Abstract

Background: In this essay, we address an important issue in the logistics education discourse relating to student-centered curriculum design and evaluation. Methods: We adopt an integrative approach based on conceptual development and guided by constructive alignment. Results: We apply and elaborate our conceptual framework using a case of a teaching plan in logistics management. We also propose an evaluation strategy for our teaching plan in the form of a template. Conclusions: Our essay contributes to the logistics education discourse by using learning theories and developing curriculum design and evaluation guidelines that can be replicated by other educators.

1. Introduction

A key responsibility of logistics educators is designing effective and authentic curricula and learning experiences for students [1]. As with any product/service development initiative, there is a chain of tasks and activities involved in the process of curriculum design and evaluation. What can significantly enhance the success of the final product is its alignment with students’ educational needs, wants, and desires [1,2]. In essence, a student-centered design can assist the educator in making informed decisions on coordinating and integrating the chain of tasks and activities required for the successful development of logistics subjects. According to Hannafin et al. [3], student-centered learning promotes taking ownership of learning based on self-created learning opportunities and dynamic knowledge reconstruction.

Central to the above narrative is the notion of “constructive alignment”, which can be extremely useful for logistics educators to synchronize elements such as intended learning outcomes (ILOs), teaching and learning activities (TLAs), and assessment tasks (ATs) within the curriculum design [4]. Biggs and Tang [5] define ILOs as “…statements, written from the students’ perspective, indicating the level of understanding and performance they are expected to achieve as a result of engaging in the teaching and learning experience” (p. 100). As such, ILOs drive the strategic direction of a subject in terms of its TLAs and ATs. It is very important that ILOs are developed with careful attention to ensure that logistics students will obtain the required knowledge and skills after completing a particular unit of study [6].

Despite the growing interest among students and employers in issues related to logistics management, we lack an integrative understanding of what constitutes a student-centered, constructively aligned curriculum design for logistics education [7]. This has the potential to undermine the uptake of authentic learning and teaching despite the increasing industry demand for talent and the prevalence of 21st-century skills. Equally important is that we advance our understanding of how such authentic curriculum design can be practiced and its effectiveness evaluated by education and other stakeholders. This is an important shortcoming, in particular within the emerging literature that focuses on educational developments and, as such, warrants further contributions from the logistics education community. Such contributions allow for improving teaching and learning practices in logistics management and offer practical educational solutions, especially for junior faculty, to ensure student learning is not only effective but also authentic.

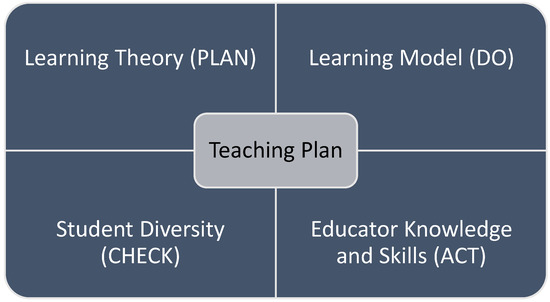

Consequently, the aim of our essay is twofold: first, we develop a conceptual framework employing the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle as one of the widely known continuous improvement models. As such, we build on the literature to integrate learning theory (plan), learning model (do), student diversity (check), and educator knowledge and skills (act) as key factors informing student-centered, constructively aligned curriculum design. We develop and use a teaching plan for an undergraduate subject on logistics management to elaborate our conceptual framework. Second, we develop a template to evaluate the effectiveness of our teaching plan that focuses on key stakeholders, potential uses, methods/sources, criteria, and required resources/skills/timeframe. We also offer suggestions for empirical validation of our proposed template in future research. Our essay makes significant contributions to the logistics education theory and practice by developing curriculum design and evaluation guidelines that can be easily replicated by logistics educators.

2. Conceptual Development

Figure 1 illustrates our developed conceptual framework, grounded in a review of the pertinent literature (e.g., [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]). We argue that this framework assists in advancing our understanding of the key factors that influence the student-centered design of curriculum and learning experiences. We use this framework to justify development of the logistics management teaching plan followed by a discussion on an evaluation template that can be used to critique the same teaching plan.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Our conceptual framework serves at least two interrelated purposes: first, it can explain the rationale for the curriculum design adopted by any educator, and second, it manifests key areas of concern when students are dissatisfied with their learning experience or have faced difficulties achieving the ILOs within a given curriculum design.

