Abstract

Background: The logistics industry has seen the emergence of many startups in recent years. Many of these logistics startups use new technologies to develop disruptive products, services or platforms that are based on software. This paper presents the results of a Delphi study and a survey that were consolidated in a framework. The purpose is to understand the benefits that logistics startups derive from using agile methods, the difficulties they face in using these methods and the evolution of logistics startups in terms of using agile methods. Methods: A Delphi study with 29 experts and a global survey with 95 participants was conducted to look at the implementation of agile methods. The largest group of participants were members of (top) management, agile coaches and team leaders. Results: The framework consolidates gathered data to demonstrate how logistics startups apply agile methods and practices based on the results of the Delphi study and the survey, and how the usage of agile methods changes over the age of logistics startups. The results indicate that younger logistics startups use agile methods predominantly to design product features and maximise customer value, whereas logistics startups older than five years focus more on the optimisation of internal processes. Conclusions: The value of the present study lies in its contribution to the hitherto hardly examined research field of agility in logistics startups and the notable views of the experienced participants.

1. Introduction

Digitalisation raises the demand for software products such as platforms and (mobile) applications, also in industries that have not (primarily) earned money with software products in the traditional way. The logistics industry is one of these industries. The conducted Delphi study and survey explore how the logistics industry deals with the increasing need for software products. The studies explore how logistics startups use agile methods originating from software development to digitalise their services and products.

The rising number of disruptive logistics startups threatens larger, long-established logistics companies. Digitalisation is enabling the adoption of new technologies, data analytics and more automation. Platforms and “Uber-inspired” business models are being created as the idea of sharing becomes more widespread in the logistics industry [1,2,3]. Logistics startups benefit more easily from these new technologies [4]. It is easier for startups to use digital technologies to address inefficiencies such as long waiting and transport times, and to reduce costs through the use of assistive technologies such as sensor technology [5]. No longer is money made from the pure transport, handling and storage of goods, but also from a more information-oriented approach [6]. Information technology is becoming a decisive competitive factor, as it enables speed, flexibility and transparency of logistics processes [7,8,9].

As of the 1980s, the idea of agility itself has evolved from a concept concentrating on flexibility and leanness to a value-based concept [10]. Agility entails not only customer value, but also individuals, collaboration and interaction to achieve flexibility and leanness [10], and depends strongly on the mindset of all employees [11]. Still today, the concept of agility is a complex one and is interpreted in different ways in research and practice [10].

In recent years, the use of agile methods and practices (AMPs) has become increasingly popular and not only among software companies [12]. AMPs such as Scrum and Kanban as a tool for software development are used to manage increasing product development and project complexity, evolving customer requirements, insecurities in the business model, complex technological choices or other changing external influences, for example, in a company’s suppliers [13,14]. AMPs offer the promise of delivering business value in a timely and short iteration. This is facilitated by an incremental and empirical approach [15,16].

The aim of this framework is to describe AMPs used in logistics startups based on the results of a Delphi study and a survey. The purpose is to understand the benefits that logistics startups derive from using agile methods, the difficulties they face in using these methods and the evolution of logistics startups in terms of using AMPs.

The following research questions (RQ) are answered:

- RQ1: Which AMPs do logistics startups use?

- RQ2: How do logistics startups benefit from the use of AMPs?

- RQ3: What challenges do logistics startups face concerning the adoption of AMPs?

Practitioners, especially in logistics startups, as well as researchers, will benefit from the study. Employees from logistics startups can use the results to compare themselves with other startups and to see how agile methods are applied at older startups and prepare themselves for this. For researchers, the study contributes to closing the research gap identified during an extensive literature review [17].

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a brief outline of the fundamental definitions of logistics startups and agile methods. Section 3 presents the applied research designs and describes how the data gathered were used to develop the framework. Section 4 summarises the findings. Section 5 discusses the application of the framework, compares it to other frameworks and illustrates the limitations. Finally, Section 6 concludes this study.

2. Research Background

In this section, the concept of logistics startups and their attributes are presented based on the existing literature in order to create a common understanding of the framework and outcomes. The following subsection explains the concept of agile methods and how they can be associated with logistics startups.

2.1. Defining Logistics Startups

To comprehend the relevance of the concept of agility for logistics startups, it is necessary to understand what distinguishes startups from other company types. One of the best-known entrepreneurship educators, Steve Blank, and his co-author Bob Dorf, an accomplished startup trainer and consultant, define a startup as follows:

“A startup is not a smaller version of a large company. A startup is a temporary organisation in search of a scalable, repeatable, profitable business model.” [18], (p. XXI).

This definition can be expanded to include other aspects that can be identified in the entrepreneurial literature. A large number of sources agree with the following aspects. On the basis of their definitions, a startup can be understood as:

- A newly established company in its first phase of business operations, which is to set up a new product or service [19,20,21].

- A company that provides a solution to a problem whose solution is not yet known or obvious [22,23,24]. Thus, the idea of the product or service is unique or uses highly innovative technologies and/or business models to be successful [22,25,26].

- A company that has to cope with the insecurity related to its business model on a weekly or monthly basis [20,27,28].

- A company that can achieve success rapidly [29,30].

- A company that is focused on growth [31] and seeks to build a scalable and profitable business model [18,23].

- A company that often is operating in very volatile markets [23,32].

- A company that is struggling with a shortage of resources [20,23].

Not all newly founded companies are startups. In the following, the definition used in this study is that startups are younger than ten years, need to be (highly) innovative in their technology and/or business model, and have or are aiming for meaningful growth in headcount and/or turnover [33].

Startups can be founded as venture capital financed small businesses, but also as non-profit organisations and sometimes in collaboration with the government [27]. In the context of this study, a logistics startup is primarily concerned with the organisation and performance of transport, transshipment and storage of goods, but also with the optimisation of material flows and the complete, cross-company logistics management, i.e., supply chain management [34]. The supply of logistics services constitutes a derived demand and is therefore strongly dependent upon the primary demand development [35]. Logistics companies function as a link between the various stages of the value chain and the companies represented in it.

2.2. Defining Agile Methods

Since the 1980s, the concept of agility has grown from a concept of flexibility and leanness to a value-based concept [10,36]. Agility not only includes customer value, but also focuses on people, communication and collaboration to achieve flexibility and leanness [10]. Still today, the concept of agility is a multilayered one and is interpreted in a wide variety of ways in research and practice [10,37]. Conboy and Fitzgerald offer a definition of agility in more general terms, describing it as “the ability of an entity to proactively, reactively or inherently embrace change in a timely manner, through its internal components and its relationships with its environment” [38] (p. 39), [39,40,41,42]. They thereby characterise the core values of agile process models, above all openness to change and cooperation [43]. Qumer and Henderson-Sellers complement this definition with aspects of agility such as, “nimbleness, suppleness, alertness, responsiveness, swiftness and activeness” [44] (p. 122). Several other authors employ the attributes flexibility, speed, slimness, learning ability and sense of responsibility [38,45,46]. In this study, agility is seen as a concept that strives to reach flexibility, speed, leanness, learnability and responsiveness by being able to deal with change in a proactive, reactive or inherently fast way.

