Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacies of Cell-Free Supernatant of Dubosiella newyorkensis Against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Application in Food Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture

2.2. Preparation CFS from D. newyorkensis

2.3. Growth Curve

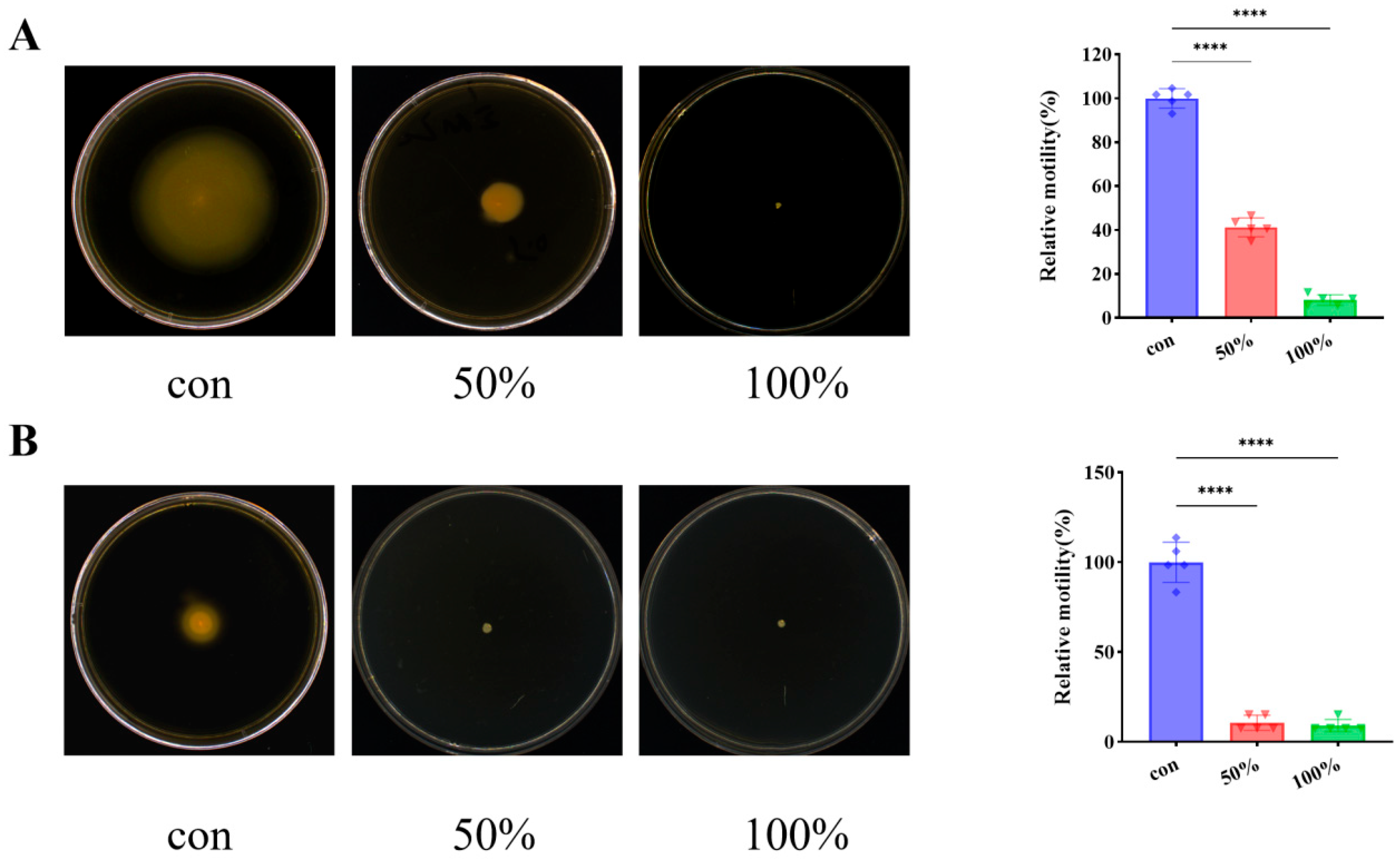

2.4. Motility Activity

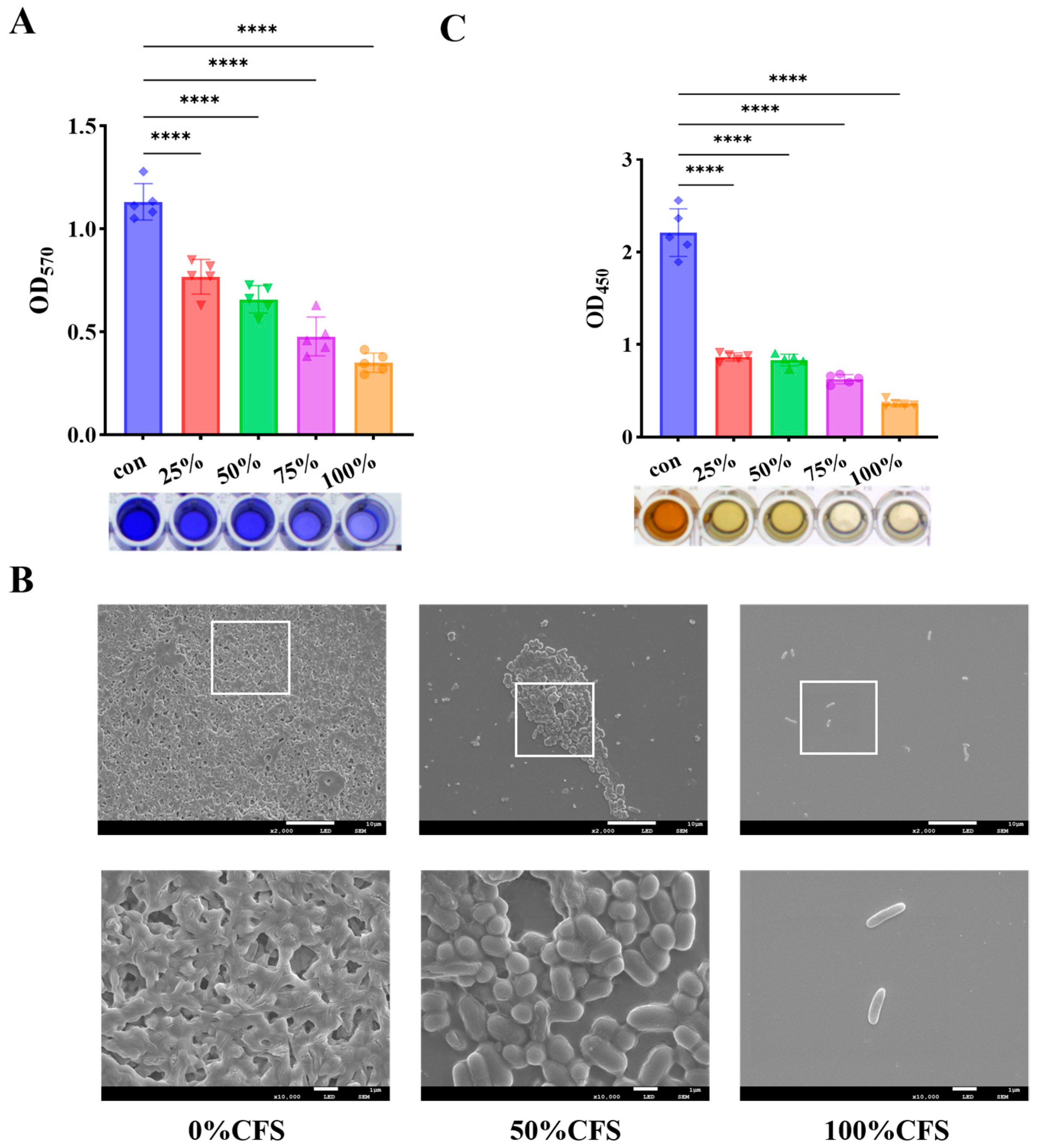

2.5. Biofilm Formation

2.6. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM)

