1. Introduction

“Firms do not survive and prosper, solely through their own individual efforts, as each firm’s performance depends in important ways on the activities and performance of others and hence on the nature and quality of the direct and indirect relations a firm develops with these counterparts” [

1] (p. 123). This dependency between companies implies that relationships among companies are of increasing importance today. As various research papers indicate, company relationships based on collaboration are linked to higher performance [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, consensus has emerged that competition in the market has shifted from firm against firm to supply chain against supply chain [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, supply chain management (SCM) has greatly increased in importance and with supply chains, today is seen as a potential source of competitive advantage [

11,

12,

13]. Many studies have shown that excellent SCM practices generate an increase in financial performance [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, although many researchers have come to comparable conclusions, each study was carried out in different ways and analyzed financial performance with different measures [

10]. Although one group of researchers used accounting-based measures [

11,

13,

16], another group used market-based measures [

18], or a combination of both [

14,

17]. While most of these studies tried to differentiate between more and less successful firms, some investigations used established rankings. For instance, Greer and Theuri [

15] applied Gartner’s (formerly AMR) Supply Chain Top 25 ranking, in order to link SCM superiority to multifaceted firm financial performance. The authors showed the superior financial performance of these supply chain leaders (SCLs). However, within their analysis, Greer and Theuri [

15] neglected to examine the impacts on the affiliated supply chain business partners of these leading companies. Do the affiliated suppliers and customers of these SCLs benefit to the same extent, or is the success of the SCLs, in contrast, based on the exploitation of their market position? In a more generalized way, Crook and Combs [

19] pointed out that today there is consensus on the positive influence of effective SCM on firms’ performance, but less attention is given to the distribution of the gains through a supply chain. It is interesting to understand whether other members in an “outperforming” supply chain derive benefit from this kind of leadership, too, and, if so, how. Thus, we try to close this gap by focusing on suppliers and customers of SCLs and analyzing their (accounting-based) financial performance. We call such a financial reaction in the supply chain a “financial spillover effect”.

The question of whether and how affiliated suppliers and customers benefit from leading supply chain companies is mainly discussed with the topic of supply chain relationships. In that sense, Kim and Henderson [

20] classified supply chain relationships as of either a competitive (associated with power) or cooperative (associated with embeddedness) nature. Commonly, studies in the context of power relations have analyzed the dominant position of buying companies (customers) and highlighted a negative impact on suppliers’ financial performance [

21,

22,

23], especially a negative effect on profitability [

24]. Even confronted with powerful customers, in some cases, suppliers have also been associated with positive returns in terms of liquidity ratios, such as shorter cash conversion cycles [

25]. Contrarily, studies analyzing the cooperative nature of supply chain relationships use different—often non-financial—performance data [

26,

27], making a comparison difficult. Cooperative-dominant studies even focus on the affiliated suppliers’ or buyers’ operational performance improvements or efficiency effects [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Thus, there has only been limited comprehensive analysis in the literature of the financial performance implications for the affiliated suppliers and customers of leading supply chain firms [

21,

22,

31]. Herein, “comprehensively” means an impact analysis in terms of liquidity, financial activity and profitability measures.

