Novel Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Peptide Derived from Yak Bone Collagen Alleviates the Skin Inflammation of Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Modulating Skin Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Peptide-Containing Hydrogels

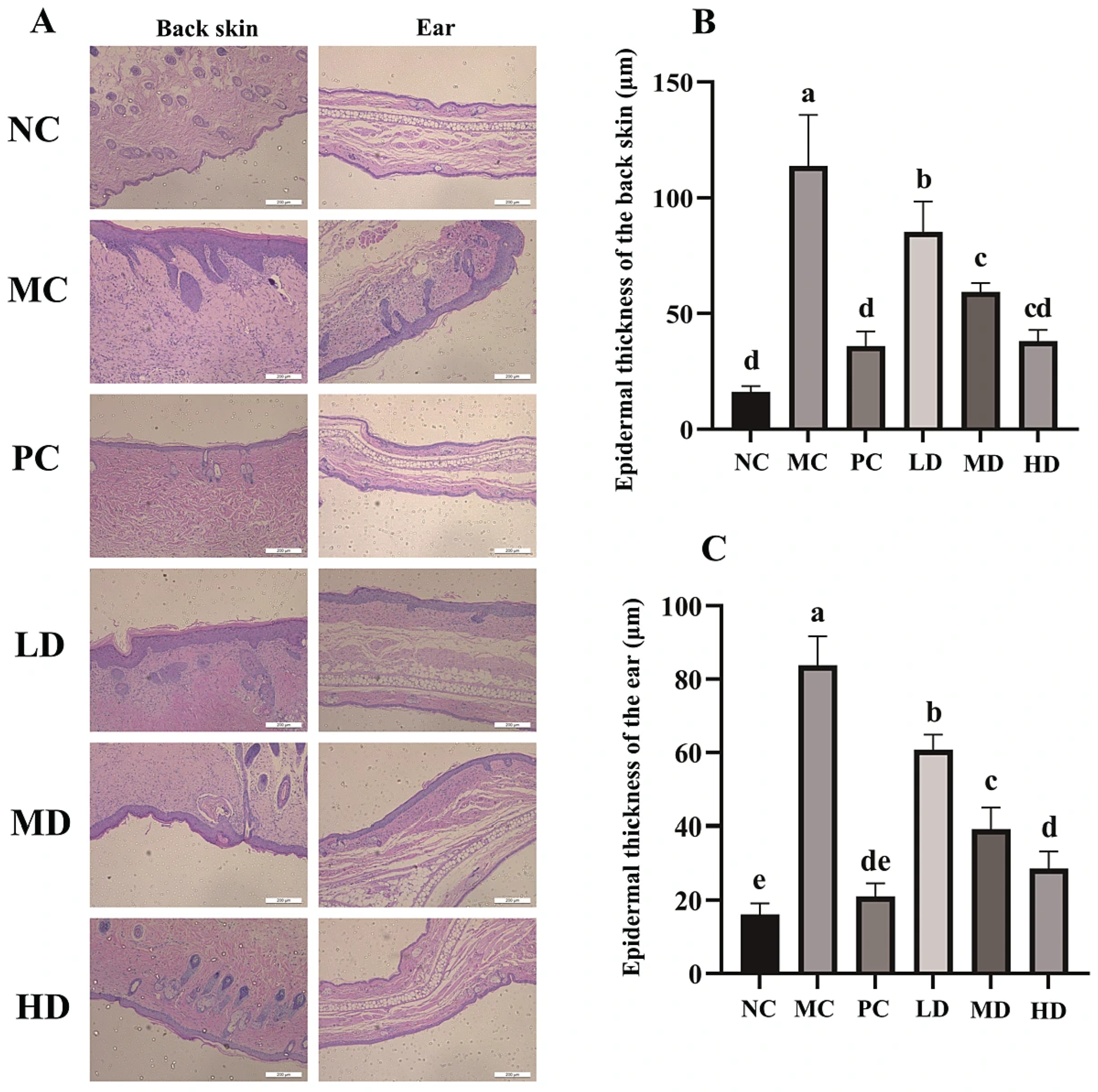

2.3. Animals and Experiment Design

