Recent Advances on Queen Bee Larvae: Sources, Chemical Composition, and Health-Benefit Bioactivities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

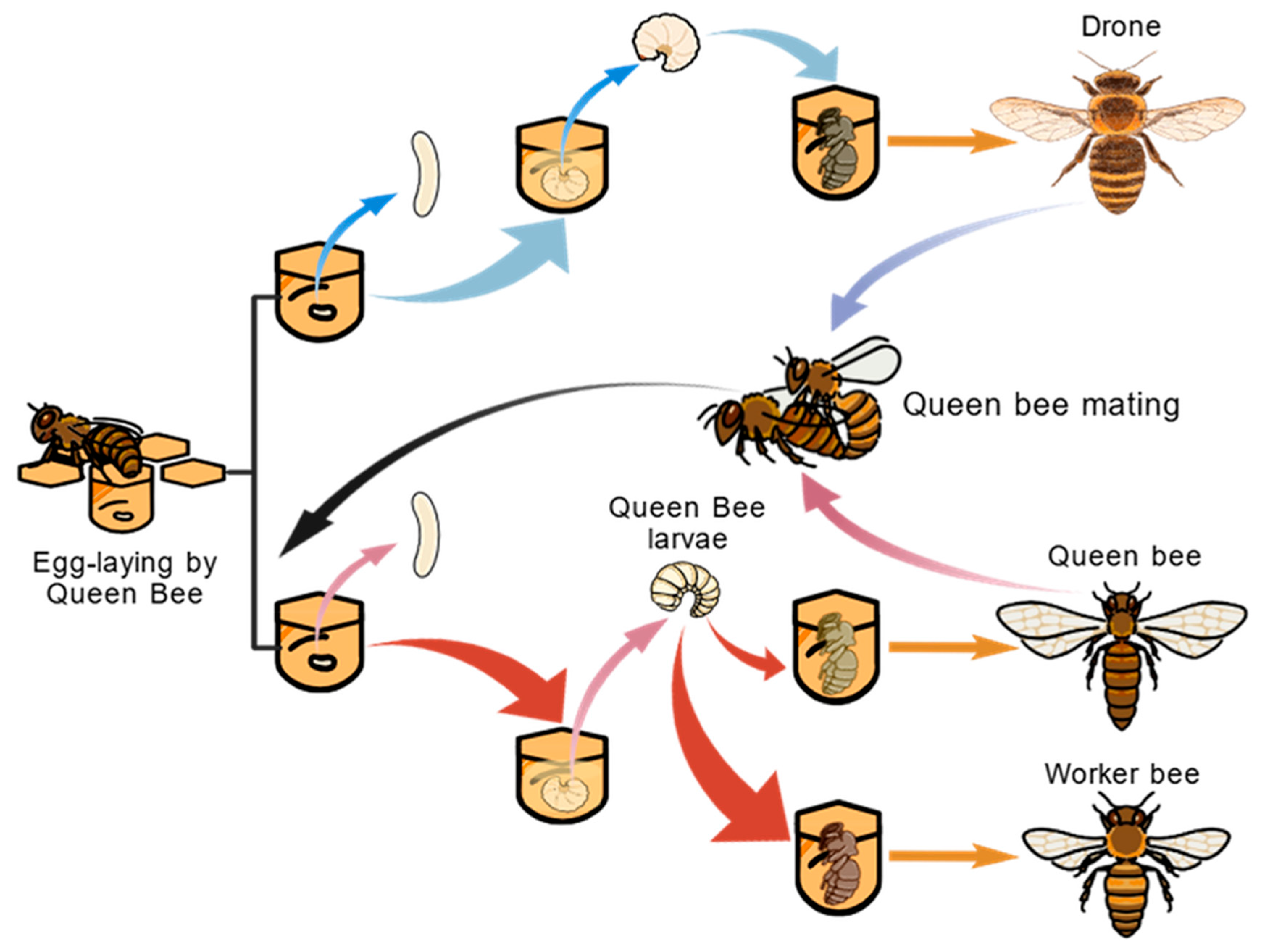

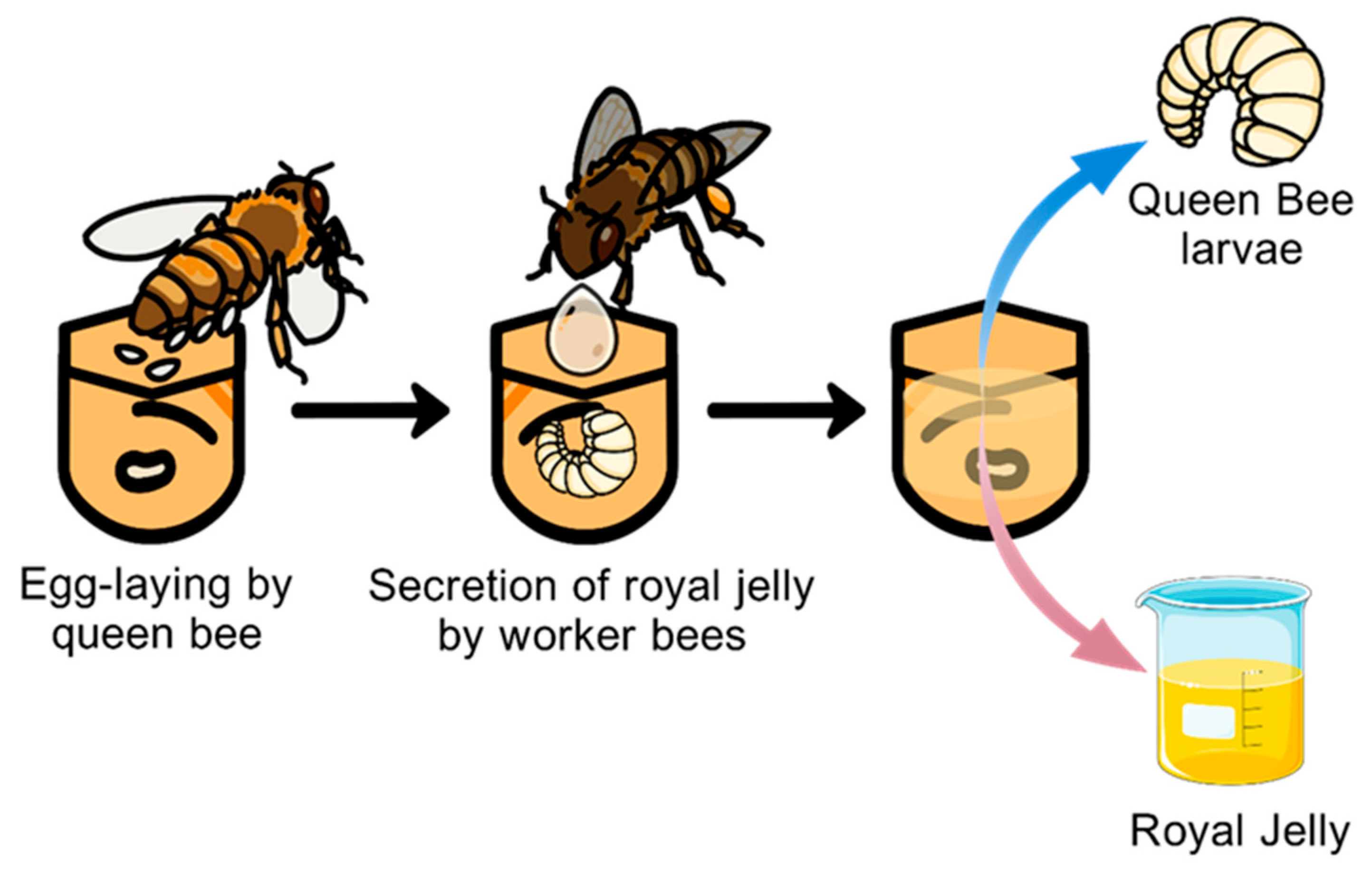

3. Sources of QBL

4. Chemical Composition of QBL

4.1. Proteins

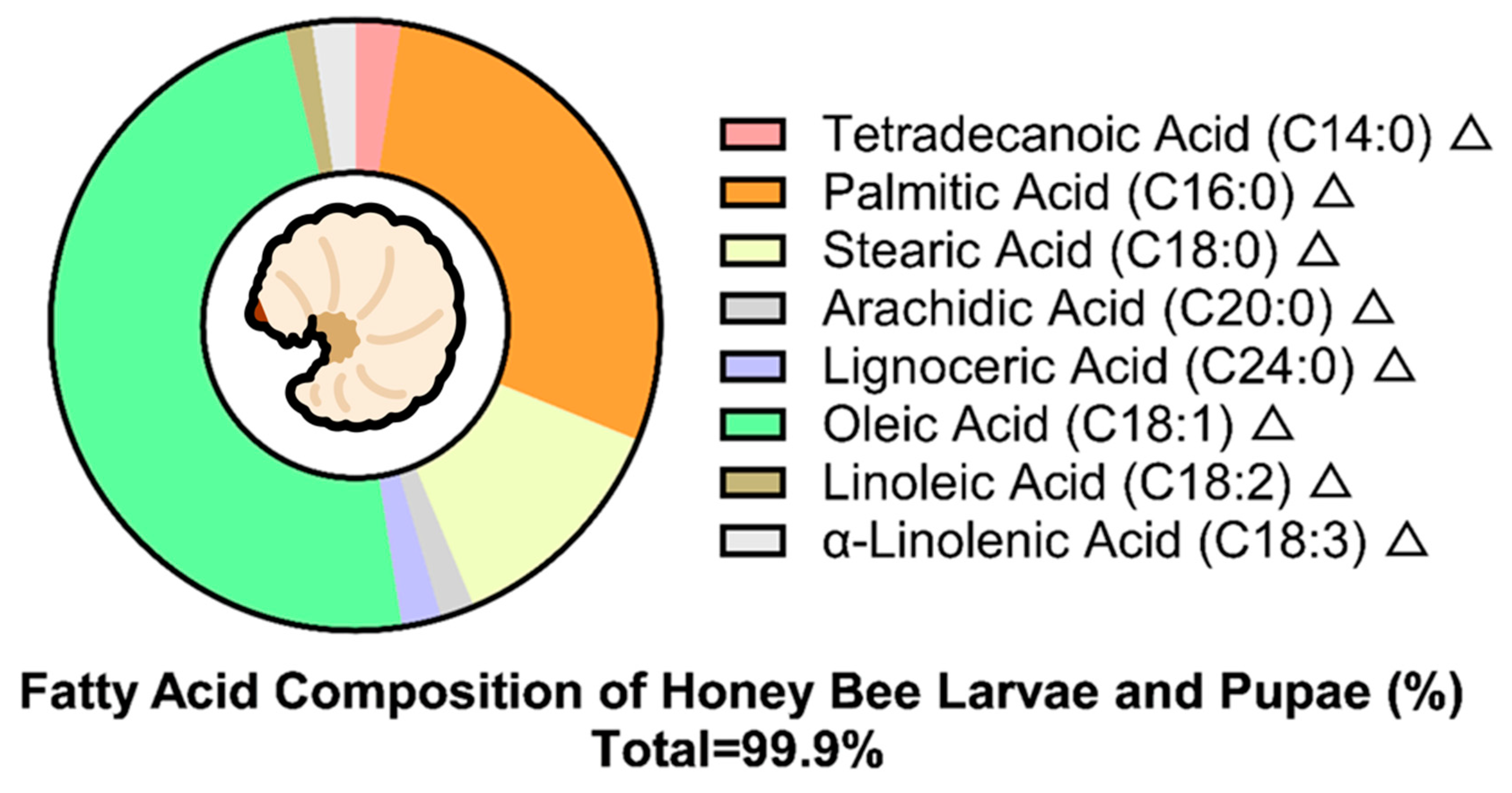

4.2. Lipids

4.3. Carbohydrates

4.4. Other Components

5. Health Benefit Effects of QBL

5.1. Anti-Aging Effects

5.2. Antioxidant Effects

5.3. Metabolic Regulation Effects

5.4. Other Bioactivities

6. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henchion, M.; Hayes, M.; Mullen, A.M.; Fenelon, M.; Tiwari, B. Future Protein Supply and Demand: Strategies and Factors Influencing a Sustainable Equilibrium. Foods 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Egas-Montenegro, E. Edible Insects: A Food Alternative for the Sustainable Development of the Planet. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mao, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Fang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; et al. Edible Insects: A New Sustainable Nutritional Resource Worth Promoting. Foods 2023, 12, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhumury, H.C.D. Edible Insects: Alternative Protein for Sustainable Food and Nutritional Security. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 883, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza-Vilela, J.; Andrew, N.R.; Ruhnke, I. Insect Protein in Animal Nutrition. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2019, 59, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Lakemond, C.M.; Sagis, L.M.; Eisner-Schadler, V.; van Huis, A.; van Boekel, M.A. Extraction and Characterisation of Protein Fractions from Five Insect Species. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, C.L.; Jian, Y.X.; Shang, R.S.; Zhang, J.B.; Zheng, L.Y. Development, application, and industrial prospects of insect protein. Chem. Bioeng. 2024, 41, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuse, E.R.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Yusuf, A.A.; Machekano, H.; Egonyu, J.P.; Kimathi, E.; Mohamed, S.F.; Kassie, M.; Subramanian, S.; Onditi, J.; et al. The Global Atlas of Edible Insects: Analysis of Diversity and Commonality Contributing to Food Systems and Sustainability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Costa, C.A. Bee Brood as a Food for Human Consumption: An Integrative Review of Phytochemical and Nutritional Composition. Insects 2025, 16, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Zhao, M.; He, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Ding, W.F. Edible Insects in China: Utilization and Prospects. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, X.; Pokharel, S.S.; Qian, L.; Chen, F. Research Progress and Production Status of Edible Insects as Food in China. Foods 2024, 13, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Shi, T.; Cao, H.; Chen, G.; Yu, L. Potential of Queen Bee Larvae as a Dietary Supplement for Obesity Management: Modulating the Gut Microbiota and Promoting Liver Lipid Metabolism. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 3848–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampat, G.; Benno, M.R.V.; Chuleui, J. Honey Bees and their Brood: A Potentially Valuable Resource of Food, Worthy of Greater Appreciation and Scientific Attention. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 45, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Insects as food in China. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1997, 36, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z. Common edible insects and their utilization in China. Entomol. Res. 2009, 39, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.L.; Katarína, B.; Hervé, C.; Gaëlle, D.; Foued, S.E.; Mao, F.; Cui, G.; Bin, H.; Tatiana, K.K.; Ke, L.J.; et al. Standard Methods for Apis mellifera Royal Jelly Research. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.Q.; Yang, H.B.; Chen, J.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.P.; Kong, M. Analysis of Nutrition Composition on Queenbee Larvae. Available online: https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=MdENDFpkZq5pSulFIe_77C__oj2NHPlHy5jGiMkHu0uf0foaTY4ad84mwG8h1A-Tj9-w16KU2CHcFfJ2OVNzDczDQp6LtrLXQSWGoQ8yWIVKAANNJI67RV6or-i_HsEpfBW8tu3ygNFij0RZRcgn6PB03OadGP83VbF65Xfs9TJkEzT_bsMkfxw3BS9zgovW&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Bruun, J.A.; Josh, E.; Adi, J.L.; Ofir, B.; Itzhak, M.; Bjørn, D.; Nanna, R.; Antoine, L.; Kirsten, F. Standard Methods for Apis mellifera Brood as Human Food. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onore, G. A Brief Note on Edible Insects in Ecuador. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1997, 36, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J.; Moreno, J.M.P.; Prado, E.E.; Perez, M.A.; Otero, J.L.; Larron De Guevara, O. Nutritional Value of Edible Insects from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1997, 10, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, J.