Abstract

Background: This study aims to analyze the relationship between lean practices and organizational performance in a public institution, specifically, a military organization. Methods: The research has a quantitative approach with a descriptive character, having as a sample the members of a military unit located in Rio Grande do Sul. A valid sample of 116 answered questionnaires was obtained. Data analysis was carried out through multivariate statistical treatment, known as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), using the Smart-PLS software. Results: At the end of the study, it was possible to confirm the central hypothesis of the study and conclude that lean practices (waste elimination, continuous improvement, support and leadership, member involvement, education and training, long-term thinking, quality, and systemic vision) positively impact organizational performance. Together, these elements combine to engender organizational effectiveness and success, promoting more productivity, quality, profitability, and customer satisfaction, thus improving the organization’s performance. Conclusions: It is evident that the members of the military unit are committed to optimizing organizational performance, showing constant improvement in productivity, rarely committing errors, cost reduction in activities and works, high effectiveness in meeting goals, prioritizing cost reduction in the execution of activities, as well as achieving goals and objectives related to the services provided.

1. Introduction

Lean practices have proven to be a promising field for the development of research aimed at analyzing organizational performance, due to their systematic and process-oriented approach to continuous improvement, which has shown an effect on the efficiency and effectiveness of organizations. Moreover, with changing customer demands and needs, companies are faced with the need to adopt an efficient management philosophy to assist with decision making and eliminate the risk of losses as much as possible [1]. According to information released by [2], a well-established organizational performance system, along with the construction of indicators, contributes to the development and achievement of results in organizations.

The measurement of organizational performance in public agencies is methodologically complex, and there are several challenges in effectively conducting this type of assessment, because there may be variations in management systems and infrastructure, market dynamics, and, especially, a difference in data in other units in the same area in local, state, and federal spheres [3,4]. When analyzing public management in Brazil, one realizes that currently, the country is experiencing instability that tends to lead to reduced expenditure in all sectors of the economy and reduced investment in public services [5]. This situation opens space for debate on the adoption of lean practices from the private sector in public management and may serve as a reference for various institutions.

The lean management approach is centered on continuous improvement in an inherently dynamic way, adding value for the customer. The definitions of value and satisfaction from the customer’s point of view, improvement of productivity levels, efficiency, as well as the elimination of waste in processes are widely discussed in academia and manufacturing organizations. However, the value of lean practices has still been little explored in public organizations [6], even with an increase in the demand for quality products and services provided to the public.

Although public organizations do not operate in the competitive business market, they also demand agility and quality of their services, which requires measures and practices that have an impact on improving organizational performance. Thus, this study aims to analyze the influence of lean practices on organizational performance in a public institution.

Several studies highlight lean management as an effective management tool [6,7,8,9,10]. However, even though there are studies that have analyzed the impacts of lean practices in public institutions, in the period searched (2014–2023), there are several references on the subject [11,12,13,14,15], but no studies were found that referred to lean practices and organizational performance in military organizations, indicating that scientifically, there is still a research gap regarding the relationship between lean practices and organizational performance, especially in military organizations, and therefore, the theme was explored in this study.

This paper innovates by analyzing the impact of lean practices on organizational performance in a public institution being carried out in a military organization. It is noteworthy that this type of institution has features that distinguish it from other “civil” public institutions, since a military organization is an institution established with the purpose of defending a country, protecting its national interests, and maintaining the security and sovereignty of the State. Among the features that distinguish military organizations from other “civilian” public institutions are hierarchy and discipline, defense and security mission, military culture and values, stability and continuity, as well as legal and international aspects.

2. Research Background

2.1. Lean Practices in Public Institutions

The lean approach is considered the most effective philosophy for substantial, relatively quick productivity improvement in any type of organization and is becoming increasingly popular with companies and public institutions [16], demonstrating itself to be an important approach for achieving competitiveness in a business environment [17,18,19]. Therefore, this approach can contribute to the current state of lean transformation in the general context of organizations [20].

With the current economic and political trends, the constant search for greater efficiency, transparency, and management in the public and private sectors is evident [21,22]. Public organizations have been undergoing significant changes and, due to current social and political circumstances, new ways of conducting processes and increasing the satisfaction of all who interact with these institutions are required [23].

It is becoming increasingly common for public administration organizations in some countries to apply an organizational matrix structure. This approach involves adopting lean practices in public administration, creating a model for rationally selecting management team members, improving developed processes, and achieving high rates of efficiency and effectiveness [24]. But the challenges currently faced by public organizations are numerous.

Among the main challenges faced in public agencies are the management of sectors with a small team or insufficient staff, short deadlines, scarce resources, and high expectations from the upper management, in a critical area for the production of efficient services where there is no well-structured, effective, and easily implemented methodology [25]. In an approach for public service, Ref. [26] states that the lean philosophy in public institutions was initially applied in health services, beginning in the United Kingdom in 2001 and the United States in 2002.

Regarding the journey of implementing lean practices in an organization, both public and private, Ref. [27] state that the application of tools and techniques should not occur gradually and must be accompanied by strong leadership. The authors reinforce that top management commitment to lean implementation is indispensable to leadership performance. In addition, employee commitment is required to be conditioned by the belief that only common engagement leads an organization to success. Ref. [26] emphasize that without the employment of a dominant service or private enterprise logic, the lean philosophy will be doomed to fail in public institutions, either as a set of managerial practices or even as a theory.

