Impact of Different Grilling Temperatures on the Volatile Profile of Beef

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation Experimental Protocol and Cooking Procedure

2.2. Volatile Extraction and GC-MS Analysis

2.3. Data Processing and Identification of VOCs

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

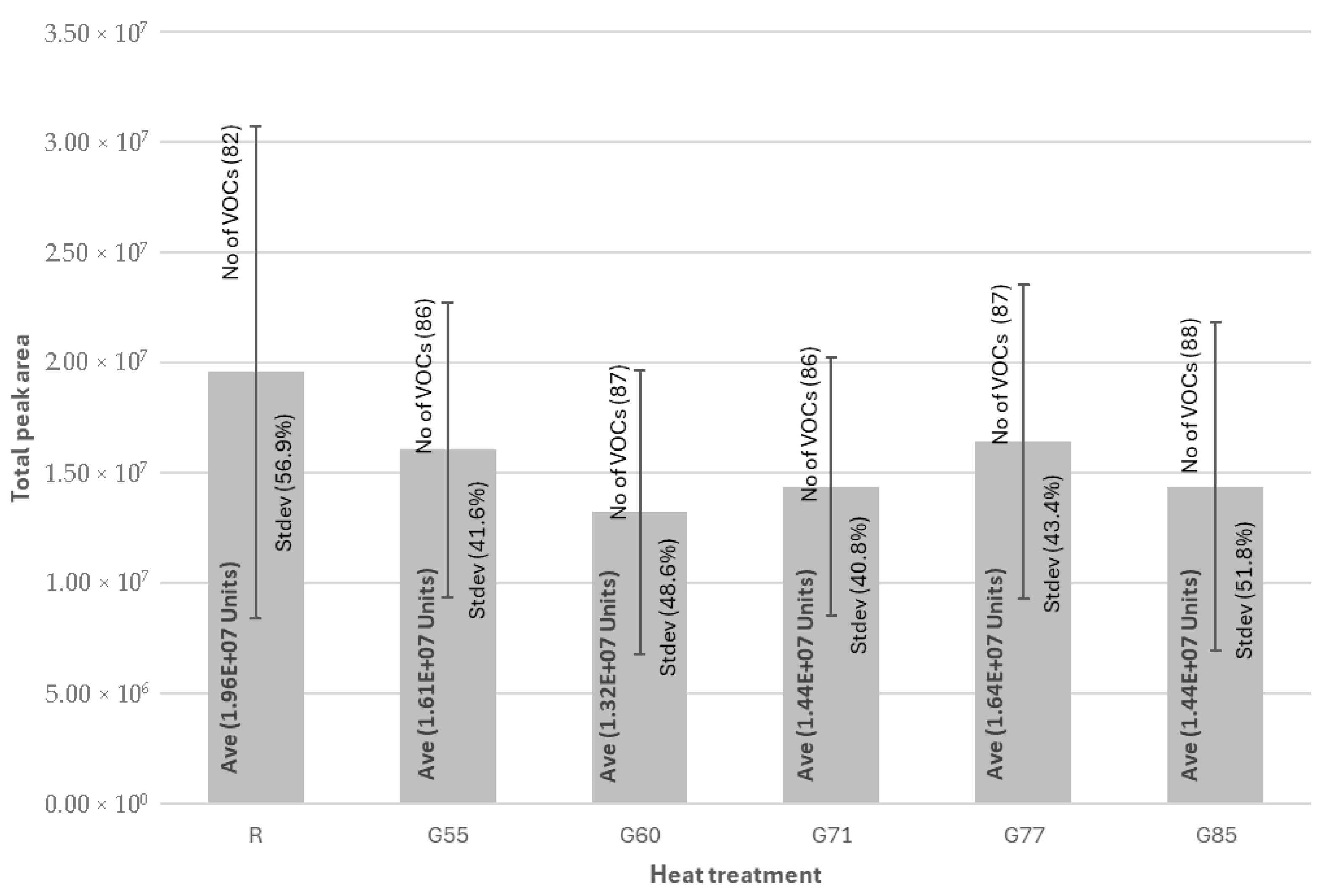

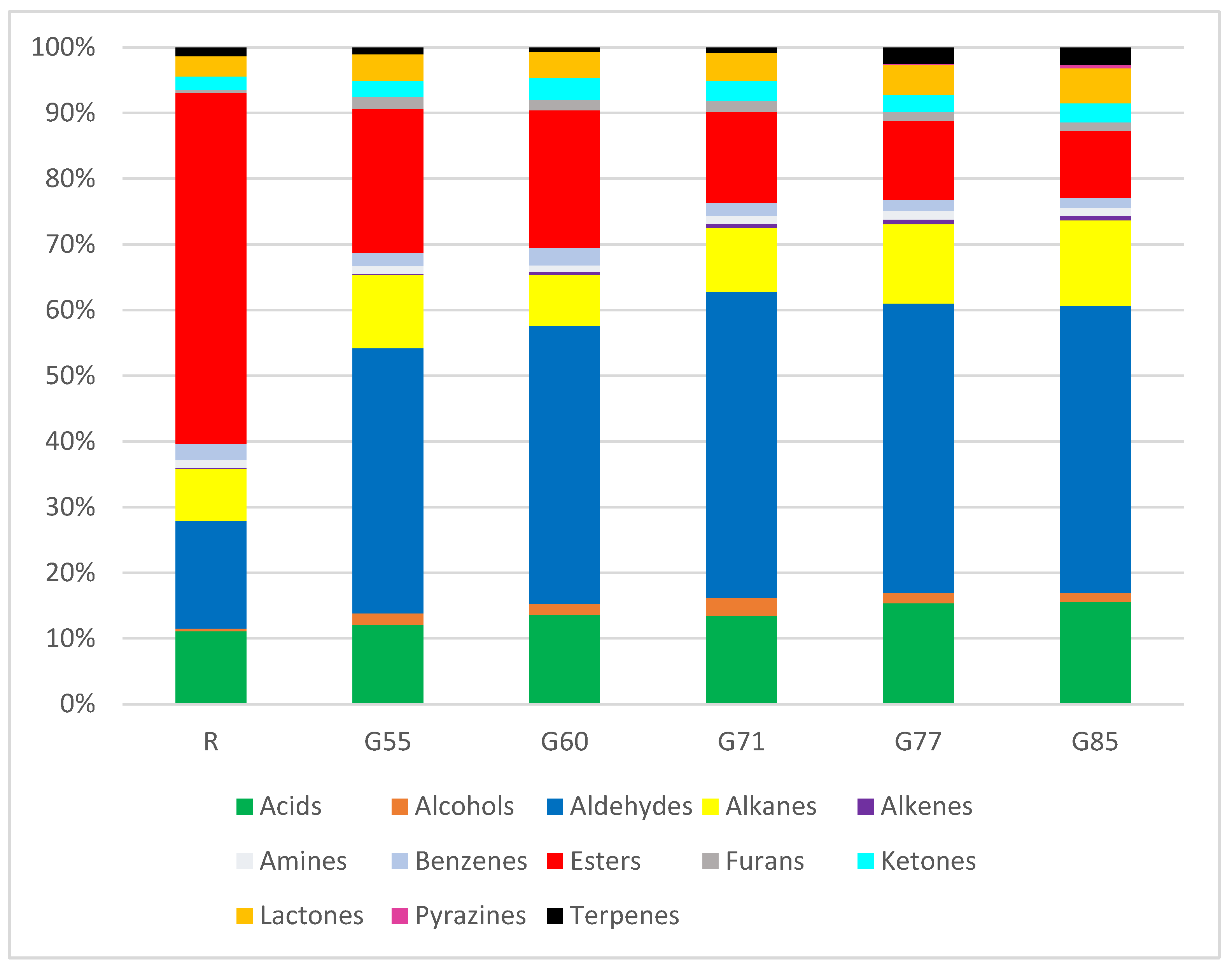

