Blockchain Technology and Maritime Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1. What are the main areas of research on blockchain relating to logistics in the supply chain?

- Q2. What are the primary challenges and barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in maritime logistics?

- Q3. What key factors drive blockchain adoption in maritime logistics?

2. Research Context and Literature Review

2.1. Logistics in Supply Chain

2.2. Maritime Logistics

2.3. Blockchain Technology

2.4. Prior Reviews and What They Miss (Maritime-Specific Gap)

2.5. Theoretical Lenses Used in This Review (TOE, Institutional Theory, RBV) and How They Are Operationalized

2.6. Maritime Legal–Regulatory Constraints and Trade Documents (eBL, Smart Contracts)

2.7. Research Gaps and Contributions of This Review

3. Methods

3.1. Search Stage

3.2. Selection Stage

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.5. Study Quality Appraisal

3.6. Bibliometric Mapping Configuration and Robustness Checks

3.7. Thematic Coding and Derivation of the Seven Research Fields

4. Results

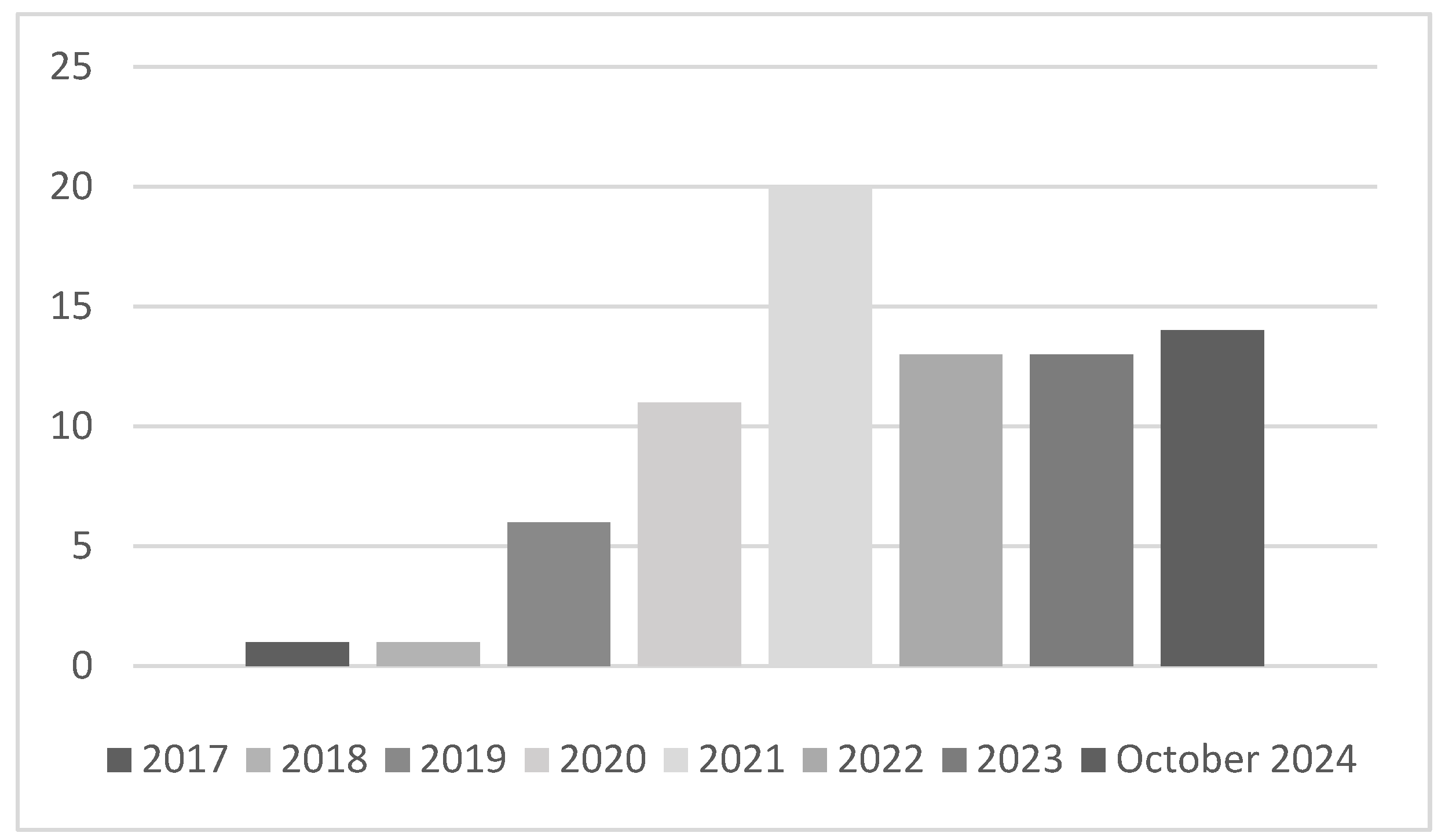

4.1. Articles by Time

4.2. Articles by Journal

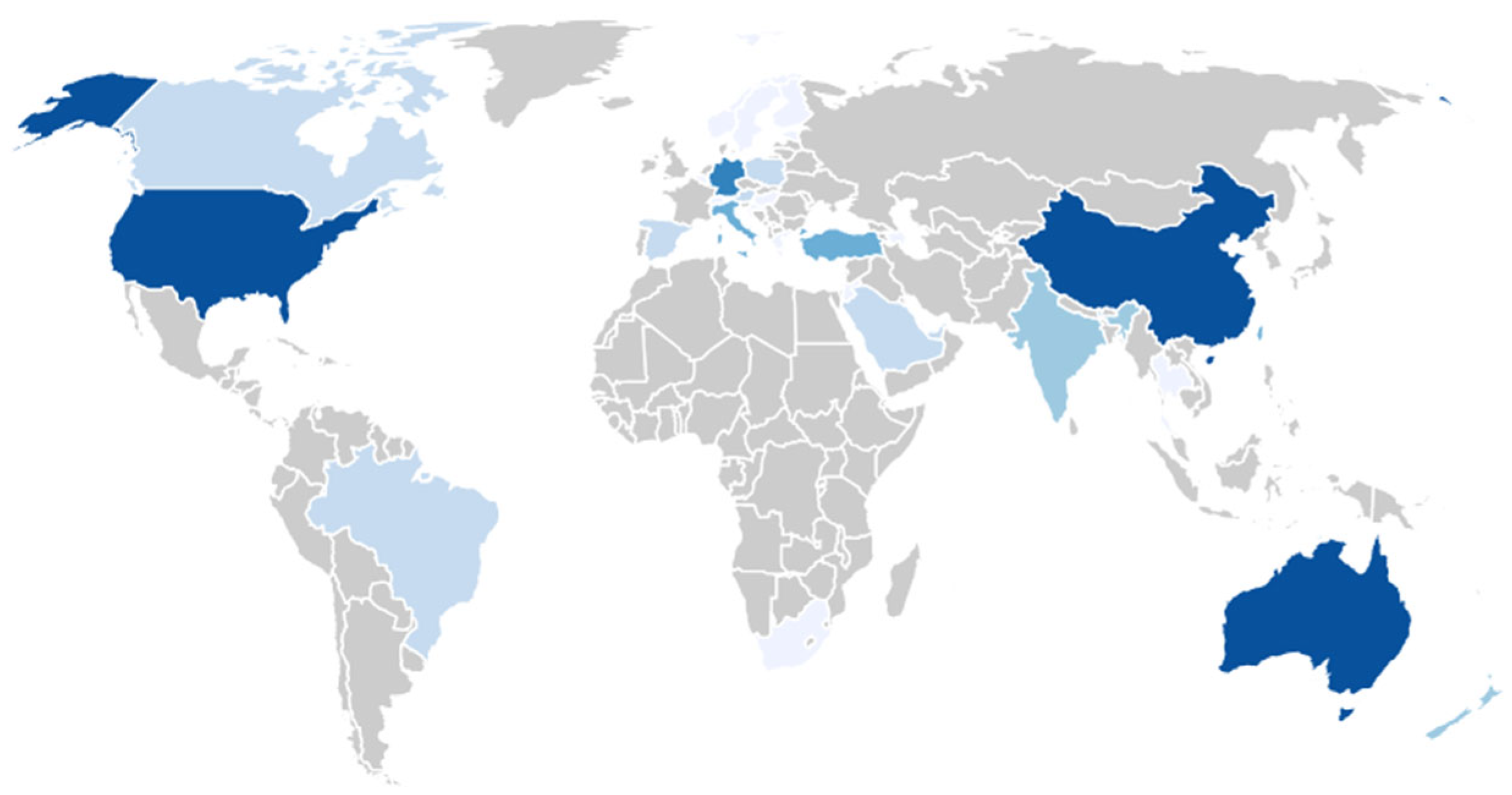

4.3. Articles by Region

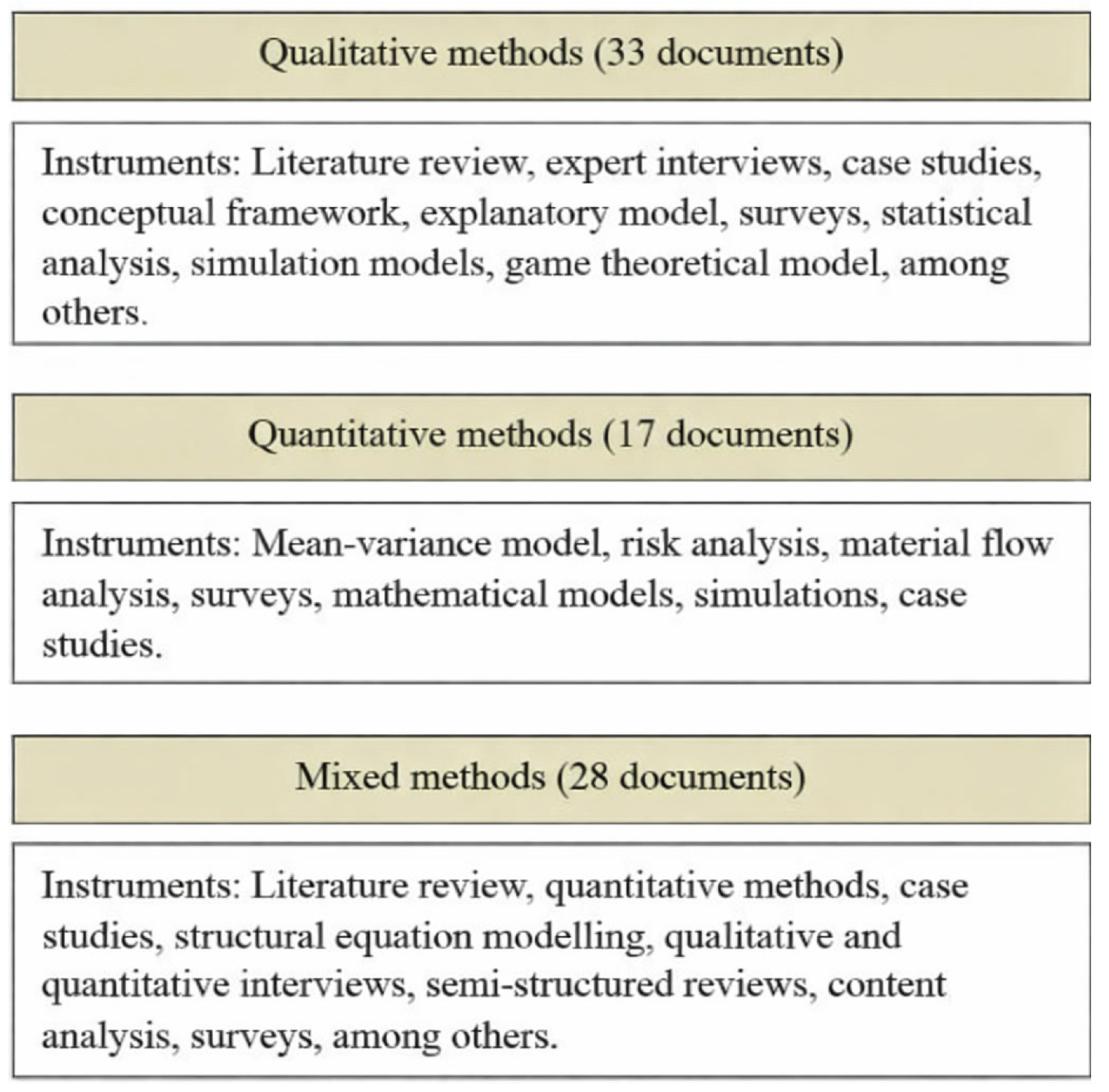

4.4. Articles by Methodology

5. Discussion

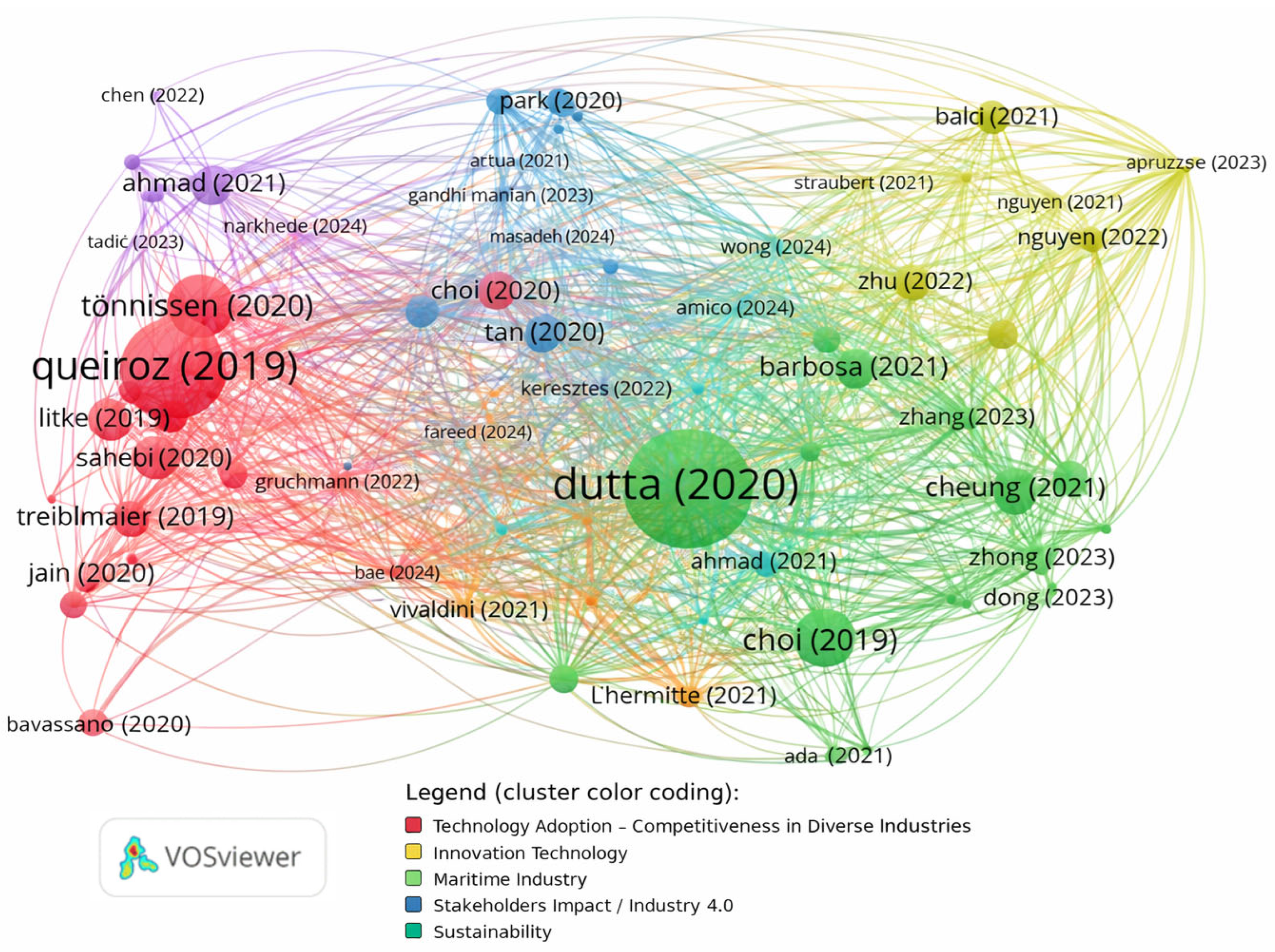

- RQ1. What are the main areas of research on blockchain relating to logistics in the supply chain?

