1. Introduction

A new phenomenon of logistification of the world inspires management research, including studies on HR management in logistics. The aim of this article is to present the relationship between the design of the personnel function and the effectiveness of logistics management in a firm. The new trends in the twenty-first century world economy develop against the backdrop of all-embracing logistification, understood as a broad application of logistic processes in economic and non-economic activities, within and between countries [

1]. These new trends include a growing internationalization of companies, and accelerating international flows of capital, people, and knowledge, especially technical knowledge. Notably, knowledge transfer is increasingly associated with the personnel function [

2]. In this particular context, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) Logistification of the world implies a growing importance of the personnel function in logistics management.

A systematic way of verifying this hypothesis is to select and then characterize the key elements of a successful delivery of the personnel function in logistics management. The selection can best be made by posing the following two research questions:

This paper has two parts. The first, a theoretical section, reviews the literature of the last decade, exploring the place of HR management in logistics. In order to identify and classify modern-day challenges of HR management, this part of the article also presents the findings of statistical analysis of relevant data reported by leading consulting firms in the period 2010–2018.

The second, empirical part of this article presents the results of studies of 236 large, medium-sized and small Polish firms, completed in 2017–2018. To ensure representativeness of the sample, a stratified random sampling was used. The inductive-deductive model of research was used, and the research procedure was conducted by a diagnostic survey method. Subsequently, a statistical analysis of the results was made using the response-structure, correlation, and factor analyses, which finally led to the presentation of an original conceptual model of the personnel function in logistics management.

2. The Importance of Human Resource Management in Logistics. A Literature Review.

It is widely believed that a new currency has emerged in the economy of the twenty-first century; this currency is knowledge [

3]. For this reason, and because of misgivings about artificial intelligence, likely to supersede the human mind in the future, the highest focus must be on human resources. This is particularly pertinent to logistics, since all supply chain management projects require non-standard knowledge and exceptional imagination.

The literature review has to begin with a notion of logistification of the world [

1]. A phenomenon of logistification of different spheres of human endeavor was, after all, one of the reasons for writing this article. In the world that undergoes a continuous transformation of its economy, politics, and societies, logistics, with its systemic and complex processes, is omnipresent in manufacturing industries, the automotive industry, the military, sports and health sectors, or even the charitable sector. Therefore, logistification of the world, with its inter-organizational dynamics, has a profound impact on companies irrespective of their size, and commits to better management of logistic flows, networks, and systems. The ability to innovate in the area of logistics requires HR management excellence, and heavily relies on the quality of logistics managers’ knowledge and training.

The 1995–2020 literature on human resource management in logistics features two major discourse themes:

A growing internationalization of business organizations, supply chains in the global economy, and the flows of the factors of production: capital, workforce, and technologies.

A strong growth in the importance of management teams’ key competencies in companies’ logistics.

One of the first publications in which modern HR management was given a special role in logistics was the work published by the Global Logistics Research Team at Michigan State University [

4], reporting on the results of studies of 3693 American companies. The findings of those studies allowed not only to define the scope of world class logistics, but also characterized, in detail, logistics competencies, with a specific focus on designing the structure and techniques of managing human resources. In the literature, the concept of world class logistics is also referred to as international logistics [

5]. In publications, such as International Logistics [

6], or International Logistics and Supply Chain Outsourcing [

7], special attention is given both to the globalization of logistics, and the management of workforce flows in supply chains as part of strategic vision of logistics development. With the onset of the twenty-first century, attention turned to the nature of the relationship between global supply chains and the need for modern human resources management in supply chain member companies. Studying the relationship between HR management and supply chain operations has become an important new area of research [

8]. Fu, Flood, Bosak, Morris and O’Reagan [

9] consider human resources management a critical element of logistics operations in supply chains, particularly in achieving client satisfaction through service excellence. Empirical evidence suggests that a precise identification of HR management practices having the biggest impact on the effectiveness of supply chain management is key to company supply performance [

10]. In turn, Griffith [

11] argues that the human capital employed by the firm provides the firms’ capabilities to achieve and sustain its competitive position in the global supply chain. Harvey, Fisher, McPhail, and Moeller [

12] emphasize a demand for managers capable of managing inter-organizational relations in global supply chains, who are also sensitive to cultural differences. Hence Richey, Tokman, and Wheeler [

13] suggest that logistics managers must possess superior mental aptitude, outstanding interpersonal skills, and creative imagination.

Some commentators postulate that in addition to core operational competences, managers should have deep understanding of different business functions, as they share responsibility for the company’s financial performance. This “organizational awareness” [

14] is necessary for a company to sustain competitive advantage, and to systematically build trust with customers, which is so important for the company’s performance. Therefore, the management education and training programs within organizations need to change and include—in addition specialist technical skills—knowledge about corporate strategy and organizational restructuring [

15].