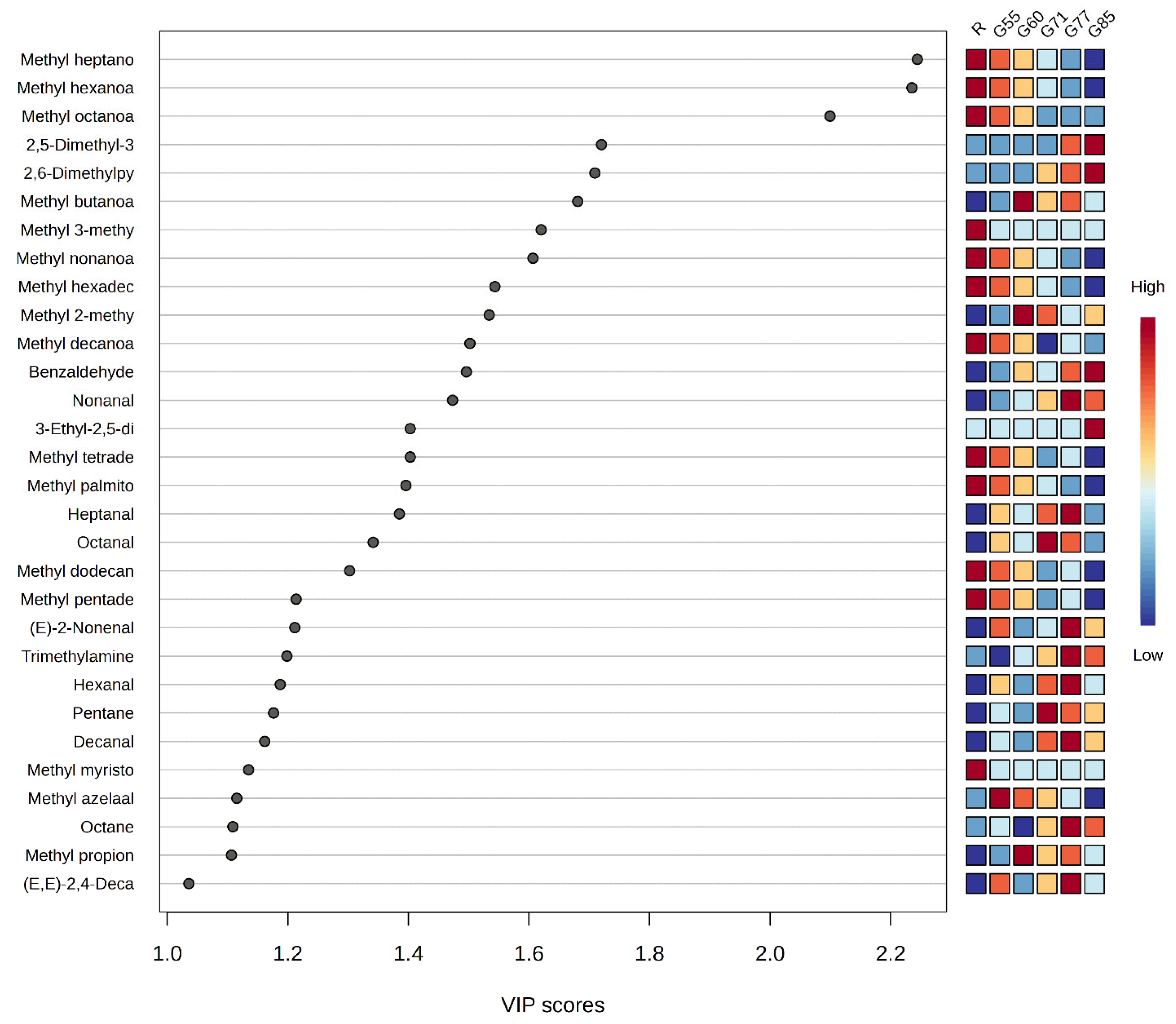

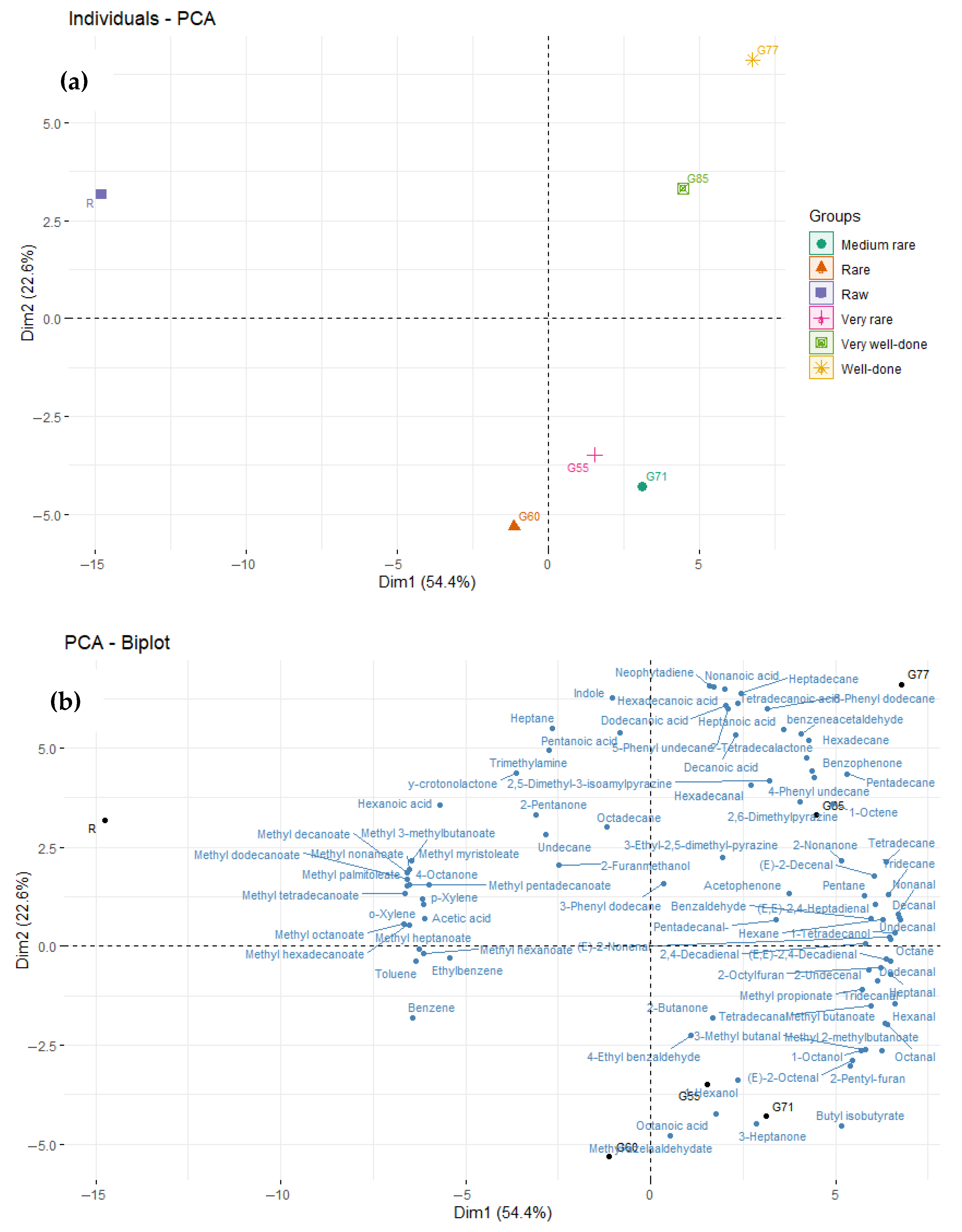

Comparison of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and Chemical Classes in Raw and Grilled Beef as Impacted by Degree of Doneness

