1. Introduction

The frequency and intensity of natural disasters have increased in recent decades, causing significant human, social, and economic impacts [

1]. Events such as floods, droughts, earthquakes, and hurricanes disrupt entire communities, can displace populations, damage essential infrastructure at different levels, and require a rapid mobilization of resources to reduce harm and save lives [

2].

Between 2000 and 2022, more than 3 billion people were affected, with losses exceeding hundreds of billions of dollars. Floods and storms remain the most recurrent events with the highest number of victims, reinforcing the need for more agile and coordinated response systems. The increasing pressure on emergency teams highlights that operational decisions need to be made in a structured, transparent manner and within increasingly shorter time windows [

3,

4].

According to [

5], a disaster can be defined as a sudden event that exceeds a society’s response capacity, causing large-scale human, material, economic, or environmental losses. Although many disasters have natural origins, human factors such as unplanned land use, environmental degradation, and poor planning increase their severity and frequency. The interaction between hazard, vulnerability, and low mitigation capacity forms the conceptual basis that explains why certain events become disasters [

6].

Disaster management aims to reduce these consequences. It is traditionally structured in a cycle composed of four phases: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. The first two phases are proactive. They seek to reduce long-term risks, strengthen resilience, and improve response capacity through preventive policies, planning, training, and early warning systems. The response and recovery phases are reactive. The response phase includes emergency actions to protect lives, provide assistance, and coordinate the use of limited resources. The recovery phase focuses on restoring infrastructure and normalizing social and economic activities [

7]. The cycle is continuous, and the lessons learned in one phase feed into the others, promoting continuous improvement of management policies and strategies [

6].

Among the four phases, the response phase demands the highest level of agility, accuracy, and coordination among multiple actors. When a disaster occurs, the time available for action is limited, and decisions must be made based on incomplete information and rapidly changing conditions [

8]. At this stage, humanitarian logistics plays a central role in organizing supply flows, mobilizing rescue teams, and, above all, ensuring the efficient allocation of available resources [

9].

Among these resources, rescue helicopters stand out for their ability to reach isolated areas, transport victims, and deliver medical supplies to places where other means cannot operate [

10]. However, deciding where and when to deploy these aircraft is a highly complex process that involves multiple criteria, such as weather conditions, flight time, crew availability, risk level, and estimated number of victims, all under strong time pressure and with potentially irreversible consequences [

11].

Over the past decades, different quantitative approaches have been applied to support decision-making in humanitarian operations. Optimization models (linear, integer, or multi-objective), stochastic or agent-based simulations, heuristics, and expert systems based on fuzzy logic are widely used to maximize logistical efficiency and minimize costs or response times [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Despite their usefulness, these models often assume ideal information conditions and experienced operators, which rarely reflect the reality of field operations. In real disaster situations, the available data are uncertain, incomplete, or constantly changing; decision time is short; and qualitative factors such as team experience, terrain accessibility, or social impact make these models, in most cases, difficult to implement.

One way to improve the allocation of available resources during relief operations is through an Integrated Command and Control Center, or Management Center (MC) [

20]. The MC is operated by trained staff, and one of them, the resource allocator, is responsible for assigning rescue units to reach the victims. He is the main decision-maker in this process.

The resource allocator needs solid knowledge and continuous training to deal with many types of situations and different levels of severity, such as floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, tsunamis, hurricanes, droughts, and volcanic eruptions. Even with good skills and training, experience remains essential for making sound decisions. However, due to operational or economic limitations, the allocator is not always the most experienced operator available. This condition can make it difficult to identify the best, or even a reasonably good, option when allocating rescue units.

In this context, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) emerges as a promising alternative to support complex decisions under uncertainty. MCDA allows the integration of quantitative and qualitative criteria, the incorporation of value judgments, and the structuring of decision-makers’ preferences in a transparent and traceable way.

The literature presents relevant advances in the application of multi-criteria methods in humanitarian logistics, but some gaps remain largely unexplored. One of them is how efficiency and operational safety criteria can be considered together in air rescue decisions. Another gap is the limited use of value-driven approaches, which could make the decision-maker’s fundamental objectives and the related trade-offs more explicit. The third gap relates to the need for tools applicable to operators with different levels of experience, offering structured support in environments characterized by uncertainty and strong time pressure. These gaps justify the development of an approach that combines objective structuring and multi-criteria evaluation in a framework consistent with the practical demands of the response phase.

The present study proposes a decision-support methodology based on MCDA, integrating VFT and MAVT, to assist the allocation of air rescue units during the disaster response phase. The approach provides a structured and transparent process that allows the decision-maker to compare alternatives, visualize trade-offs between efficiency and safety, and adopt more consistent solutions even under time pressure and uncertainty. By bringing theoretical models closer to operational practice, this work contributes to the consolidation of decision-support tools applicable to real emergency scenarios.

The main contributions of this study are:

to structure the fundamental objectives of air rescue unit allocation through VFT, making explicit the trade-offs between safety and efficiency;

to apply MAVT to compare simulated alternatives under measurable and operationally relevant criteria;

to offer a transparent and traceable decision-making process, useful for operators with different levels of experience;

to assess the sensitivity of decisions to changes in preferences, allowing a clearer understanding of how different weights influence the ranking of alternatives.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the literature review;

Section 3 describes the decision context and data considered;

Section 4 details the application of the proposed method;

Section 5 presents the discussion; and

Section 6 the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Decision-Making Under Uncertainty in Disasters and Emergencies

Disaster management decisions are made under significant uncertainty, time pressure, and resource scarcity. Available information is often incomplete, inaccurate, or contradictory, and the impacts of alternatives can rarely be estimated before the decision has to be made. This context reinforces the need for structured decision-support methods capable of representing multiple objectives and explicitly addressing uncertainty.

Reference [

21] analyzes disaster decision-making through intelligent decision-support models, emphasizing the interaction between uncertainty, scarce information, and humanitarian logistics. The authors propose two models: one for assessing consequences in the initial phases after a disaster and another for the “last mile” distribution of humanitarian aid, both based on MCDA. These models illustrate how MCDA can structure decisions in contexts involving multiple actors, conflicting objectives, and incomplete data.

Reference [

22] shows how scenario planning can be combined with MCDA to support strategic decisions under uncertainty. Scenario planning helps create different possible situations that decision-makers may face, while MCDA allows a structured comparison of how each alternative performs in these situations, including through regret-based measures. This combined approach is particularly relevant in disaster management, where alternatives may perform very differently depending on how the situation evolves.

