Processing-Induced Changes in Phenolic Composition and Dough Properties of Grape Pomace-Enriched Wheat Buns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Basic Chemical Analyses of Grape Pomace

2.3. Rheological Analysis of Wheat Flour Substituted with Grape Pomace

2.4. Analysis of the Phenolic Compounds

2.4.1. Reference Standards for Phenolic Compounds and Reagents

2.4.2. Phenolic and Internal Standards Preparation and Sample Extraction

2.4.3. UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS Instrumentation and Analysis

2.5. Wheat Bun Preparation, Sampling, Shape and Physical Analyses

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Polyphenol Composition in Starting Materials

3.2. Changes in Phenolic Compound Content During Bakery Processing with Grape Pomace Addition

Dominant Free Phenolic Compounds of Grape Pomace and Their Changes During Bakery Processing

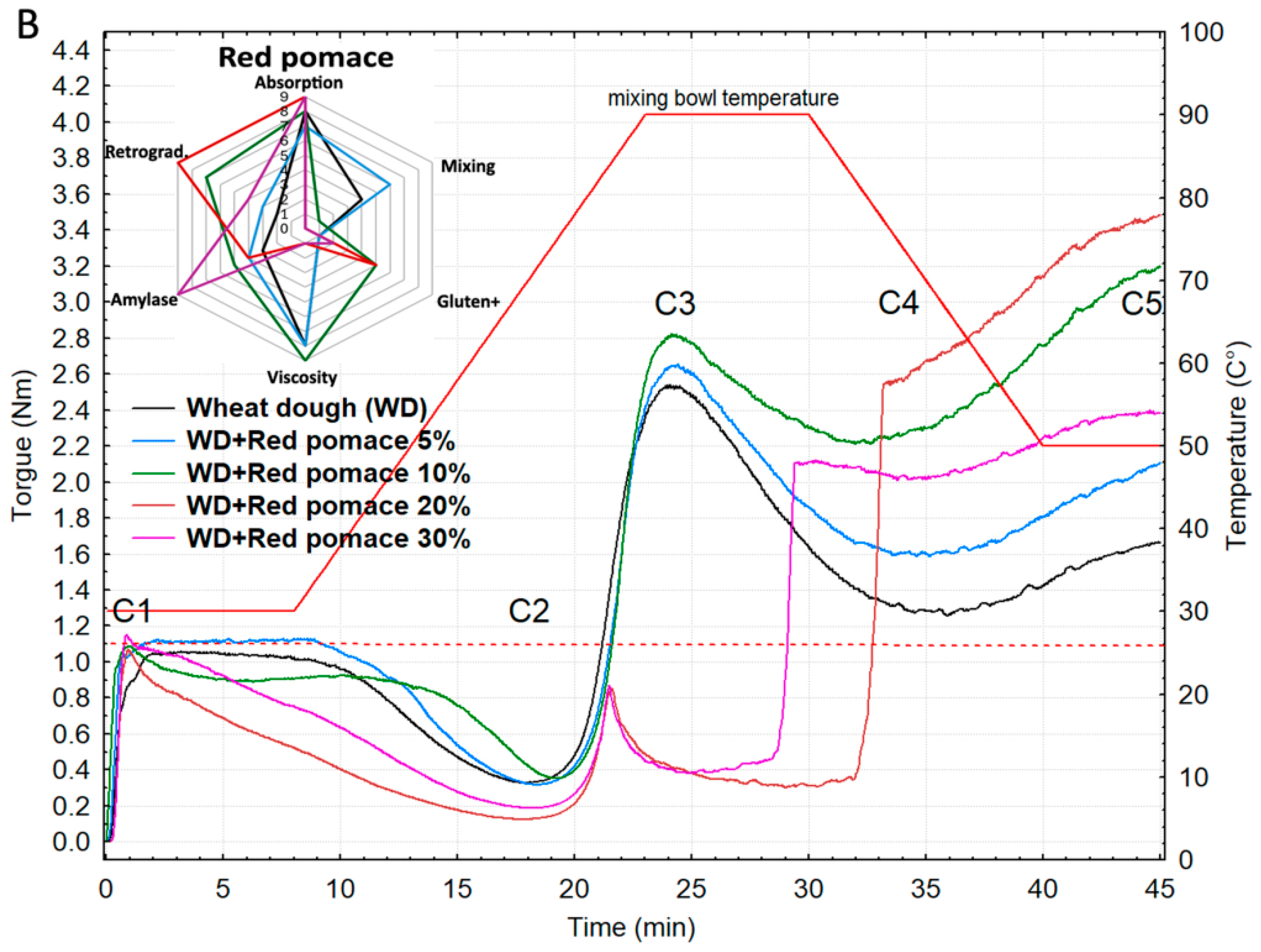

3.3. Rheological Behavior of Wheat Flour Supplemented with Grape Pomace

Shape and Physical Profiles of Wheat Buns Containing Grape Pomace

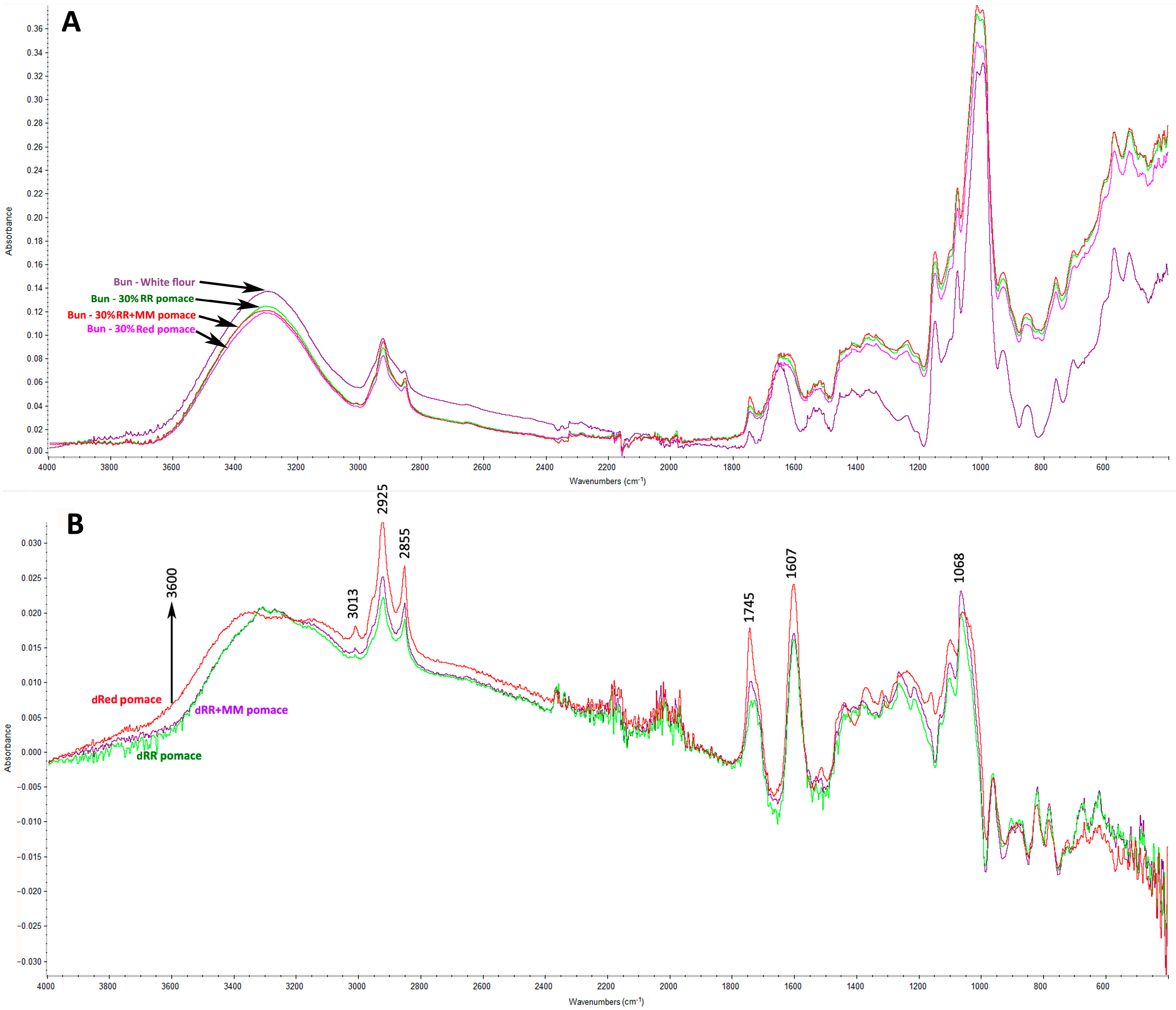

3.4. Interactions of Phenolic Compounds from Grape Pomace with Proteins and Starch in Wheat Buns

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakov, G.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Ivanova, N.; Stamatovska, V.; Dimov, I. Effect of grape pomace powder addition on chemical, nutritional and technological properties of cakes. LWT 2020, 134, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawi, A.H. Enriching wheat flour with grape pomace powder impacts a snack’s chemical, nutritional, and sensory characteristics. Czech J. Food Sci. 2024, 42, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardi, C.; D’Amico, L.; Durante, M.; Tufariello, M.; Giovinazzo, G. Whole grape pomace flour as nutritive ingredient for enriched durum wheat pasta with bioactive potential. Foods 2023, 12, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troilo, M.; Difonzo, G.; Paradiso, V.M.; Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F. Grape pomace as innovative flour for the formulation of functional muffins: How particle size affects the nutritional, textural and sensory properties. Foods 2022, 11, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, S.; Delsart, C.; Vitrac, X.; Peuchot, M.M.; Ghidossi, R. Characterisation of polyphenols and antioxidant potential of red and white pomace by-product extracts using subcritical water extraction. OENO One 2020, 54, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelenein, D.; Mustafa, A.M.; Caprioli, G.; Ricciutelli, M.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S. Phenolic and nutritional profiles, and antioxidant activity of grape pomaces and seeds from Lacrima di Morro d’Alba and Verdicchio varieties. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; García-Pérez, P.; Martinelli, E.; Giuberti, G.; Trevisan, M.; Lucini, L. Different fractions from wheat flour provide distinctive phenolic profiles and different bioaccessibility of polyphenols following in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arfaoui, L. Dietary plant polyphenols: Effects of food processing on their content and bioavailability. Molecules 2021, 26, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrajda-Brdak, M.; Konopka, I.; Tańska, M.; Czaplicki, S. Changes in the content of free phenolic acids and antioxidative capacity of wholemeal bread in relation to cereal species and fermentation type. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2247–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bautista, M.; Gutiérrez, T.J.; Tovar, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Effect of starch structuring and processing on the bioaccessibility of polyphenols in starchy foodstuffs: A review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Fan, G. A systematic review of recent advances in anthocyanin-biomacromolecule interactions and their applications in the food industry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 2553–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Banerjee, K. Wheat flour replacement by wine grape pomace powder positively affects physical, functional and sensory properties of cookies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India B Biol. Sci. 2017, 87, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5983-1:2005; Animal feeding stuffs—Determination of nitrogen content and calculation of crude protein content—Part 1: Kjeldahl Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- AOAC INTERNATIONAL. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL. In Method 920.39: Fat (Crude) in Animal Feed and Agricultural Products, 22nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěrbová, L.; Bradová, J.; Sedláček, T.; Holasová, M.; Fiedlerová, V.; Dvořáček, V.; Smrčková, P. Influence of technological processing of wheat grain on starch digestibility and resistant starch content. Starch-Stärke 2016, 68, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICC Standard No. 173; Determination of Rheological Behavior of Wheat Flour Dough Using the Mixolab. International Association for Cereal Science and Technology (ICC): Vienna, Austria, 2006.