5.1. Red Cluster: Technology Adoption-Competitiveness in Diverse Industries (20 Documents)

- Maritime Logistics and Global Trade—Supply chain visibility, regulatory compliance, fraud prevention.

- Retail and Consumer Goods—Product authentication, consumer trust, ethical sourcing.

- Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare—Drug traceability, regulatory compliance, data security.

- Financial Services and Banking—Fraud prevention, smart contracts, cross-border transactions.

- Sustainability and Circular Economy—Carbon footprint tracking, sustainable sourcing, green logistics.

- Automotive and Manufacturing Supply Chains—Real-time component tracking, quality assurance, smart-contract automation.

5.2. Green Cluster: Innovation Technology (16 Documents)

5.3. Yellow Cluster: Maritime Industry (12 Documents)

5.4. Purple Cluster: Stakeholders Impact Industry 4.0 (10 Documents)

5.5. Blue Cluster: Sustainability Blue Cluster: Sustainability

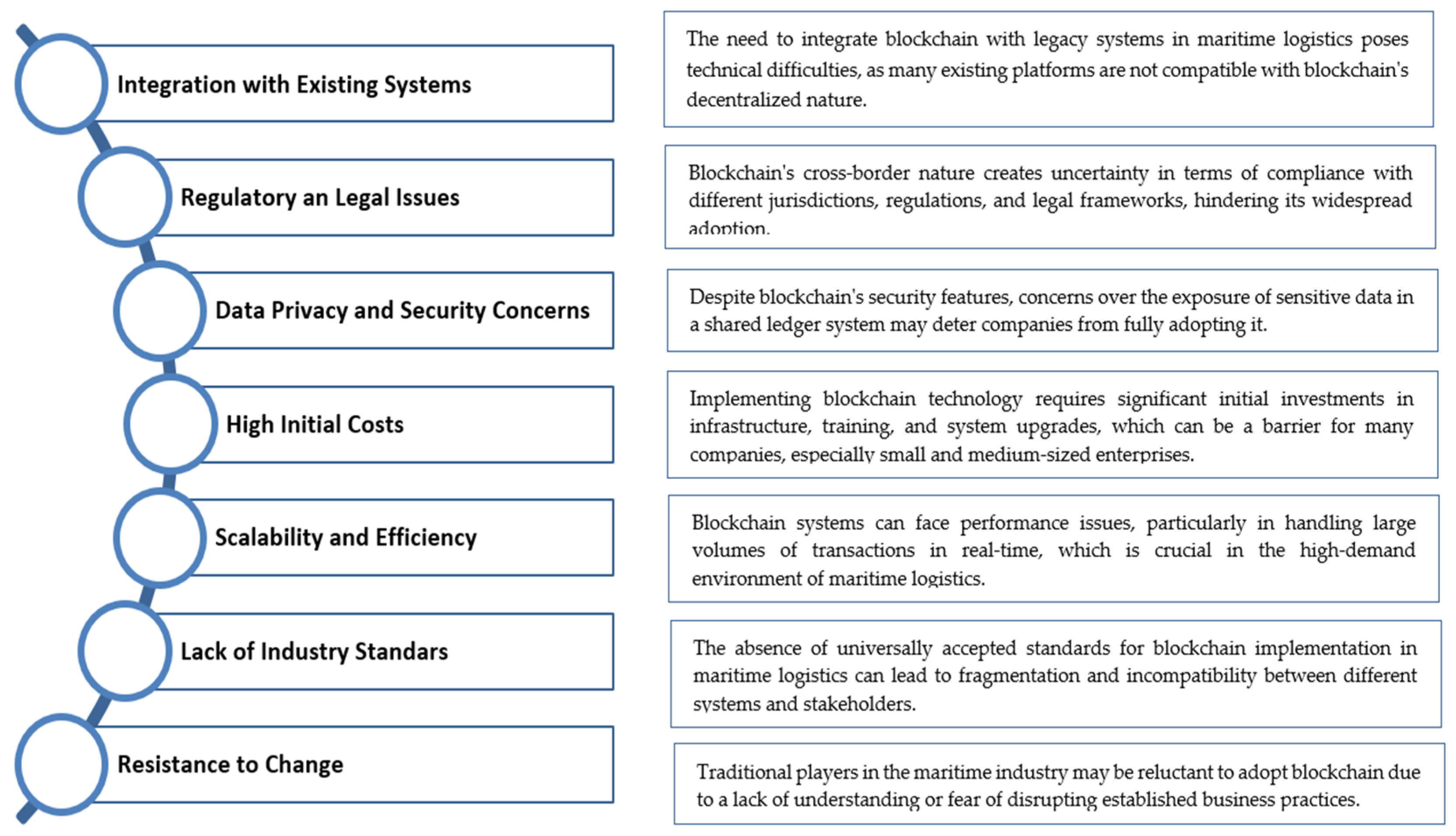

- RQ2. What are the primary challenges and barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in maritime logistics?

5.6. TOE—Technological Context: Interoperability, Standards, Cybersecurity, Smart Contracts

5.7. TOE/RBV—Organizational Context: Capabilities, Readiness, Resistance, ROI Governance

5.8. TOE/Institutional—Environmental Context: Regulation, eBL Recognition, Customs/Ports Gatekeeping, Consortia Diffusion

5.9. Implications for IBAF: What It Explains Well vs. What It Omits

5.10. Theory-Guided Synthesis of Barriers, Drivers, and Adoption Mechanisms for Blockchain in Maritime Logistics and Linkage to the IBAF

- RQ3. What key factors drive blockchain adoption in maritime logistics?

- Cases such as TradeLens, which have been built by Maersk and IBM, show how blockchain enables real-time visibility across the global shipping ecosystem.

- It has been identified from studies that blockchain smart contracts reduce the transaction costs by removing the middlemen and making document verification more automatic [156].

- IoT and blockchain integration for real-time cargo tracking enhance port operations efficiency by minimizing avoidable demurrage payment [155].

- Lack of regulatory clarity in many jurisdictions hinders blockchain implementation [56].

- The maritime industry is highly fragmented, making global regulatory harmonization difficult.