Despite the wide dissemination of the benefits of the lean philosophy in academia, many public organizations in Brazil do not put it into practice. According to [25], the use of lean does not occur because public institutions do not know or do not know how to use this organizational model, do not understand or are unaware of the benefits brought by this philosophy, or have little support from upper management. Therefore, the search for continuous improvement, waste elimination, and the construction of an effective public service are not easy tasks, requiring oriented and guided work methodologies in these institutions.

2.2. Organizational Performance

The field of studies related to the measurement and evaluation of the performance and efficiency of organizations is constantly growing. For [28,29], due to the increase in competitiveness, organizations have felt the need to use performance assessment tools to assist the decision-making process. The authors also state that the assessment of organizational performance is important because, from the results, it is possible to visualize the positive and negative points of the company, allowing the implementation of solutions and improvements in areas where deficiencies are detected. Thus, it becomes possible to optimize the results with corrective actions to achieve the established objectives.

In general, the dimensions of organizational performance seek to cover the plurality of interests in the company’s success. In public organizations, the dimensions of organizational performance can address specific aspects related to the provision of services, transparency, and responsibility with the use of resources [30,31]. In addition to financial dimensions, customers, and internal processes, it is important to consider additional dimensions, such as the evolution in service delivery, equity in access and distribution of resources, accountability, and citizen participation. Financial performance involves the efficient and responsible use of public resources, while customer satisfaction can relate to the perception of quality and accessibility of public services [32]. Additionally, internal processes must be evaluated in terms of operational efficiency, human resource management, and innovation capacity.

Unraveling how companies reach and maintain distinct positions in the market is one of the great challenges that comprise the current scenario of broad organizational competitiveness. Additionally, it is necessary to consider the rapid technological evolution that requires organizations to adapt and constantly adopt new technologies to improve their operational efficiency, innovate their products and services, and keep up to date with market demands. Still, consumer expectations are constantly changing, with greater emphasis on the personalization, quality, sustainability, and social responsibility of organizations [33,34]. The search for efficiency and effectiveness in business management aimed at circumventing this context has been increasing the visibility of the theme training and managerial performance and, therefore, organizational performance has become a significant indicator for companies to achieve their objectives or goals [35].

From the manager’s perspective, the intense transformations in the internal and external environment of organizations translate into a variety of demands that make the managerial activity more complex. The managerial capacity has been gaining prominence in the business world, as an alternative for organizations to ensure competitiveness in the market. Thus, a more comprehensive performance evaluation system tends to influence the cognition and motivation of an organization’s employees, which in turn influences their managerial performance. In the same perspective, the lean philosophy is a broad management approach that can be considered as a set of management tools or even a management system [16].

Organizational performance in public organizations can be boosted by adopting the lean management philosophy. The lean philosophy, which originated in the industrial sector, has been successfully applied in public organizations to improve efficiency, eliminate waste and improve the delivery of public services. By adopting lean principles, such as identifying and eliminating activities that do not add value, through continuous improvement and employee engagement, public organizations can reduce waiting times, streamline processes, increase transparency, and improve the quality of services offered to citizens [36]. Additionally, the lean philosophy also emphasizes the importance of employee involvement and empowerment, encouraging collaboration, teamwork, and the search for innovative solutions [1,6,37].

However, changing traditional management behavior requires a change in mindset and, essentially, a change in how leaders allocate their time every day. For [17], the essential role of the leader, including lean leadership behavior, can be described as an integral part of a lean management system and a problem-solving culture. The adoption of Lean philosophy in an organization implies several paradigm changes, not only in the processes, but also in the way people interact, requiring new leadership skills. However, it is important to establish performance indicators to enable a detailed analysis of relevant aspects.

