Approaches, Challenges, and Opportunities in Humanitarian Logistics Integrated with Reverse Logistics and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

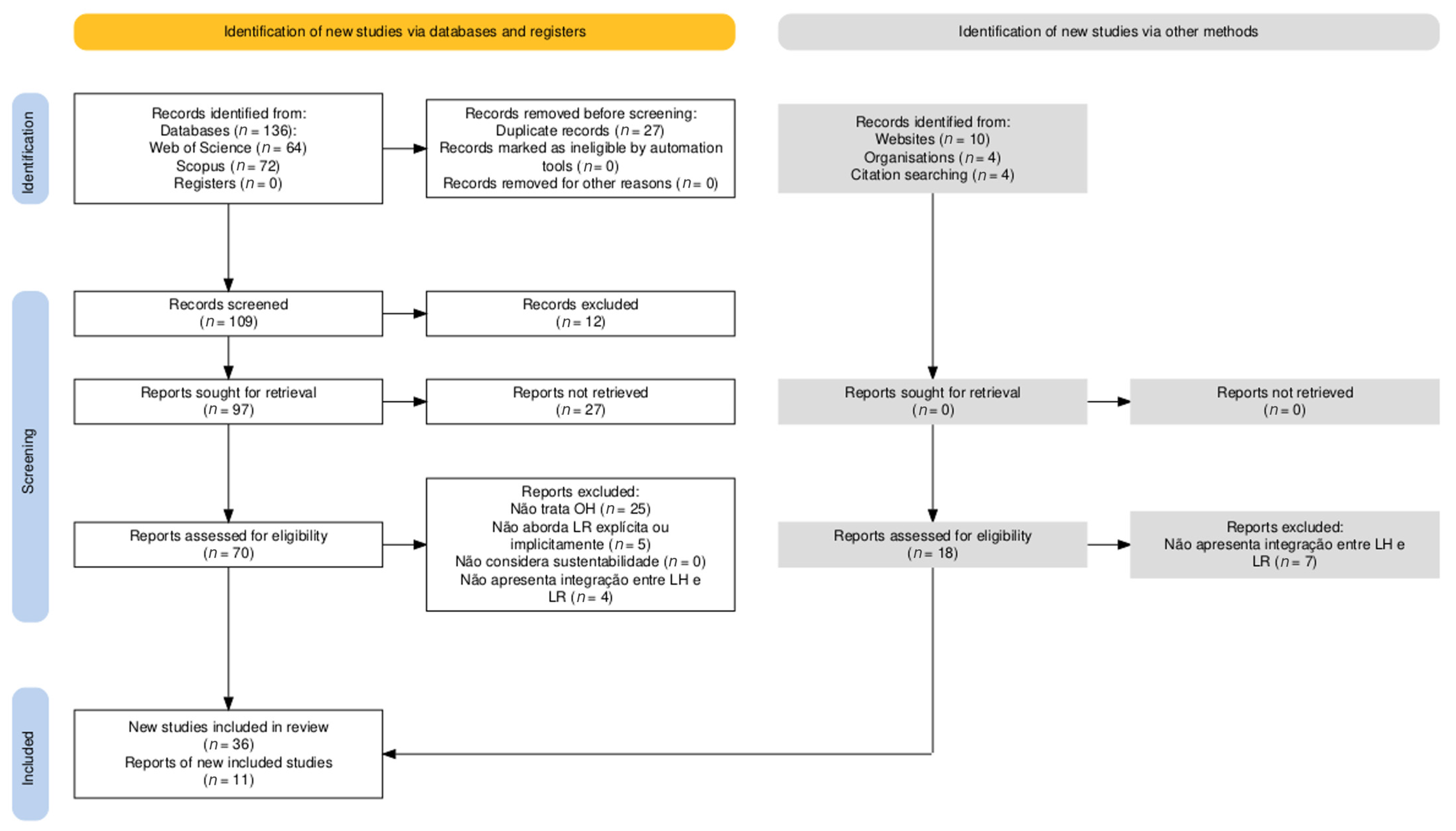

3. Materials and Methods

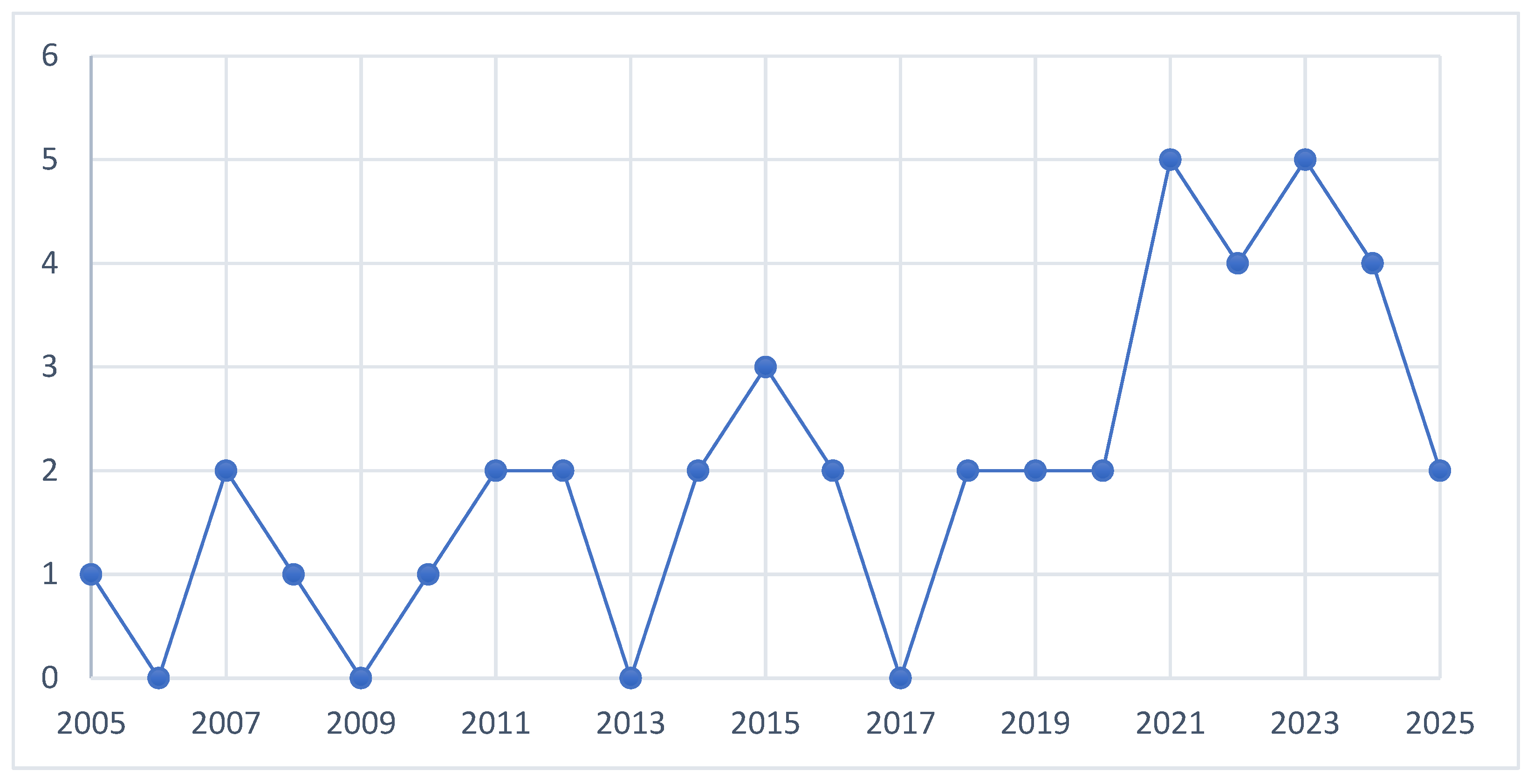

4. Results

- (i)