The literature provides some specific, interesting references to supply chains in Europe. Onar, Aktas, Topcu, and Doran [

16] traced the evolution of supply chain managers training by undertaking a comparative analysis of academic education programs in 2004 and 2011. They note that the progress in logistics education in that period was due to the changing needs of the industry. It has to be said, however, that in Poland, a firmly European country, logistics education began already in 1994, with the first academic handbook on supply chain management published in that year [

17]. In those early nineties, with the influx of direct foreign investments came technical knowledge, and competencies brought along by logistics specialists taking up positions in firms, mainly large corporations with foreign capital.

A question, therefore, arises: why have we decided to choose Polish firms to analyze the rationalization of logistics processes? The answer lies in the findings of long-term empirical studies, conducted in 390 companies in the period 2004–2020 [

18], which reported not only numerous instances of the implementation of the latest supply chain management methods, from just-in-time (JIT) inventory management, through MRP, CRM to fifth-party logistics, but also a systematic flow of capital to the industry, ranging from 19.5% to 30% annually. In this respect, Poland ranks among top Eastern European countries. The paradigms of Polish logistics, such as the impact of logistics on information asymmetry, or the new strategy of logistics in services, have been explored in Polish publications [

18].

As it turns out, the latest trends in global supply chains development call for new areas of research. A “best of both worlds” approach is to study simultaneously the specificity of the human resource management and logistics [

19]. The best research methods in this respect are case studies, secondary data analyses [

20], and, above all, survey research, which has become a predominant method in recent years.

A very significant and valuable contribution to the development of this field of knowledge is the combination of the personnel function research with the studies of company logistics, as undertaken by Polish scientists. As has been discovered, the nature of this relationship consists of feedback between the basic area of this function and rational selection of logistics management personnel in the Polish firm.

Some authors [

6] draw attention to new forms of the factors of production flows, specifically those connected with supply chain operations, for example:

Capital flows, including direct foreign investments into information technologies and logistics infrastructure;

Technical knowledge transfer, including a relocation of highly qualified supply chain managers endowed with key logistics competencies;

Reduction in the so-called “pure” flows of people, capital or technology in favor of a combined flow of all factors of production, both technical and cultural.

