Artificial Intelligence-Driven Food Safety: Decoding Gut Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects of Non-Microbial Contaminants

Abstract

1. Introduction

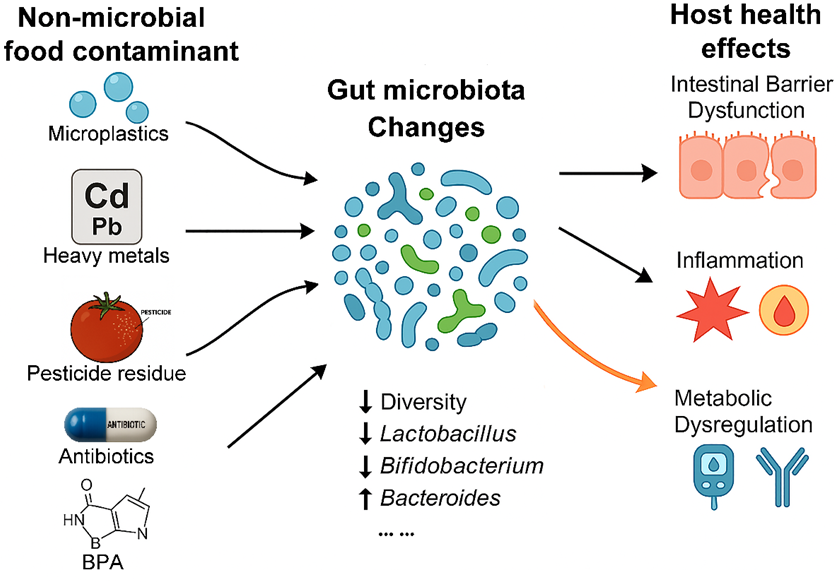

2. Non-Microbial Chemical Contaminants in Food Chain and Their Interactions with Gut Microbiota

2.1. Micro- (Nano-)Plastics in Food and Their Interactions with Gut Microbiota

2.2. Heavy Metal Contamination in Food and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis

2.3. Pesticide Residues in the Food Supply and Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects

2.4. Antibiotic and Veterinary Drug Residues in Food and the Gut Resistome

2.5. Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) and the “POPs–Microbiota–Host” Axis