Agility is not limited to a specific functional area, but rather “can be addressed in different business competence areas” [47]. Agility’s origins in different areas are rooted in the shared objective of creating added value for the customer by offering the right product and being able to react to changes at short notice. Focus is put on the needs of the team working on the product as much as on the satisfaction of the customer.

In the year 2001, the so-called “Agile Manifesto” for software development projects was presented [11], following the development of agile and iterative process models such as the Rational Unified Process and methods such as Scrum and Extreme Programming (XP), Feature-Driven Development (FDD) and Kanban as tools for software development in the 1980s [13,48,49,50,51,52,53].

Based on four values and twelve principles, the Agile Manifesto aims to optimise the software development process and team collaboration. Since the focus is on developing customer value, many AMPs have been designed that can also be applied in other, non-IT-related areas [54,55]. The practices are linked to one method, but can also be used partly in combination with other methods (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The most popular agile methods together with related agile practices [13,51,53,63,70,71].

Using agile methods is especially appropriate for complex product developments or project situations that are characterised by quick and frequent changes [56,57]. Agile methods seek to decrease this complexity by accelerating the speed of response to change. Agile methods improve collaboration and promote trust between team members, as well as with the customers [58]. Furthermore, simpler processes, lower change costs and less time spent on changes lead to higher productivity and a lower defect rate [59,60,61]. This improves the product quality and lowers the complexity [62].

The most common agile methods are Scrum, Kanban and Scrumban [63]. The creators of Scrum, Schwaber and Sutherland describe Scrum as a framework for people to solve complex, adaptive problems while delivering creative products of the most value possible in a productive way [53]. By using an iterative approach with a mixture of sprints, synchronisation meetings (such as daily standups, sprint plannings and reviews) and retrospectives, various improvements are achieved by Scrum teams (see Table 1) [64].

Kanban as a tool for software development seeks to apply lean principles from manufacturing, such as eliminating waste, reinforcing learning processes and taking decisions as late as feasible. To visualise the status of current tasks with the help of a signboard is a core idea of the Kanban method. Moreover, the purpose of this visualisation of the work flow is to limit the work in progress. This implies that each person only works on a fixed maximum number of tasks in parallel. Kanban promotes continuous improvement to realise an efficient workflow [65,66]. Scrumban uses practices from Scrum and Kanban and makes it possible for teams to select the most suitable practices from both methods in agile teams [67].

The agile methods described above (Scrum, Kanban, Scrumban) were designed for organisations that consist of only one development team per software product. Agile methods for scaled teams, such as Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) and Large Scale Scrum (LeSS), were developed later. The term “Scaled teams” describes organisations in which several teams work together on one product and thereby increase the number of dependencies among the teams and the necessity for adapted AMPs [68,69].

3. Materials and Methods

The foundation of the framework is a Delphi study and a survey. In the following, the connection of the Delphi study and the survey is explained. First, an overview is given of how the two methods are linked. Then the procedures of the two methods are detailed. Finally, it is described how the data of the methods were used for the framework.

3.1. Overview of the Methods

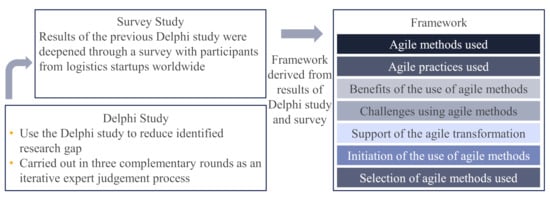

Two methods, a Delphi study and a survey, are used to answer the RQs from different perspectives. A Delphi study was conducted to collect the views of 29 experts in the hardly investigated field of research. Compared to the other expert assessment methods, Delphi has the advantage that it can be applied when the sample is too small to evaluate the validity of the outcomes using statistical methods [72]. Following the Delphi study and the evaluation of the results, the survey was prepared in order to deepen the results of the Delphi study. For this purpose, the questions from the questionnaire of the Delphi study were checked for their applicability within the survey, and further questions were generated. Due to the high number of answers from 95 survey participants who are employed in logistics startups, it was possible to derive a framework. The data of the Delphi study and the survey were analysed extensively, and a relationship between the age of the startups and the use of AMPs was found. Following these results, the startups were compared in their respective age groups in six dimensions. The development process of the framework is visualised below (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Development of the framework.

3.2. Related Work

To determine whether the Delphi approach and the survey are appropriate methods for data collection, related publications were analysed. Table 2 shows a selection of papers found.

Table 2.

Overview of Delphi studies and surveys in the field of agile methods [73,74,75,76].

These Delphi studies conducted in the areas of agile methods show that the Delphi approach can be used to gather the opinion of experts iteratively. Benefits such as anonymity, controlled feedback between the rounds and the use of learning from the previous rounds are the reasons the Delphi approach has been chosen. The surveys described above show that surveys are an appropriate method to collect views on the use of agile methods. Benefits such as anonymity, the gathering of different perspectives and the possibility of combining qualitative with quantitative questions are some of the reasons surveys are used. Validity can be increased by functionalities in the online survey tools, for example, by setting mandatory fields. Additionally, online survey tools support the focus on relevant questions as tools allow the use of automatic filters to hide questions or answer options that are irrelevant for the participants.

3.3. Procedure of the Delphi Study

To shrink the research gap, the Delphi study gathers the views of experts. In April 2020, three complementary rounds were executed to gain extensive insight into the views of 29 German panel members, who are experts in the fields of agility and logistics and mostly work as top managers, project leads or agile coaches in established logistics startups and established logistics companies [77]. The participants were interviewed on their usage of agile methods, the benefits they can realise through the use of agile methods and the challenges they face.

Originally, the Delphi method was applied to reach a consensus within a group of experts. Different metrics such as Fleiss’ Kappa [78] or Kendall’s concordance coefficient [79] are used for this objective. However, recent studies reveal that even the concept of “consensus” is ambiguous [80]. The objective of this Delphi study is not to achieve consensus, but to obtain valuable insights into the current use of agile methods and practices and to reduce the identified research gap [81]. For this aim, a questionnaire is adjusted between rounds to retrieve answers to the RQ. Therefore, the Delphi approach is called “modified” [80,82,83] and is used to perform an iterative expert assessment process [84] to evaluate the application of agile methods and practices in established logistics companies and logistics startups. In-depth insights can be gathered through qualitative, controlled feedback loops [82,85], which can be re-examined and assessed without bias in the following rounds with the help of quantitative questions. Three complementary rounds are conducted to gain a comprehensive insight into the views of the panel members who are experts in the field of agility and logistics. The results of the previous rounds are analysed, summarised and shared with the experts to sharpen the experts’ opinions [86]. The strong involvement of a team of experts who work in the area of IT in established logistics companies and logistics startups and who have in-depth experience with the use of agile methods guarantees that the results of the Delphi study are in line with reality. The Delphi study is at no time intended to conduct statistical data gathering. On the contrary, the aim is to gain a first impression of the hitherto unexplored research area through qualitative data collection and to reduce the identified research gap [17,87]. To this end, the perspectives of the participants are collected over three rounds. Through the iterative approach, answers can be deepened and unexpected perspectives can be responded to. The Delphi study was conducted according to the example of other modified Delphi studies [74,82,88].

