Development and Application of a Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR)-Based Isothermal Assay for Rapid Detection of Yak (Bos grunniens) Meat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Meat/Blood Samples

2.2. Extraction of Total DNA

2.3. Designing of Nucleotide Primers for Yak PSR

2.4. Yak PSR Assay Standardization

2.5. Detection and Confirmation of PSR Results Through Agarose Gel Separation and Fluorometric Analysis

2.6. Detection Limit and Selectivity Evaluation for PSR

2.7. Assessment of PSR Assay Reliability in Heat-Processed and Mixed Meat Mixtures

2.8. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DNA Quantity and Purity

3.2. Standardization of PSR Assay Parameters

3.2.1. Primer Dosage

3.2.2. Magnesium Sulphate (MgSO4) Dosage

3.2.3. Deoxynucleotide Triphosphates (dNTPs) Dosage

3.2.4. Betaine Dosage

3.2.5. Bst DNA Polymerase Dosage

3.2.6. Reaction Time and Temperature

3.3. Assessment of PSR Assay Sensitivity and Selectivity Parameters

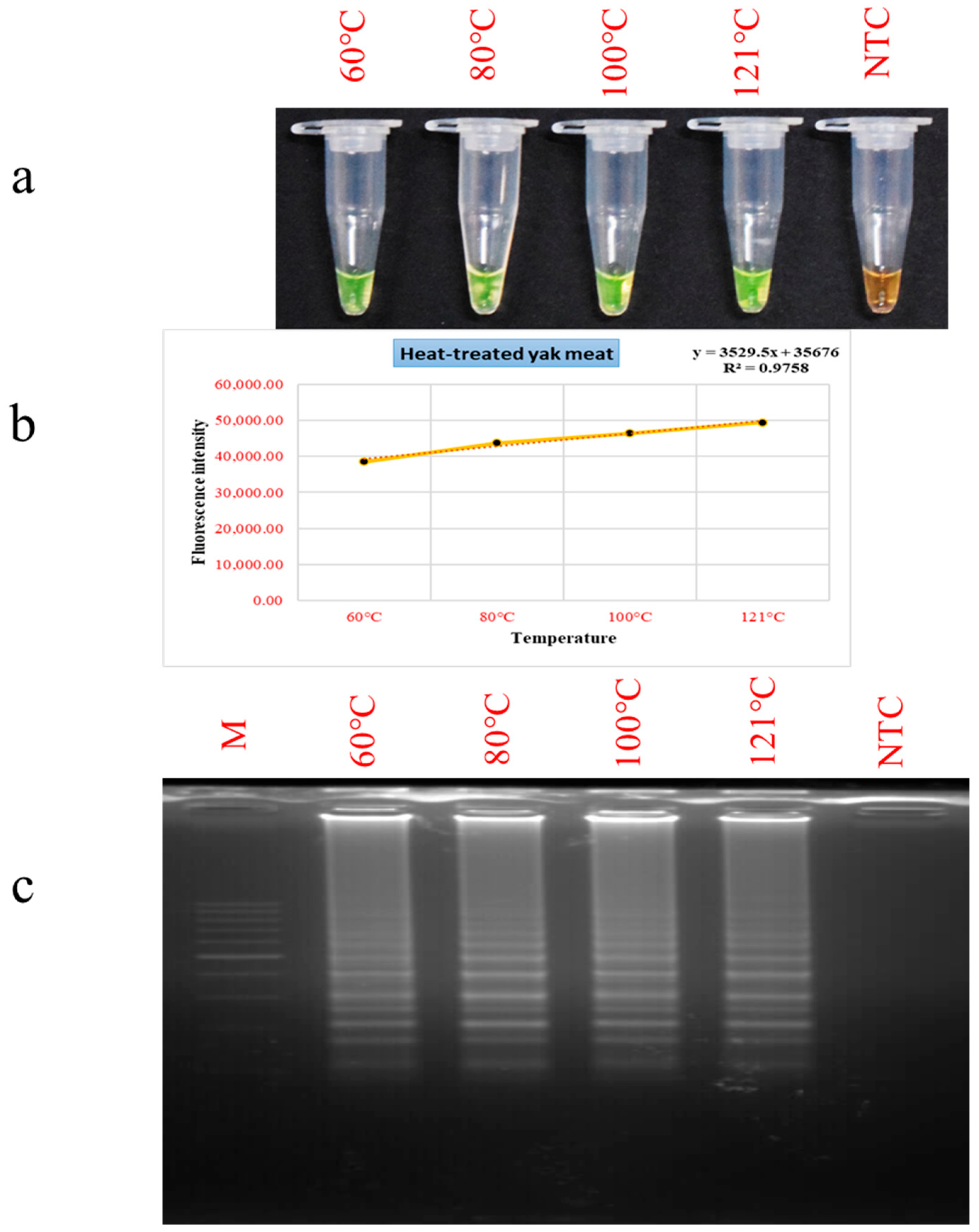

3.4. Evaluation of PSR Performance in Thermally Processed Meat Matrices

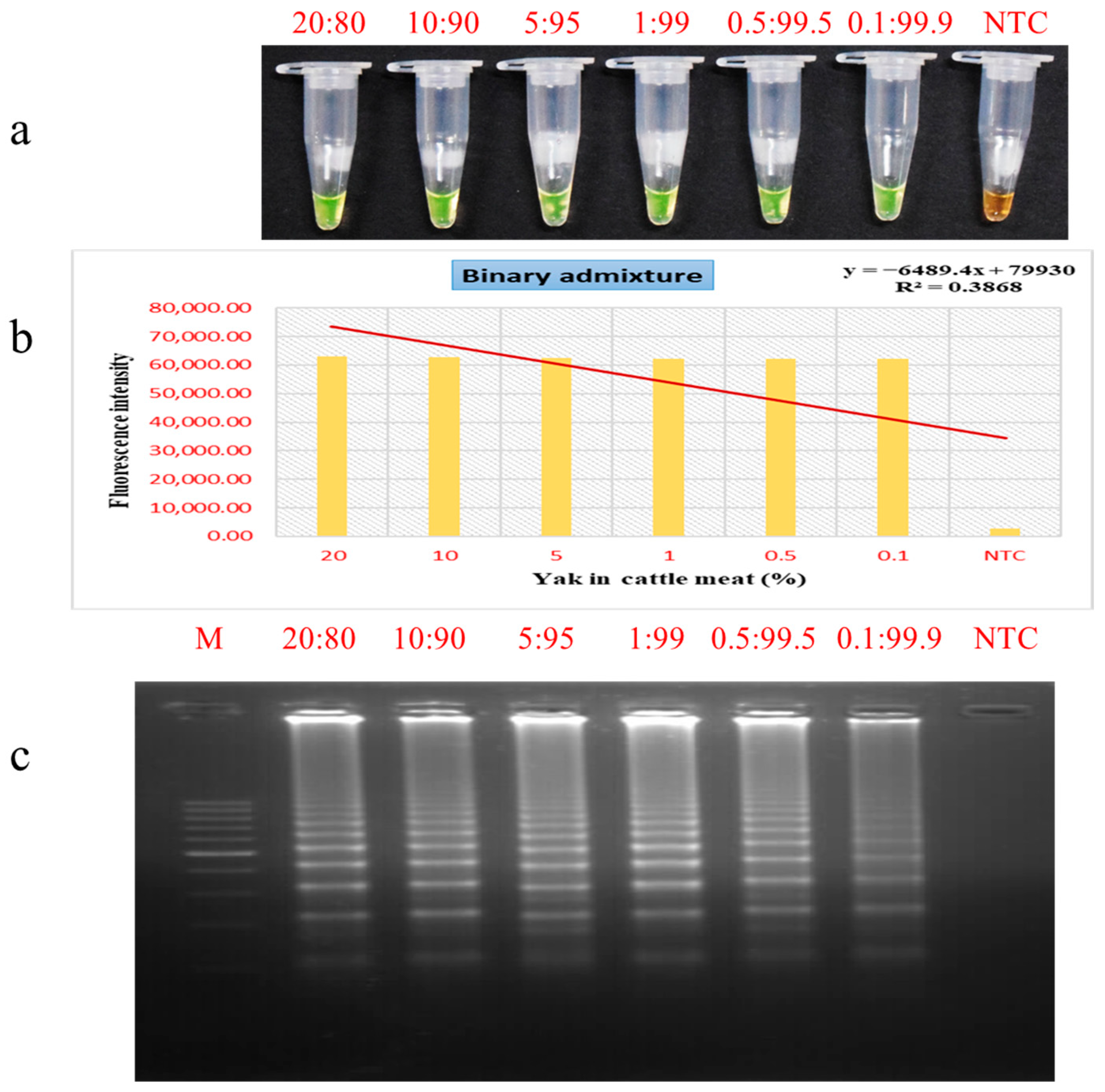

3.5. Evaluation of PSR Assay for Meat Admixture Detection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cavin, C.; Cottenet, G.; Cooper, K.M.; Zbinden, P. Meat vulnerabilities to economic food adulteration require new analytical solutions. Chimia 2018, 72, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mech, M.M.; Rathore, H.S.; Jawla, J.; Karabasanavar, N.; Hanah, S.S.; Kumar, H.; Ramesh, V.; Milton, A.A.P.; Vidyarthi, V.K.; Sarkar, M.; et al. Development of Rapid Alkaline Lysis–Polymerase Chain Reaction Technique for Authentication of Mithun (Bos frontalis) and Yak (Bos grunniens) Species. Molecules 2025, 30, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shears, P. Food fraud—A current issue but an old problem. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, P.S.; Priyanka, D.; Bhaskar, R.V.; Sudheer, K.; Vikram, R.; Jyoti, J.; Raveendhar, N.; Ramakrishna, C.; Barbuddhe, S.B. Portable Meat Production and Retailing Facility (P-MART): A novel technology for clean meat production from sheep and goats. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2025, 65, AN24351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mech, M.M.; Rathore, H.S.; Milton, A.A.P.; Karabasanavar, N.; Srinivas, K.; Khan, S.; Hussain, Z.; Ramesh, V.; Kumar, H.; Das, S.; et al. Development of a visual assay for Mithun (Bos frontalis) meat authentication using polymerase spiral reaction (PSR). Food Control 2026, 179, 111576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, M.; Kumar, H.; Saravanan, K.A.; Rajawat, D.; Sonejita Nayak, S.; Ghildiyal, K.; Kaisa, K.; Parida, S.; Bhushan, B.; Dutt, T. Trajectory of livestock genomics in South Asia: A comprehensive review. Gene 2022, 843, 146808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Y. Understanding Consumer Preferences for Attributes of Yak Meat: Implications for Economic Growth and Resource Efficiency in Pastoral Areas. Meat Sci. 2024, 216, 109586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Huang, J.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Pang, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y. Development of dual polymerase spiral reaction for detection of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus simultaneously. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 430, 111055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, A.; You, X.; Zhao, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, L.; Yang, S. Identification of meat from yak and cattle using SNP markers with integrated allele-specific polymerase chain reaction–capillary electrophoresis method. Meat Sci. 2019, 148, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, A. Microsatellite markers for animal identification and meat traceability of six beef cattle breeds in the Chinese market. Food Control 2017, 78, 469−475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.R.