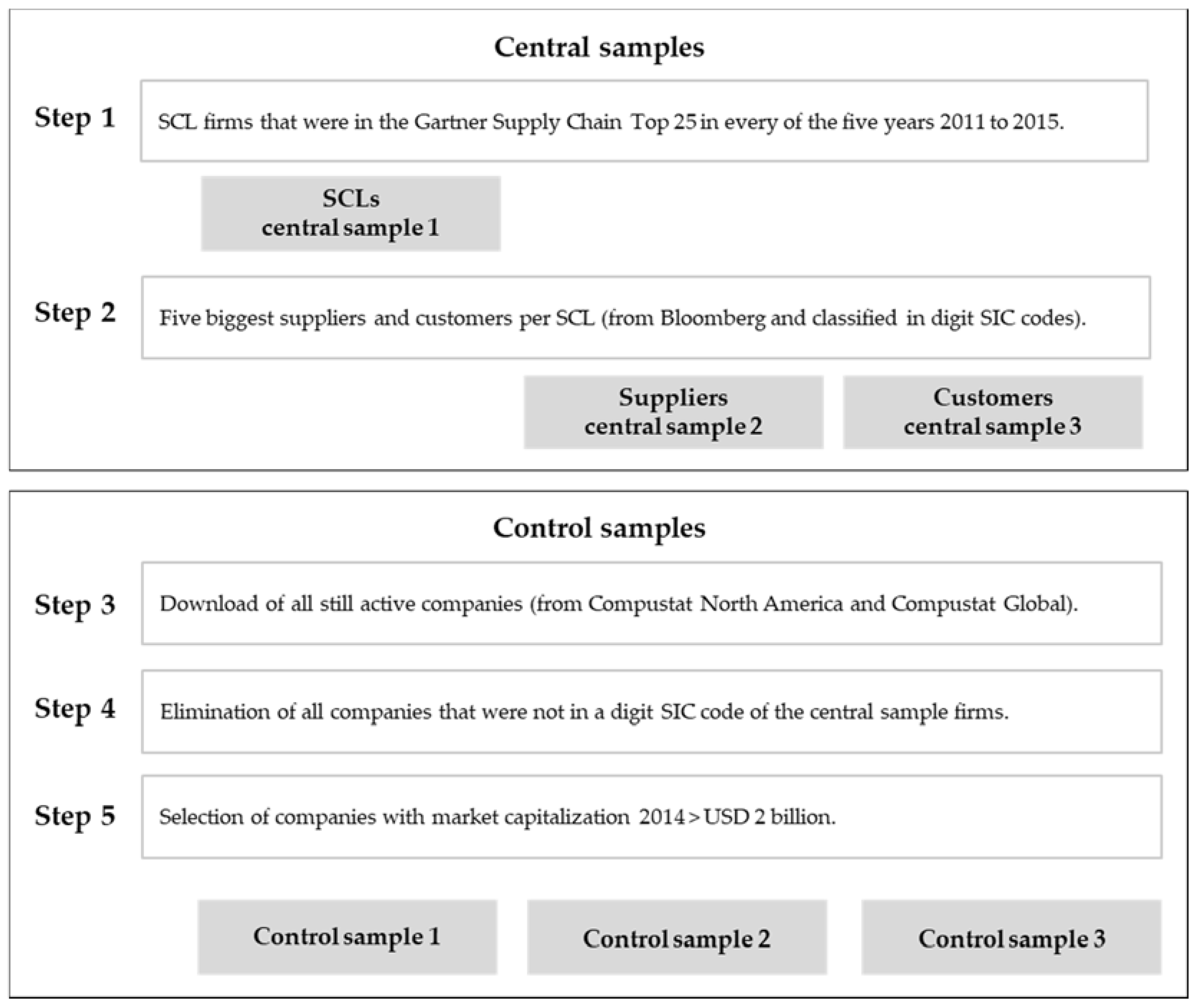

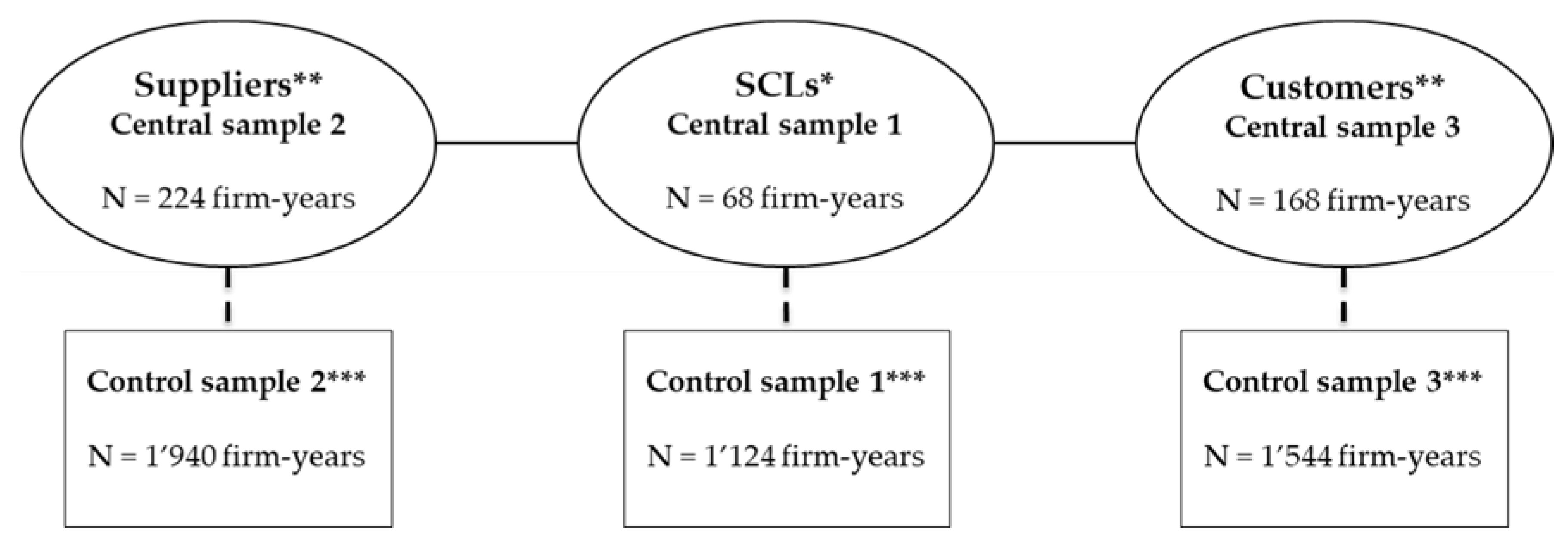

Based on these gaps, the present study tries to answer the following research question: “Do suppliers and customers of SCLs demonstrate superior financial ratios compared to those of other companies from the same industry?” The purpose of this study is to investigate the financial spillover effect in supply chains and whether suppliers and customers may derive beneficial advantages from participating in an SCL’s network. The study is carried out by selecting firms from the three central samples (SCLs, SCL suppliers and SCL customers). We collect financial statement information about SCLs’ key customers and suppliers. The control samples are established by taking firms from the same industry. The analysis is based on secondary data (financial ratios). The usage of secondary data to build or elaborate theory is common in finance research. This is also becoming increasingly common in supply chain and industrial organization research, as suggested by Rabinovich and Cheon [

32] and Busse [

33]. We assume that publicly available practices—affiliation with a certain supply chain network—can explain variations in firm-level (financial) performance. Based on Gartner’s Supply Chain Top 25 ranking, we identified a set of SCLs. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was conducted. Following an explorative study approach with abductive reasoning, we identify some interesting correlations and state propositions at the end.

This study shows that suppliers and customers are associated, on one hand, with superior liquidity and activity and, on the other, with inferior profitability ratios compared with peers from the same industry. These findings confirm the existence of financial spillover effects in supply chains, highlighting correlations between supplier and customer ratios and demonstrating that SCLs’ business partners can derive financial performance benefits (and losses) from their participation in an SCL network. In accordance with Kim and Henderson [

20], it is suggested that in such supplier–customer relations, competitive and cooperative relationships co-exist. The present findings also contribute to the work of Gulati and Sytch [

28] who, in relation to interdependency, distinguished between asymmetry dependency (in terms of the logic of power) and joint dependency (in terms of the logic of embeddedness). The contribution for practitioners is a profound understanding of the potential consequences of participating in an SCL’s network. Nevertheless, this topic warrants further exploration in future studies.

This paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, the theory and a literature review about the central topics are provided. In

Section 3, the methodology is presented, explaining the explorative study approach with abductive reasoning, data sources, sample selection and data analysis methods. In

Section 4, the results for each of the three samples are highlighted separately. In

Section 5, the findings are discussed, and propositions are put forward. Finally, in

Section 6, a conclusion is given, as well as implications for theory, practice and future research.