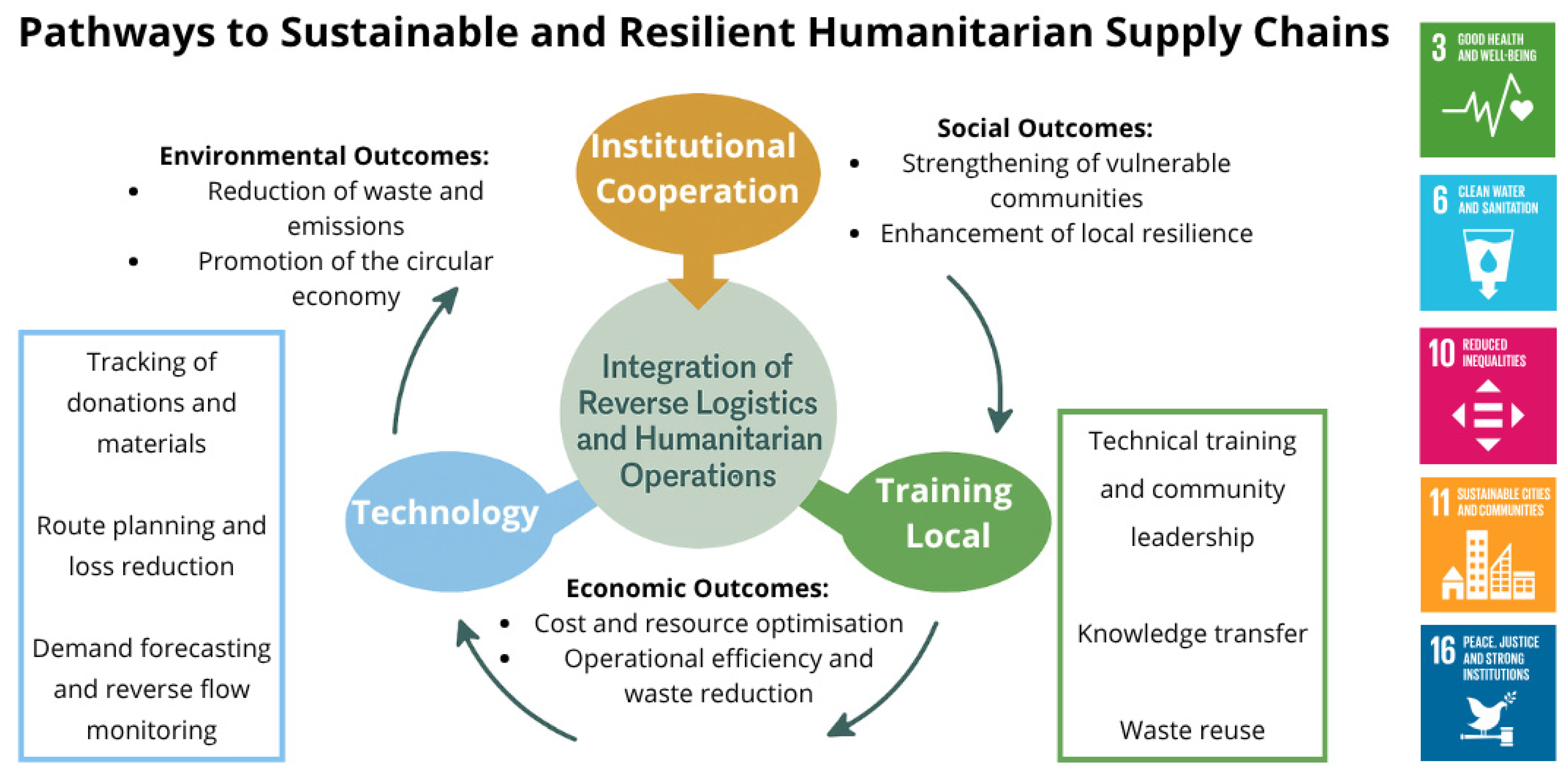

- Opportunities for circularity and sustainable waste management: Several studies demonstrate that RL enables recycling, reuse, energy recovery and the appropriate disposal of post-disaster waste, including construction debris, packaging, food waste and medical waste. These initiatives reduce environmental impacts, prevent contamination, and reintroduce materials into productive cycles, linking RL to the circular economy and SDG 12. Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies in disaster settings, for example, show that early planning of segregation and recycling strategies can significantly reduce emissions and end-of-life disposal costs.

- (ii)

- Opportunities to strengthen operational resilience: The literature indicates that, when planned, RL contributes to clearing access routes, freeing warehouse capacity, optimising inventories, and redesigning routes, thereby strengthening the response and recovery capacity of humanitarian supply chains. Pre-positioning models that incorporate returns, as well as systems for collecting inappropriate donations, exemplify how reverse flows can reduce uncertainty, mitigate risks, and support decision-making under pressure. Theoretically, such opportunities link RL and systems resilience, showing that structured reverse flows enhance flexibility and the ability of HOs to reorganise.

- (iii)

- Opportunities for sociotechnical innovation and digitalisation: Recent studies explore the use of blockchain for donation traceability, IoT and IoMT for monitoring inventories and medical waste, 3D printing for transforming plastic waste into useful inputs and multi-objective algorithms to optimise reverse routing and resource allocation. These initiatives are classified as opportunities for sociotechnical innovation, as they integrate emerging technologies, new governance arrangements, and RL practices oriented towards sustainability. Experiences with integrated digital platforms in humanitarian medical supply chains illustrate the potential to monitor returns in real time, reduce losses, and support data-driven decisions.

- (iv)

- Institutional opportunities and pathways for sustainability transitions: Finally, several studies highlight opportunities to incorporate RL into public policies, waste management regulations, donor guidelines, and socioenvironmental responsibility strategies of humanitarian organisations. Such initiatives create formal incentives for circular practices, enable the standardisation of procedures, and foster coordination among actors. In theoretical terms, these opportunities represent drivers of sustainability transitions, shifting RL from an occasional practice to a structural component of sustainable and resilient humanitarian supply chains.

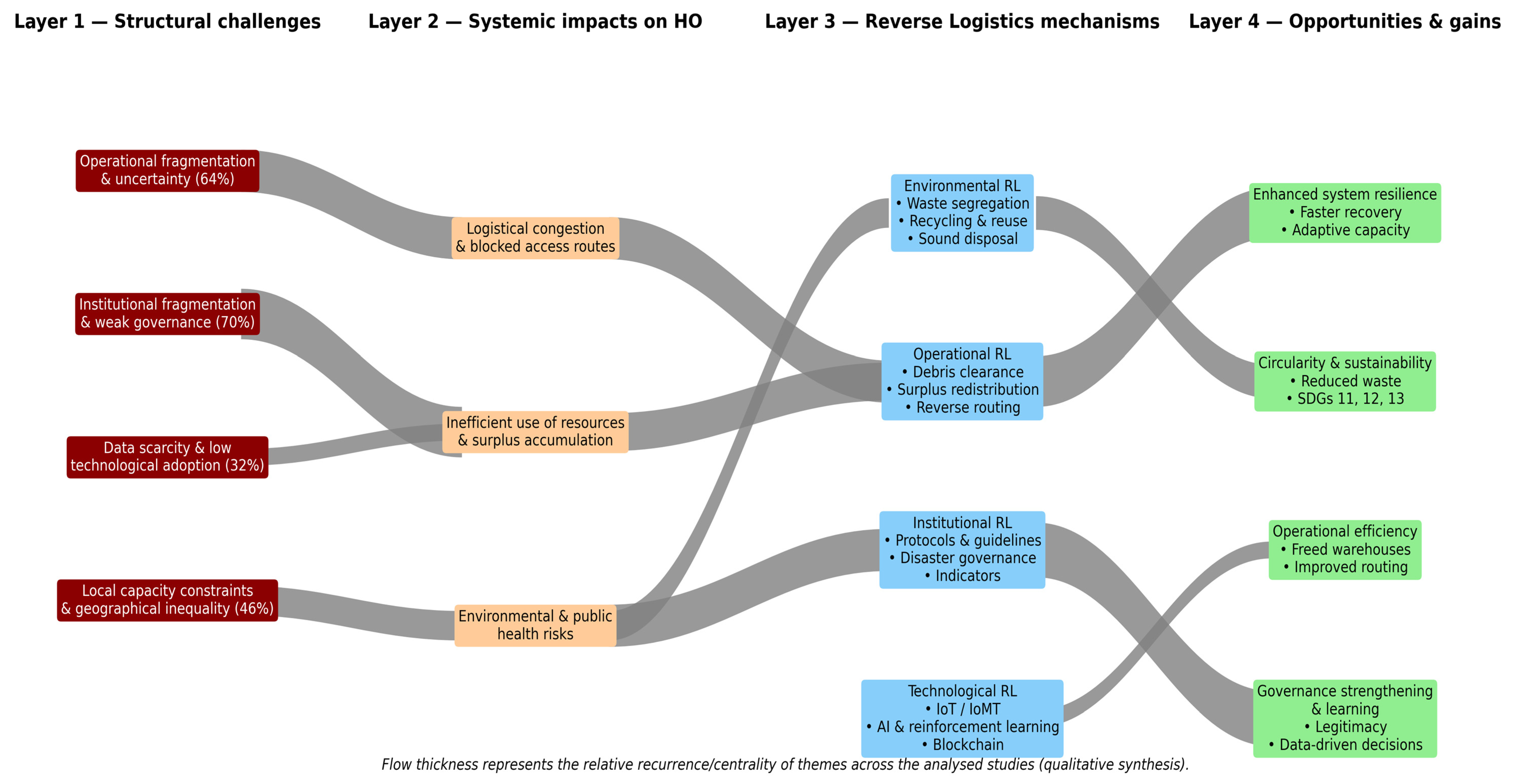

5. Discussion

- (i)

- Environmental mechanisms, such as waste segregation, recycling and reuse, and environmentally sound disposal;

- (ii)

- Operational mechanisms, including debris clearance, surplus redistribution, and reverse routing with stock release;

- (iii)

- Institutional mechanisms, comprising protocols and guidelines, integration into disaster governance, and the use of performance indicators;

- (iv)

- Technological mechanisms, involving IoT/IoMT, artificial intelligence and reinforcement learning, and blockchain-based traceability systems.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Detailed workflow—StArt software

- (1)

- Completion of the review protocol

- The research question: How is Reverse Logistics conceptualised, applied, and evaluated in the literature on Humanitarian Operations from a sustainability perspective?