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.Y.; Jiang, L.; Tian, M.; Ren, F.Z. Detection of cow milk adulteration in yak milk by ELISA. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 6000–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, D. Differences in proteomic profiles of milk fat globule membrane in yak and cow milk. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1822–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minoudi, S.; Gkagkavouzis, K.; Karaiskou, N.; Lazou, T.; Triantafyllidis, A. DNA-based authentication in meat products: Quantitative detection of species adulteration and compliance issues. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dule, E.J.; Kinimi, E.; Bakari, G.G.; Max, R.A.; Lyimo, C.M.; Mushi, J.R. Species authentication in meat products sold in Kilosa District in Tanzania using HRM-enhanced DNA barcoding. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2025, 20, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.A.; Vishnuraj, M.R.; Vaithiyanathan, S.; Srinivas, C.; Chauhan, A.; Pothireddy, N.; Uday Kumar Reddy, T.; Barbuddhe, S.B. First report on ddPCR-based regression models for quantifying buffalo substitution in “Haleem”—A traditional meat delicacy. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Han, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y. DNA-based authentication method for detection of yak (Bos grunniens) in meat products. J. AOAC Int. 2013, 96, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zeng, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Tang, X. RPA-Cas12a-FS: A frontline nucleic acid rapid detection system for food safety based on CRISPR-Cas12a combined with recombinase polymerase amplification. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glökler, J.; Lim, T.S.; Ida, J.; Frohme, M. Isothermal amplifications—A comprehensive review on current methods. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 56, 543–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T.; Okayama, H.; Masubuchi, H.; Yonekawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Amino, N.; Hase, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizardi, P.M.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Bray-Ward, P.; Thomas, D.C.; Ward, D.C. Mutation detection and single-molecule counting using isothermal rolling-circle amplification. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Xu, Y.; Kong, H. Helicase-dependent isothermal DNA amplification. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Mao, Y.; Soteyome, T.; Liu, G.; Seneviratne, G.; Kjellerup, B.V.; Xu, Z. Development and application of multiple polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) assays for rapid detection of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and toxins from rice and flour products. LWT 2023, 173, 114287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, N.; Maan, S. Novel Isothermal Reverse Transcription Polymerase Spiral Reaction (RT-PSR) Assay for the Detection of Newcastle Disease Virus in Avian Species. Indian J. Microbiol. 2024, 65, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, A.A.P.; Momin, K.M.; Ghatak, S.; Priya, G.B.; Angappan, M.; Das, S.; Puro, K.; Sanjukta, R.K.; Shakuntala, I.; Sen, A.; et al. Development of a novel polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) assay for rapid and visual detection of Clostridium perfringens in meat. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, B.L.; Girish, P.S.; Karabasanavar, N.; Reddy, S.S.; Basode, V.K.; Priyanka, D.; Sankeerthi, P.; Vasanthi, J. Development and validation of isothermal polymerase spiral reaction assay for the specific authentication of goat (Capra hircus) meat. Food Control 2023, 151, 109811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danawadkar, V.N.; Ruban, S.W.; Milton, A.A.P.; Kiran, M.; Momin, K.M.; Ghatak, S.; Mohan, H.V.; Porteen, K. Development of novel isothermal-based DNA amplification assay for detection of pig tissues in adulterated meat. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawla, J.; Chatli, M.K. A rapid and field-ready snap-chill polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) colorimetric assay for identification of buffalo (Bubalus bubalus) tissue. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawla, J.; Chatli, M.K.; Vikram, R.; Pipaliya, G.; Kumar, D.; Somagond, Y.M.; Narendra, V.N.; Fular, A. Real-time monitoring of cattle (Bos taurus) tissue using a novel point-of-care (POC) polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) colorimetric assay. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 136, 106773. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.H.; Bai, W.L.; Wang, J.M.; Wu, C.D.; Dou, Q.L.; Yin, R.L.; He, J.B.; Luo, G.B. Development of an assay for rapid identification of meat from yak and cattle using polymerase chain reaction technique. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, K.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Murphy, R.W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. DNA barcoding reveals commercial fraud related to yak jerky sold in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2016, 59, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.P.; Kalita, D.J.; Borah, P.; Sarma, S.; Dutta, R.; Rajkhowa, D. Molecular characterization of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene of cattle, buffalo and yak. Vet. Arh. 2016, 86, 777–785. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Shen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhong, R.; Raza, S.H.A.; Zhong, Q.; Lei, H. Duplex recombinase polymerase amplification combined with CRISPR/Cas12a-Cas12a assay for on-site identification of yak meat adulteration. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 134, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhuang, P.; Cheng, W.; Brennan, C.S.; Yin, Z. The Identification of Yak Meat Using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Method Coupled with Hydroxy Naphthol Blue for the Prevention of Food Fraud. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2024, 2024, 6549138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.C.B.; Milton, A.A.P.; Menon, V.K.; Srinivas, K.; Bhargavi, D.; Das, S.; Ghatak, S.; Vineesha, S.L.; Sunil, B.; Latha, C.; et al. Development of a novel visual assay for ultrasensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk and chicken meat harnessing helix loop-mediated isothermal amplification (HAMP). Food Control 2024, 155, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, P.S.; Haunshi, S.; Vaithiyanathan, S.; Rajitha, R.; Ramakrishna, C. A rapid method for authentication of Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) meat by Alkaline Lysis method of DNA extraction and species-specific polymerase chain reaction. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, M.; Honda, E.; Ogura, A.; Nomoto, A.; Hanaki, K.I. Colorimetric detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by using hydroxyl naphthol blue. Biotechniques 2009, 46, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, P.S.; Barbuddhe, S.B.; Kumari, A.; Rawool, D.B.; Karabasanavar, N.S.; Muthukumar, M.; Vaithiyanathan, S. Rapid detection of pork using alkaline lysis- Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (AL-LAMP) technique. Food Control 2020, 110, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, P.S.; Kumari, A.; Gireesh-Babu, P.; Karabasanavar, N.S.; Raja, B.; Ramakrishna, C.; Barbuddhe, S.B. Alkaline lysis-loop mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and on-site authentication of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) meat. J. Food Saf. 2022, 42, e12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounika, T.; Girish, P.S.; Shashi Kumar, M.; Kumari, A.; Singh, S.; Karabasanavar, N.S. Identification of sheep (Ovis aries) meat by alkaline lysis-loop mediated isothermal amplification technique targeting mitochondrial D-loop region. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 3825–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, C.; Xie, P.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Xian, Y.; Lei, H.; Shen, X. Alkaline lysis-recombinase polymerase amplification combined with CRISPR/Cas12a assay for the ultrafast visual identification of pork in meat products. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Gao, J.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, C.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G. Establishment and application of polymerase spiral reaction amplification for Salmonella detection in food. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawla, J.; Kumar, R.R.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Agarwal, R.K.; Singh, P.; Saxena, V.; Kumari, S.; Boby, N.; Kumar, D.; Rana, P. On-site paper-based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification coupled Lateral Flow Assay for pig tissue identification targeting mitochondrial COI gene. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Son, J.; Kim, D.; Cha, B.S.; Lee, E.S.; Park, K.S. Low-Temperature Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Operating at Physiological Temperature. Biosensors 2023, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, A.A.P.; Momin, K.M.; Ghatak, S.; Thomas, S.C.; Priya, G.B.; Angappan, M.; Das, S.; Sanjukta, R.K.; Puro, K.; Shakuntala, I.; et al. Development of a novel polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) assay for rapid and visual detection of Staphylococcus aureus in meat. LWT 2021, 139, 110507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, A.A.P.; Momin, K.M.; Priya, G.B.; Das, S.; Angappan, M.; Sen, A.; Sinha, D.K.; Ghatak, S. Development of a novel visual detection technique for Campylobacter jejuni in chicken meat and caecum using polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) with pre-added dye. Food Control 2021, 126, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zou, D.; He, X.; Ao, D.; Su, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, Y.; Ma, W.; et al. Development and application of a rapid Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection technique using polymerase spiral reaction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, K.M.; Milton, A.A.P.; Ghatak, S.; Thomas, S.C.; Priya, G.B.; Das, S.; Shakuntala, I.; Sanjukta, R.; Puro, K.-u.; Sen, A. Development of a novel and rapid polymerase spiral reaction (PSR) assay to detect Salmonella in pork and pork products. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 50, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, N.; Mori, Y.; Kanda, H.; Notomi, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, K.H. Optimization and troubleshooting in PCR. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, 4, pdb.ip66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.A.; Fukushima, M.; Davis, R.W. DMSO and betaine greatly improve amplification of GC-rich constructs in de novo synthesis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- En, F.X.; Wei, X.; Jian, L.; Qin, C. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification establishment for detection of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 151, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, J.A. Structural and catalytic chemistry of magnesium-dependent enzymes. BioMetals 2002, 15, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chakravarti, S.; Chander, V.; Majumder, S.; Bhat, S.A.; Gupta, V.K.; Nandi, S. Polymerase spiral reaction (PSR): A novel, visual isothermal amplification method for detection of canine parvovirus 2 genomic DNA. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, J.A.; Chakravarti, S.; Gupta, V.; Chander, V.; Sharma, G.K.; Qureshi, S.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, V.K.; Nandi, S. Novel Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR) for rapid visual detection of Bovine Herpesvirus 1 genomic DNA from aborted bovine fetus and semen. Gene 2018, 644, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zuo, K.; Li, Z.; Leng, C.; Kan, Y.; Yao, L.; Bi, Y. Novel polymerase spiral reaction assay for the visible molecular detection of porcine circovirus type 3. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dai, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y. Rapid and visual detection of Listeria monocytogenes based on polymerase spiral reaction in fresh-cut fruit. LWT 2024, 197, 115909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Soto, P.; Mvoulouga, P.O.; Akue, J.P.; Abán, J.L.; Santiago, B.V.; Sánchez, M.C.; Muro, A. Development of a highly sensitive Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) method for the detection of Loa loa. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Kumar, R.R.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, D.; Rana, P.; Jawla, J. On-Site Detection of Tissues of Buffalo Origin by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay Targeting Mitochondrial Gene Sequences. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musto, M. DNA quality and integrity of nuclear and mitochondrial sequences from beef meat as affected by different cooking methods. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2011, 49, 525–528. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, A.R.; Dong, H.J.; Cho, S. Meat species identification using loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay targeting species-specific mitochondrial DNA. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2014, 34, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Xiang, J.; Fu, Q.; Sun, X.; Liu, L.; Ai, L.; Wang, J. Rapid detection of duck ingredient in adulterated foods by isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification assays. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2023, 6, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nischala, S.; Vaithiyanathan, S.; Ashok, V.; Kalyani, P.; Srinivas, C.; Aravind Kumar, N.; Vishnuraj, M.R. Development of a Touchdown—Duplex PCR Assay for Authentication of Sheep and Goat Meat. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, P.A.; Strydom, P.E.; Webb, E.C.; De Kock, H.L. Meat quality of designated South African indigenous goat and sheep breeds. Meat Sci. 2003, 65, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, R.R.; Rana, P.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Agarwal, R.K.; Singh, P.; Kumari, S.; Jawla, J. On point identification of species origin of food animals by recombinase polymerase amplification-lateral flow (RPA-LF) assay targeting mitochondrial gene sequences. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Rapid visual detection of eight meat species using optical thin-film biosensor chips. J. AOAC Int. 2015, 98, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Technique | Oligonucleotide Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-loop | PCR-F | TAAATGTAAAGAGCCTCACCAGTA | 422 bp | [2] |

