Artificial Intelligence-Driven Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: Pathways to Competitive Advantage in the Hotel Industry

Abstract

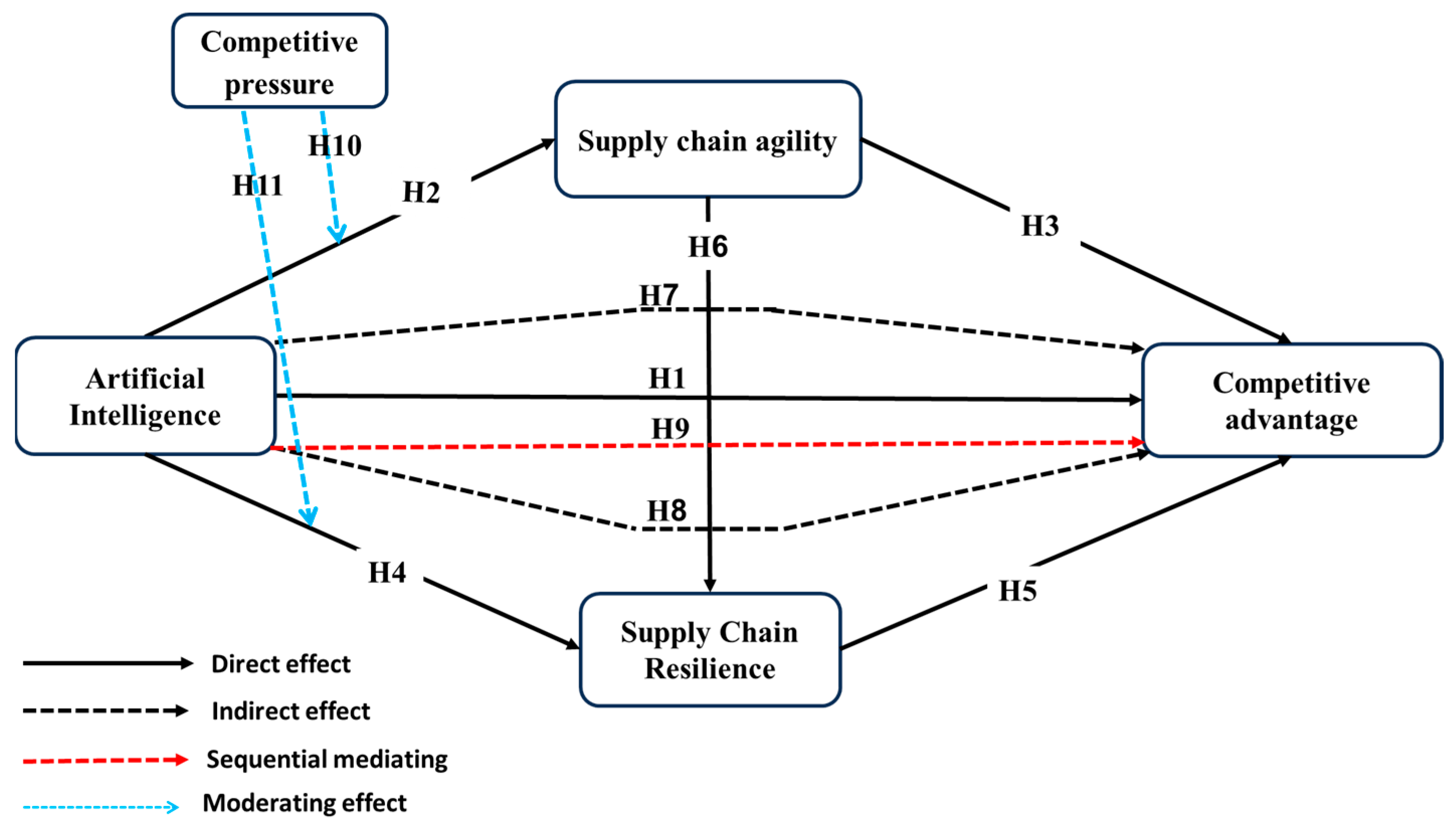

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Competitive Advantage (CA)

2.2. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Supply Chain Agility (SCA)

2.3. Supply Chain Agility (SCA) and Competitive Advantage (CA)

2.4. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Supply Chain Resilience (SCR)