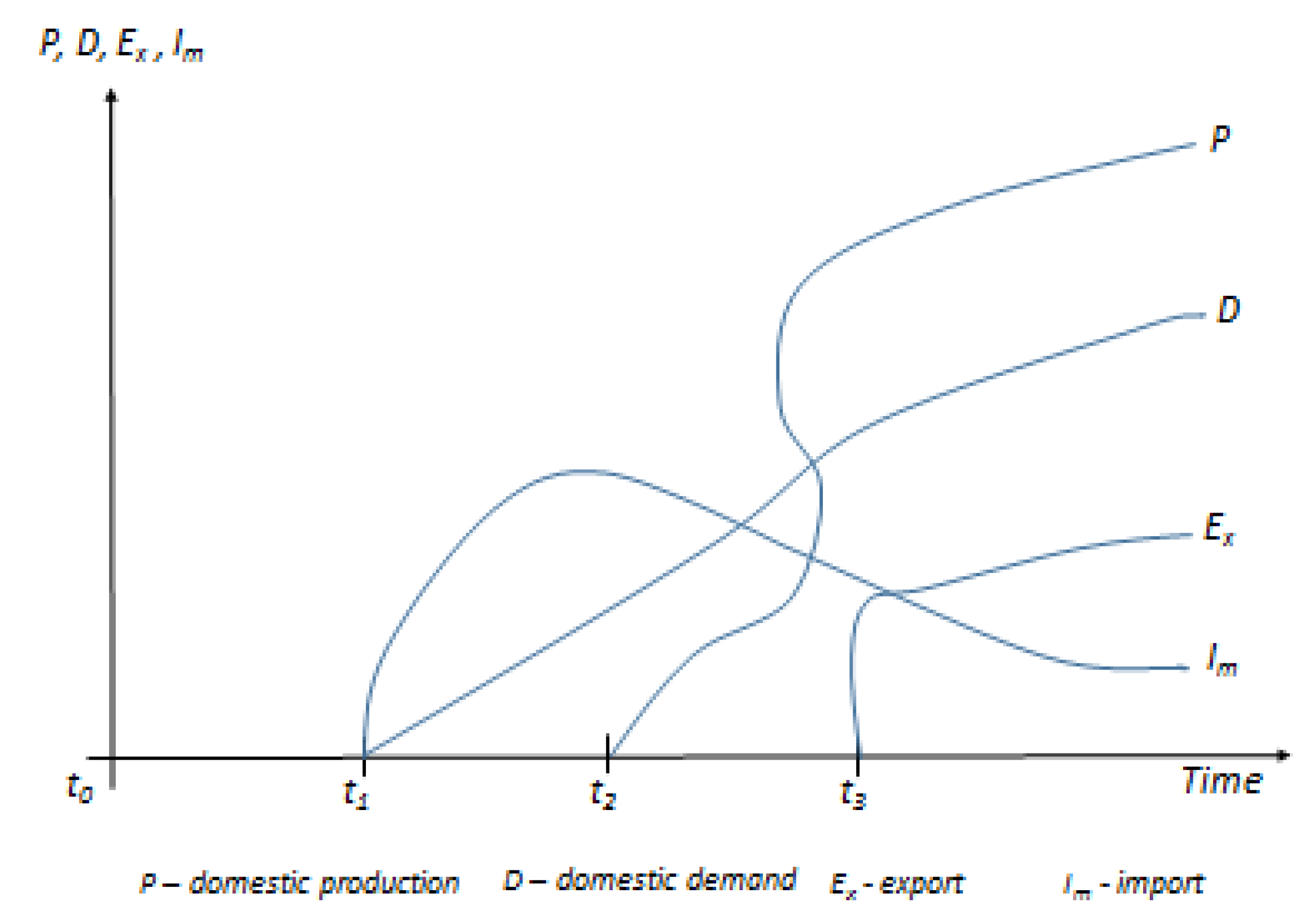

The latter is illustrated by a product life cycle model, known as the flying geese model (

Figure 1).

The intention of using the flying geese model is to illustrate the significance of the imports of not only products, but also technical knowledge, a force that drives domestic production. With reference to international logistics, the flow of logistics specialists between modern global enterprises contribute to the logistification of the world economy. In a broader context of workforce management in logistics, it can be said that human resource management is a new logistics paradigm.

The very recent publications of 2019–2020 present new developments in modern HR management in logistics. These include:

A new, original approach to HR management in logistics processes;

A novel approach to international human resource management;

New criteria for RIO value creation in international supply chains through knowledge transfer.

Re. (1) According to a new, original definition [

21], the personnel function is a set of expert and consultative people-related activities, aimed to deliver methods and tools for human resource management, with a view to achieving goals and a long-term value growth of an organization.

In this context, the essence of the relationship between the personnel function and rationality of logistics management lies in defining common strategies and value networks, in order to achieve expected outcomes, e.g., increased profits and material assets, or improved human resources.