- The specific objectives: to identify conceptualisations, applications by disaster type, methodological approaches, and integration with sustainability;

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria:Inclusion—(i) explicitly addressing Reverse Logistics (RL) applied to Humanitarian Operations (HOs); (ii) addressing practices conceptually aligned with RL, even without using the term, such as product recovery, supply returns, recycling or reuse, post-disaster waste management, and redistribution of surpluses; (iii) falling within the thematic scope of Humanitarian Logistics (HL), sustainability, and disaster waste; and (iv) being a peer-reviewed scientific article.Exclusion—(i) not addressing RL, either directly or indirectly; (ii) not dealing with disaster operations or Humanitarian Logistics; (iii) presenting metadata failures, inaccessibility, or illegibility; (iv) not being a peer-reviewed article (e.g., reports, editorials, conference abstracts, etc.); or (v) duplicates across databases.

- The databases used: Web of Science and Scopus;

- Keywords and synonyms: Reverse Logistics, returns management, closed-loop supply chain, reverse flows, end-of-life products, waste management, product recovery; humanitarian, disaster relief, emergency response, crisis management, relief supply chain, aid distribution, Humanitarian Operations; sustainability, sustainable development, resilience, circular economy, green logistics, environmental management; logística reversa, fluxos reversos, recuperação de materiais, reciclagem, reuso, redistribuição de doações, resíduos pós-desastre; logística humanitária, cadeia de suprimentos humanitária, resposta a desastres, ajuda humanitária; sustentabilidade ambiental, economia circular, logística verde, gestão ambiental, resiliência, ACV.

- Data fields to be extracted at the synthesis stage: bibliographic data; study type and methodology; disaster type; phase and context of HOs; conceptualisation and application of RL; role of RL (environmental/operational/institutional/technological); sustainability elements; technologies used; main results; challenges; opportunities; contributions; and limitations.

- (2)

- Definition of search strings for each database

- (“reverse logistic*” OR “returns management” OR “closed-loop supply chain*” OR “reverse flow*” OR “end-of-life product*” OR “waste management” OR “product recovery”)

- AND (“humanitarian” OR “disaster relief” OR “emergency response” OR “crisis management” OR “relief supply chain*” OR “aid distribution” OR “humanitarian operation*”)

- AND (“sustainability” OR “sustainable development” OR “resilience” OR “circular economy” OR “green logistic*” OR “environmental management”)

- (3)

- Execution of external searches and export of results

- (4)

- Import of BibTeX files into StArt

- Consolidated metadata;

- Recorded the source of each study (database/dataset);

- Stored the search string used;

- Generated the initial study database prior to screening.

- (5)

- Title and abstract screening using inclusion/exclusion criteria

- (6)

- Full-text reading of accepted studies

- Reclassification of studies;

- Reapplication of inclusion/exclusion criteria;

- Identification of potential quality issues;

- Insertion of reviewers’ comments.

- (7)

- Data extraction and collection of relevant information

- Bibliographic data;

- Objectives;

- Disaster type;

- Methodological approach;

- Framing of Reverse Logistics;

- Sustainability elements;

- Challenges and opportunities;

- Theoretical and practical contributions.

- (8)

- Reporting and synthesis of the selected studies

- Construction of the PRISMA flow diagram;

- Quantification of studies by category;

- Thematic coding;

- Qualitative analysis and integrative discussion.

Appendix B

| Journal | Methodology | Citations | Source |

| Resilience and Urban Risk Management | Systematic review | 6 | [6] |

| South Florida Journal of Development | Simulation | 64 | [22] |

| Environment’s Experiences and Approaches | Spatial regression, statistical modelling, and machine learning | 10 | [48] |

| Internacional Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistcs Managemente | Regression models, statistical sales analysis, and per capita income analysis | 14 | [49] |

| IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability | Multi-objective mathematical modelling and metaheuristics (MOSOA, among others) | 22 | [50] |

| Journal of Industrial Information Integration | Multi-objective mathematical model with dynamic simulation | 0 | [51] |

| Sustainable Qatar | Modelling | 33 | [52] |

| Supply Chain Analytics | Survey | 71 | [53] |

| Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management | Case study and optimised system modelling (simulation) | 4 | [54] |

| Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology | Network analysis in GIS (Geographic Information System) applied to post-disaster routing | 6 | [55] |

| Sustainability | System proposal and experimental prototyping | 32 | [56] |

| Production and Operations Management | Modelling | 43 | [57] |

| Transportation Research Part E | Methodological development for the analysis of dysfunctions in urban technical networks | 1 | [58] |

| Sustainability | Systematic review following PRISMA guidelines | 12 | [59] |

| Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias Del Aprendizaje | Survey | 2 | [60] |

| Cahiers des Amériques latines | Applied study with multi-criteria analysis and GIS | 7 | [61] |

| Journal Sustainable Production and Consumption | Bibliographic research | 0 | [62] |

| Vulnerability, Uncertainty, and Risk | Systemic functional analysis applied to a real waste-management chain | 24 | [63] |

| Logistics | Systematic literature review/multi-criteria decision analysis | 9 | [64] |

| Journal HumanFactors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service | Normative and institutional analysis (NCRP guidelines) | 2 | [65] |

| Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | Applied research, experimental design, and laboratory testing | 83 | [66] |

| International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering | Bibliographic research | 1 | [67] |

| IEEE Acess | Systematic Literature Review | 52 | [68] |

| Production and Operations Management | Normative, technical, and institutional analysis; review of guidelines and decision-making processes for post-radiological-event recovery | 3 | [69] |

| Health Physics | Comparative analysis between linear and adaptive management approaches; review of real cases | 16 | [70] |

| Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences | State-of-the-art review and experimental testing of solar stove prototypes manufactured from humanitarian supply packaging | 19 | [71] |

| Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management | Prototype development and laboratory testing | 6 | [72] |

| Sustainability | Applied research, prototyping, and laboratory testing | 35 | [73] |

| Sustainability | Survey | 13 | [74] |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Case study | 11 | [75] |

| Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management | Multi-objective mathematical modelling and metaheuristics | 9 | [76] |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) | 10 | [77] |

| Humanitarian Logistics and Sustainability | Multi-criteria decision analysis | 34 | [78] |

| Health Physics | Systematic Literature Review | 14 | [79] |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | Network analysis in GIS (Geographic Information System) applied to post-disaster routing | 1 | [80] |

| Computers and Industrial Engineering | Modelling | 4 | [81] |

| Sustainability | Case study | 47 | [83] |

| International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | Modelling | 179 | [84] |

| Sustainable Qatar: Social, Political, and Environmental Perspectives | Systematic Literature Review (PRISMA) | 2 | [85] |

| Sustainable Production and Consumption | Empirical study on consumer behaviour | 28 | [86] |

| Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management | Documentary and historical analysis of disasters over two decades, based on UN databases (UNISDR) and UNEP institutional experiences | 6 | [87] |

| Socio-Economic Planning Sciences | Bibliographic research | 58 | [88] |

| Post-Disaster Reconstruction of the Built Environment | Simulation | 32 | [89] |

| Risk Analysis | Survey | 4 | [90] |

| Benchmarking: An International Journal | Case study and modelling | 45 | [91] |

| Science of the Total Environment | Environmental monitoring study | 116 | [92] |

| International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | Systematic Literature Review | 170 | [93] |

| Waste Management and Research | Case study and modelling | 420 | [93] |

| Sanitary and Environmental Engineering | Simulation | 29 | [94] |

Appendix C

| Objective | Results | LR and LH Approaches | Source |

| To identify logistical criteria for the location of humanitarian centres and to assess multi-criteria decision-making methods applied to the optimisation of post-disaster supply. | The study shows that location decisions directly affect the efficiency and speed of humanitarian response, with a predominance of MCMD, mathematical programming, and heuristics, and highlights the need to incorporate uncertainty, social constraints, and environmental factors. | HL forms the core of the analysis through strategic supply positioning, while RL emerges in the recovery phase via post-disaster waste management, with humanitarian centres potentially acting as RL hubs to support reconstruction. | [6] |

| To examine the use of rapid prototyping in spare-parts supply chains within Humanitarian Operations. | Rapid prototyping increases resource availability and sustainability by reducing waste and optimising operational processes. | HL benefits from improved responsiveness and availability of critical components, while RL contributes through waste reduction and more efficient use of materials enabled by additive manufacturing. | [22] |

| To develop a Humanitarian Logistics framework to support post-COVID-19 economic reactivation based on spatial vulnerability patterns. | The study shows that higher COVID-19 mortality rates are strongly associated with population density and economic activity. Based on spatial modelling, the authors propose a framework to prioritise the distribution of essential goods and services according to vulnerability levels, demonstrating that spatially informed logistics decisions reduce social deprivation costs and improve recovery efficiency. | LH structures the emergency response and the prioritised distribution of essential goods during the pandemic, while LR is implicitly embedded in the rebalancing of disrupted productive flows and the reuse of idle logistics capacities during the recovery phase, supporting a more resilient and sustainable post-crisis supply system. | [48] |