2.7. Metabolic Activity

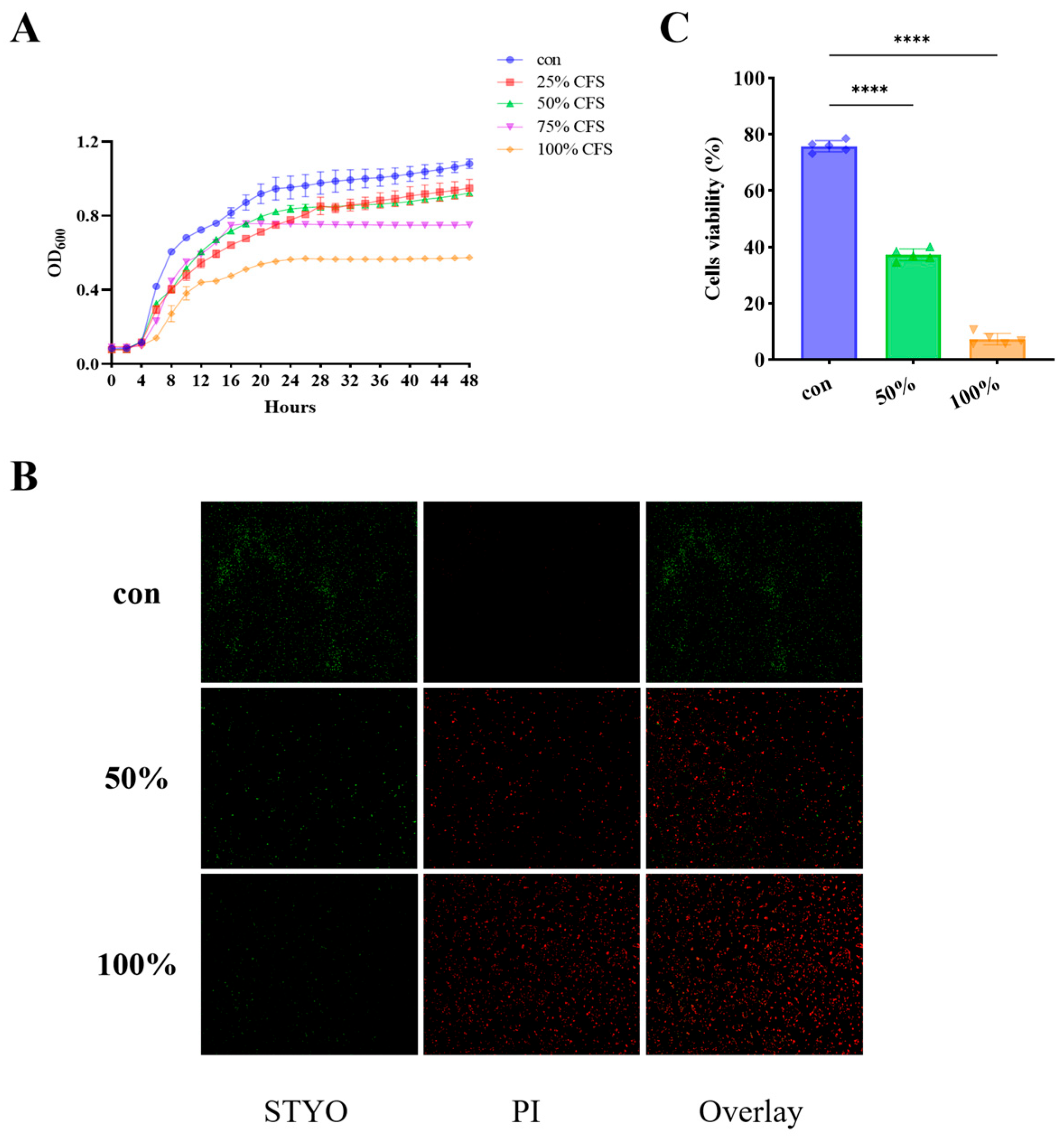

2.8. Live–Dead Cells Staining

2.9. Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) Assay

2.10. Gene Expression Analysis

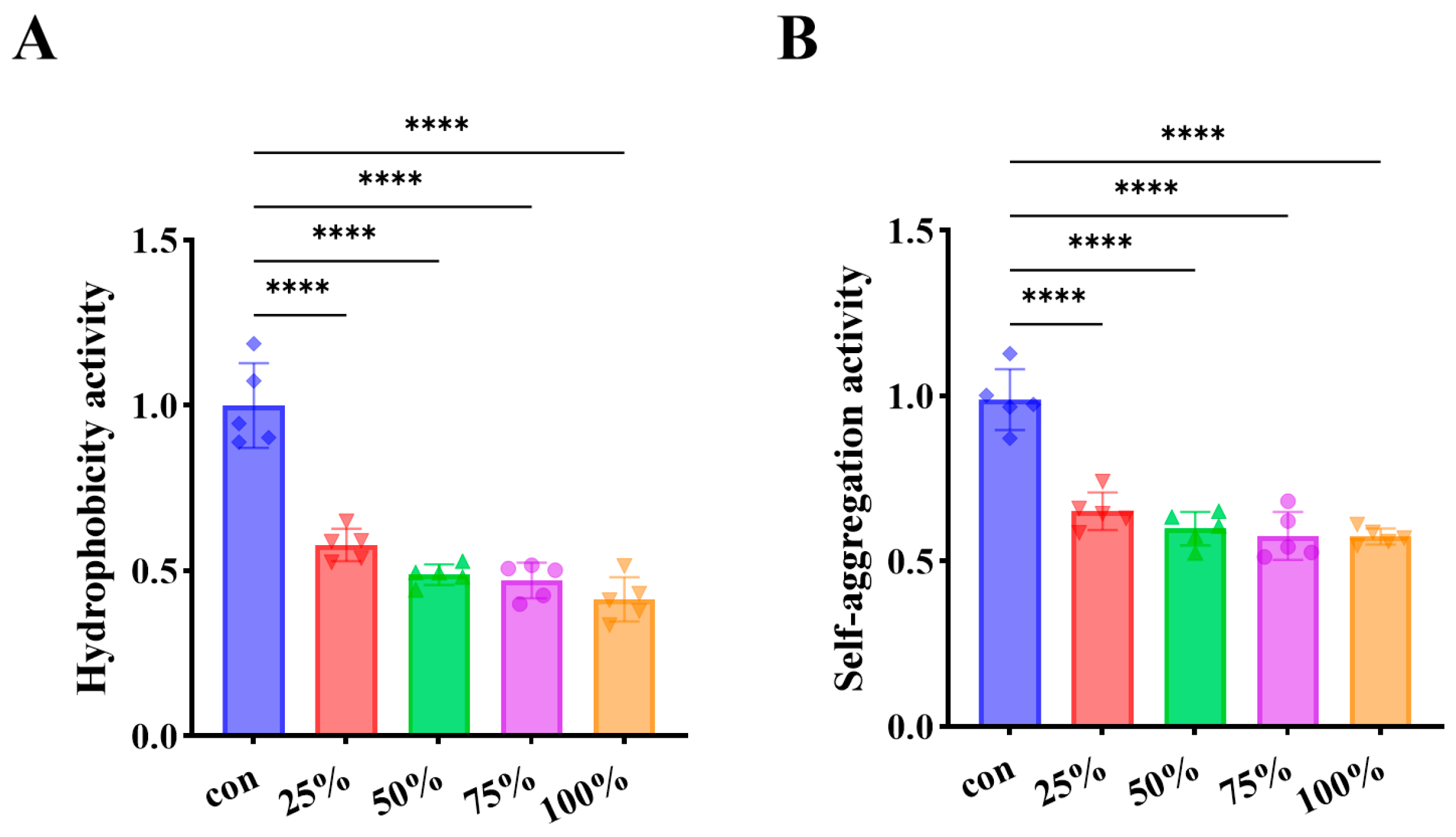

2.11. Determination of Self-Aggregating and Surface Hydrophobicity

2.12. Biofilm Formation on Content of Different Foods and Surfaces

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity of CFS In Vitro

3.2. CFS Reduced P. fluorescens Motility Ability

3.3. CFS Reduced Cell Surface Hydrophobicity and Self-Aggregation

3.4. CFS Suppressed Biofilm Development and Reduced Metabolic Activity

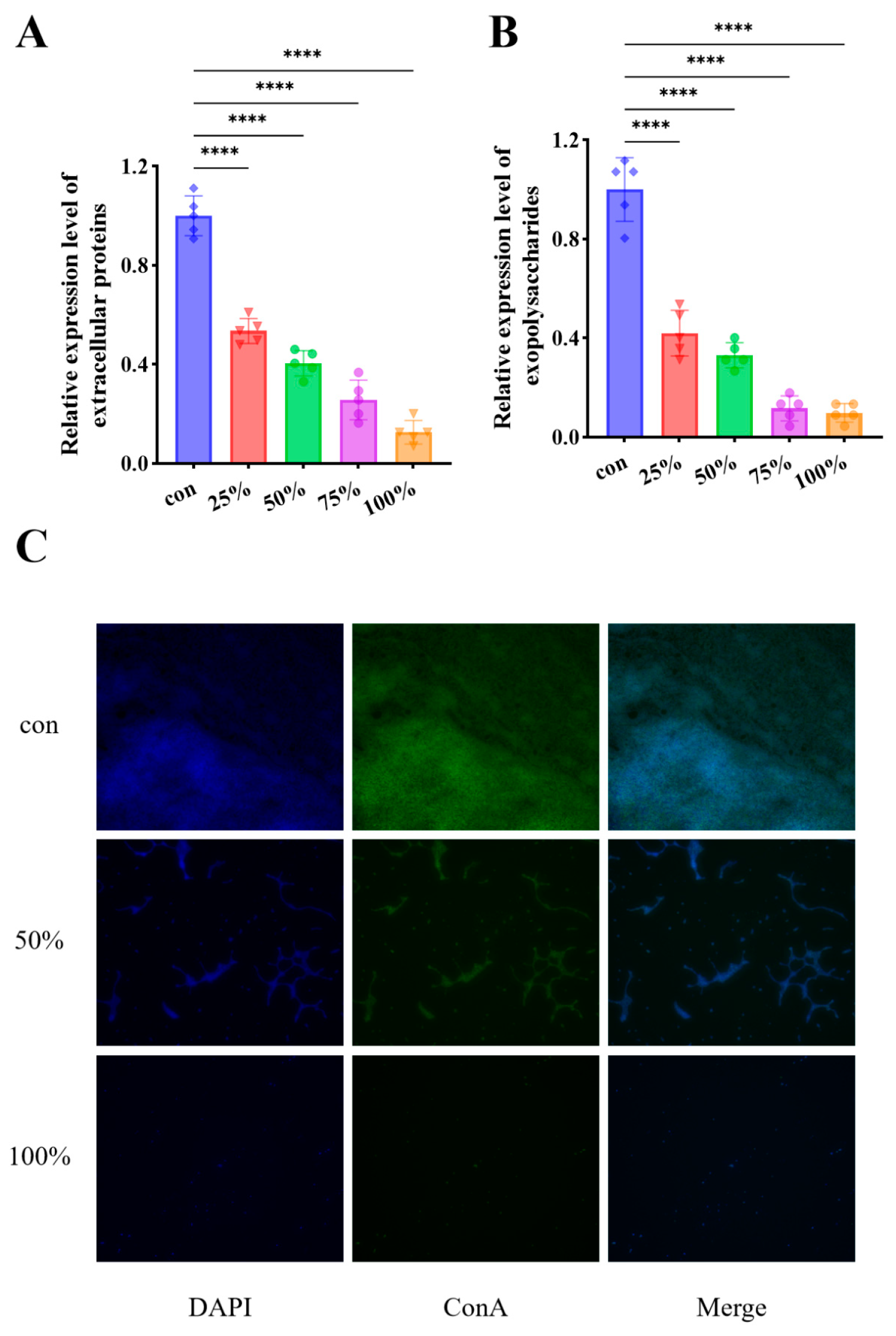

3.5. CFS Decreased the Secretion of EPS

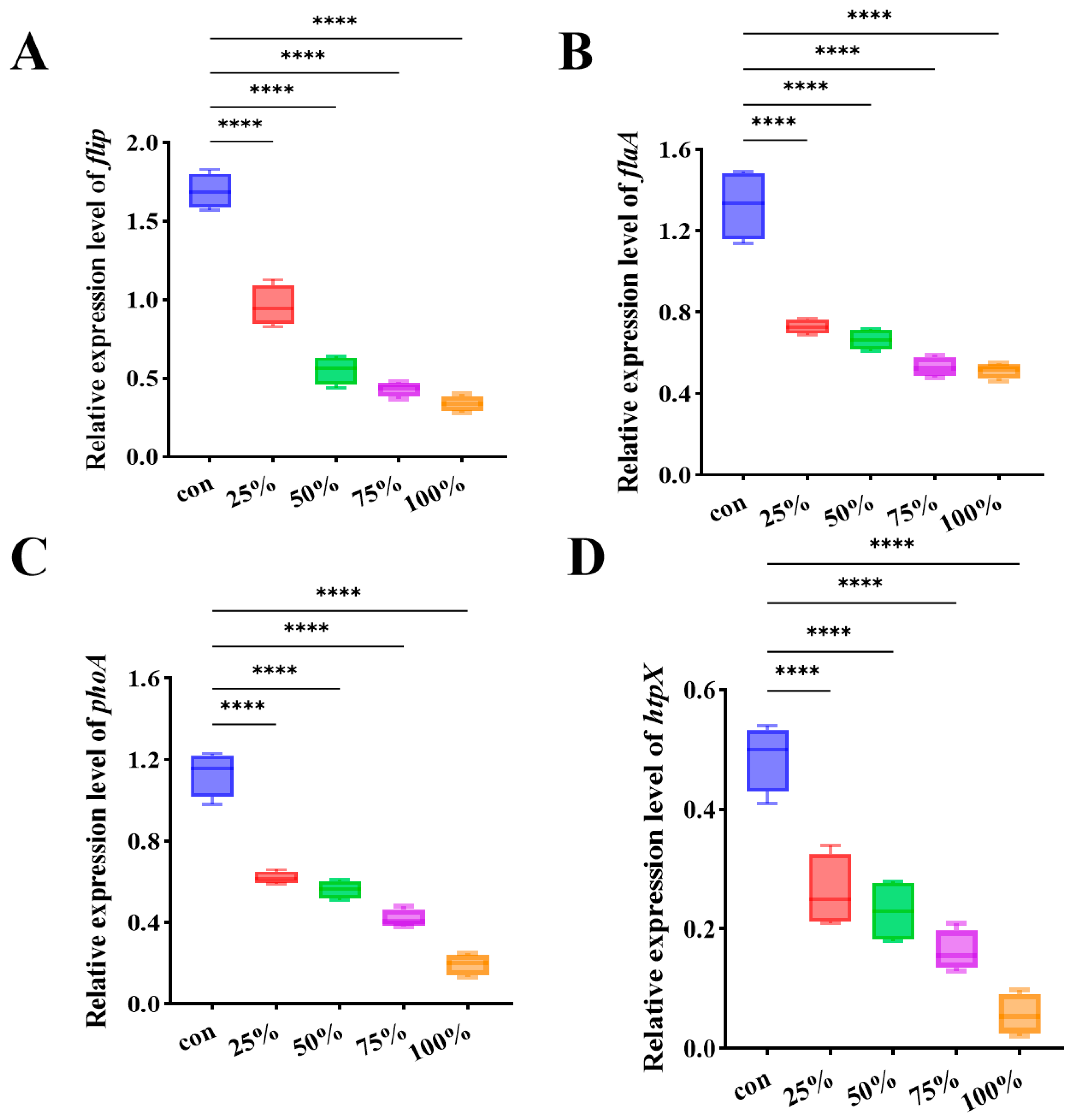

3.6. CFS Modulated the Expression of Biofilm and Motility Associated Genes in P. fluorescens

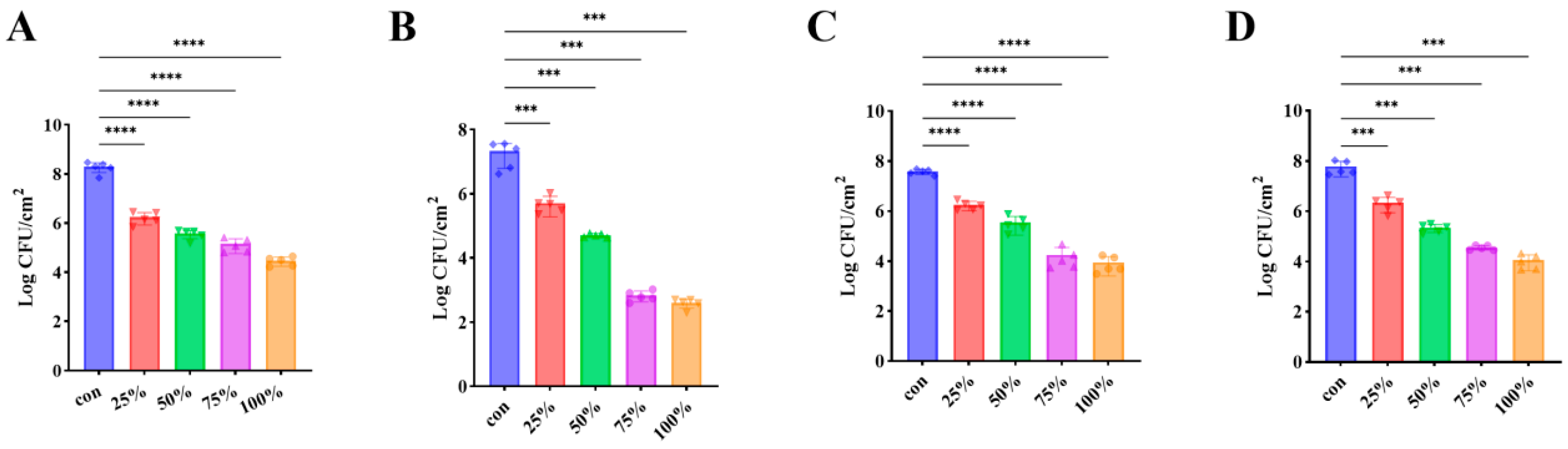

3.7. CFS Inhibited Biofilm Development of P. fluorescens on Diverse Food and Material Surfaces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snyder, A.B.; Martin, N.; Wiedmann, M. Microbial food spoilage: Impact, causative agents and control strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Franzetti, L.; Kaushal, A.; Kumar, D. Pseudomonas fluorescens: A potential food spoiler and challenges and advances in its detection. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, H.; Cassel, C.; Verma, A.; Poljak, A.; Charlton, T.; Aldrich-Wright, J.; Omar, S.M.; Siddiqui, K.S.; Cavicchioli, R. A new broad specificity alkaline metalloprotease from a Pseudomonas sp. isolated from refrigerated milk: Role of calcium in improving enzyme productivity. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 113, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinja, A.I.; Kamarudin, N.H.A.; Leow, A.T.C.; Oslan, S.N.; Ali, M.S.M. Cold-Active Lipases and Esterases: A Review on Recombinant Overexpression and Other Essential Issues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzi, L.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M.; Bevilacqua, A. Chapter 1—Microbial Spoilage of Foods: Fundamentals. In The Microbiological Quality of Food; Bevilacqua, A., Corbo, M.R., Sinigaglia, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, R.; Abdelhedi, O.; Nasri, M.; Jridi, M. Fermented protein hydrolysates: Biological activities and applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.P.