2.3. Theoretical Research Model

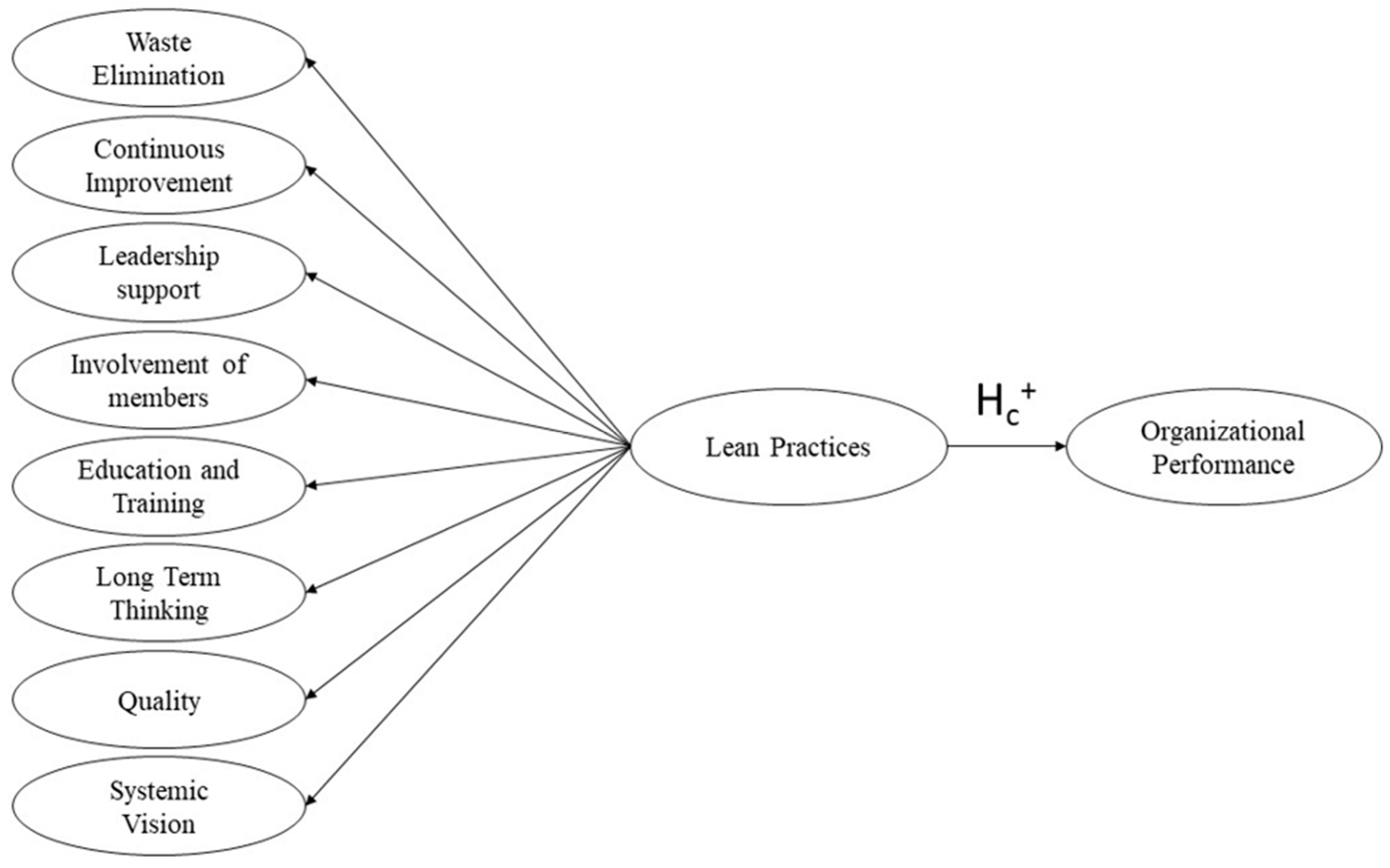

The conceptual framework of this study, presented in Figure 1, proposes that lean management practices positively influence organizational performance. The lean practice determinants in the study are made up of latent variables that function as operational variables (waste elimination, continuous improvement, support and leadership, member involvement, education and training, long-term thinking, quality, and systemic vision).

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

This study was developed to show that lean practices have predictive validity in organizational performance. Lean philosophy is a way of specifying a value to the process, performing activities without interruption every time someone requests them, and in an increasingly effective format, providing customers with what is desired [6,19]. Ref. [9] emphasize that lean strategies, in addition to playing an important role in reducing waste and non-value-added activities throughout the organization, also increase the ability to use and analyze data in processes and organizational performance.

The elimination of waste is one of the main premises of lean practices and its influence on organizational performance has been widely studied. By eliminating activities that do not add value to the product or service offered by the organization, it becomes possible to reduce costs and increase process efficiency, significantly improving the quality of products or services provided to customers [29]. As for continuous improvement, [38,39] describe that it consists of a methodology used to improve the efficiency, flexibility, and quality of their production operations, mainly regarding the competitiveness of organizations.

In addition, leadership support plays an important role in the performance of organizations. For [6,40], waste reduction and success in implementing lean in public institutions have a strong relationship with constant and permanent thinking about improvements in sectors or departments by managers and leaders. Complementarily, that organizational member engagement is a critical factor for successful organizational performance. When organizational members feel engaged and motivated by the work they do, they are more likely to strive for positive outcomes for the organization [41]. This translates into higher productivity, quality of work, and customer satisfaction.

Regarding education and training, Ref. [42] states that the different areas of performance and skills combined with the absence of individualized training policies can lead to demotivation and loss of interest by the staff. Because of this, the stimulus for updating knowledge and offering training provides preparation in key task-oriented skills [43] that, in the organizational daily life, contribute to professional development and growth [44].

Long-term thinking is a strategic approach that is increasingly valued in the organizational environment. Rather than focusing solely on short-term goals, organizations that adopt long-term thinking seek to create sustainable value for all stakeholders, including customers, employees, financial backers, and the community [45]. This strategic approach can demonstrate a positive influence on organizational performance as it allows companies to adapt to market changes and maintain long-term competitiveness.

Quality is also a fundamental aspect of organizational performance, ensuring that the products or services offered meet or exceed customer expectations, in addition to reducing costs and improving process efficiency [46]. Moreover, the constant search for quality improvement is an important strategy to increase customer satisfaction and improve their confidence in the market [47].

