Leveraging Household Food Waste Consumer Behaviour to Optimise Logistics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining Food Waste and Its Scope

2.2. Household Food Waste: Behavioural and Demographic Factors

2.3. Linking Food Waste to Logistics and Supply Chain Efficiency

2.4. Research Gap and Contribution

3. Materials and Methods

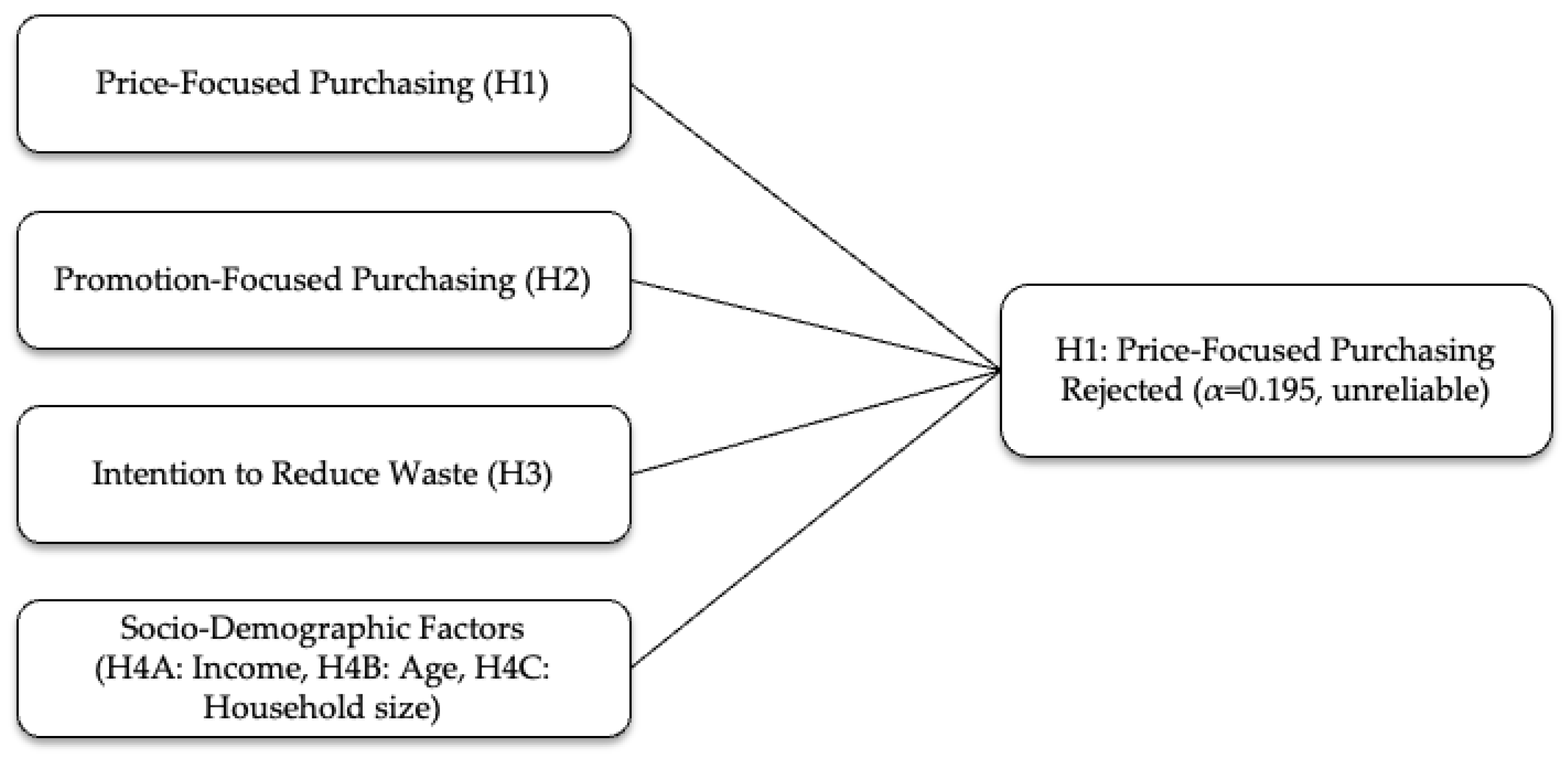

3.1. Hypotheses

3.2. Questionnaire Design

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Reliability

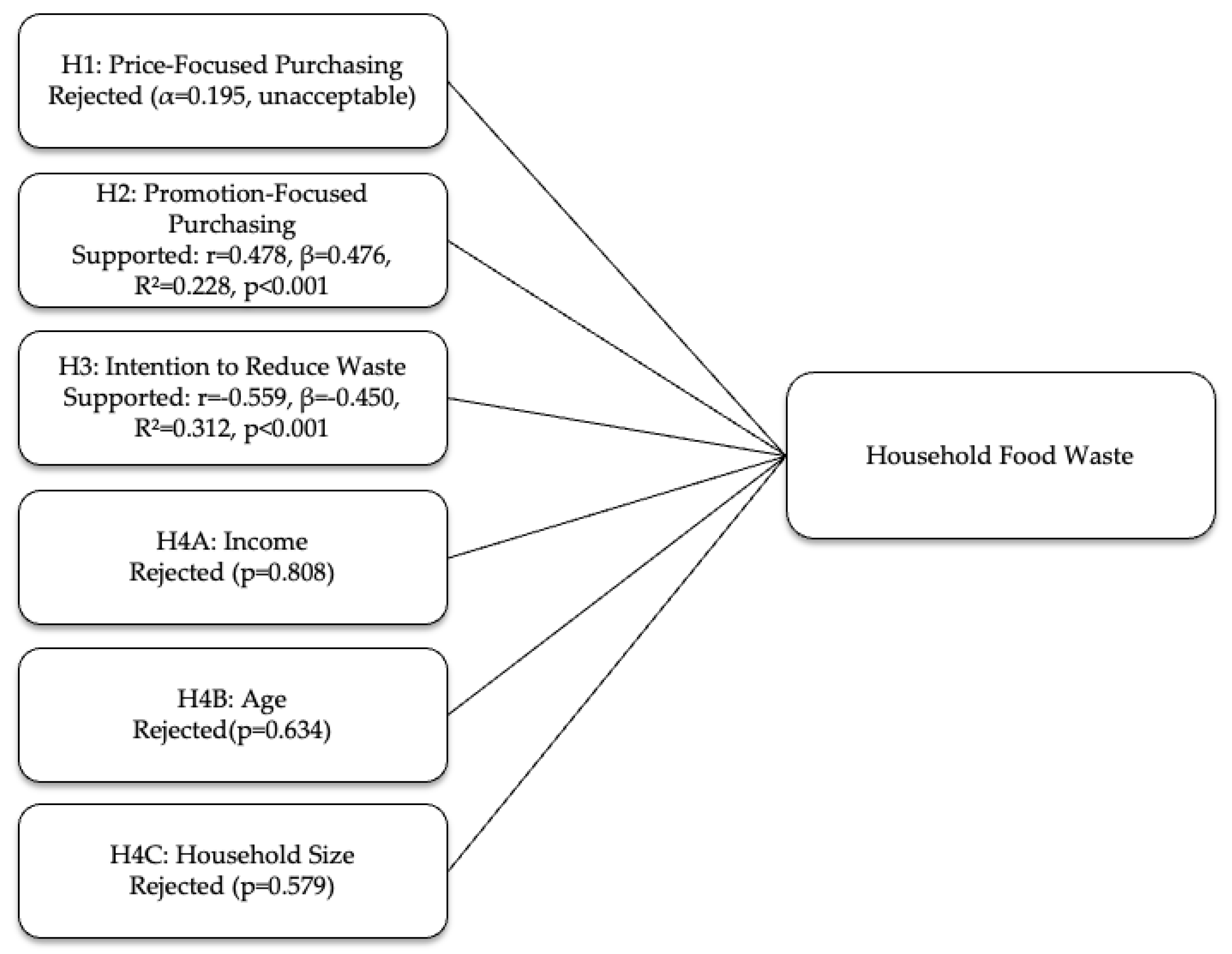

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Contributions

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ishangulyyev, R.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.H. Understanding Food Loss and Waste—Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food? Foods 2019, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention. In Proceedings of the International Congress Save Food! At Interpack2011, Düsseldorf, Germany, 16–17 May 2011; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. ISBN 978-92-5-107205-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.A.; Quested, T.E.; Lanctuit, H.; Zimmermann, D.; Espinoza-Orias, N.; Roulin, A. Nutrition in the Bin: A Nutritional and Environmental Assessment of Food Wasted in the UK. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109551-5.