Recent work also emphasizes the role of information systems in uncertain environments. Reference [

23] identifies critical success factors for Emergency Information Response Systems (EIRS) using a Similar-DEMATEL approach adapted to incomplete assessment information. Their findings highlight the importance of information flow capabilities, monitoring and early warning, and organizational participation, showing that uncertainty is not only a technical issue but also depends on the institutional and informational capacities that support decision-making.

From a more strategic perspective, Reference [

24] argues that emergency management should be framed as a strategic management problem. Integration with strategic management principles brings benefits such as long-term thinking, capacity building, and greater accountability.

Other contributions explore risk communication and public participation under uncertainty. Reference [

25] tests a structured and value-oriented approach to deliberative communication of environmental risks. The authors show that a structured, value-focused process leads lay participants to more thoughtful and better-informed decisions, allowing for discussion of a broader range of issues and value trade-offs. This result is particularly relevant in disasters involving multiple stakeholders, including communities and agencies, where the legitimacy of decisions is crucial.

In summary, this literature shows that decisions in disaster and emergency management occur under high uncertainty and involve multiple conflicting objectives. MCDA, scenario planning, and structured risk-communication approaches offer valuable frameworks to support such decisions. However, most applications focus on the strategic, planning, or information-systems levels, rather than on the operational problem of allocating response resources during the emergency phase.

2.2. Value-Focused Thinking and Value-Driven Decision Support

Several studies in different areas have adopted VFT or value-oriented approaches. Although some studies do not address emergencies directly, they illustrate how VFT can translate broad value concerns into operational criteria. This is useful for structuring disaster management problems guided by social and ethical value.

Reference [

26] applies VFT to environmental management in civil construction, developing a qualitative value model based on life-cycle assessment to compare roof structures. The study concludes that the VFT approach helps identify alternatives that better meet environmental requirements and can be extended to include economic and social dimensions.

Reference [

27] integrates VFT with managerial to study decisions in corporate sustainability. Based on a survey of senior procurement managers, the author shows that stronger sustainability values are associated with more holistic perceptions of the tensions between environmental, social, and economic objectives. This result links value structures, cognitive frameworks, and decision-making practices, which is also important in emergency contexts, where trade-offs between efficiency, equity, and safety are required.

Reference [

28] uses VFT as a framework for defining objectives in global conservation planning teams. The five-step process, from eliciting individual values to structuring multiple objectives and performing a quality check, shows that VFT can be applied to both experienced and newly formed teams.

VFT has been combined with other problem-structuring approaches and with MCDA techniques to build criteria hierarchies and represent stakeholder values in complex infrastructure decisions. In the energy sector, Reference [

29] combines Soft Systems Methodology and VFT to structure decision support in the energy performance evaluation of school buildings, using the process to build a criteria tree for subsequent MCDA models. Reference [

30] integrates VFT with PRO-METHEE for the selection of distributed generation project portfolios, capturing the decision-maker’s preferences regarding conflicting sustainability and investment criteria.

Despite the robust literature on VFT, applications explicitly focused on emergency or disaster management remain rare. Most studies concentrate on environmental management, sustainability, energy, or conservation. This gap opens an opportunity to use VFT to structure values and objectives in emergency contexts.

2.3. VIKOR and Commitment Ranking in Disaster and Emergency Contexts

The VIKOR method is an outranking MCDA approach designed to identify compromise solutions that balance group utility and individual regret. It is suitable for public and humanitarian decisions involving multiple stakeholders.

Recent studies connect the VIKOR method to several emergency and disaster contexts. Reference [

31] shows that VIKOR and fuzzy VIKOR have been applied across at least 15 areas, including sustainability, renewable energy, and some disaster-related problems. Reference [

32] used a Bayesian BWM–VIKOR–TOPSIS model to assess hospital preparedness, identifying personnel and equipment as the most critical criteria. Reference [

33] combined VIKOR with multi-objective integer programming to plan electrification in post-disaster relief camps, balancing cost and performance of generation technologies. Reference [

34] applied fuzzy VIKOR to dual evacuation planning under dam-failure risk, considering road hazard, evacuation difficulty, and pedestrian demand. Reference [

35] used VIKOR with entropy weighting to identify critical hospitals in post-disaster urban networks, while Reference [

36] integrated VIKOR and GIS to select emergency logistics centers, emphasizing population density. Reference [

37] proposed an interval-valued dual hesitant fuzzy VIKOR model to evaluate community emergency responses under ambiguous preferences. Reference [

38] extended VIKOR with hesitant triangular fuzzy sets and cumulative prospect theory to optimize responses to hydrogen spills and explosions. Reference [

39] combined VIKOR with GAIA visualization to assess risks in perishable supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.4. Humanitarian Logistics, Supply Chains and Decision Support

The literature on logistics and humanitarian supply chains highlights supply chain management as a critical success factor in humanitarian operations. Reference [

40] provides evidences that supply chain activities account, on average, for nearly three-quarters of the total costs of humanitarian response, showing substantial potential for savings through improved logistics and procurement. Reference [

41] uses system dynamics to analyze how different operational arrangements (centralized, hybrid, decentralized), product characteristics, and disaster types affect humanitarian supply chain performance, including response cost, delivery time, and local economic impacts. They also examine preparedness investments and shocks such as COVID-19, emphasizing the need for robust performance indicators and explicit trade-off analysis.

Reference [

42] reviews challenges, solutions, and frameworks for the design and management of humanitarian supply chains, identifying persistent gaps in coordination, the role of digital technologies, and the integration of resilience and agility. Reference [

43] focuses on risk management in humanitarian aid delivery, identifying risk categories and showing how contextual factors at the country, organization, and crisis levels shape risk profiles.

Despite these advances, the logistics of emergency response using aircraft or helicopters remains less explored with MCDA methods. Most existing studies focus on facility location, supplier selection, preparedness assessment, or supply chain configuration. Operational decisions regarding the prioritization and deployment of rescue units, especially during the critical response phase, are still commonly addressed using single-objective optimization or queuing-based approaches, often with simplified representations of stakeholder values and uncertainty.

2.5. Research Gaps and Study Contribution

The reviewed literature shows three main points. First, decisions in disaster and emergency management take place under high uncertainty, with many stakeholders and conflicting objectives. MCDA has been used in several areas, such as strategic planning, risk communication, hospital preparedness, evacuation studies, and the location of logistics centers. Many of these applications use fuzzy and other uncertainty-handling techniques to work with incomplete information. Second, VFT offers a clear way to identify and structure the decision-maker’s values, but its use in emergency management is still limited. Most studies appear in environmental management, sustainability, energy, or conservation. Third, VIKOR and its extensions work well to identify compromise solutions in disaster-related and humanitarian supply chain problems. However, they are usually applied to static evaluation and ranking tasks, not to the near real-time allocation of resources during the response phase.