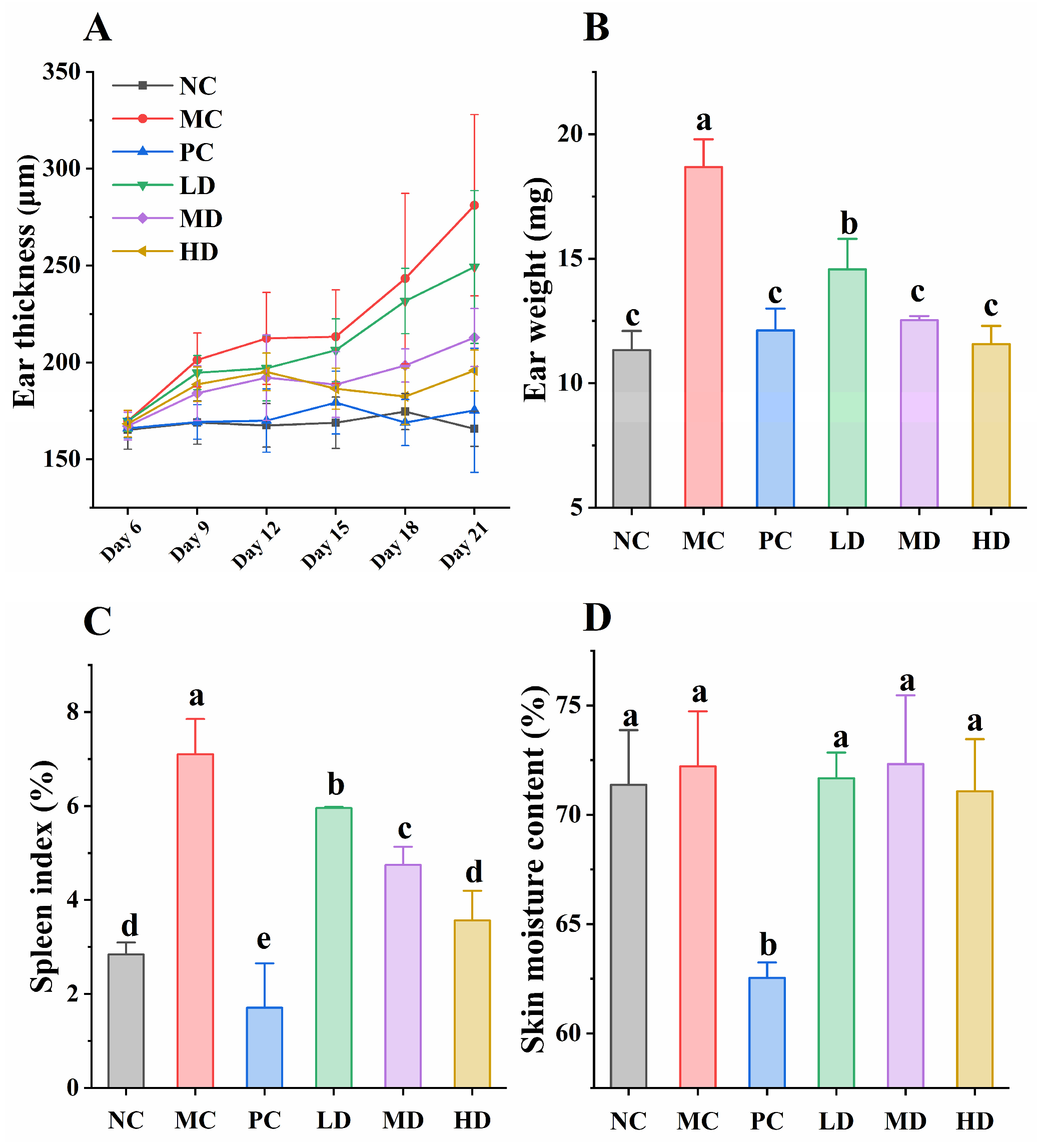

2.4. Skin Moisture Content

2.5. Ear Thickness and Weight

2.6. Histopathological Analysis of Mouse Skin and Ear

2.7. Determination of Spleen Index

2.8. Quantification of Serum Inflammatory Factors

2.9. Western Blotting

2.10. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Anti-Inflammatory Peptides on the Appearance of Mouse Skin