- European Commission, Official Website—European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Giordano, C.; Franco, S. Household Food Waste from an International Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daszkiewicz, T. Food Production in the Context of Global Developmental Challenges. Agriculture 2022, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelodun, B.; Kim, S.H.; Odey, G.; Choi, K.-S. Assessment of Environmental and Economic Aspects of Household Food Waste Using a New Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) Index: A Case Study of Daegu, South Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrane, S.; Buonocore, E.; Capone, R.; Franzese, P.P. Exploring the Global Scientific Literature on Food Waste and Loss. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.T.; Papanikolaou, P.-A.; Katimertzoglou, P.; Ntalla, A.C.; Xenos, K.I. Household Food Waste in Greece: A Questionnaire Survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—ELSTAT. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/sdgs (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Albalate-Ramírez, A.; Padilla-Rivera, A.; Rueda-Avellaneda, J.F.; López-Hernández, B.N.; Cano-Gómez, J.J.; Rivas-García, P. Mapping the Sustainability of Waste-to-Energy Processes for Food Loss and Waste in Mexico—Part 1: Energy Feasibility Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahmani, E.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K. Demand Forecasting in Supply Chain Using Uni-Regression Deep Approximate Forecasting Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrank, J.; Hanchai, A.; Thongsalab, S.; Sawaddee, N.; Chanrattanagorn, K.; Ketkaew, C. Factors of Food Waste Reduction Underlying the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior: A Study of Consumer Behavior towards the Intention to Reduce Food Waste. Resources 2023, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; van Dam, Y.K. Consumer Driven Supply Chains: The Case of Dutch Organic Tomato. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2014, 2014, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, A.K.S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; Wout, T.; Wout, T.v.; Kamrava, M. A Consumer Behavioural Approach to Food Waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, N.V.; Lermen, F.H.; Echeveste, M.E.S. A Systematic Literature Review on Food Waste/Loss Prevention and Minimization Methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, X. Equilibrium Decisions for Multi-Firms Considering Consumer Quality Preference. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adana, S.; Manuj, I.; Herburger, M.; Cevikparmak, S.; Celik, H.; Uvet, H. Linking Decentralization in Decision-Making to Resilience Outcomes: A Supply Chain Orientation Perspective. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. Food Loss and Food Waste: Causes and Solutions by Michael Blakeney, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2019, Xi + 224 Pp. Dev. Econ. 2019, 57, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, S.; Faradilla, R.H.F.; Srzednicki, G.; Sundararajan, A. Fruit Wastes as a Flavoring Agent. In Adding Value to Fruit Wastes: Extraction, Properties, and Industrial Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 391–418. ISBN 978-044313842-3. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, E.S.C.; de Amorim, M.C.C.; Olszevski, N.; Silva, P.T.D.S.E. Composting of Winery Waste and Characteristics of the Final Compost According to Brazilian Legislation. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B Pestic. Food Contamin. Agric. Wastes 2021, 56, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitrón, G.; Martínez-Valdez, F.J.; Ojeda, F. Biogas Production from a Highly Organic Loaded Winery Effluent Through a Two-Stage Process. Bioenergy Res. 2019, 12, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Danish Habib, M.; Kaur, P.; Junaid Shahid Hasni, M.; Dhir, A. Drivers of Food Waste Reduction Behaviour in the Household Context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.-K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of Socio-Demographical, Behavioural and Attitudinal Factors on the Amount of Avoidable Food Waste Generated in Finnish Households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Jensen, J.H.; Jensen, M.H.; Kulikovskaja, V. Consumer Behaviour towards Price-Reduced Suboptimal Foods in the Supermarket and the Relation to Food Waste in Households. Appetite 2017, 116, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyam, A.; EI Barachi, M.; Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Shen, J.; Mathew, S.S. Enhancing Resilience and Reducing Waste in Food Supply Chains: A Systematic Review and Future Directions Leveraging Emerging Technologies. Int. J. Logist. Res. Applic. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, G.M.; Hendry, L.C.; Stevenson, M. Supply Chain Traceability: A Review of the Benefits and Its Relationship with Supply Chain Resilience. Prod. Plan. Control. 2023, 34, 1114–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, G.; Boutrup Jensen, B.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. The Relationship between Retail Price Promotions and Household-Level Food Waste: Busting the Myth with Behavioural Data? Waste Manag. 2024, 173, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; Apostolidou, I.; Michailidis, A. Food Traceability: A Consumer-Centric Supply Chain Approach on Sustainable Tomato. Foods 2021, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; Apostolidou, I.; Tsolakis, N. Challenges and Opportunities of Supply Chain Traceability: Insights from Emergent Agri-Food Sector. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2024, 30, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzembacher, D.E.; Vieira, L.M.; de Barcellos, M.D. An Analysis of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives to Reduce Food Loss and Waste in an Emerging Country—Brazil. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for Household Food Waste with Special Attention to Packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Nagalingam, S.; Gurd, B. A Resilience Model for Cold Chain Logistics of Perishable Products. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Vinaya Laxmi, K.; Gupta, N.K.; Wankhade, M.P.; Bapat, V. A Blockchain Security Based IoT-Enabled System for Safe and Effective Logistics Management in IR 4.0. Int. J. Intel. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, C.; Li, M.; Pei, Y. Customer Flow Spillovers in Retailers’ Short- and Long-Term Decisions: Profitability and Dynamic Mechanisms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2026, 88, 104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M. Fermatean Fuzzy Group Decision Model for Agile, Resilient and Sustainable Logistics Service Provider Selection in the Manufacturing Industry. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 20, 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritikou, T.; Panagiotakos, D.; Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K. Investigating the Determinants of Greek Households Food Waste Prevention Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding Food Waste by Romanian Consumers: The Importance of Planning and Shopping Routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Honhon, D. Don’t Waste That Free Lettuce! Impact of BOGOF Promotions on Retail Profit and Food Waste. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H.-J. Identifying Factors That Promote Consumer Behaviours Causing Expired Domestic Food Waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merian, S.; Stöeckli, S.; Fuchs, K.L.; Natter, M. Buy Three to Waste One? How Real-World Purchase Data Predict Groups of Food Wasters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.; Albers, S. Retailer Competition in Shopbots. SSRN J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, K.; Lambrechts, W.; van Osch, A.; Semeijn, J. How Consumer Behavior in Daily Food Provisioning Affects Food Waste at Household Level in The Netherlands. Foods 2019, 8, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Food Waste Prevention in Athens, Greece: The Effect of Family Characteristics. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Barrera, E.; Hertel, T. Global Food Waste across the Income Spectrum: Implications for Food Prices, Production and Resource Use. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghinea, C.; Ghiuta, O.-A. Household Food Waste Generation: Young Consumers Behaviour, Habits and Attitudes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 2185–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwood, S.; Byrne, N.; McCarthy, O.; Heavin, C.; Barlow, P. Examining the Relationship between Consumers’ Food-Related Actions, Wider Pro-Environmental Behaviours, and Food Waste Frequency: A Case Study of the More Conscious Consumer. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Costarelli, V.; Chroni, C. The Implications of Food Waste Generation on Climate Change: The Case of Greece. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Harknett, K. What’s to like? Facebook as a Tool for Survey Data Collection. Sociol. Methods Res. 2022, 51, 108–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Medín, A.F.; Losada-López, C. Can Marketing Help in Tackling Food Waste?: Proposals in Developed Countries. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, T.; Beckert, W.; Smith, R.; Cornelsen, L. The Impact of Price Promotions on Sales of Unhealthy Food and Drink Products in British Retail Stores. Health Econ 2023, 32, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigna, J.P.; Mainardes, E.W. Sales Promotion and the Purchasing Behavior of Food Consumers. Rev. Bras. Mark. 2019, 18, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–19 | <1 |