| To analyse panic buying behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Panic buying was more pronounced in higher-income neighbourhoods, particularly for hygiene products and toilet paper, revealing inequities in access to essential goods during crises and exacerbating the vulnerability of lower-income populations. | RL is required to restore inventories and redistribute post-crisis surpluses, while HL plays a central role in ensuring equitable access to essential goods. | [49] |

| To develop an optimisation framework for emergency supply chains during pandemics, prioritising elderly populations while reducing costs, unmet demand, and environmental impacts. | The integrated model proved effective in prioritising high-risk groups, enhancing resilience, sustainability, and equity in resource allocation, while incorporating medical and recyclable waste management practices. | HL structures emergency supply chains for the distribution of PPE, medical supplies, and testing kits during pandemics, while RL integrates reverse flows through the management and recycling of medical and hospital waste. | [50] |

| To develop an optimisation framework for emergency supply chains during pandemics, prioritising elderly populations, reducing costs, minimising unmet demand, and lowering environmental impacts. | The integrated model proved effective in prioritising high-risk groups, ensuring greater resilience, sustainability, and equity in resource allocation. It also incorporated practices for the management of medical and recyclable waste. | Humanitarian Logistics (HL) structures the emergency supply chain for the distribution of PPE, medical supplies, and testing kits in pandemic contexts. Reverse Logistics (RL) supports the management and recycling of medical and hospital waste, integrating reverse flows into the optimisation model. | [51] |

| To identify, analyse, and prioritise key enablers of humanitarian supply chain management (HSCM) in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of Humanitarian Operations. | Using a hybrid decision-making framework combining Fuzzy Delphi, ISM-MICMAC, and the revised Simos method, the study identifies 28 enablers, of which 20 are prioritised. Government policy support and leadership emerge as the most influential enablers, exhibiting high driving power and low dependence. The results highlight the importance of coordination, collaboration, and governance for strengthening humanitarian supply chain performance. | The study is firmly positioned within Humanitarian Logistics (HL), focusing on coordination, governance and decision-making in disaster relief supply chains. Reverse Logistics (RL) is not explicitly modelled; however, the findings indirectly support sustainable and efficient humanitarian systems that can facilitate waste reduction and resource optimisation in post-disaster contexts. | [52] |

| To investigate sustainability within humanitarian medical supply chains. | The study identifies a strong association between sustainability challenges and humanitarian medical supply operations, highlighting structural barriers related to coordination, resource allocation, and waste generation in crisis contexts. | HL structures the distribution and availability of medical supplies during humanitarian response, while RL supports sustainability through the management, recovery, and reduction in medical waste and surplus materials across the supply chain. | [53] |

| To develop a sustainable operational management system for a non-profit organisation that collects and redistributes surplus food. | The system reduced food waste, increased redistributed volumes, lowered operational costs, and enhanced overall logistical efficiency. | HL structures the redistribution of surplus food to meet humanitarian needs, while RL supports sustainability through the recovery and reuse of excess food within collection, transport, and distribution processes. | [54] |

| To propose a method to reduce the overlap between disaster waste transport routes and critical service routes (rescue, evacuation, hospitals, and police) following flood events. | The method increased the average length of waste transport routes by 25.29% during the response phase and 9.80% during the recovery phase, while substantially reducing overlap with critical service routes by 47.49% and 55.57%, respectively, thereby improving operational coordination in post-flood contexts. | Integrated into Humanitarian Logistics, in the context of post-flood response and recovery. | [55] |

| To develop and test a domestic biodigester system integrated with a dry toilet for biogas production from human waste, targeting humanitarian camps and developing regions. | The small-scale prototype produced biogas with a methane content of 74%, meeting basic energy needs for cooking and lighting, and proved to be a low-cost, simple, and replicable solution for humanitarian settings. | The study is situated within HL through its focus on sanitation, waste management, and energy provision in refugee camps, while indirectly supporting sustainability and circular practices without explicitly framing RL. | [56] |

| To assess the impact of incorporating return flows into pre-disaster deployment strategies for predictable rapid-onset disasters. | Integrating returns improves deployment efficiency and inventory availability, enhancing responsiveness under demand uncertainty. | LH governs pre-positioning and emergency distribution, while LR is operationalised through planned return flows that strengthen preparedness and post-event recovery. | [57] |

| To develop a method for identifying operational failures in waste management networks before, during, and after flood events. | The study shows that waste management networks constitute a critical determinant of post-disaster recovery, given the visual, sanitary, and psychological impacts of accumulated waste. The absence of clear response protocols exacerbates social impacts, while strengthening network resilience significantly reduces urban recovery time. | RL is reinterpreted as a strategic instrument within HL to support territorial recovery and post-disaster reorganisation. | [58] |

| To map prioritisation models used in Humanitarian Logistics. | The review reveals a strong predominance of multi-criteria decision-making models applied to sudden-onset natural disasters, with limited consideration of sustainability and RL within decision-support frameworks. | The analysis focuses on HL decision-making models, with minimal integration of RL and sustainability considerations. | [59] |

| Desenvolver uma rede de cadeia de suprimentos de alívio em pandemias, sustentável, resiliente e energeticamente eficiente, apoiada por IoMT. | The multi-objective model considered costs, ecological footprint, energy consumption, and unmet demand, demonstrating that IoMT enhances real-time decision-making and that energy efficiency strengthens sustainability and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. | RL is incorporated through reverse flows of medical waste, both recyclable and non-recyclable, while HL coordinates the distribution of essential supplies during pandemics, supported by IoMT-enabled rapid and effective decision-making. | [60] |

| To identify suitable locations for temporary disaster waste storage areas based on environmental, social, and technical criteria. | Eighteen candidate sites were identified in Cavite, demonstrating that planned temporary storage can reduce environmental risks, enable material recovery, and improve disaster response effectiveness. | HL is addressed through disaster waste management operations, with sustainability supported via recycling and material reuse, while RL is not explicitly conceptualised. | [61] |

| To outline and compare key characteristics of HL and RL in disaster contexts. | The study highlights the effective integration of RL and HL as a critical enabler of disaster response. | RL plays a central role in enhancing sustainability in disasters, complementing HL response mechanisms. | [62] |

| To assess how the resilience of waste management systems influences urban recovery capacity following flood events. | The study demonstrates that disruptions in waste management chains after flooding directly compromise urban recovery, amplifying sanitary, environmental, and social risks. Functional analysis identifies critical failures in pre-collection, transport, and final disposal, showing that waste logistics fragility is a structural driver of urban vulnerability. | Reverse Logistics (RL) operates as a mechanism for reorganising post-crisis waste flows, providing direct support to Humanitarian Logistics (HL) in the restoration of essential services. | [63] |

| To examine how optimisation models in Humanitarian Logistics incorporate real-world conditions, environmental concerns, and decision-maker involvement in order to support implementation. | The review finds limited practical engagement and implementation readiness: Only 10% of the analysed studies involved practitioners in model development, fewer than 22% proposed new solution methods capable of delivering timely results, and environmental considerations remain underrepresented despite the global relevance of sustainability. | The analysis focuses on HL through optimisation models for disaster operations, emphasising practical decision-making, efficiency, and sustainability, while RL is not addressed. | [64] |

| To strengthen decision-making processes during the late recovery phase of nuclear disasters. | The study highlights stakeholder participation as a key factor in defining effective strategies for cleanup, waste disposal, and territorial reoccupation, showing that participatory governance reduces social conflict and increases acceptance of technical decisions. | RL supports safe waste disposal and environmental recovery, while HL structures the transition from emergency response to normality during the recovery phase. | [65] |

| Reduce the environmental impact of packaging disposal in HOs while generating useful solutions for affected populations. | Prototypes created from packaging waste (rucksack, crib, sandals, and bench) were tested and proved resistant and applicable for refugees. | Integrates sustainability into HL through reuse and recycling of packaging materials; applies RL practices in humanitarian contexts. | [66] |

| To assess sustainability-related problems in disaster operations and examine how sustainable network structures can be strengthened. | The study highlights the importance of pilot initiatives and experimental trials as mechanisms for structuring more sustainable disaster response networks, supporting long-term operational viability. | Humanitarian Logistics (HL) frames disaster response and recovery operations, while Reverse Logistics (RL) contributes to sustainability by supporting waste management, resource recovery, and the reduction in environmental impacts in disaster management contexts. | [67] |

| To conduct a Systematic Literature Review on disaster healthcare supply chains, identifying challenges, emerging themes, and research opportunities. | The review identifies 14 core themes within disaster healthcare supply chains, including logistics operations, network design, resilience, preparedness, and waste management, while highlighting gaps related to leadership, corporate social responsibility, and sustainability. | The study emphasises Humanitarian Logistics (HL), with discussions on sustainability through waste management and corporate social responsibility; Reverse Logistics (RL) is not addressed. | [68] |