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, Y.F. Study on the spoilage potential of Pseudomonas fluorescens on salmon stored at different temperatures. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Zhu, J.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Liu, X. Characterization of LuxI/LuxR and their regulation involved in biofilm formation and stress resistance in fish spoilers Pseudomonas fluorescens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 297, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, Z.; Jin, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Yu, H.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y. Role of siderophore in Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm formation and spoilage potential function. Food Microbiol. 2023, 109, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. Biofilm formation of Pseudomonas fluorescens induced by a novel diguanylate cyclase modulated c-di-GMP promotes spoilage of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Microbial biofilm: Formation, architecture, antibiotic resistance, and control strategies. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Piao, X.; Mahfuz, S.; Long, S.; Wang, J. The interaction among gut microbes, the intestinal barrier and short chain fatty acids. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 9, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, S.; Ji, X.; Wu, J.; Meng, J.; Gao, J.; Shao, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, G.; Qiu, J.; et al. Dubosiella newyorkensis modulates immune tolerance in colitis via the L-lysine-activated AhR-IDO1-Kyn pathway. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.T.J.; Gwynne, P.J.; Gallagher, M.P.; Simpson, A.H.R.W. The biofilm eradication activity of acetic acid in the management of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Jt. Res. 2018, 7, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen, N.M.; Maradagi, T.; Kavalappa, Y.P.; Sharma, H.; Ponesakki, G. Chapter 5—Seafood nutraceuticals: Health benefits and functional