2.5. Supply Chain Resilience (SCR) and Competitive Advantage (CA)

2.6. Supply Chain Agility (SCA) and Supply Chain Resilience (SCR)

2.7. Supply Chain Agility as Mediator

2.8. Supply Chain Resilience as a Mediator

2.9. SCA and SCR Sequentially Mediate the Link from AI and CA

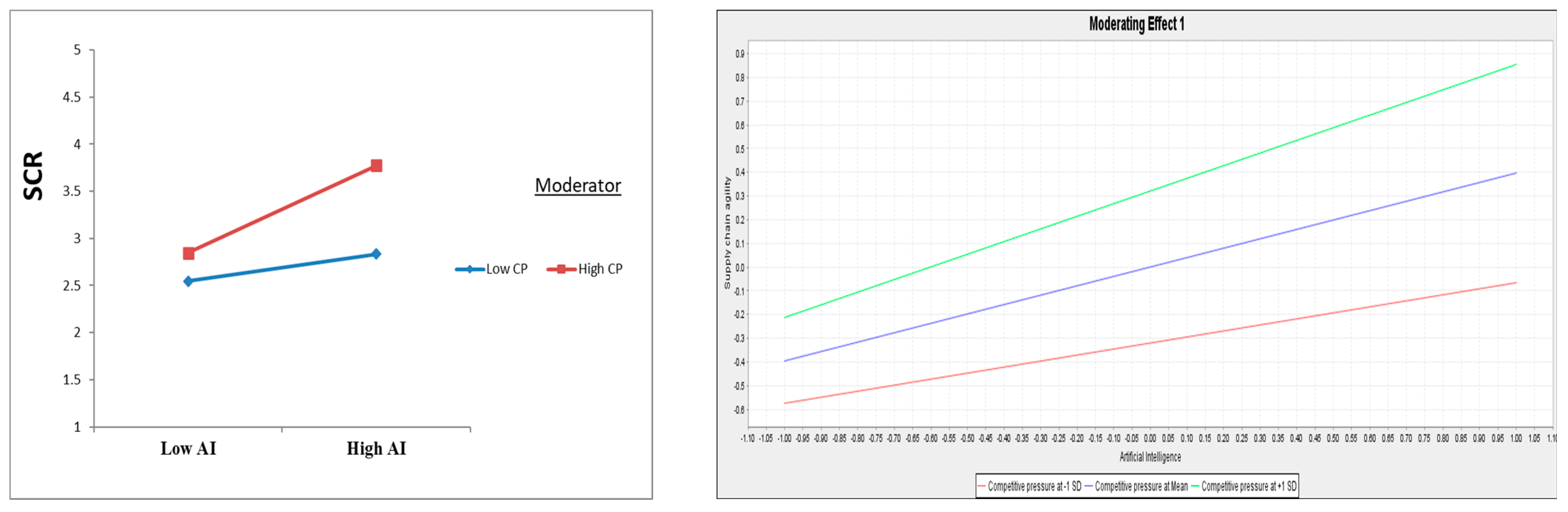

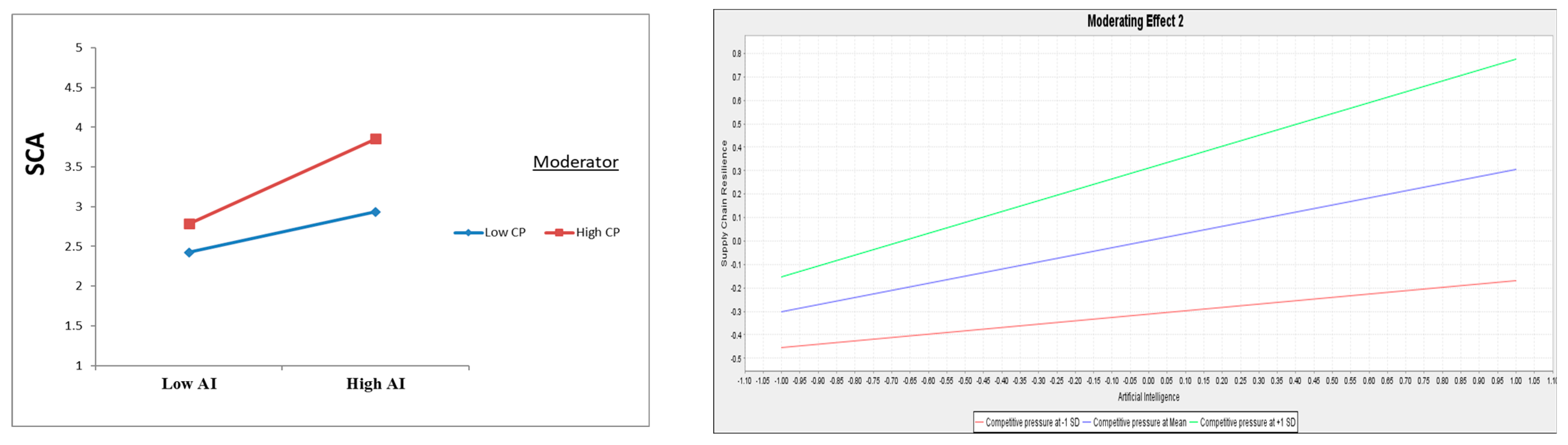

