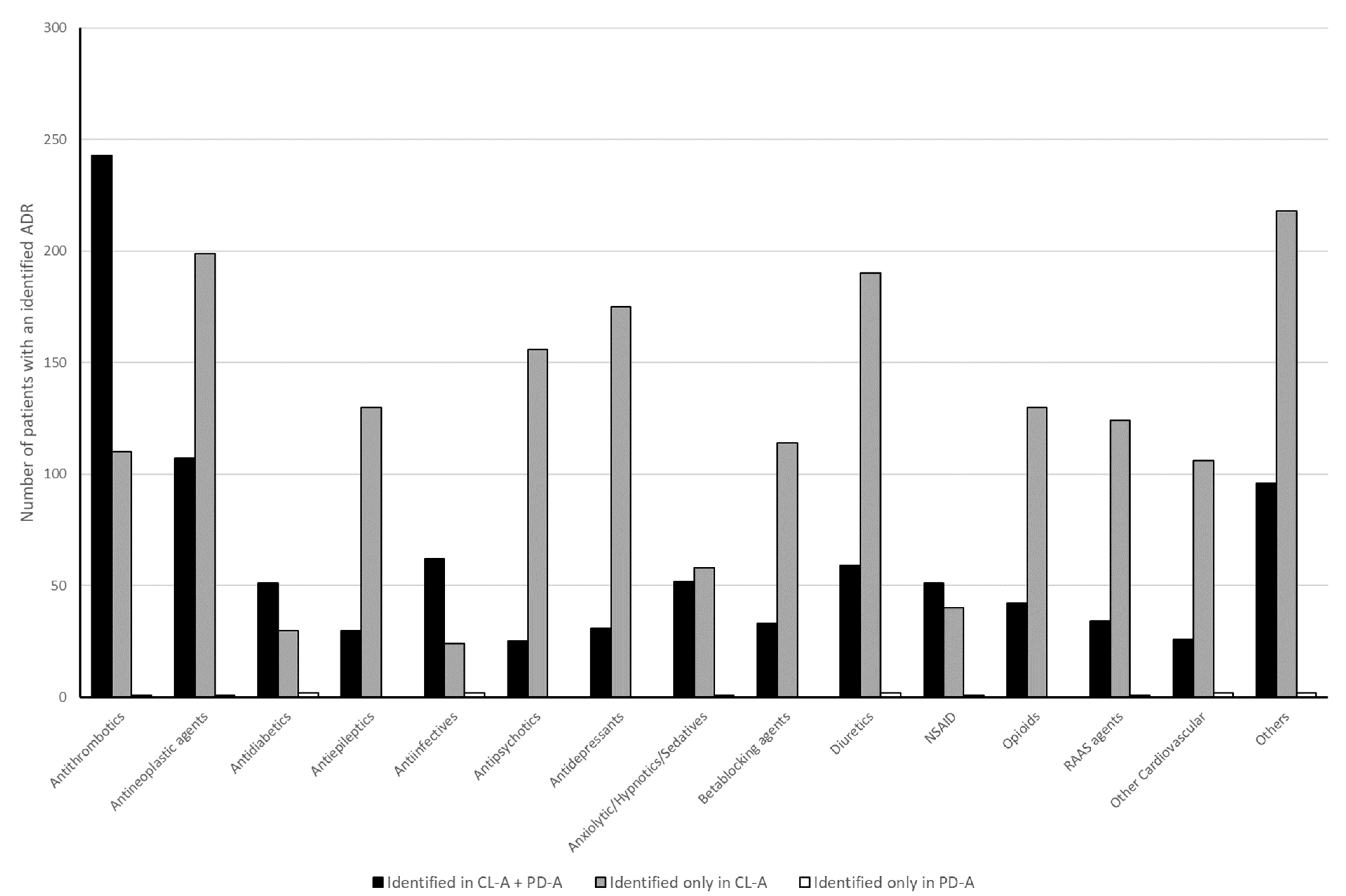

3.4. Drugs

4. Discussion

4.1. ADR Identification

4.2. Chief Complaints and Identified Drugs

4.3. Causality

4.4. Outlook

4.5. Summary

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADR | Adverse drug reaction |

| CL-A | Assessment of the medical record with checklist |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| OTC | over the counter |