properties. In Research and Technological Advances in Food Science; Prakash, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Yang, W.; Chen, B.; Bao, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Qiu, L. Exploration of the primary antibiofilm substance and mechanism employed by Lactobacillus salivarius ATCC 11741 to inhibit biofilm of Streptococcus mutans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1535539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Xu, B.; Dai, B.; Yang, C. The Effects of Bacillus licheniformis on the Growth, Biofilm, Motility and Quorum Sensing of Salmonella typhimurium. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, T.; Knabbe, C.; Dreier, J. Dual-Temperature Microbiological Control of Cellular Products: A Potential Impact for Bacterial Screening of Platelet Concentrates? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, G. Impact of cell-free supernatant of lactic acid bacteria on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm and its metabolites. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1184989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, D.; Dong, X.; Hao, G.; Hu, Q.; Shami, A.; Al-Asmari, F.; Ma, S.; Ren, R.; Tan, Y. Potent antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of Lactobacillus plantarum X cell-free supernatant against foodborne pathogens and its application in aquatic product preservation. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Mahmud, M.L.; Almalki, W.H.; Biswas, S.; Islam, M.A.; Mortuza, M.G.; Hossain, M.A.; Ekram, M.A.-E.; Uddin, M.S.; Zaman, S.; et al. Cell-Free Supernatants (CFSs) from the Culture of Bacillus subtilis Inhibit Pseudomonas sp. Biofilm Formation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yuan, W.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F.; Xuan, H. Anti-Biofilm Activities of Chinese Poplar Propolis Essential Oil against Streptococcus mutans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Ren, B.; Dai, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y. Clotrimazole and econazole inhibit Streptococcus mutans biofilm and virulence in vitro. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 73, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yu, H.H.