Valorization of Hemp, Shrimp and Blue Crab Co-Products as Novel Culture Media Ingredients to Improve Protein Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Cultured Meat in Cell-Based Food Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Production of Plant- and Animal-Derived Hydrolysates

2.2.2. Antioxidant Activity of Hydrolysates

2.2.3. Sample Preparation for Cell Culture

2.2.4. Cell Viability and Proliferation

2.2.5. Cell Morphology

2.2.6. Determination of Protein Concentration in Exhausted Cell Culture Media and Cell Biomass

2.2.7. Determination of Antioxidant Activity in Exhausted Cell Culture Media and Cell Biomass

- (a)

- Acetate buffer (300 mM, pH 3.6): 2.69 g of sodium acetate trihydrate dissolved in 16 mL of glacial acetic acid, final volume brought to 1 L with distilled water.

- (b)

- 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) solution (10 mM): 31.2 mg of TPTZ dissolved in 10 mL of 40 mM HCl.

- (c)

- FeCl3·6H2O solution (20 mM): 0.054 g dissolved in 10 mL of distilled water.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

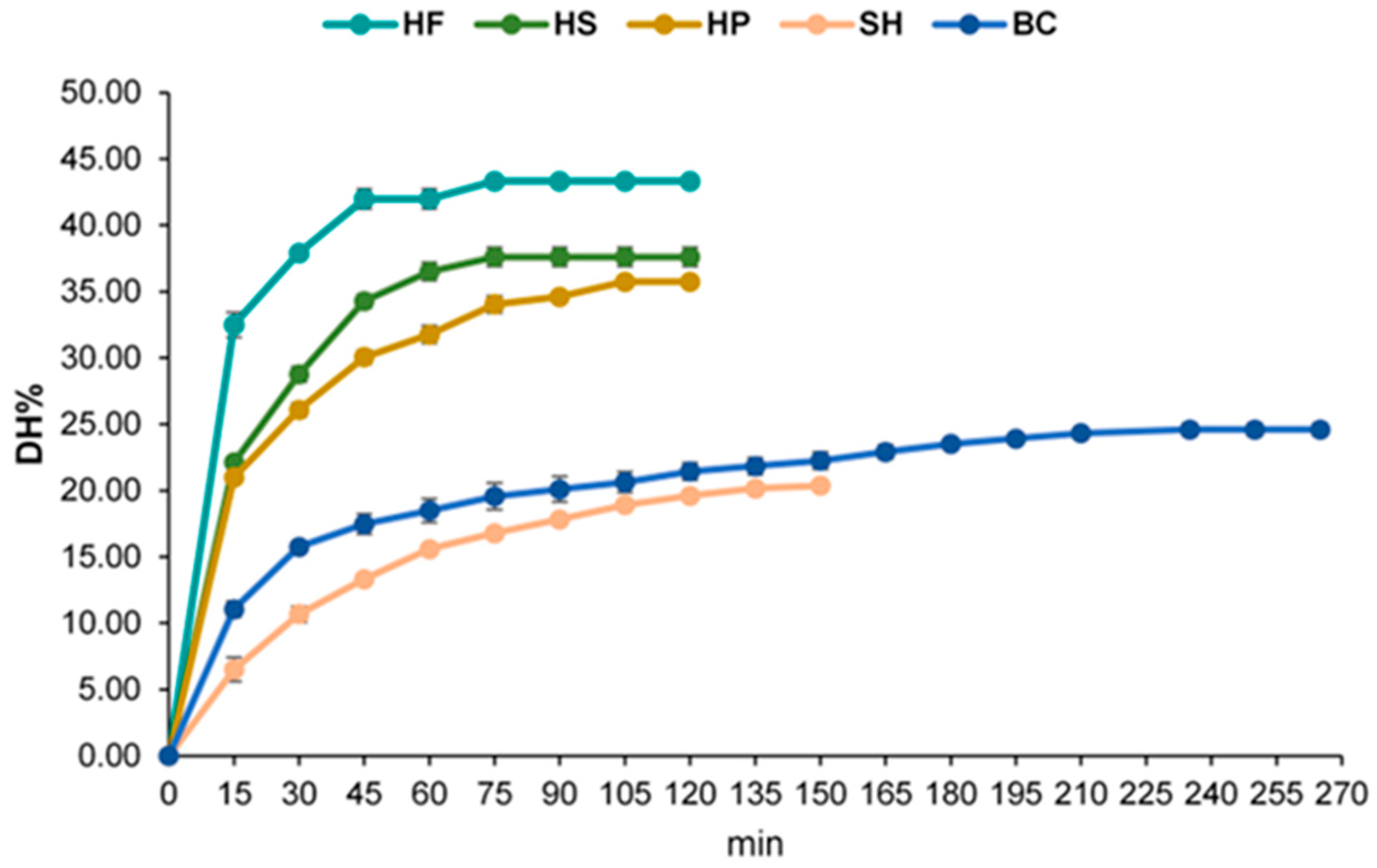

3.1. Production of Plant- and Animal-Derived Hydrolysates and Antioxidant Activities

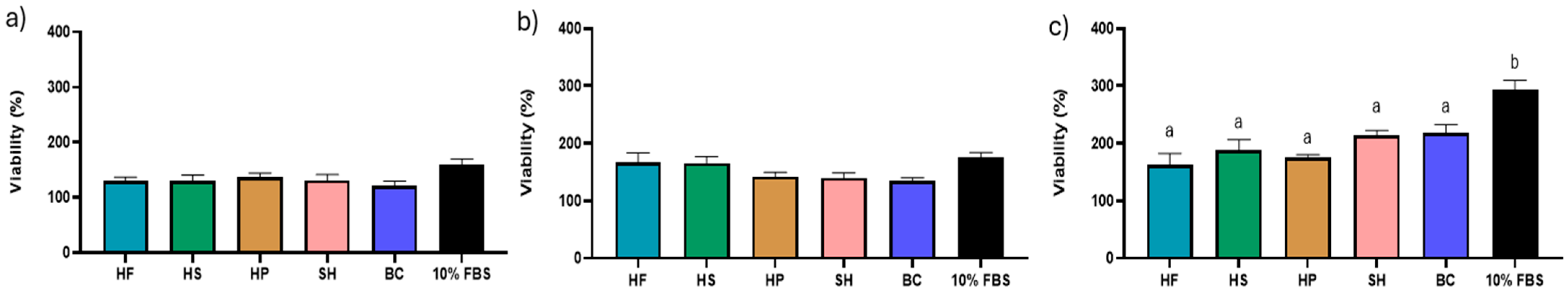

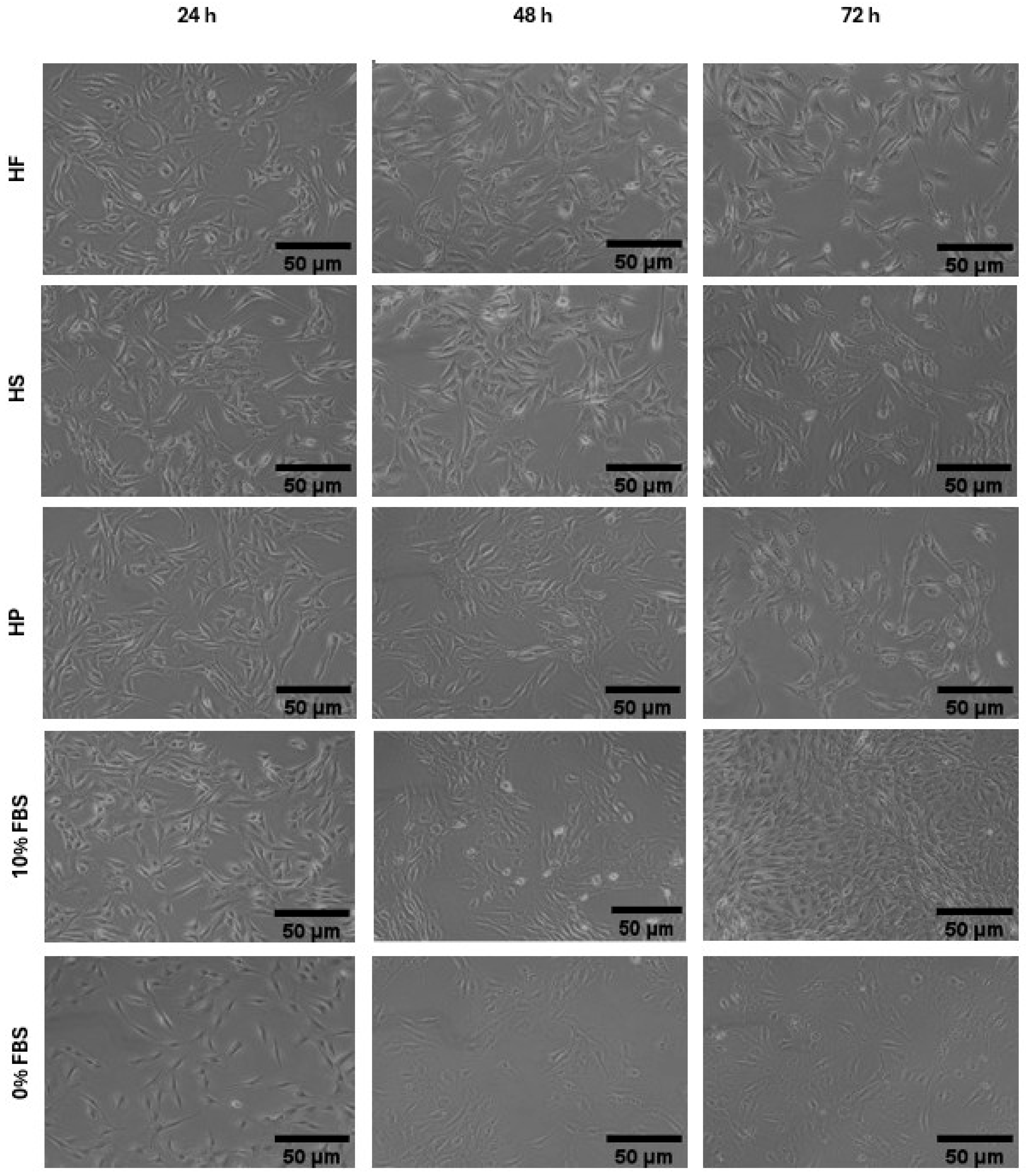

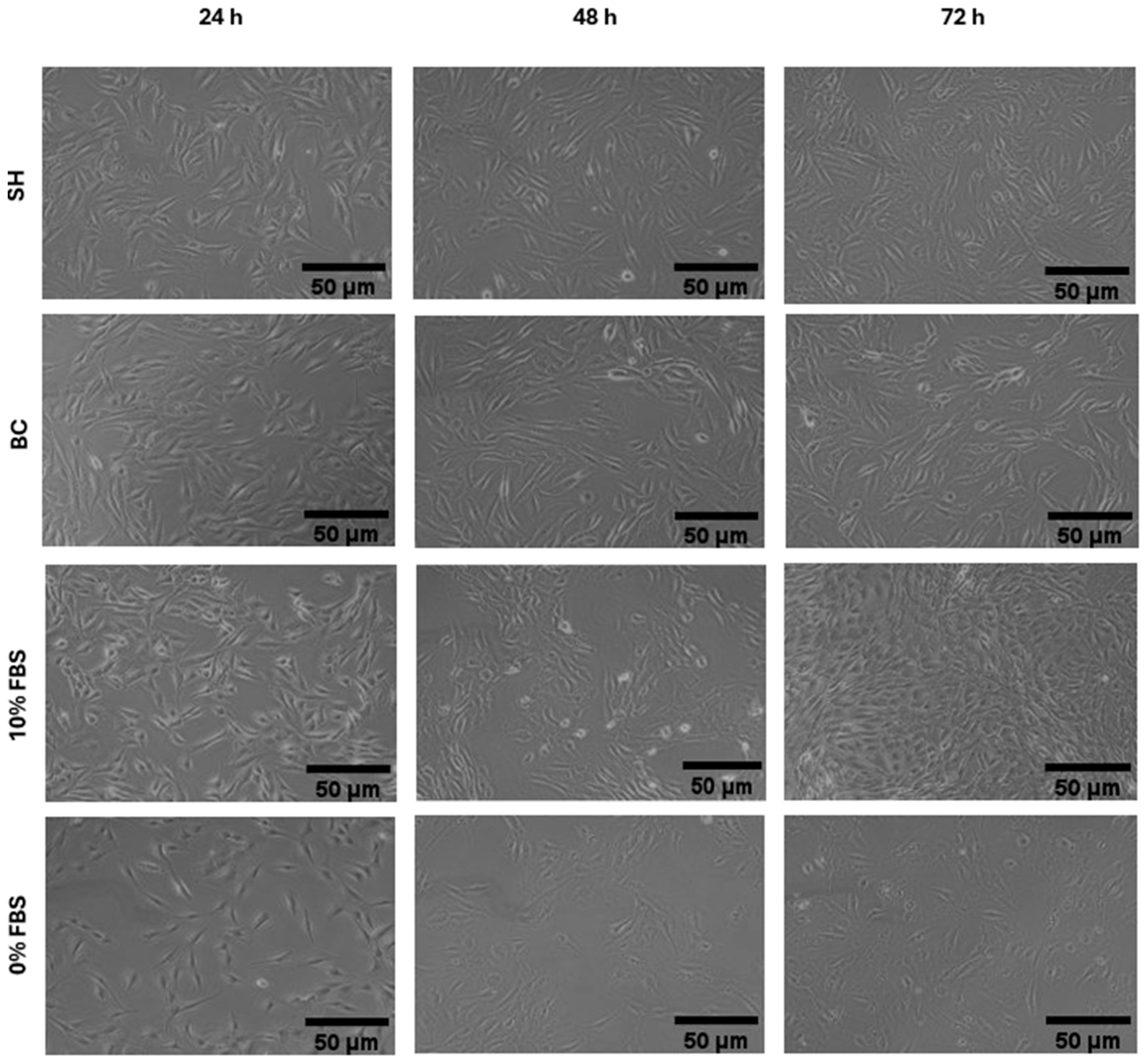

3.2. Effects of Hydrolysates on Cell Vitality and Morphology

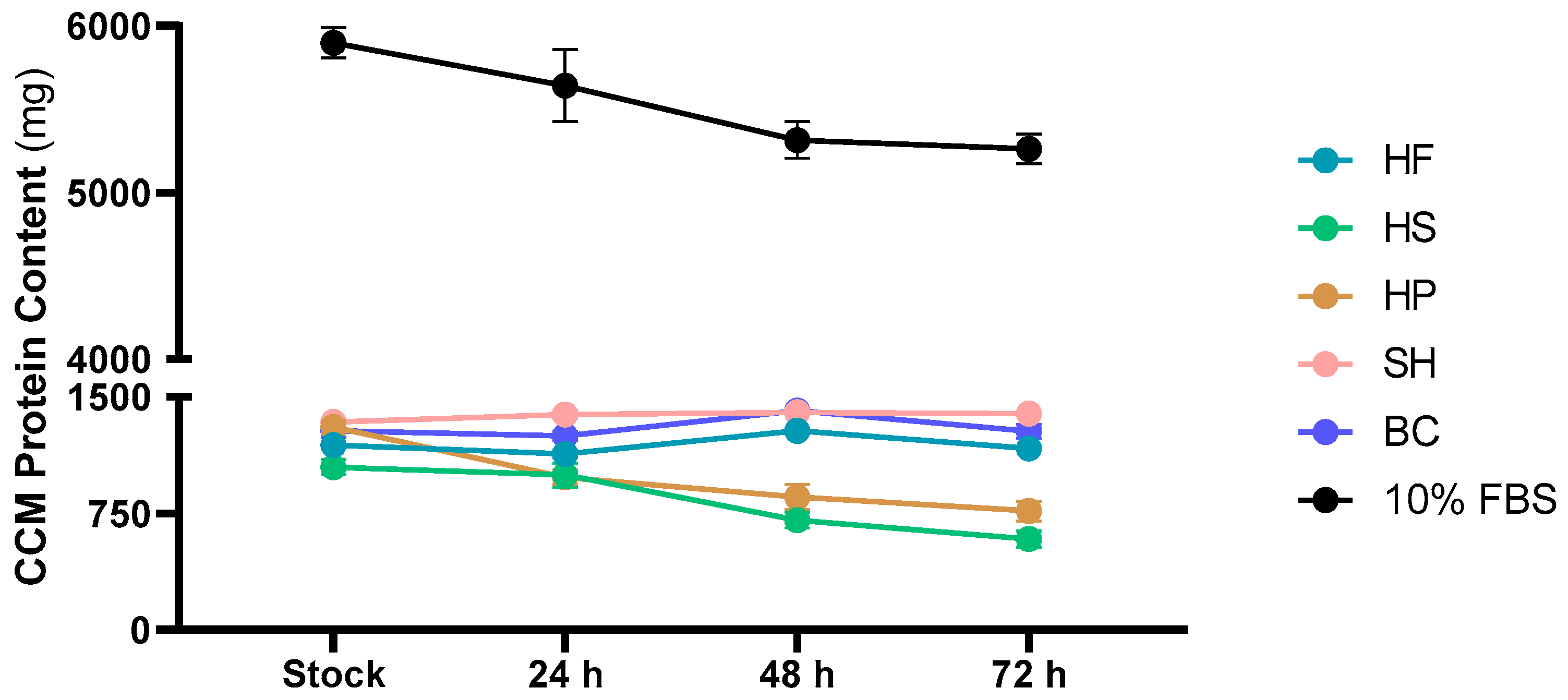