In this context, an important gap remains. There is a need for models that help decision-makers express the values and objectives that guide emergency response. There is also a need for models that represent the multi-criteria nature of allocating scarce rescue resources across different areas under uncertainty, and models that offer compromise solutions that are easy to interpret and useful for managers in humanitarian operations.

This study aims to address this gap by proposing a VFT-MCDA model to support the allocation of helicopter rescue missions in the disaster response phase. The approach combines concepts from Value-Focused Thinking and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in a single framework. The model organizes the decision problem around fundamental objectives that reflect humanitarian values and the operational constraints of the mission. It also uses a compromise-solution perspective to support the allocation of rescue units under uncertainty. With this structure, the study connects theoretical advances in VFT and MCDA with the practical need to make operational decisions in disaster response logistics, which is still a topic with limited exploration in the literature.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. MCDA Foundations and VFT-MAVT Modeling

Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA), also known as Multiple Criteria Decision Aid or Multi-Attribute Decision-Making, is a branch of soft operations research that has developed rapidly over the last decades. It provides a family of formal approaches designed to help individuals or groups make structured choices when several, often conflicting, criteria must be considered [

44]. In such situations, intuitive or “gut-feel” judgment is rarely sufficient, and analytical tools become necessary.

MCDA supports decision-making when multiple objectives need to be achieved simultaneously. A typical MCDA intervention follows three main phases: (i) problem structuring, (ii) model building, and (iii) preference modeling and evaluation of the decision alternatives. These phases are not strictly linear; insights gained later may lead analysts to revisit earlier steps [

20].

Several techniques are used during problem structuring (phase 1), such as cognitive mapping [

45], soft systems methodology [

46], and value-focused thinking [

47,

48]. Once the decision situation is clearly defined, the next step is to build an evaluation model. This model normally includes a hierarchy of objectives, attributes to measure their achievement, and the set of alternatives to be compared.

In the next step (phase 2), preferences are modeled by assigning weights and value functions to each criterion. The total value of an alternative a can be represented by an additive model:

where

vi (

a) represents the performance of alternative

a under criterion

i, and

wi reflects the relative importance of that criterion.

The last phase consists of modeling preferences and evaluating the decision alternatives. Score definitions may first be done by eliciting intra-criteria information using a local scale. In this case, the worst alternative is assigned a score of 0 and the best a score of 100. The other alternatives receive intermediate scores that reflect their relative importance between these two endpoints. This procedure must be performed for each criterion.

It is clear that in any evaluation not all criteria have the same weight, so it is desirable to make their relative importance explicit. The simplest way to solve this issue is to define weights within the value tree. Relative weights should be assessed within families of criteria, and the cumulative weight of each criterion is obtained by multiplying its relative weight compared with its siblings and the relative weights of its parent, grandparent, and so on, up to the top of the tree. The outcome of this process will show the best alternative according to the decision-maker’s value judgments. However, this outcome should not be viewed as the end of the analysis. It is simply another step toward a better understanding of the problem [

44].

These approaches form the conceptual foundation of the method proposed in this study, which applies the principles of VFT and Multi-Attribute Value Theory (MAVT) to support the allocation of air rescue units under uncertain disaster conditions.

The proposed decision-support method follows the three-phase MCDA framework 1 and adapts it to the context of air rescue unit allocation.

The decision to use the VFT-MAVT combination is justified by the nature of helicopter allocation problems in disaster situations, where several objectives, crew safety, response time, number of victims rescued, structural risk, and operational conditions, must be considered at the same time.

These criteria have complex trade-off relationships and are often in conflict. As a result, purely optimization-based methods commonly used in air logistics do not adequately reflect the humanitarian and operational values involved. The MCDA approach helps make these trade-offs explicit and allows decisions to be based on transparent and reproducible value structures, aligned with established practices in contexts of high uncertainty.

As evidenced in the literature review, most MCDA applications in humanitarian logistics focus on strategic decisions, such as facility location, resilience assessment, and infrastructure planning. Few models address operational decisions related to aircraft dispatch during the response phase, even though this process is critical for reducing fatalities. The present study addresses an important gap by proposing a multi-criteria model that transparently supports tactical and operational decisions for allocating air rescue units under significant uncertainty.

The integration between VFT and MAVT ensures that the model’s objective structure is not arbitrary, but based on fundamental values recognized in rescue operations, preserving lives, protecting the crew, expanding casualty coverage, and ensuring the operational viability of missions. This process reduces biases from models focused solely on technical performance and reinforces the model’s alignment to operational reality.

Moreover, the proposed model can be integrated into existing decision-support systems used by air operations centers. Its value structure can be updated as institutional guidelines change, and weights can be adjusted to reflect current priorities. This makes the method compatible with real aircraft dispatch processes and supports decisions made under time pressure and incomplete information.

3.2. Decision Context and Data

The following subsections describe the decision context and the data used to construct the MCDA model, including flood characteristics, victim distribution, risk levels, and the operational parameters of the helicopter rescue units.

3.2.1. Flood Scenario

In recent decades, References [

3,

4] indicate an increase in the frequency and severity of floods. These events accounted for about one-third of recorded natural disasters and affected more than 1.5 billion people. The effects associated with global warming, such as sea-level rise, more intense precipitation, and higher river discharges, may increase both the frequency and extent of flooding worldwide. In developing countries, rapid urbanization and the occupation of coastal or river-plain areas by agricultural, residential, and industrial activities also increase vulnerability to flood hazards [

49]. These figures support the use of the flood scenario as a test environment, since floods remain one of the most recurrent and operationally demanding events for aerial rescue missions.

In general, floods can be predicted in advance, except in the case of flash floods. Their impacts include the destruction of houses, crops, livestock, and human life. Floods also pose specific challenges for emergency response because large areas may remain submerged, making coordination extremely difficult. Logistics, transportation, and the distribution of relief goods are often complicated since infrastructure is frequently damaged [

5].

Reference [

50] identified six main types of floods: riverine flooding, flash floods, structural-failure or overtopping floods, urban drainage flooding, mudflows, and coastal flooding and erosion. Among these, riverine and flash floods are the most frequent in disaster-response situations. These events are typically caused by heavy rainfall of extra-tropical or frontal origin, or by large tropical depressions carrying moisture-laden winds that move from maritime to continental areas—for example, seasonal monsoons in Asia or line squalls on the west coast of Africa. The resulting rainfall is usually widespread and intense, and flood levels are strongly influenced by local topography.