Further, the key premise of our conceptual framework can be summarized as follows: when convergence and congruence manifest across factors such as learning theory, learning model, student diversity, and educator knowledge/skills, the success of teaching and learning design will substantially improve. The latter corroborates the importance of alignment of the teaching plan with the factors shown in Figure 1 to establishing a better student learning experience.

From the quality management perspective, our conceptual framework resembles the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle [15]. Learning theory establishes a broad strategy (Plan) and the learning model provides instructions for operation (Do). These instructions need to be aligned with the student cohort and diversity factors (Check) and eventually delivered through an educator who has the right knowledge and skillset within the subject matter (Act). A discussion of each component of our conceptual framework (see Figure 1) follows.

2.1. Learning Theory

Theories play a pivotal role in explaining, describing, and predicting environmental, organizational, and human behaviors [10,11]. The rigorous, cumulative scientific discourse that underpins theory construction makes it capable of providing an instrumental framework of understanding and a guide for practice [10].

A number of learning theories have been discussed within the literature, such as behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, situated learning, connectivism, and complexity. We subscribe to the tenets of constructivism, which asserts that individuals create their own meanings through the information given to them, both through their individual assimilation and accommodation of the material [16] and through collaborative dialogue with their peers [17]. The latter can fuel the broad strategy (Plan) of the curriculum designer and, more specifically, his/her decisions in terms of selecting the appropriate learning model, integrating student diversity into the learning environment, and leveraging knowledge and skills to deliver impactful learning.

2.2. Learning Model

Learning models provide a systematic account of different curriculum design practices that can be adopted by educators (Do). These learning models are often a mixed reflection of the learning theories and the educators’ experiences over the course of their careers. For example, objective models [18] offer a static view of design whereas interaction models [19] perceive design as a context-specific phenomenon with some level of fluidity that follows a temporal path towards its alignment with students’ learning requirements. Other learning models, such as the naturalistic model [20], argue that curriculum design should be a function of the collective intelligence, where a consensus-based platform of ideas and shared beliefs can be established to draw overarching goals and pathways for a particular curriculum.

Integrating some of the key premises of the above-noted learning models, the backward model [1] offers a broad, student-centered approach to curriculum design. This model is similar to the objective model in that its prime attention is on the key goals, objectives, and learning outcomes (desired results) that students will need to obtain. It basically portrays the destination first and then seeks the most effective route to reach that destination. However, the backward model is also context-specific, as it embraces design emerging from the context in which the curriculum is constructed [2]. That is why, for example, in the backward model the ATs are designed after the determination of ILOs. The development of learning events does not occur until the last stage of backward model implementation.

2.3. Student Diversity

Diversity, as its name reflects, is a multidimensional concept. Understanding and appreciating diversity becomes even more complex when viewed in relation to higher-education students, as a number of dynamics, such as prior knowledge, learning conception, studying approaches, and established expectations, are at play [21]. While these types of dynamics are largely beyond institutional control [22], educators have the opportunity to integrate them into their chosen learning model (Check). This has the potential to increase the level of student satisfaction with their curriculum, as they can better relate to the contents.

2.4. Educator Knowledge and Skills

Without the right knowledge and skills (both research and teaching), even the best-designed teaching plans, well informed by learning theories and models and well aligned with student diversity, could easily fail. That is why an excellent teaching plan requires an excellent educator with the necessary knowledge, style, and character to enable impactful teaching and student engagement. Therefore, an extremely important issue that affects the design and delivery of the teaching plan is ensuring that the educator has sufficient background and expertise in teaching the subject area and the capability to lead and manage diverse cohorts of students (Act).

