Arsenic Species and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Ratios in the Japanese Diet—Dietary Markers of Seafood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

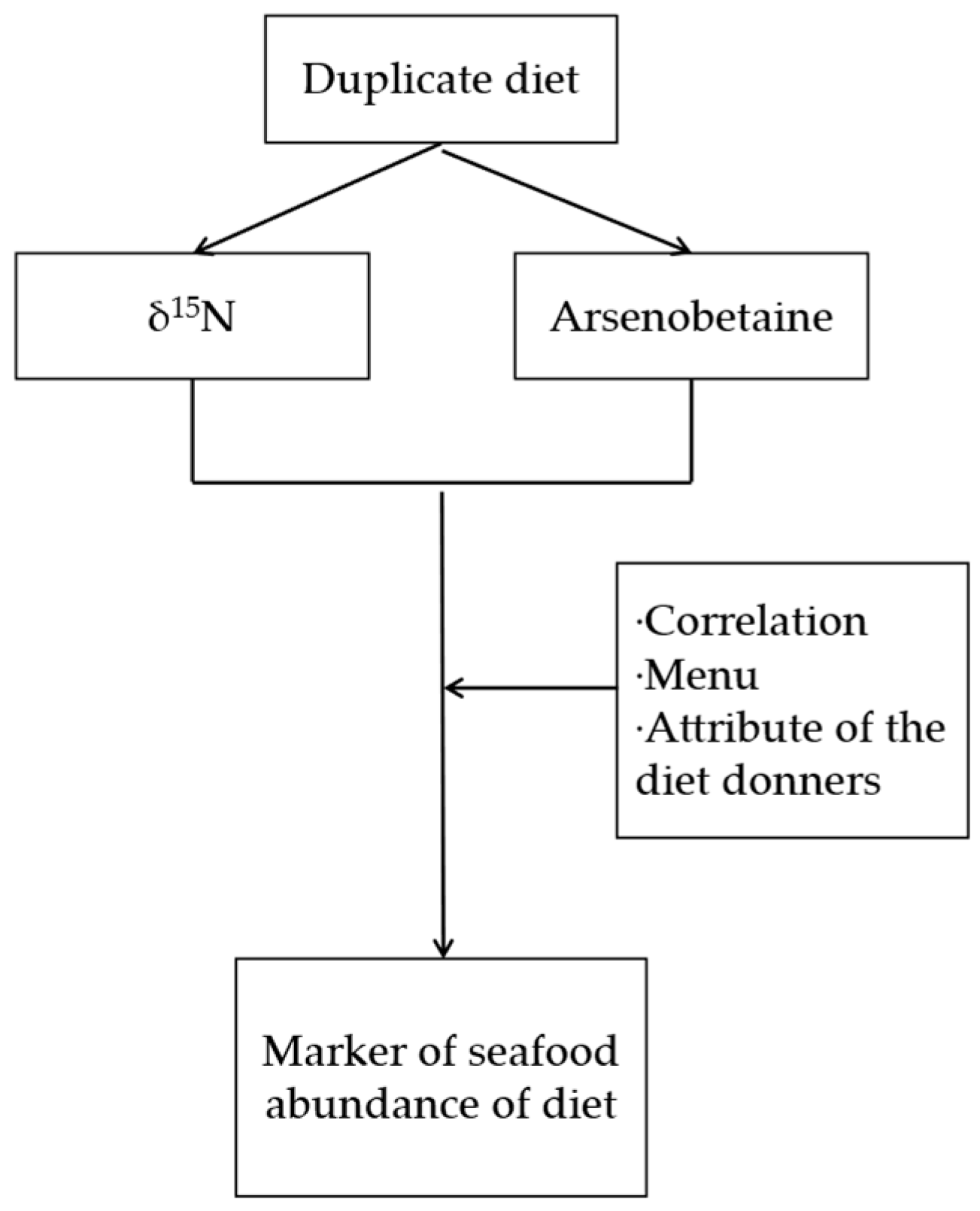

2.1. Overview of the Study

2.2. Duplicate Diet Samples

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

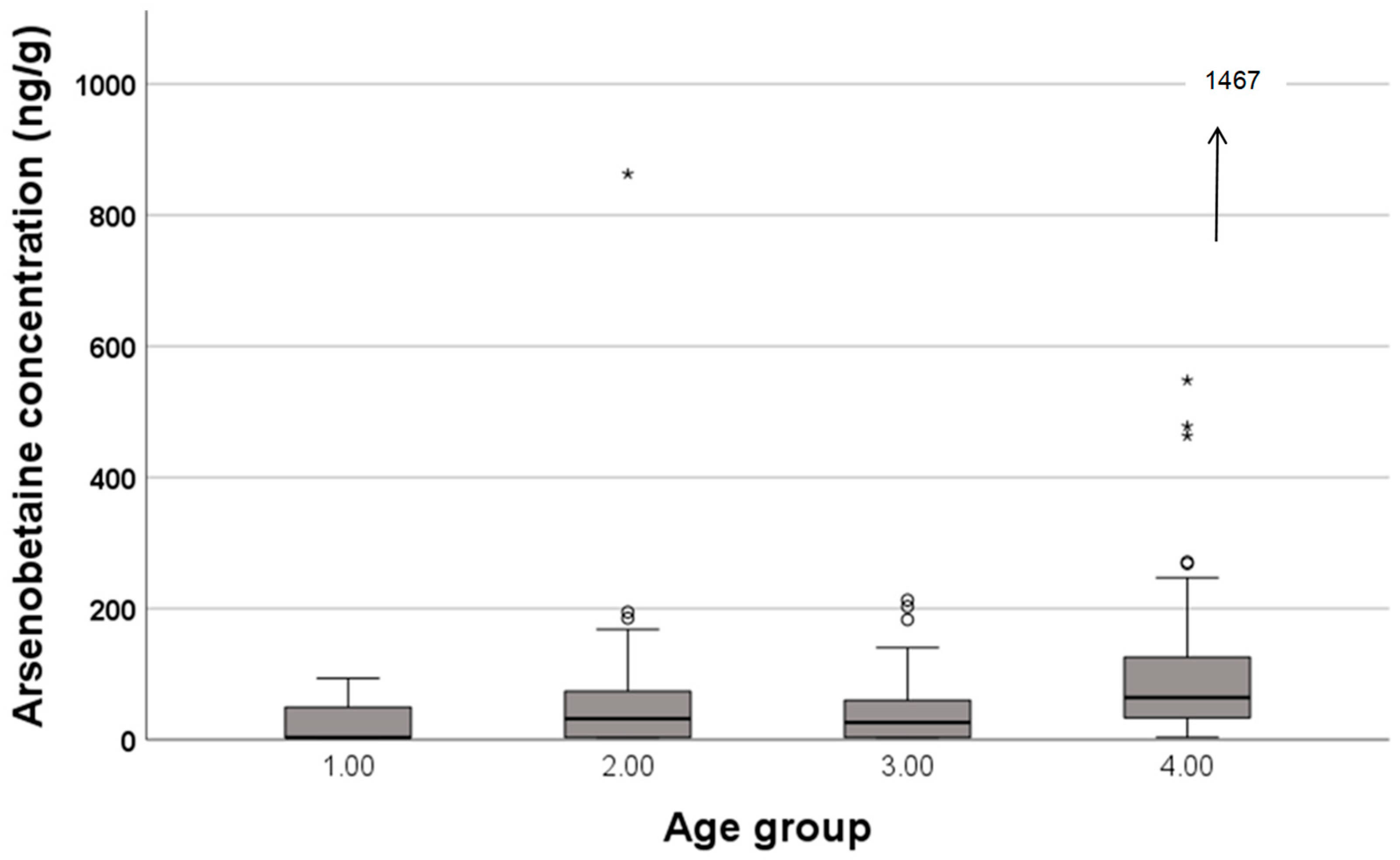

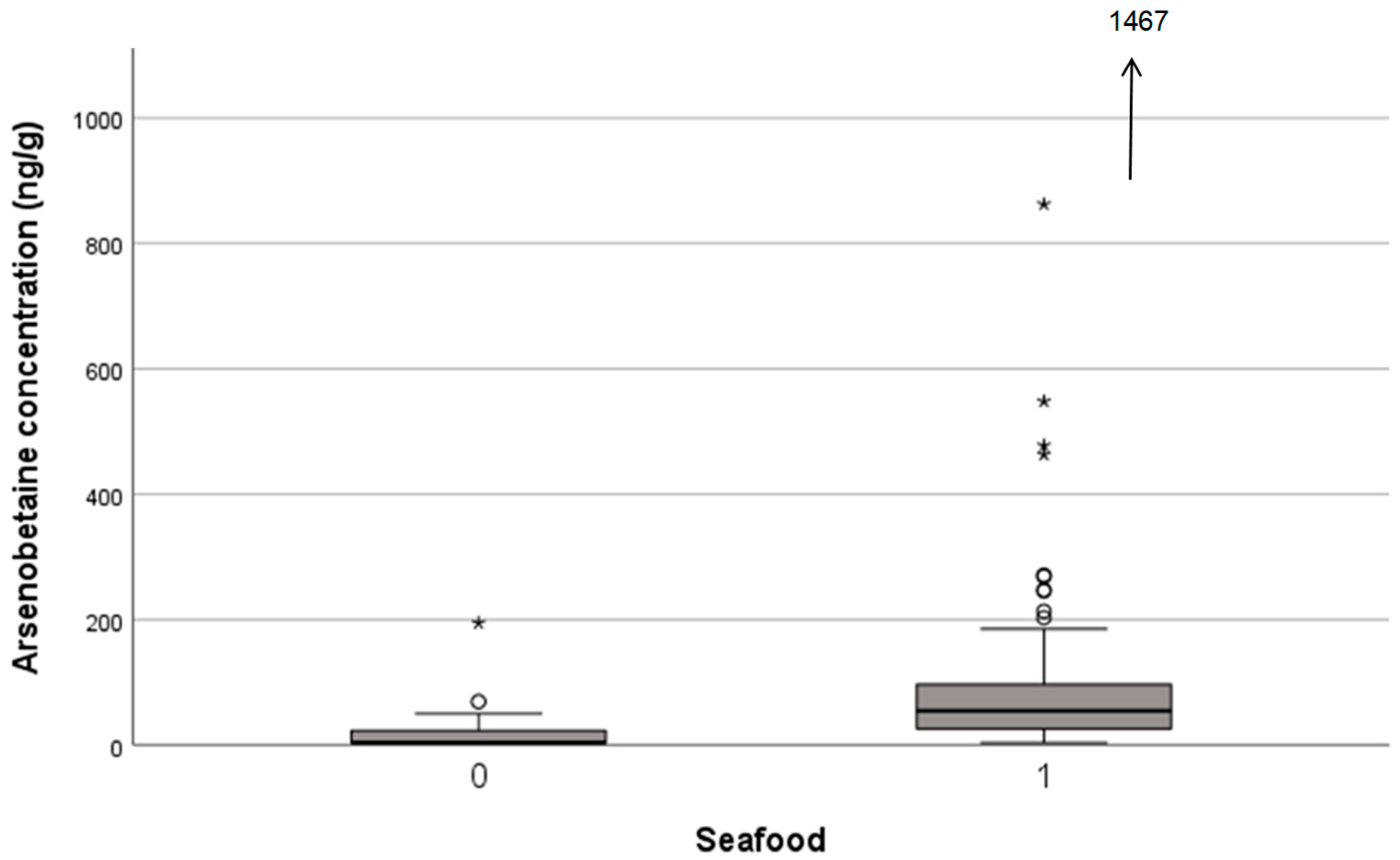

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maher, W.A. The presence of arsenobetaine in marine animals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 1985, 80, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, K.A.; Edmonds, J.S. Arsenic and marine organisms. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 44, 147–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kunito, T.; Kubota, R.; Fujiwara, J.; Agusa, T.; Tanabe, S. Arsenic in marine mammals, seabirds, and sea turtles. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 195, 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- Popowich, A.; Zhang, Q.; Chris Le, X. Arsenobetaine: The ongoing mystery. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2016, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, J.S.; Francesconi, K.A. Arseno-sugars from brown kelp (Ecklonia radiata) as intermediates in cycling of arsenic in a marine ecosystem. Nature 1981, 289, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Shibata, Y. Chemical form of arsenic in marine macroalgae. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1990, 4, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukai, R.; Maher, W.A.; McNaught, I.J.; Ellwood, K.J.; Coleman, M. Occurrence and chemical form of arsenic in marine macroalgae from the east coast of Australia. Mar. Fresh. Res. 2002, 53, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.; Krupp, E.M. Critical review of scientific opinion paper: Arsenosugars—A class of benign arsenic species or justification for developing partly speciated arsenic fractionation in foodstuffs? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Risk assessment of complex organoarsenic species in food. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9112.