| To provide practical guidelines to support decision-making during the intermediate and late recovery phases following a radiological incident, with emphasis on communication, governance, and protection criteria. | The study highlights that post-radiological recovery decisions are characterised by technical uncertainty, social tension, and intense public scrutiny, underscoring the need for clear exposure criteria, transparent risk communication, and effective inter-agency coordination. | RL is expressed through the management of contaminated waste, decontamination, and environmental restoration, while HL focuses on sheltering, relocation, risk communication, and immediate protection during recovery phases. | [69] |

| To propose the use of adaptive management for the recovery of public facilities following chemical, biological, or radiological attacks, emphasising uncertainty and the need for continuous evaluation cycles. | The study demonstrates that linear response models are insufficient in contexts characterised by uncertainty, data scarcity, multiple stakeholders, and high operational complexity. Adaptive management enables flexible and iterative decision-making, reduces risks, enhances recovery agility, and strengthens public trust. | RL operates through the removal, transport, and disposal of hazardous waste, while HL focuses on immediate protection, evacuation, inter-agency coordination, and risk communication, with their integration becoming critical during the recovery phase when waste management directly affects response effectiveness. | [70] |

| To develop and validate a methodological framework for assessing municipal solid waste management systems in contexts of armed conflict, with the aim of improving the effectiveness, robustness, and sustainability of humanitarian response. | The methodology enabled a comprehensive assessment of waste management under armed conflict, identifying critical bottlenecks in collection, disposal, and recovery processes, as well as feasible pathways to improve system effectiveness under chronic emergency conditions. | HL is reflected in the organisation of essential waste management services to support humanitarian response and public health, while RL is implicitly incorporated through the recovery, redirection, and management of waste flows during post-crisis recovery. | [71] |

| Reduce the environmental impact of packaging disposal in humanitarian operations while simultaneously providing useful solutions for people affected by disasters. | Prototypes created from packaging waste (backpack, crib, flip-flops, and stool) were tested and demonstrated resistance and applicability for refugees. | Integration of sustainability into humanitarian logistics through the reuse and recycling of packaging materials; RL practices adapted to the humanitarian context. | [72] |

| Reduce the environmental impact of packaging disposal in HOs while generating useful solutions for affected populations. | Prototypes created from packaging waste (rucksack, crib, sandals, and bench) were tested and proved resistant and applicable for refugees. | Integrates sustainability into HL through reuse and recycling of packaging materials; applies RL practices in humanitarian contexts. | [73] |

| To classify technical requirements and operational solutions for waste management in refugee camps, aiming to improve environmental performance and operational effectiveness. | The study identifies key technical and organisational requirements for waste handling in refugee camps, highlighting the need for structured collection, separation, storage, and treatment systems. The results show that inadequate waste management compromises health, safety, and operational continuity in humanitarian settings. | Humanitarian Logistics (HL) frames the operational context of refugee camps and service provision. Reverse Logistics (RL) supports waste segregation, reuse, recycling, and disposal processes, functioning as a critical enabler of sustainable Humanitarian Operations. | [74] |

| To evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) fund policy in China and its contribution to environmental governance. | The study demonstrates that the WEEE fund policy has improved formal recycling rates and strengthened regulatory compliance, although challenges remain related to enforcement, regional disparities, and informal sector integration. | Reverse Logistics (RL) is central, structuring collection, treatment, and recycling flows for electronic waste. Humanitarian Logistics (HL) is indirectly supported by improved waste governance, which enhances system resilience and environmental safety in crisis-prone and high-risk urban contexts. | [75] |

| To develop a methodology for analysing dysfunctions in waste management networks before, during, and after flood events in order to improve territorial resilience. | The proposed methodology identifies critical failures across pre-collection, transport, and disposal stages. The findings show that waste management networks are among the most vulnerable urban systems during floods, and that their failure significantly delays recovery. | Reverse Logistics (RL) reorganises post-disaster waste flows and supports debris management and environmental recovery. Humanitarian Logistics (HL) relies on these reverse flows to restore essential services and enable safe and effective post-flood response. | [76] |

| To reduce the environmental impact of packaging disposal in Humanitarian Operations while simultaneously generating useful solutions for disaster-affected populations. | Prototypes developed from packaging waste—including backpacks, cribs, sandals, and benches—were tested and demonstrated durability and practical applicability for refugee contexts. | Sustainability is integrated into HL through the reuse and recycling of packaging materials, with RL practices adapted to humanitarian contexts to transform waste into functional resources. | [77] |

| To investigate how Humanitarian Logistics optimisation models incorporate real conditions, environmental concerns and decision-maker involvement to enhance implementation. | Only 10% of models involve practitioners; fewer than 22% provide timely solutions; environmental objectives are rarely included despite global sustainability priorities. | HL is the analytical core, focusing on optimisation for disaster response; LR is largely absent, revealing a structural gap in integrating waste, recovery flows and sustainability into decision-making models. | [78] |

| To conduct a Systematic Literature Review on disaster healthcare supply chains, identifying challenges, emerging themes, and research opportunities. | The review identifies 14 core themes—such as logistics operations, network design, resilience, preparedness, and waste management—while highlighting gaps related to leadership, corporate social responsibility, and sustainability. | Emphasis on Humanitarian Logistics, with discussion on sustainability in waste management and corporate social responsibility. | [79] |

| To propose a method to reduce the overlap between disaster waste transport routes and critical service routes (rescue, evacuation, hospitals, and police) following flood events. | The method increased average waste transport route length by 25.29% in the response phase and 9.80% in the recovery phase, while reducing overlap with critical service routes by 47.49% and 55.57%, respectively. | Integrated within Humanitarian Logistics, in the context of post-flood response and recovery. | [80] |

| To develop a model to control medicine surplus in Humanitarian Operations. | The study proposes a managerial model aimed at maintaining appropriate medicine quantities and reducing excess. | RL is emphasised as a mechanism to minimise financial losses and environmental harm associated with medicine surplus, while HL provides the operational context for managing medical supplies in humanitarian settings. | [81] |

| To analyse RL systems in Xiamen and their implications for human development. | The findings indicate that the expansion of RL contributes positively to human development outcomes in China. | RL is examined as a mechanism supporting human development in crisis scenarios, while HL is not explicitly addressed. | [83] |

| Explore enabling factors in humanitarian su-pply chain management. | Government policy as a facilitator of supply chain management. | Sustainability and RL in the efficient management of HOs. | [84] |

| To review and classify vehicle routing models applied to humanitarian supply chains. | The review identifies 94 relevant publications published between 2005 and 2022, categorised across 15 dimensions, including disaster types, objective functions, solution methods, modelling approaches, and disaster phases. | The analysis is centred on HL, with no explicit consideration of RL within the reviewed routing models. | [85] |

| To analyse consumer behaviour towards electronic waste from a sustainable development perspective, comparing developed and developing countries. | The study reveals significant differences in awareness, disposal behaviour, and recycling practices between contexts, highlighting behavioural and institutional barriers to effective e-waste management. | Reverse Logistics (RL) is addressed through consumer participation in collection and recycling systems for electronic waste. Humanitarian Logistics (HL) is indirectly connected, as improved e-waste systems strengthen environmental sustainability and resource availability in regions vulnerable to socioenvironmental crises. | [86] |

| To integrate disaster waste management as a structural component of Humanitarian Logistics and disaster risk reduction. | The study demonstrates that disaster waste constitutes a major barrier to humanitarian response, adversely affecting rescue operations, public health, environmental conditions, and reconstruction, particularly in the absence of prior planning. | RL operates through the recovery, separation, recycling, and final disposal of disaster waste, providing structural support to HL during post-disaster recovery processes. | [87] |

| The study shows that higher COVID-19 mortality rates are associated with high population density and intense economic activity. Based on this relationship, a spatially informed model was developed to guide the distribution of essential goods and services according to vulnerability levels, demonstrating that model-based logistical decisions can reduce social deprivation costs. | The study shows that higher COVID-19 mortality rates are associated with high population density and intense economic activity. Based on this relationship, a spatially informed model was developed to guide the distribution of essential goods and services according to vulnerability levels, demonstrating that model-based logistical decisions can reduce social deprivation costs. | RL supports the rebalancing of productive flows and the reuse of disrupted logistical capacities, while HL structures emergency response and the distribution of essential goods during crisis recovery. | [88] |

| Design and simulate a supply chain network for disaster relief operations in Japan. | A supply chain network model incorporating critical factors was proposed, simulated, and assessed, identifying bottlenecks and inefficiencies within the network. | RL is evidenced as the efficient and effective implementation and control of the flow of goods and services directly influence the ability to meet the needs of disaster victims. | [89] |

| To identify the key initiators and motives that drive cooperation among actors in humanitarian supply chains. | The study shows that cooperation in humanitarian supply chains is primarily driven by operational necessity, resource scarcity, and the need to improve effectiveness under uncertainty. Trust, information sharing, and coordination mechanisms emerge as central enablers, while organisational misalignment and limited transparency act as barriers to sustained collaboration. | Humanitarian Logistics (HL) constitutes the core analytical context, focusing on coordination and collaboration among humanitarian actors during disaster response and recovery. Reverse Logistics (RL) is indirectly connected through cooperative mechanisms that enable the redistribution of surplus resources, the return of unused materials, and the coordination of waste and recovery flows, contributing to more sustainable and resilient humanitarian supply chains. | [90] |