2.6. Other Foodborne Chemical Contaminants Affecting the Gut Microbiota

2.7. Co-Exposure and Comprehensive Analysis

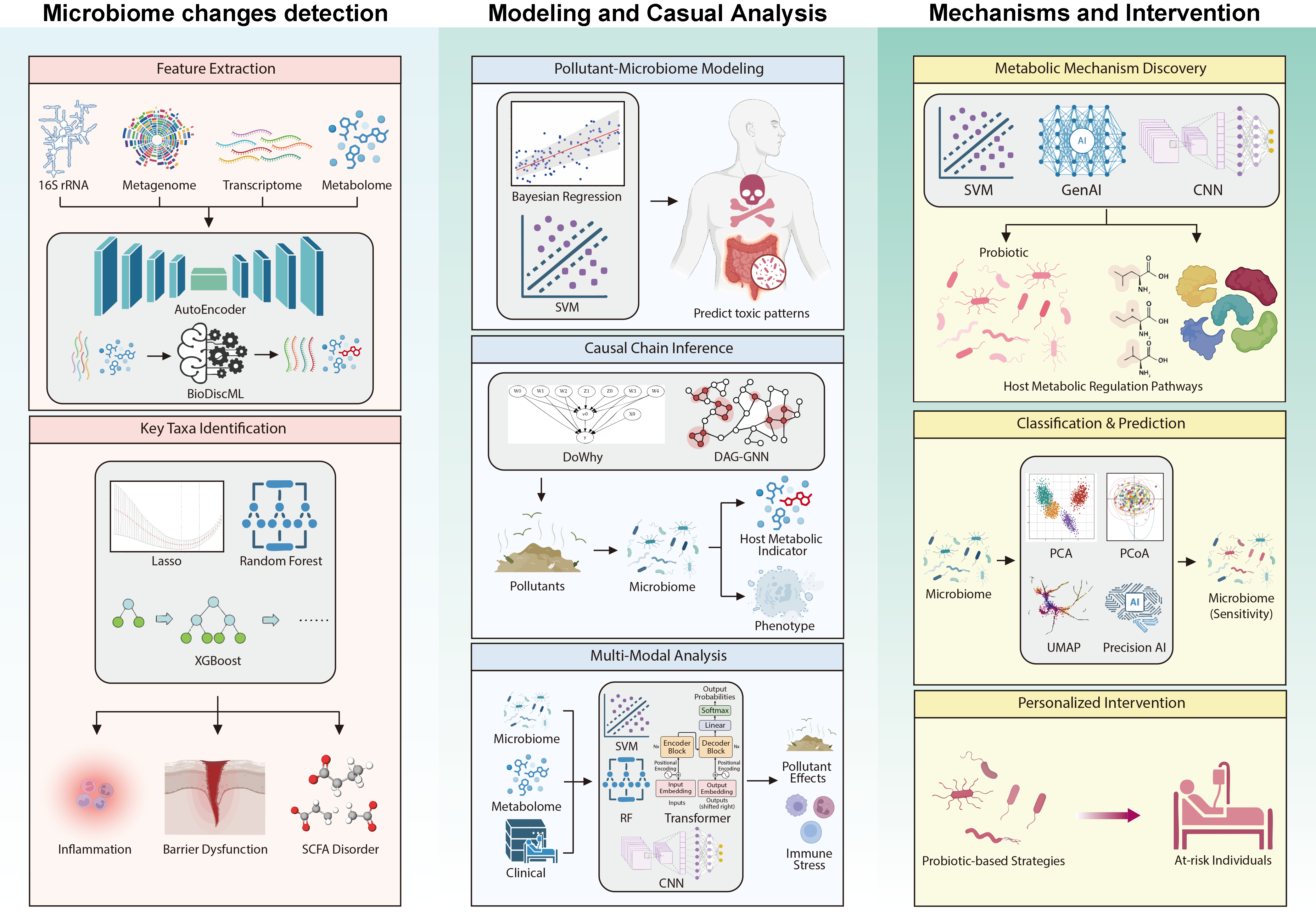

3. AI Enables the Analysis of Non-Microbial Contaminant–Gut Microbiota–Host Interactions

3.1. AI-Assisted Deciphering of Gut Microbiota Changes Induced by Non-Microbial Contaminants

3.1.1. AI for Microbiome Characterization and Dysbiosis Mapping

3.1.2. AI for Identifying Key Bacterial Genera or Metabolic Pathways Highly Correlated with Contaminant Exposure

3.2. Modeling and Prediction of the Relationship Between Non-Microbial Contaminant and Gut Microbiota

3.2.1. Prediction of Interaction Between Non-Microbial Food Contaminants and Gut Microbiota

3.2.2. Causal Inference of “Toxicity Causal Chains”

3.2.3. AI-Driven Multimodal Data Integration

3.3. AI-Driven Analysis of Metabolic Mechanisms and Gut Microbiota-Targeted Interventions of Non-Microbial Contaminants on Health

3.3.1. Mechanistic Insights of Non-Microbial Contaminants Through Gut Microbiota Interventions in Host Health

3.3.2. Prediction of Individualized Toxicity Responses and Identification of Sensitive Contaminants

3.3.3. AI-Assisted Intervention Design for Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Induced by Non-Microbial Contaminants