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOC | Volatile organic compounds |

| GC–MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| DI-HiSorb | Direct immersion high-capacity sorptive extraction |

| HS-SPME | Headspace solid-phase microextraction |

References

- Kerth, C.R.; Legako, J.F.; Woerner, D.R.; Brooks, J.C.; Lancaster, J.M.; O’Quinn, T.G.; Nair, M.; Miller, R.K. A current review of U.S. beef flavor I: Measuring beef flavor. Meat Sci. 2024, 210, 109437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Quinn, T.G.; Legako, J.F.; Brooks, J.C.; Miller, M.F. Evaluation of the contribution of tenderness, juiciness, and flavor to the overall consumer beef eating experience1. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2018, 2, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, K.; Chambers Iv, E.; Miller, R.; VÁZquez-AraÚJo, L.; Bhumiratana, N.; Philip, C. Development of a lexicon for beef flavor in intact muscle. J. Sens. Stud. 2011, 26, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, F.; Cincotta, F.; Condurso, C.; Verzera, A.; Panebianco, A. Odor Emissions from Raw Meat of Freshly Slaughtered Cattle during Inspection. Foods 2021, 10, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, G.; Ames, J.M. The effect of heat on beef aroma: Comparisons of chemical composition and sensory properties. Flavour Fragr. J. 1986, 1, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram, D.S. Flavour formation in meat and meat products: A review. Food Chem. 1998, 62, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Han, Y.; Xu, L.; Jin, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, H. Analysis of volatile compounds between raw and cooked beef by HS-SPME–GC–MS. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 42, e13503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, J.S.; Warren, H.E.; Mottram, D.S.; Scollan, N.D.; Enser, M.; Richardson, R.I.; Wood, J.D. A comparison of the aroma volatiles and fatty acid compositions of grilled beef muscle from Aberdeen Angus and Holstein-Friesian steers fed diets based on silage or concentrates. Meat Sci. 2004, 68, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legako, J.F.; Brooks, J.C.; O’Quinn, T.G.; Hagan, T.D.J.; Polkinghorne, R.; Farmer, L.J.; Miller, M.F. Consumer palatability scores and volatile beef flavor compounds of five USDA quality grades and four muscles. Meat Sci. 2015, 100, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, K.; Balcaen, A.; Dirinck, P.; De Winne, A.; Claeys, E.; Demeyer, D.; De Smet, S. Meat quality, fatty acid composition and flavour analysis in Belgian retail beef. Meat Sci. 2003, 65, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinaga, K.; Tago, A.; Yoshinaga-Kiriake, A.; Gotoh, N. Characterization of lactones in Wagyu (Japanese beef) and imported beef by combining solvent extraction and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. LWT 2021, 135, 110015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, D.L.; Garmyn, A.J.; Legako, J.F.; Woemer, D.R.; Miller, M.F. Flavor Characterization of Grass- and Grain-Fed Australian Beef Longissimus Lumborum Wet-Aged 45 to 135 Days. Meat Muscle Biol. 2020, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Woerner, D.R.; de Mancilha Franco, T.; Miller, M.F.; Legako, J.F. Development of Beef Volatile Flavor Compounds in Response to Varied Oven Temperature and Degree of Doneness. Meat Muscle Biol. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bu, X.; Yang, D.; Deng, D.; Lei, Z.; Guo, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Q. Effect of Cooking Method and Doneness Degree on Volatile Compounds and Taste Substance of Pingliang Red Beef. Foods 2023, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Moloney, A.P.; Monahan, F.J.; Mannion, D.T.; Dunne, P.G.; Kilcawley, K.N. Use of a high capacity sorptive extraction technique to assess the volatile compounds in raw and grilled beef steak. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, C.A.; Garmyn, A.; Legako, J.; Miller, M.F. Cooking Method and USDA Quality Grade Affect Consumer Palatability and Flavor of Beef Strip Loin Steaks. Meat Muscle Biol. 2019, 3, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; Sepulveda, C.; Garmyn, A.; Legako, J.; Miller, M. Effects of Dry Heat Cooking Method and Quality Grade on the Composition and Objective Tenderness and Juiciness of Beef Strip Loin Steaks. Meat Muscle Biol. 2019, 3, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Luo, R.M.; Wang, S.L. Water distribution and key aroma compounds in the process of beef roasting. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 978622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 of 24 September 2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L 303, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament & Council. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2004, L 139, 55–205. [Google Scholar]