The systemic view consists of a strategic approach that considers the organization as an interdependent system of parts that work together to achieve a common goal. This approach allows organizations to visualize the different processes, people, and departments for more integrated and efficient decision-making, enabling the identification of opportunities for improvement in all aspects [48]. Thus, it enables an increase in process efficiency, the quality of products or services, cost reduction, and in the increase in customer satisfaction, in addition to promoting integration among the teams and encouraging group work and knowledge sharing [49].

Consequently, it is suggested that one of the alternatives to improve organizational efficiency and effectiveness is the adoption of lean philosophy and practices. Based on the above, the central hypothesis of the study is presented:

Central Hypothesis: Lean practices positively affect organizational performance.

3. Materials and Methods

This research is based on a quantitative approach with a descriptive character, with the application of a survey. The population of this study is represented by the members of a military unit located in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, totaling around 450 individuals. This population is included from the soldiers to the commander since the lean philosophy bases its activities on the people directly involved in the execution of the activities. The research sample is characterized as non-probabilistic, intentionally selected by accessibility. This type of sampling selects a group of respondents from a larger population, being aware that some members of the population have no chance of responding to the survey.

A valid sample of 116 answered questionnaires was obtained. The descriptive data on the respondents’ profile analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of respondents according to variables: age, sex, level of education, and length of service.

The profile of the respondents indicates that most of the participants are between 19 and 55 years old, and most of them are male (99%). As for the level of education, it can be seen that most of the participants (43.1%) have a high school education, while 5.9% have only an elementary school education. Regarding the length of service, 19.6% of the participants have worked for more than 10 years in their respective military unit, 23.5% have worked from 5 to 10 years, and 56.9% have worked for less than 5 years.

As for data collection, a structured questionnaire was used and data collection occurred in December 2020 and January 2021 via an online questionnaire via Google Forms. Table 2 presents the information of the constructs and variables that comprised the research questionnaire. The measure used to evaluate the responses was a Likert-type scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Table 2.

Constructs and variables that comprised the research questionnaire.

The research data were exported in a spreadsheet format. After tabulation and the referred adjustments, the spreadsheet was saved in CSV format so that the statistical treatment could be performed by the Smart-PLS software, which, according to [57], allows modeling the latent variables with formative indicators instead of reflective indicators in structural models.

Following the logic of [58], multivariate structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied. This type of statistical technique allows a better understanding of the observed practical variables by explaining the relationships between the dependent and independent variables through the estimation method of partial least squares, using the Smart PLS-PM (Partial Least Square) software version 3.0 [59]. It is also noteworthy that PLS-SEM is recognized as a superior alternative when compared to the isolated application of PLS [60].

The SEM Path Diagram was developed, with the direction of the arrows inserted in said diagram indicating the type of relationship between the variables, which can be reflexive when changes in the latent variable generate changes in the observed variables or formative when changes in the observed variables generate changes in the latent variable [57,61].

Data analysis followed the SEM procedures described by [56]: (i) measurement model evaluation, in which the identification of an initial model with its constructs and indicators is prepared; (ii) reflective measurement model evaluation: indicator reliability should be equal or greater than 0.7; composite reliability should be equal or greater than 0.7; Cronbach’s alpha equal or greater than 0.7; AVE equal or greater than 0.5; and the analysis of factor loadings by the [62] method; and (iii) evaluation of the structural model by analyzing the R2 and the f2 effect using bootstrapping to analyze significance; relevance of Q2 has to be greater than 0, and predictive relevance is considered small (0.02), medium (0.15) and large (0.35), calculated using blindfolding.

4. Results and Discussion

The data were quantified and tabulated after the online questionnaire responses were received, as described in the previous section. Then, SEM was performed. The average variation that a latent construct was able to explain the observed and theoretically related variables was verified through the analysis of extracted variance (AVE). As three constructs with AVE below 0.50 (waste elimination—ED, continuous improvement—MC, and quality—Q), the variables with factor loadings below 0.50 were excluded, being, respectively, the variables ED4, MC2, and Q5. With the exclusion of the aforementioned indicators, the measurement model assumed new values, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analysis of convergent validity (AVE), composite reliability, and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha).

The AVE results for the constructs confirm the convergent validity of the model (AVE above 0.50) and the tests for internal consistency analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha above 0.70) and composite reliability (above 0.70) are adequate and satisfactory, as recommended by [61].

After the adjustments and based on discriminant validity analysis, it was identified that all constructs have higher factor loadings in their respective variables than in the other constructs, as recommended by [62], indicating that the latent variables are independent of each other. The results of discriminant validity are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity results.

That the convergent discriminant validity is performed to measure the level of correlation of multiple indicators of the same construct that are in agreement [62]. Thus, we proceeded to the next step, which is the predictive relevance analysis (Q2), in which we verified the accuracy of the model after the adjustments [58], considering that constructs with Q2 greater than zero indicate that the model has predictive validity. Regarding the effect size, using Cohen’s indicator (f2) in which it is evaluated how much each construct is useful for the model adjustment [63], we found that all values were greater than 0.35, indicating that all constructs are useful to the model adjustment. Table 5 highlights the values of Q2 and the f2 obtained for the model.

Table 5.

Q² and f² values obtained for the model.

