Adulteration Detection of Multi-Species Vegetable Oils in Camellia Oil Using SICRIT-HRMS and Machine Learning Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Preparation

2.2. SICRIT-HRMS Measurement

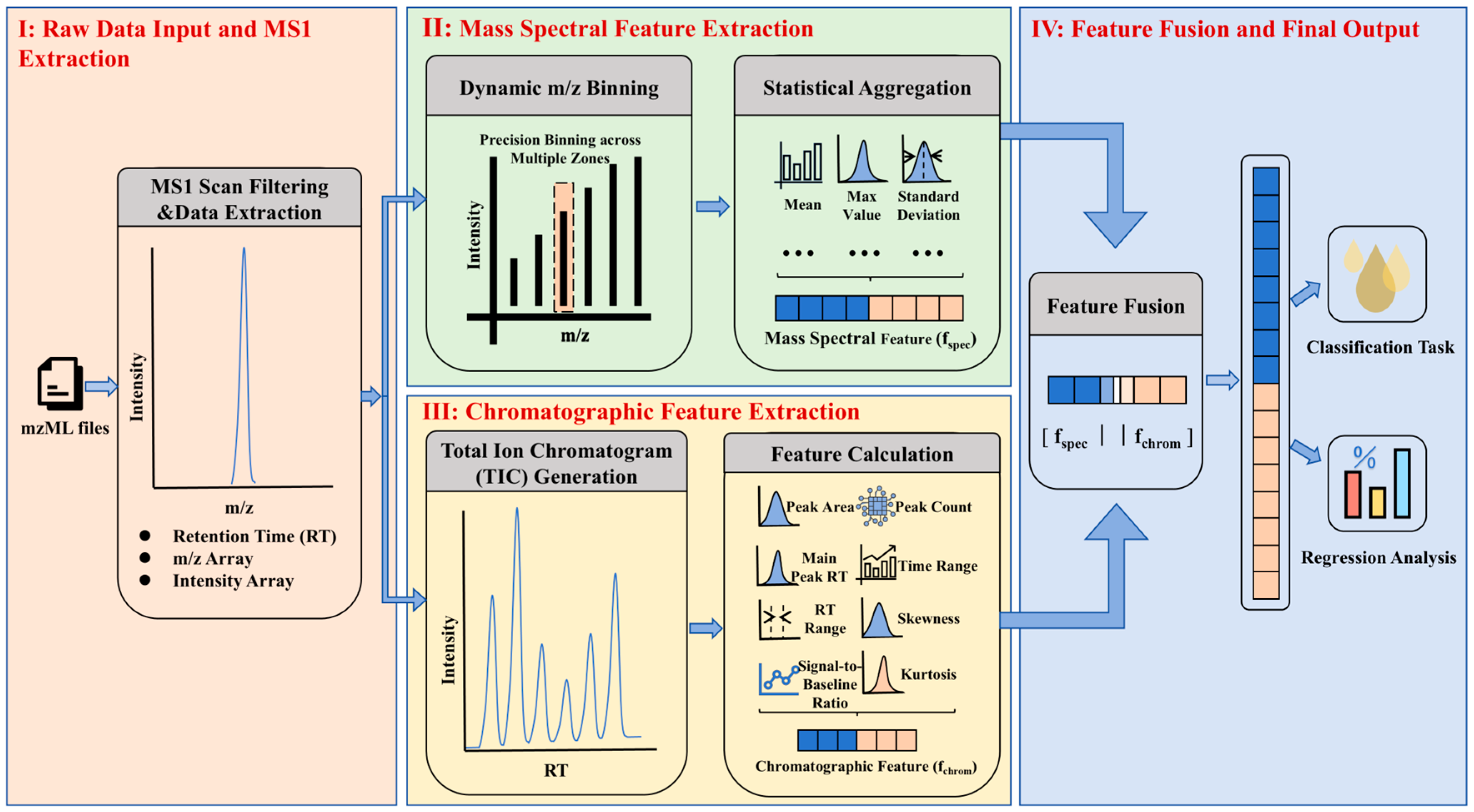

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.4.1. CNN Model

2.4.2. RF Model

2.4.3. SVM Model

2.4.4. LR Model

2.4.5. GBT Model

2.5. Training and Testing of Machine Learning Models

2.5.1. Qualitative Models

2.5.2. Quantitative Models

2.6. Classifier and Model Evaluation

2.6.1. Qualitative Model Evaluation

2.6.2. Quantitative Model Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

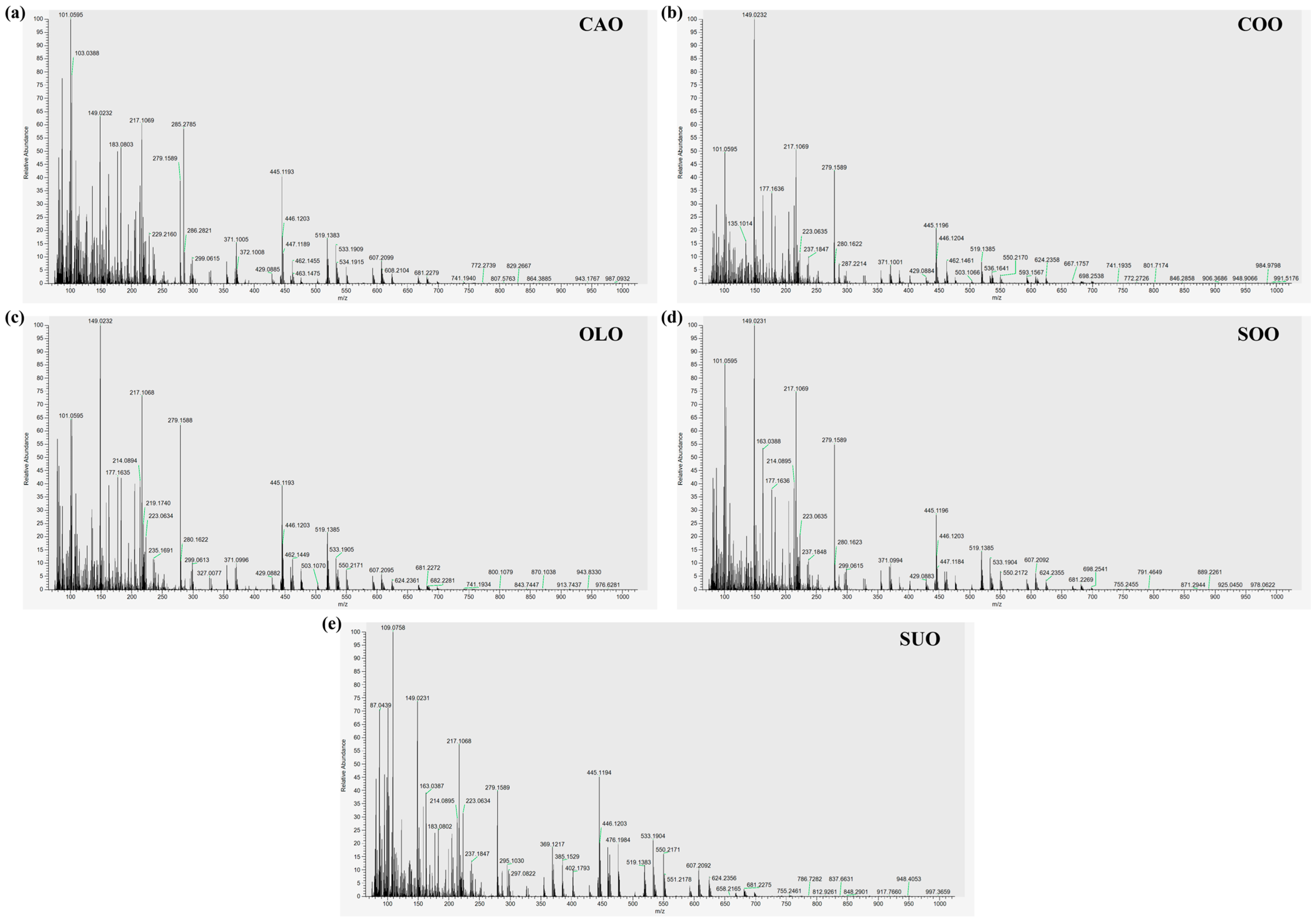

3.1. SICRIT-HRMS Fingerprint

3.2. Binary Qualitative Modeling for the Identification of Adulterated CAO

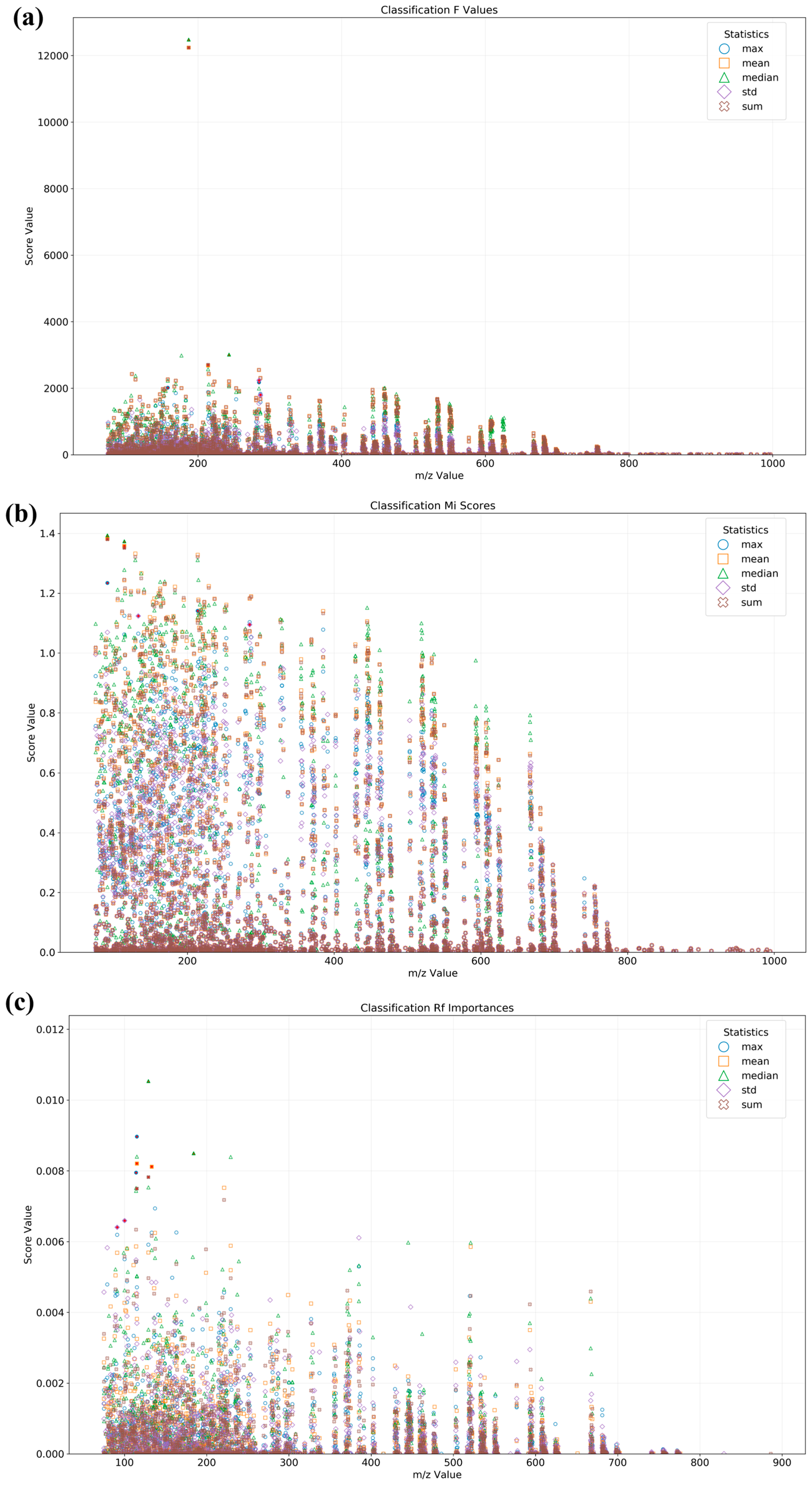

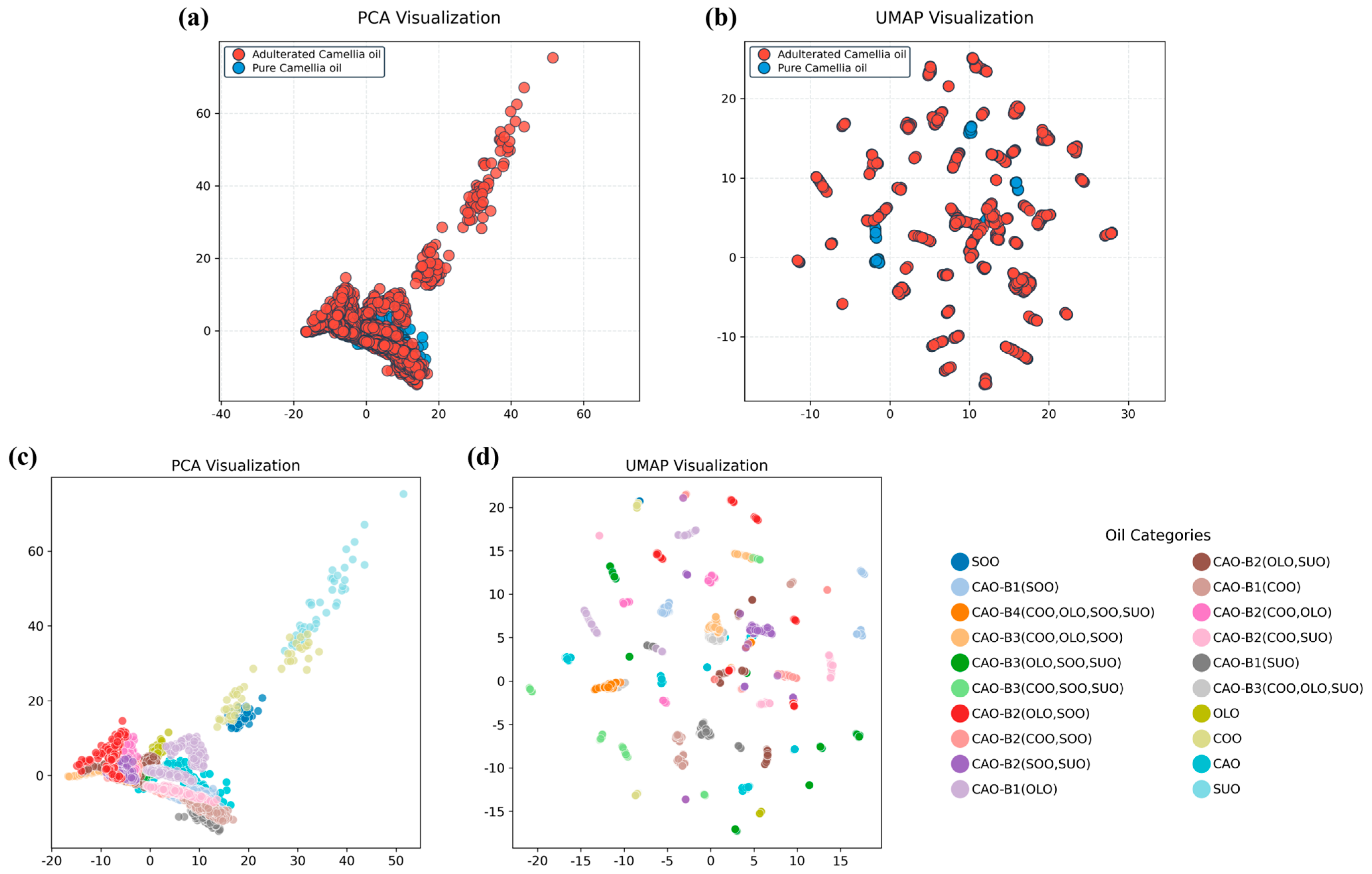

3.3. Multivariate Qualitative Modeling for the Identification of Adulterated CAO

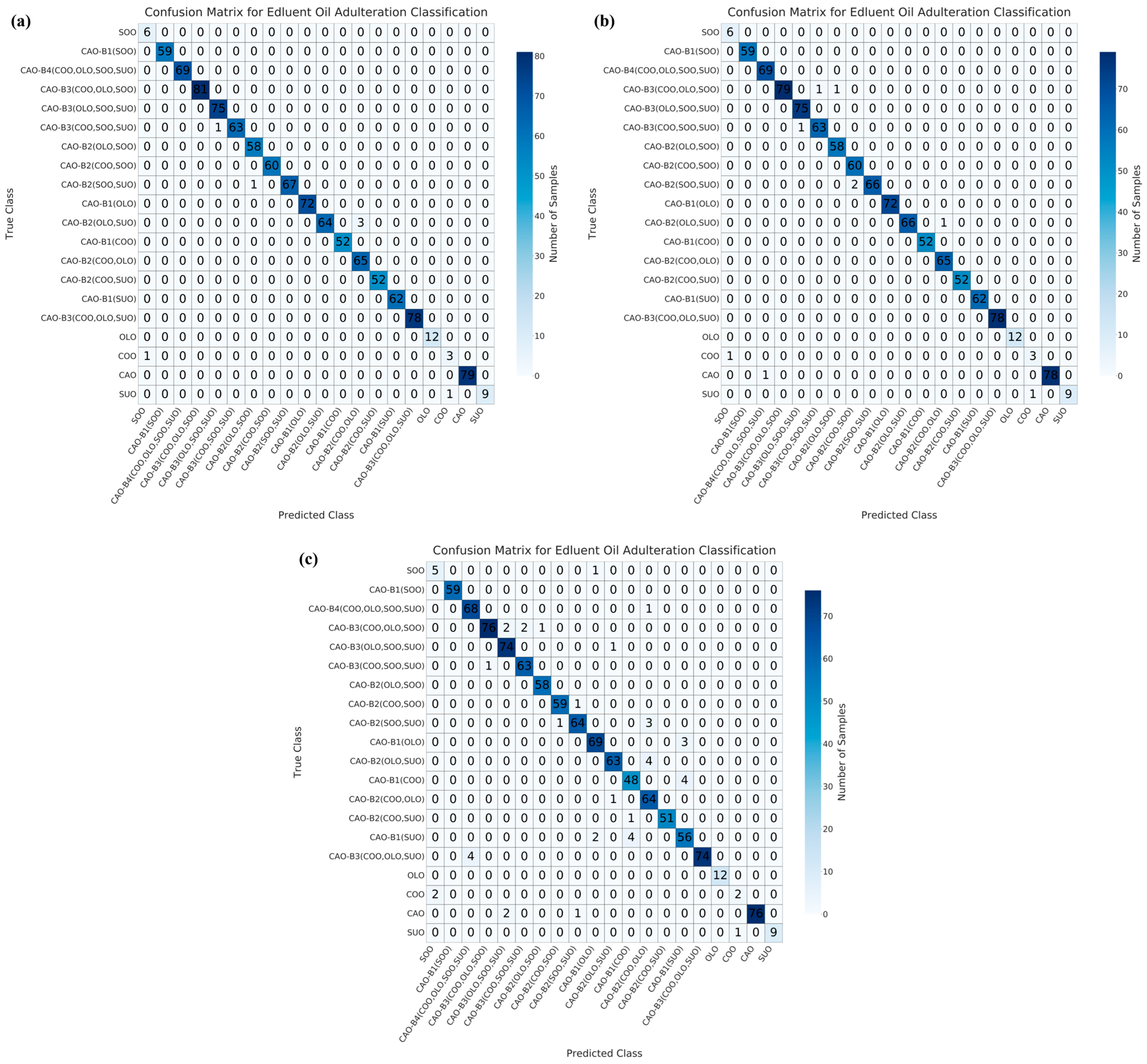

3.4. Data Fusion Combined with Machine Learning Analysis

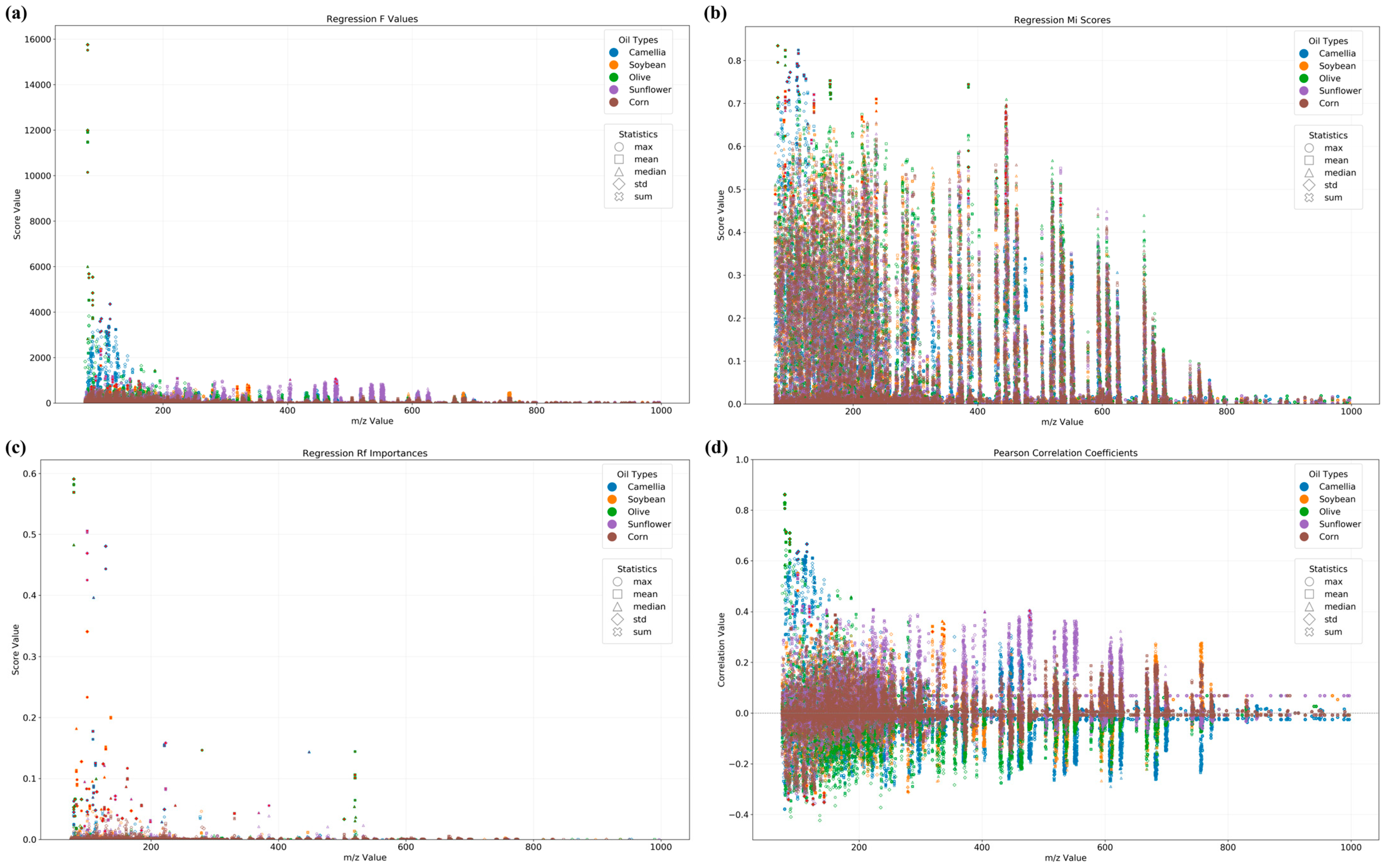

3.5. Quantitative Modeling for Adulteration Level Prediction of Adulterated CAO

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zou, Q.; Chen, A.Q.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Luo, J.H.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.Y. Edible plant oils modulate gut microbiota during their health-promoting effects: A review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1473648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, T.; Zhu, M.T.; Chen, Y.; Yan, X.L.; Chen, Q.; Wu, X.L.; Lin, J.N.; Xie, M.Y. 1H NMR combined with chemometrics for the rapid detection of adulteration in camellia oils. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Jin, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, K.; Lin, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Shen, Y. Recent advances in the extraction, composition analysis and bioactivity of Camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) oil. Trend. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wu, G.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Camellia oil authentication: A comparative analysis and recent analytical techniques developed for its assessment. A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wu, G.C.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Detection of camellia oil adulteration using chemometrics based on fatty acids GC fingerprints and phytosterols GC–MS fingerprints. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Zhang, M.J.; Koidis, A.; Liu, X.D.; Guo, C.Z.; Xu, Z.L.; Wei, X.Q.; Lei, H.T. Identification and quantitation of multiplex camellia oil adulteration based on 11 characteristic lipids using UPLC-Q-Orbitrap-MS. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.S.; Xiang, T.J.; Xu, Z.M.; Hou, H.N.; Ge, Y.C.; Lai, H.N.; Wang, D.L.; Yuan, T.L.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; et al. Rapid identification of multiplex camellia oil adulteration based on lipidomic fingerprint using laser assisted rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry and data fusion combined with machine learning. LWT 2025, 228, 118078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Dai, T.H.; Wu, G.C.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Camellia oil grading adulteration detection using characteristic volatile components GC-MS fingerprints combined with chemometrics. Food Control 2025, 169, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.W.; Zhu, M.T.; Shi, T.; Luo, X.; Gan, B.; Tang, L.J.; Chen, Y. Adulteration detection of corn oil, rapeseed oil and sunflower oil in camellia oil by in situ diffuse reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Control 2021, 121, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Qian, J.J.; Xu, M.T.; Ding, J.Y.; Yue, Z.; Ding, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Liu, X.D.; Pi, F.W. Adulteration detection of multi-species vegetable oils in camellia oil using Raman spectroscopy: Comparison of chemometrics and deep learning methods. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.W.; Zheng, Y.; Lan, T.; Zhang, L.X.; Yun, Y.H.; Song, W. Detection of camellia oil adulteration based on near-infrared spectroscopy and smartphone combined with deep learning and multimodal fusion. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Meng, X.H. Highly efficient authentication of edible oils by FTIR spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, H.L.; Long, W.J.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Chen, A.Q.; Yu, R.Q. Rapid identification and quantification of cheaper vegetable oil adulteration in camellia oil by using excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.P.; Nie, Q.L.; Huang, R.B.; Shi, J.; Ren, J.J.; You, R.Y.; Wang, H.F.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Y.D. A fast and highly efficient strategy for detection of camellia oil adulteration using machine learning assisted SERS. LWT 2024, 213, 117069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, R.N.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Yu, Y.; Ren, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.M. Quantitative analysis of multi-component adulteration in camellia oil by near-infrared spectroscopy combined with long short-term memory neural networks algorithm. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 148, 108359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.K.; Zhang, D.Y.; Geng, Y.Y.; Zhang, S.X.; Liu, Y.N.; Wang, J.H. Chemometrics analysis of camellia oil authenticity using LF NMR and fatty acid GC fingerprints. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.N.; Fang, Y.; Luo, W.F.; Chen, M.T.; Li, Z.M.; Yu, Y.; Ren, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.; Dong, H. Quantitative analysis of camellia oil binary adulteration using near infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 115018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Wei, C.J.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Jia, B.B.; Jiao, Y.N. Identification of camellia oil adulteration by using near infrared spectroscopy combined with two dimensional correlation spectroscopy (2DCOS) analysis. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 149, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifna, E.J.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; Rao, K.V.S.; Dwivedi, M.; Kumar, M.; Thirumdas, R.; Ramesh, S.V. Advanced process analytical tools for identification of adulterants in edible oils—A review. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.G.; Zhao, J.Y.; Xue, H.Y.; Ma, Q. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry for food analysis: Recent progress and applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 178, 117814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.J.; Zhang, L.X.; Yang, R.N.; Wang, X.; Yu, L.; Yue, X.F.; Ma, F.; Mao, J.; Wang, X.P.; Zhang, W.; et al. Mass spectrometry in food authentication and origin traceability. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, 42, 1772–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.; Su, H.; Chang, T.H.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Sun, W.J.; Shiea, J. Rapid characterization and classification of edible oils with ambient ionization mass spectrometry combined with principal component analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 140, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubert, J.; Zachariasova, M.; Hajslova, J. Advances in high-resolution mass spectrometry based on metabolomics studies for food—A review. Food Addit. Contam. A 2015, 32, 1685–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilla-Casas, B.Q.; Strocchi, G.; Bustamante, J.B.; Torres-Cobos, B.; Guardiola, F.I.; Moreda, W.