Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction and Hydrogel Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Bean Processing Waste

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Phenolic Extraction

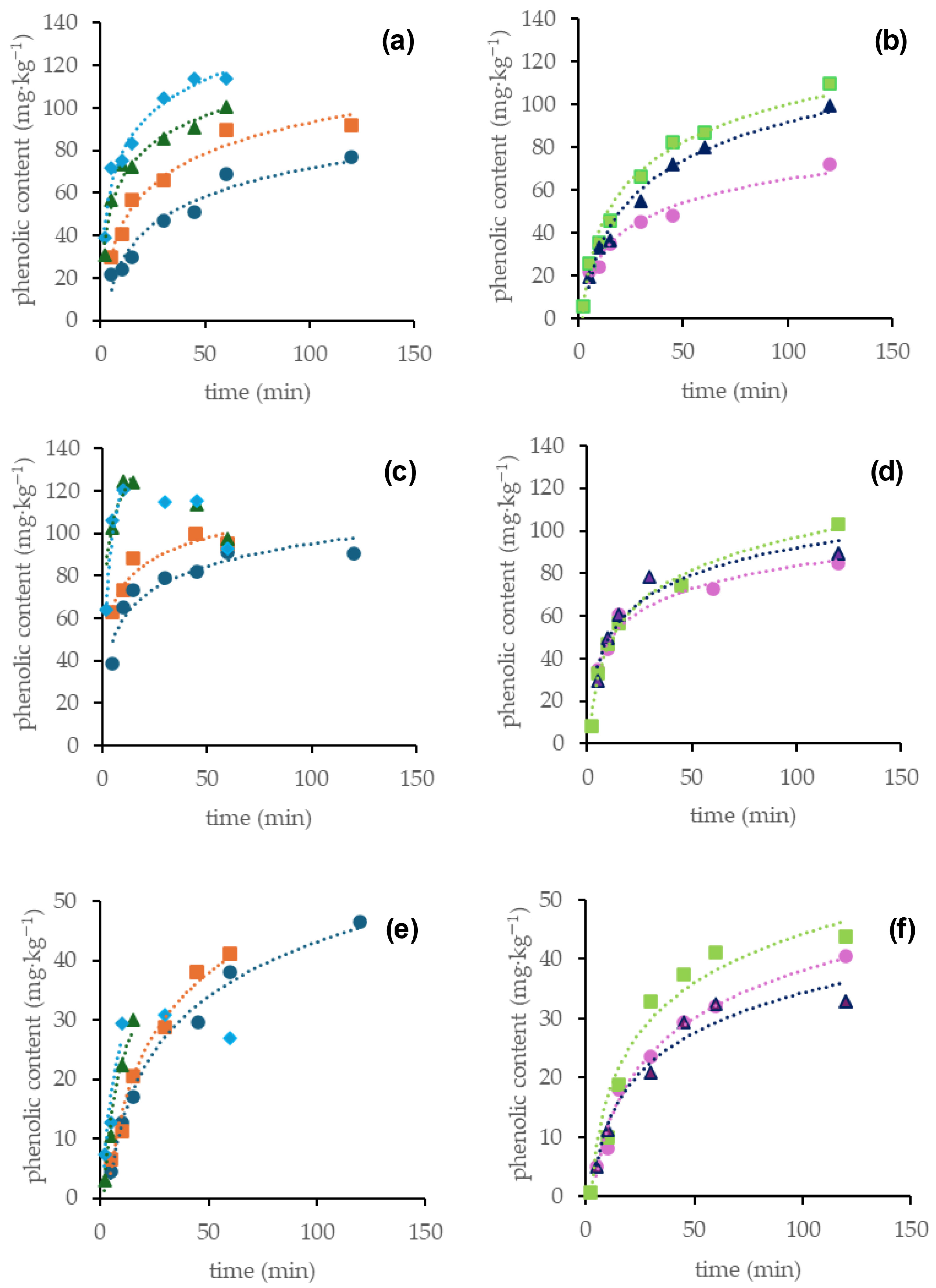

2.3. Extraction Kinetic Models

2.4. Phenolic Encapsulation in Alginate and Alginate/Chitosan Hydrogel Microbeads

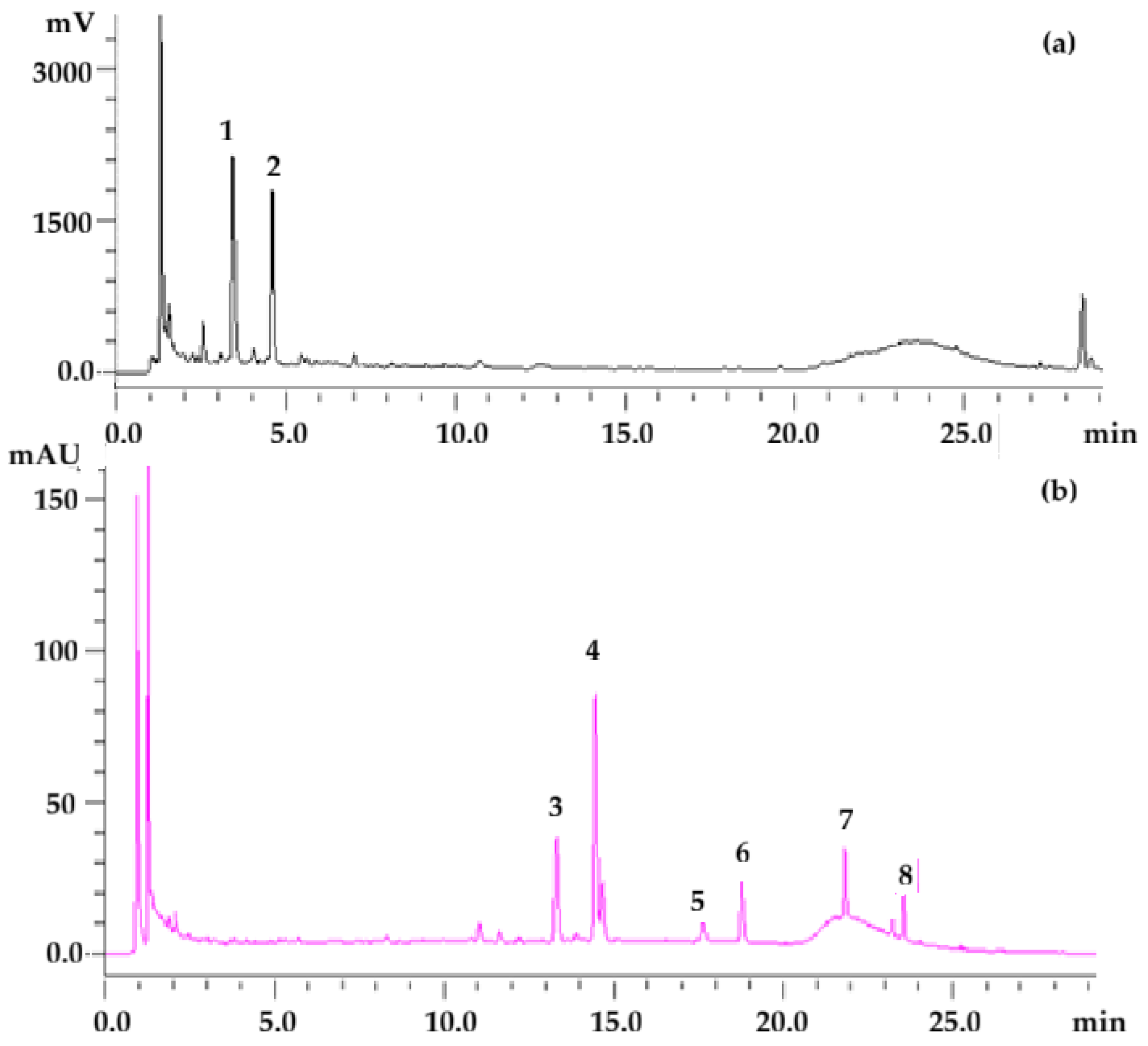

2.5. Phenolic Analysis by HPLC

2.6. Ferric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.7. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl Radical (DPPH) Scavenging Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Solvent Type and US-Assisted Extraction on Polyphenol Recovery