- AMSA. Research Guidelines for Cookery, Sensory Evaluation and Instrumental Tenderness Measurements of Meat, 2nd ed.; Version 1.0; AMSA: Kearney, MO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, K.; Legako, J.F. Volatile flavor compounds vary by beef product type and degree of doneness. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 4238–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilgannon, A.K.; Holman, B.W.B.; Frank, D.C.; Mawson, A.J.; Collins, D.; Hopkins, D.L. Temperature-time combination effects on aged beef volatile profiles and their relationship to sensory attributes. Meat Sci. 2020, 168, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrens, R.; Weingart, G.; Mattivi, F. metaMS: An open-source pipeline for GC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 966, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Soufan, O.; Li, C.; Caraus, I.; Li, S.; Bourque, G.; Wishart, D.S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: Towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W486–W494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, R.; Bremer, P.; Kebede, B.; Eyres, G.T. Comparison of Four Extraction Techniques for the Evaluation of Volatile Compounds in Spray-Dried New Zealand Sheep Milk. Molecules 2019, 24, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, E.G.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Kerry, J.P.; Kilcawley, K.N. Volatile organic compounds in beef and pork by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: A review. Sep. Sci. Plus 2022, 5, 482–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, E.; Emanuele, B.; Mieczysław, O.; Waszkiewicz-Robak, B. Volatile compounds formed under the surface of broiled and frozen minced cutlets: Effects of beef to pork ratio and initial pH. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1306–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Gómez, M.; Fonseca, S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Effect of different cooking methods on lipid oxidation and formation of volatile compounds in foal meat. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ren, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tian, H.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Xing, W.; Yu, Y.; et al. Investigation on the pro-aroma generation effects of fatty acids in beef via thermal oxidative models. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, J.W.; Ryu, M.; Jo, C. Effects of cooking conditions on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of dry- and wet-aged beef. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, C.; Grosch, W. Evaluation of potent odorants in roasted beef by aroma extract dilution analysis. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1992, 194, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osigbemeh, E.M.; Andrea, J.G.; Jerrad, F.L.; Dale, R.W.; Mark, F.M. Flavor Characterization of Grass- and Grain-Fed Australian Beef Longissimus Thoracis Aged 35 to 65 Days Postmortem. Meat Muscle Biol. 2020, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, K.R.; Kerth, C.R.; Miller, R.K.; Alvarado, C. Grilling temperature effects on tenderness, juiciness, flavor and volatile aroma compounds of aged ribeye, strip loin, and top sirloin steaks. Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrón, M.J.; Tejeda, J.F.; Muriel, E.; Ventanas, J.; Antequera, T. Study of the branched hydrocarbon fraction of intramuscular lipids from Iberian dry-cured ham. Meat Sci. 2005, 69, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalali, S.; Li, C.; Xu, B. Evaluation of the effect of marination in different seasoning recipes on the flavor profile of roasted beef meat via chemical and sensory analysis. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xia, D.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y. Analysis of aroma-active compounds in four Chinese dry-cured hams based on GC-O combined with AEDA and frequency detection methods. LWT 2022, 153, 112497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, Y.L.; Shindyapina, A.V.; Sheshukova, E.V.; Komarova, T.V. Metabolic methanol: Molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 603–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E. Phospholipid methylation in mammals: From biochemistry to physiological function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Liu, L.; Yuan, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wen, J.; Cui, H. A Comparison of Different Tissues Identifies the Main Precursors of Volatile Substances in Chicken Meat. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 927618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.V.; Kassandra, V.M.; Travis, G.O.Q.; Jerrad, F.L. The Impact of Enhancement, Degree of Doneness, and USDA Quality Grade on Beef Flavor Development. Meat Muscle Biol. 2019, 3, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, J.W.; Kim, M.; Jo, C. Effect of Different Aging Methods on the Formation of Aroma Volatiles in Beef Strip Loins. Foods 2021, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.D.; Hunt, I.G.; Sawyer, S.M.; Kocharunchitt, C.; Li, Z.; Stanley, R.A. Electronic tongue measurements as a predictor for sensory properties of vacuum-packed minced beef—A preliminary study. Meat Sci. 2025, 220, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, J.S.; Campo, M.M.; Enser, M.; Mottram, D.S. Effect of Lipid Composition on Meat-like Model Systems Containing Cysteine, Ribose, and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, D.; Yim, J.; Lee, K.G. Analysis of 8-oxooctanoate, 9-oxononanoate, fatty acids, oxidative stability, and iodine value during deep-frying of French fries in edible oils blended with palm oil. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 2761–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, J.S.; Mottram, D.S.; Enser, M.; Wood, J.D. Effect of the Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Composition of Beef Muscle on the Profile of Aroma Volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleicher, J.; Ebner, E.E.; Bak, K.H. Formation and Analysis of Volatile and Odor Compounds in Meat—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.-T.; Chen, Q. Lipids in Food Flavors An Overview. In Lipids in Food Flavors; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; Volume 558, pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bota, G.M.; Harrington, P.B. Direct detection of trimethylamine in meat food products using ion mobility spectrometry. Talanta 2006, 68, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.K.; Kim, B.-G.; Kang, M.-C.; Kim, T.-K.; Choi, Y.-S. Distinctive volatile compound profile of different raw meats, including beef, pork, chicken, and duck, based on flavor map. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gemert, L.J. Odour thresholds: Compilations of Odour Threshold Values in Air, Water and Other Media, 2nd Enlarged and Revised ed.; Oliemans Punter & Partners BV: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burdock, G.A. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients; CRC Press/Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, A.; Al-Dalali, S.; Wang, J.; Xie, J.; Shakoor, A.; Asimi, S.; Shah, H.; Patil, P. Aroma compounds identified in cooked meat: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yang, P.; Liu, C.; Song, H.; Pan, W.; Gong, L. Characterization of key odor-active compounds in thermal reaction beef flavoring by SGC× GC-O-MS, AEDA, DHDA, OAV and quantitative measurements. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 114, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayne, S.; Forest, K. Carboxylic acid ester hydrolysis rate constants for food and beverage aroma compounds. Flavour Fragr. J. 2016, 31, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selli, S.; Rannou, C.; Prost, C.; Robin, J.; Serot, T. Characterization of Aroma-Active Compounds in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Eliciting an Off-Odor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9496–9502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, C.R.; Hodgen, J.M. A fresh look at meat flavor. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerny, M.; Christlbauer, M.; Christlbauer, M.; Fischer, A.; Granvogl, M.; Hammer, M.; Hartl, C.; Hernandez, N.; Schieberle, P. Re-investigation on odour thresholds of key food aroma compounds and development of an aroma language based on odour qualities of defined aqueous odorant solutions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 228, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Qin, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Huang, D.; Xiang, D.; Liu, X. Effect of the chemical composition and structural properties of beef tallow from different adipose tissues on bread quality. LWT 2024, 192, 115736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.S.; Bassette, R.; Ward, G. Trimethylamine responsible for fishy flavour in milk from cos on wheat pasture. J. Dairy Sci. 1974, 57, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Class | Individual VOCs | CAS Number | LRI | Ref LRI | Volatiles Expressed as Percentage of Total (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | G55 | G60 | G71 | G77 | G85 | p Value | |||||