| To improve post-disaster procurement through a mixed procurement model combining spot markets and reverse auctions. | The two-period model captures demand uncertainty, improves responsiveness and provides managerial insights for relief procurement decisions. | LH structures emergency procurement and prioritisation of relief items; RL is explicitly operationalised through reverse auctions, enabling efficient post-disaster sourcing and recovery of supply capacity. | [91] |

| To detect and analyse the presence and spatial variation of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material along sewer networks surrounding COVID-19 isolation centres. | The study confirms the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and reveals spatial variations along the sewer network, demonstrating the feasibility of wastewater-based epidemiology as an early warning and monitoring tool during pandemics. | Reverse Logistics (RL) is indirectly related through the management, monitoring, and treatment of waste and wastewater streams. Humanitarian Logistics (HL) is supported by improved public health surveillance, enabling more informed decision-making in pandemic response and emergency health operations. | [92] |

| To analyse collaborative inventory strategies to mitigate stockout risks in healthcare supply chains during pandemics. | Collaborative approaches improve inventory visibility, reduce shortages, and enhance resilience under pandemic disruptions. | LH structures emergency healthcare supply chains, while LR contributes indirectly through inventory recovery, redistribution, and surplus management to stabilise supply. | [93] |

| To develop a model for defining and assessing supply chain agility based on Humanitarian Logistics experience. | Agility dimensions are identified as critical to rapid response, coordination, and adaptability in crisis contexts. | LH provides the empirical foundation for agile response, while LR is indirectly linked through post-crisis reconfiguration and recovery of disrupted supply chains. | [93] |

| To improve transportation procurement decisions in Humanitarian Operations through data-driven detection of abnormally low bids. | The proposed method enhances transparency, reduces opportunistic behaviour, and improves procurement efficiency. | LH frames procurement and transport contracting in emergencies; LR relates conceptually to sustainability and efficiency gains through better allocation of transport resources. | [94] |

Appendix D

| General Block of Challenges | Detailed Description of the Identified Challenge | References |

|---|---|---|

| Operational and system resilience | Sectoral resistance and cultural barriers to the adoption of RL practices (inadequate donations, resistance to reuse, and limited social acceptance). | [22,53,73,86] |

| Sustainable management and disposal of medical waste in emergency and pandemic contexts. | [50,51,53,79,91] | |

| Ensuring equity in access to essential goods during crises, avoiding shortages and waste. | [48,49,50,68,83] | |

| Low level of RL maturity in humanitarian supply chains and scarcity of operational frameworks. | [22,59,64,85] | |

| Misalignment between academic models and practical needs; limited involvement of decision-makers. | [22,52,64,87] | |

| Management of large volumes of heterogeneous post-flood waste, with risks of secondary pollution. | [55,58,61,63,93] | |

| Difficulty in consistently measuring and applying agility in humanitarian supply chains. | [64,78,87,90] | |

| Management of organic waste and sanitation limitations in refugee camps. | [56,66,71,72] | |

| Management of large volumes of packaging waste and technical limitations to reuse. | [56,71,72,73] | |

| Limitations in the practical application of life cycle assessment (LCA) in disaster contexts due to time pressure and data constraints. | [26,59,66,91] | |

| Institutional and governance-related | Difficulty in translating public policies into effective and sustainable HL operational actions. | [35,52,65,69] |

| Absence of studies linking the environmental impacts of stockouts to RL and HL practices. | [48,49,57,68] | |

| Need to expand RL systems in human development contexts. | [22,53,54,75] | |

| Lack of role clarity and diffuse responsibilities among humanitarian actors. | [22,31,36,52] | |

| Weak integration of sustainability in disaster operations and lack of practical trials. | [9,53,59,85] | |

| Challenges in the effective integration of RL and HL in large-scale operations. | [22,24,64,76] | |

| Insufficient incorporation of the recovery phase into local and state-level plans. | [6,20,57,63] | |

| Pandemics and global systemic shocks | Uncertainty in demand and supply capacity during pandemics; limited integration of forward and reverse flows. | [48,50,51,68,79] |

| Vulnerability of global supply chains exposed during pandemic crises. | [48,68,79,83] | |

| Scalability and reliability limitations of rapid prototyping solutions. | [22,71,72,73] | |

| Procurement, donations, and circularity | Inefficiencies in procurement and storage processes in post-conflict contexts. | [75,81,90,94] |

| Lack of in-depth analyses linking sustainable supply chains to RL in HOs. | [22,59,64,85] | |

| Barriers to sustainability in humanitarian medical supply chains, particularly regarding medicine donations. | [50,53,79,91] | |

| Difficulties in forecasting resource reuse and the costs associated with returns in pre-disaster phases. | [57,64,76,80] | |

| Limitations in textile reuse within humanitarian NGOs. | [22,73,74,86] | |

| Infrastructure, waste, and environmental risks | Definition of robust criteria for humanitarian warehouse siting integrating RL considerations. | [6,61,64,77] |

| Absence of specific guidelines for disaster waste management. | [58,63,65,69] | |

| Excessive dependence on donations and misalignment between food supply and demand. | [49,54,73,86] | |

| Armed conflicts and economic blockades limiting access to essential materials. | [66,69,75,87] | |

| Low capacity for oily waste management following accidents. | [70,91,93] | |

| Challenges in integrating disaster waste transport with essential services. | [55,58,63,93] | |

| Technologies, data, and local capacities | Technical and energy-related limitations of innovative solutions in remote locations. | [56,66,71,72] |

| Heterogeneity of mortality records undermining HL proposals. | [48,68,83,91] | |

| Excessive reliance on landfilling for post-disaster waste. | [58,63,93] | |

| Cost and privacy barriers to the adoption of emerging technologies. | [38,39,68,80] | |

| Scarcity of tactical-level studies (e.g., inventory management). | [22,64,76,90] |

| General Block of Opportunities | Detailed Description of the Identified Opportunity | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Governance, public policies, and institutionalisation | Use disasters as a trigger to accelerate the compliance of cities and communities with the National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) through the implementation of permanent collection and recycling networks. | [6,93] |

| Establish cooperative mechanisms with incentives for HL providers and the sharing of penalties and fees, activating reverse flows and international redistribution prior to product expiration. | [50,92] | |

| Integrate RL practices into institutional enablers such as governance structures, inter-organisational collaboration, and digital technologies. | [62,63] | |

| Establish integrated command and control centres to support rapid and coordinated decision-making in humanitarian crises. | [59] | |

| Operational and system resilience | Apply RL practices for the reuse and recovery of medical equipment and personal protective equipment (PPE), reducing environmental impacts and enhancing sustainability in HOs. | [48,68,69] |

| Integrate planning and inventory management mechanisms across humanitarian and consumer supply chains, promoting equity of access, and reducing waste. | [49,60] | |

| Strengthen post-flood waste management with a focus on urban resilience, material recovery, and integration with public health and urban planning. | [52,53,79,83] | |

| Minimise environmental impacts in humanitarian supply chains through the integration of forward and reverse flows and the use of advanced analytical tools. | [54,58,72,91] | |

| Reuse resources and plan operations based on integrated forward and reverse flows, reducing costs, and environmental impacts. | [66,74] | |

| Develop sustainable emergency supply chains by integrating forward and reverse flows, using stochastic and dynamic modelling to enhance resilience and equity. | [68,69] | |

| Increase agility in disaster control in large cities through the integration of logistical planning with RL practices. | [77,78] | |

| Circularity, waste and environmental sustainability | Produce clean energy (biogas) from human waste in emergency contexts; reuse waste as fertiliser; reduce sanitary and environmental risks; and contribute to the SDGs (health, sanitation, and clean energy). | [55] |

| Transform packaging waste into useful resources for displaced populations, reducing environmental impacts, and disposal costs. | [56,57] | |

| Explore innovative strategies for RL of Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste in post-disaster contexts, promoting sustainability, and resilience. | [88,89] | |

| Transform hazardous waste (such as oil spills and plastics) into useful resources, reducing environmental impacts. | [82,84] | |

| Technologies, data, and sociotechnical innovation | Introduce environmental and sustainability criteria into HL models; expand practitioner involvement; develop heuristics and metaheuristics to reduce solution time; and align academic objectives with practical priorities. | [51,87] |

| Explore sustainability as a strategic factor in humanitarian medical supply chains; advance research on waste management and corporate social responsibility; and use digital and analytical technologies to reduce losses. | [64,65] | |

| Use digital technologies and the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) for real-time data collection and analysis, integrating sustainability and operational efficiency. | [69,90] | |

| Optimise procurement and storage processes in Humanitarian Operations, making them more agile and sustainable. | [71] | |

| Promote transparency in procurement and transport, strengthening trust and efficiency in relief operations. | [73] | |

| Improve the operational management of humanitarian supply chains with a focus on sustainability and waste reduction. | [75,80,85] | |

| Human development, equity, and territorial planning | Apply Spatial Dependence Models (SDMs) to estimate regional vulnerabilities and support the integration of HL and human development. | [61] |

| Promote human development through RL by adding value to reuse and recovery processes in crisis contexts. | [70,76] | |

| Support public health policy planning through the integration of mortality data and HL. | [86] |

- Ref. [9]—Predominantly conceptual and normative, focused on sustainability agendas (e.g., SDGs), providing theoretical grounding rather than operational propositions.