- Torbica, A.; Drašković, M.; Tomić, J.; Dodig, D.; Bošković, J.; Zečević, V. Utilization of Mixolab for assessment of durum wheat quality dependent on climatic factors. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 69, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jágr, M.; Hofinger-Horvath, A.; Ergang, P.; Čepková, P.H.; Schönlechner, R.; Pichler, E.C.; D Amico, S.; Grausgruber, H.; Vagnerová, K.; Dvořáček, V. Comprehensive study of the effect of oat grain germination on the content of avenanthramides. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACCI Approved Method 10-05.01; Guidelines for Rheological Testing of Wheat Flour Dough Using the Mixolab. AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009.

- Babicki, S.; Arndt, D.; Marcu, A.; Liang, Y.; Grant, J.R.; Maciejewski, A.; Wishart, D.S. Heatmapper: Web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W147–W153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Giuberti, G.; Lucini, L.; Simonato, B. Impact of grape pomace powder on the phenolic bioaccessibility and on in vitro starch digestibility of wheat based bread. Foods 2021, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, C.M.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Pinho, S.P.; Ferreira, I.C. Grape pomace as a source of phenolic compounds and diverse bioactive properties. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalangre, A.; Mirza, A.; Chavan, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Shaikh, N.; TP, A.S. Drying and degradation kinetics of red grape pomace with special emphasis on degradation of anthocyanins using liquid chromatography-orbitrap-mass spectrometry. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, G.; Tilley, M.; Li, Y. Changes in phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities during the whole wheat bread-making process. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aal, E.S.M.; Rabalski, I. Changes in phenolic acids and antioxidant properties during baking of bread and muffin made from blends of hairless canary seed, wheat, and corn. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, J.V.; Esteban-Muñoz, A.; Fernández-Espinar, M.T. Changes in the Polyphenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Wheat Bread after Incorporating Quinoa Flour. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Nataliya, G. Rheological, pasting and sensory properties of biscuits supplemented with grape pomace powder. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, e78421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolve, R.; Simonato, B.; Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Giuberti, G. Wheat bread fortification by grape pomace powder: Nutritional, technological, antioxidant, and sensory properties. Foods 2021, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinei, M.; Oroian, M. The Potential of Grape Pomace Varieties as a Dietary Source of Pectic Substances. Foods 2021, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Cai, Y.Z.; Sun, M.; Corke, H. Effect of phenolic compounds on the pasting and textural properties of wheat starch. Starch-Stärke 2008, 60, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, C.; Debonne, E.; Versele, S.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Eeckhout, M. Technological evaluation of fiber effects in wheat-based dough and bread. Foods 2024, 13, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhou, P.; Bao, Q.; Wang, X. Effect of wheat bran dietary fibre on the rheological properties of dough during fermentation and Chinese steamed bread quality. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, S.; Oest, M.; Rohn, S. Interactions between phenolic acids, proteins, and carbohydrates—Influence on dough and bread properties. Foods 2021, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šporin, M.; Avbelj, M.; Kovač, B.; Možina, S.S. Quality characteristics of wheat flour dough and bread containing grape pomace flour. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Hamzah, N.H.; Khairuddin, N.; Muhamad, I.I.; Hassan, M.A.; Ngaini, Z.; Sarbini, S.R. Characterisation and colour response of smart sago starch-based packaging films incorporated with Brassica oleracea anthocyanin. Membranes 2022, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandarabadi, S.M.; Mahmoudian, M.; Farah, K.R.; Abdali, A.; Nozad, E.; Enayati, M. Active intelligent packaging film based on ethylene vinyl acetate nanocomposite containing extracted anthocyanin, rosemary extract and ZnO/Fe-MMT nanoparticles. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 22, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majaliwa, N.; Kibazohi, O.; Alminger, M. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Probing on Interactions of Proteins with Phenolic Compounds in the East African Highland Banana Pulp at Different Stages of Banana Juice Extraction. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev. 2025, 34, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welc-Stanowska, R.; Kłosok, K.; Nawrocka, A. Effects of gluten-phenolic acids interaction on the gluten structure and functional properties of gluten and phenolic acids. J. Cereal Sci. 2023, 111, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.D.; Chalimah, S.; Primadona, I.; Hanantyo, M.H.G. Physical and chemical properties of corn, cassava, and potato starchs. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 160, p. 012003. [Google Scholar]