| Aldehydes | 3-Methyl butanal | 590-86-3 | 653 | 651 | 2.21 | 5.59 | 5.56 | 5.29 | 4.55 | 5.33 | ns |

| Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 802 | 801 | 1.12 | 3.78 | 4.16 | 4.49 | 4.06 | 3.86 | <0.01 | |

| Heptanal | 111-71-7 | 904 | 901 | 1.21 | 4.69 | 5.25 | 6.17 | 5.94 | 4.75 | <0.01 | |

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 970 | 960 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.58 | <0.01 | |

| Octanal | 124-13-0 | 1005 | 1004 | 0.57 | 3.01 | 3.36 | 3.97 | 3.29 | 2.93 | <0.01 | |

| (E,E)-2,4-Heptadienal | 4313-03-5 | 1015 | 1014 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.17 | <0.01 | |

| (E)-2-Octenal | 2548-87-0 | 1061 | 1061 | 0.10 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.50 | <0.01 | |

| Nonanal | 124-19-6 | 1108 | 1106 | 5.95 | 9.95 | 12.33 | 12.62 | 12.07 | 12.72 | <0.01 | |

| (E)-2-Nonenal | 18829-56-6 | 1164 | 1160 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.64 | <0.01 | |

| 4-Ethyl benzaldehyde | 4748-78-1 | 1174 | 1164 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.39 | ns | |

| Decanal | 112-31-2 | 1209 | 1205 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.70 | <0.01 | |

| (E)-2-Decenal | 3913-81-3 | 1267 | 1266 | 0.60 | 1.59 | 1.97 | 1.44 | 2.15 | 2.05 | ns | |

| (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal | 25152-84-5 | 1302 | 1299 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.26 | <0.01 | |

| Undecanal | 112-44-7 | 1311 | 1309 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.27 | ns | |

| 2,4-Decadienal | 2363-88-4 | 1326 | 1317 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.67 | <0.01 | |

| 2-Undecenal | 2463-77-6 | 1370 | 1369 | 0.31 | 1.89 | 1.11 | 1.61 | 1.60 | 1.51 | <0.01 | |

| Dodecanal | 112-54-9 | 1413 | 1401 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.33 | <0.01 | |

| Tridecanal | 10486-19-8 | 1516 | 1505 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.01 | |

| Tetradecanal | 124-25-4 | 1618 | 1615 | 0.24 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.02 | |

| Pentadecanal | 2765-11-9 | 1716 | 1707 | 0.88 | 1.45 | 1.07 | 1.51 | 1.27 | 1.37 | ns | |

| Hexadecanal | 629-80-1 | 1818 | 1819 | 1.69 | 1.98 | 1.79 | 2.58 | 2.33 | 3.46 | ns | |

| benzeneacetaldehyde | 122-78-1 | 1052 | 1051 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.12 | ns | |

| Esters | Methyl propionate | 554-12-1 | 626 | 620 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.22 | <0.01 |

| Methyl butanoate | 623-42-7 | 720 | 719 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.71 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl 2-methylbutanoate | 868-57-5 | 775 | 774 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 0.97 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl 3-methylbutanoate | 556-24-1 | 776 | 774 | 6.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl hexanoate | 106-70-7 | 923 | 922 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.12 | <0.01 | |

| Butyl isobutyrate | 97-87-0 | 951 | 951 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.26 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | 1023 | 1022 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.05 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | 1124 | 1126 | 2.48 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1223 | 1225 | 3.59 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.19 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl decanoate | 110-42-9 | 1324 | 1322 | 4.25 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.37 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl azelaaldehydate | 1931-63-1 | 1434 | 1439 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl dodecanoate | 111-82-0 | 1524 | 1522 | 1.25 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl myristoleate | 56219-06-8 | 1714 | 1715 | 1.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl tetradecanoate | 124-10-7 | 1726 | 1724 | 10.01 | 3.21 | 2.72 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 0.79 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl pentadecanoate | 7132-64-1 | 1826 | 1820 | 1.93 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.29 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl palmitoleate | 1120-25-8 | 1907 | 1899 | 3.82 | 1.44 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.79 | <0.01 | |

| Methyl hexadecanoate | 112-39-0 | 1927 | 1927 | 16.48 | 10.75 | 10.52 | 7.87 | 6.70 | 5.27 | <0.01 | |