Such floods are well documented and useful for analyzing both flood-risk ranges and emergency-response requirements. Their aftermath often involves severe structural damage to bridges, roads, and buildings, leading to the isolation of affected zones, contamination of wells by standing water, and obstruction of drainage paths [

50].

3.2.2. Flood Victims and Risk Levels

Data from the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters [

51], which records all flood disasters in Brazil from 1948 to 2008, were used to estimate the average number of victims. These data were used to obtain representative average values for the construction of simulated scenarios, rather than to represent a specific situation. The severity and distribution of casualties in major floods tend to remain similar over time. This supports their use for modeling and illustration purposes. Each flood event caused, on average, 65 deaths, 104 injuries, and about 9200 homeless people. These values were used to define the number of victims in the simulated decision alternatives.

Victims are classified into four evacuation and treatment priority levels, represented by color codes according to injury severity (Brazilian emergency response protocol): P1 (Red)—critical but recoverable; P2 (Yellow)—severe; P3 (Black)—critical and unrecoverable; and P4 (Green)—minor injuries. For this study, an additional level was included: P5 (Blue)—homeless victims, not injured but requiring evacuation.

Another important aspect is the risk level of the area where victims are located. The Brazilian National Risk Mapping and Management Guidelines [

52] defines four risk levels for structural destruction caused by rainfall or flooding. These levels assume current environmental conditions remain unchanged: R1 (Low)—destructive events are not expected; R2 (Medium)—reduced probability of destructive events; R3 (High)—destructive events are possible; and R4 (Very High)—destructive events are very likely.

This classification was incorporated into the decision model as one of the evaluation criteria, influencing the prioritization of rescue operations and the feasibility of helicopter missions. As a recent study by [

4] shows, the severity and distribution patterns of casualties in major floods remain consistent over time, justifying the use of these values for modeling purposes.

3.2.3. Rescue Units and Safety Parameters

Victim rescue activities are generally classified as Emergency Medical Services (EMS), executed by Rescue Units (RU), whose main objective is to reduce mortality from acute illness or trauma. Achieving this objective depends on the rapid response of a properly staffed and equipped RU, on-scene stabilization of patients, and transportation to a medical facility or a Victim Support Area (VSA) capable of providing definitive care [

53].

The main advantages of helicopter-based medical response include rapid deployment across wide areas, delivery of advanced pre-hospital care, and direct transport of victims to suitable hospitals or support areas. Most HEMS operate 24 h a day with pilots and medical crews on standby, allowing immediate response. When activated early, the helicopter and crew can also assist in the initial organization and management at the disaster site.

In this study, the RU considered is a commercially available helicopter widely used in search and rescue operations. Its technical characteristics, obtained from manufacturer data, were used to define the operational parameters of the model.

Safety is a critical factor in helicopter rescue missions. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) accident database identified three main risk factors in helicopter air ambulance operations: adverse weather conditions, environmental obstructions, and aircraft airworthiness issues [

54].

Recent developments in weather forecasting have improved the ability to translate meteorological data into useful decision-support information [

55]. Therefore, weather conditions are considered a tactical variable in this study, influencing the allocator’s decision to dispatch a rescue unit. Weather conditions at the departure, pick-up, and landing points can restrict or prevent mission completion and affect the probability of success.

In Brazil, the Aeronautical Accident Investigation and Prevention Center (CENIPA), a national agency responsible for flight safety, recommends a pre-flight risk management system known as the SIPAER Risk Management Method (MSGR). This method uses a risk assessment table in which aircraft operators define mission risk levels based on their knowledge, experience, statistics, and operational manuals. The risk table must be updated before each flight according to mission-specific information.

The SIPAER methodology defines five risk levels, Low, Medium, High, Very High, and Unacceptable, each associated with specific operational actions. For example, low-risk missions require no adjustments, while high or very high levels demand risk-reduction measures or authorization from commanding officers. In cases classified as “Unacceptable,” the mission is canceled or escalated to higher authority for decision-making.

The model’s emphasis on safety factors aligns with operational practices, where crew protection is treated as a non-compensatory criterion. In real-world operations, this principle often prevails over marginal gains in the number of victims rescued. The inclusion of these criteria in the MCDA reflects this institutional priority and brings the model closer to operational practice.

3.2.4. The Helicopter Emergency Medical Service Operational Process

The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) and Rescue Unit (RU), jointly referred to as the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS), follow a standardized operational sequence during disaster response. The HEMS process begins when an emergency call is received and ends when the helicopter returns to its base after completing the mission.

The total service time represents the duration between the call reception and the unit’s return to base. It includes several intermediate phases such as dispatch delay, travel to the scene, time spent on-site, transport of victims to a medical facility or support area, and repositioning. This total time, referred to as Total Flight Time (T9–T1) in the original model, is used in this study as an indicator of mission duration and response efficiency.

The HEMS process representation used in this study follows the operational flow adopted by aeronautical command centers. This alignment allows the proposed model to be incorporated, in the future, into existing decision-support modules.

3.3. Data Simulation

The purpose of this step is to simulate multiple rescue scenarios for all locations, including their corresponding weather conditions. Some options are discarded due to infeasibility, while the remaining ones are evaluated according to their probability of mission success.

As described in the previous subsections, several factors can affect the success of a rescue mission and, consequently, the decision to activate it.

Figure 1 presents the simulated scenario.

The simulated scenario represents a set of flooded areas already classified by risk level, each containing a known number of victims in different health conditions. These areas are associated with defined weather conditions and are located at known distances from both VSAs and HEMS bases. The locations of HEMS bases and the operational capacities of the rescue units are also specified.

Because real-world disaster situations involve dynamic and uncertain information, the simulation assumes that all parameters remain static during the analysis. The management center is assumed to have all resources temporarily unavailable (in operation) for a particular period, during which new information is accumulated and processed until a unit becomes available.

Since the focus of this study is the decision-making process, all probabilities and numerical parameters were generated through simulation rather than collected from real data. These values do not represent any specific case study but serve to demonstrate the application of the proposed model.

Several variables influence the probability of mission success, including weather conditions, crew experience and training level (such as total flight hours, recent mission type, and idle time), crew fatigue, and helicopter maintenance condition. The probability of no weather-related accident is directly linked to the severity of adverse weather, while the probability of no operational accident is derived from the SIPAER Risk Management Method (MSGR).