2.10. Competitive Pressure (CP) as a Moderator

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

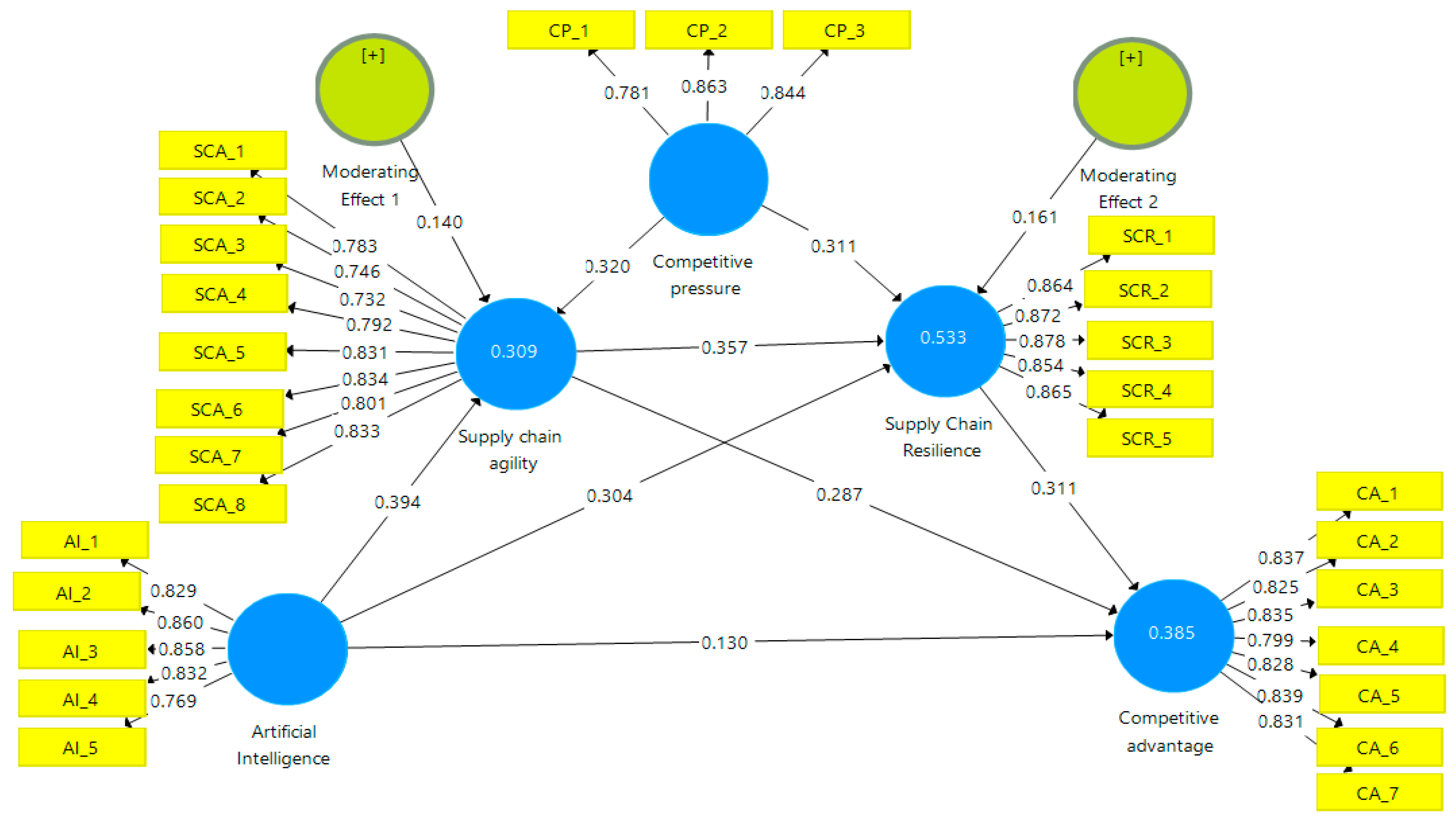

4.3. Structural Model and Testing Hypotheses

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Study Variables Measures

| Artificial intelligence |

| − We possess the infrastructure and skilled resources to apply AI information processing system |