| Alkanes | Octane | 111-65-9 | 802 | 801 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 1.45 | 2.26 | 2.30 | 1.62 | <0.01 |

| Pentane | 109-66-0 | 502 | 500 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.38 | <0.01 | |

| Hexane | 110-54-3 | 602 | 600 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.67 | ns | |

| Heptane | 142-82-5 | 701 | 700 | 3.32 | 2.73 | 2.06 | 2.99 | 3.41 | 3.38 | <0.01 | |

| Undecane | 1120-21-4 | 1101 | 1100 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.24 | ns | |

| Tridecane | 629-50-5 | 1302 | 1300 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.27 | ns | |

| Tetradecane | 629-59-4 | 1402 | 1400 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.39 | ns | |

| Pentadecane | 629-62-9 | 1502 | 1500 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.64 | ns | |

| Hexadecane | 544-76-3 | 1601 | 1600 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.47 | ns | |

| 5-Phenyl undecane | 4537-15-9 | 1640 | 1632 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ns | |

| 4-Phenyl undecane | 4536-86-1 | 1652 | 1643 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.11 | ns | |

| Heptadecane | 629-78-7 | 1701 | 1700 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 1.05 | 1.09 | ns | |

| 6-Phenyl dodecane | 2719-62-2 | 1735 | 1726 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ns | |

| 3-Phenyl dodecane | 2400-00-2 | 1779 | 1766 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.13 | ns | |

| Octadecane | 593-45-3 | 1799 | 1810 | 2.22 | 3.31 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 1.77 | 3.45 | ns | |

| Acids | Acetic acid | 64-19-7 | 577 | 559 | 1.44 | 1.51 | 1.65 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.38 | ns |

| Pentanoic acid | 109-52-4 | 881 | 868 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.41 | ns | |

| Hexanoic acid | 142-62-1 | 968 | 983 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.61 | ns | |

| Heptanoic acid | 111-14-8 | 1066 | 1080 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.91 | ns | |

| Octanoic acid | 124-07-2 | 1164 | 1160 | 0.71 | 1.45 | 1.27 | 1.23 | 0.95 | 0.99 | ns | |

| Nonanoic acid | 112-05-0 | 1264 | 1276 | 1.85 | 1.97 | 2.26 | 2.33 | 2.67 | 2.74 | ns | |

| Decanoic acid | 334-48-5 | 1359 | 1358 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 1.24 | 1.44 | 1.33 | ns | |

| Dodecanoic acid | 143-07-7 | 1557 | 1555 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.73 | ns | |

| Tetradecanoic acid | 544-63-8 | 1757 | 1760 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 1.21 | 1.05 | ns | |

| Hexadecanoic acid | 57-10-3 | 1967 | 1967 | 3.42 | 3.34 | 3.73 | 4.09 | 5.07 | 5.37 | ns | |

| Benzenes | Benzene | 71-43-2 | 662 | 669 | 1.03 | 0.73 | 1.15 | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.42 | ns |

| Toluene | 108-88-3 | 770 | 763 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.32 | ns | |

| Ethylbenzene | 100-41-4 | 866 | 867 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | ns | |

| p-Xylene | 106-42-3 | 868 | 863 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | ns | |

| o-Xylene | 95-47-6 | 899 | 908 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | ns | |

| Benzophenone | 119-61-9 | 1656 | 1653 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.20 | ns | |

| Indole | 120-72-9 | 1306 | 1296 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ns | |

| Ketones | 2-Butanone | 78-93-3 | 599 | 597 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 0.68 | 0.79 | ns |

| 2-Pentanone | 107-87-9 | 684 | 687 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.24 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 | ns | |

| 3-Heptanone | 106-35-4 | 886 | 887 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.20 | ns | |

| 4-Octanone | 589-63-9 | 974 | 977 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.40 | ns | |

| Acetophenone | 98-86-2 | 1074 | 1079 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | ns | |

| 2-Nonanone | 821-55-6 | 1094 | 1094 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.29 | ns | |

| Alcohols | 1-Hexanol | 111-27-3 | 867 | 868 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 1.28 | 0.25 | 0.16 | ns |

| 1-Octanol | 111-87-5 | 1071 | 1071 | 0.26 | 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.22 | 1.09 | 0.92 | <0.01 | |

| 1-Tetradecanol | 112-72-1 | 1681 | 1671 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.28 | ns | |

| Furans | 2-Furanmethanol | 98-00-0 | 852 | 850 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.07 | ns |

| 2-Pentylfuran | 3777-69-3 | 993 | 991 | 0.28 | 1.70 | 1.33 | 1.51 | 1.19 | 1.19 | <0.01 | |

| 2-Octylfuran | 4179-38-8 | 1296 | 1286 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | <0.01 | |

| Pyrazines | 2,6-Dimethylpyrazine | 108-50-9 | 918 | 912 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | <0.01 |

| 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethylpyrazine | 13360-65-1 | 1080 | 1072 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | <0.01 | |

| 2,5-Dimethyl-3-isoamylpyrazine | 111150-30-2 | 1319 | 1322 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.30 | <0.01 | |

| Lactones | y-crotonolactone | 497-23-4 | 912 | 916 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.34 | ns |