3.2. Modeling of Extraction Kinetics

3.3. Encapsulation of Polyphenols in Alginate and Alginate/Chitosan Hydrogel Microbeads

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations for chemical compounds and analyses are used in this manuscript: | |

| P-B1 | procyanidin B1 |

| C | catechin |

| K | kaempferol |

| Q | quercetin |

| Q-G | quercetin-3-O-glucoside + quercetin-3-O-glucuronide |

| R | rutin |

| u-F1 and u-F2 | unidentified flavonols |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| FRAP | Ferric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| The following abbreviations for physical processes and relative modeling are used in this manuscript: | |

| AED | acoustic energy density |

| De | effective diffusivity |

| US | ultrasound |

| C (mg·kg−1) | concentration of phenolics at time t |

| Ce (mg·kg−1) | maximum concentration of phenolics extracted after infinite time |

| f | fraction of accessible sites |

| kr (min−1) | rate constant for the rapid desorption phase |

| ks (min−1) | rate constant for the slow diffusion phase |

| k1 (min−1) | pseudo-first order rate constant |

| k2 (kg·mg−1·min−1) | pseudo-second order rate constant |

| r (m) | average particle radius. |

| The following abbreviations for statistical analysis are used in this manuscript: | |

| LSD | least significant difference |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| R | coefficient of correlation |