| PD-A | Assessment of physician’s diagnosis in medical record |

| SmPC | Summary of product characteristics |

| UMC | Uppsala Monitoring Centre |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Fasipe, O.J.; Akhideno, P.E.; Owhin, O.S. The observed effect of adverse drug reactions on the length of hospital stay among medical inpatients in a Nigerian University Teaching Hospital. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2019, 3, 239784731985045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, A.I.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Shehab, N.; Hicks, L.A.; Sapiano, M.R.P.; Budnitz, D.S. National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Antibiotic Adverse Events Among Adults-United States, 2011-2015. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, A.; Dickens, J.; Jones, M.; Richmond, P.; Evans, R. Emergency department presentation following falls: Development of a routine falls surveillance system. Emerg. Med. J. 2011, 28, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, J.; Cutroneo, P.; Trifirò, G. Clinical and economic burden of adverse drug reactions. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4 (Suppl. S1), S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurig, A.M.; Böhme, M.; Just, K.S.; Scholl, C.; Dormann, H.; Plank-Kiegele, B.; Seufferlein, T.; Gräff, I.; Schwab, M.; Stingl, J.C. Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) and Emergencies. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2018, 115, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakkarainen, K.M.; Hedna, K.; Petzold, M.; Hägg, S. Percentage of patients with preventable adverse drug reactions and preventability of adverse drug reactions--a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.K.; Patel, P.B.; Bhalla, H.L.; Dwivedi, P.; Bajpai, V.; Kishore, S. Impact of suspected adverse drug reactions on mortality and length of hospital stay in the hospitalised patients: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komagamine, J.; Kobayashi, M. Prevalence of hospitalisation caused by adverse drug reactions at an internal medicine ward of a single centre in Japan: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, F.; Maas, R.; Sonst, A.; Patapovas, A.; Müller, F.; Plank-Kiegele, B.; Pfistermeister, B.; Schöffski, O.; Bürkle, T.; Dormann, H. Adverse drug events in patients admitted to an emergency department: An analysis of direct costs. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2015, 24, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirmohamed, M.; James, S.; Meakin, S.; Green, C.; Scott, A.K.; Walley, T.J.; Farrar, K.; Park, B.K.; Breckenridge, A.M. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: Prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ Open 2004, 2004, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.K.; Patel, P.B. Mortality among patients due to adverse drug reactions that lead to hospitalization: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 74, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazell, L.; Shakir, S.A. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, C.H.; Ruedinger, J.M.; Messmer, A.S.; Maile, S.; Peng, A.; Bodmer, M.; Kressig, R.W.; Kraehenbuehl, S.; Bingisser, R. Drug—Related emergency department visits by elderly patients presenting with non-specific complaints. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2013, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, H.; Criegee-Rieck, M.; Neubert, A.; Egger, T.; Geise, A.; Krebs, S.; Schneider, T.H.; Levy, M.; Hahn, E.G.; Brune, K. Lack of awareness of community-acquired adverse drug reactions upon hospital admission: Dimensions and consequences of a dilemma. Drug Saf. 2003, 26, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.S.; Gurwitz, J.H.; Avorn, J.; McCormick, D.; Jain, S.; Eckler, M.; Benser, M.; Bates, D.W. Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.S.; Lloyd, J.F.; Stoddard, G.J.; Nebeker, J.R.; Samore, M.H. Risk factors for adverse drug events: A 10-year analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005, 39, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawle, M.J.; Cooper, R.; Kuh, D.; Richards, M. Associations Between Polypharmacy and Cognitive and Physical Capability: A British Birth Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, C.M.; Zed, P.J.; Brubacher, J.R.; Abu-Laban, R.B.; Loewen, P.S.; Purssell, R.A. Do emergency physicians attribute drug-related emergency department visits to medication-related problems? Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 55, 493–502.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohl, C.M.; Robitaille, C.; Lord, V.; Dankoff, J.; Colacone, A.; Pham, L.; Bérard, A.; BPharm, J.P.; Afilalo, M. Emergency physician recognition of adverse drug-related events in elder patients presenting to an emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, S.; Spriet, I.; Indevuyst, C.; Vanbrabant, P.; Desruelles, D.; Sabbe, M.; Gillet, J.B.; Wilmer, A.; Willems, L. Pharmacist- versus physician-acquired medication history: A prospective study at the emergency department. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, R.J. Medication errors: The importance of an accurate drug history. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 67, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohl, C.M.; Badke, K.; Zhao, A.; Wickham, M.E.; Woo, S.A.; Sivilotti, M.L.A.; Perry, J.J. Prospective Validation of Clinical Criteria to Identify Emergency Department Patients at High Risk for Adverse Drug Events. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haerdtlein, A.; Boehmer, A.M.; Karsten Dafonte, K.; Rottenkolber, M.; Jaehde, U.; Dreischulte, T. Prioritisation of Adverse Drug Events Leading to Hospital Admission and Occurring during Hospitalisation: A RAND Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/international-conference-harmonisation-technical-requirements-registration-pharmaceuticals-human-use-topic-e-2-clinical-safety-data-management-definitions-and-standards-expedited-reporting-step_en.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Bates, D.W.; Miller, E.B.; Cullen, D.J.; Burdick, L.; Williams, L.; Laird, N.; Petersen, L.A.; Small, S.D.; Sweitzer, B.J.; ADE Prevention Study Group; et al. Patient risk factors for adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 2553–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsche, T.; Pfaff, J.; Schiller, P.; Kaltschmidt, J.; Pruszydlo, M.G.; Stremmel, W.; Walter-Sack, I.; Haefeli, W.E.; Encke, J. Prevention of adverse drug reactions in intensive care patients by personal intervention based on an electronic clinical decision support system. Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyboom, R.H.B.; Royer, R.J. Causality classification at pharmacovigilance centres in the european community. Pharmacoepidem. Drug Safe 1992, 1, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenkolber, D.; Schmiedl, S.; Rottenkolber, M.; Farker, K.; Saljé, K.; Mueller, S.; Hippius, M.; Thuermann, P.A.; Hasford, J. Adverse drug reactions in Germany: Direct costs of internal medicine hospitalizations. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011, 20, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemec, M.; Koller, M.T.; Nickel, C.H.; Maile, S.; Winterhalder, C.; Karrer, C.; Laifer, G.; Bingisser, R. Patients presenting to the emergency department with non-specific complaints: The Basel Non-specific Complaints (BANC) study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010, 17, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, R.; Roller, R.E.; Iglseder, B.; Dovjak, P.; Lechleitner, M.; Sommeregger, U.; Benvenuti-Falger, U.; Böhmdorfer, B.; Gosch, M. Komplikationen durch Diuretikatherapie bei geriatrischen Patienten. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2010, 160, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.R.; Van der Elst, M.; Hartholt, K.A. Drug-related falls in older patients: Implicated drugs, consequences, and possible prevention strategies. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2013, 4, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.; King, A.N.; Steadman, E. Impact of a Pharmacy-Led Fall Prevention Program for Institutionalized Older People. Sr. Care Pharm. 2021, 36, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Examination | Tool |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Medical history |