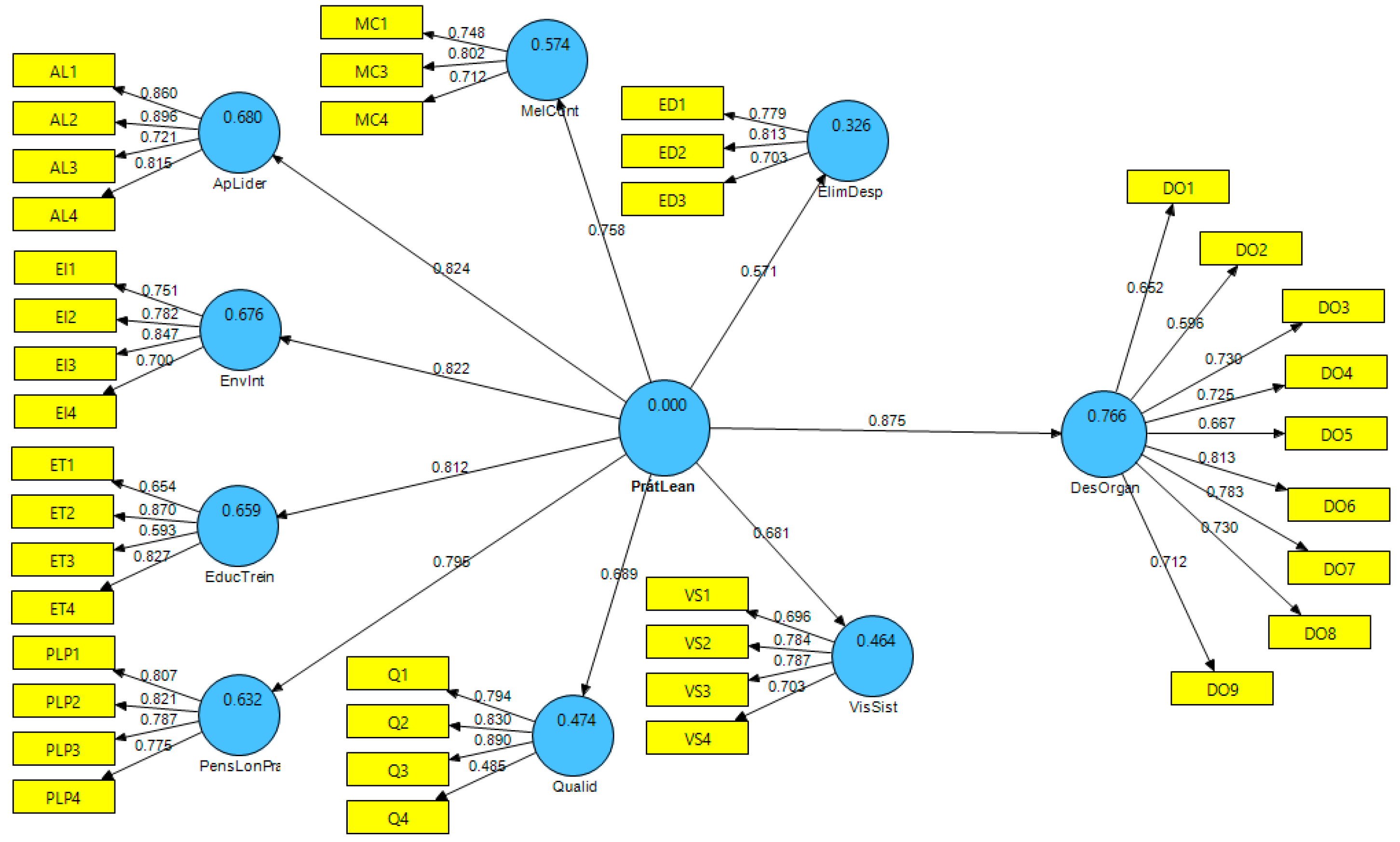

Figure 2 represents the final integrated model.

Figure 2.

Final integrated model.

To verify the quality of the adjustments of the final model, the R2 and the goodness-of-fit (GoF) were used [64]. The R2 represents on a scale from 0% to 100% of how much the independent constructs explain the dependent ones. Table 6 presents the result of the structural model, where it can be seen that there was a significant and positive influence of lean practices on organizational performance, and the better the lean practices, the better the organizational performance tends to be.

Table 6.

Q² and f² values obtained for the model.

With the final integrated model, it was possible to verify the hypothesis tested in the study and find that it was confirmed, indicating that lean practices (waste elimination, continuous improvement, support and leadership, member involvement, education and training, long-term thinking, quality, and systemic vision) significatively impact organizational performance. This result is linked to the fact that waste elimination, for example, seeks to identify and eliminate activities or processes that do not add value, generating greater efficiency and productivity. Continuous improvement, in turn, seeks to continuously improve processes, products, and services, promoting innovation and adaptation to market changes [65]. Support and leadership are fundamental to creating a motivating and engaged work environment, encouraging employee participation and collaboration. The involvement of the member stimulates the autonomy, responsibility, and commitment of the organization’s members, promoting collectivity and a sense of belonging [29].

In addition, education and training enable the development of employee skills and competencies, effectively their performance and ability to deal with challenges [66]. Long-term thinking involves strategic planning and decision-making taken in long-term goals, considering the impact of actions on the future of the organization [67,68]. Quality is a key factor to ensure customer satisfaction and support the organization, involving process control and the pursuit of excellence. The systemic vision allows an understanding of the emotions and interdependencies between the different elements of the organization, promoting the integration and optimization of resources [29]. Together, these elements create organizational effectiveness and success, promoting more productivity, quality, profitability, and customer satisfaction, and thus improving the organization’s performance.