4. Results

4.1. Relationship Distribution

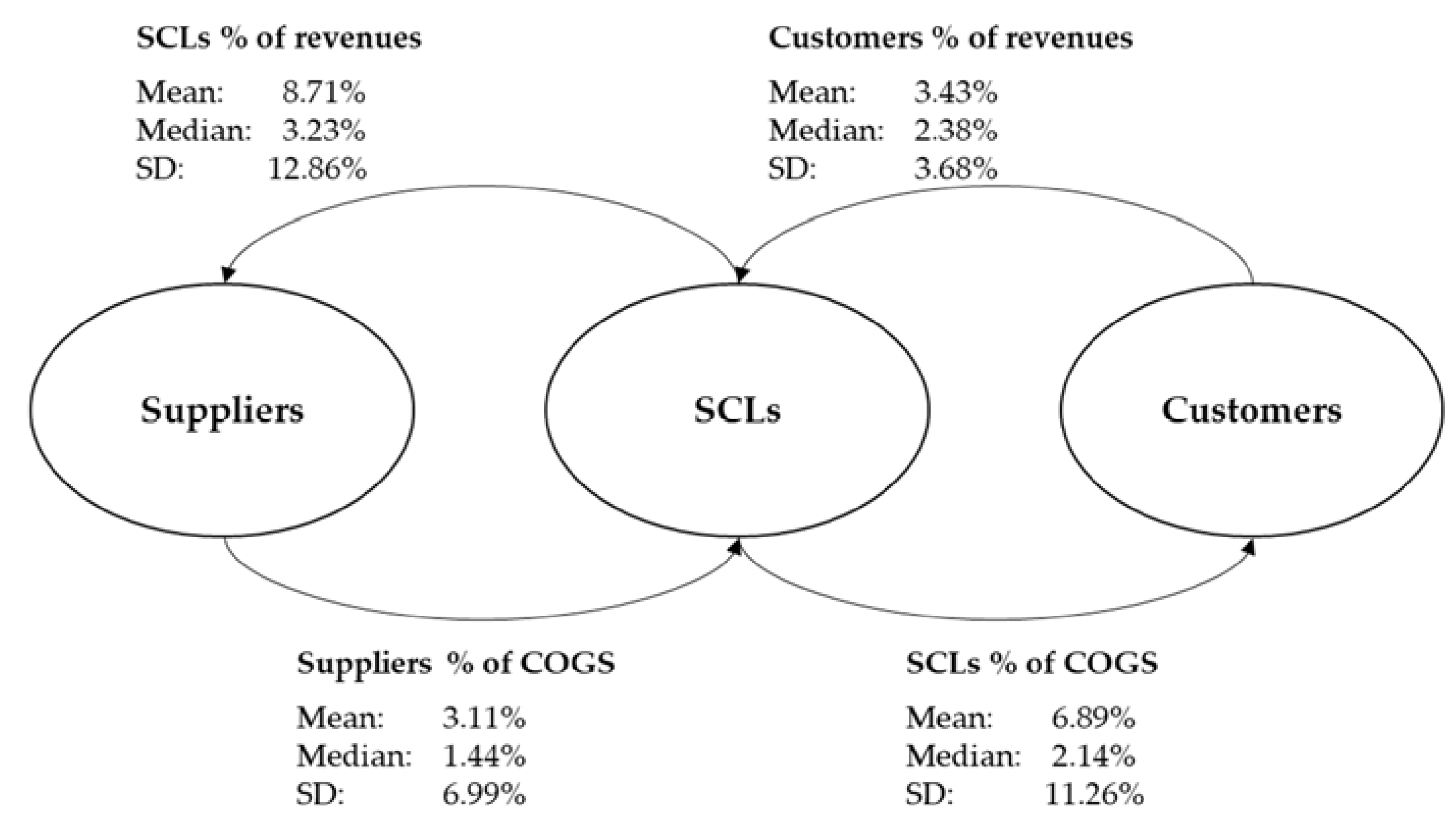

Before the results are described, the relationship between the supply chain members and the central samples’ distribution in industries is briefly shown. This provides the basis for the discussion and helps to interpret the findings. The relationship between suppliers and SCLs and SCLs and customers is displayed in

Figure 3. It shows the companies’ percentage of revenue or COGS they impact. For the data information, the mean, median and standard deviation (SD) of the analyzed companies are provided. Generally, it appears that SCLs have a lower percentage (in the mean and the median) in costs and revenues than the suppliers and customers. This shows that SCLs are less dependent on their relationship with suppliers and customers than vice versa. Looking at the suppliers and customers, it becomes clear that suppliers (SCLs % of revenues) are the most dependent companies. They exceed the customers (SCLs % of COGS) by 1.82 percentage points in the mean and by 1.09 percentage points in the median.

Table 3 classifies the central samples in the SIC divisions, in order to get an initial impression of the position of the sample companies in the supply chains. Although most of the SCLs (70.6%) and suppliers (85.7%) are active in the manufacturing division, 40.5% of the customer firms work in the retail trade business. Many customer companies are also active in manufacturing (38.1%). See more information about the classification of the samples in SIC code in

Appendix A and about the samples descriptive data in

Appendix B.

The descriptive results illustrate that whereas SCLs and suppliers are one step before the consumption point, most of the customers have direct contact with end consumers.

4.2. Supply Chain Leaders (SCLs)

In line with Greer and Theuri [

15], we conducted an analysis to confirm their results, that SCL firms have significantly better financial ratios than control firms in the same industries.

Table 4 presents the results for SCLs. Although 76.5% of the analyzed companies are from the US, all firms are at least large caps (70.6%) or even bigger, mega-caps (29.4%). Far more than half of the companies (70.6%) have more than 100,000 employees.

In the following, each ratio result is briefly described (mainly the medians).

Liquidity Ratios. The operating cycle (91.383 for SCLs vs. 112.072 for control firms) and the CCC (34.483 for SCLs vs. 46.534 for control firms) of SCL firms are statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level). The current ratio (1.351 for SCLs vs. 1.512 for control firms) is also shown to be statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level). A general rule for the current ratio is that it should total 200% (this means looking at the results 2) and be at least 100%. In this case, the control firms seem to have safer current ratios, which contradicts Greer and Theuri’s [

15] (pp. 102–103) findings. Even if the control firms seem to have a better ratio, the SCLs’ current ratio nevertheless exceeds the minimum limit of 1. The cash turnover (11.130 for SCLs vs. 8.260 for control firms) of SCLs, however, is statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) compared with that of the control firms. The lower operating cycles and CCCs together with the higher cash turnover ratios imply that SCL firms are associated with significantly better liquidity ratios than control firms in the same industries.

Activity Ratios. The statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) receivables turnover (10.692 for SCLs vs. 9.105 for control firms), together with the statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level) DIO (60.541 for SCLs vs. 63.505 for control firms) show that SCL firms have better activity ratios compared to firms in the same industries.

Profitability Ratios. The EBIT margin (18.335 for SCLs vs. 10.149 for control firms) and the ROCE (32.306 for SCLs vs. 20.234 for control firms) of SCL firms are statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) than their respective industry benchmarks. The COGS to sales ratios (51.924 for SCLs vs. 55.584 for control firms) are shown to be statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level) than that of peers in the same industry. The SG&A to sales ratios are higher (25.307 for SCLs vs. 20.320 for control firms) for SCLs, but the results do not reach statistical significance. This seems to be in line with the results obtained by Bharadwaj [

70] (p. 182) for IT leaders. In sum, the higher EBIT margin and ROCE and lower COGS to sales show that SCL firms are associated with better profitability ratios.