- Amaral, C.D.B.; Nóbrega, J.A.; Nogueira, A.R.A. Sample preparation for arsenic speciation in terrestrial plants—A review. Talanta 2013, 115, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amore, T.; Miedico, O.; Pompa, C.; Preite, C.; Iammarino, M.; Nardelli, V. Characterization and quantification of arsenic species in foodstuffs of plant origin by HPLC/ICP-MS. Life 2023, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, K.; McDonald, R.A.; Bearhop, S. Application of stable isotope technique to the ecology of mammals. Mamm. Rev. 2008, 38, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S.; van der Molen, J. Trophic levels of marine consumers from nitrogen stable isotope analysis: Estimation and uncertainty. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 72, 2289–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.W.; Daniel, R.M. Fractionation of nitrogen isotopes by animals—A further compilation to use of variations in natural abundance of N-15 for tracer studies. J. Agric. Sci. 1978, 90, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, M.; Wada, E. Stepwise enrichment of 15N along food chains: Further evidence and the relation between δ15N and animal age. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heulsemann, F.; Koehler, K.; Braun, H.; Schaenzer, W.; Flenker, U. Human dietary δ15N intake: Representative data for principal food items. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop. 2013, 152, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeninger, M.J.; DeNiro, M.J.; Tauber, H. Stable nitrogen isotope ratios of bone collagen reflect marine and terrestrial components of prehistoric diet. Science 1983, 220, 1381–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H.; Drucker, D. Trophic level isotopic enrichment of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen: Case studies from recent and ancient terrestrial ecosystems. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2003, 13, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, R.E.M.; Reynard, L.M. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.H.; O’Connell, C. Differential relations between cognition and 15N isotopic content of hair in elderly people with dementia and controls. J. Gerontol. 2002, 57A, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.Y.; Lampe, J.W.; Tinker, L.F.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Niles, K.R.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Van Horn, L.; Prentice, R.L.; et al. Serum nitrogen and carbon stable isotope ratios meet biomarker criteria for fish and animal protein intake in a controlled feeding study of a Women’s Health Initiative Cohort. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1931–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Votruda, S.B.; Shaw, P.A.; Oh, E.J.; Venti, C.A.; Bonfiglio, S.; Krakoff, J.; O’Brien, M. Association of plasma, RBSs, and hair carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios with fish, meat, and sugar-sweetened beverage intake in a 12-wk inpatient feeding study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaga, J.; Narukawa, T. Association of dietary intake and urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic in the Japanese subjects. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 116, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinaga, J.; Narukawa, T. Dietary intake and urinary excretion of methylated arsenicals of Japanese adults consuming marine foods and rice. Food Addit. Contam. 2021, 38, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaga, J. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of duplicate diet of the Japanese. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 39, e10014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo, S.; Aureli, F.; Raggi, A.; Cubadda, F. Arsenic speciation in freshwater fish: Focus on extraction and mass balance. Talanta 2010, 81, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlejkovec, Z.; Byrne, A.R.; Stijve, T.; Goessler, W.; Irgolic, K.J. Arsenic compounds in higher fungi. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1997, 11, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuer, S.; Goessler, W. Arsenic species in mushrooms, with a focus on analytical methods for their determination—A critical review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1073, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stråvik, M.; Gustin, K.; Barman, M.; Levi, M.; Sandin, A.; Wold, A.E.; Sandberg, A.-S.; Kippler, M.; Vahter, M. Biomarkers of seafood intake during pregnancy—Pollutants versus fatty acids and micronutrients. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinaga, J.; Komatsuda, S.; Fujita, R.; Amin, M.H.A.; Oguri, T. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of diet of the Japanese and diet-hair offset values. Isotop. Environ. Health Stud. 2021, 57, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sotiropoulos, M.A.; Tonn, W.M.; Wassenaar, L.I. Effects of lipid extraction on stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of fish tissues: Potential consequences for food web studies. Ecol. Fresh. Fish 2004, 13, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.M.; Lutcavage, M.E. A comparison of carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of fish tissues following lipid extractions with non-polar and traditional chloroform/methanol solvent system. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 22, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguri, T.; Yoshinaga, J.; Tao, H.; Nakazato, T. Inorganic arsenic in the Japanese diet: Daily intake and source. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 66, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui, A.; Tsutsumi, C.; Toda, S. Some characters of water-soluble arsenic compounds in marine brown algae, HIJIKI (Hijikia fusiforme) and ARAME (Eisenia bicyclis). Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 1349–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. Arsenic in Foods. (Updated on 16 February 2022). Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syouan/nouan/kome/k_as/occurrence.html//www.maff.go.jp/j/syouan/nouan/kome/k_as/occurrence.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