3.3.1. Design of the Delphi Study

Three consecutive rounds of the study were performed. A questionnaire was prepared in each round and refined in five pre-tests with academic and industry experts. Subsequently, with an invitation and a link to the online questionnaire, an email was sent to the participating experts. The results of the earlier rounds were used to create the ensuing questionnaires. Participants had two weeks to complete the questionnaire. After the three rounds, the overall results were then analysed with two other researchers. The study was carried out with questionnaires in German and English. These were tested for consistency in advance.

For all rounds of the Delphi study, Google Forms was used. Overall, qualitative questions and quantitative questions with 7-point Likert items were applied. To avoid interpolation, it has proven to be the best choice [89]. A 5-point Likert item was applied in some cases to decrease complexity for the experts in the number of possible answers [90]. In addition, the quality criteria that are proposed by Diamond et al. were considered to guarantee the quality of this study [80]. At the end of each round, a report was sent to the experts with the results of the previous round. The experts had the opportunity to interact and discuss the results in an online forum and to give direct feedback to the researchers.

3.3.2. Selection of the Experts

It was expected that the participants in the Delphi study have in-depth knowledge about the use of AMPs in the IT departments of established logistics companies and logistics startups [91]. Given that expertise is challenging to evaluate, a systematic classification was performed [92,93]. Participants were chosen based on their expertise in the field of logistics and, in particular, their experience with AMPs. In the first round, 37 experts who work in established German logistics companies and German logistics startups were asked to participate. These 37 experts were acquainted with the researcher in various ways. Some participants of the logistics startups were already involved in previous studies. Other acquaintances were made at conferences or on previous project assignments. A total of 29 experts from 29 different companies with headquarters in Germany took part in the study. In the second round, 24 experts completed the questionnaire, and in the third round, 22 questionnaires were finished. A minimum number of 10–15 panelists is recommended in the literature for reliable results [84,94].

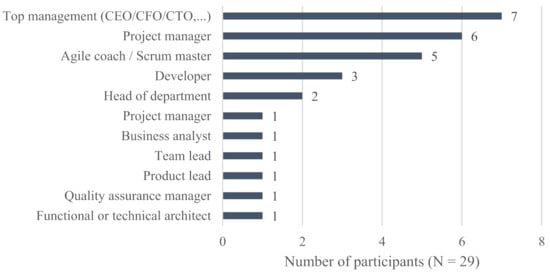

The experts who took part in the Delphi study are all professionals who are presently working on projects in logistics companies in the areas of logistics or agile IT consulting, most of whom have many years of professional experience. Most of the participants were members of top management, project managers, agile coaches and Scrum Masters. Participants also work as department heads, software developers, product leads and business analysts. Since a wide range of experts participated, a number of different perspectives can be included [91]. In Figure 2, the distribution of different roles of the participants of the first round can be seen.

Figure 2.

Roles of the experts of the Delphi study in their organisations.

For the Delphi study, participants are expected to demonstrate in-depth expert knowledge of the use of agile methods and practices in the IT departments of traditional logistics companies and logistics startups [91]. Expertise is difficult to assess, so a systematic classification was performed [92,93].

The experts were asked to self-assess their prior experience with agile methods. Of the 29 experts, 20 experts (almost 70%), rated their prior knowledge as five or higher on a scale of one to seven (see Table 3). A total of 16 of the 29 participants reported three or more years of experience with the application of AMPs.

Table 3.

Expertise of experts of the Delphi study in agile methods evaluated by themselves.

The anonymous conduct of the Delphi study removes the accountability of the participants’ statements. Therefore, the type of employing company of the experts (established logistics company; logistics startup) of the other panel members was known. This is necessary to prevent the experts from feeling they can say anything [93].

About 45% of the companies were founded in the past 10 years and can therefore be categorised as startups. A total of 14 of the 29 participants are from established logistics companies. Over 25% of all participating companies were founded in the past three years.

3.3.3. Analysis of the Data of the Delphi Study

The data gathered were analysed in detail between each of the three rounds and after the completion of the entire study. The answers to the individual questions were evaluated and considered from different perspectives. Cross-case analyses were also carried out, for example, comparing the answers of participants with specific roles or divided into startups and established companies [77].

3.4. Procedure of the Survey

After the evaluation of initial findings in the Delphi study, the next step is to test whether the initial results also hold up to the assessments of a broader set of participants. Following the Delphi study and the evaluation of its results, the survey study was prepared. For this purpose, the questions from the questionnaire of the Delphi study were checked for their applicability within the survey, and further questions were generated. The questionnaire was sent to the potential participants in October 2020.

3.4.1. Design of the Survey

The survey design focused on a descriptive analysis. The aim of the study was to gather the views of employees from logistics startups worldwide on their use of agile methods [95]. The participants had four weeks to complete the questionnaire. A reminder was sent to the study participants two weeks before the deadline ended as suggested by Rea and Parker [96]. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. In total, it included 12 multiple-choice questions and eight 7-point Likert questions. The first part focused on the organisational data of the participants such as company size and age, roles of the participants and their expertise regarding the use of AMPs. The second part inquired which AMP was used, the expected benefits and challenges faced using agile methods and the impact of the use of agile methods on the success of the logistics startups. The questionnaire was pretested with focus on content validity and readability: Two academic experts as well as two practitioners from logistics startups supplied feedback to improve the survey, which was incorporated into the survey.

3.4.2. Sample Size

Potential survey participants work in logistics startups around the world. The researcher identified potential participants on databases such as Crunchbase but also on an e-mailing list from the “Logistik-Initiative Hamburg”. If the e-mail addresses of the identified participants could not be found they were assumed based on the following set phrase: forename.surname@startupname.com. Forename and surname found were inserted into the set phrase together with the name of the logistics startup. Overall, the four-page questionnaire was sent to 4176 potential participants via e-mail. E-mail services returned 2183 e-mails that could not be delivered. Afterwards, a reminder was sent to those who did not answer and to those who started to fill out the questionnaire but did not complete it. In total, 95 participants completed the full questionnaire and provided usable responses; 228 participants started to fill out the questionnaire but did not complete it.

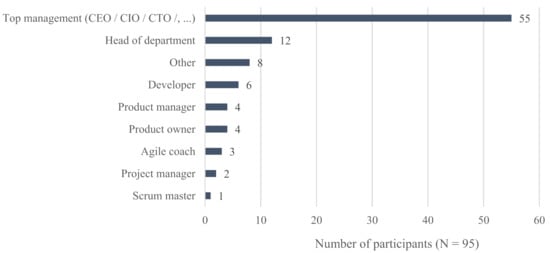

In the survey, mainly members of top management, department heads, product managers and product owners took part. Participants who selected “Other” work as business process managers, heads of agile mastery, account managers, strategy managers or data scientists. Experts performing different roles in the logistics startup participated in the survey. Through these different roles, a multitude of different views could be included [97]. In Figure 3, the breakdown of different roles can be seen.

Figure 3.

Roles of the survey participants.