- Durmus, Y.; Whitney, K.; Anil, M.; Simsek, S. Enrichment of sourdough bread with hazelnut skin, cross-linked starch, or oxidized starch for improvement of nutritional quality. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Elemental Composition | Polarity | NCE * | Rt (min) | Precursor ion (m/z) | Quantification ion (m/z) | Confirmation ion (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astilbin | C21H22O11 | negative | 20 | 8.90 | 449.1089 | 151.0026 | 285.0404 |

| Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | negative | 40 | 6.40 | 179.0350 | 135.0439 | 117.0334 |

| Catechin | C15H14O6 | negative | 30 | 5.38 | 289.0718 | 245.0814 | 109.0281 |

| Catechin gallate | C22H18O10 | negative | 20 | 7.93 | 441.0828 | 169.0132 | 289.0708 |

| Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | positive | 20 | 5.94 | 355.1024 | 163.0389 | 145.0281 |

| Cis-resveratrol | C8H8O3 | positive | 32 | 10.45 | 229.0859 | 135.0441 | 119.0499 |

| Delphinidine-3-O-galactoside | C21H20O12 | positive | 30 | 6.12 | 465.1028 | 303.0487 | 257.0443 |

| Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | negative | 30 | 6.66 | 289.0718 | 245.0814 | 109.0281 |

| Epicatechin gallate | C22H18O10 | negative | 20 | 7.54 | 441.0828 | 169.0132 | 289.0708 |

| Epigallocatechin | C15H14O7 | negative | 35 | 5.18 | 305.0667 | 125.0232 | 219.0656 |

| Epigallocatechin gallate | C22H18O11 | negative | 20 | 6.24 | 457.0771 | 169.0132 | 305.0663 |

| Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | positive | 45 | 8.23 | 195.0643 | 177.0545 | 145.0283 |

| Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | negative | 45 | 2.76 | 169.0123 | 125.0232 | 97.0282 |

| Gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | negative | 35 | 3.80 | 305.0667 | 125.0232 | 167.0340 |

| Gallocatechin gallate | C22H18O11 | negative | 20 | 6.89 | 457.0771 | 169.0132 | 305.0663 |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | negative | 60 | 5.46 | 137.0244 | 93.0332 | 65.0383 |

| Hyperoside | C21H20O12 | negative | 30 | 9.23 | 463.0882 | 300.0267 | 271.0244 |

| Isoquercetin | C21H20O12 | negative | 30 | 9.31 | 463.0882 | 300.0267 | 271.0244 |

| Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | negative | 70 | 12.20 | 285.0405 | 185.0598 | 93.0332 |

| Malvidine-3-O-galactoside | C23H24O12 | positive | 20 | 7.54 | 493.1341 | 331.0799 | 315.0496 |

| Miquelianin | C21H18O13 | positive | 15 | 9.19 | 479.0820 | 303.0498 | 229.0495 |

| Myricetin | C15H10O8 | negative | 40 | 9.95 | 317.0303 | 151.0025 | 178.9977 |

| Neochlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | positive | 20 | 4.63 | 355.1024 | 163.0389 | 145.0281 |

| Petunidine-3-O-glucoside | C22H22O12 | positive | 20 | 6.92 | 479.1184 | 317.0659 | 302.0425 |

