Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensory Properties of Organic Goat’s and Cow’s Fermented Whey Beverages with Kamchatka Berry, Blackcurrant, and Apple Juices Produced at a Laboratory and Technical Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

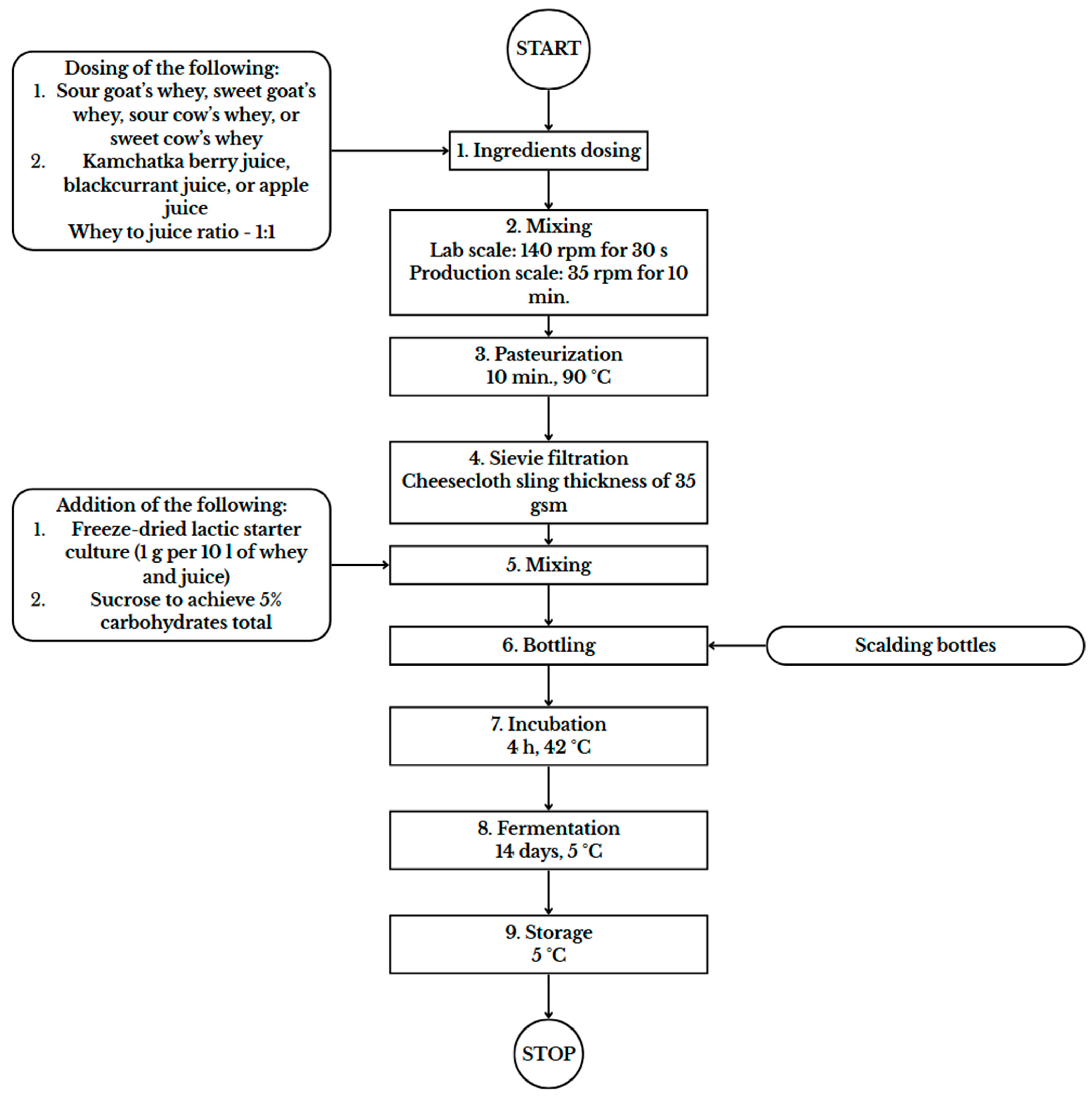

Preparation of Fermented Whey Drinks with the Addition of Organic Fruit Juices

2.2. Rheological Properties of Obtained Drinks

2.2.1. Apparent Viscosity

2.2.2. Dynamic Viscosity

2.3. Viscoelastic Properties

2.4. Physicochemical Properties of Obtained Drinks

2.4.1. pH Measurement

2.4.2. Determination of Titratable Acidity

2.5. Sensory Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rheological Properties of Fermented Whey Drinks

Apparent and Dynamic Viscosity

3.2. Viscoelastic Properties of Fermented Whey Drinks

3.3. Acidity of Obtained Drinks

pH Measurement and Determination of Titratable Acidity

3.4. Sensory Analysis of Fermented Whey Drinks

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.K.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, G. Trust, convenience and environmental concern in consumer purchase intention for organic food. Span. J. Mark.—ESIC 2023, 27, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodkowski, G.; Gołębiewski, M.; Slósarz, J.; Grodkowska, K.; Kostusiak, P.; Sakowski, T.; Puppel, K. Organic milk production and dairy farming constraints and prospects under the laws of the European Union. Animals 2023, 13, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepkowska, A.; Zielińska, D.; Ołdak, A.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Organic whey as a source of Lactobacillus strains with selected technological and antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, B.; Evrendilek, G.A. Whey beverages. In Dairy Foods: Processing, Quality, and Analytical Techniques; da Cruz, A.G., Ranadheera, C.S., Nazzaro, F., Mortazavian, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Duxford, UK, 2021; pp. 117–137. ISBN 9780128204788. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.I.F.; Barbosa, P.P.d.S.; Camargo, L.J.; Pinto, L.D.S.; Mataribu, B.; Serrão, C.; Marques-Santos, L.F.; Lopes, J.H.; de Oliveira, J.M.C.; Gadelha, C.A.d.A.; et al. Characterization of goat whey proteins and their bioactivity and toxicity assay. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Huma, N.; Pasha, I.; Sameen, A.; Mukhtar, O.; Khan, M.I. Chemical composition, nitrogen fractions and amino acids profile of milk from different animal species. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 29, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkçi, N.; Akdeniz, V.; Akalın, A.S. Probiotic whey-based beverages from cow, sheep and goat milk: Antioxidant activity, culture viability, amino acid contents. Foods 2023, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Ramos, M.; Gómez-Ruiz, J.Á. Bioactive components of ovine and caprine cheese whey. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 101, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduko, C.O.; Park, Y.W. Production of infant formula analogs by membrane fractionation of caprine milk: Effect of temperature treatment on membrane performance. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Powar, P.; Mehra, R. A review on nutritional advantages and nutraceutical properties of cow and goat milk. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2021, 7, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amao, I. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables: Review from Sub-Saharan Africa. In Vegetables-Importance of Quality Vegetables to Human Health; Asaduzzaman, M., Toshiki, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78923-507-4. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, J.; Gururani, P.; Vishnoi, S.; Srivastava, A. Whey based beverages: A review. Octa J. Biosci. 2020, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Heinmaa, L.; Moor, U.; Põldma, P.; Raudsepp, P.; Kidmose, U.; Lo Scalzo, R. Content of health-beneficial compounds and sensory properties of organic apple juice as affected by processing technology. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachtan-Janicka, J.; Ponder, A.; Hallmann, E. The effect of organic and conventional cultivations on antioxidants content in blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) species. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, A.; Reuben, S.C.; Ahmed, S.; Darvesh, A.S.; Hohmann, J.; Bishayee, A. The health benefits of blackcurrants. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W. Dietary polyphenols—Important non-nutrients in the prevention of chronic noncommunicable diseases. A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomisawa, T.; Nanashima, N.; Kitajima, M.; Mikami, K.; Takamagi, S.; Maeda, H.; Horie, K.; Lai, F.C.; Osanai, T. Effects of blackcurrant anthocyanin on endothelial function and peripheral temperature in young smokers. Molecules 2019, 24, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcar, J.; Kapusta, I.; Sekutowski, T.R.; Gorzelany, J. Impact of the addition of fruits of Kamchatka berries (L. caerulea var. kamtschatica) and haskap (L. caerulea var. emphyllocalyx) on the physicochemical properties, polyphenolic content, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation craft wheat beers. Molecules 2023, 28, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatović, M.L.; Krunić, T.; Vukašinović-Sekulić, M.S.; Zarić, D.B.; Rakin, M.B. Quality attributes of a fermented whey-based beverage enriched with milk and a probiotic strain. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 55503–55510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.; Bechshoeft, R.L.; Giacalone, D.; Otto, M.H.; Castro-Mejía, J.; Bin Ahmad, H.F.; Reitelseder, S.; Jespersen, A.P. Whey protein stories–An experiment in writing a multidisciplinary biography. Appetite 2016, 107, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A.; Lu, C.D. Current status of global dairy goat production: An overview. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoń, M.; Waraczewski, R.; Sołowiej, B.G. Organic Sea Buckthorn or Rosehip Juices on the Physicochemical, Rheological, and Microbial Properties of Organic Goat or Cow Fermented Whey Beverages. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-A-86061:2002; Mleko i Przetwory Mleczne–Mleko Fermentowane. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- Szczesniak, A.S. Texture is a sensory property. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.E.; Buiochi, F. Dynamic measurement of viscosity: Signal processing methodologies. Dynamics 2019, 91, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco V, M.M.; Porras, O.O.; Velasco, E.; Morales-Valencia, E.M.; Navarro, A. Effect of the milk-whey relation over physicochemical and rheological properties on a fermented milky drink. Ing. Y Compet. 2017, 19, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.J.; Southward, C.R.; Creamer, L.K. Protein hydration and viscosity of dairy fluids. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry—1 Proteins; Fox, P.F., McSweeney, P.L.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1289–1323. ISBN 978-1-4419-8602-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyńska-Mleko, M.; Ozimek, L. Ultrasound viscosity measurements allow determination of gas volume fraction in foamed gels. J. Food Process Eng. 2013, 36, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, Q.; Proestos, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, Q. The characteristics of whey protein and blueberry juice mixed fermentation gels formed by lactic acid bacteria. Gels 2023, 9, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitreli, G.; Thomareis, A.S. Instrumental textural and viscoelastic properties of processed cheese as affected by emulsifying salts and in relation to its apparent vscosity. Int. J. Food Prop. 2010, 12, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounsey, J.S.; O’Rlordan, E.D. Empirical and dynamic rheological data correlation to characterize melt characteristics of imitation cheese. J. Food Sci. 1999, 64, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Lu, M.; Wang, W.; Wa, Y.; Qu, H.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Ji, Q.; Gu, R. The quality and flavor changes of different soymilk and milk mixtures fermented products during storage. Fermentation 2022, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.N.; Guo, M.R. Effects of addition of strawberry juice pre- or postfermentation on physiochemical and sensory properties of fermented goat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 4978–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, D.; Piccinali, P.; Schreier, K. Effects of sugar substitution with Stevia, ActilightTM and Stevia combinations or PalatinoseTM on rheological and sensory characteristics of low-fat and whole milk set yoghurt. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkowski, M.; Błaszczyk, M. Charakterystyka fizjologiczno-biochemiczna bakterii fermentacji mlekowej. Kosmos 2012, 61, 493–504. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism characteristics of lactic acid bacteria and the expanding applications in food industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabokbar, N.; Khodaiyan, F. Characterization of pomegranate juice and whey based novel beverage fermented by kefir grains. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3711–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; de Pereira, G.V.M.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Microbial communities and chemical changes during fermentation of sugary Brazilian kefir. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejdlová, A.; Vašina, M.; Lorencová, E.; Hružík, L.; Salek, R.N. Assessment of different levels of blackcurrant juice and furcellaran on the quality of fermented whey-based beverages using rheological and mechanical vibration damping techniques. Foods 2024, 13, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casati, C.B.; Sánchez, V.; Baeza, R.; Magnani, N.; Evelson, P.; Zamora, M.C. Relationships between colour parameters, phenolic content and sensory changes of processed blueberry, elderberry and blackcurrant commercial juices. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, S.; Bulatović, M.; Zarić, D.; Kokeza, G.; Subić, J.; Rakin, M. Functional fermented whey carrot beverage-qualitative, nutritiveand techno-economic analysis. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 23, 13496–13504. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, M. Potential and differences of selected fermented non-alcoholic beverages. World Sci. News 2017, 72, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lupano, C.E. Effect of heat treatments in very acidic conditions on whey protein isolate properties. J. Dairy Sci. 1994, 77, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.N.; Vardhanabhuti, B.; Jaramillo, D.P.; Van Zanten, J.H.; Coupland, J.N.; Foegeding, E.A. Stability and mechanism of whey protein soluble aggregates thermally treated with salts. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 27, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.N.; Foegeding, E.A. Formation of soluble whey protein aggregates and their stability in beverages. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggy, A.K.; McManus, J.J.; Brodkorb, A.; Hogan, S.A.; Fenelon, M.A. Pilot-scale formation of whey protein aggregates determine the stability of heat-treated whey protein solutions—Effect of pH and protein concentration. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 10819–10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.K.; Shimelis, A.E.; Gesessew, K.L.; Agimassie, A.A.; Dessalegn, A.A. Formulation and evaluation of whey based ready-to-serve therapeutic beverage from Aloe debrana juice. Food Res. 2021, 5, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsaki, P.; Aspri, M.; Papademas, P. Novel Whey Fermented Beverage Enriched with a Mixture of Juice Concentrates: Evaluation of Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory (ACE) Activities Before and After Simulated Gastrointestinal Di-Gestion. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sanwal, N.; Bareen, M.A.; Barua, S.; Sharma, N.; Olatunji, O.J.; Nirmal, N.P.; Sahu, J.K. Trends in functional beverages: Functional ingredients, processing technologies, stability, health benefits, and consumer perspective. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messadi, N.; Mechmeche, M.; Setti, K.; Tizemmour, Z.; Hamdi, M.; Kachouri, F. Consumer perception of a new non-dairy functional beverage optimized made from lactic acid bacteria fermented date fruit extract. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnick, J.R.; Panthi, R.R.; Cenini, V.L.; Mishra, V.S.; O’Hagan, B.M.; Crowley, S.V.; O’Mahony, J.A. Rehydration Properties of Whey Protein Isolate Powders Containing Nanoparticulated Proteins. Dairy 2021, 2, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Whey Type | Processing Type | Type of Juice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cow’s milk whey (SKR) | Sweet whey (SS) | Unpasteurised (NP) | Apple juice (SJ) |