| − We use AI techniques to forecast and predict environmental behavior |

| − We develop statistical, self-learning, and prediction using AI techniques |

| − We use AI techniques at all level of the supply chain |

| − We use AI outcomes in a shared way to inform supply chain decision-making |

| Competitive advantage |

| − Compared with our competitors, we offer unique benefits and novel features to our customers |

| − Compared with our competitors, we offer high quality products to our customers |

| − Compared with our competitors, we provide dependable delivery |

| − Compared with our competitors, we provide customized products |

| − Compared with our competitors, we deliver products to the market quickly |

| − Compared with our competitors, we offer competitive prices |

| − Compared with our competitors, we are able to compete based on quality |

| Supply chain agility |

| − Speed in reducing service lead time |

| − Speed in reducing product development cycle time |

| − Speed in increasing frequency of new product introductions |

| − Speed in increasing levels of product customization |

| − Speed in adjusting delivery capability |

| − Speed in improving customer service |

| − Speed in improving delivery reliability |

| − Speed in improving responsiveness to changing market needs |

| Supply Chain Resilience |

| − Our hotel’s supply chain is well prepared to face constraints of supply chain disruptions |

| − Our hotel’s supply chain can rapidly plan and execute contingency plans during disruptions |

| − Our hotel’s supply chain can adequately respond to unexpected disruptions by quickly restoring its product flow |

| − Our hotel’s supply chain can swiftly return to its original state after being disrupted |

| − Our hotel’s supply chain can gain a superior state compared to its original state after being disrupted |

| Competitive pressure |

| − Our hotel seeks AI-driven solutions from its suppliers because our competitors are also demanding similar AI solutions from their suppliers |

| − Our industry is progressively shifting toward adopting AI-oriented production and business processes |

| − Our hotel is receiving support from government institutions for adopting AI-based products and solutions |