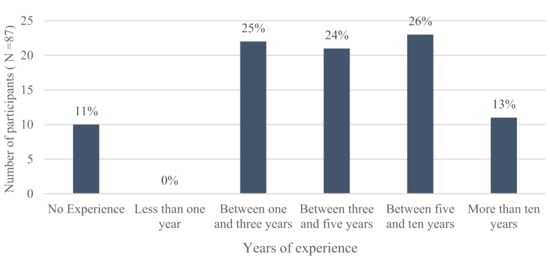

To assess the experience of the participants with the usage of agile methods, the participants were asked how long they have used agile methods. Answers of 87 participants were collected (see Figure 4). More than half of the participants had more than three years of experience with the usage of AMPs.

Figure 4.

Years of experience of the survey participants with the use of agile methods.

3.4.3. Analysis of the Data of the Survey

In the analysis of the data, results were broken down into clusters based on the age of the startups or they were evaluated without further clustering. There were some differences in the application of agile methods in startups of different ages. Additionally, to ensure completeness, other possible categories were also looked at to find out whether a different classification could also be interesting. Other categories tested were country of origin of the startups, number of employees, whether the startup is asset-based or asset-light, role of the participant, roles of the initiators and selectors of the agile methods. No significant differences could be found in clustering the data into other categories. To determine the significance, chi-square tests with p = 0.05 were applied [98].

3.5. Analysis and Consolidation of the Results of the Methods

The results of the Delphi study and the survey were compared with each other. Numerous similarities were found. In particular, it became clear that older startups, which have been existing for more than five years, sometimes even show similarities to the answers given by the participants of the established logistics companies in the Delphi study. It also became apparent that the responses of older logistics startups from the Delphi study and the survey were alike, just as the answers of younger startups were. After comparing the data, the visual framework was built. The framework lists the answers that were mentioned most frequently in both the Delphi study and the survey. Due to the high number of answers from participants who are employed in logistics startups, it was possible to derive a framework. The data of the studies were analysed extensively, and a relationship between the age of the startups and the usage of agile methods was found. Based on this, the startups were compared in their respective age groups in six dimensions. It is important to note that the age groups do not represent a strict division based on age, but rather gradual transitions between the different ages of the startups.

4. Results

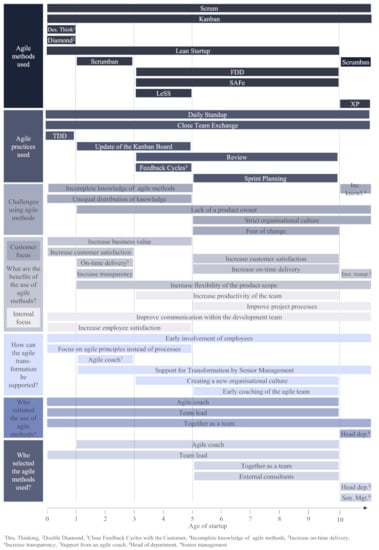

To summarise the results of the Delphi study and the survey, a descriptive framework was created (see Figure 5). The framework consists of one diagram that shows the age of the logistics startups on the horizontal axis. On the vertical axis, the following six different dimensions can be seen:

Figure 5.

Framework on the use of agile methods and practices and the realised benefits and challenges in logistics startups.

- AMPs used.

- Challenges faced introducing and using agile methods.

- Benefits of agile methods.

- Support measures when introducing agile methods.

- Initiator of the use of agile methods.

- Selector of agile methods.

These six dimensions were developed based on the RQ. For the six dimensions, answers that were given most often in the Delphi study and the survey are shown. For the logistics startups of different ages, it is described which AMP they use, which benefits they want to achieve using agile methods, which challenges the logistics startups face when using agile methods and who decided that agile methods should be used. The framework presents who selected the agile methods and what can be done to facilitate the introduction of agile methods. The six dimensions allow a comparison of the usage of AMPs over time in logistics startups. In the sense of contingency theory, there are additional explanatory organisational and environmental variables, besides the age of the logistics startups, that may have influenced the situation of the participants and their selection of AMPs [99,100]. An age limit such as five years is not a sharp limit but rather presents a smooth transition.

4.1. Agile Methods Used

In the first years of the startup life-cycle, logistics startups tend to use agile methods such as Design Thinking and Lean Startup that focus on product development. As the startups become older, the framework shows that logistics startups use more various agile methods. Mostly Scrum and Kanban are used.

4.2. Agile Practices Used

As Scrum is the most used agile method over all life-cycle stages in the logistics startups, a closer look was taken at the agile practices applied. In all startups, independent of the age of the startups, Daily Standups are used most often. Daily Standups are a common agile practice to facilitate the exchange within the (development) team. Besides the Daily Standups, logistics startups of all life-cycle stages prioritise a close exchange within the team in general. As the logistics startups become older, agile practices, such as a Kanban board for the visualisation of current and upcoming tasks and Sprint Planning meetings, are used to organise and plan the next tasks of the development team. Organisational meetings such as Sprint Plannings and Reviews that aim to structure the software development process are especially used in logistics startups older than five years. In the survey, participants from logistics startups older than five years state that they use AMPs to increase productivity and streamline processes. The results of the Delphi study influence the creation of the framework as well. The participants of the Delphi study who work in startups that are older than five years indicate that they use agile methods to increase productivity. Younger startups tend to focus more on collecting customer feedback and rapid product delivery.

Participants from the Delphi study state in many cases that they do not have the time to search for the most fitting agile approach and that they start working in a way that makes the most sense to them. The employees of these startups do not follow a dedicated approach but often find out later that the way they work in their startup resembles a specific agile method. A quote from one participant of the Delphi study, translated from German into English, is as follows: “Often the way of working results implicitly from what we consider useful rather than from a specific model that is implemented.”

4.3. Challenges Using Agile Methods

Whereas startups younger than five years struggle with an unequal distribution of knowledge within the team and/or incomplete knowledge about the use of agile methods, startups older than five years face challenges concerning the mindset of the employees. In startups older than five years employees tend to fear change. Projects are often embedded in a strict organisational structure. This results in an environment where it is more difficult to introduce new methods because employees might have a harder time to adapt to the new processes. A strict organisational structure often includes rigid hierarchies that first have to be dissolved officially and in the minds of the employees in order to enable self-organised teams that make decisions autonomously. Startups of nearly all ages face a challenge when the product owner is missing. One participant stated that that results in “too few requirements and incomplete information about the customer needs”.

4.4. Benefits Using Agile Methods

Two categories of reasons for the use of agile methods were identified. The darker fields present benefits of agile methods for the customer and the light blue fields describe the internal benefits for the startup itself and the development team. Younger startups concentrate especially on customer value. Over the life-cycle of the startups the focus moves to more internal, team-specific benefits. Startups younger than five years target the increase of customer value, customer satisfaction and the increase of flexibility of the product scope. For startups older than five years, internal benefits such as process optimisation are at least as important as customer-centered benefits.

For startups that are around three years old or older, a gap in external benefits is striking. Between three and five years old, the focus of the logistics startups is no longer on customer satisfaction and on-time delivery, but rather on the productivity of the teams. Older startups that are around five years old focus again on customer satisfaction and on-time delivery. This could be due to the fact that after the first successful launches of products, after about three years internal processes have to be optimised to allow for further growth and then later, at about five years, startups concentrate again on external benefits.