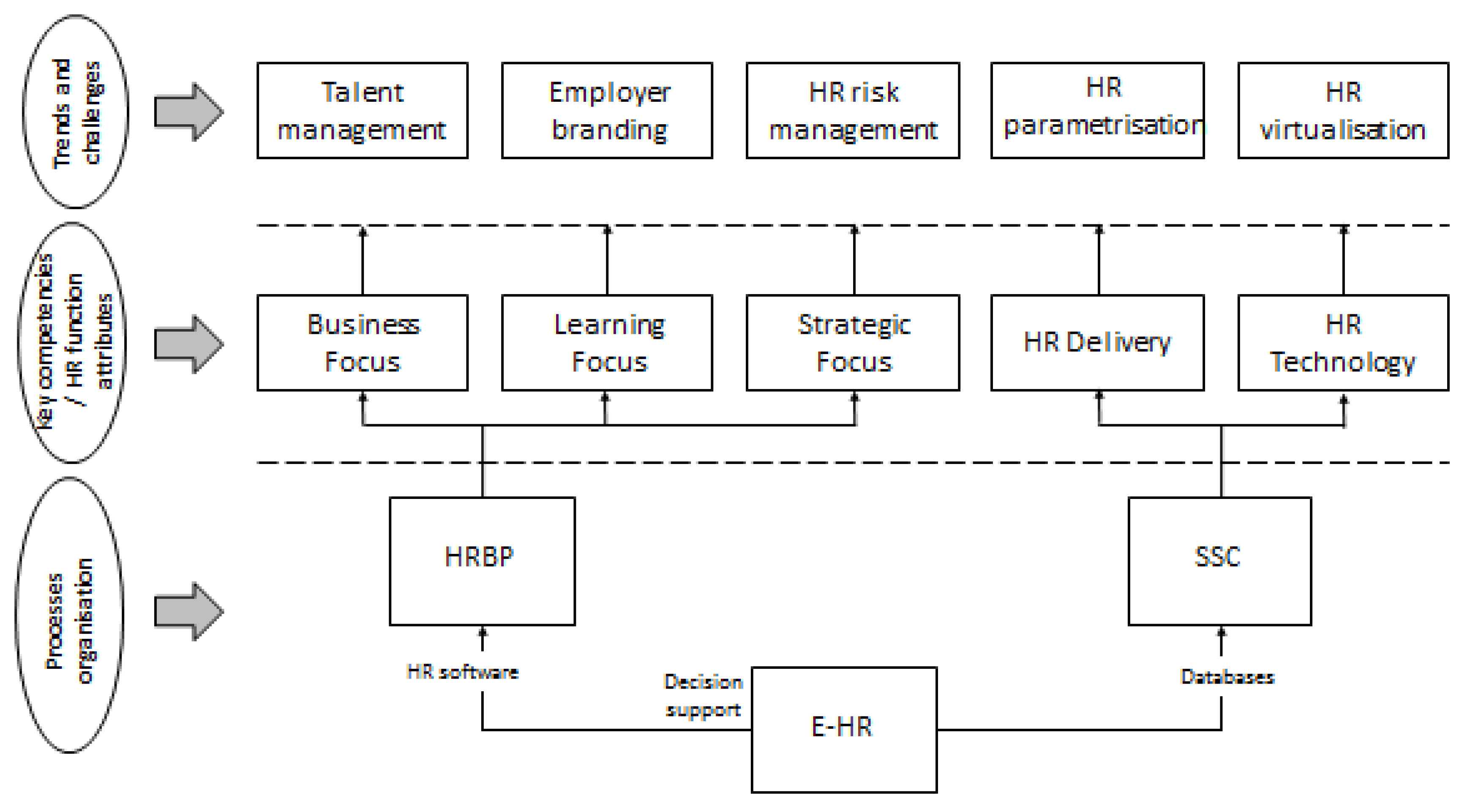

The following diagram (

Figure 2), illustrating the links between a business model and the personnel function, exemplifies such a relationship.

where:

It is hard to imagine a closer relationship between the personnel function and the requirements of logistics management in corporations.

Re. (2) Griffin and Pustay [

22], authors of the notion of international human resources management, claim that management internationalization is a consequence of factors such as the different economic levels of countries, and differences in national legal frameworks and cultures.

The scope of international human resources management in logistics requires that managers have versatile skills that are necessary to complete logistics operation both in their home country and in companies based in other countries. The way companies are managed depends on the level of their internationalization, and on the intensity of direct foreign investments.

As we know, in order to accomplish strategic goals in the area of production and finances, or in the implementation of logistics computer systems and software, international corporations primarily need HR managers. Interestingly, the cited authors identify three types of management teams:

Home country oriented—ethnocentric;

Host country oriented—polycentric;

World oriented—geocentric.

As it turns out, unlike Japan or the USA, European countries prefer the geocentric model, a fact confirmed by empirical studies in Polish firms [

18].

Re. (3) According to Peng and Meyer [

23] at the heart of the modern global supply chains creation is knowledge transfer. According to these authors, international supply chains must be characterized by:

Agility and flexibility, mainly because of the broad spectrum of global operations, often interrupted by unforeseen events such as acts of terrorism, epidemics, or natural disasters;

Adaptability, particularly with respect to new technologies and techniques, and because of possible sudden changes in supply chain configurations in different parts of the world;

A level playing field for all supply chain members; especially preferred are strategic alliances oriented towards the maximization of the participants’ profits.

The role and significance of added value in supply chains is also notable, and is built on the following attributes:

R—Rarity of products or services;

I—imperfect Imitability of resources and capabilities;

O—Organization of agile structures of supply chains.

A necessary condition for the added value creation in supply chains is, of course, knowledge transfer. This is often looked at as the sum of systems, structures, and processes enabling the development and flow of knowledge [

24]. Transport corporations, for example, run the schemes of multidirectional movement of specialist managers, thus facilitating the building of logistics networks of diverse configurations.

To summarize the discussion and the theses put forward in this part of the article, we may say that the role of HR management in logistics consists of:

A significant impact of HRM on the processes of internationalization and globalization of the economy and the flows of capital, workforce and knowledge, especially technical.

Creating the international management of human resources through the modern knowledge transfer in supply chains and in order to gain key logistics competences, whose acquisition relies on such management practices as talent management, personnel risk handling, or employer branding.

The empirical studies reported on in the subsequent part of this article were performed by the diagnostic survey method based on a questionnaire, which has been the preferred method for HR studies in logistics in recent decades [

25].

3. Selected Trends and Challenges of HR Management in Logistics

The personnel function in organizations is context-related and is sensitive to a variety of changeable factors. This implies that from time to time the HR management profession faces specific challenges, which have to be addressed by redesigning the way the personnel function is delivered. In order to identify these new challenges and the relevant management practices, the authors analyzed 41 reports published by leading consulting firms, containing the findings of studies on key challenges facing the personnel management profession in the immediate future. The time scope of the analysis is the period 2010–2018. The release dates of the reports were taken as landmarks for time-lining of the trends and challenges [

21]. A statistical analysis made it possible to identify the following set of HRM challenges:

Talent management;

Employer branding;

Personnel risk management;

Parametrization of the personnel function;

Virtualization of the personnel function.