| Probenecid (intern. standard) | C13H19NO4S | negative | 30 | 12.39 | 284.0957 | 198.0584 | 240.1057 |

| Procyanidine A2 | C30H24O12 | positive | 10 | 7.73 | 577.1341 | 425.0858 | 287.0540 |

| Procyanidine B1 | C30H26O12 | positive | 20 | 4.73 | 579.1497 | 127.0389 | 409.0907 |

| Procyanidine B2 | C30H26O12 | positive | 20 | 5.71 | 579.1497 | 127.0389 | 409.0907 |

| Procyanidine B3 | C30H26O12 | positive | 20 | 4.65 | 579.1497 | 127.0389 | 409.0907 |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | negative | 40 | 11.21 | 301.0354 | 151.0024 | 178.9975 |

| Quercitrin | C21H20O11 | negative | 30 | 10.12 | 447.0933 | 300.0270 | 271.0239 |

| Rutin | C27H30O16 | negative | 40 | 9.28 | 609.1461 | 300.0267 | 271.0241 |

| Syringic acid | C9H60O5 | positive | 30 | 6.89 | 199.0596 | 140.0465 | 155.0700 |

| Taxifolin | C15H12O7 | positive | 20 | 8.01 | 305.0656 | 259.0596 | 153.0180 |

| trans-p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | negative | 10 | 7.73 | 163.0388 | 119.0492 | 91.0547 |

| Trans-resveratrol | C8H8O3 | positive | 32 | 9.45 | 229.0859 | 135.0441 | 119.0499 |

| Trifolin | C21H20O10 | negative | 32 | 9.88 | 447.0937 | 284.0326 | 255.0288 |

| Vanillic acid | C8H8O4 | positive | 40 | 6.36 | 169.0496 | 111.0442 | 125.0597 |

| Verapamil (intern. standard) | C27H38N2O4 | positive | 40 | 11.04 | 455.2902 | 165.0909 | 303.2066 |

| Parameters | Delphinidin–3–O–galactoside 1 | Petunidin–3–O–glucoside | Malvidin–3–O–galaktoside | Miquelianin | Procyanidine B1 + B3 | Gallic Acid | Hyperoside + Isoquercetin | Catechin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | 0.36 | 0.61 * (0.80 **) | 0.58 * (0.80 **) | 0.77 ** (0.82 **) | 0.75 ** (0.78 *) | 0.81 ** (0.80) | 0.69 ** (0.78 *) | 0.64 * (0.75 *) |

| C1 (min) | −0.12 | −0.51 (−0.84 **) | −0.25 (−0.31) | −0.84 ** (−0.91) | −0.75 ** (−0.99 **) | −0.81 ** (−0.98) | −0.88 ** (−0.95 **) | −0.66 * (−0.99 **) |

| Dough stability (min) | −0.24 | −0.44 (−0.53) | −0.38 (−0.35) | −0.53 (−0.55) | −0.60 * (−0.63) | −0.64 * (−0.65) | −0.48 (−0.53) | −0.52 (−0.62) |

| C2 (Nm) | −0.41 | −0.20 (0.30) | −0.14 (0.50) | 0.11 (0.40) | −0.15 (0.50) | −0.10 (0.40) | 0.24 (−0.40) | −0.12 (0.50) |

| C1–C2 (Nm) | 0.41 | 0.20 (−0.30) | 0.14 (−0.50) | −0.11 (−0.40) | 0.15 (−0.50) | 0.10 (−0.40) | −0.24 (−0.40) | 0.12 (−0.50) |

| C3 (Nm) | −0.48 | −0.05 (0.78 *) | −0.20 (0.45) | 0.44 (0.83 **) | 0.01 (0.78 *) | 0.07 (0.77 *) | 0.56 * (0.78 *) | −0.02 (0.80 **) |