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Toschi, T.G.; et al. Large-scale evaluation of shotgun triacylglycerol profiling for the fast detection of olive oil adulteration. Food Control 2021, 123, 107851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanna, D.; Hurkova, K.; Džuman, Z.; Serani, A.; Serani, M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Tomaniova, M.; Hajslova, J.; Suman, M. A Non-Targeted High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Study for Extra Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration with Soft Refined Oils: Preliminary Findings from Two Different Laboratories. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 24169–24178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.S.; Yang, N.; Guo, C.T.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Yu, J.J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; et al. Rapid and Eco-Friendly Quality Grading of Sauce-Aroma Baijiu Using Soft Ionization by Chemical Reaction in Transfer-Quadrupole Orbitrap HRMS Fingerprinting. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 3293–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basham, V.; Hancock, T.; McKendrick, J.; Tessarolo, N.; Wicking, C. Detailed chemical analysis of a fully formulated oil using dielectric barrier discharge ionisation–mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 36, e9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, M.; Frömel, T.; Knepper, T.P.; Huhn, C.; Wagner, S.; Pütz, M. Rapid Assessment of Samples from Large-Scale Clandestine Synthetic Drug Laboratories by Soft Ionization by Chemical Reaction in Transfer–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pu, H.B.; Sun, D.W. Efficient extraction of deep image features using convolutional neural network (CNN) for applications in detecting and analysing complex food matrices. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 113, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.C.; Jiang, H. Monitoring of chlorpyrifos residues in corn oil based on Raman spectral deep-learning model. Foods 2023, 12, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.X.; Wu, D.; Chen, B.; Yuan, H.B.; Yu, H.Y.; Lou, X.M.; Chen, C. Rapid identification and quantification of vegetable oil adulteration in raw milk using a flash gas chromatography electronic nose combined with machine learning. Food Control 2023, 150, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santana, F.B.; Borges Neto, W.; Poppi, R.J. Random forest as one-class classifier and infrared spectroscopy for food adulteration detection. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavali, A.; Rahmatpanahi, A.; Chegini, R.M. Quantitative detection of adulteration in avocado oil using laser-induced fluorescence and machine learning models. Microchem. J. 2025, 211, 113080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmi, F.; Dalai, A.K.; Hu, Y.F. Comparison of various machine learning techniques for modeling the heterogeneous acid-catalyzed alcoholysis process of biodiesel production from green seed canola oil. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucos, A.M.; Iantovics, L.B. Comparative study of random forest, gradient boosted trees, feedforward neural networks and convolutional neural networks using fingerprints and molecular descriptors for adverse drug reaction prediction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Z.; Hu, Y.R.; Sun, X.R.; Liu, C.L.; Yan, S.N.; Jiang, C.Z.; Zhou, X.P.; Liu, X.C.; Zhao, K. Identification and discrimination of olive oil adulteration by oblique-incidence reflectivity difference method. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Wang, M.; Zou, X.G.; Peng, B.; Yin, Y.L.; Deng, Z.Y. A Novel Aqueous Extraction for Camellia Oil by Emulsified Oil: A Frozen/Thawed Method. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 121, 1800431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.D.; Dong, Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Wang, X.D. Differences in Oxidative Stability, Sensory Properties, and Volatile Compounds of Pepper Aromatized Sunflower Oils Prepared by Different Methods during Accelerated Storage. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2023, 125, 2200099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Wang, S.; Tamogami, S.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, H. Volatile Profile and Flavor Characteristics of Ten Edible Oils. Anal. Lett. 2021, 54, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikhah, M.; Sarno, R.; Sabilla, S.I. Ensemble Learning for Optimizing Classification of Pork Adulteration in Beef Based on Electronic Nose Dataset. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2021, 14, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Y.; Bao, K.W.; Li, H.S.; Li, F.J.; Wang, X.P.; Cao, L.X.; Li, G.M.; Zhou, Q.; Tang, H.X.; Bao, M.T. An efficient classification method for fuel and crude oil types based on m/z 256 mass chromatography by COW-PCA-LDA. Fuel 2018, 222, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damirchi, S.A.; Savage, G.P.; Dutta, P.C. Sterol fractions in hazelnut and virgin olive oils and 4,4′-dimethylsterols as possible markers for detection of adulteration of virgin olive oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2005, 82, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.Z.; Song, K.; Gong, Y.Z.; Sheng, D.