The literature and various research findings [

25,

26] suggest that, for the purpose of contemporary (and certainly future) logistics management, the following challenges are particularly relevant:

Talent management with respect to large groups of specialists engaged in the design of international supply chains;

Employer branding, regarding logistics managers who create the company image, brand and employee value proposition (EVP);

Management of human resource risk, due to inadequate logistics competencies.

The authors believe that the first step in addressing the challenges is to implement a model of the HR function, such as the following (

Figure 3):

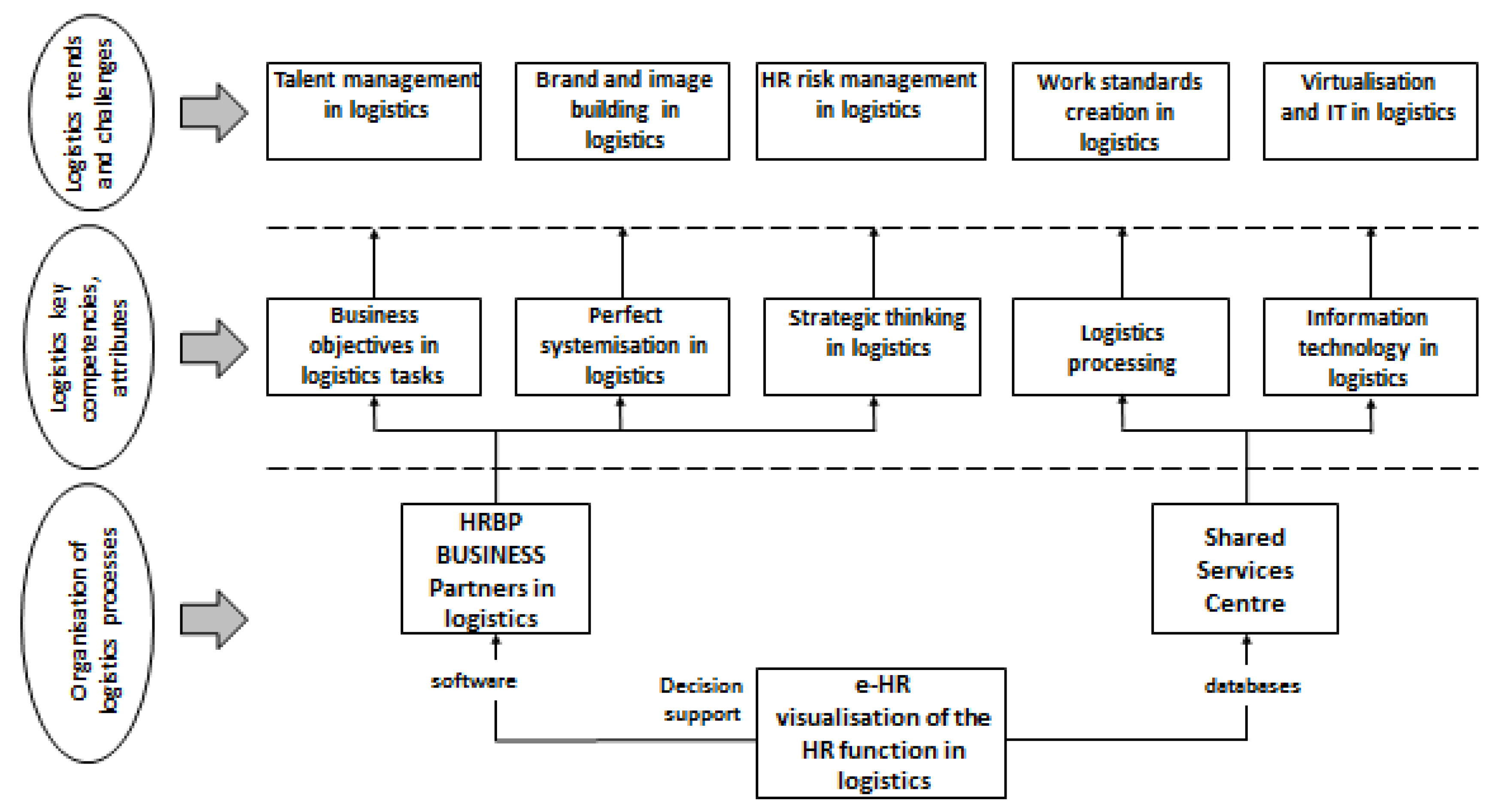

This model may also provide a basis for a working framework of all logistic management functions. Such a framework necessarily includes the logistics tasks, and methods of their effective delivery (

Figure 4).