4. AI Applications in the Interaction of Microplastics and Gut Microbiota: Case Study

5. Challenges and Perspectives

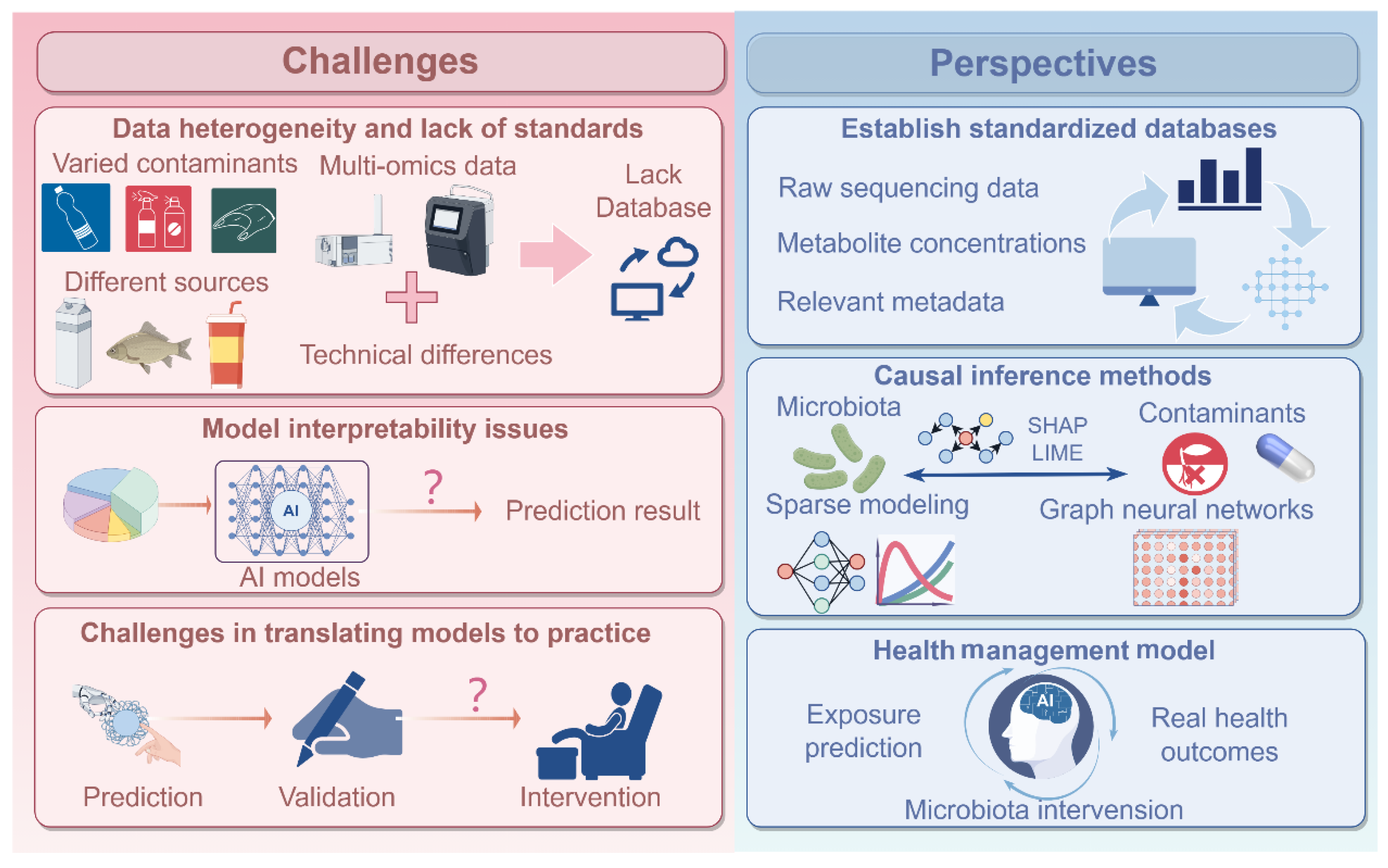

5.1. Data Heterogeneity and Lack of Standards

5.2. Model Interpretability Issues

5.3. Challenges in Translating Models into Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; Xi, Y.; Li, S. Comprehensive review of emerging contaminants: Detection technologies, environmental impact, and management strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, T.R.; Stolz, J.F.; Oremland, R.S. Arsenic and the gastrointestinal tract microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackelmann, G.; Sommer, S. Microplastics and the gut microbiome: How chronically exposed species may suffer from gut dysbiosis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 143, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmassry, M.M.; Zayed, A.; Farag, M.A. Gut homeostasis and microbiota under attack: Impact of the different types of food contaminants on gut health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 738–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sille, F.C.M.; Busquet, F.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Herrmann, K.; Leenhouts-Martin, L.; Luechtefeld, T.; Maertens, A.; Miller, G.W.; Smirnova, L.; Tsaioun, K.; et al. The implementation moonshot project for alternative chemical testing (IMPACT) toward a human exposome project. ALTEX 2024, 41, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, A.; Fiannaca, A.; La Rosa, M.; Urso, M.A.; La Paglia, L. A deep learning multi-omics framework to combine microbiome and metabolome profiles for disease classification. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Lugano, Switzerland, 17–20 September 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A.C.; Lapkin, J.; Yin, Q.; Muller, E.; Almeida, A. Meta-analysis of the uncultured gut microbiome across 11,115 global metagenomes reveals a new candidate biomarker of health. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelfaoui, I.; Wang, W.; Meskher, H.; Shehata, A.I.; El Basuini, M.F.; Abouelenein, M.F.; Degha, H.E.; Alhoshy, M.; Teiba, I.I.; Mahmoud, S.S. Beyond just correlation: Causal machine learning for the microbiome, from prediction to health policy with econometric tools. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1691503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezapour Shiri, F.; Perumal, T.; Mohamed, R. A comprehensive overview and comparative analysis on deep learning model. J. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 301–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Rho, M. Multimodal deep learning applied to classify healthy and disease states of human microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekinwala, N.L.; Bhushan, M. Generalised non-negative matrix factorisation for air pollution source apportionment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 156294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M.; Bathi, J.R.; Khan, E.; Katyal, D.; Danquah, M.J. Microplastics in ecosystems: Critical review of occurrence, distribution, toxicity, fate, transport, and advances in experimental and computational studies in surface and subsurface water. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.; Azfaralariff, A.; Musa, S.M.; Mohamed, M.; Yusoff, A.H.; Lazim, A.M. Occurrence, distribution and characteristics of microplastics in gastrointestinal tract and gills of commercial marine fish from Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Liu, H.; Zhu, T.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, Q.J. Toxic effects of micro (nano)-plastics on terrestrial ecosystems and human health. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 172, 117517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, C.; Lindeque, P.K.; Thompson, R.; Tolhurst, T.; Cole, M. Microplastics and seafood: Lower trophic organisms at highest risk of contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, H.; He, Y.; Sun, H.; Tang, J.; Xing, B. Plastic takeaway food containers may cause human intestinal damage in routine life usage: Microplastics formation and cytotoxic effect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Kooi, M.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Lifetime accumulation of microplastic in children and adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellus, K.A.; Prescott, D.; Scur, M.; Ross, N.; Gill, S. Exposure of polystyrene nano- and microplastics in increasingly complex in vitro intestinal cell models. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzfischer, M.; Rogler, G. The intestinal barrier—Shielding the body from nano- and microparticles in our diet. Metabolites 2022, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wan, Z.; Luo, T.; Fu, Z.; Jin, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: Common threads and missing links. Cell 2012, 148, 852–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, E.; Ratel, J.; Denis, S.; Leveque, M.; Ruiz, P.; Mazal, C.; Amiard, F.; Edely, M.; Bezirard, V.; Gaultier, E.; et al. Exposure to polyethylene microplastics alters immature gut microbiome in an infant in vitro gut model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Hu, M.; Jiang, J.; Dai, M.; Wang, B.J.P.; et al. Underestimated health risks: Polystyrene micro-and nanoplastics jointly induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by ROS-mediated epithelial cell apoptosis. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ran, L.; He, Y.; Huang, Y. Mechanisms of microplastics on gastrointestinal injury and liver metabolism disorder. Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C. Microplastics and human health: Integrating pharmacokinetics. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Vethaak, A.D.; Lavorante, B.R.; Lundebye, A.-K.; Guilhermino, L. Marine microplastic debris: An emerging issue for food security, food safety and human health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Tiwari, N.; Singh, D.; Tripathi, P.; Sharma, S.; Research, P. Toxicological impacts of microplastics on human health: A bibliometric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 57417–57429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achary, M.S.; Satpathy, K.K.; Panigrahi, S.; Mohanty, A.K.; Padhi, R.K.; Biswas, S.; Prabhu, R.K.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Panigrahy, R.C. Concentration of heavy metals in the food chain components of the nearshore coastal waters of Kalpakkam, southeast coast of India. Food Control 2017, 72, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Lee, S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.; Kim, K. Heavy metals in food crops: Health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Zhai, Q.; Fan, L.; Chen, W. Gut microbiota: A target for heavy metal toxicity and a probiotic protective strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkov, A.A.; Gritsenko, V.A.; Skalnaya, M.G.; Cherkasov, S.V.; Aaseth, J.; Skalny, A.V. Gut as a target for cadmium toxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Lin, X.; Zhao, J.; Cui, L.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Y.-L.; Li, B.; Li, Y.-F. Gut as the target tissue of mercury and the extraintestinal effects. Toxicology 2023, 484, 153396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, X.; Hu, G.; Li, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, L.; Xing, C.; Zhang, C.; et al. Exposed to Mercury-Induced Oxidative Stress, Changes of Intestinal Microflora, and Association between them in Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Wen, F.; Yu, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, A. Neurotransmitter disturbances caused by methylmercury exposure: Microbiota-gut-brain interaction. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Wu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Fu, Z. Effects of environmental pollutants on gut microbiota. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, C.C.; Podar, M.; Bullock, A.L.; Graham, A.M.; Brown, S.D.; Somenahally, A.C.; Johs, A.; Hurt, R.A., Jr.; Bailey, K.L.; Elias, D.A. Mercury methylation by novel microorganisms from new environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11810–11820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, A.; Liang, G.; Jiao, B. Occurrence, temporal variation, quality and safety assessment of pesticide residues on citrus fruits in China. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authority, E.F.S.; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Marchese, E.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2023 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. Efsa J. 2025, 23, e9398. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, R.; Gunnigle, E.; Geissen, V.; Clarke, G.; Nagpal, J.; Cryan, J.F. Pesticide exposure and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Qian, Y.J. Host metabolic disorders induced by alterations in intestinal flora under dietary pesticide exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 6303–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Y. Association between umbilical blood organophosphate esters exposure and meconium microbiome of newborns. J. Environ. Occup. Med. 2024, 41, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Mu, H.; Hu, Y.