-A.; Peng, C.-C.; Hsu, P.-S.; Wu, T.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wu, M.-C. Effects of Physical Sterilization on Microbial Safety, Nutritional Composition, and Antioxidant Activity of Queen Bee Larva Powder, a By-Product of Royal Jelly Production. Food Control 2024, 165, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Dong, M.; Liu, K.; Lu, Y.; Yu, B. Antioxidant Activity of Queen Bee Larvae Processed by Enzymatic Hydrolysis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuraphan, P.; Suang, S.; Bunrod, A.; Kanjanakawinkul, W.; Chaiyana, W. Potential of Bioactive Protein and Protein Hydrolysate from Apis mellifera Larvae as Cosmeceutical Active Ingredients for Anti-Skin Aging. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, L.; Fan, F.; Yang, Y.; Xue, X. Supplementation with Queen Bee Larva Powder Extended the Longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Xue, X.; Liu, P.; Hu, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L. Queen Bee Larva, an Edible By-Product of Royal Jelly, Alleviate D-Galactose-Induced Aging in Mouse by Regulating Gut Microbiota Structure and Amino Acid Metabolism. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamakura, M. Royalactin induces queen differentiation in honeybees. Nature 2011, 473, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, Z.; Correia, B.A.; Souza, V.J.C.; Pereira, B.C.; Magalhaes, P.P.d.; Silva, F.M.d.; Souza, B.T.d.; Oliveira, O.R.d. Modification of the head proteome of nurse honeybees (Apis mellifera) exposed to field-relevant doses of pesticides. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2190. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, N.; Hulbert, A.J.; Brenner, G.C.; Brown, S.H.J.; Mitchell, T.W.; Else, P.L. Honey Bee Caste Lipidomics in Relation to Life-History Stage and the Long Life of the Queen. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb207043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Correia, P.M.R.; Anjos, O.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C.A. Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) Broods: Composition, Technology and Gastronomic Applicability. Foods 2022, 11, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, M.; Mishyna, M.; Itzhak Martinez, J.J.; Benjamin, O. Edible Larvae and Pupae of Honey Bee (Apis mellifera): Odor and Nutritional Characterization as a Function of Diet. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishyna, M.; Martinez, J.