- Ref. [22]—Foundational and diagnostic study that systematises challenges and barriers in RL and HOs, serving as a conceptual backbone rather than a source of specific opportunities.

- Ref. [67]—Highly descriptive and context-specific, contributing empirical diagnosis without formulating actionable or transferable opportunities.

- Ref. [81]—Focused on analytical assessment of procurement/storage issues, informing problem identification rather than proposing improvement strategies.

- Ref. [94]—Addresses procurement efficiency and risk detection through a technical data-driven approach, supporting challenges analysis but not directly formulating sustainability- or RL-oriented opportunities.

- Accordingly, the absence of these references reflects their diagnostic, conceptual, or highly specific nature, which informed the synthesis but did not yield explicit opportunity statements suitable for inclusion in the table.

Appendix E

| Words | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | Total Number of Terms Per Article |

| Source | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| 21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 37 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||

| 38 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 40 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 41 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 42 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 43 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 47 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 48 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| 50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 52 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| 54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 55 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 56 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 57 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 58 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 61 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 63 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 64 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 65 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 66 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 68 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 69 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 71 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 72 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 73 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 74 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| 75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 76 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 77 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 78 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 79 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 81 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 82 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 83 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 84 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 41 | 37 | 34 | 32 | 30 | 27 | 12 | 26 | 26 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 29 | 10 | ||

| Note: (a) Humanitarian Logistics; (b) transportation; (c) humanitarian supply chain; d() disaster; (e) Humanitarian Operations; (f) supply chain management; (g) operational costs; (h) Reverse Logistics; (i) sustainability; (j) environmental management; (k) critical success factors; (l) donations; (m) location; and (n) life cycle assessment. | |||||||||||||||

References

- Instituto Brasil Logística. Guia de Logística Humanitária; IBL: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, G.; Spens, K. Identifying challenges in humanitarian logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecken, A. Logistics in the Context of Humanitarian Operations. In Advanced Manufacturing and Sustainable Logistics; Dangelmaier, W., Blecken, A., Delius, R., Klöpfer, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 46, pp. 85–93. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-12494-5_8 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Cunha, L.R.A.; Leiras, A.; Goncalves, P. Looking back and beyond the complex dynamics of humanitarian operations. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 14, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L.R.A.; Antunes, B.B.P.; Rodrigues, V.P.; Ceryno, P.S.; Leiras, A. Measuring the impact of donations at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP) amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 335, 1209–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scatolini, F.; Bandeira, R.A.D.M. Desastres como oportunidade de implementação de políticas de gerenciamento de resíduos de construção e demolição no Brasil: Chuvas de Nova Friburgo (RJ), 2011. Eng. Sanit. E Ambient. 2020, 25, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.R.; Council of Logistics Management. Reverse Logistics: White Paper; Council of Logistics Management: Lombard, IL, USA, 1992; Available online: https://books.google.com.br/books?id=XqiWGAAACAAJ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Rogers, D.S.; Tibben-Lembke, R.S. Going Backwards: Reverse Logistics Trends and Practices; Reverse Logistics Executive Council: Reno, NV, USA, 1999; 280p. [Google Scholar]