3. Elaboration of the Conceptual Framework

We apply and elaborate our conceptual framework (see Figure 1), using the case of a teaching plan for the subject of logistics management, developed and implemented by the authors as part of an undergraduate course in the Bachelor of Supply Chain Management. Our teaching plan is informed by the constructivism theory and backward design model (see Table 1), with careful attention to the requirements of higher-education student cohorts and the relevant knowledge and skills of the educator. In order to identify desired results for the logistics management subject, four questions have been answered to support the implementation of the PDCA cycle. These are further explained in the following sections.

Table 1.

Teaching Plan Stage 1—Identify desired results.

3.1. Evidence for Learning Theory (Plan)

This aspect of our conceptual framework is embedded throughout stages 2 and 3 of the teaching plan (see Table 2 and Table 3). For example, performance task 1 would require both individual orientation, through reading the case study and addressing the allocated questions, and group (social) interaction, in which students need to discuss among themselves, finalize their responses, decide on the role of team leader, and the like. There is a discernible effort to create an opportunity for students to bring their own experiences into the discussion. With the educator facilitating, students will be able to meaningfully build on their existing knowledge of logistics management and newly learned concepts/theories through discussion with groupmates and the educator [11].

Table 2.

Teaching Plan Stage 2—Determine acceptable evidence.

Table 3.

Teaching Plan Stage 3—Plan learning experiences.

3.2. Evidence for Learning Model (Do)

This aspect of our conceptual framework encompasses the overall structure of the teaching plan. A backward design model is used, based on three stages: desired results (Table 1), assessment evidence (Table 2), and learning plan (Table 3) [1]. This model is further developed in light of both social and cognitive constructivism.

3.3. Evidence for Student Diversity (Check)

Given that the subject of logistics management is offered to final-year undergraduate students, the teaching plan is developed bearing in mind the ideas of andragogy [23]. Accordingly, we were cognizant of the fact that adult learners’ education needs and wants require a paradigm shift in teaching and learning schemes in order to be more effective and sustainable [23]. Andragogy recognizes that transformation in people’s self-concept over the years has the potential to make them dependent and self-directing [23]. The information in Table 1 (stage 1—identify desired results) provides substantial evidence for such recognition. For example, reviewing the knowledge and skills that students will acquire through the subject, it can be observed that “high-level” abilities are catered to. Examples include:

- Develop a coherent and cost-effective logistics plan for a complex business operation.

- Articulate the reasoning behind logistics decisions, giving a balanced justification for the basis of decisions.

This is aligned with the requirements of the final-year undergraduate student cohort, who are close to graduation and need analytical abilities, such as logistics planning, as well as assessment and decision-making skills, such as understanding and articulation of the reasoning behind some of the logistics practices undertaken by organizations.

Further, students’ desire for developing their social and communication skills is addressed by a number of group-based performance tasks and learning events. Group work also assists students in practicing different roles in managing conflicts and exercising accountability, time management, commitment, and leadership skills.

3.4. Evidence for Educator Knowledge and Skills (Act)

The educator of the logistics management subject must have a Ph.D. degree in a cognate area (i.e., logistics and/or operations management) or at least a master’s degree accompanied by significant relevant industry experience. This ensures that the educator has the right knowledge and skills to successfully deliver the curriculum.

4. Teaching Plan and Achieving ILOs

Our use of the backward learning model [1] in the design of the teaching plan provides a foundation for supporting students in achieving ILOs. This is further assisted by the recognition and use of the constructive alignment approach [9] in building performance tasks and learning experiences. Learning is constructed based on what activities the students perform, not what the educator does. Similarly, ATs are about how well students achieve the ILOs, not how well they report back what the educator has taught them [9].

For example, reviewing the learning events related to week 2 (see Table 3), one can observe that to achieve ILOs such as …

- Understand the key logistics concepts and analyze the issues affecting the movement of goods, services, and people (comprehension, from Bloom’s [24] taxonomy)

- Describe the complex business environment in which logistics decisions are made (comprehension) and analyze how logistics plans can be adapted in response to changes in the environment (analysis).

… the following learning events are designed:

- Establish discussion on the nature of logistics demand and how it influences individual companies in the economy. Note: It may be helpful to ask students to consider companies they have worked for or have detailed knowledge of. (Student-centered and supporting both ILOs.)