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Pasteurised (P) | Apple juice (SJ) | ||

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Sour whey (SK) | Unpasteurised (NP) | Apple juice (SJ) | |

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Pasteurised (P) | Apple juice (SJ) | ||

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Goat’s milk whey (SKZ) | Sweet whey (SS) | Unpasteurised (NP) | Apple juice (SJ) |

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Pasteurised (P) | Apple juice (SJ) | ||

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Sour whey (SK) | Unpasteurised (NP) | Apple juice (SJ) | |

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) | |||

| Pasteurised (P) | Apple juice (SJ) | ||

| Blackcurrant juice (SCP) | |||

| Kamchatka berry juice (SJK) |

| Fermented Drink | Apparent Viscosity [Pa s] ± SD | Dynamic Viscosity [mPas × g/cm3] ±SD | Apparent Viscosity [Pa s] ± SD | Dynamic Viscosity [mPas × g/cm3] ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Scale | Technical Scale | |||

| SKR/SS/NP/SJ | 0.2 a ± 0.02 | 19.33 b–g ± 1.25 | - | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/SCP | 1.17 ab ± 0.12 | 10.67 a–f ± 0.47 | 0.52 a ± 0.02 | 6.67 a–d ± 2.36 |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJK | 0.57 a ± 0.05 | 11.33 a–f ± 0.47 | - | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/K | 0.23 ab ± 0.05 | 17.33 a–g ± 1.70 | - | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJ | 0.10 a ± 0.00 | 21.33 c–h ± 1.70 | - | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SCP | 1.00 ab ± 0.29 | 32.00 g–j ± 2.45 | - | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJK | 0.37 a ± 0.17 | 5.00 a–c ± 0.82 | 0.33 a ± 0.14 | 6.67 a–d ± 2.36 |

| SKR/SS/P/K | 0.40 a ± 0.16 | 4.33 a–c ± 0.47 | 0.11 a ± 0,04 | 9.67 a–f ± 4.19 |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJ | 0.53 a ± 0.05 | 15.00 a–g ± 0.82 | - | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SCP | 1.30 ab ± 0.08 | 65.00 lm ± 4.08 | - | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJK | 1.20 ab ± 0.14 | 22.00 c–h ± 8.52 | 0.83 ab ± 0.25 | 46.67 j–l ± 4.71 |

| SKR/SK/NP/K | 0.30 a ± 0.00 | 11.67 a–f ± 1.25 | 0.31 a ± 0.17 | 95.67 n ± 4.19 |

| SKR/SK/P/SJ | 0.17 a ± 0.05 | 4.00 a–c ± 0.00 | - | - |

| SKR/SK/P/SCP | 2.10 ab ± 0.29 | 8.00 a–d ± 0.82 | 2.14 ab ± 0.28 | 8.00 a–d ± 4.24 |

| SKR/SK/P/SJK | 0.70 ab ± 0.24 | 4.67 a–c ± 0.94 | - | - |

| SKR/SK/P/K | 0.13 a ± 0.05 | 12.67 a–f ± 13.02 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJ | 0.27 a ± 0.09 | 38.33 h–k ± 2.36 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SCP | 0.80 ab ± 0.08 | 10.00 a–f ± 0.82 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJK | 0.37 a ± 0.05 | 81.67 mn ± 16.50 | 0.36 a ± 0.10 | 10.33 a–f ± 4.50 |

| SKZ/SS/NP/K | 0.93 ab ± 0.05 | 26.67 e–h ± 2.49 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJ | 0.23 a ± 0.19 | 4.00 a–c ± 0.00 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SCP | 0.90 ab ± 0.14 | 9.00 a–e ± 4.32 | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJK | 0.53 a ± 0.19 | 15.67 a–g ± 13.70 | 0.58 a ± 0.14 | 4.33 a–c ± 0.47 |

| SKZ/SS/P/K | 0.33 a ± 0.05 | 24.00 d–h ± 4.97 | - | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJ | 0.20 a ± 0.00 | 26.67 e–h ± 2.36 | - | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SCP | 1.37 ab ± 005 | 55.00 kl ± 16.33 | - | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJK | 0.73 ab ± 0.17 | 47.00 j–l ± 8l.64 | 0.53 a ± 0.08 | 11.67 a–f ± 4.71 |

| Fermented Drink | Storage Modulus (G′) [Pa] ±SD | Loss Modulus (G″) [Pa] ±SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Scale | Technical Scale | Laboratory Scale | Technical Scale | |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJ | 0.448 k ± 0.017 | - | 0.837 jk ± 0.058 | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/SCP | 0.152 e–g ± 0.032 | 0.165 fg ± 0.024 | 0.770 ij ± 0.029 | 0.767 ij ± 0.022 |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJK | 0.060 a–d ± 0.027 | - | 0.336 d ± 0.055 | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/K | 0.152 e–g ± 0.023 | - | 0.559 h ± 0.032 | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJ | 0.033 ab ± 0.014 | - | 0.296 b–d ± 0.056 | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SCP | 0.228 hi ± 0.024 | - | 0.883 k ± 0.045 | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJK | 0.051 a–c ± 0.013 | 0.193 gh ± 0.021 | 0.347 e ± 0.030 | 0.418 f ± 0.035 |