| PCR-R | ATTAAATAGCGACCCCCACAGTTC | |||

| PSR-F | acgattcgtacatagaagtatagTAAATGTAAAGAGCCTCACCAGTA | variable | ||

| PSR-R | gatatgaagatacatgcttagcaATTAAATAGCGACCCCCACAGTTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mech, M.M.; Rathore, H.S.; Milton, A.A.P.; Karabasanavar, N.; Hanah, S.S.; Srinivas, K.; Khan, S.; Hussain, Z.; Kumar, H.; Ramesh, V.; et al. Development and Application of a Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR)-Based Isothermal Assay for Rapid Detection of Yak (Bos grunniens) Meat. Foods 2026, 15, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010115

Mech MM, Rathore HS, Milton AAP, Karabasanavar N, Hanah SS, Srinivas K, Khan S, Hussain Z, Kumar H, Ramesh V, et al. Development and Application of a Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR)-Based Isothermal Assay for Rapid Detection of Yak (Bos grunniens) Meat. Foods. 2026; 15(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleMech, Moon Moon, Hanumant Singh Rathore, Arockiasamy Arun Prince Milton, Nagappa Karabasanavar, Sapunii Stephen Hanah, Kandhan Srinivas, Sabia Khan, Zakir Hussain, Harshit Kumar, Vikram Ramesh, and et al. 2026. "Development and Application of a Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR)-Based Isothermal Assay for Rapid Detection of Yak (Bos grunniens) Meat" Foods 15, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010115

APA StyleMech, M. M., Rathore, H. S., Milton, A. A. P., Karabasanavar, N., Hanah, S. S., Srinivas, K., Khan, S., Hussain, Z., Kumar, H., Ramesh, V., Das, S., Ghatak, S., Loat, S., Pukhrambam, M., Vidyarthi, V. K., Sarkar, M., & Shivanagowda, G. P. (2026). Development and Application of a Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR)-Based Isothermal Assay for Rapid Detection of Yak (Bos grunniens) Meat. Foods, 15(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010115