It is essential that the company practices should be skillfully implemented: firstly, the process of talent management. According to Becker [

27], talents are employees with high value added who are difficult to replace. Therefore, talent management primarily consists of the search for and acquiring of talented individuals. In logistics, this is especially important, given that a talented logistician should possess a broad, interdisciplinary knowledge in the areas of economics, commodity science, and transport engineering. Irrespective of this broad knowledge, a logistician must have a creative imagination and the ability to recognize and respond to threats in business; in a word: the right person should possess an outstanding intuition, a talent not acquirable through training. The difficulty in recruiting a talented logistician lies in the recognition of the said features in a candidate for the job. Therefore, talent management is a leading skill of management professionals.

Talent management connects with employer branding, i.e., the creation of the company brand and image. Employer branding is a process, a sequence of planned actions, the purpose of which is to ensure that the company is perceived as an employer of choice [

28]. To attract and retain talented people, the company may extend to the potential and existing employees a so-called employee value proposition (EVP) [

29]. The EVP [

30] can be seen as a specific type of “contract” between the employer and the employee, defining a unique set of benefits an employee receives, in return for the work performed for the employer.

Finally, the ability to manage the personnel-related risk. Such a risk can be considered from two perspectives: the potential loss of human capital, and breakdowns in workplace communication.

Since the combination of logistics management with the company personnel function has an ambidextrous character, it bodes well for future changes. This can be referenced to the recent work by Binci, Belisari, and Appolloni [

30], in which the authors show the mutual relationship of TQM and BRP, and state that “the contextual factors such as leadership and people identity should be considered and managed as important variables related to change”.

Summarizing the discussion about the role and importance of HR practices in logistics management, we should also mention the geographic, political, and financial environment in which a firm operates, that is, the external conditions that have an impact on rational economic activity and effective management of companies. A valuable indicator of an effective delivery of HR management in logistics are the findings of empirical studies.

4. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the New Model of HR Management in Logistics. The Research Studies Findings.

The empirical studies concern both those aspects of the personnel function that have the greatest impact on the firm’s logistics and the effects of this relationship on logistics tasks. This type of research with such a broad scope of investigated problems, was the first in Poland. The unique results of logistics studies performed in Polish firms in the years 2004–2019 [

31] have led to a definition of a conceptual model of the personnel function in logistics management, allowing the identification of major mega-factors, having a decisive impact on the efficacy and effectiveness of company logistics tasks [

32].

The best research method, reflecting the current trends, is the survey of a randomly selected population, as it enables an in-depth factorial and structural analysis. The aim of the empirical research was, equally, to appraise the current state of the HRM design in logistics management, and to identify current trends in this area. The diagnostic survey was performed on a sample of 236 firms operating in Poland (

Table 1), divided into the following groups:

A stratified random sampling was used to ensure representativeness of the sample. To calculate the sample size, the following parameters were use:

Population size—3,772,931;

Fraction size—0.5;

Confidence level—0.95. The confidence level 1 − α is typically chosen at 0.95 or 0.99. The greater the confidence level, the smaller the allowable Type I error. The confidence level should therefore by carefully chosen. Higher 1 − α values are used in important technical, medical or epidemiological studies. In those cases, it is common to use the value 1 − α = 0.99, whereas, in market research or marketing studies, 1 − α = 0.95 is generally used (Babbie 2007).

To calculate the minimum size of the sample, values of two parameters must be assumed ex ante: the sample error (d) and confidence level (1 − α). The sample error (d), equal to 0.05, expresses the deviation of a sample parameter from the corresponding parameter of the population. In the reported study, the measurement error was assumed at 6.5%.

The quantitative studies were conducted between October 2017 and January 2018. The research tool was a survey questionnaire. The survey was conducted using computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI). The questionnaire contained 20 questions in total, and was composed of three main parts: (1) the respondent’s details, to classify respective companies into a specific group of entities; (2) the scope of HR management; (3) description of the HR function organization.

For statistical inference, the methods of descriptive statistics were used, including:

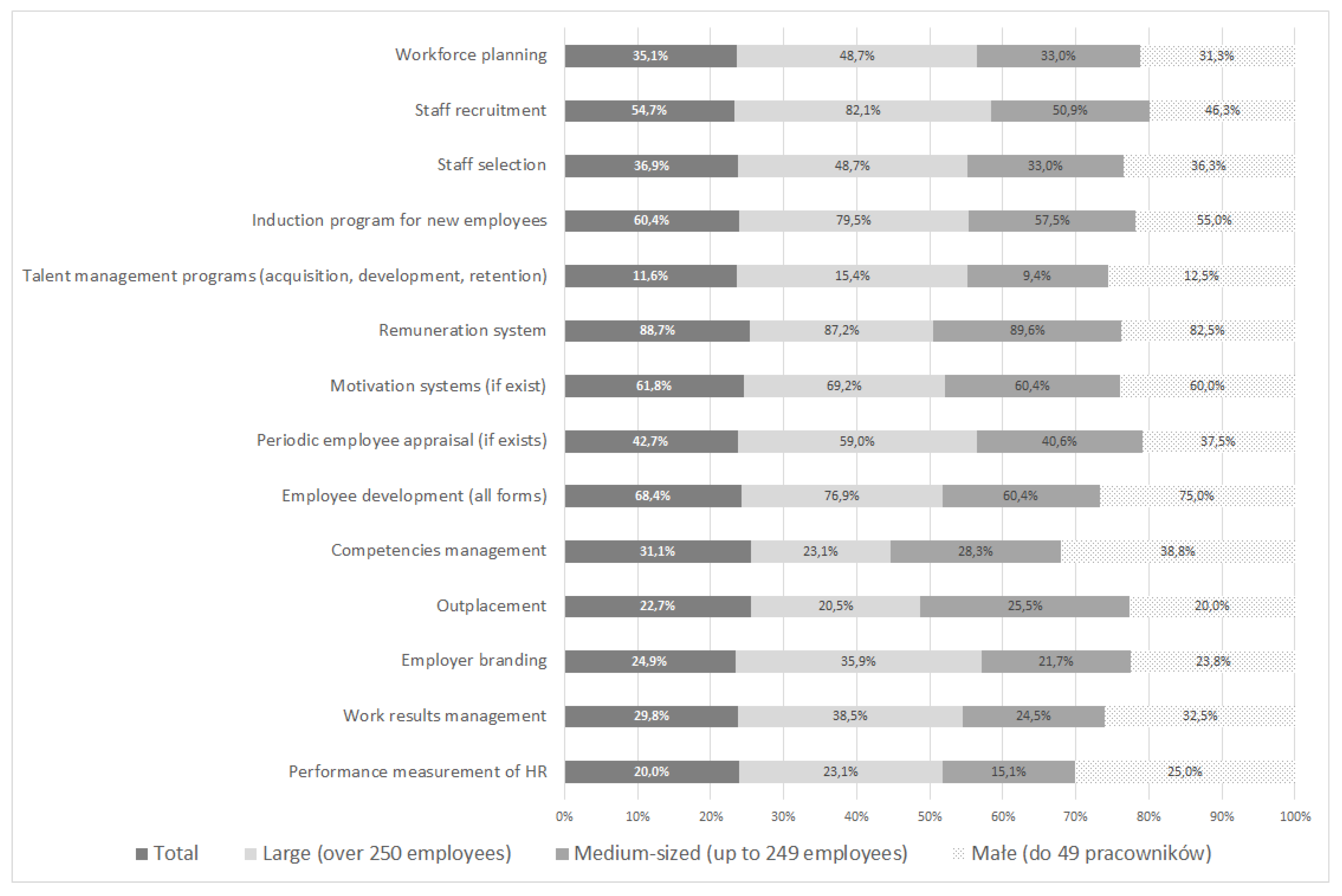

Firstly, a synthetic assessment of the present status of the HR function in the investigated firms was performed (

Figure 5).

As transpires from the data presented, remuneration and motivation systems are regarded as transactional processes (86.7% and 61.8% responses, respectively). On the other hand, the area of talent management (11.6%) is at an early stage of popularity, sending a signal that this HR management practice needs to play a greater role in logistics management.