| R2 | coefficient of determination |

| SE | standard error |

References

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Shevkani, K.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A. Bioactive Constituents in Pulses and their Health Benefits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD; FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024–2033; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Imbesi, M.; Ingegneri, M.; Rando, R.; Mandrone, M.; Chiocchio, I.; Poli, F.; Trombetta, D. From Waste to Resource: Nutritional and Functional Potential of Borlotto Bean Pods (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Antioxidants 2025, 14, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakopic, J.; Slatnar, A.; Petkovsek, M.M.; Veberic, R.; Stampar, F.; Bavec, F.; Bavec, M. Effect of Different Production Systems on Chemical Profiles of Dwarf French Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Top Crop) Pods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2392–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Yang, W.T.; Cho, K.M.; Lee, J.H. Comparative Analysis of Isoflavone Aglycones using Microwave-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis from Soybean Organs at Different Growth Times and Screening for their Digestive Enzyme Inhibition and Antioxidant Properties. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabich, M.; Marciniak, B.; Kontek, R. Phenolic Compound Composition and Biological Activities of Fractionated Soybean Pod Extract. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksawasdi, N.; Taesuwan, S.; Prommajak, T.; Techapun, C.; Khonchaisri, R.; Sittilop, N.; Halee, A.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Phongthai, S.; Nunta, R.; et al. Ultrasonic Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Green Soybean Pods and Application in Green Soybean Milk Antioxidants Fortification. Foods 2022, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendri, L.B.; Chaari, F.; Kallel, F.; Koubaa, M.; Zouari-Ellouzi, S.; Kacem, I.; Chaabouni, S.E.; Ghiribi-Aydi, D. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Polyphenols Extracted from Pea and Broad Bean Pods Wastes. Food Meas. 2022, 16, 4822–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seling, G.S.; Rivero, R.C.; Sisi, C.V.; Busch, V.M.; Buera, M.P. Integrated Approach for the Optimization of the Sustainable Extraction of Polyphenols from a South American Abundant Edible Plant: Neltuma ruscifolia. Foods 2025, 14, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaskova, A.; Mlcek, J. New Insights of the Application of Water or Ethanol-Water Plant Extract Rich in Active Compounds in Foods. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1118761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Ahsan, H.; Zia, M.K.; Siddiqui, T.; Khan, F.H. Understanding Oxidants and Antioxidants: Classical Team with new Players. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Q.; Gan, R.-Y.; Ge, Y.-Y.; Zhang, D.; Corke, H. Polyphenols in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Chemistry, Analysis, and Factors Affecting Composition. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1518–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Meullemiestre, A.; Turk, M.; Perino, S.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Abert-Vian, M. Review of Green Food Processing Techniques. Preservation, Transformation, and Extraction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 41, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénicaud, C.; Guilbert, S.; Peyron, S.; Gontard, N.; Guillard, V. Oxygen Transfer in Foods Using Oxygen Luminescence Sensors: Influence of Oxygen Partial Pressure and Food Nature and Composition. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Abraham, T.E. Polyionic Hydrocolloids for the Intestinal Delivery of Protein Drugs: Alginate and Chitosan—A Review. J. Control. Release 2006, 114, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennacef, C.; Desobry-Banon, S.; Probst, L.; Desobry, S. Advances on Alginate Use for Spherification to Encapsulate Biomolecules. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobroslavić, E.; Cegledi, E.; Robić, K.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Repajić, M. Encapsulation of Fennel Essential Oil in Calcium Alginate Microbeads via Electrostatic Extrusion. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.; Rut, A.; Costa, P.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Estevinho, B.N. Design of Polymeric Delivery Systems for Lycium barbarum Phytochemicals: A Spray Drying Approach for Nutraceuticals. Foods 2025, 14, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, G.; Woltering, E.J.; Mozafari, M.R. Applications of Chitosan-Based Carrier as an Encapsulating Agent in Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Ijaz, M.; Li, M.; Woldemariam, K.Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, D. Impacts of Chitosan Coating on Shelf Life and Quality of Ready-to-Cook Beef Seekh Kabab During Refrigeration Storage. Foods 2025, 14, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilaș, S.; Raț, M.; Munteanu, F.-D. Biowaste Valorisation and Its Possible Perspectives Within Sustainable Food Chain Development. Processes 2025, 13, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomah, D.B.; Cardador-Martınez, A.; Loarca-Pina, G. Phenolics and Antioxidative Activities in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Nieto, M.; Blair, M.-W.; Welch, R.M.; Glahn, R.P. Screening of Iron Bioavailability Patterns in Eight Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Genotypes Using the Caco-2 Cell In Vitro Model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7950–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, D.-W. Kinetic Modeling of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Grape Marc: Influence of Acoustic Energy Density and Temperature. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harouna-Oumarou, H.A.; Fauduet, H.; Porte, C.; Ho, Y.