The expected number of rescued victims corresponds to a discrete random variable, computed as the total number of victims multiplied by the probability of success for each area, as presented in Equation (2):

Each decision alternative represents a set of possible flight routes connecting rescue bases, flooded areas, and victim support areas. For example, Alternative A assumes that the HEMS based at Base 1 rescues victims from Areas 13, 11, 10, 9, and 8, transporting them to VSA 1. This operation requires approximately 4794 min of total flight time, with an 81% probability of no weather-related accident and a 100% probability of no crew fatalities (low-risk level). The expected number of rescued victims is 161, calculated from the sum of success probabilities for each area.

In contrast, Alternative I assumes that the HEMS based at Base 2 rescues victims from Areas 4, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, and 3, transporting them to VSA 3. This mission requires 2824 min of total flight time, faces more adverse weather conditions, and has a 75% probability of no weather-related accident and only a 10% probability of no crew fatalities (very high-risk level). Despite the greater risk, this configuration results in an expected 212 victims rescued, as the targeted areas are closer to the base.

The simulation assumptions were defined to maintain consistency between parameters and reflect operational conditions used in real-life situations. Probabilities, distances, flight times, and risk levels were calibrated based on HEMS literature, regulatory parameters, and exploratory interviews with pilots and aeromedical physicians. Although it does not represent a real-world case, the simulation reproduces realistic conditions that allow for the evaluation of the MCDA model’s behavior.

The simulated scenarios represent systematic combinations of flooded areas, operational bases, VSAs, and weather conditions. Each alternative corresponds to a viable operational configuration for rescue missions, respecting aircraft autonomy, safety limits, and transport capacity. The simulation does not aim to predict real outcomes, but to provide a controlled environment to evaluate the VFT–MAVT approach in a highly complex context. This procedure is consistent with the MCDA literature in emergency management, where models are often tested in synthetic scenarios before being validated with real data.

3.4. Definition of Objectives and Criteria Weights

The fundamental and means objectives were derived from the literature on disaster logistics and air rescue operations. The hierarchy was structured following the Value-Focused Thinking (VFT) procedure proposed by [

23], considering typical operational priorities of rescue coordination centers.

To clearly explain how this structure was built, the conceptual foundation used to derive the model’s objectives and criteria is presented below.

The application of VFT results in the construction of a Fundamental Objectives Hierarchy, which organizes end-objectives and means-objectives in a way that reflects the decision-maker’s values. This tool is essential for the use of MAVT, as it guides the definition of measurable attributes, value functions, and criterion weights. The resulting structure reflects both the operational priorities of HEMS missions and the values identified in the literature and the analyzed context.

The construction of the objectives followed a three-step process: (i) identifying the core values of air rescue operations, such as crew safety, preservation of lives, time efficiency, and operational feasibility; (ii) translating these values into fundamental and intermediate objectives; and (iii) defining measurable attributes to represent each objective in the model.

3.5. Criteria Weight Assessment

The weights of the criteria were obtained with a structured process to define their relative importance, following common MAVT practice. The procedure used three sources. First, operational principles from HEMS, where crew safety is treated as a non-compensatory element. Second, aviation safety documents that set clear limits for risk acceptance. Third, trade-offs described in the MCDA literature on humanitarian logistics and disaster response.

The process involved: (i) Grouping criteria into families: safety (probability of meteorological and operational accidents), operational efficiency (total mission time), and humanitarian benefit (expected rescued victims); (ii) Assessing relative importance within each family through qualitative comparisons; (iii) Assigning global weights at the level of fundamental objectives, reflecting the institutional priority of minimizing fatalities, particularly crew-related ones.

The numerical values resulting from this process are presented in

Section 4. Here, the focus is on emphasizing that weight elicitation was not ad hoc: it followed a consistent logic aligned with real disaster-response practices and MCDA guidelines.

3.6. Value Functions Construction

Value functions were defined to allow all criteria to be evaluated on a common scale:

Quantitative criteria (e.g., mission time): linear normalized functions (0–100), using minimum and maximum observed values.

Safety-related probabilities: concave or convex increasing functions to represent aviation risk aversion, where small reductions at high safety levels produce greater loss of value.

Categorical risk levels (R1–R4): ordinal values consistent with national risk-mapping guidelines.

All functions use 0 as the worst acceptable condition and 100 as the best observed condition. This normalization facilitates interpretation and communication with decision-makers while ensuring consistency for the additive MAVT model.

Table 1 summarizes the criteria included in the MAVT model, their operational meaning, measurement units, and how they were calculated or obtained.

Defining the criteria, their units, and the value functions gives the operational basis needed to apply the VFT–MAVT model. These elements shape how each alternative is judged and make the preferences and constraints of HEMS operations explicit. After specifying the attributes and the process used to obtain the weights, the next step is to apply the multi-criteria model to the simulated alternatives. The results appear in

Section 4.