-J.I.; Chen, J.; Benjamin, O. Extraction, Characterization and Functional Properties of Soluble Proteins from Edible Grasshopper (Schistocerca gregaria) and Honey Bee (Apis mellifera). Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.C.; Yuan, C.Y.; Ding, G.L. Research Progress on the Factors Influencing the Quality and Performance of Honey Bee Queens. J. Environ. Entomol. 2023, 45, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-F. The Life Patterns of Bees. Available online: https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=W694F5cljyADAa1xITlvHQNiuS7IfQ65qBY-SNbdyAxaj4MWwQ2ti0TC5wUC-1dpRO34Gp9GW2i302FUgtlrYTIQPhE1j9J48AvFQ3R0WPmiKrTSsfpKREZemKHN1kOplxd60mcsCL5Eumd2D7cgJuN1qu0h0wuq-9s_08hxvg2t0iG08LIiKnpMfALEfMJj&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yan, L.L.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.L.; Xiang, G.W.; Ren, Q.; Luo, W.H. Research Advances in Honeybee Drones. Available online: https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=W694F5cljyCeNhOeBNn2FSwWx2jV2NRqPJ8kHQi2BGoPrm7Ch0n-tIBEvVb654SHY0QaCimihTmx3aPkoLzF2lAPtYVZr0wjJ61IjCkNvXZFdhBemklLwCJirSvMWXnz8EN19P9gkG82EuVcfbs1q9fH-KM2cIRG89RIzsxPWVjjmxl43IoW5Nh-knw2PjbAW5kDjyC1AEg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Grishina, Z.; Gengin, M. Changes in Peptide and Protein Concentrations during the Ontogenesis of Honeybee (A. mellifera) Drone Larvae Is Associated to Variations in Protease Activity. Biotecnol. Apl. 2016, 33, 4221–4224. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.-I. Growth Rates of Young Queen and Worker Honeybee Larvae. J. Apic. Res. 2015, 4, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.B.; Wu, D.Q.; Lin, Z.G.; Ji, T. Review on Biological Function of Royal Jelly. Chin. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2021, 52, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.F.; Zeng, Z.J.; Yan, W.Y.; Wu, X.B. Effects of Three Esters in Larval Pheromone on Nursing and Capping Behaviors of Workers and Queen Development in Apis cerana cerana and Apis mellifera ligustica. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2010, 53, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, J.; Begna, R.D.; Song, F.; Zheng, A.; Fang, Y. Differential protein expression in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) larvae: Underlying caste differentiation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Cilia, G.; Mancini, S.; Felicioli, A. Royal Jelly: An Ancient Remedy with Remarkable Antibacterial Properties. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanelis, D.; Liolios, V.; Rodopoulou, M.A.; Papadopoulou, F.; Tananaki, C. The Impact of Grafted Larvae and Collection Day on Royal Jelly’s Production and Quality. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.H.; Wang, Q.Q.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Huang, Y.; Feng, Y.X.; Feng, S.Y. Application Status of Royal Jelly in the Medical Field. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 133, 107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, E. Royal Jelly in Modern Biomedicine: A Review of Its Bioactive Constituents and Health Benefits. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 134, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.A.; Bakier, S.; Stocki, M. GC-MS Investigation of the Chemical Composition of Honeybee Drone and Queen Larvae Homogenate. J. Apic. Sci. 2016, 60, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qi, L.K.; Lin, L.; Li, J.; Li, X.M.; Kuang, Y.Z. Determination of Amino Acids in the Frozen Dry Powder of Queen Bee Larva by Precolumn Derivatization Coupled with Reversed-Phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3542.TS.20171117.1125.042 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Janssen, R.H.; Vincken, J.P.; van den Broek, L.A.M.; Fogliano, V.; Lakemond, C.M.M. Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factors for Three Edible Insects: Tenebrio molitor, Alphitobius diaperinus, and Hermetia illucens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 2275–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Kuang, Y.Z.; Deng, Y.Z. Comparative Analysis of Frozen Powder of Queen Bee Royal Jelly and Frozen Dry Powder of Queen Bee Larvae. Mod. Food 2016, 67, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.W.; Zhou, R.H. Biological Utilization Rate and Nutritional Efficacy of Dried Royal Jelly Larvae Powder Protein. Available online: https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=ufuULlVWCsMGYYZMmmX19YamBv7_l9N9BiEakaaMSqxfMlCB4sNIeSGAFnBLkagWLiy4-60Fdsy5mCqh0D-WTzHSkmfQCBwu_laWwUj4XtY1wMQQ_Nbe8MiaFRmNDOFhPezO90ngT_WMFKvJ0t8wzFAH8sCnxjxyDBaD1zwKwps8zBgvcWKuHSiyu7nGyNBX&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Zhu, H.B. A Study on the Preparation of Compound Bee Larva Tablet and Its Anti-Fatigue Effect. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Gao, Y. Isolation and Characterization of Proteins and Lipids from Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Queen Larvae and Royal Jelly. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.L.; Hu, F.L.; Ying, H.Z.; Yan, J.W.; Wang, D.J. Effects of Worker Bee Larvae and Pupae on SOD Activity and MDA Content in Rat Brain, Liver, and Blood. J. Zhejiang Chin. Med. Univ. 1997, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emine, S.; Meral, K.; Huseyin, S.; Arif, B.; Sengul, A.K. An Evaluation of the Chemical Composition and Biological Properties of Anatolian Royal Jelly, Drone Brood and Queen Bee Larvae. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, P.; Xu, S.H.; Zhu, J. Determination of DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Ability of Homemade Queen Bee Larva Cream with Whitening, Anti-aging and Anti Wrinkle Functions by the DPPH· Assay. Guangdong Chem. Ind. 2019, 46, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B. The Hydrolysate Component Analysis and Activity Evaluation of Queen Bee Larva. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.W.; Zhu, S.S.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.B. Experimental Study on Anti-Aging and Anti-Stress Abilities of Queen Bee Larva Powder. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2002, 24, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W. Effects of Dietary Queen Bee Larva Lyophilized Powder on Performance and Cholesterol of Laying Hens. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Xiong, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Z.; Liao, S.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, W.; Guo, J. Queen Bee Larva Consumption Improves Sleep Disorder and Regulates Gut Microbiota in Mice with PCPA-Induced Insomnia. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.L.; Chen, S.L.; Lin, X.Z.; Su, S.K.; Chen, M.L.; Ying, H.Z. Effects of Bee Larvae and Pupae on Anti-Stress Capacity in Mice. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkHHeoQLHKFFfW1OlLl0A0m0_pB_dan4D9Rusp3d5BDYiOYykPZnIII8uW0l0uZRKJ8yygy8TCq8Kj9ksTZLenqOauVdPspIPhyNT8kHTeUk1Cv5sTrzHHvVM3KjCqRRikWOE3goGbcTVCiCIux9DhD5hH1_vpN5hI9qSKSyNFg4Tw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Chen, M.L.; Ying, H.Z.; Wang, D.J.; Hu, F.L. Effects of Worker Bee Larvae on Immune Function in Mice. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkGgT-bLDHIciXpgxw0-1l-tY4LEn1ZVL3mWXPRzpeFIjCibBlzRk7sGeKW5rVdFX_xdohMDbs1ck1ZnbP8_3-Fb0SKOtuQXK9xQfcEAb-I5TOa5mQkWm8uTZNQcXypbIivIEqis9iuJBzr9MjyR9FyoQET-C_T92ugDTKwQgV5SoQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 11 September 2025).