-S. Comparison of Kinetic Models for the Aqueous Solid-Liquid Extraction of Tilia Sapwood in a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2007, 194, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelo, M.; Zornoza, B.; Meyer, A.S. Selective Release of Phenols from Apple Skin: Mass Transfer Kinetics during Solvent and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrali, D.; Barbarito, S.; Lavelli, V. Encapsulation of Grape Seed Phenolics from Winemaking Byproducts in Hydrogel Microbeads—Impact of Food Matrix and Processing on the Inhibitory Activity towards α-Glucosidase. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 133, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenț, O.D.; Duteanu, N.; Teusdea, A.C.; Ciocan, S.; Vicaș, L.; Jurca, T.; Muresan, M.; Pallag, A.; Ianasi, P.; Marian, E. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan-Alginate Microspheres Loaded with Quercetin. Polymers 2022, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Giusti, M.M.; Kaletunc, G. Encapsulation of Purple Corn and Blueberry Extracts in Alginate-Pectin Hydrogel Particles: Impact of Processing and Storage Parameters on Encapsulation Efficiency. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, G.; Bari, E.; Candiani, A.; Torre, M.L.; Picco, A.; Segale, L.; Milanesi, A.; Stampini, M.; Giovannelli, L. Chitosan for Improved Encapsulation of Thyme Aqueous Extract in Alginate-Based Microparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonassi, G.; Lavelli, V. Hydration and Fortification of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) with Grape Skin Phenolics—Effects of Ultrasound Application and Heating. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, W.; Liang, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, R.; Xie, D.; Xiang, D.; Feng, S.; Chen, T.; et al. A Cascade Approach to Valorizing Camellia oleifera Abel Shell: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Coupled with Resin Purification for High-Efficiency Production of Multifunctional Polyphenols. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuereb, M.A.; Psakis, G.; Attard, K.; Lia, F.; Gatt, R. A Comprehensive Analysis of Non-Thermal Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Peel Waste Through a One-Factor-at-a-Time Approach. Molecules 2025, 30, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsampa, P.; Valsamedou, E.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. A Green Utrasound-Assisted Extraction Process for the Recovery of Antioxidant Polyphenols and Pigments from Onion Solid Wastes Uing Box–Behnken Experimental Design and Kinetics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xie, H.; Huang, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, L. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Pine Needles (Pinus elliottii): Comprehensive Insights from RSM Optimization, Antioxidant activity, UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS/MS Analysis and Kinetic Model. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 102, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Shen, J.; Luo, J.; Li, D.; Tao, Y.; Song, C.; Han, Y. Simultaneous Extraction and Preliminary Purification of Polyphenols from Grape Pomace using an Aqueous Two-Phase System Exposed to Ultrasound Irradiation: Process Characterization and Simulation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 993475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, V.B.; Holkem, A.T.; Thomazini, M.; Petta, T.; Tulini, F.L.; de Oliveira, C.A.F.; Genovese, M.I.; da Costa Rodrigues, C.E.; Fávaro Trindade, C.S. Study of Extraction Kinetics and Characterization of Proanthocyanidin-rich Extract from Ceylon Cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Correa, E.; Bastías-Montes, J.M.; Acuna-Nelson, S.; Munoz-Farina, O. Effect of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents on Polyphenols Extraction from Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Bean Shells and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts. J. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essifi, K.; Brahmi, M.; Berraaouan, D.; Ed-Daoui, A.; El Bachiri, A.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Tahani, A. Influence of Sodium Alginate Concentration on Microcapsules Properties Foreseeing the Protection and Controlled Release of Bioactive Substances. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5531479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhotohwo, O.L.; Pacetti, D.; Lucci, P.; Jaiswal, S. Development and Optimisation of Sodium Alginate and Chitosan Edible Films with Sea Fennel By-product Extract for Active Food Packaging. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 226, 117960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Jiang, X.; Meng, Q.; Jiang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, J. Preparation of Nanoparticles Loaded with Quercetin and Effects on Bacterial Biofilm and LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress in Dugesia japonica. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizpurua-Olaizola, O.; Navarro, P.; Vallejo, A.; Olivares, M.; Etxebarria, N.; Usobiaga, A. Microencapsulation and Storage Stability of Polyphenols from Vitis vinifera Grape Wastes. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C. Microencapsulation of Grape Skin Phenolics for pH Controlled Release of Antiglycation Agents. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bušic, A.; Belšcak-Cvitanovic, A.; Vojvodic Cebin, A.; Karlovic, S.; Kovac, V.; Špoljaric, I.; Mršic, G.; Komes, D. Structuring New Alginate Network Aimed for Delivery of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Polyphenols Using Ionic Gelation and New Filler Materials. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.A.; Ozaltin, K.; Bernal-Ballen, A.; Di Martino, A. Chitosan-Alginate Hydrogels for Simultaneous and Sustained Releases of Ciprofloxacin, Amoxicillin and Vancomycin for Combination Therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Bao, Y.; Liang, C.; He, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, S. Chitosan-Based Dihydromyricetin Composite Hydrogel Demonstrating Sustained Release and Exceptional Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 139128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenolic Compounds (mg·kg−1) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent and Extraction Conditions | P-B1 | C | R | Q-G | u-F1 | u-F2 | Q | K | Sum |