-M. Determination of fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines multiresidues simultaneously in porcine tissue by MSPD and HPLC–DAD. J. Pharm. Anal. 2012, 2, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.; Okoh, A. Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: Potential public health implications. Molecules 2018, 23, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, R.E.; Nebot, C.; Veiga-Gómez, M.; Roca-Saavedra, P.; Vazquez Belda, B.; Franco, C.M.; Cepeda, A. A confirmatory method based on HPLC-MS/MS for the detection and quantification of residue of tetracyclines in nonmedicated feed. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016, 2016, 1202954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unitated States. The Impact of Veterinary Drug Residues on the Gut Microbiome and Human Health: A Food Safty Perspective; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen, L.; Relman, D.A. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4554–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Nian, L.; Kwok, L.Y.; Sun, T.; Zhao, J. Reduction in fecal microbiota diversity and short-chain fatty acid producers in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infected individuals as revealed by PacBio single molecule, real-time sequencing technology. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Deghel, N.; Rapinski, M.; Duboz, P.; Raymond, R.; Davy, D.; Durães, N.; Dendievel, A.-M.; da Silva, E.F.; Lopez, P.J.; Vaccher, V.J.F.C. Persistent organic pollutants in food systems: A comparative study across four contrasting socio-ecosystems: Portugal, Senegal, French Guiana, and Guadeloupe. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wong, C.; Zheng, J.; Bouwman, H.; Barra, R.; Wahlström, B.; Neretin, L.; Wong, M.H. Bisphenol A (BPA) in China: A review of sources, environmental levels, and potential human health impacts. Environ. Int. 2012, 42, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitos, I.A.; Topi, S.; Gagliano-Candela, R.; De Nitto, E.; Polimeno, L.; Montagnani, M.; Santacroce, L.J.E. The toxic effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on gut microbiota: Bisphenol A (BPA) a review. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2022, 22, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Tian, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Cai, D.; Sun, J.; Bai, W.; Jin, Y. Exposure to bisphenol A caused hepatoxicity and intestinal flora disorder in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Mao, L.; Zhou, F.; Shen, J.; Zhao, N.; Jin, H.; Hu, J.; Hu, Z. Influence of gut microbiota on metabolism of bisphenol A, a major component of polycarbonate plastics. Toxics 2023, 11, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tang, J.; Shen, D.; Li, Y.; Nagaoka, K.; Li, C. Bisphenol A exposure induces small intestine damage through oxidative stress, inflammation, and microbiota alteration in rats. Toxics 2025, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Koren, O.; Goodrich, J.K.; Poole, A.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Ley, R.E.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2015, 519, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P. Mycotoxin and Gut Microbiota Interactions. Toxics 2020, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Dave, P.H.; Kwong, R.W.M.; Wu, M.; Zhong, H. Influence of microplastics on the mobility, bioavailability, and toxicity of heavy metals: A review. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Q.; Li, N. Polystyrene may alter the cooperation mechanism of gut microbiota and immune system through co-exposure with DCBQ. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, M.S.; Avellar, M.C.W.; Perobelli, J.E. Could the gut microbiota be capable of making individuals more or less susceptible to environmental toxicants? Toxicology 2024, 503, 153751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Zhao, F. AI-empowered human microbiome research. Gut 2025, 335946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, G.; Rahman, G.; Martino, C.; McDonald, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Mishne, G.; Knight, R. Applications and comparison of dimensionality reduction methods for microbiome data. Front. Bioinform. 2022, 2, 821861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakan, T.; Gundogdu, A.; Alagözlü, H.; Ekmen, N.; Ozgul, S.; Hora, M.; Beyazgul, D.; Nalbantoglu, O.U. Artificial Intelligence based personalized diet: A pilot clinical study for IBS. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2138672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, N.; Lu, Y.; Cao, H. Identification of key genes in membranous nephropathy and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by bioinformatics and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1564288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Zhang, L. DeepMicro: Deep representation learning for disease prediction based on microbiome data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, M.; Vittrant, B.; Martin-Magniette, M.L.; Scott Boyer, M.P.; Perin, O.; Bergeron, A.; Fradet, Y.; Droit, A. Large-scale automatic feature selection for biomarker discovery in high-dimensional OMICs data. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamurias, A.; Jesus, S.; Neveu, V.; Salek, R.M.; Couto, F.M. Information retrieval using machine learning for biomarker curation in the Exposome-Explorer. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2020, 6, 689264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comertpay, B.; Gov, E.J.J.O.C.; Hepatology, E. Multiomics analysis and machine learning-based identification of molecular signatures for diagnostic classification in liver disease types along the microbiota-gut-liver axis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2025, 15, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.-P.; Chung, Y.-T.; Li, R.; Wan, H.-T.; Wong, C.K.-C. Bisphenol A alters gut microbiome: Comparative metagenomics analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphaisa, T.C.; Akinmoladun, O.F.; Adelusi, O.A.; Mwanza, M.; Fon, F.; Tangni, E.; Njobeh, P.B. Advances in mycotoxin detection techniques and the crucial role of reference material in ensuring food safety. A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 200, 115387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focker, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J. The use of artificial intelligence to improve mycotoxin management: A review. Mycotoxin Res. 2025, 41, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsoglou, G.; Tarazona, S.; Lopes, M.B.; Klammsteiner, T.; Ibrahimi, E.; Eckenberger, J.; Novielli, P.; Tonda, A.; Simeon, A.; Shigdel, R.; et al. Machine learning approaches in microbiome research: Challenges and best practices. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1261889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-W.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.-Y. Artificial intelligence for microbiology and microbiome research. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.01098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xiao, G.; Koh, A.Y.; Kim, J.; Li, Q.; Zhan, X.J.B. A Bayesian zero-inflated negative binomial regression model for the integrative analysis of microbiome data. Biostatistics 2021, 22, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, K.C.; Jiang, S.; Neugent, M.L.; De Nisco, N.J.; Zhan, X.; Li, Q. A survey of statistical methods for microbiome data analysis. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2022, 8, 884810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Reeve, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, J. GMPR: A robust normalization method for zero-inflated count data with application to microbiome sequencing data. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, W.D.; Argiento, R.; Guindani, M.; Galloway-Pena, J.; Shelburne, S.A.; Vannucci, M. An integrative Bayesian Dirichlet-multinomial regression model for the analysis of taxonomic abundances in microbiome data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G.-W.; Wu, Z.-G.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.-B.; Yao, Z.-W.; Yang, X.-Y.; Yu, Y.-B. Intestinal flora and inflammatory bowel disease: Causal relationships and predictive models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, T.; Zeng, J.; Guo, K.; Qiu, H.; Cheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W. Machine learning-causal inference based on multi-omics data reveals the association of altered gut bacteria and bile acid metabolism with neonatal jaundice. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2388805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhang, A.; Li, L.; Sun, Q.; He, J.; Wu, Y.; Tan, R.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; et al. Application of machine learning tools: Potential and useful approach for the prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the gut microbiome profile. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, T.; Yu, M. DAG-GNN: DAG structure learning with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 7154–7163. [Google Scholar]