In summary, SCLs are associated with significantly superior liquidity, activity and profitability ratios. These results are in harmony with that of Greer and Theuri [

15]. The following analysis extends their study by analyzing the suppliers and customers of SCL firms.

4.3. Suppliers

The suppliers of SCLs are, similar to the SCLs for their part, mostly US companies (51.8%). Around one fifth (21.4%) of the firms in this sample are from Asian countries: Japan (8.9%), South Korea (7.1%) and Taiwan (5.4%). The majority of the suppliers are large caps (42.9%) and mid-caps (39.3%). Most (67.8%) have more than 10,000 employees, 21.4% of which have more than 100,000 workers. Compared to the SCLs sample, the suppliers’ sample contains smaller companies: 85.7% of these firms are active in the manufacturing SIC division. The results for the suppliers of SCL firms are displayed in

Table 5.

Liquidity Ratios. The operating cycle (96.995 for suppliers vs. 113.558 for control firms) and the CCC (44.473 for suppliers vs. 59.893 for control firms) of the SCL suppliers are statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level) compared to that of control firms in the same industry. The current ratio (1.495 for suppliers vs. 1.732 for control firms) is also statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level). Similar to the SCLs’ current ratio, in this case, the control firms’ current ratio is closer to 2. Consequently, the same as for the SCLs is true here. The cash turnover (11.164 for suppliers vs. 8.150 for control firms) of suppliers, however, is statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) compared with that of the control firms. The lower operating cycle and the CCC together with the higher cash turnover ratios imply that SCL suppliers are associated with significantly better liquidity ratios than control firms in the same industries.

Activity Ratios. The Wilcoxon signed rank test indicates that the receivables turnover (8.420 for SCL suppliers vs. 7.477 for control firms) and the asset turnover (0.941 for suppliers vs. 0.771 for control firms) are statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) than those of the control firms in the same industries. In contrast, the DIO (51.290 for suppliers vs. 63.836 for control firms) are statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level). This result shows that SCL supplier firms also possess significantly better activity ratios.

Profitability Ratios. There is evidence (at the 1% level) that SCL suppliers’ EBIT margins (6.582 for SCL suppliers vs. 10.697 for control firms) are statistically significantly lower than the industry benchmarks. The COGS to sales (78.890 for suppliers vs. 66.895 for control firms) ratios are statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) than that of the control firms in the same industry. As the ROCE and the SG&A to sales ratios do not present statistically significant results, SCL suppliers possess smaller profitability ratios.

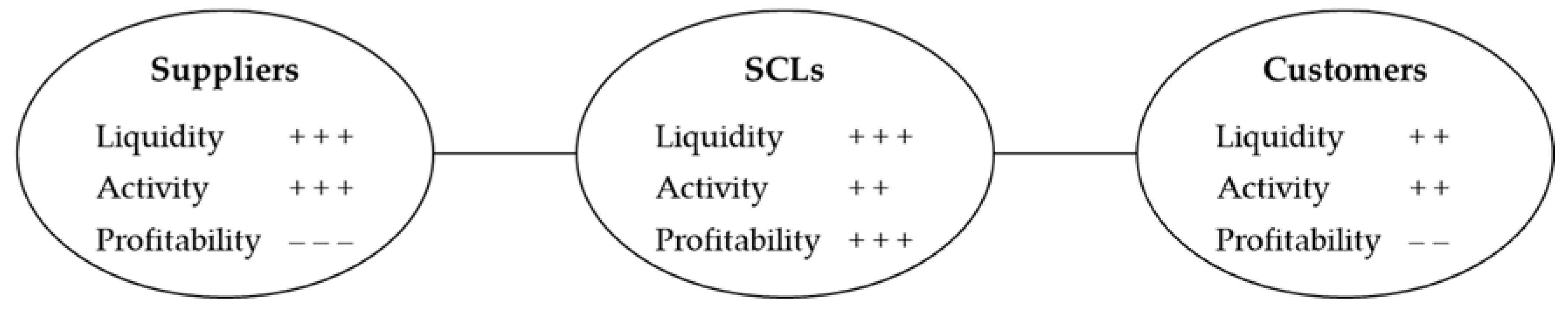

In summary, suppliers of SCLs are associated with significantly superior liquidity and activity but inferior profitability ratios.

4.4. Customers

The majority of the SCL customer firms are US companies (47.6%). A smaller portion of companies (26.1%) are from Japan (9.5%), Great Britain (9.5%) and France (7.1%). The majority of the firms are at least large caps (76.1%), of which 7.1% are mega-caps. Most of the customers (61.9%) have more than 100,000 employees. This shows that this sample, compared to the SCL suppliers’ sample, is made up of bigger companies. The majority (40.5%) of these firms are active in the retail trade SIC division: 38.1% of the firms are in the manufacturing sector and 14.3% in the transportation and public utilities SIC division. The results for the customers of SCL firms are displayed in

Table 6.