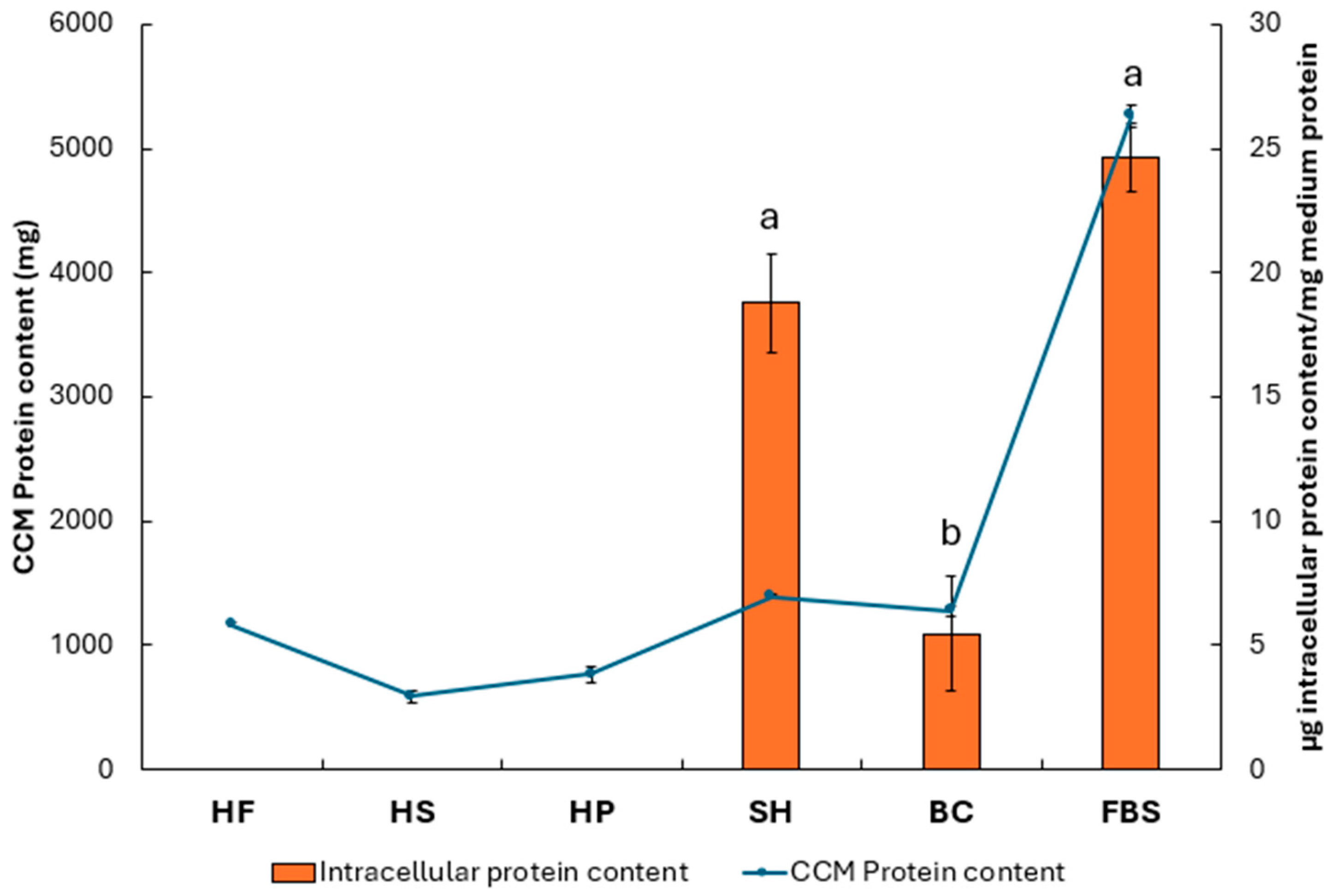

3.3. Evaluation of Protein Content in Cell Culture Media and in Cell Biomass

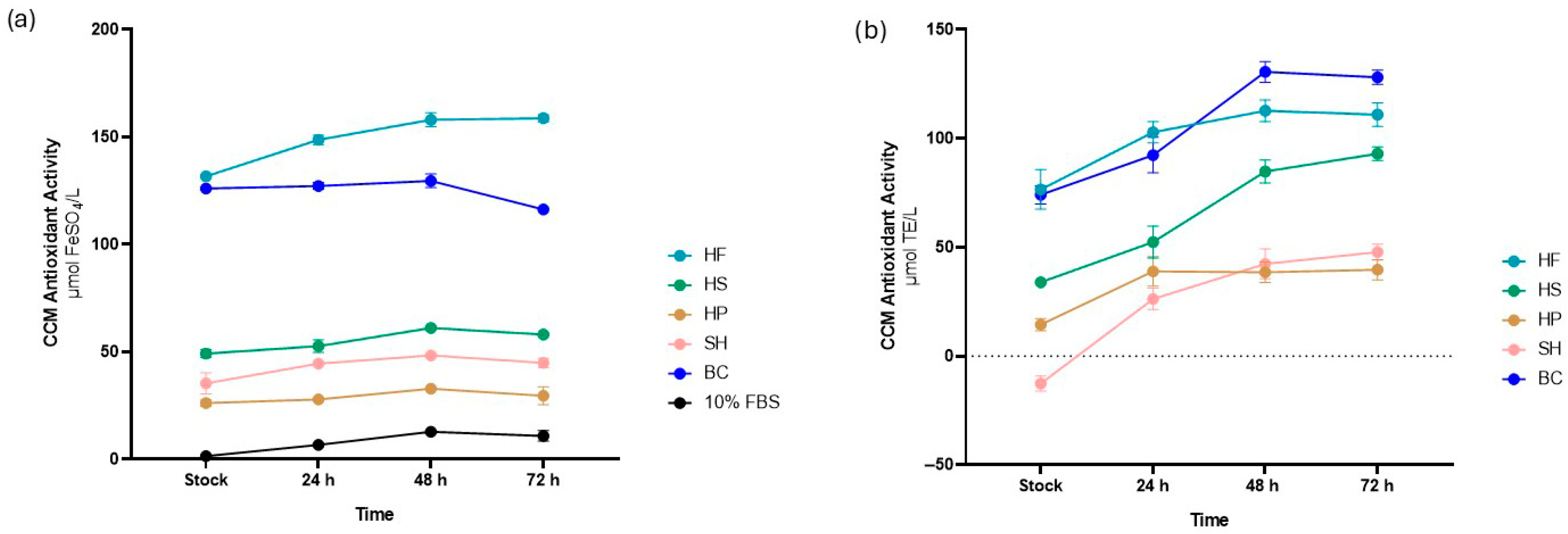

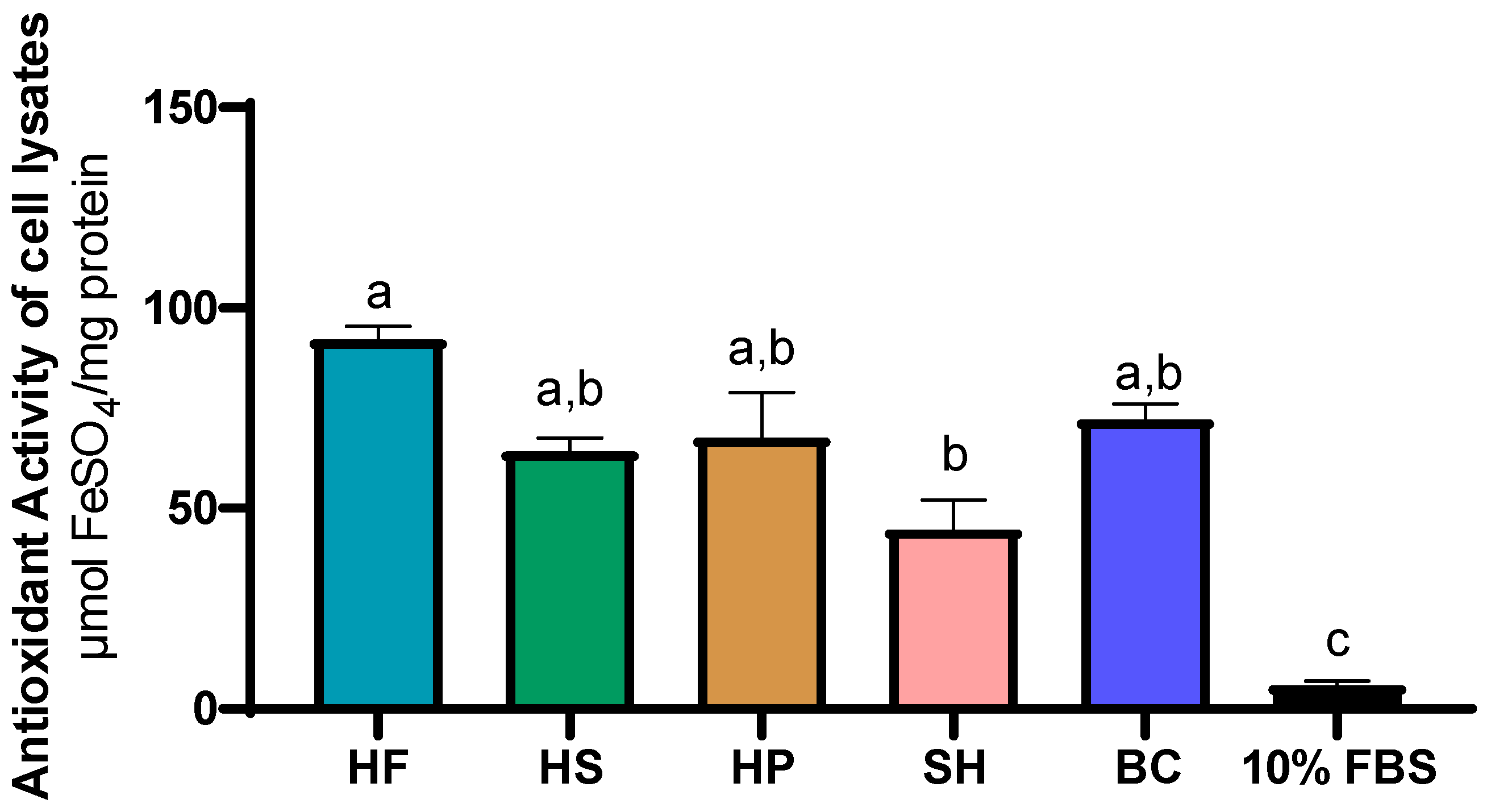

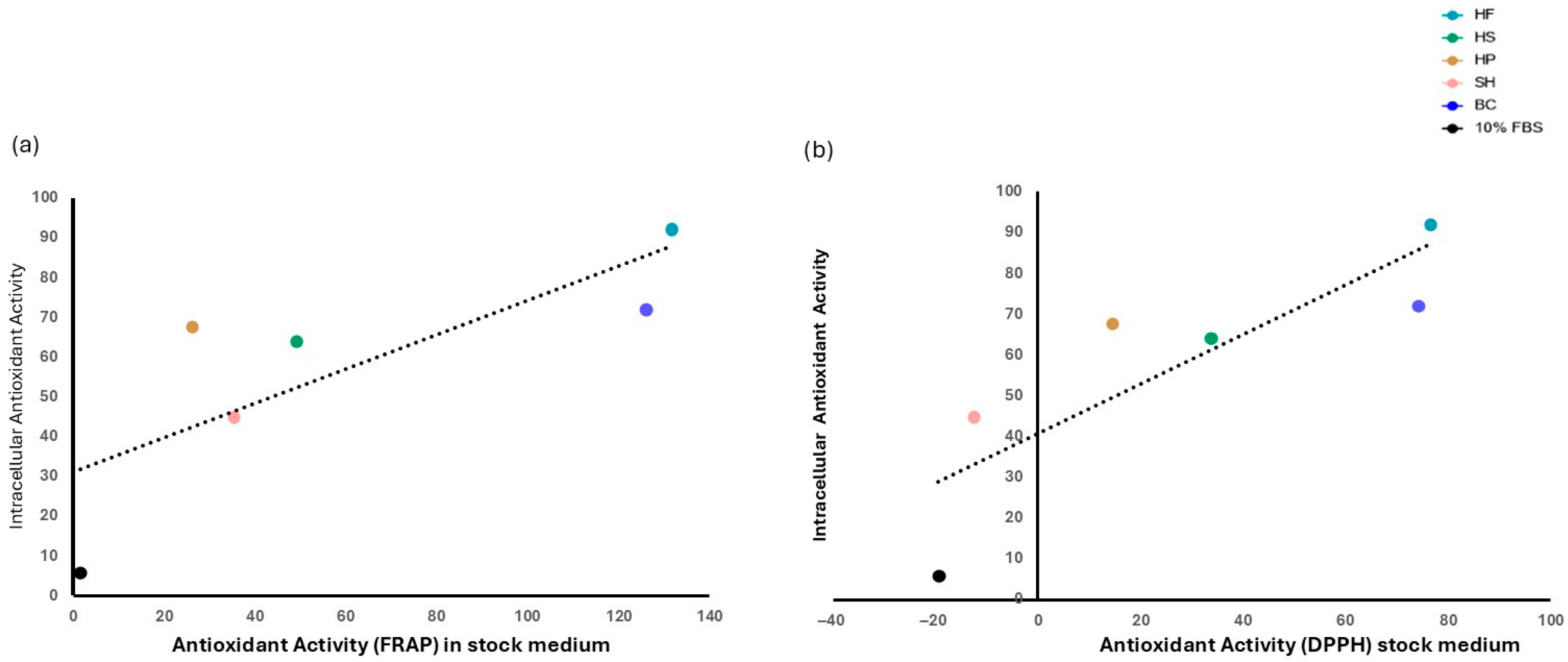

3.4. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity in Cell Culture Media and in Cell Biomass