- Ask students to debate, based on their knowledge and industry experience, the following statement: Logistics is the most important economic factor for economic development. (Student-centered and supporting the first ILO.)

- Have student groups read Case 1–2 “Clearfield Cheese Company Case” from their textbook (page 28) and suggest at least two strategies to improve the case company’s competitive situation. (Student-centered and supporting both ILOs.)

- Play the video Premier Unveils Reference Design for East West Link Project. Ask students to discuss the potential transport-related implications of the project discussed in the video for the operation of both manufacturing and service companies in the state of Victoria. (Student-centered and supporting the second ILO.)

Furthermore, reviewing performance task 2 (see Table 2), one can observe that in order to assess ILOs such as …

- Develop a coherent and cost-effective logistics plan for a complex business operation.

- Articulate the reasoning behind logistics decisions, giving a balanced justification for the basis of decisions.

… the team report is designed to examine how well students can develop, articulate, and justify logistics issues and problems in a specific industry setting. This clearly demonstrates attention to assessing students’ ability to apply and synthesize concepts/theories rather than simply requiring them to explain the contents back to the educator.

So far, we have elaborated our conceptual framework (and established that it is student-centered and follows constructive alignment) based on the teaching plan for the subject of logistics management. Next, we discuss how the effectiveness of this teaching plan can be assessed.

5. Evaluation of the Teaching Plan

The effectiveness of a teaching plan can be assessed in a number of ways. This could entail qualitative, quantitative, formal, and informal mechanisms within both performance tasks and learning events. We develop a comprehensive teaching plan evaluation template following McAlpine and Harris [25]. Our template demonstrates that such evaluation requires identifying the key stakeholders, potential uses, methods/sources, criteria, and required resources/skills/timeframe, as described below.

5.1. Stakeholders of Evaluation

The stakeholders associated with our evaluation of the teaching plan are those individuals or institutions that have a vested interest in the subject and curriculum design since both the process and the outcome of any learning and teaching design will have a direct or indirect impact on them [26]. The most important stakeholders include:

- Students: Students are central to the process of curriculum design and are the most important category of stakeholder, as they will be directly affected by the quality, alignment, and authenticity of any learning design. Students’ involvement in the design evaluation can be seen in terms of, for example, using their input as an important source of evidence.

- Educators: Educators play an instrumental role in the curriculum design process and are important stakeholders in the various stages of producing learning and teaching content. As the initiators of a design, educators rely on their expertise, knowledge, and skills; student learning needs; best practices; university strategies; and industry needs, among others, to design and develop relevant and authentic curriculums.

- Managers: This category includes stakeholders with managerial and leadership roles such as Head of Department, Line Manager, Course Coordinator/Convenor, and Subject Moderator. These stakeholders have different levels of interest in the unit and curriculum design evaluation depending on their specific role, and as a result may be directly or indirectly affected. For example, line managers are responsible for mentoring and monitoring academic staff performance and development, particularly during their probationary period.

Parents and businesses constitute other relevant and important stakeholders who might be involved in curriculum design activities in different ways and capacities. For example, while the role of parents is more prominent in early, primary, and secondary education [27], businesses play an instrumental role in the case of tertiary education. The latter become more conspicuous when the notion of ‘job-ready graduates’ starts to dominate the attention of both universities and businesses [28].

5.2. Potential Uses for the Evaluation

The evidence and data that will be collected for the teaching plan evaluation can be used for a number of other applications, such as continuous improvement, succession planning, probation and promotion, and academic publication. These are further discussed in terms of their formative and summative orientation.

5.3. Methods and Sources of Evaluation

Evaluation methods, whether in the form of examinations, appraisals, reviews, observations, ratings, or even peer critiques, are key to ensuring the effectiveness of learning and teaching [29]. The nature and diversity of evaluation methods may also enable students to better understand the way they learn from different styles, environments, and resources related to learning and teaching. Light and Cox [29] argue that evaluation needs to be well balanced and derived from complementary sources to ensure rigor, validity, and reliability.