4. Results

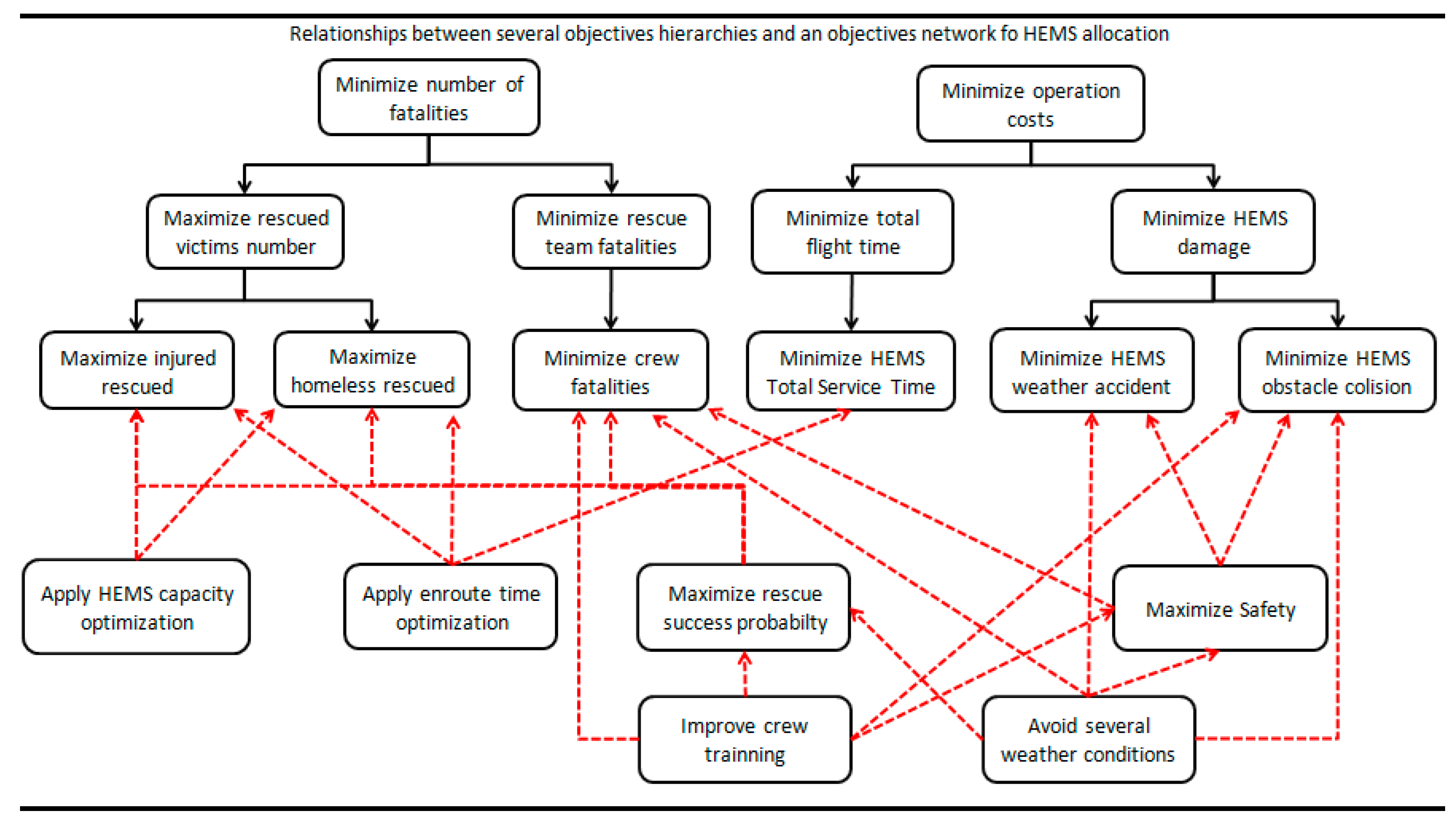

The application of the VFT Method in the decision context of allocating HEMS to rescue flood victims gave as outcome the fundamental objectives hierarchy, as seen in

Figure 2.

The application of the VFT procedure led to the identification of four fundamental objectives for the decision context of allocating HEMS units to flood rescue operations. Each objective was associated with a measurable attribute used to evaluate the alternatives:

Maximize the number of rescued victims: measured by the expected number of victims successfully rescued, considering the probability of mission success;

Maximize operational safety—represented by the overall mission risk level;

Minimize HEMS damage—expressed by the probability of weather-related accidents;

Minimize total service time—represented by the total flight duration in minutes.

After defining the objectives and their attributes, the criteria were organized into a hierarchical structure with two main goals: (i) minimize operation costs; and (ii) minimize number of fatalities.

At the upper level, “Minimize number of fatalities” received 90% of the total importance, while “Minimize operation costs” received 10%. Within each group, the weights were distributed proportionally among the associated criteria. Under operational costs, “Minimize total service time” and “Minimize HEMS damage” were weighted at 5% and 95%, respectively. Under number of fatalities, “Minimize crew fatalities” and “Maximize rescued victims” were weighted at 99% and 1%, respectively.

These hierarchical weights were then aggregated to obtain the overall contribution of each criterion to the final value function, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 3 presents the simulated alternatives, labeled A to I, which represent different operational configurations for allocating HEMS units to flooded areas. Each alternative corresponds to a distinct combination of helicopter bases, flight routes, and victim support areas, generated to reflect variations in total flight time, weather exposure, and expected number of rescued victims. These scenarios allow the decision-maker to compare the performance of multiple feasible rescue strategies under similar environmental and operational condition.

The values presented in

Table 3 are derived from simulated scenarios constructed from realistic parameters extracted from operational manuals, the literature, and safety protocols. Simulation was used in this study because consistent observational data for multiple simultaneous missions under disaster conditions are rarely available. The goal of the simulation is not to reproduce a specific real-world case, but to create a set of plausible alternatives that illustrate how the model operates and assess its ability to support decisions under uncertainty.

The local and global weights were then aggregated to calculate the overall value score for each alternative. Alternatives A, B, and C obtained the highest overall scores, 97.8, 93.0, and 90.9, respectively, indicating superior performance according to the decision-maker’s preferences.

