Cognitive Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in Pharmaceuticals: The Mediating Roles of Forecasting, Synchronization, and Transparency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cognitive Supply Chain Management (CSCM)

2.2. Supply Chain Forecasting (SCF)

2.3. Supply Chain Synchronization (SCS)

2.4. Supply Chain Transparency (SCT)

2.5. Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM)

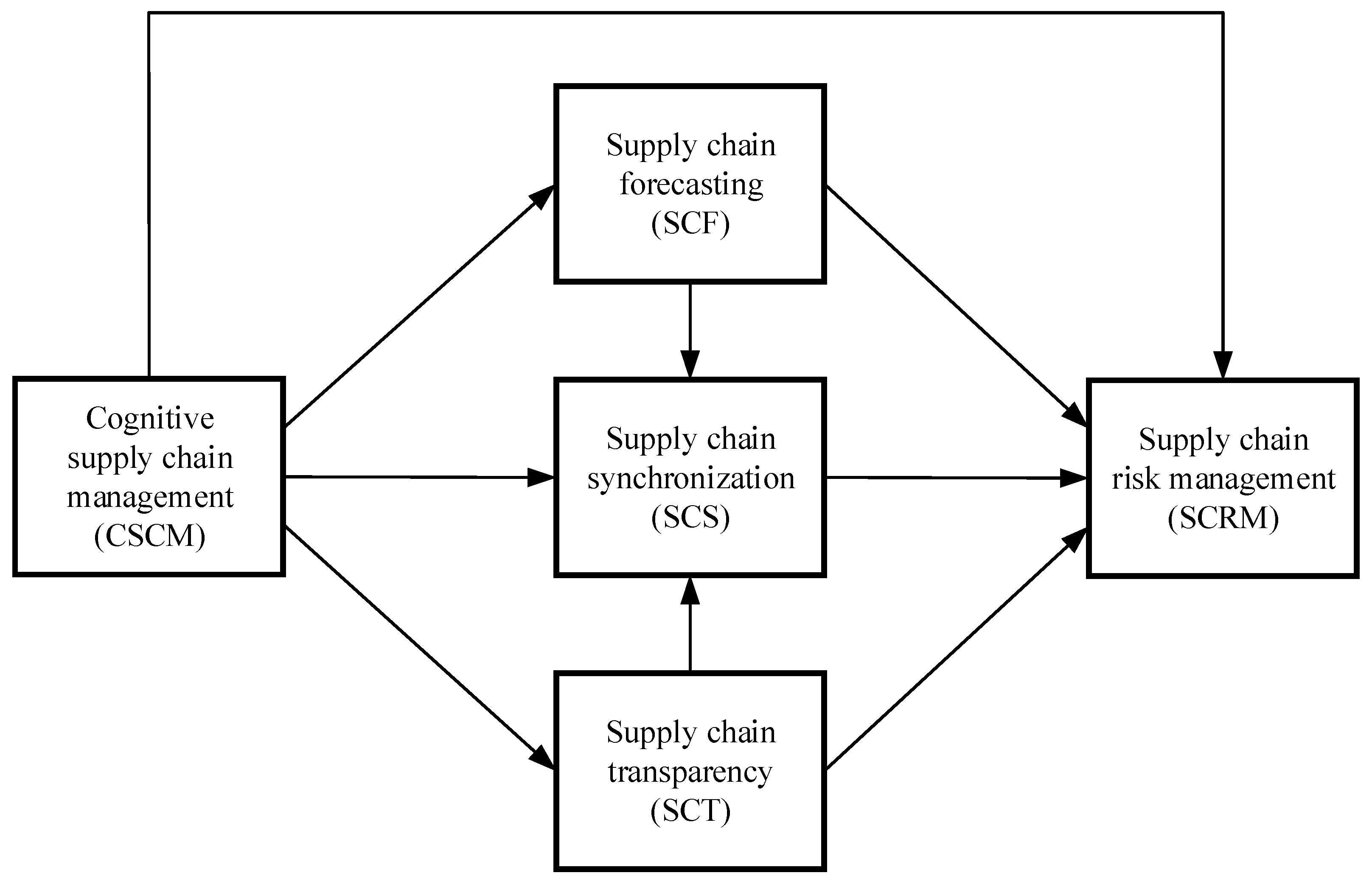

3. Hypotheses Development and Conceptual Framework

3.1. The Impact of CSCM on SCRM

3.2. The Impact of CSCM on SCF, SCS, and SCT

3.3. The Impact of SCF, SCS, and SCT on SCRM

3.4. The Impact of SCF and SCT on SCS

3.5. SCF, SCS, and SCT as Mediators

3.6. Conceptual Framework

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Survey and Measurement Items