5.11. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). IMO. 2023. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Cheung, K.-F.; Bell, M.G.H.; Bhattacharjya, J. Cybersecurity in logistics and supply chain management: An overview and future research directions. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 146, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peronja, I.; Lenac, K.; Glavinović, R. Blockchain technology in maritime industry. Pomorstvo 2020, 34, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnissen, S.; Teuteberg, F. Analysing the impact of blockchain-technology for operations and supply chain management: An explanatory model drawn from multiple case studies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 101953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR). 2017. Available online: https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts/ecommerce/modellaw/electronic_transferable_records?utm_source= (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- UK Parliament. Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/38/contents?utm_source= (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA). Booking and Bill of Lading Standards—Adoption Guide. 2025. Available online: https://dcsa.org/standards/booking/adoption-guide-booking-and-bill-of-lading?utm_source= (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Dutta, P.; Choi, T.-M.; Somani, S.; Butala, R. Blockchain technology in supply chain operations: Applications, challenges and research opportunities. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 142, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litke, A.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Varvarigou, T. Blockchains for Supply Chain Management: Architectural Elements and Challenges towards a Global Scale Deployment. Logistics 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Bai, C.; Sarkis, J. Blockchain Technology and Supply Chains: The Paradox of the Atheoretical Research Discourse. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, M.; Korchagina, E. Applying Blockchain in the Modern Supply Chain Management: Its Implication on Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Xue, W.; Li, Y. Technology-Driven Logistics and Supply Chain Management for Societal Impacts. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 185, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-Y.; Yue, W.L.; Taylor, M.A.P. The Role of Transportation in Logistics Chain. Proc. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2005, 5, 1657–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, J.T.; DeWitt, W.; Keebler, J.S.; Min, S.; Nix, N.W.; Smith, C.D.; Zacharia, Z.G. Defining Supply Chain Management. J. Bus. Logist. 2001, 22, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, A.; Croucher, P.; Baker, P. The Handbook of Logistics and Distribution Management: Understanding the Supply Chain, 5th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Trade and Development Report 2020: From Global Pandemics to Prosperity for All: Avoiding Another Lost Decade; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/trade-and-development-report-2020 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Alnipak, S.; Toraman, Y. Analysing the Intention to Use Blockchain Technology in Payment Transactions of Turkish Maritime Industry. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 2103–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopford, M. Maritime Economics, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marenković, S.; Tijan, E.; Aksentijević, S. Blockchain Technology Perspectives in Maritime Industry. In Proceedings of the MIPRO 2021, Opatija, Croatia, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Yli-Huumo, J.; Ko, D.; Choi, S.; Park, S.; Smolander, K. Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology?—A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.-N.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Blockchain Challenges and Opportunities: A Survey. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2018, 14, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holotiuk, F.; Moormann, J. The Impact of Blockchain Technology on Business Models in the Payments Industry. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI 2017), St. Gallen, Switzerland, 12–15 February 2017; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2017/track09/paper/6/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Risius, M.; Spohrer, K. A Blockchain Research Framework: What We (Don’t) Know, Where We Go from Here, and How We Will Get There. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.; Avital, M.; Rossi, M.; Thatcher, J.B. Blockchain Technology in Business and Information Systems Research. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. Blockchain: Blueprint for a New Economy; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://books.google.com.mx/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4vFiBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT11&dq=wan,+M.+Blockchain:+Blueprint+for+a+New+Economy%3B+&ots=Qhn9fDFKMI&sig=_Vh06cGZ3Qb_6Xh_bgCtRpZbhUY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Francisco, K.; Swanson, D. The Supply Chain Has No Clothes: Technology Adoption of Blockchain for Supply Chain Transparency. Logistics 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Spencer, M.K. Exploring the Effects of Extrinsic Motivation on Consumer Behaviors in Social Commerce: Revealing Consumers’ Perceptions of Social Commerce Benefits. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Lejia, S. Blockchain Technology and Its Relationships to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Simske, S.; Treiblmaier, H. Blockchain Technologies in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Review. Logistics 2021, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, B.; Bartsch, D.; Herwig, W. Application of Blockchain Technology in Logistics and Supply Chain Management—Insights from a Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2021, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneis, M.; Winkler, H. Value Proposition Assessment of Blockchain Technology for Luxury, Food, and Healthcare Supply Chains. Logistics 2021, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argumedo-García, M.; Salas-Navarro, K.; Acevedo-Chedid, J.; Ospina-Mateus, H. Bibliometric Analysis of the Potential of Technologies in the Humanitarian Supply Chain. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Soh, Y.S.; Loh, H.S.; Yuen, K.F. The Key Challenges and Critical Success Factors of Blockchain Implementation: Policy Implications for Singapore’s Maritime Industry. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 104265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, S.; Lam, J.S.L. Blockchain Adoptions in the Maritime Industry: A Conceptual Framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 48, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irannezhad, E. The Architectural Design Requirements of a Blockchain-Based Port Community System. Logistics 2020, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, G.; Surucu-Balci, E. Blockchain Adoption in the Maritime Supply Chain: Examining Barriers and Salient Stakeholders in Containerized International Trade. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 156, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, M.; Tijan, E.; Žgaljić, D.; Aksentijević, S. Improving Maritime Transport Sustainability Using Blockchain-Based Information Exchange. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Wang, Y.; Pettit, S.; Abouarghoub, W. Blockchain Application in Maritime Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2024, 51, 1062–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhen, L. Blockchain Technology in Maritime Supply Chains: Applications, Architecture and Challenges. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 3547–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Wood, L.; Wang, J.; Duong, L. Blockchain Adoption in the Port Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2431650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.; Ouzayd, F.; Ech-cheikh, H. Blockchain Technology in Maritime Single Window and Port Community Systems: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2025, 18, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiulin, S.; Reinau, K.H.; Hilmola, O.-P.; Goryaev, N.; Mostafa, A. Blockchain-Based Applications in Shipping and Port Management: A Literature Review towards Defining Key Conceptual Frameworks. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2020, 30, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Irannezhad, E. Performance Analysis of LogisticChain: A Blockchain Platform for Maritime Logistics. Comput. Ind. 2024, 154, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S.M.M.; Hoseini, S.F.; Gholami, H.; Kananizadeh-Bahmani, M. A Three-Stage Digital Maturity Model to Assess Readiness for Blockchain Implementation in the Maritime Logistics Industry. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 41, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.O. A Study on Sustainable Usage Intention of Blockchain in the Big Data Era: Logistics and Supply Chain Management Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.-S. The Interaction Effect of Information Systems of Shipping and Logistics Firms and Managers’ Support for Blockchain Technology on Cooperation with Shippers for Sustainable Value Creation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Available online: https://fcsalud.ua.es/en/portal-de-investigacion/documentos/tools-for-the-bibliographic-research/guide-of-systematic-reviews-in-social-sciences.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Thorpe, R.; Jackson, P.R. Management Research. 2012. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=3VJdBAAAQBAJ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, M.; Meester, W.J.; Steiginga, S.; Ross, C.A. A Brief History of Scopus: The World’s Largest Abstract and Citation Database of Scientific Literature. In Research Analytics: Boosting University Productivity and Competitiveness Through Scientometrics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R. Writing for Academic Journals, 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2013; Available online: https://books.google.com.mx/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pfPfAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Murray,+R.+Writing+for+Academic+Journals,+3rd+ed.%3B+Open+University+Press:+Maidenhead,+UK,+2013.&ots=8Gy-qITHaI&sig=16MwKbtH3PV3y-IUHrRrNdz0REs&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Murray%2C%20R.%20Writing%20for%20Academic%20Journals%2C%203rd%20ed.%3B%20Open%20University%20Press%3A%20Maidenhead%2C%20UK%2C%202013.&f=false (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Grignon, J.; Steven, R.; Guitart, D.A.; Byrne, J.A. Publishing Not Perishing: How Research Students Transition from Novice to Knowledgeable Using Systematic Quantitative Literature Reviews. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Knowledge Management in Startups: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. A systematic review of supply chain knowledge management research: State of the art and research opportunities. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromovs, G.; Lammi, M. Blockchain and internet of thing require innovative approach to logistics education. Transp. Probl. 