Consequently, we propose a mixed evaluation methods design (see Table 4). This allows triangulation of methods (and data) to improve rigor in the research process [30]. Further validating the application of a mixed evaluation methods design is the fact that the teaching plan evaluation should also focus on ILOs, TLAs, and ATs. These components demand different evaluation methods to ensure the reliability and validity of measurement.

Table 4.

Mixed evaluation methods design.

As shown in Table 4, six different evaluation methods are chosen from a pool of evaluation methods proposed by Light and Cox [29] for the purpose of our teaching plan evaluation. The selection is based on how well the chosen methods can measure the components of evaluation. To reduce the impact of bias and measurement error, triangulation of method and data has been considered in the overall design. In this regard, a general questionnaire and documentary research [31] will be used to evaluate the ILOs as part of the teaching plan evaluation design. This combination ensures that the evaluation entails both primary (survey) and secondary (literature) data and takes the perspectives of various stakeholders as sources of data to produce a comprehensive understanding of the ILOs, including their wording and alignment with the course ILOs; general and specific skills; university strategy; and industry needs.

The approach for the selection of evaluation methods for TLAs has been based on the notion of “evaluation in action” ([29], p. 199), as this provides a better context to gauge students’ engagement with the activities. The sources of data will be both students and educator, as the educator will be focusing on students’ attention, non-attention, and expressions as well as their interpretation of how well certain activities have played out. To address the bias associated with educator-administered data collection, portfolios and reflective commentaries are proposed to elicit students’ experiences and reflections in relation to their engagement with the TLAs. In this regard, the Blackboard Learn (or any other learning management system) subject portfolio application can be used as an instrument for collecting qualitative data from students.

Lastly, with respect to the ATs, two complementary evaluation methods are proposed for courses, parts of courses, or projects: assessment and questionnaires. The former provides valuable data in terms of feedback and grades, which could be used by the educator to pinpoint gaps in the subject content or problems with student understanding of specific theories/concepts. This method reflects a proactive approach based on eliciting both students’ and educators’ insights on an assessment piece through surveys and marking rubrics in order to evaluate how well aligned they are with subject objectives and how well they can measure students’ progress towards achieving the relevant ILOs.

5.4. Criteria for Evaluation

Three criteria can be used to make judgments about the teaching plan evaluation: constructive alignment, student satisfaction, and professional relevance. ILOs drive the strategic direction of a subject in terms of its TLAs and ATs. Therefore, it is very important that ILOs are developed with careful attention to ensure that students will acquire the required knowledge and skills through completing a particular subject [6]. In this regard, constructive alignment is an important criterion to ensure a curriculum evaluation design has a sound and rigorous theoretical and structural basis. As students are the most important stakeholder and the end consumer, it is crucial to use student satisfaction as a criterion for the judgment of a curriculum evaluation design. Ultimately, any subject design must suit students’ learning needs and wants, and appreciate the diversity that they bring into the learning environment. The last criterion (i.e., professional relevance) is also significant in making judgments on how well a teaching plan prepares students for the relevant industry and profession, that is, its authenticity for the ultimate goal of developing work-ready graduates.

For further clarification, a practical application of constructive alignment as a criterion to judge the existing ILOs of the logistics management subject is demonstrated in Appendix A.

5.5. Required Resources/Skills and Timeline for Implementation

Following Webb, Smith, and Worsfold [32], we have outlined the resources and skills needed to carry out our teaching plan evaluation which can be seen in Appendix B.

6. Conclusions

In this essay, our central aim was to assist logistics educators with designing student-centered, constructively aligned teaching plans that allow them to create authentic learning and teaching experiences for students. As such, we developed a conceptual framework based on the PDCA cycle, that integrates learning theory, learning model, student diversity, and educator knowledge/skills as core components of curriculum design. We applied and elaborated our framework by designing a teaching plan for the undergraduate logistics management subject. We also proposed a template which can be adopted by educators to evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching plans.