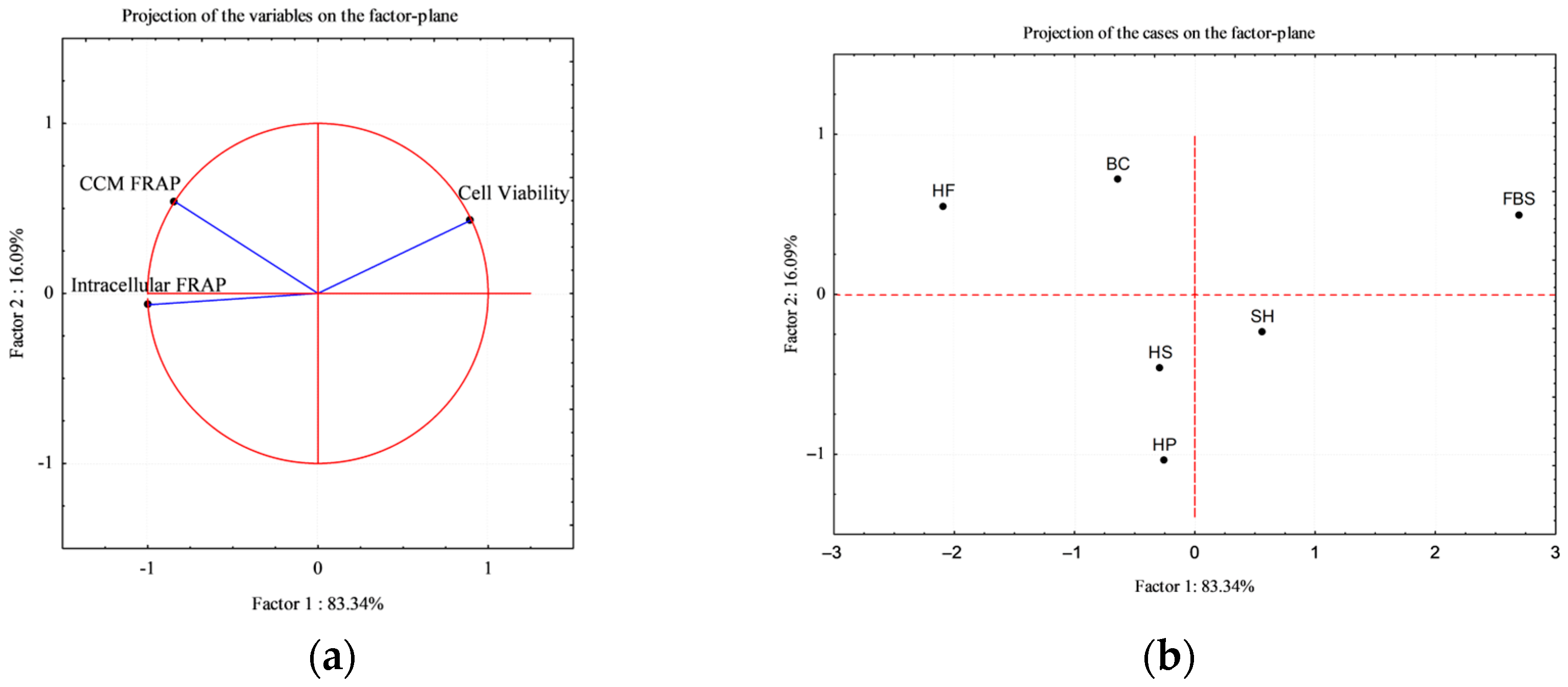

3.5. Multivariate Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Blue Crab |

| CM | Cultured Meat |

| CCM | Cell Culture Media |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| HF | Hemp Flower |

| HS | Hempseed |

| HP | Hempseed Protein |

| SH | Shrimp |

References

- Smith, D.J.; Helmy, M.; Lindley, N.D.; Selvarajoo, K. The transformation of our food system using cellular agriculture: What lies ahead and who will lead it? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.F.; Chriki, S.; Fournier, D.; Ellies-Oury, M.P. Will “cultured meat” transform our food system towards more sustainability? Animal 2025, 19, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treich, N. Cultured Meat: Promises and Challenges. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2021, 79, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, R.; Tago, D.; Treich, N. Infectious Diseases and Meat Production. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, A.J.; Rittenberg, M.L.; Shub, M.; Saad, M.K.; Mirliani, A.B.; Dolgin, J.; Kaplan, D.L. A Beefy-R culture medium: Replacing albumin with rapeseed protein isolates. Biomaterials 2023, 296, 122092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenzle, L.; Egger, K.; Spangl, B.; Hussein, M.; Ebrahimian, A.; Kuehnel, H.; Ferreira, F.C.; Marques, D.M.C.; Berchtold, B.; Borth, N.; et al. Low-cost food-grade alternatives for serum albumins in FBS-free cell culture media. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubalek, S.; Post, M.J.; Moutsatsou, P. Towards resource-efficient and cost-efficient cultured meat. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 47, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.Y.; Lu, H.K.; Lim, Z.F.S.; Lim, H.W.; Ho, Y.S.; Ng, S.K. Applications and analysis of hydrolysates in animal cell culture. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, T.S.; Giromini, C.; Rebucci, R.; Lanzoni, D.; Petrosillo, E.; Baldi, A.; Cheli, F. Milk whey as a sustainable alternative growth supplement to fetal bovine serum in muscle cell culture. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 4749–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.; Thorrez, L.; Hocquette, J.F.; Troy, D.; Gagaoua, M. “Cellular agriculture”: Current gaps between facts and claims regarding “cell-based meat”. Animal Front. 2023, 13, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomkamp, C.; Skaalure, S.C.; Fernando, G.F.; Ben-Arye, T.; Swartz, E.W.; Specht, E.A. Scaffolding Biomaterials for 3D Cultivated Meat: Prospects and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Valencak, T.G.; Tan, L.P.; Zhu, Y.; Shan, T. The future of cultured meat: Focusing on multidisciplinary, digitization, and nutritional customization. Food Res. Int. 2025, 219, 117005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, D.M.; Ülkü, M.A. Cellular agriculture and the circular economy. In Cellular Agriculture: Technology, Society, Sustainability and Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 393–405. ISBN 9780443187674. [Google Scholar]