2017, 12, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausdal, A.H.; Czachorowski, K.V.; Solesvik, M.Z. Applying blockchain technology: Evidence from Norwegian companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.-Y.; Wang, X. Applications of blockchain technology to logistics management in integrated casinos and entertainment. Informatics 2018, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijan, E.; Aksentijević, S.; Ivanić, K.; Jardas, M. Blockchain technology implementation in logistics. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Chung, C.Y.; Seyha, T.; Young, J. Factors affecting organizations resistance to the adoption of blockchain technology in supply networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribernik, M.; Zero, K.; Kummer, S.; Herold, D.M. City logistics: Towards a blockchain decision framework for collaborative parcel deliveries in micro-hubs. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdeaho, O.; Hilmola, O.-P. Business models amid changes in regulation and environment: The case of Finland–Russia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, I.J.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Huang, S.; Vazquez-Brust, D. Evaluating the factors that influence blockchain adoption in the freight logistics industry. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 141, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullón Pérez, J.J.; Queiruga-Dios, A.; Gayoso Martínez, V.; Del Rey, Á.M. Traceability of ready to wear clothing through blockchain technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Kang, K.; Costa, F. A blockchain-based framework for green logistics in supply chains. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozanli, Ö.; Kongar, E.; Gupta, S.M. Evaluation of waste electronic product trade-in strategies in predictive twin disassembly systems in the era of blockchain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada, N.; Ethirajan, M.; Kumar, A.; Vimal, K.; Nadeem, S.P.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Jayakrishna, K. Blockchain technology for enhancing traceability and efficiency in automobile supply chain: A case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritua, B.; Wagener, C.; Wagener, N.; Adamczak, M. Blockchain solutions for international logistics networks along the new silk road between Europe and Asia. Logistics 2021, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarlienė, N.; Meleniakas, M. Claims solutions using a blockchain system in international logistics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekrar, A.; Ait El Cadi, A.; Raca, T.; Joseph, S. Digitalizing the closing-of-the-loop for supply chains: A transportation and blockchain perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, M.; Gogola, M.; Kubaľák, S.; Ondruš, J. Blockchain technology as a new driver in supply chain. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 55, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S.; Bader, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Trollman, H.; Fadiji, T.; Salonitis, K. Food logistics 4.0: Opportunities and challenges. Logistics 2021, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Ghani, R.F. A proposed hash algorithm to use for blockchain base transaction flow system. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2021, 9, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, Y.; Shin, Y. Data usage and the legal stability of transactions for the commercial operation of autonomous vessels based on digital ownership in Korean civil law. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novinkina, J.; Davydovitch, A.; Vasiljeva, T.; Haidabrus, B. Industries pioneering blockchain technology for electronic data interchange. Acta Logist. 2021, 8, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislawski, R.; Szymonik, A. Impact of Selected Intelligent Systems in Logistics on the Creation of a Sustainable Market Position of Manufacturing Companies in Poland in the Context of Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straubert, C.; Sucky, E. How Useful is a Distributed Ledger for Tracking and Tracing in Supply Chains? A Systems Thinking Approach. Logistics 2021, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, W. Visualizing Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Scientometric Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yeung, J.-K.-W.; Lau, Y.-Y.; So, J. Technical Sustainability of Cloud-Based Blockchain Integrated with Machine Learning for Supply Chain Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunmozhi, M.; Venkatesh, V.; Arisian, S.; Shi, Y.; Sreedharan, V.R. Application of Blockchain and Smart Contracts in Autonomous Vehicle Supply Chains: An Experimental Design. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 165, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, B.; Güner, E.; Son-Turan, S. Blockchain Technology and Sustainability in Supply Chains and a Closer Look at Different Industries: A Mixed Method Approach. Logistics 2022, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Luna, P.; García-Río, E. Tecnología Blockchain: Desafíos Presentes y Futuros en su Aplicación. Rev. Conhecimiento Online 2022, 2, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlan, V.; Sys, C.; Vanelslander, T. Cost-Effectiveness and Gain-Sharing Scenarios for Purchasing a Blockchain-Based Application in the Maritime Supply Chain. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L.; Guo, L.-H.; Zhou, M.; Tsaur, W.-J.; Sun, H.; Zhan, W.; Deng, Y.-Y.; Li, C.-T. Blockchain-Based Anti-Counterfeiting Management System for Traceable Luxury Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukleang, T.; Jandaeng, C. Security Enhancement in Smart Logistics with Blockchain Technology: A Home Delivery Use Case. Informatics 2022, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Narayanan, A.; Zhuang, J. Blockchain in Humanitarian Operations Management: A Review of Research and Practice. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 80, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.H. Enhancing Competitive Capabilities of Healthcare SCM through the Blockchain: Big Data Business Model’s Viewpoint. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztes, É.R.; Kovács, I.; Horváth, A.; Zimányi, K. Exploratory Analysis of Blockchain Platforms in Supply Chain Management. Economies 2022, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Parvaiz, G.S.; Ali, A.; Jehangir, M.; Hassan, N.; Bae, J. A Model for Understanding the Mediating Association of Transparency between Emerging Technologies and Humanitarian Logistics Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthimkhulu, A.; Jokonya, O. Exploring the Factors Affecting the Adoption of Blockchain Technology in the Supply Chain and Logistic Industry. J. Transp. Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 16, a750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A. Adoption of Blockchain Technology Facilitates a Competitive Edge for Logistic Service Providers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhi, A.R.; Muthuswamy, P. Influence of Blockchain Technology in Manufacturing Supply Chain and Logistics. Logistics 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, M.; Zanin, A. Logistics and Agri-Food: Digitization to Increase Competitive Advantage and Sustainability. Literature Review and the Case of Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, Y. Blockchain-Enabled Cross-Border E-Commerce Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabhan, B.; Obaidat, M.A. Privacy-Preserving Blockchain Framework for Supply Chain Management: Perceptive Craving Game Search Optimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfaqih, M.; Balfagih, Z.; Lytras, M.D.; Alfawaz, K.M.; Alshdadi, A.A.; Eesa, A. A blockchain-enabled IoT logistics system for efficient tracking and management of high-price shipments: A resilient, scalable and sustainable approach to smart cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiuchenko, V.; Krajčovič, M.; Biňasová, V.; Papánek, L. Prospects for using blockchain technology in transportation and supply chain management. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi Maniam, P.S.; Prentice, C.; Sassenberg, A.-M.; Soar, J. Identifying an optimal model for blockchain technology adoption in the agricultural sector. Logistics 2023, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, W.; Al-Ansari, T. GM-Ledger: Blockchain-based certificate authentication for international food trade. Foods 2023, 12, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, C.; Coll, A. The influence of technologies in increasing transparency in textile supply chains. Logistics 2023, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Tolba, A.; Liu, Z.; Wen, W. A reliable delivery logistics system based on the collaboration of UAVs and vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubag, M.; Bonifacio, J.; Tan, J.M.; Concepcion, R., II; Mababangloob, G.R.; Galang, J.G.; Maniquiz-Redillas, M. Diversified impacts of enabling a technology-intensified agricultural supply chain on the quality of life in hinterland communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niavis, H.; Zafeiropoulou, A.M. A blockchain-based architecture and smart contracts for an interoperable physical internet. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2022–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjooei, D.; Alimohammadlou, M.; Askarifar, K. Industry 4.0 research in the maritime industry: A bibliometric analysis. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2023, 22, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitalleri, A.; Kavasidis, I.; Cartelli, V.; Mineo, R.; Rundo, F.; Palazzo, S.; Spampinato, C.; Giordano, D. BioTrak: A blockchain-based platform for food chain logistics traceability. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.09601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardivo, A.; Sánchez Martín, C.C. A study of blockchain adoption in the rail sector. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Sharma, P.; Choi, T.-M.; Lim, A. Blockchain and third-party logistics for global supply chain operations: Stakeholders’ perspectives and decision roadmap. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 170, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Selvarajan, S.; Obaidat, M.; Arfeen, S.U.; Khadidos, A.O.; Khadidos, A.O.; Maha, A. From hype to reality: Unveiling the promises, challenges and opportunities of blockchain in supply chain systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. A literature review on the application of digital technology in achieving green supply chain management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, A.G.; De Felice, F.; Forcina, A.; Petrillo, A. Role and application of advanced digital technologies in achieving sustainability in multimodal logistics operation: A systematic literature review. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaštelan, N.; Vidan, P.; Assani, N.; Miličević, M. Digital Horizon: Assessing current status of digitalization in maritime industry. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.; Jaber, M.; Sharabati, A.-A.A.; Nasereddin, A.Y.; Marei, A. The blockchain effect on courier supply chains digitalization and its contribution to Industry 4.0 within the circular economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvubu, M.; Naude, M.J. Blockchain in the logistics sector: A systematic literature review of benefits and constraints. J. Transp. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 18, a1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, H.; Fan, J. Revolutionizing retail: Examining the influence of blockchain-enabled IoT capabilities on sustainable firm performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Velarde, D.V.; Salazar-Echeagaray, J.E.; Aya, F.A.; Cano-Vargas, Á.A. Logistics 4.0: Transformative potential and challenges in agribusiness. J. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 12, 45–58. Available online: https://systems.enpress-publisher.com/index.php/jipd/article/view/2871/2143 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Peng, H.; Sun, Y.; Hao, J.; An, C.; Lyu, L. Carbon emissions trading in ground transportation: Status quo, policy analysis, and outlook. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 131, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quliyev, V.M.; Abbasova, S.A.; Aliyeva, M.S.; Samedova, E.R.; Mammadova, M.A. Analysis of corporate management risks in the work of logistic enterprises. Acta Logist. 2024, 11, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theotokas, I.N.; Lagoudis, I.N.; Raftopoulou, K. Challenges of maritime human resource management for the transition to shipping digitalization. J. Shipp. Trade 2024, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, M.A.; Bookbinder, J.H.; Yun, N.Y. Leveraging Industry 4.0 technologies for sustainable humanitarian supply chains: Evidence from the extant literature. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialp, A.; Merigó, J.M.; Cancino, C.A.; Urbano, D. Twenty-five years (1992–2016) of the International Business Review: A bibliometric overview. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, K.W. The author cocitation structure of macroeconomics. Scientometrics 1983, 5, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M. Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. Am. Doc. 1963, 14, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyack, K.W.; Klavans, R. Co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, and direct citation: Which citation approach represents the research front most accurately? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 2389–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lee, J.-Y.; Gharehgozli, A. Blockchain implementation in the maritime industry: A literature review and synthesis analysis of benefits and challenges. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2024, 26, 630–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Chen, P.S.-L.; Du, Y. Risk assessment of maritime container shipping blockchain-integrated systems: An analysis of multi-event scenarios. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 163, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-S. Maritime shipping digitalization: Blockchain-based technology applications, future improvements and intention to use. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 131, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.W.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Yaqoob, I.; Omar, M. Blockchain in oil and gas industry: Applications, challenges, and future trends. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretti, J.W.; Mergulhão, R.C.; Mendes, J.V. Evolution of blockchain technology in sustainable supply chain management: A theoretical perspective. World Rev. Intermodal Transp. Res. 2023, 11, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punathumkandi, S.; Sundaram, V.M.; Paneer, P. Interoperable permissioned-blockchain with sustainable performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelakowski, A.S. Global container shipping market development and its impact on mega logistics system. Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2019, 13, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambourdiere, E.; Corbin, E. Blockchain and maritime supply-chain performance: Dynamic capabilities perspective. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Boakye, E.; Zhao, H.; Ahia, B.N.K. Blockchain technology prospects in transforming Ghana’s economy: A phenomenon-based approach. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2023, 29, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epps, T.; Carey, B.; Upperton, T. Revolutionizing global supply chains one block at a time: Growing international trade with blockchain: Are international rules up to the task? Glob. Trade Cust. J. 2019, 14, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugović, A.; Bukša, H.J.; Dragoslavić, A.; Sopta, D. The possibilities of applying blockchain technology in shipping. Pomorstvo 2019, 33, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Men, S.; Guo, T. Application of blockchain technology in value chain of procurement in manufacturing enterprises. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 1674412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Singh, H.; Chaturvedi, K.R.; Rakesh, S. Blockchain in logistics industry: In fizz customer trust or not. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Chen, P.S.-L.; Du, Y. Blockchain adoption in container shipping: An empirical study on barriers, approaches, and recommendations. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.-W.; Song, Z.-Y.; Lin, C.-W.; Lam, J.S.L.; Chen, J. New framework of port logistics in the post-COVID-19 period with 6th-generation ports (6GP) model. Transp. Rev. 2024, 45, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangsakul, M.; Sureeyatanapas, P. Understanding critical barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in the logistics context: An interpretive structural modelling approach. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amico, C.; Cigolini, R. Improving port supply chain through blockchain-based bills of lading: A quantitative approach and a case study. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2024, 26, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Lu, H.; Wang, H. Design and value analysis of the blockchain-based port logistics financial platform. Marit. Policy Manag. 2024, 51, 1037–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavassano, G.; Ferrari, C.; Tei, A. Blockchain: How shipping industry is dealing with the ultimate technological leap. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 34, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lai, P.-L.; Yang, C.-C. Determinants of blockchain adoption in the aviation industry: Empirical evidence from Korea. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Gerlitz, L.; Henesey, L. Cross-border capacity-building for port ecosystems in small and medium-sized baltic ports. TalTech J. Eur. Stud. 2021, 11, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F. Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquita, Y.; Podgorelec, B.; Gil-González, A.B.; Corchado, J.M. Blockchain-Based Supply Chain Systems, Interoperability Model in a Pharmaceutical Case Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Yue, X. Blockchain technology for port logistics capability: Exclusive or sharing. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021, 149, 347–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabrera, A.M.; García-Soto, M.G. Subnational institutional configurations and international expansion of SMEs in emerging economies. J. Int. Entrep. 2023, 21, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusher, A.; Dethlefsen, K.; Ledwoch, F.; Berretta, E. Cyber Security Risk Assessment in Autonomous Shipping. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ouyang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Ni, X.; Han, X.; Wang, F.-Y. Blockchain-Enabled Smart Contracts: Architecture, Applications, and Future Trends. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 2266–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lu, M.-F. Supply chain re-engineering using blockchain technology: A case of smart contract based tracking process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkol, M.; Selviaridis, K.; Finne, M. The governance of collaboration in complex projects. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cartagena, M.; Kim, S. Secure and Transparent Space Exploration Data Management Using a Hybrid Blockchain Model. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoade, G.; Karande, V.; Khan, L.; Hamlen, K. Decentralized IoT data management using blockchain and trusted execution environment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 6–9 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, Z.; Mathews, M. A proposal to harmonize BIM and IoT data silos using blockchain application. In Proceedings of the CITa BIM Gathering 2021, Virtual, 21–23 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Farah, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Mahmoud, H.; Shah, S.A.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Taramonli, S.; Bellekens, X.; Abozariba, R.; Idrissi, M.; Aneiba, A. A Survey on Blockchain Technology in the Maritime Industry: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 157, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heutger, M.; Kückelhaus, M. Blockchain in Logistics: Perspectives on the Upcoming Impact of Blockchain Technology and Use Cases for the Logistics Industry; DHL Customer Solutions & Innovation: Troisdorf, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.dhl.com/content/dam/dhl/global/core/documents/pdf/glo-core-blockchain-trend-report.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y. Blockchain in Maritime: Applications, Effects and Challenges. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1627544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Göçer, F. Digital supply chain: Literature review and a proposed framework for future research. Comput. Ind. 2018, 97, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Laskowski, M. Toward an ontology-driven blockchain design for supply-chain provenance. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2018, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Islam, M.A.; Hassan, R.; Kumar, A. Emerging Blockchain Adoption in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2023, 72, 1191–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, J.; Pace, G.J. Towards External Calls for Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.I.; Britt, D.W. Resistance to Change. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 30, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip-Bruin, X.; Marín-Tordera, E.; Ruíz, J.; Jukan, A.; Trakadas, P.; Cernivec, A.; Lioy, A.; López, D.; Santos, H.; Gonos, A.; et al. Cybersecurity in ICT supply chains: Key challenges and a relevant architecture. Sensors 2021, 21, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Maritime Scope | Evidence Base | Corpus (Reported) | Method Type | Primary Output | What This SLR Adds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shin et al. [40] | Maritime supply chain | Academic and practical evidence | 73 academic and 75 practical | SLR and conceptual framework (TOE) | Application domains and adoption factors; TOE framing | Incorporates VOSviewer bibliographic coupling and robustness checks; evidence map with quality tiering; stronger legal/regulatory (eBL/enforceability) operationalization; IBAF critical appraisal. |