- Coffman, M.; Noy, I. Hurricane Iniki: Measuring the long-term economic impact of a natural disaster using synthetic control. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2012, 17, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Foropon, C.R.H. Improving information alignment and coordination in humanitarian supply chain through blockchain technology. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Veras, J.; Taniguchi, E.; Jaller, M.; Aros-Vera, F.; Ferreira, F.; Thompson, R.G. The Tohoku disasters: Chief lessons concerning the post disaster humanitarian logistics response and policy implications. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2014, 69, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldera, S.; Jayarathna, C.; Desha, C. Evaluating the Characteristics of Disaster Waste Management in Practice: Case Studies from Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, R.E.; Hall, D.; Hanna, J.B.; Kelly Rainer, R. Research in humanitarian logistics. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 1, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian aid logistics: Supply chain management in high gear. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshed, M. Standardizing Six Sigma Green Belt training: Identification of the most frequently used measure phase DMAIC tools. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2022, 13, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, B.M.; Balcik, B. Performance measurement in humanitarian relief chains. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2008, 21, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, P.H.; Pettit, S.J. Transforming humanitarian logistics: The journey to supply network management. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, N.; Gold, S. Sustainable humanitarian supply chain management–exploring new theory. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2017, 20, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontainha, T.C.; Leiras, A.; Bandeira, R.A.D.M.; Scavarda, L.F. Public-Private-People Relationship Stakeholder Model for disaster and humanitarian operations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C.J.; Pedraza-Martinez, A.J.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable humanitarian operations: An integrated perspective. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 4393–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Parvaiz, G.S.; Tohirovich Dedahanov, A.; Iqbal, M.; Junghan, B. Research trends in humanitarian logistics and sustainable development: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2143071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti, U.; Tatham, P.; Wu, Y.; Sgarbossa, F. Reverse logistics in humanitarian operations: Challenges and opportunities. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 5, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, D. The barriers to environmental sustainability in post-disaster settings: A case study of transitional shelter implementation in Haiti. Disasters 2025, 38, S25–S49. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/disa.12054 (accessed on 11 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.H.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ronchi, S. On the role of regional hubs in the environmental sustainability of humanitarian supply chains. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Olsen, T.; Ganguly, S.; Liu, Y. Food supply chain waste reduction for a circular economy in the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study of New Zealand consumers. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 800–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A.J.; Phillips, P.S. Biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) management strategy in Ireland: A comparison with some key issues in the BMW strategy being adopted in England. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 49, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokka, L.; Antikainen, R.; Kauppi, P.E. Municipal solid waste production and composition in Finland—Changes in the period 1960–2002 and prospects until 2020. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 50, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Swanson, R.; Smith, R.J. A Path to a Public–Private Partnership: Commercial Logistics Concepts Applied to Disaster Response. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Cao, C.; Liu, Y.; Qu, T. Organizational coordination in sustainable humanitarian supply chain: An evolutionary game approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna-Salvadó, L.; Lauras, M.; Okongwu, U.; Comes, T. A multicriteria Master Planning DSS for a sustainable humanitarian supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 1303–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, G.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, B.; Schnoor, J.L. Extended producer responsibility system in China improves e-waste recycling: Government policies, enterprise, and public awareness. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. In Advances in Strategic Managemen; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2000; pp. 143–166. Available online: http://www.emerald.com/books/edited-volume/14074/chapter/84962949 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- King, D. Becoming Business-Like: Governing the Nonprofit Professional. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect Q. 2017, 46, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.; Camenforte, R.A.; Duldulao, L. Robust packaging solutions through innovative designs in clip-QFN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 17th Electronics Packaging and Technology Conference (EPTC), Singapore, 2–4 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–3. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7412291/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Yılmaz, Ö.F.; Yeni, F.B.; Gürsoy Yılmaz, B.; Özçelik, G. An optimization-based methodology equipped with lean tools to strengthen medical supply chain resilience during a pandemic: A case study from Turkey. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 173, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning Series; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; 526p. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Yang, H.; Shang, H. Reinforcement learning approach for resource allocation in humanitarian logistics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 173, 114663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, B.; Rabadi, G. Optimizing Humanitarian Logistics with Deep Reinforcement Learning and Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Modeling and Simulation Conference (ANNSIM), Washington, DC, USA, 20–23 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–13. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10732882/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Agrawal, S.; Oza, P.; Kakkar, R.; Tanwar, S.; Jetani, V.; Undhad, J.; Singh, A. Analysis and recommendation system-based on PRISMA checklist to write systematic review. Assess. Writ. 2024, 61, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Bennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, E.; Zamboni, A.; Fabbri, S.; Di Thommazo, A. Using GQM and TAM to evaluate StArt–A tool that supports Systematic Review. CLEI Electron. J. 2012, 15, 1–13. Available online: https://clei.org/cleiej/index.php/cleiej/article/view/156/228 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, P.; Ferreira, M.J. The use of response systems in the learning-teaching process. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Barcelona, Spain, 18–21 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6877017 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiliche, R.; Rentería-Ramos, R.; De Brito Junior, I.; Luna, A.; Chong, M. Using Spatial Patterns of COVID-19 to Build a Framework for Economic Reactivation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito Junior, I.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y.; Saraiva, F.A.; Bruno, N.D.C.; Da Silva, R.F.; Hino, C.M.; Aguiar, L.L.; de Ataide, I.M.F. Panic Buying Behavior Analysis according to Consumer Income and Product Type during COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, B.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Smith Cornejo, N.R.; Rodríguez Calvo, E.Z. An IoMT platform for an integrated sustainable energy-efficient disaster relief supply chain to prevent severity-driven disruptions during pandemics. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 35, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, B.; Smith, N.R.; Gholian-Jouybari, F.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. An optimization framework for emergency supply chains prioritizing elderly populations during pandemics. Supply Chain Anal. 2025, 11, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kant, R.; Shankar, R. Modeling the enablers of humanitarian supply chain management: A hybrid group decision-making approach. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 166–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Shardeo, V.; Dwivedi, A.; Madaan, J.; Varma, N. Barriers to sustainability in humanitarian medical supply chains. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1794–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroof, A.; Khalid, Q.S.; Mahmood, M.; Naeem, K.; Maqsood, S.; Khattak, S.B.; Ayvaz, B. Vehicle Routing Optimization for Humanitarian Supply Chain: A Systematic Review of Approaches and Solutions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127157–127175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Seo, H. Selecting Disaster Waste Transportation Routes to Reduce Overlapping of Transportation Routes after Floods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombart, M.; Pierrat, K.; Redon, M. Port-au-Prince: Un « projectorat » haïtien ou l’urbanisme de projets humanitaires en question. Cah. Am. Lat. 2014, 2014, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, J.M.; Kumar, S. Impact of Incorporating Returns into Pre-Disaster Deployments for Rapid-Onset Predictable Disasters. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraud, H.; Barroca, B.; Hubert, G. Assessing the resilience of urban technical networks: From theory to application to waste management. In Resilience and Urban Risk Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 113–120. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203072820/chapters/10.1201/b12994-17 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Carnero Quispe, M.F.; Couto, A.S.; De Brito Junior, I.; Cunha, L.R.A.; Siqueira, R.M.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y. Humanitarian Logistics Prioritization Models: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2024, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrydziushka, D.; Pasha, U.; Hoff, A. An Extended Model for Disaster Relief Operations Used on the Hagibis Typhoon Case in Japan. Logistics 2021, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontoc, G.D.; Diola, M.B.L.D.; Peralta, M.H.T. Multi-criteria evaluation of suitable locations for temporary disaster waste storage sites: The case of Cavite, Philippines. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 2794–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Gazzoni, W.C.; Aguila, Z.J. The relationship between Humanitarian Logistics and Reverse Logistics: Characteristics, actions, and singularities between both. South Fla. J. Dev. 2021, 2, 3963–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraud, H.; Barroca, B.; Hubert, G. Functional analysis, a resilience improvement tool applied to a waste management system – application to the “household waste management chain”. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 3671–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasena, G. Sustainable Post-Disaster Waste Management: Construction and Demolition Debris. In Post-Disaster Reconstruction of the Built Environment, 1st ed.; Amaratunga, D., Haigh, R., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 251–267. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444344943.ch14 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- De Cair, S.D.; Cardarelli, J.J. Recovery, Resilience and Reality: Going Beyond NCRP Report No. 175. Health Phys. 2018, 114, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regattieri, A.; Piana, F.; Bortolini, M.; Gamberi, M.; Ferrari, E. Innovative portable solar cooker using the packaging waste of humanitarian supplies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, M.; Manuel Hernández-Castellano, P.; Alexis Alonso-Sánchez, J.; Gregorio Quevedo-Gutiérrez, E. The Challenge of the Gender Gap and the Lack of STEM Vocations in ESO and Baccalaureate. IEEE Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2024, 19, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.I.; Wilson, D.; Gomez-Kervin, E.; Rosson, L.; Long, J. EcoPrinting: Investigation of Solar Powered Plastic Recycling and Additive Manufacturing for Enhanced Waste Management and Sustainable Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Long Beach, CA, USA, 11–13 November 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8671370/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Till, J.E.; McBaugh, D. Practical and Scientifically Based Approaches for Cleanup and Site Restoration. Health Phys. 2005, 89, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whicker, J.J.; Janecky, D.R.; Doerr, T.B. Adaptive Management: A Paradigm for Remediation of Public Facilities Following a Terrorist Attack. Risk Anal. 2008, 28, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, M.; Vaccari, M. How to assess solid waste management in armed conflicts? A new methodology applied to the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2014, 32, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassa, R.; Bocanet, A. Developing a sustainable operation management system for food charity organizations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regattieri, A.; Gamberi, M.; Bortolini, M.; Piana, F. Innovative Solutions for Reusing Packaging Waste Materials in Humanitarian Logistics. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regattieri, A.; Santarelli, G.; Piana, F.; Gamberi, M. Classification of Technical Requirements and the Means of Addressing the Problem of Waste Management in a Refugee Camp. In Humanitarian Logistics and Sustainability; Klumpp, M., De Leeuw, S., Regattieri, A., De Souza, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Logistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 169–192. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-15455-8_10 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Yang, X.S.; Zheng, X.X.; Zhang, T.Y.; Du, Y.; Long, F. Waste Electrical and Electronic Fund Policy: Current Status and Evaluation of Implementation in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beraud, H.; Barroca, B.; Serre, D.; Hubert, G. Making Urban Territories More Resilient to Flooding by Improving the Resilience of Their Waste Management Network: A Methodology for Analysing Dysfunctions in Waste Management Networks during and after Flooding. In Vulnerability, Uncertainty, and Risk; American Society of Civil Engineers: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2011; pp. 425–432. Available online: http://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/41170%28400%2952 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Zhuravleva, A. Reverse supply chains of non-profit organizations for textile reuse. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 14, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Espíndola, O.; Ahmadi, H.; Gastélum-Chavira, D.; Ahumada-Valenzuela, O.; Chowdhury, S.; Dey, P.K.; Albores, P. Humanitarian logistics optimization models: An investigation of decision-maker involvement and directions to promote implementation. Socioecon. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Dutta, P. Thematic review of healthcare supply chain in disasters with challenges and future research directions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 100, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadi, D.S.; Basheer Abdullah, D. Domains and Impact of AI in IoT for Environmental Monitoring and Management: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (CSASE), Duhok, Iraq, 15–17 April 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 258–265. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/11054006/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Lahjouji, M.; Bassou, A.A.; Alami, J.E.; Hlyal, M.; Lahjouji, O. A New Mathematic Model for Humanitarian Pharmaceutical Supply Chain to Reduce Obsolesence Cost. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 3107–3119. [Google Scholar]

- De La Torre, N.; Espinosa, M.M.; Domínguez, M. Rapid Prototyping in Humanitarian Aid to Manufacture Last Mile Vehicles Spare Parts: An Implementation Plan. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kant, R.; Shankar, R. Evaluating solutions to overcome humanitarian supply chain management barriers: A hybrid fuzzy SWARA–Fuzzy WASPAS approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusin, S.; Ebaidalla, E.M.; Al-Thani, M.F. Contribution of Non-profit Organizations to Food Security and Sustainability in the State of Qatar. In Sustainable Qatar; Cochrane, L., Al-Hababi, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 211–228. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-7398-7_12 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Shahrasbi, A.; Shokouhyar, S.; Zeidyahyaee, N. Consumers’ behavior towards electronic wastes from a sustainable development point of view: An exploration of differences between developed and developing countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1736–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, P.; Qing, X. Building Resilience Through Disaster Waste Management—UN Environment’s Experiences and Approaches. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2018, 50, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha-da-Gama, F. Facility Location in Logistics and Transportation: An enduring relationship. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 166, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korucuk, S.; Aytekin, A.; Görçün, Ö.; Simic, V.; Faruk Görçün, Ö. Warehouse site selection for humanitarian relief organizations using an interval-valued fermatean fuzzy LOPCOW-RAFSI model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 192, 110160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, J.; Marcinkowski, J. Initiators and motives for cooperation in humanitarian supply chains. Logforum 2022, 18, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajani, M.; Torabi, S.A. A mixed procurement model for humanitarian relief chains. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 10, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Islam, M.A.; Kumar, M.; Hossain, M.; Bhattacharya, P.; Islam, M.T.; Hossen, F.; Hossain, S.; Islam, M.S.; Uddin, M.; et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in the vicinity of COVID-19 isolation Centre in Bangladesh: Variation along the sewer network. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friday, D.; Savage, D.A.; Melnyk, S.A.; Harrison, N.; Ryan, S.; Wechtler, H. A collaborative approach to maintaining optimal inventory and mitigating stockout risks during a pandemic: Capabilities for enabling health-care supply chain resilience. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 11, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Lauras, M.; Van Wassenhove, L. A model to define and assess the agility of supply chains: Building on humanitarian experience. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinyazan, F.G.; Rancourt, M.; Verter, V. Improving Transportation Procurement in the Humanitarian Sector: A Data-driven Approach for Abnormally Low Bid Detection. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 1082–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disaster Type | Percentage of Studies (%) | Focal Areas of Reverse Logistics and Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Pandemics and public-health emergencies | 17 | Management of medical waste (hazardous and recyclable), return/donation of pharmaceuticals, redistribution of surplus supplies (food and essential items), and equity in access to resources, with emphasis on reducing environmental impacts and prioritising vulnerable groups. |