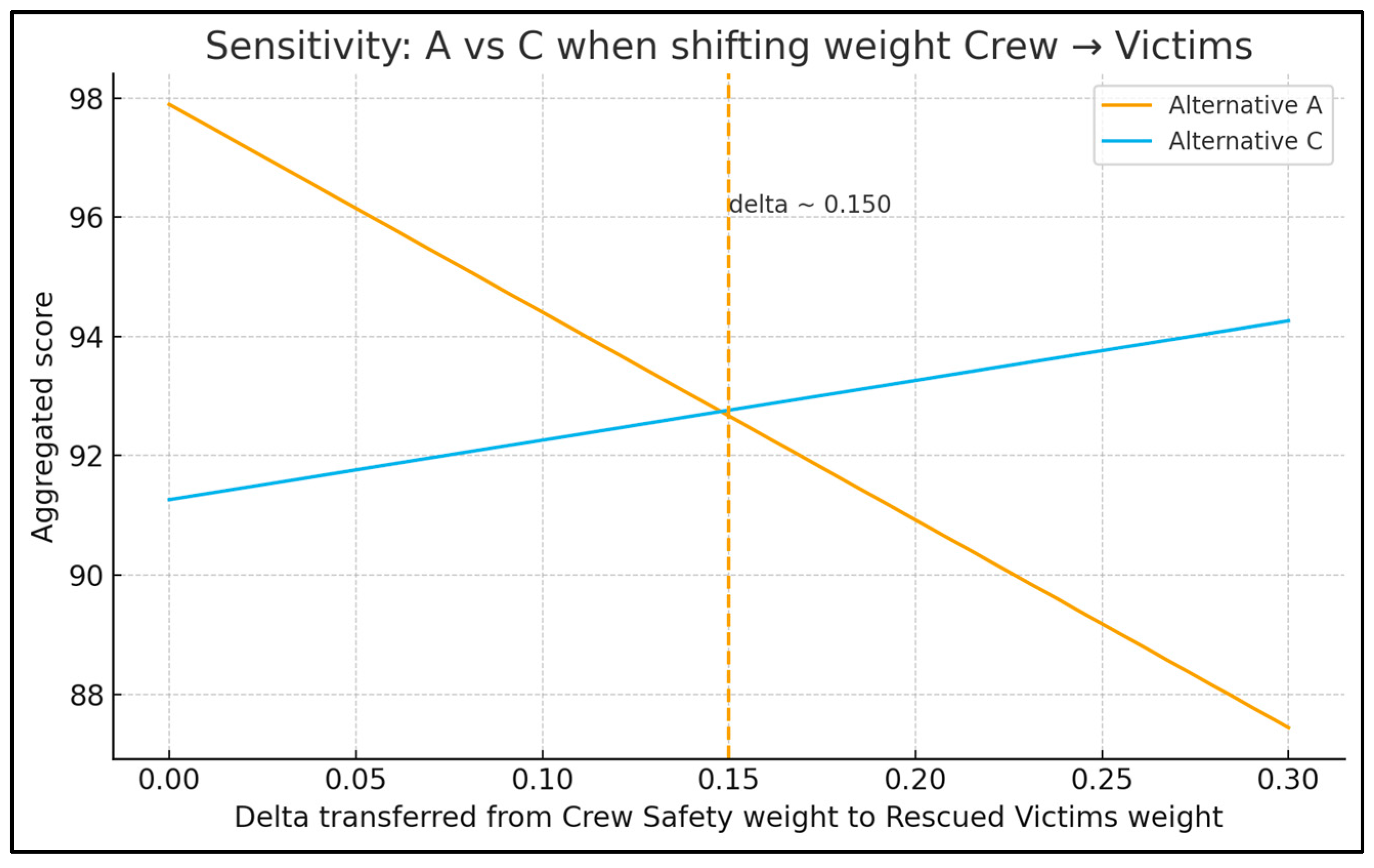

A sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying criteria weights while keeping the value scales unchanged, as shown in

Figure 3.

The analysis indicates that Alternative C surpasses A only when at least ~0.15 of global weight is transferred from crew safety to rescued victims. The ranking was also tested under adverse-weather scenarios.

5. Discussion

The results showed that the proposed model was able to compare different alternatives for allocating air rescue units. In the explored example, Alternative A was identified as the most appropriate. For the decision-maker in question, who has a strong conservative bias, high priority was given to operational safety.

The predominance of safety criteria observed in this result aligns with international studies on HEMS operations. These studies show that most fatal accidents are associated with decisions made under pressure, especially when adverse weather conditions are underestimated. Identifying the most conservative alternative as the preferred option is therefore consistent not only with the decision-maker’s profile but also with widely documented empirical evidence.

The structuring phase was carried out using the VFT approach, which led to the identification of the fundamental objectives and their organization into a hierarchical structure. This Fundamental Objectives Hierarchy represents the decision-maker’s values and clarifies how the objectives relate to each other. This hierarchy synthesizes the decision-maker’s core values in the context of allocating HEMS units during flood response operations. It provides the analytical foundation for assigning weights, defining value functions, and subsequently aggregating the criteria.

The distribution of weights reflects the priorities observed in real response operations, in which the preservation of lives, especially crew lives, is treated as a paramount objective. This prioritization is consistent with rescue aviation guidelines, operational safety standards, and specialized literature, which emphasize that missions involving high risk to the crew should be avoided, even when they may result in a larger number of rescued victims.

This weighting structure emphasizes mission safety as the dominant factor in the decision process, while still accounting for operational efficiency. The 90% weight assigned to “Minimize the number of fatalities” expresses the operational principle that crew safety is a necessary condition for mission continuity and for the sustainability of subsequent operations. The 10% assigned to operational cost indicates that efficiency is relevant, but should not override safety in high-risk contexts. Although these weights can be adjusted for other decision-maker profiles, in this study they were defined to represent a conservative scenario aligned with real HEMS coordination practices.

The results show that mission-safety criteria dominate the final ranking. Operational time and the number of rescued victims have a smaller effect on the aggregated value. The MCDA process identified Alternative A as the most preferred option, reflecting the decision-maker’s value structure and emphasizing operational safety. However, this outcome should not be interpreted as a final decision but as an analytical step toward a better understanding of the problem. Alternatives B and C also present competitive performance and could be considered viable options depending on the decision-maker’s tolerance for risk and operational priorities.

In practice, these alternatives may be discussed among stakeholders, such as the resource allocator, HEMS crew, and operational commanders, to determine whether a slightly higher level of risk (for example, 90–95% safety) could be acceptable in exchange for rescuing a larger number of victims.

The interpretation of the results should consider that the model explicitly prioritizes operational safety, which is why alternatives with a higher probability of accidents, even when they rescue more victims, receive lower aggregate values. This behavior is consistent with the adopted weighting scheme and illustrates the model’s usefulness in making explicit the trade-offs between saving more victims and accepting greater risk for the crew. In real-world contexts, these trade-offs are discussed among different actors involved in the operation, and the model provides a structured basis to support this deliberative process.

Results showed that the ranking is robust. For instance, alternative C only surpasses A when at least ~0.15 of the global weight is transferred from crew safety to rescued victims. The sensitivity analysis included one-way variations and a directed trade-off between crew safety and rescued victims. The ranking was also tested under adverse-weather scenarios. The analysis indicates that the top alternative remains stable under moderate preference shifts.

Overall, the results obtained in this study demonstrate that the multi-criteria framework used is able to clearly distinguish between operationally viable alternatives and those that, although rescuing more victims, present risk levels incompatible with HEMS safety standards.

The strong dominance of safety criteria, reflected in the weights and confirmed by the sensitivity analysis, meant that alternatives with a higher probability of accidents were penalized, even when associated with shorter mission times or a greater number of victims rescued. This confirms that the VFT–MAVT approach was successful in translating structural decision values into quantitative results that remain aligned with the decision-maker’s priorities.

Furthermore, the results suggest that decisions involving trade-offs between risk and humanitarian coverage can only be adequately evaluated when safety criteria are explicitly modeled as nearly non-compensatory. The comparison between close alternatives (A, B, and C) shows that small variations in risk levels produce large effects on the added value, reinforcing the importance of incorporating realistic preference structures. This type of behavior would not be captured in purely optimizing models, highlighting the usefulness of MCDA in disaster response scenarios.

However, in a dynamic environment such as humanitarian operations, priorities can change, with greater risk tolerance or the need to increase the number of rescued victims. In this context, the proposed method allows visualizing that alternatives B and C can also be considered. The model proved to be robust, as indicated by the results of the sensitivity analysis.

This flexibility is essential in real-world contexts, as air rescue missions often require rapid adjustments in priorities. The literature shows that command teams may accept higher levels of risk to maximize life savings in extreme scenarios. The model supports this type of analysis by showing how small shifts in preferences can alter the priority order among feasible alternatives.