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Cell-free supernatants of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus polyfermenticus inhibit Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Food Control 2023, 144, 109387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatini, S.; Visconti, S.; Gentili, M.; Lusenti, E.; Nunzi, E.; Ronchetti, S.; Perito, S.; Gaziano, R.; Monari, C. Lactobacillus iners Cell-Free Supernatant Enhances Biofilm Formation and Hyphal/Pseudohyphal Growth by Candida albicans Vaginal Isolates. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Yu, H.H.; Song, Y.J.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Anti-biofilm effect of the cell-free supernatant of probiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae against Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 2021, 121, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, A.; Guo, J.; Jia, J.; Wang, H.; Xia, X. Antibiofilm activity of rosmarinic acid against Vibrio parahaemolyticus in vitro and its efficacy in food systems. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne, C.; Brun Yves, V. The Two Chemotaxis Clusters in Caulobacter crescentus Play Different Roles in Chemotaxis and Biofilm Regulation. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00071-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra Maillard, A.P.V.; Espeche, J.C.; Maturana, P.; Cutro, A.C.; Hollmann, A. Zeta potential beyond materials science: Applications to bacterial systems and to the development of novel antimicrobials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Dey, P. Bacterial exopolysaccharides as emerging bioactive macromolecules: From fundamentals to applications. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.; Itoh, K.; Misawa, N.; Ryu, S. Effects of Quorum Sensing on flaA Transcription and Autoagglutination in Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 47, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ru, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, W. cAMP and c-di-GMP synergistically support biofilm maintenance through the direct interaction of their effectors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cai, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Biofilm