| δ-Tetradecalactone | 2721-22-4 | 1939 | 1938 | 2.74 | 3.67 | 3.71 | 3.98 | 4.16 | 4.95 | ns | |

| Alkenes | 1-Octene | 111-66-0 | 792 | 791 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.68 | ns |

| Amines | Trimethylamine | 75-50-3 | 480 | 479 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 1.30 | 1.19 | 0.02 |

| Terpenes | Neophytadiene | 504-96-1 | 1841 | 1837 | 1.32 | 1.02 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 2.52 | 2.70 | ns |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |||||

| Individual VOCs | CAS Number | VIP Score | Odour Descriptor | Odour Ref | Odour Threshold * (ppm) | Odour Threshold Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | 2.244 | Faint, waxy, nearly tasteless | [50] | 0.004 | [51] |

| Methyl hexanoate | 106-70-7 | 2.235 | Ethereal fruity, pineapple-like | [50] | 0.039–0.43 | [51] |

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | 2.099 | Strong, winey, fruity, orange-like | [52] | 0.27–0.87 | [51] |

| 2,5-Dimethyl-3-isoamylpyrazine | 111150-30-2 | 1.720 | Sweet, fragrant | [53] | na | |

| 2,6-Dimethylpyrazine | 108-50-9 | 1.709 | Coffee, nutty | [54] | 1.5 | [51] |

| Methyl butanoate | 623-42-7 | 1.681 | Ethereal fruity-apple odour, apple-like taste | [50] | 0.043 | [51] |

| Methyl 3-methylbutanoate | 556-24-1 | 1.620 | Strong, fruity, ethereal, pineapple-apple | [50] | 0.0044–0.044 | [51] |

| Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1.607 | Coconut | [55] | 0.0005 | [51] |

| Methyl hexadecanoate | 112-39-0 | 1.544 | Green, fruity, fatty | [56] | >2 | [51] |

| Methyl 2-methylbutanoate | 868-57-5 | 1.534 | Fruity, sweet, apple, berry, ripe tropical notes | [50] | 0.0001–0.00014 | [51] |

| Methyl decanoate | 110-42-9 | 1.502 | wine | [55] | 0.0043–0.0088 | [51] |

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 1.496 | Volatile almond oil, bitter almond, burning aromatic taste | [57] | 0.35 | [51] |

| Nonanal | 124-19-6 | 1.473 | Citrus-like, soapy | [58] | 0.001 | [51] |

| 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethyl-pyrazine | 13360-65-1 | 1.403 | Earthy, musty | [53] | 0.0004 | [51] |

| Methyl tetradecanoate | 124-10-7 | 1.403 | Orris | [59] | na | |

| Methyl palmitoleate | 1120-25-8 | 1.396 | na | na | ||

| Heptanal | 111-71-7 | 1.385 | Oily, fatty, rancid, unpleasant, penetrating fruity odour in liquid | [57] | 0.003 | [51] |

| Octanal | 124-13-0 | 1.342 | Citrus-like, green | [58] | 0.007 | [51] |

| Methyl dodecanoate | 111-82-0 | 1.303 | Coconut, fatty | [59] | na | |

| Methyl pentadecanoate | 7132-64-1 | 1.214 | na | na | ||

| (E)-2-Nonenal | 18829-56-6 | 1.212 | Fatty, green | [58] | 0.00008 | [51] |

| Trimethylamine | 75-50-3 | 1.199 | Fishy | [60] | 0.0005 | [51] |

| Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 1.187 | Green, grassy | [58] | 0.005 | [51] |

| Pentane | 109-66-0 | 1.176 | Very slight warmed-over flavour, oxidized | [57] | na | [51] |

| Decanal | 112-31-2 | 1.162 | Orange, citrus | [52] | 0.003 | [51] |

| Methyl myristoleate | 56219-06-8 | 1.135 | Geranium, metallic, pungent | [59] | na | |

| Methyl azelaaldehydate | 1931-63-1 | 1.115 | na | na | ||

| Octane | 111-65-9 | 1.109 | Hydrocarbon odour (weak) | [50] | 10 | [51] |

| Methyl propionate | 554-12-1 | 1.107 | Reminiscent of rum | [52] | 0.1 | [51] |

| (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal | 25152-84-5 | 1.036 | Fatty, deep fried | [58] | 0.00007 | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morsli, F.; Moloney, A.P.; Monahan, F.J.; Dunne, P.G.; Mannion, D.T.; Skibinska, I.; Kilcawley, K.N. Impact of Different Grilling Temperatures on the Volatile Profile of Beef. Foods 2025, 14, 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244239

Morsli F, Moloney AP, Monahan FJ, Dunne PG, Mannion DT, Skibinska I, Kilcawley KN. Impact of Different Grilling Temperatures on the Volatile Profile of Beef. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244239

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorsli, Fathi, Aidan P. Moloney, Frank J. Monahan, Peter G. Dunne, David T. Mannion, Iwona Skibinska, and Kieran N. Kilcawley. 2025. "Impact of Different Grilling Temperatures on the Volatile Profile of Beef" Foods 14, no. 24: 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244239

APA StyleMorsli, F., Moloney, A. P., Monahan, F. J., Dunne, P. G., Mannion, D. T., Skibinska, I., & Kilcawley, K. N. (2025). Impact of Different Grilling Temperatures on the Volatile Profile of Beef. Foods, 14(24), 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244239