We believe that our essay contributes to advancing logistics education by providing a theoretically grounded teaching plan, accompanied by guidelines that can be used for its evaluation, to enhance students’ leaning experience and support them in achieving ILOs. Our frameworks and templates can be used beyond the logistics learning and teaching community, as they can be easily replicated in other disciplines. To our knowledge, we offer one of the first theoretically aligned and practically relevant discussions on curriculum design in logistics management which can be adopted by, for example, junior faculty working on their very first subject design project.

However, our work draws on conceptual development and anecdotal evidence lacking empirical validation. We hope that future research addresses this shortcoming, although we believe that our essay provides a solid foundation for future empirical studies on student-centered curriculum design and evaluation.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Practical Application of Constructive Alignment as a Criterion for Evaluating ILOs

The evaluation of ILOs can be undertaken by referring to the key elements that inform their construction and development. These elements are suggested to be associated with the paradigms (type of knowledge: declarative or functioning), principles (outcome verb, content, and context), and processes (taxonomies Such as Bloom’s [24] taxonomy (later revised by Anderson et al. [33]) and general guidelines) used in creating an ILO ([5,6,34]. We use the above-mentioned elements (labeled as horizontal evaluation) as well as the course intended learning outcomes (CILOs; labeled as vertical evaluation) as the basis for a critical evaluation of the existing ILOs of the Logistics Management unit. A quantitative mechanism based on a three-point Likert scale (where 1 = weak, 2 = average, 3 = strong) is used to facilitate evaluation of the subjective, qualitative discussions and evidence.

As per Table 4, the method of evaluation for the following practical application is documentary research, the instrument for evaluation is online database search, the data source is literature, the data type is qualitative, and fit envelopes are used for data transformation.

ILO1: Develop and articulate a coherent and cost-effective logistics plan for a complex business operation.

Vertical evaluation:

ILO1 contributes to four out of seven CILOs and four out of seven GILOs (generic intended learning outcomes) of the bachelor’s degree [6]. Therefore, the state of contribution of ILO1 to CILOs and GILOs (as recommended by AQF) can be classified as satisfactory. It is assumed that if an ILO contributes to at least three CILOs and three GILOs, it can be considered as ‘satisfactory’, complying with AQF requirements of the course. ‘Progressing’ and ‘unsatisfactory’ are the two other classifications, which represent a contribution of the ILO to fewer than three CILOs or fewer than three GILOs, and fewer than three CILOs and fewer than three GILOs, respectively.

Horizontal evaluation:

ILO1 is well written and clear in terms of the changes it intends to bring to the student’s learning process. The outcome verbs (i.e., develop, articulate) are well aligned with the nature of the unit (year three, outcome unit) and transferable in terms of developing appropriate TLAs and measurable ATs. Further, ILO1 clearly identifies the content (i.e., coherent and cost-effective logistics plan) that the verb is meant to address and the context (i.e., for a complex business operation) in which this content will be deployed [5].

ILO2: Articulate the reasoning behind logistics decisions, giving a balanced justification for the basis of decisions.

Vertical evaluation:

ILO2 contributes to two out of seven CILOs and three out of seven GILOs of the bachelor’s degree [6]. Therefore, the state of contribution of ILO2 to CILOs and GILOs (as recommended by AQF) can be classified as progressing.

Horizontal evaluation:

ILO2, while clear in terms of the change it aims to bring into the student’s learning process, suffers from lack of specificity of the context (i.e., giving a balanced justification for the basis of decisions) of the learning activity. The outcome variable (i.e., articulate) is relatively well aligned with the nature of the unit (year three, outcome unit) and transferable in terms of developing appropriate TLAs and measurable ATs. Further, ILO2 clearly identifies the content (i.e., the reasoning behind logistics decisions) that the verb is meant to address; however, as noted, the context in which this content should be deployed requires some modifications to ensure the TLAs and ATs can successfully deliver this ILO [5].