| Liu et al. [41] | Maritime supply chains | Literature synthesis | — | Review/synthesis (architecture-oriented) | Applications, architecture, challenges; proposed system architecture | Refocuses the focus on adoption/governance/institutional feasibility between maritime logistics actors; theory-coded synthesis (TOE/Institutional/RBV). |

| Guan and Shibasaki [42] | Port industry | Scopus and Web of Science (reported) | 316 articles | SLR | Port-focused adoption and sustainability insights | Expands from port-only to a maritime logistics ecosystem (ports–carriers–customs–docs); introduces evidence map and cluster structure and adoption framework (IBAF). |

| Nasser et al. [43] | MSW/PCS | Bibliometric and SLR | — | Bibliometric analysis and SLR | Trend mapping and agenda for MSW/PCS | Extends from MSW/PCS fragmentation to broader maritime logistics issues of adoption barriers (interoperability, eBL legality, and governance) and maps the field through bibliographic coupling. |

| Tsiulin et al. [44] | Shipping and port management | Literature review | — | Narrative review | Conceptual framing of blockchain in shipping/ports | Added with PRISMA-based SLR and explicit inclusion/exclusion; added bibliometric coupling for evidence/quality and map and theory-driven synthesis. |

| This study | Maritime logistics (ports–carriers–customs–trade docs) | Scopus; 2017–Sep 2024 | 78 journal articles | PRISMA 2020 SLR and descriptive and bibliographic coupling | 7 research priorities/clusters and IBAF | — |

| Keywords Used | |

|---|---|

| Date range | Published from 2017 to present |

| Scopus database | 944 |

| Social science area | 166 |

| Articles document type | 99 |

| Papers based on items of interest | 78 |

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| First criterion: Title and Abstract | Included those that were explicitly stated in the title/abstract to be (i) a primary theme of blockchain and, likewise, (ii) applicable to logistics/supply chain as well as maritime/shipping domains. Studies where the blockchain was secondary such as an Industry 4.0 generic or without logistics/maritime fit did not meet our criteria and were removed from the records. |

| Second criterion: Focus of the papers | “Utilized during full-text reading with a screening codebook. A paper was included when blockchain featured as an analytical object (explicitly mentioned in aim or research question) and was investigated considering logistics/maritime processes (e.g., ports, carriers, customs, documentation/eBL). Papers that mentioned blockchain on the perimeter (briefly noted as peripheral without analysis) “would be eliminated”. |

| Study | Maritime-Specific (Y/N) | Study Type | Unit of Analysis | Theory Used | Data Type | Key Barrier(s) Coded | Quality Tier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gromovs (2017) [61] | N | Conceptual | Education/Training | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Gausdal (2018) [62] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST; REG; RES | Low |

| Liao and Wang (2018) [63] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT; PRIV | Low |

| Litke (2019) [10] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Tijan et al. (2019) [64] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Choi et al. (2020) [65] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | RES | Low |

| Dutta et al. (2020) [8] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Hribernik et al. (2020) [66] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV | Low |

| Irannezhad (2020) [37] | Y | Design/Architecture | Port/PCS | Transaction cost | None/Conceptual | COST; SCAL | Low |

| Jović et al. (2020) [39] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST | Low |

| Lähdeaho and Hilmola (2020) [67] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | REG | Low |

| Orji et al. (2020) [68] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Park (2020) [48] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | TOE; UTAUT | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Bullón Pérez et al. (2020) [69] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Tan et al. (2020) [70] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Tozanli et al. (2020) [71] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Zhou et al. (2020) [35] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | CSF | None/Conceptual | RES | Medium |

| Ada et al. (2021) [72] | N | Case study | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Primary | — | Low |

| Argumedo-García et al. (2021) [34] | N | Bibliometric | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Aritua et al. (2021) [73] | N | Model/Framework | Customs/Trade | None stated | None/Conceptual | REG | Medium |

| Bae (2021) [49] | Y | Conceptual | Maritime SC (multi-actor) | RBV | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021) [38] | Y | Conceptual | Customs/Trade | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV; REG | Low |

| Batarlienė and Meleniakas (2021) [74] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | Game theory | None/Conceptual | COST; PRIV | Medium |

| Bekrar et al. (2021) [75] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Moritz et al. (2021) [32] | N | SLR/Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Berneis and Winkler (2021) [33] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Černý et al. (2021) [76] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT; PRIV | Low |

| Jagtap et al. (2021) [77] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST | Low |

| Ali and Ghani (2021) [78] | N | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Lee et al. (2021) [79] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | REG | Low |

| Novinkina et al. (2021) [80] | N | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Pu and Lam (2021) [36] | Y | Model/Framework | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV; PRIV | Low |

| Rejeb et al. (2021) [31] | N | Bibliometric | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | RES | Low |

| Stanislawski and Szymonik (2021) [81] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Straubert and Sucky (2021) [82] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Su et al. (2021) [83] | N | SLR/Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Teodorescu and Korchagina (2021) [12] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Wong et al. (2021) [84] | Y | Design/Architecture | Maritime SC (multi-actor) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Arunmozhi et al. (2022) [85] | N | Design/Architecture | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST | Low |

| Ayan et al. (2022) [86] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Baena-Luna and García-Río (2022) [87] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Carlan et al. (2022) [88] | Y | Conceptual | Maritime SC (multi-actor) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST | Low |

| Chen et al. (2022) [89] | N | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Chukleang and Jandaeng (2022) [90] | N | Design/Architecture | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV; SCAL | Medium |

| Hunt et al. (2022) [91] | N | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV | Low |

| Jung (2022) [92] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT; SCAL | Low |

| Keresztes et al. (2022) [93] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST; INT | Low |

| Khan et al. (2022) [94] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Mthimkhulu and Jokonya (2022) [95] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | TOE | None/Conceptual | COST; PRIV; REG | Low |

| Noor (2022) [96] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV; SCAL | Low |

| Santhi and Muthuswamy (2022) [97] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Remondino and Zanin (2022) [98] | N | Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Zhou and Liu (2022) [99] | N | SLR/Review | Customs/Trade | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Aljabhan and Obaidat (2023) [100] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Balfaqih et al. (2023) [101] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Bastiuchenko et al. (2023) [102] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Gandhi Maniam et al. (2023) [103] | N | Model/Framework | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| George and Al-Ansari (2023) [104] | Y | Conceptual | Maritime SC (multi-actor) | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV; PRIV | Low |

| Hauschild and Coll (2023) [105] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Li et al. (2023) [106] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST; GOV; PRIV | Low |

| Lubag et al. (2023) [107] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV; PRIV | Low |

| Niavis and Zafeiropoulou (2023) [108] | N | Design/Architecture | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | COST; GOV; INT | Low |

| Razmjooei et al. (2023) [109] | Y | Bibliometric | General/Conceptual | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Spitalleri et al. (2023) [110] | N | Model/Framework | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Tardivo and Sánchez Martín (2023) [111] | N | Conceptual | Customs/Trade | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT | Low |

| Tiwari et al. (2023) [112] | N | Conceptual | 3PL/Forwarder | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV; PRIV | Low |

| Uddin et al. (2023) [113] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Wang et al. (2023) [114] | N | Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Fareed et al. (2024) [115] | N | SLR/Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Kaštelan et al. (2024) [116] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV | Low |

| Masa’deh et al. (2024) [117] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Mvubu and Naude (2024) [118] | N | SLR/Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | GOV | Low |

| Nazir and Fan (2024) [119] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | INT; SCAL | Low |

| Osuna-Velarde et al. (2024) [120] | N | SLR/Review | Supply chain (general) | None stated | Secondary | — | Low |

| Peng et al. (2024) [121] | N | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | — | Low |

| Quliyev et al. (2024) [122] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | PRIV | Low |