The lean philosophy is a way to specify the value of the production process, aligning the best sequence of actions that create it, performing activities without interruption every time someone requests them, and in an increasingly effective way, providing customers with what is desired [16,19]. To achieve the productivity potential of organizations and the development of people, in addition to training and capacity building, the process of communication and feedback is essential, providing the construction of attractive environments that are productive and capable of engaging people [69].

Long-term thinking can help organizations improve processes by providing beneficiaries with what they expect, consisting of a process that respects their time, is error-free, and is available to the beneficiary [70]. Long-term thinking is a strategic approach that has been shown to have a positive influence on organizational performance as it enables adaptations to market changes and long-term competitiveness [45]. Ref. [25] further conclude that continuous improvement, waste elimination, and building effective public services are not easy tasks, requiring targeted and guided work methodologies in these institutions.

It should be noted that military organizations are characterized by a rigid hierarchical structure, where authority is clearly defined and members are expected to obey the orders of their superiors [71,72]. Discipline is a core value and following the chain of command is essential to the effective functioning of military operations [72,73]. In addition, the main mission of military organizations is the defense of the country and the security of its citizens. Unlike civilian institutions, the military is constantly involved in training, planning, and executing military operations [71].

Furthermore, military organizations have their own culture and procedures, which include specific values and norms to perform tasks and activities. These values often include loyalty, discipline, commitment, courage, honor, satisfaction, and teamwork. Military culture also emphasizes discipline, professional ethics, and a deep sense of duty to the country and its citizens [73,74]. Nonetheless, military organizations are designed to be enduring, able to meet long-term challenges, and maintain national security in all circumstances. They have stable organizational structures, well-defined leadership succession processes, and contingency plans to ensure continuity of operations in times of crisis [70,74]. All these characteristics make military organizations unique and derived from an organizational system based on principles strongly rooted in its chain of command. But despite this, the results of this work demonstrate how these organizations can improve their performance without giving up these deeply embedded principles and values.

Nevertheless, military organizations have functional peculiarities arising from their vertical management structure and their relationship with the federal administration. The structure of the army is favorable for the effective establishment of command, direction, and discipline [11]. However, when it comes to promoting cultural change in an organization that encompasses both military and civilian personnel, the transformation process becomes more challenging [11,13]. The coexistence of different organizational cultures and work approaches can create resistance to change and require additional effort to align values, goals, and practices to achieve effective synergy and drive the desired transformation.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between lean practices and organizational performance in a public institution, using as a population the members of a military unit located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Thus, it is inferred that there is a relationship between lean practices and organizational performance, showing that these practices have a positive impact on improving organizational performance in the military unit studied, and possibly in other similar public institutions. These results may be justified by the fact that the Brazilian Army is focused on discipline, organization, solidarity, training, and a sense of duty, among other characteristics of its members, besides aligning the focus of the characteristics with the knowledge and achievement of the army’s mission.

In general, the elimination of waste provides the identification and elimination of activities or processes that do not add value, generating efficiency and productivity. Continuous improvement seeks to constantly improve processes, products, and services, promoting innovation and adaptation to market changes. Organizational support and leadership encourage people’s commitment and engagement, stimulating employee participation and collaboration. The involvement of the members promotes autonomy, responsibility, and commitment, stimulating collectivity and a sense of belonging. Education and training develop skills and competencies, improving performance and the ability to deal with challenges. Long-term thinking involves strategic planning and decisions determined by long-term goals, considering the future impact. Quality ensures customer satisfaction and the pursuit of excellence, while systemic vision promotes integration and optimization of resources. These elements are essential to organizational performance, driving the achievement of objectives efficiently and effectively.