Appendix B. Resources/Skills and Timeline for Implementation of Teaching Plan Evaluation

| Stage | Description | Resources/Skills Required | Timeline |

| Identify the subject of evaluation | Possible options are subject matter expertise, design skills, delivery skills, management skills, mentoring students |

| To be determined |

| Define the components of evaluation | Identify the components of the subject that can be evaluated |

| To be determined |

| Select evaluation methods | Define the alternative evaluation methods that can be used to collect data on components of evaluation |

| To be determined |

| Locate information about the components of evaluation | Analyze options for instrument and sources for data |

| To be determined |

| Select resources to address the components of evaluation | Finalize decision on instruments and data sources and commencing data collection |

| To be determined |

| Undertake analysis of the data related to the components of evaluation | Clean and analyze various types of data collected through different instruments |

| To be determined |

| Write up the evaluation results | Interpret the results and develop a report that discusses the evaluation findings and recommendations |

| To be determined |

| Implement the final recommendation | Incorporate the evaluation results and recommendations into redesign of the components of evaluation and ultimately improvements in the subject of evaluation |

| To be determined |

| Source: Adapted from Webb et al. [32]. | |||

References

- Wiggins, G.; McTighe, J. Understanding by Design, 2nd ed.; ASCD: Alexandria, Egypt, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, S. Planning a Unit of Work: A Sequence of Letters. In Teaching: Making a Difference; Churchill, R., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Milton, Australia, 2013; pp. 210–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hannafin, M.J.; Hill, J.R.; Land, S.M.; Lee, E. Student-centered, open learning environments: Research, theory, and practice. In Handbook of Research on Educational Com-Munications and Technology; Spector, M., Merrill, M.D., van Merrienboer, J., Driscoll, M.P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.B. Constructive Alignment in University Teaching. HERDSA Rev. High. Educ. 2014, 1, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.B.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, M. Resources to Support the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) Compliance; Swinburne University of Technology: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, L.; Lima, R. Changes in teaching and learning practice in an undergraduate logistics and transportation course using problem-based learning. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.E.; Glick, B.J. Teaching Diversity: A Study of Organizational Needs and Diversity Curriculum in Higher Education. J. Manag. Educ. 2000, 24, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.B.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning; McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated: Berkshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harasim, L.M. Learning Theory and Online Technology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K.C.; Kalina, C.J. Cognitive and Social Constructivism: Developing Tools for an Effective Classroom. Education 2009, 130, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age”. 2005. Available online: http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Wilson, B.G. Thoughts on Theory in Educational Technology. Educ. Technol. 1997, 37, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy; Association Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Owlia, M.S.; Aspinwall, E.M. TQM in higher education—A review. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1997, 14, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Thought and Language; original work published in 1934; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, R.W. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Taba, H. Curriculum Development: Theory and Practice; Harcourt, Brace & World: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.F. A naturalistic model for curriculum development. Sch. Rev. 1971, 80, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. What Students Bring to Learning. Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Taking Student Retention Seriously: Rethinking the First Year of University. Keynote delivered at the FYE Curriculum Design Symposium; Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Kelvin Grove Campus: Brisbane, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Caffarella, R.S.; Baumgartner, L.M. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathworld, D.R.; David, M. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals; David McKay Company: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, L.; Harris, R. Evaluating Teaching Effectiveness and Teaching Improvement: A Language for Institutional Policies and Academic Development Practices. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2002, 7, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Developing Stakeholder Theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catsambis, S. Expanding Knowledge of Parental Involvement in Children’s Secondary Education: Connections with High School Seniors’ Academic Success. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2001, 5, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Chapman, E. Non-Technical Skill Gaps in Australian Business Graduates. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, G.; Cox, R. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: The Reflective Professional; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, R.; Naslund, D.; Bolumole, Y. The ‘White Space’ of Logistics Research: A Look at the Role of Methods Usage. J. Bus. Logist. 2005, 26, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, J. Evidence and Proof in Documentary Research: 1. Sociol. Rev. 1981, 29, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, F.; Smith, C.; Worsfold, K. Research Skills Toolkit; Griffith Institute for Higher Education: Queensland, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R.; Airasian, P.W.; Cruickshank, K.A.; Mayer, R.E.; Pintrich, P.R.; Wittroc, M.C. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Abridged, Ed.; Longman: White Plains, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cordiner, M. Learning Outcomes (Version 9)—An Introduction; University of Tasmania: Tasmania, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).