Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Disruption: The Focus on Cross-Border Suppliers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. SCRES

2.2. Existing SCRES Assessments

3. Development of the Proposed Tool

3.1. The LPI as a Reference Tool

3.2. Development of the Proposed Tool: Questionnaire Assessment

3.3. Validation of the Proposed Tool

4. Case Study Validation

4.1. The Case Study Context: Thai Construction Material Cross-Border Suppliers Along Thai–Laos Border

4.2. Results and Discussions

4.3. Reflections on the Proposed Tool

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Q. Analysis of cross-border supply chain network system. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electromechanical Control Technology and Transportation (ICECTT), Nanchang, China, 15–17 May 2020; pp. 603–606. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, F.; You, J.X. Striking a balance between supply chain resilience and supply chain vulnerability in the cross-border e-commerce supply chain. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 320–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, F. Matching governance mechanisms with transaction-specific investment types and supplier roles: An empirical study of cross-border outsourcing relationships. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneci. COVID-19: Its Impact on the Automotive Supply Chain and Lessons Learned. 2021. Available online: https://www.sneci.com/blog/covid-19-its-impact-on-the-automotive-supply-chain-and-lessons-learned/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Karwasra, K.; Soni, G.; Mangla, S.K.; Kazancoglu, Y. Assessing dairy supply chain vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 27, 2378–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zighan, S. Managing the great bullwhip effects caused by COVID-19. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2021, 15, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbuch, Y. Suez Canal Ship Crisis May Unleash Worldwide Toilet Paper Shortage, New York Post. 2021. Available online: https://nypost.com/2021/03/26/suez-canal-crisis-may-unleash-worldwide-toilet-paper-shortage/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Maskrey, A.; Jain, G.; Lavell, A. The social construction of systemic risk: Towards an actionable framework for risk governance. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2023, 32, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wiengarten, F.; Choi, T.Y. Supplier-supplier coopetition and supply chain disruption: First-tier supplier resilience in the tetradic context. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adobor, H.; McMullen, R.S. Supply chain resilience: A dynamic and multidimensional approach. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 1451–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Quaddus, M. Supply chain readiness, response and recovery for resilience. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Seth, N.; Agarwal, A. Evaluation of supply chain resilience index: A graph theory-based approach. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 735–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; da Silva, A.L.; Tate, W.L.; Christopher, M. Purchasing and supply management (PSM) contribution to supply-side resilience. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivajee, V.; Singh, R.K.; Rastogi, S. Procurement system for resilient supply chain amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic literature review. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2023, 16, 397–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, A.K.; Patrucco, A.S. Guest editorial: A purchasing and supply management view of supply resilience for better crisis response. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2022, 28, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chong, W.K.; Li, D. A systematic literature review of the capabilities and performance metrics of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4541–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookbanks, M.; Parry, G.C. The impact of Industry 4.0 technologies on the resilience of established cross-border supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 29, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Kumar, S.; Soni, U.; Chandra, C. Supply chain resilience: Model development and empirical analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 6779–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmer, J.; Bugert, N.; Lasch, R. Analysis of resilience strategies and ripple effect in blockchain-coordinated supply chains: An agent-based simulation study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, K.; Stevenson, M.; van Donk, D.P. Dealing with the unpredictable: Supply chain resilience. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Croxton, K.L.; Fiksel, J. Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development and implementation of an assessment tool. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.S.; Rasi, R.Z.R.M.; Ahmad, M.F.B.; Rehman, F. What is supply chain risk management? A review. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 9233–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, H.L.; Banomyong, R.; Varadejsatitwong, P.; Julagasigorn, P. Mitigating risks in the disaster management cycle. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7454760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, R.; Schoenherr, T. Assessing and managing risks using the supply chain risk management process (SCRMP). Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2011, 16, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.; Koronis, E. Supply chain resilience: Definition of concept and its formative elements. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukamuhabwa, B.R.; Stevenson, M.; Busby, J.; Zorzini, M. Supply chain resilience: Definition, review and theoretical foundations for Further Study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5592–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Peck, H. Building the Resilient Supply Chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarian, M.; Parast, M.M. An integrative approach to supply chain disruption risk and resilience management: A literature review. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 24, 427–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Holweg, M. Supply chain 2.0: Managing supply chains in the era of turbulence. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusiri, N.; Banomyong, R.; Julagasigorn, P.; Varadejsatitwong, V.; Dhami, N. A purchasing portfolio model for humanitarian supply chain resilience: Perspectives from a development aid context. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 11, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljic, P. Purchasing must become supply management. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1983, 61, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Roath, A.S.; Daugherty, P.J.; Genchev, S.E.; Chen, H.; Arndt, A.D.; Richey, R.G. Supply chain collaboration: What’s happening? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2005, 16, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sohal, A.S.; Prajogo, D.L. Supply chain operational risk mitigation: A collaborative approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 2186–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Two views of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 62, 4031–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mahfouz, A.; Arisha, A. Analysing supply chain resilience: Integrating the constructs in a concept mapping framework via a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y.; Rice, J.B., Jr. A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson, E.; Lapidoth, L.D.M. Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Supply Chain Risks: A Case Study of the Inbound Logistics at Volvo CE. Master’s Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, T.J.; Fiksel, J.; Croxton, K.L. Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development of a conceptual framework. J. Bus. Logist. 2010, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Lopez, C.; Zubairu, N.; Chen, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Modelling enablers for building agri-food supply chain resilience: Insights from a comparative analysis of Argentina and France. Prod. Plan. Control 2024, 35, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language testing and assessment research: A literature review. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, M.; Govindan, K.; Maihami, R. Stochastic optimization of disruption-driven supply chain network design with a new resilience metric. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 230, 107755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegler, V.L.; Naim, M.M.; Wikner, J. A control engineering approach to the assessment of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 6162–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.; Verma, P.; Tiwari, M.K. Assessment of pre and post-disaster supply chain resilience based on network structural parameters with CVaR as a risk measure. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhotiya, G.K.; Soni, G.; Jain, V.; Joshi, R.; Mittal, S. Assessing supply chain resilience to the outbreak of COVID-19 in Indian manufacturing firms. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 1161–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguila, J.O.; ElMaraghy, W. Supply chain resilience and structure: An evaluation framework. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 28, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Modelling enablers of supply chain risk mitigation in electronic supply chains: A Grey-DEMATEL approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 87, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvis, J.; Ojala, L.; Shepherd, B.; Ulybina, D.; Wiederer, C. Connecting to Compete 2023: Trade Logistics in an Uncertain Global Economy—The Logistics Performance Index and Its Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beysenbaev, R.; Dus, Y. Proposals for improving the Logistics Performance Index. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2020, 35, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongur, U.; Turkcan, K.; Ekmen-Ozcelik, S. Logistics performance and export variety: Evidence from Turkey. Cent. Bank Rev. 2020, 20, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.A.; Appolloni, A.; Shaikh, A.R. Does the stakeholder’s relationship affect supply chain resilience and organizational performance? Empirical evidence from the supply chain community of Pakistan. Int. J. Emerg. Markets 2024, 19, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.F.; Ellram, L.M. A portfolio approach to supplier relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Dong, Z.S.; Lev, B. Supplier selection in disaster operations management: Review and research gap identification. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; Christopher, M.; Da Silva, A.L. Achieving supply chain resilience: The role of procurement. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.S.; Wagner, S.M.; Aggarwal, V. Positioning of commodities using the Kraljic portfolio matrix. J. Purch. Supply. Manag. 2012, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamphayphan, T.; Toyoda, T.; Czerkawski, C.; Kyophilavong, P. Export supply of electricity from Laos to Thailand: An econometric analysis. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2015, 5, 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Asa, S.P. The Impact of Trade Cost and Trade Facilitation on Export of Lao PDR; Mekong Institute: Khon Kaen, Thailand, 2014; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- OEC. Historical Data. Thailand/Laos: Historical Data. 2024. Available online: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/tha/partner/lao/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Kyophilavong, P.; Lamphayphan, T. Lao PDR Country Report. In Financing ASEAN Connectivity; Zen, F., Regan, M., Eds.; ERIA Research Project Report FY2013, No. 15; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 131–165. [Google Scholar]