In this sense, it was evident that the members of the military unit are committed to organizational performance, showing constant improvement in productivity, a rarity in making mistakes, cost reduction in activities and works, high effectiveness in meeting goals, prioritizing minimum cost in the execution of activities, as well as, seeking to achieve the goals and objectives with the performance of services provided. Among the limitations of the research, it is noteworthy to describe that it was not possible to be closer to the members to reach a larger sample size due to the pandemic situation. As for future studies, it is suggested that the survey be applied to all military units in Brazil, making a comparison between sample sizes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.I.S.; methodology, P.I.S. and L.L.K..; software, P.I.S.; validation, P.I.S., L.L.K. and E.d.O.S.; formal analysis, P.I.S.; investigation, P.I.S.; resources, P.I.S., L.L.K. and E.d.O.S.; data curation, P.I.S. and L.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.I.S.; writing—review and editing, P.I.S., L.L.K. and E.d.O.S.; visualization, P.I.S., L.L.K. and E.d.O.S.; supervision, L.L.K. and E.d.O.S.; project administration, P.I.S., L.L.K. and E.d.O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Juliani, F.; Oliveira, O.J. Lean six sigma in the public sector: Overcoming persistente management challenges. Qual. Manag. J. 2021, 28, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirau, T.J.; Blaser-Mapitsa, C. How performance management regulations shape evaluation practice in South African municipalities. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 82, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, J.; Marconi, K.; Mannle, T.E., Jr. Developing a performance management system for a Federal public health program: The Ryan White CARE ACT Titles I and II. Eval. Program Plan. 2011, 24, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, L.; Petry, I.S.; Matos Frossad, L.B.; Isidro, A. Avaliação de competências organizacionais de órgão público federal: Ótica de diferentes atores. RACE-Rev. Adm. Contab. E Econ. 2021, 20, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.A.; Schwantz, P.I.; Moretto Neto, L. Análise do plano de contingência da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz para o enfrentamento do Coronavírus. Ciências Adm. 2021, 23, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.P.L.; Galina, S.V.R.; Grande, M.M.; Brum, D.G. Lean thinking: Planning and implementation in the public sector. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2017, 8, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Gimenez, C.; Fynes, B.; Wiengarten, F.; Yu, W. Internal lean practices and operational performance: The contingency perspective of industry clockspeed. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 562–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Dixit, A.R.; Qadri, M.A. Impact of lean practices on performance measures in context to Indian machine tool industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 26, 1218–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habidin, N.F.; Mohd Yusof, S.; Mohd Fuzi, N. Lean Six Sigma, strategic control systems, and organizational performance for automotive suppliers. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2016, 7, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Fathi, M.; Fontes, D.B.M.M.; Tan Ching, N. Modeling lean manufacturing success. J. Model. Manag. 2018, 13, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.B.; Seraphim, E.C.; Agostinho, O.L.; Lima Junior, O.F.; Batalha, G.F. Lean office in health organization in the Brazilian Army. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2015, 6, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, R.; Torralba, M.; Pérez-Moya, R.; Pozo, J.A. Value stream analysis in military logistics: The improvement in order processing procedure. Appl. Sci. 2019, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, N.; Hines, P.; Davidson, P. Wider applications for Lean: An examination of the fundamental principles within public sector organisations. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2014, 63, 550–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, V.R.; Raju, R.J.I.J. A systematic literature review of Lean Six Sigma in different industries. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2016, 7, 430–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim Suhag, A.; Solangi, S.R.; Larik, R.S.A.; Lakh, M.K.; Tagar, A.H. The relationship of innovation with organizational performance. Int. J. Res.-Granthaalayah 2017, 5, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, W. The Lean Management Maturity Self-Assessment Tool Based on Organizational Culture Diagnosis. Procedia Soc. Behavional Sci. 2015, 213, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, N.M. Current and future global challenges in management and leadership: Finance and quantum computing. In Paradigm Shift in Management Philosophy: Future Challenges in Global Organizations; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. O Sistema Toyota de Produção: Além da Produção em Larga Escala; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. A Mentalidade Enxuta nas Empresas Lean Thinking: Elimine o Desperdício e Crie Riqueza, 1st ed.; Campus: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Benkarim, A.; Imbeau, D. Organizational commitment and lean sustainability: Literature review and directions for future research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velsberg, O.; Westergren, U.H.; Jonsson, K. Exploring smartness in public sector innovation-creating smart public services with the Internet of Things. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yami, M.; Ajmal, M.M. Pursuing sustainable development with knowledge management in public sector. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 49, 568–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão Junior, M.A.G.; Santos, R.N.M. A gestão de processos na análise das atividades de seleções públicas simplificadas: Estudo de caso em uma prefeitura. Navus Rev. Gestão E Tecnol. 2016, 6, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leontjeva, O.; Trufanova, V. Lean Team Members’ Selection for Public Administration Organisations. Public Adm. Issues 2018, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, J.L.S.; Ferraz, F.T. Implantação da Metodologia “Lean” nos setores de Serviços Gerais de uma instituição federal de ensino. In Anais VII Congresso de Sistemas Lean: Contribuições do Lean à Gestão em Tempos de Crise; 10 e 11 de Novembro de; Niterói/Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017; Available online: http://www.producao.uff.br/lean7/anais.html (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Radnor, Z.; Osborne, S.P. Lean: A failed theory for public ervices? Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibia, I.K.; Dhakal, H.N.; Onuh, S. Lean “Leadership People Process Outcome” (LPPO) implementation model. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, C.S.; Shio, E.; Santos, L.A. O desempenho organizacional por meio da contabilidade gerencial quanto a utilização de ferramentas de gestão. Discip. Sci. 2017, 12, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, A.B.; Dahiyat, S.E.; Matsui, Y. Lean management and innovation performance. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, D.S.; Zaroni, A.N.; Yusuf, M. Actualization of Performance Management Models for the Development of Human Resources Quality, Economic Potential, and Financial Governance Policy in Indonesia Ministry Of Education. Multicult. Educ. 2023, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal, D.A.; Rerup, C. The plural of goal: Learning in a world of ambiguity. Organ. Sci. 2021, 32, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Saliterer, I.; Steccolini, I. Digitalization, accounting and accountability: A literature review and reflections on future research in public services. Financ. Account. Manag. 2022, 38, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A.; Ikram, M. Steering firm performance through innovative capabilities: A contingency approach to innovation management. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, C.; Dibb, S.; Meadows, M. Leveraging Big Data for Strategic Marketing: A dynamic capabilities model for incumbent firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 190, 122402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Mohamed, R.; Ayoup, H. The mediating role of organizational capabilities between organizational performance and its determinants. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi, M.H.M.; Juniati, S.; Kozicka, K.; Razimi, M.S.A. Influence of lean practices on supply chain performance. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, V.; Hu, G. Improving manufacturing supply chain by integrating SMED and production scheduling. Logistics 2021, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arca, J.; Prado, J.C. Systematic personnel participation for logistics improvement: A case study. Hum. Fac. Erg. Man. Serv. Ind. 2010, 21, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, H. Continuous improvement philosophy—literature review and directions. Benchmarking Int. J. 2015, 22, 75–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterbury, T. Learning from the pioneers: A multiple-case analysis of implementing Lean in higher education. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2015, 32, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabagi, N.; Croteau, A.M.; Audebrand, L.K.; Marsan, J. Gig-workers’ motivation: Thinking beyond carrots and sticks. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, R.; Gisbert, M.R.S.; Poler, R. Conceptualisation of the three-dimensional matrix of collaborative knowledge barriers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprinkle, T.A.; Urick, M.J. Three generational issues in organizational learning: Knowledge management, perspectives on training and “low-stakes” development. Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Wrzosek, M.; Krajewska, D.K.; Krajewski, K. Risk of food losses and potential of food recovery for social purposes. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W.; Koller, T.; Nuttall, R. Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Co. 2019, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Santa, R.; Macdonald, J.B.; Ferrer, M. The role of trust in e-Government effectiveness, operational effectiveness and user satisfaction: Lessons from Saudi Arabia in e-G2B. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, R. Improving Product Quality and Satisfaction as Fundamental Strategies in Strengthening Customer Loyalty. Akad. J. Mhs. Ekon. Bisnis 2022, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Gaba, V. Organizational structure, information processing, and decision-making: A retrospective and road map for research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Huo, B. The effect of high-involvement human resource management practices on supply chain resilience and operational performance. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2023, 8, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingelsson, P.; Mårtensson, A. Measuring the importance and practices of Lean values. TQM J. 2014, 26, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhieh, L.; Abdallah, A.A. A two-way causal chain between lean management practices and lean values. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, M.P.; Shalij, P.R.; Ramesh, A. Lean manufacturing practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs and their effect on sustainability performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 772–793. [Google Scholar]