4.2. Sampling and Data Collection

4.3. Control for Survey Bias

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

5.2. Structural Model Assessment

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Findings

7.2. Theoretical Implications

7.3. Practical Implications

7.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, Y.; Stevenson, M. A review of supply chain risk management: Definition, theory, and research agenda. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Al-Okaily, M.; Tanveer, M.I. Revolutionizing supply chain management: A critical meta-analysis of empowerment and constraint factors in blockchain technology adoption. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 30, 1472–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Żywiołek, J.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Shahzad, U.; Zhao, X.; Saikouk, T. Enhancing cognitive metrics in supply chain management through information and knowledge exchange. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2025, 36, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yu, H.; Wu, H.; Chen, J. Impacts of cognitive and social distances on supply chain capability: The moderating effect of information technology utilization. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cihan, E.E. Navigating supply chain paradoxes: A cognitive framework for managerial strategy based on systematic literature synthesis. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2025, 36, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zighan, S.; Dwaikat, N.Y.; Alkalha, Z.; Abualqumboz, M. Knowledge management for supply chain resilience in pharmaceutical industry: Evidence from the Middle East region. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 1142–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Laghouag, A. The maturity of sustainable supply chain management practices: An applied study on pharmaceutical firms. J. Money Bus. 2023, 3, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaktoom, A.T.; Yusuf, N. Optimizing forecasting techniques for cost-effective procurement of controlled medications in Saudi Arabia’s healthcare system. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2025, 19, 1186–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon-Jones, E.; Squire, B.; Autry, C.W.; Petersen, K.J. A contingent resource-based perspective of supply chain resilience and robustness. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Ngah, A.H.; Pradeepa Jayaratne, M.D.R.; Rahi, S.; Tunio, M.N. Role of information processing and digital supply chain in supply chain resilience through supply chain risk management. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2024, 17, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waage, F. Fully synchronized supply chain forecasting. In Advances in Business and Management Forecasting; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E.; Rutschmann, E. Big data analytics and demand forecasting in supply chains: A conceptual analysis. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 739–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, J.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. Nexus supplier transparency and supply network accessibility: Effects on buyer ESG risk exposure. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2025, 45, 895–924. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y. Improving supply chain resilience from the perspective of information processing theory. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 721–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtfeld, G.M.; Gruchmann, T. Dynamic capabilities for supply chain resilience: A meta-review. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 623–648. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.J.; Seuring, S.; Chen, L.; Azadegan, A. Guest editorial: Supply chain transparency: Opportunities, challenges and risks. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J. Designing Complex Organizations; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, A.; Ahsan, K.; Rahman, S. Application of artificial intelligence in demand planning for supply chains: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2025, 36, 672–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, M.M.; Ettkin, L.P.; Chapman, S. Supply chain forecasting–collaborative forecasting supports supply chain management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2000, 6, 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- Kambil, A. Synchronization: Moving beyond re-engineering. J. Bus. Strateg. 2008, 29, 51–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatupang, T.M.; Sridharan, R. An integrative framework for supply chain collaboration. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2005, 16, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Opoku Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.K.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Issau, K.; Ofori, D.; Faibil, D. Effect of information sharing in supply chains: Understanding the roles of supply chain visibility, agility, collaboration on supply chain performance. Benchmarking 2022, 29, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.R.; Gabler, C.B.; Manhart, P.S. Supply chain transparency: Theoretical perspectives for future research. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 1422–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Bryde, D.J.; Blome, C.; Roubaud, D.; Giannakis, M. Facilitating artificial intelligence powered supply chain analytics through alliance management during the pandemic crises in the B2B context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 96, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, R.; Schoenherr, T. Assessing and managing risks using the supply chain risk management process (SCRMP). Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 16, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicchia, C.; Strozzi, F. Supply chain risk management: A new methodology for a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Zhao, L. Reduce supply chain financing risks through supply chain integration: Dual approaches of alleviating information asymmetry and mitigating supply chain risks. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 1533–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghar, A.; Alinaghian, L.; Turner, N. The role of cognitive capital in supply chain resilience: An investigation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 28, 576–597. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.; Zheng, M.; Shen, Y. The effect of relational embeddedness on transparency in supply chain networks: The moderating role of digitalization. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 1621–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, T.; Kumar, M.; Sanders, N.; Sodhi, M.S.; Thürer, M.; Tortorella, G.L. From supply chain risk to system-wide disruptions: Research opportunities in forecasting, risk management and product design. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 1841–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Singh, N.P. Predicting supply chain risks through big data analytics: Role of risk alert tool in mitigating business disruption. Benchmarking 2023, 30, 1457–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S. Big data and big disaster: A mechanism of supply chain risk management in global logistics industry. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 274–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushaikha, I.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Yaseen, M.H.; Hamadneh, S.; Darwish, T.K. Leveraging animal feed supply chain capabilities through big data analytics: A qualitative study. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2025, 42, 2605–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Krikke, H.; Caniëls, M.C. Integrated supply chain risk management: A systematic review. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1123–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Boer, H.; Taran, Y. Supply chain integration, risk management and manufacturing flexibility. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 690–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.J.; Islam, N.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wang, H.; Au, K.M.A. How does supply chain transparency influence idiosyncratic risk in newly public firms: The moderating role of firm digitalization. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 1649–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Nazrul, A.; Yan, F. Supply chain transparency: A roadmap for future research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2024, 124, 2665–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, J. Examining the impact of leader’s paradoxical cognition on supply chain sustainability: A moderated chain mediation model. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 1760–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S. The performance effects of big data analytics and supply chain ambidexterity: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 222, 107498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. Blockchain’s roles in meeting key supply chain management objectives. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töyli, H.L.; Ojala, J.L.; Wieland, A.; Wallenburg, C.M. The influence of relational competencies on supply chain resilience: A relational view. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, Z.; Boylan, J.E.; Kolassa, S.; Nikolopoulos, K. Supply chain forecasting: Theory, practice, their gap and the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.; Oke, A. Antecedents of supply chain visibility in retail supply chains: A resource-based theory perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1217–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Monge, C.A.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Perego, A.; Sianesi, A.; Tumino, A. Measuring visibility to improve supply chain performance: A quantitative approach. Benchmarking 2010, 17, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.W.; Tan, G.W.H.; Lee, V.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Sohal, A. Unearthing the determinants of Blockchain adoption in supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2100–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fildes, R.; Goodwin, P.; Lawrence, M.; Nikolopoulos, K. Effective forecasting and judgmental adjustments: An empirical evaluation and strategies for improvement in supply-chain planning. Int. J. Forecast. 2009, 25, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, J.; Holweg, M.; Lawson, B.; Pil, F.K.; Wagner, S.M. The digitalization of operations and supply chain management: Theoretical and methodological implications. J. Oper. Manag. 2019, 65, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwaliez, O.M. The triple impact of green supply chain management on circular economy, environmental, and export performances. Benchmarking 2025, 32, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Weijters, B. Commentary on “common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies”. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbikat, N.; Bwaliez, O.M. Enhancing Kendall’s W using genetic algorithm: A computational approach to inter-rater reliability optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 278, 12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khatib, A.W. The impact of supply chain transparency and supply chain resilience on supply chain risk management: A moderation effect modeling. Supply Chain Manag. 2025, 30, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herburger, M.; Wieland, A.; Hochstrasser, C. Building supply chain resilience to cyber risks: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 29, 5–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Code | Item Description and Sources |