| Categories of Supply Chain Resilience Capability | Examples of Key Enablers | Examples of Implementable Initiatives and Mitigating Policies in Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Supply chain flexibility [10,26,28] |

| |

| Supply chain redundancy [26,28] |

| |

| Supply chain collaboration [26,28] |

| |

| Supply chain agility [26,28] |

| Indicator: Flexibility and Redundancy Resilience Capabilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Assessment components in perspective of the inbound supply chain of the supplier tier-1 | Sub-indicators | Assessment components in perspective of the outbound supply chain of the supplier tier-1 |

| (1) An ability to have (or apply) an appropriate purchasing portfolio and supplier categorization [30,31] (2) An ability to have an expansion and diversification of locations/sources of supply [26] (3) An ability to have a strengthened partnership with its strategic supplier and request to have a safety stock of important commodities to ensure smooth supply [20] (4) An ability to have a strengthened partnership with its strategic supplier and request increased supplies on short notice [50] | Flexible supply | (1) An ability to assist (or provide information or participate) buyer in analyzing and categorizing purchasing portfolio and supplier [30,31] (2) An ability to provide expansion of locations of supply by having inventories in multiple locations domestically and internationally [26] (3) An ability to provide a strengthened partnership and store safety stocks or extra inventories (i.e., important commodities) for buyers [20] (4) an ability to provide a strengthened partnership and increased supplies to be delivered at short notice (i.e., having spare/slack capacity) [50] |

| (1) An ability to have a diversification of inbound distribution channels (and transport modes) [26] (2) An ability to redeploy and expand its own transport resources for inbound deliveries (in case the supplier tier-1 uses its own transport resources) [26] (3) An ability to have an expansion/diversification of transport outsourcing options [26] | Flexible transport and distribution channel | (1) An ability to provide a diversification of outbound distribution channels (and transport modes) [26] (2) An ability to redeploy and expand its own transport resources for outbound deliveries (in case the supplier tier-1 uses its own transport resources for deliveries to the buyer) [26] (3) An ability to provide an expansion/diversification of transport outsourcing options [26] |

| (1) An ability to have a strengthened partnership with its strategic supplier and request to build capacities of the workforce to be more productive and multi-skilled. Also, an ability to build capacities of its own workforce to handle inbound deliveries [26] (2) An ability to have a strengthened partnership with its strategic supplier and request to redeploy and expand the workforce. Also, an ability to redeploy and expand its workforce to handle inbound deliveries [26] | Flexible workforce arrangement | (1) An ability to provide a strengthened partnership and prepare to build the capacities of its workforce (to handle outbound deliveries) to be more productive and multi-skilled [26] (2) An ability to provide a strengthened partnership and prepare to redeploy and expand its workforce (to handle outbound deliveries) [26] |

| Indicator: Collaboration and Agility Resilience Capabilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Assessment components in perspective of the inbound supply chain of the supplier tier-1 | Sub-indicators | Assessment components in perspective of the outbound supply chain of the supplier tier-1 |

| (1) An ability to have information and supply chain performances exchanged, shared, received, tracked, and monitored by other suppliers [28] (2) An ability to analyze and evaluate the performance of supply (from other suppliers) [28] | Supply chain visibility | (1) An ability to share and exchange its information for the buyers to track and monitor the performances and receive useful information from the buyer [28] (2) An ability to analyze and forecast demands from the buyer [28] |

| (1) An ability to prioritize its suppliers (2) An ability to have an appropriate establishment of different levels of relationships with other suppliers [30] | Relationship orientation | (1) An ability to assist the buyer in prioritizing the supply base (2) An ability to assist the buyer in establishing appropriate relationships [30] |

| (1) An ability to have proactive, regular, and responsive communicate with other suppliers. Also, it includes the ability to have an alignment of communication channels [28] | Supply chain communication | (1) An ability to provide proactive, regular, and responsive communication with the buyer. Also, it includes an ability to provide an alignment of communication channels [28] |