Overall, it needs to be said that all benefits, whether they improve the customer relationship or bring improvements within the organisation, are related. Benefits are also closely related to the challenges that occur. In the Delphi study, one participant described the following: “I think almost everything can be checked above, because there are so many dependencies. In our case it’s mostly the experience the team made in the past with non-agile methodologies that led to low quality of a product and essentially development of the product nobody actually needs. So, team spirit and employee satisfaction is also there, because with agile methodologies less things go to waste.” A challenge described by another participant was that “all customer communication must currently run through the CEO”. The framework shows that agile methods are used by startups of all ages to improve communication within the team. More direct communication streams between the development team and the customer may help to increase the level of customer satisfaction. A more direct communication with the customer supports, for example, the aim of one participant to “perform user research to understand and solve the customers problem 100% instead of taking many of the customers’ ideas as solutions”.

4.5. Support of the Agile Transformation

For startups of all ages, the early involvement of the employees is important to simplify the introduction of agile methods. For logistics startups up to the age of five years, employees focus on the agile principles instead of processes to support the introduction of agile methods. That means, for example, that teams focus on the collaboration within the team and apply only processes that are really needed. Startups often introduce agile methods straight from the beginning and do not transition, for example, from a classical approach to an agile approach, as it happens more often in established companies [76]. This may make it easier for startups to focus on agile principles rather than processes and their adaptation. For startups older than one year, the support of the senior management for the transformation is relevant. For startups older than three years, it is important to create a new organisational culture that includes self-organised teams and an open mindset for change of the employees. Interestingly, the fear of change among the employees increases simultaneously in logistics startups that are older than three years.

4.6. Initiation and Selection of Agile Methods

For logistics startups younger than ten years, the answers were quite homogenous. In most cases, the initiative for the use of agile methods comes from the team lead, the team itself or an agile coach.

The pattern of the people who selected the agile method that is to be applied is quite similar to the initiators. In younger startups the selection is made by the team itself, the team lead and/or the agile coach. As the startups become older, external consultants or roles higher up in the hierarchy, such as the head of department, are involved.

5. Discussion

In sum, based on the results of a Delphi study and a survey, a framework on the evolution of the usage of agile methods in logistics startups was developed. To discuss the framework, firstly its application is presented. Secondly, the developed framework is compared to existing frameworks on the evolution of startups. Thirdly, the impact and fourthly, limitations of the developed framework are discussed.

5.1. Application of the Framework

The descriptive framework is aimed at practitioners as well as researchers. Practitioners from logistics startups can use the framework for the following aspects:

- Compare their own startup to other logistics startups in terms of AMPs used. Practitioners can evaluate the reason and motivation of other startups for the application of agile methods and use this knowledge to improve their approach towards value creation for the customer and organisation of their internal processes.

- Gain an understanding of the challenges that other logistics startups face. Practitioners can gain knowledge on challenges that logistics startups of the same age but also older startups have to deal with. This can be helpful to prepare beforehand and solve challenges quickly or even prevent them.

Practitioners from established logistics companies can use the framework for the following aspects:

- Learn from the way logistics startups work and the usage of agile methods by logistics startups to improve in areas such as innovativeness where startups tend to be better than established companies.

- Compare their overall usage of agile methods to the approach of logistics startups and evaluate the differences of the usage using data from other companies of the same industry. Based on these differences, practitioners from established logistics companies can develop measures to improve their processes and realise the benefits of the application of agile methods.

For researchers, the presented framework can be of value due to the following aspects:

- Gather data in a hitherto hardly explored research field of agility in logistics companies and especially in logistics startups.

- Use the presented findings from logistics startups worldwide for further studies. Researchers could compare the data gathered with startups of other industries or take a deeper look at logistics startups from specific regions.

Both researchers and practitioners benefit from the following aspect:

- Improve processes in logistics companies and generate best practices that are valuable not only for logistics startups but also for established logistics companies that might face similar challenges, such as older, more mature logistics startups.

5.2. Comparison to Other Frameworks on the Evolution of Startups

In order to place the developed framework in the research context, it is compared below with other frameworks that describe the evolution of startups and the development of their needs as they become older. Related frameworks were searched through search engines such as ScienceDirect, SpringerLink and Google Scholar, applying the keywords “startup” and “framework”. Below, the studies published on agile methods used in startups that concentrate on startup evolution are presented. Those frameworks are used to validate the developed framework, as all frameworks focus on the development of startups and their needs over the time. The related publications use qualitative methods such as case studies and interviews but also analyse larger samples of more than 300 startups. No publication with a framework especially for logistics companies is identified. The next paragraphs summarise the most relevant publications (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Publications related to the framework developed.

In the following, the related framework and its corresponding publications are summarised. Afterwards, a comparison to the framework developed takes place.

Hwang and Ho Park (2006) assessed the evolutionary importance of alliances over the life-cycle of biotech startups. Over the life-cycle of the biotech startups, the startups that are analysed engage in different alliances. Many firms seem to create alliances directly at the so-called “birth stage of the organisational life cycle” [101] to reduce costs, especially in R&D activities. Startups in birth and growth stage engage in alliances with partners with a similar strategic scope to increase their knowledge in their specific niche. Mature startups seek to create alliances with partners with complementary resources to broaden their market share.

Giardino et al. (2014) analysed which factors influence the success of software startups. Even though it is advised to first understand the problem/solution fit of the product [106], startups often prioritise the product development to be able to launch a product as soon as possible. Neglecting customer feedback and a therefore missing problem/solution fit causes the failure of the startups examined within the study of Giardino et al. [102]. By analysing the results of the two startups, which coped with similar obstacles during their evolution, a framework was created by Giardino et al. The framework includes four stages. In the first stage, the problem/solution fit needs to be found. After increasing functionalities and improving the design in the second stage, the framework advises growth of the team in the third stage. In the last step, the framework prescribes the development of a strategic business model and a sales roadmap.

Sekliuckiene et al. (2018) demonstrated that at different life-cycle stages organisational learning processes vary in global startups. Additionally, the results from the literature review demonstrate that “learning processes of cyclical entrepreneurship learning” are necessary to move to the next life-cycle stage [103]. That means that employees from startups have to learn from the successes and failures they made during one life-cycle stage in order to move to the next one. Sekliuckiene et al. establish that as the startups mature, strategic planning, internal processes and scaling become relevant.

Gralha et al. (2018) detailed the development of requirements in software startups along six different dimensions: Requirements artefacts, knowledge management, requirements-related roles, planning, technical debt and product quality. The startups’ progress along these six dimensions mirrors the abilities of a startup to satisfy the customers’ needs, react to changing requirements more effectively, and to use resources effectively [104]. Even though the six dimensions are not fundamental to the startups success, they help the startup mature and grow.

Degl’innocenti (2019) described the history of organisational development in companies and the challenges companies face today. She evaluates if Service Design can improve the current understanding of organisational development. She summarises the main publications and creates a definition of organisational development [105]. In the first step of organisational development, it is necessary to understand the organisation’s values and maximise them. Afterwards, the company’s strategy is aligned so that the organisation’s success can be maximised. Thirdly, the focus moves to the employees and the optimisation of internal processes.