- Sfakianaki, E.; Kakouris, A. Lean thinking for education: Development and validation of an instrument. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 917–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.C.O.; Lima, E.P.; Costa, S.E.G. Produtividade sistêmica: Conceitos e aplicações. Production 2014, 24, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F.H.B.; Alvarez, L.D.C.H. A aplicação da filosofia Lean Thinking nos setores de saúde: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2022, 15, e10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenshinov, Y.; Al-Ali, A. The tools of increasing efficiency of human resource in the lean production environment: Conceptual study. Int. J. Core Eng. Manag. 2020, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Silva, D.; Bido, D.S. Modelagem de equações estruturais com utilização do SmartPLS. Rev. Bras. De Mark. 2014, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 1st ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira Neto, G.C.; Tucci, H.N.P.; Correia, J.M.F.; Silva, P.C.; Silva, D.; Amorim, M. Stakeholders’ influences on the adoption of cleaner production practices: A survey of the textile industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M.; McIntosh, C.N.; Antonakis, J.; Edwards, J.R. Partial least squares path modeling: Time for some serious second thoughts. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 47, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Ringle, C.M.; Schlägel, C. A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 376–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Amato, S.; Vinzi, V.V. A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modeling. In Proceedings of the XLII SIS Scientific Meeting; CLEUP: Padova, Italy, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 739–742. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assen, M.F. Empowering leadership and contextual ambidexterity–The mediating role of committed leadership for continuous improvement. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaean, F.; Ali, K. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership and learning orientation on organizational performance of SMEs: The mediating role of innovation capacity. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadi, M.J.; Eskandari Dehdazzi, R. Investigating the role of strategic thinking in establishing organizational excellence model: A moderating role of organizational forgetting. TQM J. 2019, 31, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, E. Pandemics and environmental shocks: What aviation managers should learn from COVID-19 for long-term planning. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 90, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, J.I.; Fumagalli, L.W.A. o feedback como processo de aprendizagem organizacional. Rev. FAE 2018, 21, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Ozkan-Ozen, Y.D. Lean in higher education: A proposed model for lean transformation in a business school with MCDM application. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2019, 27, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermier, J.M.; Berkes, L.J. Leader behavior in a police command bureaucracy: A closer look at the quasi-military model. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malešević, S.; Ó Dochartaigh, N. Why combatants fight: The Irish Republican army and the Bosnian Serb army compared. Theory Soc. 2018, 47, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţuţuianu, D.E. Discipline and Its Subsequent Benefits for Teaching English in Military Institutions; Bulletin of “Carol I” National Defence University (EN); “Carol I” National Defence University (EN): Bucharest, Romania, 2017; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Clark, B.N.; Wright, E.C.; Fina, B.A.; Blount, T.H.; Evans, W.R.; Carreño, P.K.; Peterson, A.L.; Foa, E.B. Military culture considerations in prolonged exposure therapy with active-duty military service members. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2019, 26, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).