| SKR/SS/P/K | 0.066 a–d ± 0.030 | 0.034 ab ± 0.023 | 0.214 ab ± 0.022 | 0.277 b–d ± 0.027 |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJ | 0.038 ab ± 0.027 | - | 0.230 a–c ± 0.042 | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SCP | 0.209 g–i ± 0.035 | - | 0.783 b–d ± 0.023 | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJK | 0.070 a–d ± 0.024 | 0.344 jk ± 0.032 | 0.270 b–d ± 0.039 | 0.157 a ± 0.011 |

| SKR/SK/NP/K | 0.048 a–c ± 0.027 | 0.517 lm ± 0.013 | 0.267 b–d ± 0.033 | 1.270 m ± 0.046 |

| SKR/SK/P/SJ | 0.036 ab ± 0.018 | - | 0.262 b–d ± 0.028 | - |

| SKR/SK/P/SCP | 0.295 j ± 0.006 | 0.497 kl ± 0.018 | 1.774 p± 0.037 | 2.253 q ± 0.038 |

| SKR/SK/P/SJK | 0.025 a ± 0.013 | - | 0.281 b–d ± 0.028 | - |

| SKR/SK/P/K | 0.058 a–d ± 0.024 | - | 0.210 ab ± 0.026 | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJ | 0.028 a ± 0.023 | - | 0.314 cd ± 0.031 | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SCP | 0.117 d–f ± 0.023 | - | 0.697 i ± 0.035 | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJK | 0.023 a ± 0.010 | 0.040 ab ± 0.029 | 0.436 fg ± 0.031 | 0.340 d ± 0.025 |

| SKZ/SS/NP/K | 1.094 n ± 0.009 | - | 2.278 q ± 0.038 | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJ | 0.026 a ± 0.025 | - | 0.272 b–d ± 0.026 | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SCP | 0.109 c–f ± 0.014 | - | 0.550 h ± 0.033 | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJK | 0.029 a ± 0.027 | 0.049 a–c ± 0.020 | 0.313 cd ± 0.029 | 0.520 gh ± 0.029 |

| SKZ/SS/P/K | 0.191 gh ± 0.026 | - | 0.565 h ± 0.028 | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJ | 0.067 a–d ± 0.030 | - | 0.281 b–d ± 0.034 | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SCP | 0.262 ij ± 0.018 | - | 1.054 l ± 0.019 | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJK | 0.034 ab ± 0.022 | 0.056 a–d ± 0.035 | 0.451 fg ± 0.034 | 0.287 b–d ± 0.035 |

| SKZ/SK/NP/K | 0.097 b–e ± 0.021 | - | 0.437 fg ± 0.021 | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJ | 0.064 a–d ± 0.029 | - | 0.228 a–c ± 0.033 | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SCP | 0.575 m ± 0.016 | - | 1.508 o ± 0.044 | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJK | 0.042 ab ± 0.038 | 0.256 ij ± 0.028 | 0.290 b–d ± 0.038 | 0.698 i ± 0.036 |

| SKZ/SK/P/K | 0.062 a–d ± 0.035 | - | 0.150 a ± 0.039 | - |

| Fermented Drink | pH ±SD | Titratable Acidity [°SH] ±SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Scale | Technical Scale | Laboratory Scale | Technical Scale | |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJ | 4.45 s ± 0.01 | - | 18.8 a ± 0.2 | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/SCP | 3.12 a ± 0.00 | 3.13 ab ± 0.02 | -* | -* |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJK | 3.23 d–g ± 0.01 | - | - | - |