| Sub-Indicator (and Its Assessment Component #) | Question |

|---|---|

| Flexible supply (the 1st assessment component under the inbound supply chain perspective) | Do you know who your strategic suppliers are or what your strategic purchased items are? Have you prioritized your suppliers and purchased items? |

| Do you regularly prioritize (or have you prioritized) your suppliers by considering other characteristics/criteria of your suppliers other than the highest volume purchases or the highest spending per year? | |

| Do you involve risks, difficulties, and challenges of acquiring and procuring items as criteria when you prioritize or differentiate between strategic suppliers (strategic items) and others? | |

| Do you know (or have you applied) the concept of the Kraljic model (or something similar) when differentiating between strategic suppliers (strategic items) and others (i.e., it can result in four categories: non-critical, leverage, bottleneck, and strategic. All categories will have different partnership engagements and sourcing strategies.)? | |

| The answers range across five levels: Not at all, Rarely/Somewhat agree, Sometimes/Agree, Often/Strongly agree, and Nearly always/Totally agree. | |

| Name | Business Size | Types of Cross-Border Business and Customer in Laos | Types of Transportation Used for Cross-Border Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, B, C | Big (with market capitalization of ≥THB 1000 million) |

|

|

| D, E | Small (with market capitalization of <THB 100 million) |

|

|

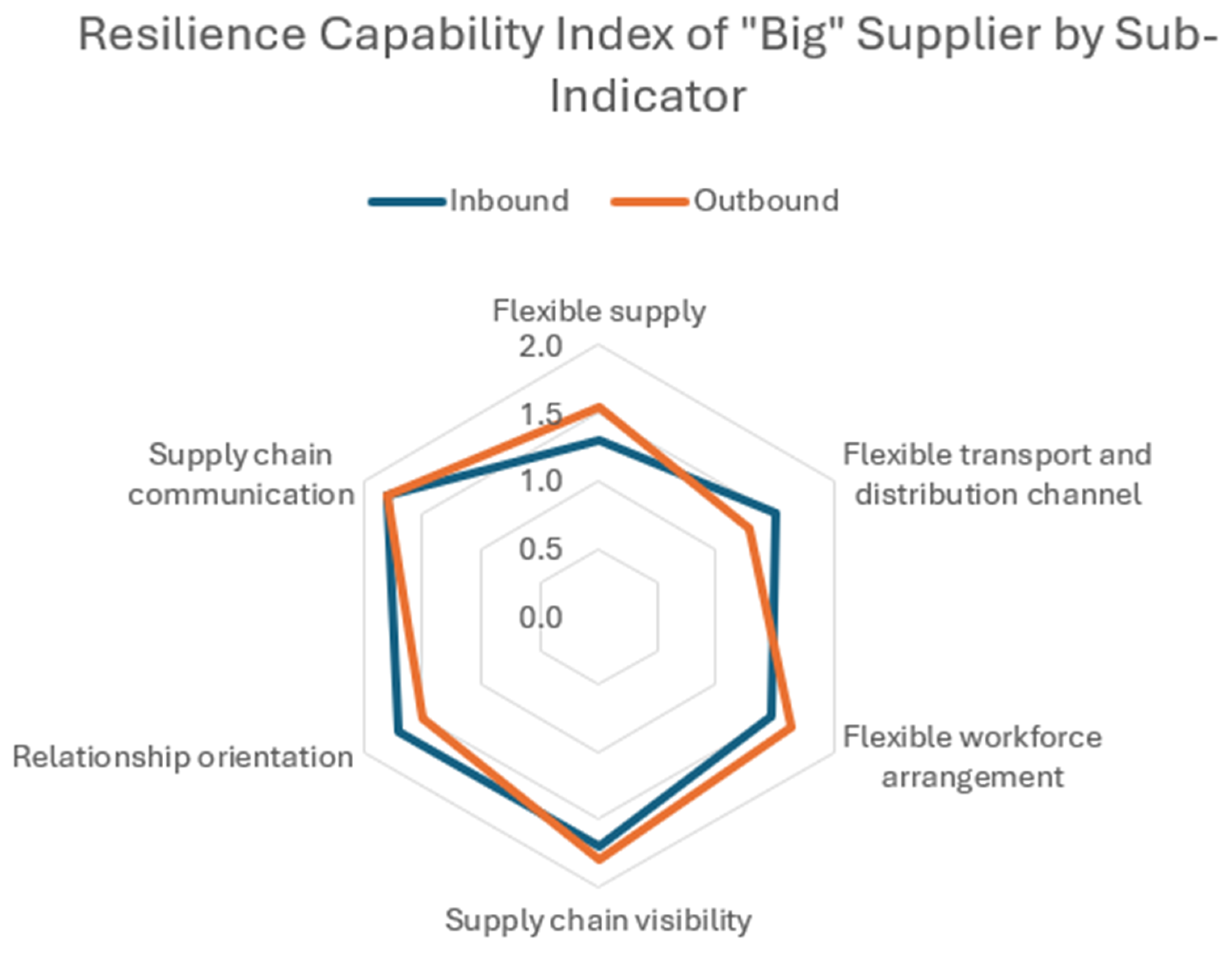

| Indicator | Sub-Indicator | Assessment Component # | Resilient Index (Inbound Supply Chain Perspective) | Resilient Index (Outbound Supply Chain Perspective) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The integrated supply chain flexibility and redundancy resilience capabilities | Flexible supply | #1 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| #2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | ||

| #3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | ||

| #4 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||

| Flexible transport and distribution channel | #1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| #2 | 1.6 | 1.4 | ||

| #3 | 1.5 | 0.9 | ||

| Flexible workforce arrangement | #1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | |

| #2 | 1.5 | 1.8 | ||

| The integrated supply chain collaboration and agility resilience capabilities | Supply chain visibility | #1 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| #2 | 1.6 | 1.8 | ||

| Relationship orientation | #1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | |

| #2 | 1.6 | 1.5 | ||

| Supply chain communication | #1 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Indicator | Sub-Indicator | Assessment Component # | Resilient Index (Inbound Supply Chain Perspective) | Resilient Index (Outbound Supply Chain Perspective) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The integrated supply chain flexibility and redundancy resilience capabilities | Flexible supply | #1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| #2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| #3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| #4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Flexible transport and distribution channel | #1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| #2 | 0.3 | 1.0 | ||