Liquidity Ratios. The operating cycle of SCL customers (66.288 for SCL customers vs. 88.494 for control firms) is statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level) compared to that of control firms in the same industry. In addition, the CCC as the current ratio presents misleading results if the mean and the median are compared. Further, neither ratio has statistically significant results. The cash turnover (14.830 for customers vs. 11.538 for control firms) of customers is statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level) compared to that of control firms in the same industry. The lower operating cycles, together with the higher cash turnover, imply that SCL customer firms are associated with significantly better liquidity ratios than control firms in the same industry.

Activity Ratios. Although the receivables turnover for SCL customers (11.567 for SCL customers vs. 9.487 for control firms) is statistically significantly higher (at the 1% level), the DIO (38.229 for SCL customers vs. 48.956 for control firms) are statistically significantly lower (at the 1% level) than that of control firms in the same industry. These results show that SCL customer firms are associated with significantly better activity ratios.

Profitability Ratios. The test statistic shows that SCL customers’ EBIT margins are statistically significantly lower (at the 5% level) than the industry benchmarks. In addition, although the SCL customers’ mean is smaller than that of the control samples’, the median is higher. This says something about the distribution of the data. This effect could be because the average distance of the firms’ ratios above the median is smaller, and/or the average distance of the customers’ ratios below the median is larger. Further, the COGS to sales ratio is statistically significantly higher (at the 5% level) than that of control firms in the same industry. For the COGS to sales ratio, the same phenomenon as for the EBIT margin appears, only inverted. Although the ROCE as the SG&A to sales ratio does not present significant results, SCL customers have smaller profitability ratios than their peers.

Summing up, customers of SCL firms are associated with significantly superior liquidity and activity but inferior profitability ratios.

5. Discussion

5.1. SCL Networks as a Source of Liquidity

By analyzing supplier–buyer relationships, Patatoukas [

25] showed that suppliers, among others, can reduce their CCC through relationships with major customers. Lanier et al. [

24], by investigating a concentrated three-firm SC, demonstrated that positive CCC results are distributed across the supply chain, with some indication that upstream members benefit more. Furthermore, Gosman and Kohlbeck [

21] showed that suppliers of powerful retailers are associated with a lower CCC. These results are, to some extent, in line with our results in which suppliers and SCLs have statistically significantly superior liquidity ratios. Although SCL suppliers display a 15.4 day shorter CCC against peers, SCL firms for their part show a 12.1 day shorter CCC compared to their control samples. By deepening the results, it becomes clear that SCL suppliers have superior operating cycles and CCCs, while SCL customers are associated only with superior operating cycles. The customers’ CCC seems to be inferior, but with no significance. These results could be explained by a few factors. On one hand, in line with Gosman and Kohlbeck [

21], as well as Gosman and Kelly [

62], the suppliers seem to balance some of the negative effects, by transferring some of the negative performance effects to their suppliers (upstream the supply chain). In addition, looking at the suppliers–SCLs’ relationship, it seems, in line with Hofmann and Kotzab [

84], as if there is an improvement of the CCC in the supply chain through an optimization at the external supply chain boundaries. However, customers seem to be unable to offset the pressure of SCLs through their respective customers and are forced to pay SCLs more quickly, which reduces their accounts payable. Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that for the customers the CCC was not found to be significantly inferior. Thus, even if it seems that customers are under pressure by SCL firms, customers still possess superior liquidity ratios.

As the present results significantly show, suppliers and customers of SCL firms are associated with superior liquidity ratios, which suggests that these firms can better meet short-term obligations. Thus, our first proposition is as follows:

Proposition 1. Within an SCL’s network, cash is provided for suppliers and customers associated with superior liquidity ratios for the affiliated supply chain partners.

This proposition is in line with the “(liquidity) redistribution thesis” as suggested by Meltzer [

85], Petersen and Rajan [

86] and Cuñat [

87], who posit that firms with better access to capital redistribute the cash to less advantaged firms. This means, in general, suppliers are paid faster by SCLs [

88], and customers are granted longer payment terms [

89]. In a figurative sense, the supply chain with a financially strong SCL firm serves as a source of liquidity for the affiliated up- and downstream members—an insight which should be paid much more attention in future supply chain investigations.

5.2. SCL Networks as an Accelerator for Activities

Looking at the activity ratios of suppliers and customers, the results are analogous to liquidity ratios and show superior results compared to industry peers. As previously seen, the ratio categories are not mutually exclusive, meaning, for example, that sometimes activity ratios could also be useful for calculating the liquidity of a firm [

46]. Therefore, the previous and following sections should not be strictly separated.