| SKR/SS/NP/K | 4.20 q ± 0.01 | - | 25 b–d ± 0,6 | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJ | 4.12 p ± 0.01 | - | 21 a–c ± 0 | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SCP | 3.13 ab ± 0.01 | - | - | - |

| SKR/SS/P/SJK | 3.27 gh ± 0.02 | 3.26 f–h ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKR/SS/P/K | 4.20 q ± 0.01 | 4.91 t ± 0.02 | 18.5 a ± 0.5 | 16.4 a ± 0.6 |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJ | 3.84 m ± 0.03 | - | 33.7 f ± 2.1 | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SCP | 3.18 cd ± 0.00 | - | - | - |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJK | 3.32 hi ± 0.03 | 3.37 i ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKR/SK/NP/K | 3.60 l ± 0.0 | 3.61 l ± 0.01 | 52.5 g ± 0.5 | 63.6 h ± 1 |

| SKR/SK/P/SJ | 3.99 o ± 0.01 | - | 30 d–f ± 1 | - |

| SKR/SK/P/SCP | 3.23 d–g ± 0.01 | 3.18 cd ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKR/SK/P/SJK | 3.45 j ± 0.00 | - | - | - |

| SKR/SK/P/K | 4.42 s ± 0.01 | - | 31.5 f ± 1.5 | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJ | 4.05 op ± 0.00 | - | 30.5 ef ± 0.5 | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SCP | 3.08 a ± 0.01 | - | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJK | 3.21 de ± 0.00 | 3.12 a ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKZ/SS/NP/K | 4.32 r ± 0.01 | - | 21 a–c ± 0 | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJ | 3.91 n ± 0.01 | - | 26 c–e ± 1 | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SCP | 3.10 a ± 0.01 | - | - | - |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJK | 3.22 d–g ± 0.01 | 3.12 a ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKZ/SS/P/K | 4.03 op ± 0.01 | - | 20.5 ab ± 0.5 | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJ | 3.53 k ± 0.03 | - | 71 i ± 1 | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SCP | 3.13 ab ± 0.00 | - | - | - |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJK | 3.23 d–g ± 0.01 | 3.21 de ± 0.04 | - | -* |

| SKZ/SK/NP/K | 3.61 l ± 0.01 | - | 76 i ± 1 | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJ | 3.54 k ± 0.01 | - | 59 h ± 1 | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SCP | 3.27 gh ± 0.00 | - | - | - |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJK | 3.27 gh ± 0.01 | 3.24 e–g ± 0.01 | - | -* |

| SKZ/SK/P/K | 3.61 l ± 0.00 | - | 51.7 g ± 0.7 | - |

| Fermented Drink | Tested Attribute | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance and Consistency | Colour | Smell | Taste | |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJ | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Cream and beige | Apple dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Apple-like, specific, no extraneous aftertaste |

| SKR/SS/NP/SCP | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/NP/SJK | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/NP/K | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Foreign odour indicative of spoilage product. | Taste evaluation was waived due to a perceptible foreign smell. |

| SKR/SS/P/SJ | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Beige | Apple dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Apple-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/P/SCP | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/P/K | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Creamy yellow | Specific, without extraneous odours. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJ | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Cream and beige | A perceptible foreign odour indicative of product spoilage. | Taste assessment was waived due to a perceptible foreign odour. |

| SKR/SK/NP/SCP | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Clear delamination of the product visible. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | A perceptible foreign aftertaste indicative of product spoilage. |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJK | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | A perceptible foreign aftertaste indicative of product spoilage. |

| SKR/SK/NP/K | Cloudy liquid, heterogeneous with lumps throughout. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Foreign odour indicative of spoilage product. | Taste assessment was waived due to a perceptible foreign odour. |