5.3. Classification of Frameworks in the Research Context

To sum up the overview of related frameworks, it can be said that no scientific framework that looked at the evolution of logistics startups was identified. Overall, the following scientific value can be observed:

Hwang and Park (2006) presented results on biotech startups, which seem to be more technology-focused than logistics startups. Biotech startups rely strongly on R&D activities and need alliances to increase their market share. Due to this, Hwang and Park concentrate their description of the evolution of biotech startups on alliances and do not consider the internal organisation and processes of startups, which are the focus of this publication. Nevertheless, the data of Hwang and Park display that younger startups concentrate on development of knowledge in their specific niche to enhance their product development. These results show similarities to the results of this publication described above, where it is shown that the focus of young startups is development of business value and the increase of customer satisfaction (see Figure 5). The results of the Delphi study and the survey show that younger startups focus strongly on the development of the right product and fast product delivery [77,98].

Giardino et al. (2014) characterised factors that can lead to the failure of software startups. Even though taking these factors into account may extend the life of startups, Giardino et al. do not explicitly define the evolution of a startup, which is the center of the framework of this publication. However, Giardino et al. describe that product development is one of the most important aspects of the first life-cycle. That matches the usage of agile methods in startups of the framework of this publication. In the Delphi study and the survey, participants stated that they mainly use agile methods to develop their products.

Sekliuckiene et al. (2018) explained the organisational learning over the life- cycle of startups. They underline the importance of cyclical learning and the use of iterations to learn from customer feedback. Sekliuckiene et al. do not focus on AMPs or the logistics industry. The framework developed by Sekliuckiene et al. shows similarities to the framework of this paper. In the framework of Sekliuckiene et al., product design is the objective of startups in their first life-cycle stage. That is consistent with the use of agile methods of startups surveyed for the framework of this paper. Sekliuckiene et al. explain that more mature startups move their focus to internal processes and strategies. This aligns with the participants of the survey as they focus more and more on the optimisation of internal processes and the introduction of agile scaling methods [98].

Gralha et al. (2018) detailed the handling of changing requirements in software startups. Even though they do not present any agile methods, the holistic approach of Gralha et al. is related to the framework presented, as agile methods are mostly used in software departments to deal with reoccurring changing requirements. Gralha’s publication is beneficial as it presents the relationship between different dimensions and underlines the importance to not only focus on the product, its design and the customer value, but also on the needs of the organisation. Similarly, as in the framework presented, Gralha et al. describe that startups need to be flexible in regard to their product development and implementation of customer requirements but also satisfy the needs of their employees in order to evolve.

Degl’innocenti (2019) described a general approach to organisational development of companies. Her approach does not deal explicitly with logistics startups. However, her thesis lays a valuable foundation for understanding organisational development in general and can also be used for logistics startups. For the framework presented, her description of organisational development proves to be very valuable. Degl’innocenti’s findings show similarities to the framework presented in this paper. Degl’innocenti expresses that companies first focus on the value created for their customers through their products. Equivalent to this, younger startups in the presented framework concentrate on the development of customer value. As startups become older, Degl’innocenti and the framework presented describe how they focus more on organisational structures.

The framework explained in this paper is based on the collection of qualitative, real-world data. It describes findings that are validated through other studies. However, no framework could be found that explicitly addresses logistics startups and their use of AMPs.

5.4. Impact of the Framework

An important benefit of the proposed framework is the focus on practitioners. Agile methods are people-centered and aim to maximise the benefit generated through products quickly. To become a value-driven logistics startup, it is necessary to continuously question all processes used and improve them with regard to the fast creation of customer value. The framework created supports this approach by enabling logistics companies to compare themselves to other logistics startups of different ages and life-cycle stages. In particular, a closer look on the agile practices used can be helpful for practitioners to understand more closely why the numerous participants of the logistics startups apply agile methods. Established logistics companies can learn from the way logistics startups work. Logistics startups have to cope with strong pressure to create innovative products and apply appropriate working methods such as agile methods. Digitalisation is increasing the pressure to innovate for some established logistics companies as well, which is why established logistics companies have to adapt their ways of working and introduce agile methods. The framework presented shows what motivates the participants to use agile methods (Benefits), what challenges they face, and how and by whom the use of agile methods can be supported. Additionally, practitioners can use this framework during retrospective meetings to widen the point of view of the development team for other possible benefits and challenges, as the aim of Retrospectives is to inspect and adapt the existing organisational environment. Practitioners could benefit from these results and learn why other companies are possibly faster in the development of new innovative products. The framework can be used by researchers to assess which AMPs are used by more established logistics companies and why these methods are selected. Researchers can use the framework to deepen the results through case studies, for example, in different kinds of logistics companies or in different cultural areas.

5.5. Limitations of the Framework

It can be argued that the use of a framework in the field of agile software development in the logistics industry might be too inflexible in its usage and/or increase the overall effort applying agile methods. However, this is why the framework focuses on areas that have a strong impact on the success of startups. Many participants of the Delphi study and the survey stated that startups have to be agile in order to be successful. For this reason, the framework aims to facilitate the usage of agile methods for logistics startups.

As the design of a framework determines the results derived for the practitioners and researchers, multiple discussions were carried out with researchers and company experts during the development of the framework. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that personal subjective ideas influenced the design of the framework. The framework is based on the results of a Delphi study and a survey that were conducted worldwide to gather different views from established logistics companies and logistics startups.

Another limitation is the high rate of nonresponse of the survey participants. A total of 4176 potential participants were contacted, and 2183 e-mails could not be delivered. This leaves 1993 e-mails that could be delivered. In total, only 95 (4.7%) completed the questionnaire and 228 (11.4%) only started to fill out the questionnaire. It needs to be assumed that the participants who completed the questionnaire have a positive attitude towards AMPs and that a non-response bias (NRB) exists. The NRB needs to be kept in mind when evaluating the results. It is possible that mainly participants with a favourable relation to agile methods took part in the survey and hence the opinions about agile methods are more positive than they are in reality

It needs to be noted that not only time and the age of startups influences the development of logistics startups related to the usage of AMPs. Other environmental and organisational variables possibly impact the selection and usage of AMPs.

Finally, for a more detailed investigation, case studies can be useful to deepen the current understanding. Additionally, the findings gathered in the framework that focus on logistics startups can be compared to the application of agile methods in more established logistics companies or other industries. It could also be interesting to look especially at older startups and compare them with established logistics companies to determine their differences and describe the transition from logistics startups to established logistics companies related to the use of AMPs.