| 20–29 | 62 | |

| 30–39 | 19 | |

| 40–49 | 10 | |

| 50–59 | 7 | |

| 60–69 | <1 | |

| Gender | Male | 33 |

| Female | 67 | |

| Household size | 1 person | 14 |

| 2 persons | 36 | |

| 3 persons | 20 | |

| 4+ persons | 30 | |

| Annual Income (€) | ≤5947 | 18 |

| 5948–8752 | 21 | |

| 8753–12,308 | 30 | |

| >12,308 | 31 |

| Variable | No of Items Included | Coefficient of Cronbach’s Alpha | Reliability Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household food waste generation | 4 | 0.857 | Good |

| Price-focused purchasing | 4 | 0.195 | Unacceptable |

| Promotion-focused purchasing | 4 | 0.868 | Good |

| Intention to reduce food waste | 5 | 0.882 | Good |

| Hypothesis | Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Pearson’s r | R2 | β Coefficient | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Household food waste | Promotion-focused purchasing | 0.478 | 0.228 | 0.476 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | Intention to reduce food waste | −0.559 | 0.312 | −0.450 | <0.001 | Supported | |

| H4A | Income | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.202 | 0.808 | Rejected | |

| H4B | Age | 0.036 | 0.001 | −0.179 | 0.634 | Rejected | |

| H4C | Household Size | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.142 | 0.579 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntai, S.; Kontopanou, M.; Anastasiadis, F. Leveraging Household Food Waste Consumer Behaviour to Optimise Logistics. Logistics 2025, 9, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030126

Ntai S, Kontopanou M, Anastasiadis F. Leveraging Household Food Waste Consumer Behaviour to Optimise Logistics. Logistics. 2025; 9(3):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030126

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtai, Sotiris, Maria Kontopanou, and Foivos Anastasiadis. 2025. "Leveraging Household Food Waste Consumer Behaviour to Optimise Logistics" Logistics 9, no. 3: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030126

APA StyleNtai, S., Kontopanou, M., & Anastasiadis, F. (2025). Leveraging Household Food Waste Consumer Behaviour to Optimise Logistics. Logistics, 9(3), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030126