- Batish, I.; Zarei, M.; Nitin, N.; Ovissipour, R. Evaluating the Potential of Marine Invertebrate and Insect Protein Hydrolysates to Reduce Fetal Bovine Serum in Cell Culture Media for Cultivated Fish Production. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tan, J.; Jiang, B.; Wu, D.; Yao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, Y. Serum-free media for cultured meat: Insights into protein hydrolysates as proliferation enhancers. Food Res. Int. 2025, 219, 117016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaibam, B.; Meira, C.S.; Nery, T.B.R.; Galland, F.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Goldbeck, R. Low-cost protein extracts and hydrolysates from plant-based agro-industrial waste: Inputs of interest for cultured meat. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 93, 103644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaibam, B.; da Silva, M.F.; de Mélo, A.H.F.; Carvalho, P.H.; Galland, F.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Goldbeck, R. Non-animal protein hydrolysates from agro-industrial wastes: A prospect of alternative inputs for cultured meat. Food Chem. 2024, 443, 138515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.D.; Ganguly, K.; Jeong, M.S.; Patel, D.K.; Patil, T.V.; Cho, S.J.; Lim, K.T. Bioengineered lab-grown meat-like constructs through 3D bioprinting of antioxidative protein hydrolysates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 34513–34526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Brief to The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136367-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mutalipassi, M.; Esposito, R.; Ruocco, N.; Viel, T.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Bioactive compounds of nutraceutical value from fishery and aquaculture discards. Foods 2021, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, C.M.; Manuguerra, S.; Arena, R.; Renda, G.; Ficano, G.; Randazzo, M.; Fricano, S.; Sadok, S.; Santulli, A. In Vitro Bioactivity of Astaxanthin and Peptides from Hydrolisates of Shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris) By-Products: From the Extraction Process to Biological Effect Evaluation, as Pilot Actions for the Strategy “From Waste to Profit”. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggink, K.M.; Gonçalves, R.; Skov, P.V. Shrimp Processing Waste in Aquaculture Feed: Nutritional Value, Applications, Challenges, and Prospects. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinon, B.; Molinari, R.; Costantini, L.; Merendino, N. The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional quality and potential functionality for human health and nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzoni, D.; Skřivanová, E.; Rebucci, R.; Crotti, A.; Baldi, A.; Marchetti, L.; Giromini, C. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of In Vitro Digested Hemp-Based Products. Foods 2023, 12, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzoni, D.; Mercogliano, F.; Rebucci, R.; Bani, C.; Pinotti, L.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Savoini, G.; Baldi, A.; Giromini, C. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of hemp co-products following green chemical extraction and ex vivo digestion. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, A.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Ling, S.; Wu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chen, H.; Lai, Y.; et al. Growing meat on autoclaved vegetables with biomimetic stiffness and micro-patterns. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, R.; Manuguerra, S.; Gonzalez, M.M.; Petrosillo, E.; Lanzoni, D.; Poulain, C.; Debeaufort, F.; Giromini, C.; Francesca, N.; Messina, C.M.; et al. Valorization of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) By-Products into Antioxidant Protein Hydrolysates for Nutraceutical Applications. Animals 2025, 15, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Liang, K.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Lai, F. Identification and characterization of two novel α-glucosidase inhibitory oligopeptides from hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed protein. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 26, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Donnay-Moreno, C.; Barnathan, G.; Jaouen, P.; Bergé, J.P. Improvement of lipid and phospholipid recoveries from sardine (Sardina pilchardus) viscera using industrial proteases. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 2327–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaleem, M.A.; Elbassiony, K.R.A. Evaluation of phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of gamma irradiated quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Brazilian J. Biol. 2021, 81, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Liang, S.; Luu, Q.M.; Kempson, I. The MTT assay: A method for error minimization and interpretation in measuring cytotoxicity and estimating cell viability. In Cell Viability Assays: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, J.M. Procedure: Preparation of DPPH Radical, and antioxidant scavenging assay. DPPH Microplate Protoc. 2012, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Subbiahanadar Chelladurai, K.; Selvan Christyraj, J.D.; Rajagopalan, K.; Yesudhason, B.V.; Venkatachalam, S.; Mohan, M.; Chellathurai Vasantha, N.; Selvan Christyraj, J.R.S. Alternative to FBS in animal cell culture—An overview and future perspective. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibani, M.E.; Heidari, B.; Khodabandeh, S.; Shahangian, S.; Mirdamadi, S.; Mirzaei, M. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of protein hydrolysate from rocky shore crab, grapsus albolineathus, as affected by progress of hydrolysis. Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2020, 8, 184–193. Available online: https://ij-aquaticbiology.com/index.php/ijab/article/view/639 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Camargo, T.R.; Mantoan, P.; Ramos, P.; Monserrat, J.M.; Prentice, C.; Fernandes, C.C.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Valenti, W.C. Bioactivity of the Protein Hydrolysates Obtained from the Most Abundant Crustacean Bycatch. Mar. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Cruz, M.V.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Vioque, J.; Girón-Calle, J.; Quevedo-Corona, L. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Rivero-Pino, F.; Villanueva, A.; Toscano-Sanchez, R.; Martin, M.E.; Millan, F.; Millan-Linares, M.C. Nutritional composition, ultrastructural characterization, and peptidome profile of antioxidant hemp protein hydrolysates. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoki, M.C.; de Mello, A.F.M.; Martinez-Burgos, W.J.; da Silva Vale, A.; Biagini, G.; Piazenski, I.N.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. Scaling-Up of Cultivated Meat Production Process. In Cultivated Meat: Technologies, Commercialization and Challenges; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 241–264. ISBN 9783031559686. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, G.; Hanigan, M.D.; Cantalapiedra-Hijar, G.; Li, M. Branched-chain amino acids in muscle growth: Mechanisms, physiological functions, and applications. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Amino acids regulating skeletal muscle metabolism: Mechanisms of action, physical training dosage recommendations and adverse effects. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, G.; Storz, M.A.; Calapai, G. The role of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) as a functional food in vegetarian nutrition. Foods 2023, 12, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, V.; Pastorelli, G.; Tedesco, D.E.A.; Turin, L.; Guerrini, A. Alternative protein sources in aquafeed: Current scenario and future perspectives. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Fang, Z. Hempseed in food industry: Nutritional value, health benefits, and industrial applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, T.; Zheng, S.; Wu, G. Nutrition and Functions of Amino Acids in Aquatic Crustaceans. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1285, pp. 169–198. ISBN 978-3-030-54462-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.Y.; Yun, S.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.W.; Choi, J.S.; Hur, S.J. Review of the current research on fetal bovine serum and the development of cultured meat. Food Sci. Anim. Res. 2022, 42, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G.P.V. Cell cycle: Regulatory events in G1 → S transition of mammalian cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 1994, 54, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ma, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Sun, B.; Shi, Y.; Cao, X. Rosmarinic acid inhibits platelet aggregation and neointimal hyperplasia in vivo and vascular smooth muscle cell dedifferentiation, proliferation, and migration in vitro via activation of the keap1-Nrf2-ARE antioxidant system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 7420–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, L.; Cakebread, J.A.; Loveday, S.M. Food proteins from animals and plants: Differences in the nutritional and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L. Interactions of polyphenols with carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, T.; Malakpour-Permlid, A.; Chary, A.; D’Alessandro, V.; Haut, L.; Seufert, S.; Wenzel, E.V.; Hickman, J.; Bieback, K.; Wiest, J.; et al. Fetal bovine serum: How to leave it behind in the pursuit of more reliable science. Front. Toxicol. 2025, 7, 1612903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hällbrink, M.; Oehlke, J.; Papsdorf, G.; Bienert, M. Uptake of cell-penetrating peptides is dependent on peptide-to-cell ratio rather than on peptide concentration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2004, 1667, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruseska, I.; Zimmer, A. Internalization mechanisms of cell-penetrating peptides. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Sheng, K.; Xiang, N.; Zhang, X. Cell culture medium cycling in cultured meat: Key factors and potential strategies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, S.; Palanisamy, M.; Mathys, A.; Heinz, V. Sustainability of insect use for feed and food: Life Cycle Assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A. Insects as food and feed, a new emerging agricultural sector: A review. J. Insects Food Feed. 2020, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grune, T. Breakdown of oxidized proteins as a part of secondary antioxidant defenses in mammalian cells. BioFactors 1997, 6, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leist, M.; Raab, B.; Maurer, S.; Rösick, U.; Brigelius-Flohé, R. Conventional cell culture media do not adequately supply cells with antioxidants and thus facilitate peroxide-induced genotoxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinska, A.; Wnuk, M.; Slota, E.; Bartosz, G. Total anti-oxidant capacity of cell culture media. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007, 34, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Wang, X.S.; Yang, X.Q. Enzymatic hydrolysis of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) protein isolate by various proteases and antioxidant properties of the resulting hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, R.; Renda, G.; Ottaviani Aalmo, G.; Debeaufort, F.; Messina, C.M.; Santulli, A. Valorization of the Invasive Blue Crabs (Callinectes sapidus) in the Mediterranean: Nutritional Value, Bioactive Compounds and Sustainable By-Products Utilization. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, E. The Blue Treasure: Comprehensive Biorefinery of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus). Foods 2024, 13, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, D.; Lauritano, C.; Palma Esposito, F.; Riccio, G.; Rizzo, C.; de Pascale, D. Fish waste: From problem to valuable resource. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Ghany, M.N.; Hamdi, S.A.; Elbaz, R.M.; Aloufi, A.S.; El Sayed, R.R.; Ghonaim, G.M.; Farahat, M.G. Development of a Microbial-Assisted Process for Enhanced Astaxanthin Recovery from Crab Exoskeleton Waste. Fermentation 2023, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastolo, A.; Calabrò, S.; Cutrignelli, M.I. A review on the use of agro-industrial CO-products in animals’ diets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Rohani, A.; Zarei, M.; Kulkarni, A.; Batarseh, F.A.; Blackstone, N.T.; Ovissipour, R. Toward sustainable culture media: Using artificial intelligence to optimize reduced-serum formulations for cultivated meat. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Shimizu, T. A circular cell culture system using microalgae and mammalian myoblasts for the production of sustainable cultured meat. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, P.Y.; Suntornnond, R.; Choudhury, D. The nutritional paradigm of cultivated meat: Bridging science and sustainability. Trend Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate | T°C | pH | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 60 | 8.5 | 120 |