| #3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Flexible workforce arrangement | #1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| #2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| The integrated supply chain collaboration and agility resilience capabilities | Supply chain visibility | #1 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| #2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | ||

| Relationship orientation | #1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | |

| #2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Supply chain communication | #1 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Table | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Models [41,42] | Robust optimization under uncertainty; quantitative insights; customizability | High computational demand; data-intensive; complex implementation |

| Simulation Techniques [43] | Dynamic scenario analysis; risk quantification (CVaR); visualization | Time/resource-intensive; limited generalizability; expertise required |

| Graph Theoretical Approach [12] | Simplicity; network visualization; broad applicability | Static nature; simplistic assumptions; limited predictive capabilities |

| Bayesian/Analytical Models [44,45] | Uncertainty modeling; causal relationships; flexibility | Computationally intensive; data-dependent; interpretation challenges |

| Cross-Border Resilience Performance Index (proposed by the authors) | Practical; user-friendly; qualitative and quantitative integration; benchmarking capability | Limited depth in quantitative modeling; potential subjectivity; focused on cross-border scenarios |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banomyong, R.; Bhusiri, N.; Julagasigorn, P.; Varadejsatitwong, P. Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Disruption: The Focus on Cross-Border Suppliers. Logistics 2025, 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010001

Banomyong R, Bhusiri N, Julagasigorn P, Varadejsatitwong P. Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Disruption: The Focus on Cross-Border Suppliers. Logistics. 2025; 9(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanomyong, Ruth, Narath Bhusiri, Puthipong Julagasigorn, and Paitoon Varadejsatitwong. 2025. "Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Disruption: The Focus on Cross-Border Suppliers" Logistics 9, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010001

APA StyleBanomyong, R., Bhusiri, N., Julagasigorn, P., & Varadejsatitwong, P. (2025). Assessing Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Disruption: The Focus on Cross-Border Suppliers. Logistics, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010001