|---|---|

| Cognitive supply chain management [25,40] | |

| CSCM1 | “Our company uses AI/ML algorithms to analyze supply chain data in real time” |

| CSCM2 | “We employ predictive analytics to automate decision-making in supply chain operations” |

| CSCM3 | “IoT-enabled sensors are used to monitor inventory levels and shipment conditions” |

| CSCM4 | “We utilize blockchain technology to improve data security and traceability” |

| CSCM5 | “Our supply chain systems integrate cognitive computing (such as NLP, computer vision) for problem-solving” |

| Supply chain forecasting [43,48] | |

| SCF1 | “We use AI-driven tools to predict demand fluctuations with high accuracy” |

| SCF2 | “Our forecasts incorporate real-time market data (social trends, economic indicators)” |

| SCF3 | “We employ collaborative forecasting with suppliers and customers” |

| SCF4 | “Our forecasting models are regularly updated to reflect new data patterns” |

| SCF5 | “Forecast accuracy is measured and improved through feedback loops” |

| Supply chain synchronization [44,49] | |

| SCS1 | “Our supply chain partners share real-time data on inventory and orders” |

| SCS2 | “Production and logistics schedules are dynamically adjusted based on partner inputs” |

| SCS3 | “We use digital platforms (cloud ERP) to align planning across the supply chain” |

| SCS4 | “Our company and suppliers jointly optimize inventory levels to reduce bullwhip effects” |

| SCS5 | “We synchronize lead times with partners to minimize delays” |

| Supply chain transparency [41,45] | |

| SCT1 | “We have end-to-end visibility into Tier-1 and Tier-2 supplier activities” |

| SCT2 | “Our company tracks and discloses sustainability metrics (carbon footprint, labor practices)” |

| SCT3 | “We use blockchain/distributed ledger technology (DLT) to provide immutable records of product origins” |

| SCT4 | “Customers can access real-time information about product journey (design-to-delivery, farm-to-fork)” |

| SCT5 | “We audit and report supplier compliance with ethical standards” |

| Supply chain risk management [9,42] | |

| SCRM1 | “We maintain contingency plans for key supply chain disruptions (alternate suppliers)” |

| SCRM2 | “Our company regularly assesses risks (geopolitical, demand volatility) in the supply chain” |

| SCRM3 | “We use scenario planning to prepare for potential disruptions” |

| SCRM4 | “Our supply chain team collaborates with partners to mitigate joint risks” |

| SCRM5 | “We measure and track key risk indicators (KRIs) to monitor supply chain vulnerabilities” |

| Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 198 | 68.99 |

| Female | 89 | 31.01 |

| Total | 287 | 100 |

| Job position | ||

| Top management level | 105 | 36.59 |

| Middle management level | 139 | 48.43 |

| Low management level | 43 | 14.98 |

| Total | 287 | 100 |

| Job experience | ||

| Less than 5 years | 28 | 9.76 |

| 5—less than 10 years | 56 | 19.51 |

| 10—less than 15 years | 43 | 14.98 |

| 15—less than 20 years | 96 | 33.45 |

| 20 years and above | 64 | 22.30 |

| Total | 287 | 100 |

| Company size | ||

| Small (1—less than 100 employees) | 81 | 28.22 |

| Medium (100—less than 250 employees) | 143 | 49.83 |

| Large (250 employees and above) | 63 | 21.95 |

| Total | 287 | 100 |

| Item Code | VIF | Factor Loading | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive supply chain management | 0.600 | 0.834 | 0.842 | ||