6. Conclusions

Based on a Delphi study and a survey, a framework on the usage of agile methods in logistics startups was developed. The goal of this paper was to gather the results of the Delphi study and the survey. The framework shows which AMPs are used, which benefits logistics startups aim to realise through the usage of agile methods and what challenges they face. In summary, it can be seen that in young, newly founded startups, agile methods are mainly used to find the product idea and to generate added customer value. Older startups increasingly use agile methods to structure internal processes and have to deal with cultural difficulties within the organisation and fear of change among employees. Comparing the developed framework with existing literature shows that no similar framework exists that evaluates or structures the usage of agile methods in the logistics industry. However, other frameworks show similarities in regard to the evolution of logistics startups. The framework contributes to the work of practitioners in logistics startups as they can compare themselves with other logistics startups. Practitioners from established logistics companies can use the framework to understand how logistics startups work differently and how logistics startups cope with digitalisation. Researchers benefit from the framework as the frameworks starts to close the identified research gaps. Future research could involve case studies to explore how and what traditional logistics companies and logistics startups can learn from each other, particularly in terms of agile methods but also how they can profit from each other’s ways of approaching customer-value creation. The question could also be posed as to what degree the startups’ organizational culture is more compliant with the implementation of agile methods than that of traditional logistics companies, as organizational culture and anxiety about change are the main challenges for traditional logistics companies in regard to the introduction and use of agile methods and practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z.; methodology, M.Z.; validation, T.H. and A.K.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.H.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, T.H.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the West of Scotland (protocol code 9595, 13 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Results of the Delphi study can be found here: M. Zielske and T. Held, “Application of agile methods in traditional logistics companies and logistics startups”, J. Syst. Softw., vol. 177, no. 7, pp. 1–17, July 2021 Results of the survey are published here: M. Zielske, T. Held, and A. Kourouklis, “Application of agile methods in logistics startups—Results from a global Survey Study”, in Nofoma—Nordic Logistics Research Network, 2021, pp. 1–15.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hofmann, E.; Osterwalder, F. Third-Party Logistics Providers in the Digital Age: Towards a New Competitive Arena? Logistics 2017, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, A.-W. Theses on Digitalization. In The Drivers of Digital Transformation; Abolhassan, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Abideen, A.Z.; Pandiyan, V.; Sundram, K.; Pyeman, J.; Othman, A.K.; Sorooshian, S. Digital Twin Integrated Reinforced Learning in Supply Chain and Logistics. Logistics 2021, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, H.; Wehberg, G.; Zimmermann, P. Supply Chain Start-Ups Are Coming of Age; Deloitte Australia: Houston, TX, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, T. Technology Innovation Management Review Improvising Entrepreneurship. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2014, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.; Amaral, A.; Pereira, T. Industry 4.0 implications in logistics: An overview. In Proceedings of the Manufacturing Engineering Society International Conference, Vigo, Spain, 28–30 June 2017; Volume 13, pp. 1245–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E.; Rüsch, M. Industry 4.0 and the current status as well as future prospects on logistics. Comput. Ind. An. Int. J. 2017, 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, I.; Cebeci, H.I.; Ghorbani, S.; Renatačinčikait, R.R. An Integrated Approach for Evaluating Lean Innovation Practices in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain. Logistics 2021, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, T.; Ijuin, H.; Yamada, T.; Nagasawa, K.; Zhou, L. COVID-19 Disruption Strategy for Redesigning Global Supply Chain Network across TPP Countries. Logistics 2021, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conboy, K. Agility from first principles: Reconstructing the concept of agility in information systems development. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.; Beedle, M.; Bennekum, A.V.; Cockburn, A.; Cunningham, W.; Fowler, M.; Grenning, J.; Highsmith, J.; Hunt, A.; Jeffries, R.; et al. Agile Manifesto. 2001. Available online: https://agilemanifesto.org/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Laanti, M.; Salo, O.; Abrahamsson, P. Agile methods rapidly replacing traditional methods at Nokia: A survey of opinions on agile transformation. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2011, 53, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K. Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, A.; Highsmith, J. Agile Software Development: The People Factor. Comput. Sci. 2001, 34, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Gravell, A.M.; Wills, G.B. Historical Roots of Agile Methods: Where Did “Agile Thinking” Come From? In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing Book Series (LNBIP, Volume 9); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Larman, C.; Basili, V.R. Iterative and incremental developments. A brief history. Computer 2003, 36, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielske, M.; Held, T. An overview of the use of agile methods in logistics start-ups Results from a systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Academic Conferences—Transport, Logistics, Tourism and Sport Science, Budapest, Hungary, 12–13 March 2020; pp. 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, S.; Dorf, B. The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step-by-Step Guide for Building a Great Company; K & S Ranch, Inc.: Pescadero, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gaida, K. Gründen 2.0; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster, N.; Giardino, C.; Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Gorschek, T.; Abrahamsson, P. Software development in startup companies: A systematic mapping study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2014, 56, 1200–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, W.; Martins, R. Logistic Strategy and Organization in Brazilian Small and Medium-Sized Entreprises (SMEs); Vilniaus Universiteto Leidykla: Vilniaus, Lithuania, 2011; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Albats, E.; Fiegenbaum, I. Key Performance Indicators of Startups: External view. In Proceedings of the XXVII ISPIM Innovation Conference, Blending Tomorrow’s Innovation Vintage, Porto, Portugal, 19–22 June 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Abrahamsson, P.; Wang, X.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Shah, S.; Bajwa, S.; Baltes, G.H.; Kieran, C.; Cullina, E.; Dennehy, D.; et al. Software Startups—A Research Agenda. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2016, 10, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, S.; Wang, X.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Abrahamsson, P. “Failures” to be celebrated: An analysis of major pivots of software startups. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2017, 22, 2373–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, C.; Paternoster, N.; Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Gorschek, T.; Abrahamsson, P. Software Development in Startup Companies: The Greenfield Startup Model. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2016, 42, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Stöckmann, C. Filling the Entrepreneurial Orientation-Performance Gap: The Mediating Effects of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovations. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1001–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moogk, D.R. Minimum Viable Product and the Importance of Experimentation in Technology Startups. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, E. The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses; Crown Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville, R.; Ramesh, B.; Levine, L.; Pries-Heje, J.; Slaughter, S. Is internet-speed software development different? IEEE Softw. 2003, 20, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotins, E.; Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Gorschek, T. Software Engineering Knowledge Areas in Startup Companies: A Mapping Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Software Business, Braga, Portugal, 10–12 June 2015; pp. 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Wiklund, J. Conceptual and Empirical Challenges in the Study of Firm Growth. In Entrepreneurship and the Growth of Firms; Davidsson, P., Wiklund, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, N.; Kundisch, D. Much more than “same solution using a different technology”: Antecedents and consequences of technology pivots in software startups. In Proceedings of the Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik, Lüneburg, Germany, 6–9 March 2018; pp. 526–537. [Google Scholar]