The main contribution of this study is to demonstrate that the combination of the VFT and MAVT approaches allows the structuring and measurement of values and priorities in a hierarchical and traceable way, even in environments characterized by complexity and uncertainty. This contribution fills an important gap in the literature, as most studies on resource allocation in disasters rely on purely optimization-based models. These models assume linear trade-offs between criteria and do not adequately represent non-compensatory objectives such as operational safety.

By no means is the proposed method intended to replace human judgment, but rather to offer a decision-support tool, especially for operators with less experience. In addition, the method allows greater accountability, by promoting transparency and communication among different stakeholders. The transparency provided by the model is consistent with recent governance recommendations in humanitarian operations, which emphasize the importance of documenting and justifying critical decisions. This expands the method’s potential not only as an operational tool, but also as an instrument for training, standardization, and auditing.

In practical terms, the methodology can be easily adapted to other types of missions, by adjusting the criteria and weights according to specific operational priorities. Thus, the model proves to be flexible and replicable, maintaining methodological consistency and practical applicability. This adaptability makes the model compatible with different operational doctrines, civilian, military, or mixed, and facilitates its integration with computer-aided dispatch systems, mission simulators, and institutional protocols.

Compared to traditional approaches based solely on time optimization or on maximizing the number of victims assisted, the VFT–MAVT model presents a clear advantage by making explicit the trade-offs between safety, efficiency, and humanitarian benefit. The results show that the proposed approach not only identifies the alternative with the best overall performance, but also avoids solutions that would be operationally impractical or unsafe, thereby increasing the reliability of the decision.

The results also have direct implications for the formulation of operational policies. The resulting hierarchical structure can be used as a basis for dispatch protocols, contributing to the standardization of decisions in high-pressure situations. Additionally, the weights and value functions can serve as institutional guidelines for training new allocators, aligning teams on operational priorities, and establishing formal limits of acceptable risk. In this way, the model becomes an instrument that supports the governance and consistency of HEMS operations.

Despite its promising results, the study presents some limitations that must be recognized. The assigned weights should not be seen as absolute truths, but as the quantification of the main values of a decision-maker. Another aspect is the validation of the proposed model. It is recommended to validate the model in practical, comparing the performance of assisted decisions with traditional human decisions, in order to evaluate its actual impact on the efficiency and safety of response operations.

Another important limitation is the use of simulated data. Although the parameters were defined within realistic operational ranges, the absence of complete observational data restricts the generalization of the results. This type of constraint is common in HEMS studies, where detailed mission records are often incomplete or unavailable. Future research could incorporate historical data to calibrate probabilities and value functions more precisely, improving the realism and applicability of the model.

For future research, it is suggested to integrate MCDA with simulation or optimization models, combining the value structure with computational techniques to generate more automated solutions. In addition, hybrid models capable of operating in near real-time could incorporate weather forecasts, aircraft condition data, and dynamic crew availability. Participatory weight elicitation methods involving multiple decision-makers are also recommended, as they would capture different institutional priorities and increase the robustness of the model.

6. Conclusions

Disaster operations management involves an almost infinite number of problem situations occurring in different locations, with varying scenarios, factors, and uncertainties. These issues must be properly managed to save lives throughout the disaster cycle, which includes mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery phases.

Recent literature highlights that the response phase is the most sensitive stage for interventions. It has a direct impact on preserving lives, especially when rapid deployment and action in highly degraded environments are required. The decision to study the allocation of HEMS responds to a practical demand observed in different countries and in various humanitarian aid contexts.

After a disaster occurs, the response phase becomes the main opportunity to save affected populations. Helicopters play a key role in this stage, reaching and rescuing victims in otherwise inaccessible areas where rapid action is required. This phase is characterized by search and rescue operations involving victims with different health conditions, areas with distinct risk levels, uncertain weather conditions, and limited resources and time to save lives.

Despite the relevance of these operations, the literature reveals a gap in structured models that integrate humanitarian, aeronautical, and logistical factors. This study contributes by proposing an approach that combines principles of VFT and MAVT to organize and evaluate alternatives under multiple conflicting criteria.

The allocation of air rescue units, however, requires situational awareness to avoid accidents, delays, and consequently, further fatalities. These conditions are often uncertain, and their analysis and trade-offs must be well managed to ensure mission success. This is a non-trivial problem. These trade-offs have a conflicting nature. Saving more victims versus accepting greater risk, or reducing time versus limiting weather exposure, shows that one-dimensional approaches are not sufficient to cover all dimensions. Multi-criteria models can capture this reality and promote more justifiable and auditable decisions.

The resource allocator in a disaster management center has a crucial role in this context, as he decides how, when, and where to deploy rescue units to save as many people as possible. Due to the diversity of situations faced, experience becomes one of the main factors influencing judgment and the selection of alternatives. However, because of operational and economic constraints, the allocator is not always the most experienced operator available. This situation can make it difficult to identify the best, or even a reasonably good, option for allocating rescue units. This scenario reinforces the need for tools that reduce the exclusive reliance on individual experience and promote more standardized decision-making, especially in environments with high operator turnover or under strong time pressure.

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methodologies, particularly the Multi-Attribute Value Theory (MAVT), were presented as powerful tools to support decision-making in helicopter emergency medical service allocation. This process aims to reduce experience gaps among decision-makers and to make choices faster, more accurate, and more consistent than traditional methods. By translating operational values into formal decision structures, the model improves transparency, supports clear communication between teams, and can be incorporated into computer-based dispatch support systems, expanding its practical utility.

Despite the contributions of this study, some limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the analysis is based on simulated data, defined within realistic operational ranges, but not calibrated with data from real missions. This limits the direct generalization of the results. Furthermore, the weights used reflect the preferences of a specific decision-maker profile, with a more conservative stance, and should not be interpreted as valid for all contexts. Future studies could address these limitations by validating the model with historical or operational data. They could also incorporate participatory weight elicitation involving different stakeholders and integrate the MCDA framework with simulation or optimization models. These extensions could support decision-making in more dynamic environments, considering, for example, weather variations, resource availability, and changes in mission priorities.

This paper proposed a methodology to support air rescue unit allocation decisions during the disaster response phase. The MCDA process, starting from problem structuring through Value-Focused Thinking (VFT) and progressing to the alternative evaluation based on MAVT, successfully achieved its objective. The outcomes indicated a consistent and transparent decision-support process capable of revealing the trade-offs that typically remain implicit in this type of operational context. Overall, the proposed methodology shows that structured value-based decision support can enhance the transparency, consistency, and operational safety of HEMS allocation during disaster response. By translating fundamental priorities into measurable criteria and providing a replicable evaluation framework, the model offers a practical contribution to both researchers and practitioners involved in emergency operations management.