| CSCM1 | 1.658 | 0.794 | |||

| CSCM2 | 1.661 | 0.760 | |||

| CSCM3 | 1.936 | 0.812 | |||

| CSCM4 | 1.733 | 0.749 | |||

| CSCM5 | 1.601 | 0.756 | |||

| Supply chain forecasting | 0.579 | 0.817 | 0.829 | ||

| SCF1 | 1.373 | 0.878 | |||

| SCF2 | 1.883 | 0.796 | |||

| SCF3 | 1.890 | 0.789 | |||

| SCF4 | 2.104 | 0.844 | |||

| SCF5 | 1.547 | 0.882 | |||

| Supply chain synchronization | 0.558 | 0.798 | 0.811 | ||

| SCS1 | 1.311 | 0.828 | |||

| SCS2 | 2.095 | 0.801 | |||

| SCS3 | 2.357 | 0.857 | |||

| SCS4 | 1.844 | 0.784 | |||

| SCS5 | 1.232 | 0.737 | |||

| Supply chain transparency | 0.518 | 0.752 | 0.833 | ||

| SCT1 | 2.069 | 0.810 | |||

| SCT2 | 2.309 | 0.847 | |||

| SCT3 | 1.763 | 0.830 | |||

| SCT4 | 1.386 | 0.743 | |||

| SCT5 | 1.168 | 0.841 | |||

| Supply chain risk management | 0.663 | 0.870 | 0.876 | ||

| SCRM1 | 2.587 | 0.844 | |||

| SCRM2 | 2.607 | 0.837 | |||

| SCRM3 | 2.668 | 0.869 | |||

| SCRM4 | 2.305 | 0.833 | |||

| SCRM5 | 1.535 | 0.772 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSCM | 0.775 | ||||

| 2. SCF | 0.687 | 0.761 | |||

| 3. SCS | 0.495 | 0.432 | 0.747 | ||

| 4. SCT | 0.347 | 0.373 | 0.251 | 0.720 | |

| 5. SCRM | 0.418 | 0.582 | 0.296 | 0.514 | 0.814 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSCM | - | ||||

| 2. SCF | 0.803 | - | |||

| 3. SCS | 0.586 | 0.514 | - | ||

| 4. SCT | 0.407 | 0.445 | 0.333 | - | |

| 5. SCRM | 0.482 | 0.682 | 0.354 | 0.632 | - |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CSCM → SCRM | −0.035 | 0.376 | 0.707 | Not supported |

| H2 | CSCM → SCF | 0.687 | 13.844 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | CSCM → SCS | 0.363 | 3.045 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H4 | CSCM → SCT | 0.347 | 3.308 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | SCF → SCRM | 0.467 | 3.955 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | SCS → SCRM | 0.025 | 0.267 | 0.790 | Not supported |

| H7 | SCT → SCRM | 0.346 | 4.559 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H8 | SCF → SCS | 0.158 | 1.079 | 0.281 | Not supported |

| H9 | SCT → SCS | 0.066 | 0.599 | 0.549 | Not supported |

| H10 | CSCM → SCF → SCRM | 0.321 | 3.794 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H11 | CSCM → SCS → SCRM | 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.905 | Not supported |

| H12 | CSCM → SCT → SCRM | 0.120 | 2.271 | 0.023 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abushaikha, I.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Bwaliez, O.M. Cognitive Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in Pharmaceuticals: The Mediating Roles of Forecasting, Synchronization, and Transparency. Logistics 2026, 10, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010011

Abushaikha I, Alqahtani MS, Bwaliez OM, Bwaliez OM. Cognitive Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in Pharmaceuticals: The Mediating Roles of Forecasting, Synchronization, and Transparency. Logistics. 2026; 10(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbushaikha, Ismail, Munirah Sarhan Alqahtani, Omar M. Bwaliez, and Ola M. Bwaliez. 2026. "Cognitive Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in Pharmaceuticals: The Mediating Roles of Forecasting, Synchronization, and Transparency" Logistics 10, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010011

APA StyleAbushaikha, I., Alqahtani, M. S., Bwaliez, O. M., & Bwaliez, O. M. (2026). Cognitive Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in Pharmaceuticals: The Mediating Roles of Forecasting, Synchronization, and Transparency. Logistics, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics10010011