- Ripsas, S.; Tröger, S. 3. Deutscher Startup Monitor. Bundesverb. Dtsch. Startups 2015, 3, 2–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpfert, I.; Seeßle, P. Startups in der Logistikdienstleisterbranche: Eine Systematisierung der Neuen Marktteilnehmer Sowie Analyse von deren Auswirkungen Auf Die Logistikdienstleisterbranche; Philipps-Universität Marburg: Marburg, Germany, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, A. 4PL-Providing TM Als Strategische Option für Kontraktlogistikdienstleister: Eine Konzeptionell-Empirische Betrachtung; Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag/GWV Fachverlage GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stavru, S. A critical examination of recent industrial surveys on agile method usage. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 94, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Wohlin, C.; Angelis, L. Investigating the applicability of Agility assessment surveys: A case study. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 98, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conboy, K.; Fitzgerald, B. Toward a Conceptual Framework of Agile Methods: A Study of Agility in Different Disciplines. In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM Workshop on Interdisciplinary Software Engineering Research, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 5 November 2004; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.; Sarker, S. Exploring agility in distributed information systems development teams: An interpretive study in an offshoring context. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsjørn, Y.; Sjøberg, D.I.K.; Dingsøyr, T.; Bergersen, G.R.; Dybå, T. Teamwork quality and project success in software development: A survey of agile development teams. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 122, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, M.; Wang, X. An investigation of agility issues in scrum teams using agility indicators. In Information Systems Development: Asian Experiences; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 449–459. [Google Scholar]

- Dikert, K.; Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C. Challenges and success factors for large-scale agile transformations: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 119, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M. Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Qumer, A.; Henderson-Sellers, B. Crystallization of agility: Back to basics. In Proceedings of the ICSOFT 2006—1st International Conference on Software and Data Technologies, Setúbal, Portugal, 11–14 September 2006; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.; Whitman, L. Attaining Agility At The Enterprise Level. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering, San Antonio, TX, USA, 17–20 November 1999; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, B.; Turner, R. Balancing Agility and Discipline: A Guide for the Perplexed, 1st ed.; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen, P. Adopting key lessons from agile manufacturing to agile software product development—A comparative study. Technovation 2009, 29, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Nonaka, I. The new new product development game: Stop running the relay race and take up rugby. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1986, 64, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber, K. Scrum Development Process. In Business Object Design and Implementation; Springer: Austin, TX, USA, 1997; pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kruchten, P. The Rational Unified Process; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S.R.; Felsing, J.M. A Practical Guide to Feature-Driven Development; Prentice Hall PTR: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D. Making the business case for agile management: Simplifying the complex system of software engineering. In Motorola S3 Symposium; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber, K. Agile Project Management with Scrum; Microsoft Press: Redmond, WA, USW, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith, J.A. Agile Project Management: Creating Innovative Products; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, S. Bridging the Gap: Traditional to Agile Project Management 1. PM World J. 2015, IV, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, C.F.; Snowden, D.J. The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM Syst. J. 2003, 42, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R.D.; Mowles, C. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics: The Challenge of Complexity to Ways of Thinking about Organisations, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaim, R.; Härting, R.C.; Reichstein, C. Benefits of agile project management in an environment of increasing complexity—A transaction cost analysis. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; Volume 143, pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V.; Nies, A. Agile with fragile large legacy applications. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—Agile 2008 Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4–8 August 2008; pp. 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, J.J.A.; Shah, A.; Sajjad, F. Evaluation of agile methods for quality assurance and quality control in ERP implementation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems, ICICIS 2017, Cairo, Egypt, 5–7 December 2017; pp. 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Prater, E.; Biehl, M.; Smith, M.A. International supply chain agility Tradeoffs between flexibility and uncertainty. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, F.; Aftab, S.; Waheed, U.; Muhammad, S.S. Agile Software Development Models TDD, FDD, DSDM, and Crystal Methods: A Survey. Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Eng. 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- VersionOne CollabNet. The 13th Annual State of Agile Report; Digital.ai: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2019; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, S.; Aftab, S. Latest Transformations in Scrum: A State of the Art Review. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2017, 9, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahmad, M.O.; Dennehy, D.; Conboy, K.; Oivo, M. Kanban in software engineering: A systematic mapping study. J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 137, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business; Blue Hole Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, M. Analyzing Agile Development-from Waterfall Style to Scrumban. Inform. Econ. 2016, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.; Paasivaara, M. Scaling Agile. IEEE Softw. 2017, 34, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larman, C.; Vodde, B. Large-Scale Scrum: More with Less; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, A. Surviving Object-Oriented Projects: A Manager’s Guide; Addison Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsson, P.; Warsta, J.; Siponen, M.T.; Ronkainen, J. New directions on agile methods: A comparative analysis. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Software Engineering, Portland, OR, USA, 3–10 May 2003; pp. 244–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. Expert Opinions in Forecasting: The Role of the Delphi Technique; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Conboy, K.; Fitzgerald, B. The views of experts on the current state of agile method tailoring. In IFIP International Federation for Information Processing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Volume 235, pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, E.M.; Winter, D.; Escalona, M.J.; Thomaschewski, J. Key challenges in agile requirements engineering. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 283, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pantiuchina, J.; Mondini, M.; Khanna, D.; Wang, X.; Abrahamsson, P. Are software startups applying agile practices? The state of the practice from a large survey. In Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- CollabNet VersionOne. The 15th Annual State of Agile Report; Digital.ai: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zielske, M.; Held, T. Application of agile methods in traditional logistics companies and logistics startups. J. Syst. Softw. 2021, 177, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P. Species associations: The Kendall coefficient of concordance revisited. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2005, 10, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N. An experimental study of group opinion: The Delphi method. Futures 1969, 1, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J.; Marchildon, G.P. Using the Delphi Method for Qualitative, Participatory Action Research in Health Leadership. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasarathy, L.; Turk, D. Drivers of agile software development use: Dialectic interplay between benefits and hindrances. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielske, M.; Held, T. Agile Methods and Practices Used by Logistic Start-Ups and Traditional Logistic Companies: Protocol of a Systematic Literature Review; Hamburg University of Applied Science: Hamburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gary, J.; Gnatzy, T.; Warth, J.; Von Der Gracht, H.; Darkow, I.-L. Validating an innovative real-time Delphi approach-A methodological comparison between real-time and conventio. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstad, K. Response Interpolation and Scale Sensitivity: Evidence Against 5-Point Scales. J. Usabil. Stud. 2010, 5, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, R.; Gullone, E. Why we should not use 5-point Likert scales: The case for subjective quality of life measurement. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Quality of Life in Cities, Singapore, 8–10 March 2000; pp. 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, M.J. Delphi: A technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision-making tasks in education. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackman, H. Delphi Critique: Expert Opinion, Forecasting and Group Process, 1st ed.; DC Heath: Lexington, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Lilja, K.K.; Laakso, K.; Palomäki, J. Using the Delphi method. In Proceedings of the Technology Management in the Energy Smart World, Portland, OR, USA, 31 July–4 August 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, 2nd ed.; Pinter Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rea, L.M.; Parker, R.A. Designing and Conducting Survey Research: A Comprehensive Guide, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, C.; Dobbie, A.E.; Parchman, M.; Tysinger, J. Guidelines for Constructing a Survey. Fam. Med. 2002, 34, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zielske, M.; Held, T.; Kourouklis, A. Application of agile methods in logistics startups—Results from a global Survey Study. In Nofoma—Nordic Logistics Research Network; University of Iceland: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Nobel, R.; Ridderstrale, J. Knowledge as a Contingency Variable: Do the Characteristics of Knowledge Predict Organization Structure? Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 223–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Stewart, T.I. A General Contingency Theory of Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]