formation by meat-borne Pseudomonas fluorescens on stainless steel and its resistance to disinfectants. Food Control 2018, 91, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.M. Quaternary ammonium disinfectants and antiseptics: Tolerance, resistance and potential impact on antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2023, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Herranz-López, M.; Micol, V. Antibacterial plant compounds, extracts and essential oils: An updated review on their effects and putative mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, M.J.; Brubaker, T.R.; Honish, B.J., 2nd; Simmons, A.N.; Kazemi, A.; Geissel, M.A.; Whalen, C.T.; Siedlecki, C.A.; Bilén, S.G.; Knecht, S.D.; et al. Antibacterial effects of low-temperature plasma generated by atmospheric-pressure plasma jet are mediated by reactive oxygen species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.; Qi, B. Advancing Phage Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Safety, Efficacy, and Future Prospects for the Targeted Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 1127–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Activity and safety evaluation of natural preservatives. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukomanović, M.; Žunič, V.; Kunej, Š.; Jančar, B.; Jeverica, S.; Podlipec, R.; Suvorov, D. Nano-engineering the Antimicrobial Spectrum of Lantibiotics: Activity of Nisin against Gram Negative Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; He, R.; Hu, H.; Wu, B.; Ren, H. Bacterial assembly during the initial adhesion phase in wastewater treatment biofilms. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, A.; Levarski, Z.; Mikulášová, M.; Straka, M.; Liptáková, A.; Stuchlík, S. Complex Analysis of Vanillin and Syringic Acid as Natural Antimicrobial Agents against Staphylococcus epidermidis Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y.; Khanum, R. Antimicrobial peptides as potential anti-biofilm agents against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017, 50, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Gu, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, L. Flagellar motility mediates early-stage