| Theotokas et al. (2024) [123] | Y | Conceptual | General/Conceptual | None stated | None/Conceptual | RES | Low |

| Ülkü et al. (2024) [124] | N | Conceptual | Supply chain (general) | None stated | None/Conceptual | GOV | Low |

| Authors | Topics | Key Insights Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021); Grzelakowski (2019); Tiwari et al. (2023) [38,112,135] | Increased Visibility | Blockchain provides an open distributed ledger that offers end-to-end transparency of shipment and can prevent fraudulent activities while enhancing responsibility within the supply chain. |

| George and Al-Ansari (2023); Irannezhad (2020); Lambourdiere and Corbin (2020) [37,104,136] | Simplified Documentation | Blockchain technology digitizes critical documents, such as Bills of Lading, helping to minimize delays, errors, and fraudulent activities associated with traditional paper-based systems. |

| Asante Boakye et al. (2022); Epps et al. (2019); George and Al-Ansari (2023); Lambourdiere and Corbin (2020) [104,136,137,138] | Automated Smart Contracts | Smart contracts in blockchain automatically execute predefined actions such as processing payments and updating shipment statuses, which eliminates intermediaries and accelerates operations. |

| Ada et al. (2021); Jugović et al. (2019); Wang et al. (2021); Yang (2019) [72,131,139,140] | Operational Efficiency | By automating manual tasks and reducing human involvement, blockchain enhances workflow efficiency, reducing errors, and speeding up processes across the supply chain. |

| Jain et al. (2020); Nguyen et al. (2023); Teodorescu and Korchagina (2021) [12,141,142] | Continuous Shipment Monitoring | Blockchain and IoT real-time tracking of goods helps companies to provide their stakeholders with information regarding the location, condition, and situation of the shipment. |

| Lee et al. (2024); Tangsakul and Sureeyatanapas (2024) [143,144] | Cost Savings | The application of blockchain substantially reduces transaction costs by eliminating intermediaries and interferences, souping-up processes, and reducing mistakes, all of which lead to an increase in cost. |

| Ayan et al. (2022); Cheung et al. (2021); Dutta et al. (2020); Yang (2019) [2,8,86,131] | Enhanced Data Security | Blockchain’s decentralized structure strengthens the security of sensitive logistics and financial data, reducing vulnerabilities to cyberattacks and unauthorized data alterations. |

| Amico and Cigolini (2024); Lu et al. (2024); Tönnissen and Teuteberg (2020) [4,145,146] | Fraud Prevention | The immutability character of blockchain would help to minimize the likelihood of fraudulent activities in the maritime supply chain by not allowing others to change the shipment information. |

| Bavassano et al. (2020); Li et al. (2021); Meyer et al. (2021) [147,148,149] | Support for Standardization | Blockchain enables secure sharing of data and makes it easier for everyone to sing from the same hymn sheet across the global supply chain, while all agree to play it one way and collaborate. |

| Adoption Factor | TOE Bucket | Institutional Interpretation | RBV Interpretation | Representative Evidence in the Reviewed Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compatibility with old systems; data standards | Technological | Normative pressure for standard and common; consortia coordination | Integration capability; IT architecture competence | Irannezhad (2020); Zhou et al. (2020); Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021); Jović et al. (2020); Digital Container Shipping Association (2025) [7,35,37,38,39] |

| Cybersecurity risk; privacy; smart-contract vulnerabilities | Technological | Compliance demand; uncertainty in liability risk | Security capability; risk-management routines | Tusher et al. (2022); Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021) [38,154] |

| Scalability/performance and implementation complexity | Technological | Mimetic reluctance if there are few demonstrable large-scale deployments | Execution capability; vendor/partner management | Irannezhad (2020); Zhou et al. (2020) [35,37] |

| High implementation cost; unclear ROI | Organizational | Uncertain market; not enough clarity of institutions | Financial slack; investment governance capability | Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021); Park (2020) [38,48] |

| Resistance to change; limited skills | Organizational | Professional norms; path dependence in port–carrier routines | Human capital; change-management capability | Park (2020); Irannezhad (2020) [37,48] |

| Multi-stakeholder governance (ports–carriers–customs); network effects | Environmental | Gatekeeping, coercive isomorphism; coordination as institutional work | Relational capability; ecosystem orchestration | Pu and Lam (2021); Zhou et al. (2020); Balci and Surucu-Balci (2021) [35,36,38] |

| Legal recognition of eBL/transferable records | Environmental | Formal institutional isomorphic demands for capture of documentation value | Capability to redesign documentation processes | UNCITRAL (2017); UK Parliament (2023) [5,6] |

| Partner pressure and ecosystem standards (ports, customs, shipping alliances) | Environmental | Coercive and normative isomorphism; mimetic adoption in the face of uncertainty | Social inputs; reputation and trust capital | Zhou et al. (2020); Pu and Lam (2021) [35,36] |

| No. | Research Area | Description | Potential Research Questions | Suggested Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technological Interoperability | Assess the integration of blockchain with other technologies (IoT, AI, big data) to optimize maritime logistics processes. | How can interoperability between blockchain and other technologies enhance efficiency in maritime port logistics? - What are the main technical barriers to integrating blockchain into existing systems? | Case studies, computational simulations, expert interviews in logistics technology. |

| 2 | Economic and Operational Impact | Analyze the benefits and costs of implementing blockchain in maritime logistics operations. | - What are the tangible and intangible economic benefits of adopting blockchain in maritime logistics? - How does blockchain impact transaction costs in maritime supply chains? | Econometric modeling, ROI (Return on Investment) analysis, longitudinal studies. |

| 3 | Cybersecurity and Privacy | Explore how blockchain can address challenges related to data security and privacy in maritime operations. | - What specific vulnerabilities can blockchain mitigate in maritime logistics? - How can blockchain ensure data privacy among multiple stakeholders in maritime supply chains? | Vulnerability analysis, regulatory review, threat modeling. |

| 4 | Adoption and Scalability | Studying the organizational, cultural, and regulatory barriers to the widespread adoption of blockchain in the maritime industry. | - What are the key factors influencing blockchain adoption by global maritime stakeholders? - What business models can facilitate faster blockchain adoption? | Surveys of logistics actors, qualitative analysis, interviews with executives. |

| 5 | Environmental Sustainability | Examine the potential of blockchain to promote eco-friendly practices in maritime logistics, such as reducing emissions and waste. | - How can blockchain optimize maritime routes to minimize environmental impact? - What role does blockchain play in real-time emissions monitoring? | Geospatial analysis, simulation studies, review of global best practices. |

| 6 | Standardization of Protocols | Investigate how to develop global standards for blockchain use in the maritime industry. | - What frameworks can facilitate blockchain standardization in global maritime trade? - How can international organizations collaborate to establish global standards? | Regulatory analysis, comparison of global case studies, development of theoretical frameworks. |

| 7 | Impact on Decision-Making | Analyze how blockchain affects transparency and trust among stakeholders in the maritime supply chain. | - How does blockchain influence collaborative decision-making in maritime trade? - What benefits does blockchain-driven transparency bring to small-scale actors in the sector? | Case studies, stakeholder surveys, data network analysis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Sánchez, C.; Menéndez-García, J.; Silva, J.A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Monroy-Becerril, D.M.; Hakizimana, E. Blockchain Technology and Maritime Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2026, 10, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010012

Muñoz-Sánchez C, Menéndez-García J, Silva JA, Garza-Reyes JA, Monroy-Becerril DM, Hakizimana E. Blockchain Technology and Maritime Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics. 2026; 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Sánchez, Christian, Jesica Menéndez-García, Jorge Alejandro Silva, Jose Arturo Garza-Reyes, Dulce María Monroy-Becerril, and Eugene Hakizimana. 2026. "Blockchain Technology and Maritime Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review" Logistics 10, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010012

APA StyleMuñoz-Sánchez, C., Menéndez-García, J., Silva, J. A., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Monroy-Becerril, D. M., & Hakizimana, E. (2026). Blockchain Technology and Maritime Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics, 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010012