References

- Pillai, S.G.; Haldorai, K.; Seo, W.S.; Kim, W.G. COVID-19 and Hospitality 5.0: Redefining Hospitality Operations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Kamar, M.; Albadry, O.M.; Sheikhelsouk, S.; Ali Al-Abyadh, M.H.; Alsetoohy, O. Dynamic Capabilities Influence on the Operational Performance of Hotel Food Supply Chains: A Mediation-Moderation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Technology and competitive advantage. J. Bus. Strategy 1985, 5, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Chou, S.-F.; Yu, T.-Y.; Hu, D.-C. Role of Big Data Capabilities in Enhancing Competitive Advantage and Performance in the Hospitality Sector: Knowledge-Based Dynamic Capabilities View. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K.; Hussain, M.; Gamage, T.C.; Papastathopoulos, A. Effects of Resource Orchestration, Strategic Information Exchange Capabilities, and Digital Orientation on Innovation and Performance of Hotel Supply Chains. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 117, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloet, M.; Samson, D. Knowledge and Innovation Management to Support Supply Chain Innovation and Sustainability Practices. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2022, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hou, J. Applying the Theory of Constraints Principles to Tourism Supply Chain Management. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Nur, M. Integration of Supply Chain Management and Tourism: An Empirical Study from the Hotel Industry of Indonesia. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchmann, T.; Topp, M.; Seeler, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain. Forum Int. J. 2022, 23, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, T.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.-L.; Pelechano-Barahona, E. Managing Relationships in the Tourism Supply Chain to Overcome Epidemic Outbreaks: The Case of COVID-19 and the Hospitality Industry in Spain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, A.; Agrawal, R. Is Artificial Intelligence an Enabler of Supply Chain Resiliency Post COVID-19? An Exploratory State-of-the-Art Review for Future Research. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourism Resilience in the ‘New Normal’: Beyond Jingle and Jangle Fallacies? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, D. Necessary Condition Analysis of Organisational Capabilities for a Resilient Service Operation in the Hotel Industry in Ghana. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Christofi, M.; Tarba, S. Contextualizing Small Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Small Business Owner-Managers. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 1351–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Quaddus, M. Supply Chain Resilience: Conceptualization and Scale Development Using Dynamic Capability Theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 188, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizullah, A.; Rehman, Z.U.; Ali, I.; Murad, W.; Muhammad, N.; Ullah, W.; Häder, D.P. Chlorophyll derivatives can be an efficient weapon in the fight against dengue. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 4321–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, M.; Demir, Ş.Ş. The Relationship between Technology Investments, Innovation Strategies, and Competitive Performance in the Hospitality Industry: A Mixed Methods Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 128, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Rana, N.P.; Tamilmani, K.; Sharma, A. The Effect of AI-Based CRM on Organization Performance and Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Analysis in the B2B Context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 97, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Gupta, M. Artificial Intelligence Capability: Conceptualization, Measurement Calibration, and Empirical Study on Its Impact on Organizational Creativity and Firm Performance. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, B.; Wu, L. AI on Drugs: Can Artificial Intelligence Accelerate Drug Development? Evidence from a Large-Scale Examination of Bio-Pharma Firms. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 1451–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Mani, V.; Kamble, S.S.; Khan, S.A.R.; Verma, S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Innovation for Enhancing Supply Chain Resilience and Performance under the Effect of Supply Chain Dynamism: An Empirical Investigation. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 333, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, K.; Chu, F. The Two Faces of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Analyzing How AI Usage Shapes Employee Behaviors in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Yang, Y.; Qin, D.; Cao, X.; Xu, H. Artificial Intelligence Service Recovery: The Role of Empathic Response in Hospitality Customers’ Continuous Usage Intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.C.; Tan, P.J.B. Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things to Improve Smart Hospitality Services. Internet Things 2025, 31, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahidi, F.; Kaluvilla, B.B.; Mulla, T. Embracing the New Era: Artificial Intelligence and Its Multifaceted Impact on the Hospitality Industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daios, A.; Kladovasilakis, N.; Kelemis, A.; Kostavelis, I. AI Applications in Supply Chain Management: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, N.T.M.; Pham, T.H.; Siriwardana, A.; Nguyen, L.C.; Tran, D.L.A. A Bibliometric Review of Digitalization in Tourism Supply Chains in the Context of Industry 4.0. Strateg. Chang. 2025, 34, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A. Adoption of Robust Business Analytics for Product Innovation and Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Data-Driven Culture. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 339, 1757–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balezentis, T.; Zickiene, A.; Volkov, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Morkunas, M.; Dabkiene, V.; Ribasauskiene, E. Measures for the Viable Agri-Food Supply Chains: A Multi-Criteria Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhil, N.S.B.; Raj, R.; Kumar, V.; Gangaraju, P.K.; De, T. An Agility and Performance Assessment Framework for Supply Chains Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling. Supply Chain Anal. 2025, 9, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism Supply Chain Management: A New Research Agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, V.H.I.; Hong, J.F.L.; Wong, I.A. The Evolution of Triadic Relationships in a Tourism Supply Chain through Coopetition. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Roy, S.; Raju, G.A. Tourism Supply Chain Agility: An Empirical Examination Using Resource-Based View. Int. J. Bus. Forecast. Mark. Intell. 2016, 2, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Dubey, R.K. Role of Tourism IT Adoption and Risk Management Orientation on Tourism Agility and Resilience: Impact on Sustainable Tourism Supply Chain Performance. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.C.S. Technological Capabilities That Enhance Tourism Supply Chain Agility: Role of E-Marketplace Systems. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-T.; Yang, L.-X.; Chen, M.-L. Impact of Temperature Variability on Supply Chain Resilience in China: Mechanisms and Insights. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107866. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, H.; ur Rehman, A.; Iftikhar, A.; ul Haq, M.Z.; Akbar, U.; Kamal, M.M. Digital Transformation: Unlocking Supply Chain Resilience through Adaptability and Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2025, 219, 124234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, T.; Hesaraki, A.F.; Morsch, J.P.M. Exploring IT-Driven Supply Chain Capabilities and Resilience: The Roles of Supply Chain Risk Management and Complexity. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2025, 30, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, R. Does the Integration of Digital and Real Economies Enhance Corporate Supply Chain Resilience? Evidence from China’s Listed Firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyuga, G.; Tanova, C. Assessing the Mediating Role of Knowledge Management in the Relationship between Technological Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Luo, X.; Xi, M. The Impact of Regional Artificial Intelligence Development on the Resilience of Enterprise Supply Chains. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P. Transforming Supply Chains Through AI: Demand Forecasting, Inventory Management, and Dynamic Optimization. Integr. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 1. Available online: https://ijstpublication.com/index.php/ijst/article/view/15 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Grover, N. AI-Enabled Supply Chain Optimization. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2025, 5, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C. The Smart City Pilot Policy and Corporate Supply Chain Resilience. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-Y.; Chang, K.-Y.; Wu, H.-M. Knowledge-Based Resilience and Robustness of Travel Agencies in Facing Tourism Supply Chain Disruptions. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, T.; Xi, X.; Li, W.H.; Liu, W. Geographic Proximity and Supply Chain Resilience: Unravelling Their Complex Dynamics in the Digital Age. Technovation 2025, 148, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Jiang, Y.; Chowdhury, M.; Hossain, M.I.; Akter, N. Building Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Resilience in Tourism Firms During COVID-19: A Staged Approach. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 713–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Shahzad, A.; Hassan, R. Organizational and Environmental Factors with the Mediating Role of E-Commerce and SME Performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, S.; Asgharian, H.; Liu, L.; Rei, M.; Zollo, M. Does Competitive Pressure Drive Effective Corporate Environmental Actions? J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 511, 145585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, M.; Jones, P. IT Strategy in the Hotel Industry in the Digital Era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Kumar, S. Linking Stakeholder and Competitive Pressure to Industry 4.0 and Performance: Mediating Effect of Environmental Commitment and Green Process Innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegan Joseph Jerome, J.; Sonwaney, V.; Bryde, D.; Graham, G. Achieving Competitive Advantage through Technology-Driven Proactive Supply Chain Risk Management: An Empirical Study. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 332, 149–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabi, S.M.; Al-Ababneh, M.M.; Al Qsssem, A.H.; Afaneh, J.A.A.; Elshaer, I.A. Green Human Resource Management Practices and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and pro-Environmental Behavior. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2328316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzaouia, I.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Information Technology in the Hotel Industry. An Analysis in a Developing Country. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, B. Supply Chain Decarbonisation Effects of Artificial Intelligence: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 101, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin Chang, H.; Hong Wong, K.; Sheng Chiu, W. The Effects of Business Systems Leveraging on Supply Chain Performance: Process Innovation and Uncertainty as Moderators. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Bryde, D.J.; Giannakis, M.; Foropon, C.; Roubaud, D.; Hazen, B.T. Big Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence Pathway to Operational Performance under the Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Environmental Dynamism: A Study of Manufacturing Organisations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 226, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The Comparative Advantage Theory of Competition. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J. Developing a Model for Supply Chain Agility and Innovativeness to Enhance Firms’ Competitive Advantage. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jacobs, M.A.; Chavez, R.; Yang, J. Dynamism, Disruption Orientation, and Resilience in the Supply Chain and the Impacts on Financial Performance: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 218, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, N.; Gunasekaran, A.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Agility and Resilience as Antecedents of Supply Chain Performance under Moderating Effects of Organizational Culture within the Humanitarian Setting: A Dynamic Capability View. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M. Determinants of Green Procurement Implementation and Its Impact on Firm Performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.; Ahmad, M.S.; Abdulaziz, T.A.; Khairy, H.A.; Fayyad, S.; Lee, C. Catalyzing Green Change: The Impact of Tech-savvy Leaders on Innovative Behaviors. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5543–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The Robustness of Test Statistics to Nonnormality and Specification Error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Does My Structural Model Represent the Real Phenomenon: A Review of the Appropriate Use of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) Model Fit Indices. Mark. Rev. 2009, 9, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, F.; Rademaker, M.E.; Henseler, J. Assessing the Overall Fit of Composite Models Estimated by Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 1678–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling: Analyzing Latent and Emergent Variables; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fassott, G.; Henseler, J.; Coelho, P.S. Testing Moderating Effects in PLS Path Models with Composite Variables. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1887–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Li, M.; Qiu, H.; Bai, B.; Zhou, L. When the Servicescape Becomes Intelligent: Conceptualization, Assessment, and Implications for Hospitableness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, E.; Datta, A.; Prentice, C.; Leung, R. Artificial Intelligence through the Lens of Hospitality Employees: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 124, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsetoohy, O.; Ayoun, B.; Arous, S.; Megahed, F.; Nabil, G. Intelligent Agent Technology: What Affects Its Adoption in Hotel Food Supply Chain Management? J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangina, E.; Vlachos, I.P. The Changing Role of Information Technology in Food and Beverage Logistics Management: Beverage Network Optimisation Using Intelligent Agent Technology. J. Food Eng. 2005, 70, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Al-Aomar, R.; Melhem, H. Assessment of Lean-Green Practices on the Sustainable Performance of Hotel Supply Chains. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2448–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alqasa, K.M.A.; Afaneh, J.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Resilience for Sustainability: The Synergistic Role of Green Human Resources Management, Circular Economy, and Green Organizational Culture in the Hotel Industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bonn, M.A.; Ye, B.H. Hotel Employee’s Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Awareness and Its Impact on Turnover Intention: The Moderating Roles of Perceived Organizational Support and Competitive Psychological Climate. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Ashton, M.; Derqui, B.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G. Exploring How Artificial Intelligence (AI) Can Enable Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 9123–9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Saravanan, D. Exploring the Influence of Strategic Orientations on Tourism Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: An Empirical Investigation. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 612–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, A. Examining the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain Management from Industry 4.0 to 6.0: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, 1477044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.C.; Ribau, C.P.; Rodrigues, C.D.S.F. Green Supply Chain Practices in the Plastics Industry in Portugal. The Moderating Effects of Traceability, Ecocentricity, Environmental Culture, Environmental Uncertainty, Competitive Pressure, and Social Responsibility. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 5, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, X. Digital Transformation along the Supply Chain: Spillover Effects from Vertical Partnerships. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183, 114842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Rodríguez, T.F.; Taha, M.G. Supplier Innovativeness in Supply Chain Integration and Sustainable Performance in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Fisher, M. Supply Chain Inventory Management and the Value of Shared Information. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.J.; Paulraj, A. Understanding Supply Chain Management: Critical Research and a Theoretical Framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2004, 42, 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Younis, N.S. Born Not Made: The Impact of Six Entrepreneurial Personality Dimensions on Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence from Healthcare Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | λ | VIF | Mean | SD | SK | KU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AI: (α = 0.887, CR = 0.917, AVE = 0.689) | ||||||