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Yan, S.Y.; Yan, S.C.; Zhang, J.S.; Tan, Y.; et al. Detailed speciation of semi-volatile and intermediate-volatility organic compounds (S/IVOCs) in marine fuel oils using GC × GC-ms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Wu, Q.Y.; Kamruzzaman, M. Portable NIR spectroscopy and PLS based variable selection for adulteration detection in quinoa flour. Food Control 2022, 138, 108970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqeel, M.; Sohaib, A.; Iqbal, M.; Rehman, H.U.; Rustam, F. Hyperspectral identification of oil adulteration using machine learning techniques. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.B.; Song, L.F.; Zhang, Y.L.; Dai, J.W.; Liu, Y.W.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, W.; Yan, J. A comparative study of fluorescence hyperspectral imaging and FTIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics for the detection of extra virgin olive oil adulteration. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 1761–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.T.; Wei, C.J.; Wang, X.R.; Wang, W.; Jiao, Y.N. Using three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning for rapid detection of adulteration in camellia oil. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 329, 125524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqeel, M.; Munawar, H.; Sohaib, A.; Khan, K.B.; Deng, Y.M. Spectral band selection for nondestructive detection of edible oil adulteration using hyperspectral imaging and chemometric analysis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachie, C.Y.E.; Obiri-Ananey, D.; Alfaro-Cordoba, M.; Tawiah, N.A.; Aryee, A.N.A. Classification of oils and margarines by FTIR spectroscopy in tandem with machine learning. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.; Xue, M.M.; Yuan, Y.Z.; Shi, H.W. Machine learning-assisted classification and adulteration detection of fatty oils using fatty acid profiles obtained via supercritical fluid chromatography. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2025, 265, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.J.; Wang, W.; Jiao, Y.N.; Yoon, S.C.; Ni, X.Z.; Wang, X.R.; Song, Z.W. Identification of Camellia Oil Adulteration with Excitation-Emission Matrix Fluorescence Spectra and Deep Learning. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 9175–9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.Y.; Long, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.W.; Zou, B.; Xu, L.J. Rapid identification of adulterated safflower seed oil by use of hyperspectral spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Lett. 2021, 54, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.P.; Jiang, H.; Yang, G.; Gong, Z.L.; Wen, T. Qualitative and quantitative detection of camellia oil adulteration using electronic nose based on wavelet decomposition humidity correction. LWT 2024, 210, 116822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Q.; Wu, H.L.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.Z.; Sun, H.B.; Yu, R.Q. Intelligent analysis of excitation-emission matrix fluorescence fingerprint to identify and quantify adulteration in camellia oil based on machine learning. Talanta 2023, 251, 123733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ma, S.A.; Liang, N.; Wang, X. Quantitatively Detecting Camellia Oil Products Adulterated by Rice Bran Oil and Corn Oil Using Raman Spectroscopy: A Comparative Study Between Models Utilizing Machine Learning Algorithms and Chemometric Algorithms. Foods 2024, 13, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.X.; Chen, G.Q.; Ma, C.Q.; Zhu, C.; Li, L.; Gao, H.; Yang, T.Q. Quantitative determination of acid value in palm oil during thermal oxidation using Raman spectroscopy combined with deep learning models. Food Chem. 2025, 474, 143107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, I.A.; Junior, S.B.; Villa, J.E.L.; Cunha, R.L.; Barbin, D.F. Predicting oleogels properties using non-invasive spectroscopic techniques and machine learning. Food Res. Int. 2025, 207, 116044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Bustamante, J.; Guardiola, F.; García-González, D.L.; Barbieri, S.; Bendini, A.; Toschi, T.G.; Vichi, S.; Tres, A. Virgin olive oil volatile fingerprint and chemometrics: Towards an instrumental screening tool to grade the sensory quality. LWT 2020, 121, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, A.; Camerlingo, A.; Sanna, N.; Zazza, C.; Benelli, A.; Massantini, R.; Moscetti, R. Comparing deep and classical Chemometrics: Can CNN enhance the accuracy of EVOO adulteration detection from spectral data? Food Control 2026, 179, 111608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gong, Z.L.; Li, D.P.; Wen, T.; Guan, J.W.; Zheng, W.F. Rapid and Low-Cost Quantification of Adulteration Content in Camellia Oil Utilizing UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy Combined with Feature Selection Methods. Molecules 2023, 28, 5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensionality Reduction Method | Model | Accuracy/% | Precision/% | Recall/% | F1-Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON | CNN | 99.95 | 99.91 | 100.00 | 0.9996 | 1.0000 |