biofilm formation in oligotrophic aquatic environment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 194, 110340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Parsania, C.; Tan, K.; Todd, R.B.; Wong, K.H. Co-option of an extracellular protease for transcriptional control of nutrient degradation in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savairam, V.D.; Patil, N.A.; Borate, S.R.; Ghaisas, M.M.; Shete, R.V. Allicin: A review of its important pharmacological activities. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 8, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, A.; Cao, S.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Tang, G.Y.; Corke, H.; Mavumengwana, V.; Li, H.B. Bioactive Compounds and Biological Functions of Garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods 2019, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozma, M.A.; Khodadadi, E.; Pakdel, F.; Kamounah, F.S.; Yousefi, M.; Yousefi, B.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Ganbarov, K.; Kafil, H.S. Baicalin, a natural antimicrobial and anti-biofilm agent. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 27, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, I.A.; Dikhtyar, Y.Y.; Bogdanov, A.A.; Dontsova, O.A.; Sergiev, P.V. Regulation of Flagellar Gene Expression in Bacteria. Biochemistry 2015, 80, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitani, K.; Hizukuri, Y.; Akiyama, Y. An in vivo protease activity assay for investigating the functions of the Escherichia coli membrane protease HtpX. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagle, B.R.; Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Shrestha, S.; Arsi, K.; Liyanage, R.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Donoghue, D.J.; Donoghue, A.M. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde, Eugenol and Carvacrol Reduce Campylobacter jejuni Biofilms and Modulate Expression of Select Genes and Proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Hou, Y.; Ai, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, X. Gallic acid: Pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Primer | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| 16SrRNA | Forward | ACCGTCAAGGGACAAGCA |