| C4 (Nm) | −0.54 | −0.10 (0.75 *) | −0.30 (0.32) | 0.47 (0.83 **) | 0.01 (0.83 **) | 0.05 (0.82 **) | 0.62 * (0.83 **) | −0.04 (0.85 **) |

| C3–C4 (Nm) | 0.16 | −0.28 (−0.75 *) | −0.02 (−0.29) | −0.85 ** (−0.83 **) | −0.49 (−0.85 **) | −0.54 (−0.83 **) | −0.92 ** (−0.95 **) | −0.39 (−0.87 **) |

| C5 (Nm) | 0.06 | 0.45 (0.79 *) | 0.25 (0.32) | 0.77 ** (0.85 **) | 0.53 (0.82 **) | 0.63 * (0.83 **) | 0.76 ** (0.85 **) | 0.53 (0.85 **) |

| Samples | Volume (mL) | Height (cm) | Width (cm) | Height/Width | Bread Yield (cm3/100 g WF 1) | Specific Volume (cm3/100 g bun) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat bun (WB) | 245 ± 1.7 d | 6.6 ± 0.2 d | 8.4 ± 0.2 c | 0.8 ± 0.0 b | 499.2 ± 3.4 e | 356.6 ± 2.4 d |

| WB + 5% W. pomace | 204 ± 21.1 c | 6.0 ± 0.2 cd | 8.2 ± 0.3 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 413.9 ± 41.8 b | 291.8 ± 33.3 c |

| WB + 10% W. pomace | 133 ± 25.7 b | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 0.3 bc | 0.6 ± 0.1 c | 265.9 ± 53.5 c | 189.1 ± 37.4 b |

| WB + 20% W. pomace | 95 ± 5.9 a | 3.6 ± 0.3 ab | 7.6 ± 0.1 ab | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 194.4 ± 11.5 ab | 134.9 ± 7.6 a |

| WB + 30% W. pomace | 74 ± 5.4 a | 3.1 ± 0.3 a | 7.6 ± 0.4 ab | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 155.8 ± 11.3 a | 107.1 ± 7.8 a |

| WB + 5% R. pomace | 213 ± 0.0 c | 5.7 ± 0.3 c | 8.5 ± 0.2 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 bc | 429.3 ± 15.2 de | 304.9 ± 6.9 cd |

| WB + 10% R. pomace | 130 ± 3.3 b | 4.1 ± 0.1 b | 8.0 ± 0.1 abc | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 260.9 ± 6.7 bc | 189.6 ± 4.9 b |

| WB + 20% R. pomace | 90 ± 3.3 a | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab | 7.5 ± 0.2 ab | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 185.9 ± 6.9 ab | 129.2 ± 4.8 a |

| WB + 30% R. pomace | 73 ± 0.0 a | 3.6 ± 0.1 ab | 7.3 ± 0.4 a | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 159.1 ± 8.7 a | 111.2 ± 4.6 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dvořáček, V.; Jágr, M.; Jelínek, M.; Jurkaninová, L.; Fraňková, A. Processing-Induced Changes in Phenolic Composition and Dough Properties of Grape Pomace-Enriched Wheat Buns. Foods 2025, 14, 4256. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244256

Dvořáček V, Jágr M, Jelínek M, Jurkaninová L, Fraňková A. Processing-Induced Changes in Phenolic Composition and Dough Properties of Grape Pomace-Enriched Wheat Buns. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4256. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244256

Chicago/Turabian StyleDvořáček, Václav, Michal Jágr, Michael Jelínek, Lucie Jurkaninová, and Adéla Fraňková. 2025. "Processing-Induced Changes in Phenolic Composition and Dough Properties of Grape Pomace-Enriched Wheat Buns" Foods 14, no. 24: 4256. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244256

APA StyleDvořáček, V., Jágr, M., Jelínek, M., Jurkaninová, L., & Fraňková, A. (2025). Processing-Induced Changes in Phenolic Composition and Dough Properties of Grape Pomace-Enriched Wheat Buns. Foods, 14(24), 4256. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244256