Looking at the supplier side, the activity ratio results are in line with Patatoukas [

25], who found that suppliers reported lower assets in inventory and higher asset turnover. Lanier et al. [

24] suggest that asset utilization is shared between the members, noting that this resource distribution is central to the competitive advantage of the supply chain. Previous articles and studies have shown that buyer power, created by retailer consolidation, enables the dominant party, among others, to carry less inventory and extend payables to suppliers [

21,

22,

62,

90]. In contrast to these studies, the present results showed that suppliers and customers have superior activity ratios. Although suppliers are associated with higher receivables turnover (0.9 higher than the control firms), higher asset turnover (0.2 higher than the control firms) and 12.5 day shorter DIO against peers, customers show a 2.1 higher receivables turnover and 10.7 day shorter DIO.

The present results can be explained by the “knowledge transfer thesis” [

21,

62] and the joint learning approach, meaning that successful firms (like SCLs) establish their practice excellence by suppliers and customers. This is in line with the well-studied relevance of long-term relationships in supply chains [

91,

92]. Ford Motor Company is an example, showing that a change from an adversarial to a cooperative relationship with suppliers can improve competitiveness [

93]. Extending that idea, Carr and Pearson [

60] found empirical evidence that a cooperative relationship between suppliers and buyers increases both companies’ performance.

As suppliers and customers of SCL firms are associated with superior activity ratios, these firms are able to manage their resources more efficiently. We suggest a second proposition:

Proposition 2. Within an SCL’s network, suppliers and customers will benefit from know-how exchange associated with superior activity ratios for the affiliated supply chain partners.

5.3. Profitability Exploitation across SCL Networks

In addition, by looking at the suppliers’ and customers’ profitability, the results are unambiguous. Both are associated with statistically significantly inferior ratios compared to those for the control firms in the same industry.

Referring to our analysis, suppliers showed clearer tendency (at the 1% level of significance) than customers (at the 5% level of significance). Although suppliers exhibited a 4.1% lower EBIT margin, their COGS to sales ratio was 12.0% higher, which demonstrates their profitability ratios’ inferiority compared to their peers. The customers’ EBIT margin and COGS to sales ratio results compared to the control samples show different and confounding means and medians. This result says something about the data distribution and not the statistical results. The difference between the customer ratios and those of the control peers is smaller than that of suppliers.

In a supplier–SCL or SCL–customer relationship, the powerful actors are per definition the SCL firms, as they are commonly bigger companies, which are less dependent on their supply chain partners (see

Appendix B). Following our results, it could be suggested that SCLs exploit their power by profitability ratios. Duffy and Fearne [

63] showed that power asymmetry is negatively associated with sharing of benefits between partners. Especially on the supply side, studies have shown that buyer power is negatively associated with suppliers’ profitability. For instance, Gosman and Kohlbeck [

21] found that suppliers’ gross margin and ROA are negatively correlated with an improvement in sales to major customers. A reason could be the influence of dominant actors over suppliers that are forced, for example, through open-book accounting practices to provide information about cost and profit to their powerful partners, which can use this information to enforce price reductions [

62]. This is in line with Bianco and Zellner [

90] who pointed out that, for example, a firm like Wal-Mart strongly influences prices by cost reductions of products among its upstream business partners.

Based on these argumentations, we conclude with the third proposition:

Proposition 3. Within an SCL’s network, concessions must be made by suppliers and customers associated with inferior profitability ratios for the affiliated supply chain partners.

In addition, the “profitability waiver thesis” seems to be an alternative reason for this third proposition. Based on the strategic choice approach, a profitability waiver can be interpreted as a sort of “interest rate” to pay, with the SCL as a customer (from the perspective of the suppliers) and with the SCL as an important brand supplier (from the perspective of the customers). This is not to say that such relationships to SCLs are less attractive; instead, the profitability waiver seems to be a conscious compensation of being part of the SCL’s network. Suppliers and customers of SCLs are willing to accept the waivers as they intend to build up a dependence relationship in their favor [

53]. The higher the dependency in favor of the SCL, the more willing SCL suppliers are to accept a discount on their sales and the more willing SCL customers are to accept a substantial price premium. Thus, future supply chain investigations should stress much more the “concession motivations” of suppliers and customers being part of a SCL network.

5.4. Two-sided Financial Characteristics of SCL Networks

Surprisingly, the present study shows multilateral implications for suppliers and customers of SCL firms. The results suggest benefits for suppliers and customers of SCLs in terms of liquidity and activity ratios but also indicate that SCLs to some extent exploit their partners’ profitability through the power the SCLs possess.

The multilateral implications for suppliers and customers suggest two-sided behavior by SCL firms with their affiliated supply chain partners. Based on Emerson [

94], Gulati and Sytch [

28] state the importance of considering two different dimensions when analyzing interdependence: asymmetric dependency (in the logic of power) and joint dependency (in the logic of embeddedness). The present results seem to confirm these interdependencies. It can clearly be seen that in both relationships (suppliers–SCLs and SCLs–customers), there is an asymmetric dependence, where suppliers and customers are much more dependent on their SCLs than vice versa. A joint dependency in these relationships can only be suggested as an explanation for the two-sided findings and the fact that suppliers and customers also benefit from their relationships with SCLs. Brányi and Józsa [

7] came to a very similar conclusion: Cooperation can also exist when a firm has power.