| SKR/SK/P/SJ | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Cream and beige | Apple dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Apple-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/P/SCP | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/P/SJK | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/P/K | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Creamy yellow | Specific, without extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJ | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Visible delamination of the product. | Cream and beige | Apple-like, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Apple-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SCP | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Currant-like, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJK | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Fine particles visible throughout, and a small precipitate at the bottom of the container. | Maroon with white particles | Berry, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/NP/K | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Specific, without extraneous aromas. | A specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJ | Cloudy liquid with visible sediment at the bottom of the pack. | Cream and beige | A specific apple flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A specific, apple-like flavour with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/P/SCP | Cloudy liquid with a slight visible precipitate at the bottom of the packaging. | Maroon | A distinctive, currant-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | Specific, currant-like flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | A specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/P/K | Cloudy fluid with visible stratification. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Specific, without extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJ | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Cream and beige | Apple-like, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Apple-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SCP | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Currant-like, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJK | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Throughout the volume, fine particles visible and a small deposit on the bottom of the packaging. | Maroon with white particles | Berry, peculiar, without extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/K | Cloudy liquid with gas bubbles. Small precipitate visible at the bottom of the pack. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Specific, with no extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJ | Cloudy liquid with a visible suspension on the surface and a slight sediment at the bottom of the container. | Cream and beige | A specific apple flavour with no extraneous aromas. | Specific, apple-like flavour with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/P/SCP | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | A distinctive, currant-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | Specific, currant-like flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | A specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/P/K | Cloudy liquid with a slight sediment at the bottom of the pack. | Creamy with a yellow tinge | Specific, with no extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| Fermented Drink | Tested Attribute | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance and Consistency | Colour | Smell | Taste | |

| SKR/SS/NP/SCP | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/NP/SJK | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Maroon | Berry dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Berry, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SK/P/SCP | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Maroon | Currant dominates, peculiar, with no extraneous aromas. | Currant-like, peculiar, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/NP/SJK | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Maroon | Specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SS/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with a small deposit visible at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/SJK | Cloudy liquid with visible sediment at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/P/SJK | Cloudy liquid with visible sediment at the bottom of the pack. | Maroon | Specific, berry-like flavour with no extraneous aromas. | A distinctive berry flavour, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKR/SS/P/K | Cloudy fluid with clear stratification visible. | Yellow and cream | Specific, without extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

| SKZ/SK/NP/K | Cloudy liquid with visible sediment at the bottom of the container. Fine particles visible throughout. | Creamy with a yellow tinge, with white particles | Specific, without extraneous aromas. | Specific, with no extraneous aftertaste. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szafrańska, J.O.; Waraczewski, R.; Bartoń, M.; Wesołowska-Trojanowska, M.; Sołowiej, B.G. Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensory Properties of Organic Goat’s and Cow’s Fermented Whey Beverages with Kamchatka Berry, Blackcurrant, and Apple Juices Produced at a Laboratory and Technical Scale. Foods 2026, 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010016

Szafrańska JO, Waraczewski R, Bartoń M, Wesołowska-Trojanowska M, Sołowiej BG. Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensory Properties of Organic Goat’s and Cow’s Fermented Whey Beverages with Kamchatka Berry, Blackcurrant, and Apple Juices Produced at a Laboratory and Technical Scale. Foods. 2026; 15(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzafrańska, Jagoda O., Robert Waraczewski, Maciej Bartoń, Marta Wesołowska-Trojanowska, and Bartosz G. Sołowiej. 2026. "Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensory Properties of Organic Goat’s and Cow’s Fermented Whey Beverages with Kamchatka Berry, Blackcurrant, and Apple Juices Produced at a Laboratory and Technical Scale" Foods 15, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010016

APA StyleSzafrańska, J. O., Waraczewski, R., Bartoń, M., Wesołowska-Trojanowska, M., & Sołowiej, B. G. (2026). Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensory Properties of Organic Goat’s and Cow’s Fermented Whey Beverages with Kamchatka Berry, Blackcurrant, and Apple Juices Produced at a Laboratory and Technical Scale. Foods, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010016