| iAs (ng/g) | MMA (ng/g) | DMA (ng/g) | AB (ng/g) | δ15N (‰) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection frequency (%) | 100 | 0 | 64 | 74 | - |

| Mean | 83.6 | <6 | 17.2 | 77.1 | 3.58 |

| SD | 94.0 | - | 14.3 | 156.7 | 0.93 |

| Median | 60.2 | <6 | 14.8 | 35.9 | 3.42 |

| Min–Max | 2.9–652 | - | <6–66.5 | <7–1467 | 1.77–7.25 |

| Seafood | Seaweed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contain (n = 111) | Not Contain (n = 39) | U-Test | Contain (n = 87) | Not Contain (n = 63) | U-Test | |

| iAs, ng/g | 56.9 | 62.2 | NS | 66.9 | 48.3 | p < 0.01 |

| DMA, ng/g | 15.0 | 12.2 | NS | 17.2 | 9.1 | p < 0.05 |

| AB, ng/g | 54.6 | <7 | p < 0.001 | 41.0 | 27.3 | NS |

| δ15N, ‰ | 3.60 | 3.01 | p < 0.001 | 3.41 | 3.44 | NS |

| Age Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 yrs | 21–40 yrs | 41–60 yrs | <61 yrs | ||

| Seafood | Contain | 5 | 35 | 29 | 42 |

| Not contain | 6 | 21 | 8 | 4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoshinaga, J.; Narukawa, T. Arsenic Species and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Ratios in the Japanese Diet—Dietary Markers of Seafood. Foods 2026, 15, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030500

Yoshinaga J, Narukawa T. Arsenic Species and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Ratios in the Japanese Diet—Dietary Markers of Seafood. Foods. 2026; 15(3):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030500

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshinaga, Jun, and Tomohiro Narukawa. 2026. "Arsenic Species and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Ratios in the Japanese Diet—Dietary Markers of Seafood" Foods 15, no. 3: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030500

APA StyleYoshinaga, J., & Narukawa, T. (2026). Arsenic Species and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Ratios in the Japanese Diet—Dietary Markers of Seafood. Foods, 15(3), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030500