| 80% Ethanol in water, 25 °C, 120 min | 5.0 a | 4.6 a | 6.6 a | 19 a | 7.6 a | 23 a | 25 d | 32 e | 122 a |

| 40% Ethanol in 10 mN HCl, 25 °C, 120 min | 9.7 b | 23 c | 26 b | 62 bc | 7.3 a | 28 a | 20 c | 17 ab | 195 b |

| Water, 30 °C, 120 min | 62 e | 9.9 b | 26 b | 59 b | 45 b | 112 b | 15 b | 25 d | 355 c |

| Water, 45 °C, 120 min | 79 g | 30 d | 32 cd | 71 cd | 61 c | 132 c | 18 bc | 27 d | 449 f |

| Water, 60 °C, 120 min | 66 f | 33 e | 25 b | 65 bc | 57 c | 107 b | 11 a | 21 c | 384 d |

| Water, 50 W·L−1, 30 °C, 60 min | 47 c | 22 c | 31 c | 68 cd | 57 c | 137 c | 15 b | 20 bc | 399 e |

| Water, 140 W·L−1, 30 °C, 45 min | 69 f | 22 c | 31 c | 72 d | 59 c | 161 d | 15 b | 23 cd | 450 f |

| Water, 240 W·L−1, 30 °C, 30 min | 54 d | 29 d | 35 d | 80 e | 81 d | 222 e | 16 b | 17 ab | 534 g |

| Water, 350 W·L−1, 30 °C, 15 min | 51 d | 32 de | 39 e | 82 e | 81 d | 220 e | 16 b | 16 a | 537 e |

| Pooled SE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ce (mg·kg−1) | k1 (min−1) | R2 | MAE (mg·kg−1) | RMSE (mg·kg−1) | De·1011 (m2·s−1) | R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||||||