According to our discussion, we formulate the following proposition:

Proposition 4. Within an SCL’s network, SCL firms, on one hand, dominate their suppliers and customers, but, on the other hand, they also depend on these affiliated supply chain partners.

By analyzing concentrated three-firm supply chains, Lanier et al. [

24] showed that in such constellations, although the profitability is principally earned by downstream members in the supply chain, the CCCs are earned across the supply chain. One reason for the better profitability of downstream members was that the power in a chain is derived from the relationship with the ultimate consumer and the position as the manager of the consumption point [

95]. The present study results are to some extent in contrast with these observations, considering that most of the profitability is captured from the dominant SCLs in the middle of the chain. It could be suggested that SCLs, with their powerful position, steer and manage the supply chain’s financial performance. On one hand, SCLs seem to allow their partners to have better liquidity and resource utilization conditions. On the other hand, SCLs exploit their partners when it comes to profitability.

Figure 4 summarizes the main results.

5.5. Financial Dependence of Suppliers in SCL Networks

Until now, the discussion has been focused on the fact that suppliers and customers gain similar financial advantages and disadvantages by doing business with SCLs. It was highlighted that the SCLs are the dominant firms that gain the most from the supply chain’s financial performance. Now, the discussion shifts to a closer look at the firms’ respective positions in the chain and the dependency of suppliers and customers of SCLs.

Looking more closely at the supply chain position of the firms in the three samples, whereas most SCLs (70.6%) and suppliers (85.7%) are manufacturers and so on, instead of one step before the point of consumption, the majority of customers (40.5%) are retailers and have direct contact with end consumers. Lanier et al. [

24] showed that downstream members have more profitability benefits. This contradicts the present study results on two points. First, the power in the suppliers–SCL and SCL–customers constellation lies in the middle, where SCLs have a dominant position and gain most from the profitability in the chain. Second, the customers, who are the most downstream members in this triad and are closest to the final consumer, do not display superior profitability ratios.

We already addressed that suppliers’ results, compared to the customers’ results, are much more statistically significant and clear. Now, these results will be deepened. In order to analyze the dependence of suppliers and customers of SCLs, the sample sizes (see

Appendix B) and the relationship strength are briefly examined.

Looking at the sample sizes, in terms of market capitalization and employee numbers, all SCL firms are at least large cap, and the majority of the firms (70.6%) have more than 100,000 employees. While the suppliers’ sample consists mainly of mid- (39.3%) and large (42.9%) caps, with only 21.4% of the firms that have more than 100,000 employees, 76.1% of the customer firms are at least large caps, and 61.9% have more than 100,000 employees. The SCLs are among the biggest and most powerful firms in the world, and the customer firms are, on average, bigger than the supplier companies. We suggest a higher dependency of suppliers on SCLs than customers. Kim and Henderson [

20] found differences between suppliers’ and customers’ resource dependency. Whereas the benefit of customer dependency for focal firms decreases after a while, the supplier dependency increases above this margin. In addition, if these results refer to the profitability of focal firms, they show that customers are less dependent on focal firms, which explains the decrease in performance. What is interesting here, is that the findings suggest that an increase in dependency is not only negative for supply chain members of SCLs but can also be positively correlated to financial performance. The suppliers’ results show better and more significant liquidity and activity ratios than customers’.

This discussion leads to the last proposition:

Proposition 5. Within an SCL’s network, suppliers benefit more than customers (leading to superior liquidity and activity ratios) but are also more exploited (leading to inferior profitability ratios).

Despite the clear results and the coherent proposition, several important points could not be answered:

Did the financial success, or rather failure, of the suppliers and customers already exist before they became members of the SCL’s network, or did this occur afterwards?

If the first of these applies, could this—the specific selection of suppliers respectively customers with superior liquidity and activity ratios respectively inferior profitability ratios—be a further success factor of SCLs?

Do the derived results also refer to smaller suppliers and customers of the SCL? In the present examination, only the biggest partners of the supply chain are examined.

The findings will probably not be transferable to the entire network and every single small player of the SCL. In that case, it would be interesting to know which type of supplier and customer is affected by this. Besides the company size according to COGS (suppliers) or revenue (customers), the criticality of the players could be of importance.

Besides the examined supply chain constellations, do further SCL networks exist, onto which the results could be transferred? Is it the criteria of the Gartner Supply Chain Top 25 rankings or other characteristics, which distinguish these SCL networks?

Which circumstances have to be met in order for not only the SCLs but also the suppliers and the customer firms of the network to have superior profitability ratios?