| Reverse | GGGAGGCAGCAGTAGGGA | |

| htpX | Forward | TTCGGCTTCAACGGGTTCATGG |

| Reverse | GGTGCTGGTGCTCATCTTCGC | |

| phoA | Forward | TGTATAACCGCTCGCCGTTTATCG |

| Reverse | GTAGAAGTGCCCGTGCTGGATTG | |

| flaA | Forward | CTGGTATGAGTCGCCTTAG |

| Reverse | CATTTGCGGTGTTTGGTTTG | |

| flip | Forward | AACGGCATTCCAGATCGGCTTC |

| Reverse | AATCAGCGGCGACAGCATCATC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, A.; Zhang, M.; Gu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qin, N.; Xia, X. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacies of Cell-Free Supernatant of Dubosiella newyorkensis Against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Application in Food Systems. Foods 2026, 15, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030581

Wang A, Zhang M, Gu Y, Cheng Y, Qin N, Xia X. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacies of Cell-Free Supernatant of Dubosiella newyorkensis Against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Application in Food Systems. Foods. 2026; 15(3):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030581

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ailin, Meihan Zhang, Yunqi Gu, Yuanhang Cheng, Ningbo Qin, and Xiaodong Xia. 2026. "Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacies of Cell-Free Supernatant of Dubosiella newyorkensis Against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Application in Food Systems" Foods 15, no. 3: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030581

APA StyleWang, A., Zhang, M., Gu, Y., Cheng, Y., Qin, N., & Xia, X. (2026). Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacies of Cell-Free Supernatant of Dubosiella newyorkensis Against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Application in Food Systems. Foods, 15(3), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030581