| RF | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SVM | 86.26 | 83.35 | 91.94 | 0.8743 | 0.9449 | |

| LR | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| GBT | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| PCA | CNN | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| RF | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SVM | 81.79 | 87.49 | 75.81 | 0.8123 | 0.8967 | |

| LR | 98.51 | 98.74 | 98.39 | 0.9856 | 0.9997 | |

| GBT | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| UMAP | CNN | 98.70 | 99.28 | 98.21 | 0.9874 | 0.9958 |

| RF | 99.49 | 99.20 | 99.82 | 0.9951 | 0.9952 | |

| SVM | 52.21 | 53.68 | 58.78 | 0.5612 | 0.5890 | |

| LR | 81.51 | 86.80 | 75.99 | 0.8103 | 0.8657 | |

| GBT | 99.49 | 99.20 | 99.82 | 0.9951 | 0.9965 |

| Dimensionality Reduction Method | Model | Accuracy/% | Precision/% | Recall/% | F1-Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON | CNN | 99.09 | 97.40 | 97.68 | 0.9749 | 1.0000 |

| RF | 99.45 | 99.47 | 99.45 | 0.9945 | 1.0000 | |

| SVM | 99.27 | 99.29 | 99.27 | 0.9927 | 1.0000 | |

| LR | 98.44 | 98.48 | 98.44 | 0.9845 | 0.9999 | |

| GBT | 99.36 | 99.39 | 99.36 | 0.9936 | 1.0000 | |

| PCA | CNN | 99.54 | 97.80 | 98.03 | 0.9787 | 0.9998 |

| RF | 99.36 | 99.39 | 99.36 | 0.9936 | 1.0000 | |

| SVM | 99.18 | 99.20 | 99.18 | 0.9918 | 1.0000 | |

| LR | 98.35 | 98.42 | 98.35 | 0.9836 | 0.9999 | |

| GBT | 99.18 | 99.20 | 99.18 | 0.9918 | 1.0000 | |

| UMAP | CNN | 93.87 | 88.53 | 89.48 | 0.8867 | 0.9965 |

| RF | 96.25 | 96.30 | 96.25 | 0.9624 | 0.9938 | |

| SVM | 92.50 | 93.26 | 92.50 | 0.9253 | 0.9957 | |

| LR | 92.77 | 93.54 | 92.77 | 0.9281 | 0.9955 | |

| GBT | 96.07 | 96.17 | 96.07 | 0.9607 | 0.9967 |

| Model | Training Datasets | Prediction Datasets | RPD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEC (%) | RMSEP (%) | ||||

| NON-CNN | 0.9948 ± 0.0012 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.9867 ± 0.0012 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.4 |

| PCA-CNN | 0.9958 ± 0.0004 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9937 ± 0.0012 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 1.1 |

| UMAP-CNN | 0.9664 ± 0.0017 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 0.9599 ± 0.0022 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| Types | Training Datasets | Prediction Datasets | RPD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEC (%) | RMSEP (%) | ||||

| COO | 0.9845 ± 0.0021 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9765 ± 0.0061 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.8 |

| OLO | 0.9974 ± 0.0001 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.9963 ± 0.0002 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 16.3 ± 0.4 |

| SOO | 0.9844 ± 0.0022 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9794 ± 0.0056 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.9 |

| SUO | 0.9965 ± 0.0002 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.9901 ± 0.0062 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 11.3 ± 3.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Liu, T.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.-B.; Zou, Q.; Liu, H.-C.; Wang, X.-Y. Adulteration Detection of Multi-Species Vegetable Oils in Camellia Oil Using SICRIT-HRMS and Machine Learning Methods. Foods 2026, 15, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030434

Wang M, Liu T, Liao H, Liu X-B, Zou Q, Liu H-C, Wang X-Y. Adulteration Detection of Multi-Species Vegetable Oils in Camellia Oil Using SICRIT-HRMS and Machine Learning Methods. Foods. 2026; 15(3):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030434

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Mei, Ting Liu, Han Liao, Xian-Biao Liu, Qi Zou, Hao-Cheng Liu, and Xiao-Yin Wang. 2026. "Adulteration Detection of Multi-Species Vegetable Oils in Camellia Oil Using SICRIT-HRMS and Machine Learning Methods" Foods 15, no. 3: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030434

APA StyleWang, M., Liu, T., Liao, H., Liu, X.-B., Zou, Q., Liu, H.-C., & Wang, X.-Y. (2026). Adulteration Detection of Multi-Species Vegetable Oils in Camellia Oil Using SICRIT-HRMS and Machine Learning Methods. Foods, 15(3), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030434