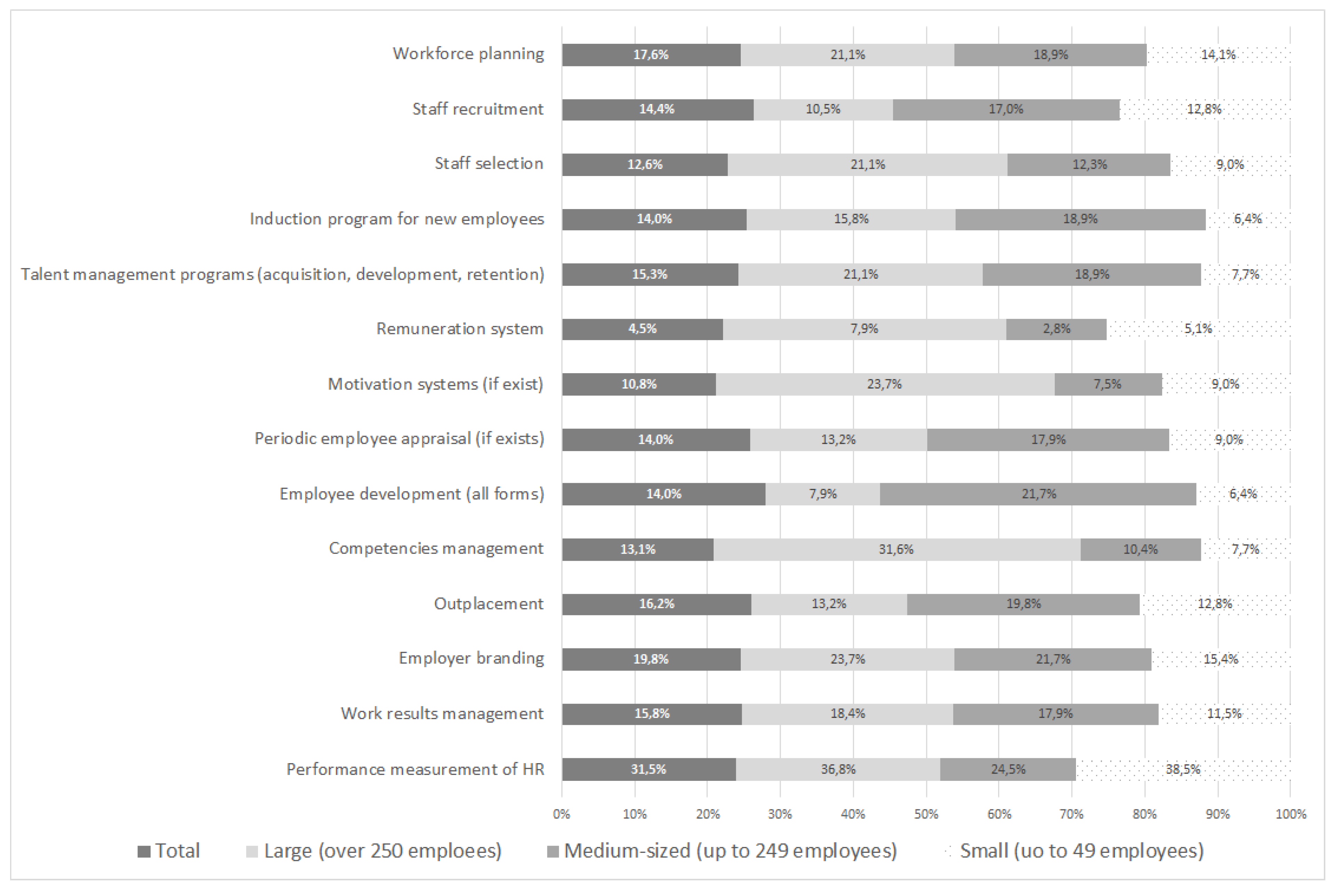

The practices planned to be implemented in the future were as follows (

Figure 6):

Analysis of the survey results allowed to identify six major areas—mega-factors—by consolidating selected practices enlisted in the diagram (65% of variations). Three of the mega-factors with the highest percentage scores deserve special attention. The first one, explaining almost 16% of the variations, for detailed calculations see [

21] includes work results management and HR performance measurement. These variables obviously determine the effectiveness of logistics operation. The second mega-factor, explaining 12% of the variations, contains one element, namely induction of new employees. This management practice is particularly important with respect to newly employed, highly skilled logistics managers. The greatest role, however, must be attributed to the third mega-factor (explaining 10% of the variations), which includes talent management, employee appraisal systems, and competencies management. The talent (and competencies) management has a fundamental impact on logistics management teams who create logistics solutions in the entire international supply chain. The three remaining mega-factors have lesser or moderate impact on the performance of logistics tasks, nevertheless, all management practices aimed at improving the personnel function, especially in logistics, are important.

The most important observation that can be drawn from the data is that the HRM function assumes a new quality, taking a role in the creation of business strategy. How does it connect with logistics? The connection is obvious, seeing that within international logistics, and considering a broadly understood logistification of the world economy, logistics is a strategy, by inference co-creating the business strategy of a company.

Additionally, the implementation of the HR management function provides operational support for managers, including logisticians. In this respect, the following conclusions can be drawn from the studies:

A phenomenon, and even a clear trend of decentralization of the HR management function, has been identified. In practice, this is affected by creating teams of logisticians on company boards, and the outsourcing of specific logistics tasks.

An imbalance has been observed in the level of HR management implementation between large and medium-sized firms on one hand, and small companies operating without teams of logistics managers on the other.

A growing awareness has been observed among logistics managers regarding the need for talent management, or personnel risk management.

In light of the discussion thus far, and considering the results of the empirical study, a new model of HR management delivery in company logistics can be cautiously proposed (

Figure 7).

The model of HR management in company logistics presented above is merely a first attempt at characterizing this very important relation between the management of de facto human resources, and the management of material resources through the performance of logistics tasks. The twenty-first century, an era of artificial intelligence, makes us look for rational ways of profiting from human knowledge. Logistics is a science that requires logical thinking about the real economy, and can support human capital management in all aspects of the process.

Additionally, the extremely valuable and up-to-date research findings concerning Polish firms represent an added value in the context of international business collaboration. Rapid changes occurring in human capital flows, particularly in EU member states, require understanding of the principles of deployment of high-class logistics specialists between firms in different countries. Therefore, knowledge about the human resource management conditions, especially with respect to Polish logisticians, is useful for firms collaborating with Polish companies in many industries and sectors of the economy.