| AI_1 | 0.829 | 2.296 | 3.657 | 1.317 | −0.605 | −0.791 |

| AI_2 | 0.860 | 2.721 | 3.775 | 1.250 | −0.665 | −0.612 |

| AI_3 | 0.858 | 2.573 | 3.762 | 1.316 | −0.738 | −0.662 |

| AI_4 | 0.832 | 2.092 | 3.630 | 1.418 | −0.625 | −0.929 |

| AI_5 | 0.769 | 1.856 | 3.451 | 1.327 | −0.427 | −0.925 |

| 2. CA: (α = 0.923, CR = 0.938, AVE = 0.685) | ||||||

| CA_1 | 0.837 | 2.615 | 3.428 | 1.417 | −0.281 | −1.257 |

| CA_2 | 0.825 | 2.958 | 3.573 | 1.385 | −0.380 | −1.233 |

| CA_3 | 0.835 | 2.859 | 3.692 | 1.307 | −0.506 | −0.932 |

| CA_4 | 0.799 | 2.403 | 3.512 | 1.369 | −0.428 | −0.998 |

| CA_5 | 0.828 | 2.643 | 3.625 | 1.343 | −0.511 | −0.945 |

| CA_6 | 0.839 | 2.612 | 3.634 | 1.302 | −0.554 | −0.755 |

| CA_7 | 0.831 | 2.419 | 3.833 | 1.394 | −0.783 | −0.806 |

| 3. SCA: (α = 0.916, CR = 0.932, AVE = 0.632) | ||||||

| SCA_1 | 0.783 | 2.201 | 3.199 | 1.261 | −0.149 | −0.892 |

| SCA_2 | 0.746 | 2.187 | 3.019 | 1.285 | 0.110 | −0.924 |

| SCA_3 | 0.732 | 2.134 | 2.840 | 1.312 | 0.254 | −0.931 |

| SCA_4 | 0.792 | 2.341 | 3.053 | 1.354 | 0.072 | −1.075 |

| SCA_5 | 0.831 | 2.715 | 3.148 | 1.358 | −0.097 | −1.140 |

| SCA_6 | 0.834 | 2.946 | 3.070 | 1.380 | 0.046 | −1.178 |

| SCA_7 | 0.801 | 2.550 | 2.910 | 1.451 | 0.135 | −1.285 |

| SCA_8 | 0.833 | 2.649 | 3.130 | 1.487 | −0.071 | −1.367 |

| 4. SCR: (α = 0.917, CR = 0.938, AVE = 0.751) | ||||||

| SCR_1 | 0.864 | 2.544 | 3.576 | 1.428 | −0.546 | −1.066 |

| SCR_2 | 0.872 | 2.748 | 3.720 | 1.292 | −0.655 | −0.640 |

| SCR_3 | 0.878 | 2.909 | 3.685 | 1.318 | −0.644 | −0.712 |

| SCR_4 | 0.854 | 2.611 | 3.655 | 1.350 | −0.633 | −0.789 |

| SCR_5 | 0.865 | 2.650 | 3.688 | 1.334 | −0.628 | −0.746 |

| 5. CP: (α = 0.775, CR = 0.869, AVE = 0.689) | ||||||

| CP_1 | 0.781 | 1.518 | 3.602 | 1.294 | −0.520 | −0.728 |

| CP_2 | 0.863 | 1.704 | 3.685 | 1.237 | −0.486 | −0.738 |

| CP_3 | 0.844 | 1.604 | 3.748 | 1.252 | −0.626 | −0.623 |

| AI | CA | CP | SCR | SCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | 0.830 | ||||

| CA | 0.435 | 0.828 | |||

| CP | 0.459 | 0.436 | 0.830 | ||

| SCR | 0.542 | 0.558 | 0.532 | 0.867 | |

| SCA | 0.476 | 0.540 | 0.436 | 0.616 | 0.795 |

| AI | CA | CP | SCR | SCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||||

| CA | 0.475 | ||||

| CP | 0.535 | 0.505 | |||

| SCR | 0.592 | 0.601 | 0.625 | ||

| SCA | 0.521 | 0.583 | 0.507 | 0.668 |

| Hypothesis | β | t | p | F2 | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| H1: AI → CA | 0.130 | 2.149 | 0.032 | 0.019 | ✔ | |

| H2: AI → SCA | 0.394 | 7.760 | 0.000 | 0.166 | ✔ | |

| H3: SCA → CA | 0.287 | 5.049 | 0.000 | 0.079 | ✔ | |

| H4: AI → SCR | 0.304 | 6.482 | 0.000 | 0.125 | ✔ | |

| H5: SCR → CA | 0.311 | 4.975 | 0.000 | 0.085 | ✔ | |

| H6: SCA → SCR | 0.357 | 10.205 | 0.000 | 0.188 | ✔ | |

| Single mediating effect | CI | |||||

| H7: AI → SCA → CA | 0.113 | 3.948 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.175 | ✔ |

| H8: AI → SCR → CA | 0.094 | 3.902 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.146 | ✔ |

| Sequential mediating effect | ||||||

| H10: AI → SCA → SCR → AI | 0.044 | 3.779 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.069 | ✔ |

| Moderating effect | ||||||

| H11a: AI × CP → SCA | 0.140 | 3.080 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 0.225 | ✔ |

| H11b: AI × CP → SCR | 0.161 | 4.370 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.227 | ✔ |

| Competitive advantage | R2 | 0.385 | Q2 | 0.244 | ||

| Supply Chain Resilience | R2 | 0.533 | Q2 | 0.368 | ||

| Supply chain agility | R2 | 0.309 | Q2 | 0.179 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Aljoghaiman, A.; Mansor, M.; Salama, M.A.; Fayyad, S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: Pathways to Competitive Advantage in the Hotel Industry. Logistics 2026, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010005

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Aljoghaiman A, Mansor M, Salama MA, Fayyad S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: Pathways to Competitive Advantage in the Hotel Industry. Logistics. 2026; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Abdulaziz Aljoghaiman, Mahmoud Mansor, Mahmoud Ahmed Salama, and Sameh Fayyad. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence-Driven Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: Pathways to Competitive Advantage in the Hotel Industry" Logistics 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010005

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Aljoghaiman, A., Mansor, M., Salama, M. A., & Fayyad, S. (2026). Artificial Intelligence-Driven Supply Chain Agility and Resilience: Pathways to Competitive Advantage in the Hotel Industry. Logistics, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010005