| Protein | Amino Acids | Fat | Ash | Total Carbohydrates | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Kjeldahl method) | ||||||

| Kp 6.25 | Kp 5.6 | |||||

| — | 22.10 | — | 19.8 | 4.0 | 54.1 | [31] |

| 55.80 | — | 46.67 | 18.64 | 6.32 | 19.24 | [17] |

| 51.35 | — | — | — | 4.95 | 17.48 | [47] |

| 48.70 | — | 37.30 (not defatted) | — | — | — | [23] |

| — | 39.72 (defatted) | — | — | — | ||

| — | 19.00 | — | 28.1 | 2.8 | 50.1 | [30] |

| — | — | 47.57 | — | — | — | [45] |

| 48.44 | — | 41.68 | 15.00 | 4.48 | 32.08 | [21] |

| 44.28 | — | — | 23.9 | 3.41 | 23.8 | [48] |

| 41.50 | — | — | 15.71 | — | 11.6 | [49] |

| 53.45 | — | 45.83 | 19.73 | 3.71 | 13.99 | [10] |

| Amino Acids | Content (g/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Aspartic Acid | 5.48 |

| Serine | 1.66 |

| Glutamic Acid | 5.40 |

| Glycine | 2.09 |

| Histidine | 1.37 |

| Arginine | 2.25 |

| Threonine | 1.65 |

| Alanine | 2.22 |

| Proline | 2.01 |

| Tyrosine | 1.37 |

| Valine | 2.89 |

| Methionine | 0.84 |

| Isoleucine | 2.49 |

| Leucine | 3.45 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.07 |

| Lysine | 3.74 |

| Tryptophan | 0.44 |

| Biological Activity | Component | Experimental Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-oxidant | Acidic-extracted crude protein | In vitro (ABTS, Griess) | [23] |

| Acidic-extracted protein hydrolysate | |||

| QBLP | C57BL/6J mice (D-gal-induced aging) | [25] | |

| QBLP | Naturally aged Wistar rats | [51] | |

| Freeze-Dried QBLP | In vitro assays (DPPH) | [30,52,53,54] | |

| Anti-Aging | QBLP | Musca domestica | [55] |

| NIH mice | |||

| QBLP | Caenorhabditis elegans (N2) | [24] | |

| Acidic-extracted crude protein | In vitro enzyme inhibition assay | [23] | |

| QBLP | C57BL/6J mice (D-gal-induced aging) | [25] | |

| Metabolic Regulation | Freeze-Dried QBLP | Hy-Line Brown laying hens | [56] |

| Production Performance | Freeze-Dried QBLP | Hy-Line Brown laying hens | [56] |

| Anti-fatigue | QBLP | Kunming mice | [49] |

| Ameliorates obesity | Freeze-Dried QBLP | Diet-induced obese mice | [12] |

| Gut Microbiota Modulation | Freeze-Dried QBLP | C57BL/6J mice (D-gal-induced aging) | [25] |

| Anti-Insomnia | Freeze-Dried QBLP | C57BL/6 mice (PCPA-induced insomnia) | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, P.; Yu, X.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, B.; Li, S.; Hu, F. Recent Advances on Queen Bee Larvae: Sources, Chemical Composition, and Health-Benefit Bioactivities. Foods 2026, 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010089

Liang P, Yu X, Zhu M, Yuan B, Li S, Hu F. Recent Advances on Queen Bee Larvae: Sources, Chemical Composition, and Health-Benefit Bioactivities. Foods. 2026; 15(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Pengbo, Xinyu Yu, Meifei Zhu, Bin Yuan, Shanshan Li, and Fuliang Hu. 2026. "Recent Advances on Queen Bee Larvae: Sources, Chemical Composition, and Health-Benefit Bioactivities" Foods 15, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010089

APA StyleLiang, P., Yu, X., Zhu, M., Yuan, B., Li, S., & Hu, F. (2026). Recent Advances on Queen Bee Larvae: Sources, Chemical Composition, and Health-Benefit Bioactivities. Foods, 15(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010089