| 30 °C | 317 | 0.097 | 91 | 18 | 24 | 3.4 | 0.88 |

| 45 °C | 425 | 0.105 | 97 | 23 | 39 | 4.8 | 0.91 |

| 60 °C | 394 | 0.094 | 99 | 5 | 8 | 2.7 | 0.93 |

| US, W·L−1 50, 30 °C | 358 | 0.118 | 92 | 26 | 25 | 6.3 | 0.95 |

| US, W·L−1 140, 30 °C | 410 | 0.148 | 88 | 30 | 31 | 12 | 0.96 |

| US, W·L−1 240, 30 °C | 548 | 0.248 | 99 | 4 | 5 | 232 | 0.94 |

| US, W·L−1 350, 30 °C | 546 | 0.480 | 97 | 4 | 7 | 460 | 0.97 |

| Flavanols | |||||||

| 30 °C | 69 | 0.036 | 91 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 2.2 | 0.95 |

| 45 °C | 105 | 0.049 | 98 | 4.3 | 9.2 | 3.9 | 0.99 |

| 60 °C | 99 | 0.03 | 97 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 0.99 |

| US, W·L−1 50, 30 °C | 77 | 0.033 | 93 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 4.1 | 0.98 |

| US, W·L−1 140, 30 °C | 90 | 0.069 | 96 | 3.8 | 5.9 | 18 | 0.99 |

| US, W·L−1 240, 30 °C | 95 | 0.15 | 87 | 7.3 | 9.7 | 70 | 0.90 |

| US, W·L−1 350, 30 °C | 106 | 0.25 | 85 | 8.8 | 11 | 226 | 0.98 |

| Quercetin derivatives | |||||||

| 30 °C | 73 | 0.098 | 93 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 0.91 |

| 45 °C | 95 | 0.103 | 97 | 6.9 | 21 | 4.3 | 0.92 |

| 60 °C | 88 | 0.08 | 99 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 0.85 |

| US, W·L−1 50, 30 °C | 87 | 0.13 | 95 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 0.91 |

| US, W·L−1 140, 30 °C | 95 | 0.18 | 89 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 81 | 0.94 |

| US, W·L−1 240, 30 °C | 123 | 0.34 | 97 | 7.7 | 23 | 293 | 0.97 |

| US, W·L−1 350, 30 °C | 123 | 0.38 | 99 | 7.3 | 22 | 356 | 0.95 |

| Flavonol aglycones | |||||||

| 30 °C | 52 | 0.027 | 98 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.98 |

| 45 °C | 57 | 0.038 | 94 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 10 | 0.99 |

| 60 °C | 43 | 0.037 | 98 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 0.99 |

| US, W·L−1 50, 30 °C | 61 | 0.026 | 98 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 0.98 |

| US, W·L−1 140, 30 °C | 63 | 0.031 | 99 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 9.6 | 0.98 |

| US, W·L−1 240, 30 °C | 52 | 0.085 | 98 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 46 | 0.99 |

| US, W·L−1 350, 30 °C | 67 | 0.085 | 95 | 13.0 | 36 | 67 | 0.89 |

| Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Alginate/Chitosan | |

| C | 35 aA ± 6 | 32 aA ± 2 |

| P-B1 | 65 bcA ± 4 | 66 bcA ± 1 |

| R | 56 bA ± 1 | 59 bA ± 2 |

| Q-G | 56 bA ± 3 | 69 cA ± 4 |

| u-F1 | 64 bcA ± 8 | 72 cdA ± 8 |

| u-F2 | 66 cA ± 1 | 89 eB ± 4 |

| Q | 79 dA ± 2 | 88 eB ± 2 |

| K | 65 bcA ± 6 | 87 eB ± 3 |

| sum | 53 A ± 1 | 64 B ± 3 |

| FRAP | 67 A ± 1 | 71 B ± 1 |

| DPPH | 63 A ± 1 | 69 B ± 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bosio, A.; Beccaria, M.; Lavelli, V. Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction and Hydrogel Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Bean Processing Waste. Foods 2026, 15, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010030

Bosio A, Beccaria M, Lavelli V. Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction and Hydrogel Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Bean Processing Waste. Foods. 2026; 15(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosio, Alessandro, Matteo Beccaria, and Vera Lavelli. 2026. "Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction and Hydrogel Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Bean Processing Waste" Foods 15, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010030

APA StyleBosio, A., Beccaria, M., & Lavelli, V. (2026). Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction and Hydrogel Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Bean Processing Waste. Foods, 15(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010030