| HS | 60 | 8.5 | 120 |

| HP | 60 | 8.5 | 120 |

| SH | 60 | 8.5 | 150 |

| BC | 53 | 9 | 265 |

| Samples | DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity (IC 50 mg/mL of Extract) | Reducing Power (EC 50 mg/mL of Extract) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | 7.92 ± 1.01 | 30.56 ± 1.77 |

| HS | 9.71 ± 1.52 | 37.44 ± 2.17 |

| HP | 10.67 ± 1.34 | 41.14 ± 2.38 |

| SH | 50.98 ± 3.85 | 116.04 ± 12.44 |

| BC | 11.39 ± 1.63 | 61.92 ± 7.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lanzoni, D.; Manuguerra, S.; Arena, R.; Santulli, A.; Marchetti, L.; Messina, C.M.; Giromini, C. Valorization of Hemp, Shrimp and Blue Crab Co-Products as Novel Culture Media Ingredients to Improve Protein Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Cultured Meat in Cell-Based Food Applications. Foods 2026, 15, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020352

Lanzoni D, Manuguerra S, Arena R, Santulli A, Marchetti L, Messina CM, Giromini C. Valorization of Hemp, Shrimp and Blue Crab Co-Products as Novel Culture Media Ingredients to Improve Protein Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Cultured Meat in Cell-Based Food Applications. Foods. 2026; 15(2):352. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020352

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanzoni, Davide, Simona Manuguerra, Rosaria Arena, Andrea Santulli, Luca Marchetti, Concetta Maria Messina, and Carlotta Giromini. 2026. "Valorization of Hemp, Shrimp and Blue Crab Co-Products as Novel Culture Media Ingredients to Improve Protein Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Cultured Meat in Cell-Based Food Applications" Foods 15, no. 2: 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020352

APA StyleLanzoni, D., Manuguerra, S., Arena, R., Santulli, A., Marchetti, L., Messina, C. M., & Giromini, C. (2026). Valorization of Hemp, Shrimp and Blue Crab Co-Products as Novel Culture Media Ingredients to Improve Protein Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Cultured Meat in Cell-Based Food Applications. Foods, 15(2), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020352