|

| #2 | Medication history (e.g., antithrombotics, diuretics, opioids, NSAIDs) |

|

| #3 | Relation of medication ↔ symptoms (e.g., bleeding, falls, syncope, skin rash) |

|

| #4 | Relation of medication ↔ laboratory finding (e.g., electrolytes, renal function, transaminases) |

|

| #5 | Relation of medication ↔ other pathologic findings (electrocardiogram, imaging) |

|

| #6 | Causality assessment (WHO UMC) |

|

| Overall ED Population (n = 34,747) | CL-A | PD-A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identified drug-related ED visits n (%) | 2071 (6.0) | 828 (2.4) | |

| Age-in-years median (IQR) | 50 (31–71) | 72 (56–81.25) | 69 (49–81) |

| Gender% (n) | |||

| Female | 40.0 (14,053) | 50.7 (1050) | 51.1 (423) |

| Male | 60.0 (20.694) | 49.3 (1021) | 48.9 (405) |

| Non-trauma% | 48.1 | 85.3 | 88.9 |

| Hospitalization rate% (n) | 36.5 (12,683) | 61.1 (1257) | 62.3 (516) |

| Top 10 chief complaints% (n) | |||

| Worsened general condition | 8.7 (3032) | 20.0 (415) | 19.4 (161) |

| Neurologic impairment | 8.4 (2909) | 10.4 (215) | 8.7 (72) |

| Fall | 8.8 (3069) | 8.3 (171) | 4.0 (33) |

| Abdominal pain | 8.0 (2771) | 6.9 (143) | 7.0 (58) |

| Syncope | 1.9 (654) | 4.8 (100) | 3.1 (26) |

| Dyspnea | 3.4 (1172) | 4.8 (98) | 1.8 (15) |

| Thoracic pain | 5.4 (1884) | 4.1 (84) | 2.7 (22) |

| Intoxication | 1.9 (649) | 3.5 (73) | 8.6 (71) |

| Allergic reaction | 0.9 (311) | 3.3 (69) | 8.3 (69) |

| Dizziness | 1.8 (614) | 3.2 (67) | 2.1 (17) |

| WHO causality assessment% (n) | |||

| Possible | 87.1 (1804) | 69.8 (578) | |

| Probable | 8.4 (174) | 19.0 (157) | |

| Certain | 4.5 (93) | 11.2 (93) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hellinger, B.J.; Bertsche, T.; Remane, Y.; Gries, A. Checklist-Based Identification of Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Department Patients. Medicines 2025, 12, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12040025

Hellinger BJ, Bertsche T, Remane Y, Gries A. Checklist-Based Identification of Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Department Patients. Medicines. 2025; 12(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellinger, Benjamin J., Thilo Bertsche, Yvonne Remane, and André Gries. 2025. "Checklist-Based Identification of Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Department Patients" Medicines 12, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12040025

APA StyleHellinger, B. J., Bertsche, T., Remane, Y., & Gries, A. (2025). Checklist-Based Identification of Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Department Patients. Medicines, 12(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12040025