- Rozera, T.; Pasolli, E.; Segata, N.; Ianiro, G. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in the multi-omics approach to gut microbiota. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, Q.; Varma, R.; Tataru, C.; David, M.M.; Fern, X. Learning a deep language model for microbiomes: The power of large scale unlabeled microbiome data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1011353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram Das, A.; Pillai, N.; Nanduri, B.; Rothrock, M.J.; Ramkumar, M. Exploring pathogen presence prediction in pastured poultry farms through transformer-based models and attention mechanism explainability. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, B.K.; Das, A. Artificial intelligence on beta-lactam research. In Chemistry and Biology of Beta-Lactams; Taylor & Francis Asia Pacific: Singapore, 2024; Volume 363. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Shum, M.H.-H.; Liao, Y.; Leung, V.W.; Gong, Y.-N.; Smith, D.K.; Yin, X.; Guan, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhang, T.; et al. ARGNet: Using deep neural networks for robust identification and classification of antibiotic resistance genes from sequences. Microbiome 2024, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, A.; Blekhman, R. Multi-omic approaches for host-microbiome data integration. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2297860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, F.; Broccolo, F. Applications of artificial intelligence in microbiome analysis and probiotic interventions—An overview and perspective based on the current state of the art. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asar, R.; Erenler, S.; Devecioglu, D.; Ispirli, H.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Ozturk, H.I.; Dertli, E. Understanding the functionality of probiotics on the edge of artificial intelligence (AI) era. Fermentation 2025, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Martino, C.; Rahman, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Mishne, G.; Knight, R. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Reveals composite patterns and resolves visualization artifacts in microbiome data. mSystems 2021, 6, e0069121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiman, D.; Farhat, A.M.; Dai, Y. Predicting host phenotype based on gut microbiome using a convolutional neural network approach. In Artificial Neural Networks; Cartwright, H., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hou, L.; Huang, Z. Exploring relationship between emotion and probiotics with knowledge graphs. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, G.; Yu, J.; Sung, J. Artificial intelligence and metagenomics in intestinal diseases. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Yang, M.; Teng, A.; Ni, C.; Wang, P.; Tang, S. Unraveling microplastic effects on gut microbiota across various animals using machine learning. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Paul, K.; Jacobs, J.P.; Cockburn, M.G.; Bronstein, J.M.; del Rosario, I.; Ritz, B. Ambient long-term exposure to organophosphorus pesticides and the human gut microbiome: An observational study. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xue, R.; Zong, X.; Jiang, X.; You, G.; Wei, Y.; Guo, B. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Food Safety: Decoding Gut Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects of Non-Microbial Contaminants. Foods 2026, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010022

Xue R, Zong X, Jiang X, You G, Wei Y, Guo B. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Food Safety: Decoding Gut Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects of Non-Microbial Contaminants. Foods. 2026; 15(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Ruizhe, Xinyue Zong, Xiaoyu Jiang, Guanghui You, Yongping Wei, and Bingbing Guo. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence-Driven Food Safety: Decoding Gut Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects of Non-Microbial Contaminants" Foods 15, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010022

APA StyleXue, R., Zong, X., Jiang, X., You, G., Wei, Y., & Guo, B. (2026). Artificial Intelligence-Driven Food Safety: Decoding Gut Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects of Non-Microbial Contaminants. Foods, 15(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010022