3.2. Immune Response and Skin Moisture Content in Mice

3.3. Histopathology of the Back Skin and the Ear

3.4. Determination of Serum Inflammatory Factors in Mice

3.5. Effects of GR14 on the Phosphorylation of Key Proteins in the NF-κB Signaling Pathway

3.6. Effects of GR14 on the Modulation of Skin Microbiota

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, D.X.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, G.S.; Kan, Z.P.; Wang, X.X.; Wang, H.S.; Huang, J.B.; Wang, T.T.; Qian, F.; Ho, C.T.; et al. Protective Effect and Mechanism of Theanine on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation and Acute Liver Injury in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7674–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB, Inflammation, and Metabolic Disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Nutma, E.; van der Valk, P.; Amor, S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2018, 154, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrè, V.; De Luca, R.; Mrmic, S.; Marotta, S.; Nardone, S.; Incerpi, S.; Giannelli, G.; Negro, R.; Trivedi, P.; Anastasiadou, E. Gastrointestinal inflammation and cancer: Viral and bacterial interplay. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2519703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Chan, F.K.L. Current knowledge on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-bowel damage: A comprehensive review. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Hawkins, K.; Shokrian, N.; Del Duca, E.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Monoclonal antibodies for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A look at phase III and beyond. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2024, 24, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.X.; Zhou, J.; Cui, H.Y.; Xu, W.D.; He, Y.Q.; Ma, H.L.; Gao, R.C. Effect of oral administration of collagen hydrolysates from Nile tilapia on the chronologically aged skin. J. Funct. Food. 2018, 44, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.L.; Zheng, F.P.; Gao, R.C. Food-derived collagen peptides: Safety, metabolism, and anti-skin-aging effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 51, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Chu, Q.; Yang, B.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Q.; Gao, R. Purification and identification of anti-inflammatory peptides from sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii) cartilage. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, M.; Li, D.; Wu, H. Collagen Hydrolysate Corrects Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease via Anti-Inflammatory Renoprotection and HIF-2α-Dependent Erythropoietin and Hepcidin Regulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 11726–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Fu, L.; Cao, S.; Yin, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, W. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Bovine Bone-Gelatin-Derived Peptides in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Macrophages Cells and Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced C57BL/6 Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Zhu, L.Y.; Guo, Z.T.; Liu, C.Y.; Hu, B.; Li, M.Y.; Gu, Z.H.; Xin, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Guan, Y.M.; et al. Yak bone collagen-derived anti-inflammatory bioactive peptides alleviate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory by inhibiting the NF-KB signaling pathway and nitric oxide production. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, Z.W.; Li, W.H.; Yao, L.Y.; Xiao, J.X. Biocompatible and bioactive yak bone collagen hydrolysates with controllable molecular weight for effective prevention of osteoporosis. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Hu, B.; Gu, Z.; Xin, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dong, D.; Zhang, L. Yak bone collagen-derived tetradecapeptide with excellent stability improves inflammation in HaCaT cells by regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Q.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, L. Polygonum perfoliatum L. ethanol extract ameliorates 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.X.; Bai, F.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J.L.; Gao, R.C. The anti-skin-aging effect of oral administration of gelatin from the swim bladder of Amur sturgeon. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3890–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.T.; Hu, B.; Wang, H.X.; Kong, L.Q.; Han, H.L.; Li, K.J.; Sun, S.; Lei, Z.F.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, Z.Y. Supplementation with nanobubble water alleviates obesity-associated markers through modulation of gut microbiota in high-fat diet fed mice. J. Funct. Food. 2020, 67, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, X.J.; Zhou, C.S.; Yagoub, A.A.; Ma, H.L. Effects of collagen and casein with phenolic compounds interactions on protein in vitro digestion and antioxidation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 124, 109192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.T.; Yi, D.L.; Hu, B.; Zhu, L.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Shi, Y.; Gu, Z.H.; Xin, Y.; et al. Supplementation with Yak (Bos grunniens) Bone Collagen Hydrolysate Altered the Structure of Gut Microbiota and Elevated Short-chain Fatty Acid Production in Mice. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.F.; Han, J.H.; Rather, I.A. Mouse model of DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Li, S.J.; Liu, J.P.; Kong, D.N.; Han, X.W.; Lei, P.; Xu, M.; Guan, H.Q.; Hou, D.D. Ameliorative effects of sea buckthorn oil on DNCB induced atopic dermatitis model mice via regulation the balance of Th1/Th2. BMC Complement. Med. 2020, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ding, X.Y.; Li, X.H.; Gong, M.J.; An, J.Q.; Huang, S.L. Correlation between elevated inflammatory cytokines of spleen and spleen index in acute spinal cord injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 2020, 344, 577264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Sriranganathan, N. Differential-Effects of Dexamethasone on the Thymus and Spleen—Alterations in Programmed Cell-Death, Lymphocyte Subsets and Activation of T-Cells. Immunopharmacology 1994, 28, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, N.; Sakai, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamada, K.; Nagano, M.; Yuki, T.; Sumida, Y.; Uchiwa, H. Relationship between NMF (lactate and potassium) content and the physical properties of the stratum corneum in healthy subjects. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 122, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, C.; Averbeck, M.; Diedenhofen, N.; Willenberg, A.; Anderegg, U.; Sleeman, J.P.; Simon, J.C. Dermal Hyaluronan Is Rapidly Reduced by Topical Treatment with Glucocorticoids. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuoqiong Qiu, Z.Z. Xiaochun Liu, Baichao Chen, Huibin Yin, Chaoying Gu, Xiaokai Fang, Ronghui Zhu, Tianze Yu, Wenli Mi, Hong Zhou, Yufeng Zhou, Xu Yao, Wei Li, A dysregulated sebum-microbial metabolite-IL-33 axis initiates skin inflammation in atopic dermatitis. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20212397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duque, G.A.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, B.S.; Chai, J.W.; Deng, Z.H.; Ye, T.F.; Chen, W.B.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, X.Q. Functional Characterization of a Novel Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Peptide in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 10709–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-Y.; Li, C.-C.; Lo, H.-Y.; Chen, F.-Y.; Hsiang, C.-Y. Corn Silk Extract and Its Bioactive Peptide Ameliorated Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation in Mice via the Nuclear Factor-κB Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Structural-features of food-derived bioactive peptides with anti-inflammatory activity: A brief review. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Wang, H.C.; Hsu, K.C.; Hwang, J.S. Anti-inflammatory peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of tuna cooking juice. Food Agric. Immunol. 2015, 26, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Rodríguez, A.; de Mejía, E.G.; Dia, V.P.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Milán-Carrillo, J. Extrusion improved the anti-inflammatory effect of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) hydrolysates in LPS-induced human THP-1 macrophage-like and mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages by preventing activation of NF-κB signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.F.; Chalamaiah, M.; Ren, X.F.; Ma, H.L.; Wu, J.P. Identification of New Anti-inflammatory Peptides from Zein Hydrolysate after Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion and Transport in Caco-2 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, Q.G.; Zhou, X.H.; Song, S.; Zhu, B.W. Stress resistance and lifespan extension of enhanced by peptides from mussel protein hydrolyzate. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3313–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, A.; Althobaiti, F.; Zhao, L.; Usman, M.; Chen, X.M.; Alharthi, F.; Soliman, M.M.; Shah, A.A.; Murtaza, M.A.; Nadeem, M.; et al. Anti-inflammatory potential of stevia residue extract against uric acid-associated renal injury in mice. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Shu, W.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Q.; Jin, W.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Yuan, L. Peptide fraction from sturgeon muscle by pepsin hydrolysis exerts anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages via MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, M.; Gupta, G.; Afzal, O.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Alzarea, S.I.; Kazmi, I.; Almalki, W.H.; Gulati, M.; Kaur, I.P.; Singh, S.K.; et al. Janus kinase/signal transducers and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) and its role in Lung inflammatory disease. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2023, 371, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Shen, Y.; Shu, W.; Jin, W.; Bai, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; El-Seedi, H.; Sun, Q.; Yuan, L. Sturgeon hydrolysates alleviate DSS-induced colon colitis in mice by modulating NF-κB, MAPK, and microbiota composition. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6987–6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Chalamaiah, M.; Liao, W.; Ren, X.; Ma, H.; Wu, J. Zein hydrolysate and its peptides exert anti-inflammatory activity on endothelial cells by preventing TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation. J. Funct. Food. 2020, 64, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, M.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, D.; Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. The Protective Effects of Corn Oligopeptides on Acute Alcoholic Liver Disease by Inhibiting the Activation of Kupffer Cells NF-κB/AMPK Signal Pathway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Wei, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Immunomodulation of RAW264.7 cells by CP80-1, a polysaccharide of Cordyceps cicadae, via Dectin-1/Syk/NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Agric. Immunol. 2023, 34, 2231172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qu, L.; Mijakovic, I.; Wei, Y. Advances in the human skin microbiota and its roles in cutaneous diseases. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlet, A.; Andre-Frei, V.; Del Bene, N.; Cameron, H.J.; Samuga, A.; Rawat, V.; Ternes, P.; Leoty-Okombi, S. Facial Skin Microbiome Composition and Functional Shift with Aging. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoetendal, E.G.; Akkermans, A.D.L.; Akkermans-van Vliet, W.M.; de Visser, J.A.G.M.; de Vos, W.M. The host genotype affects the bacterial community in the human gastrointestinal tract. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2001, 13, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.; Blaser, M.J. The human microbiome: At the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Gao, Z.; Tseng, C.-h.; Strober, B.E.; Pei, Z.; Blaser, M.J. Substantial Alterations of the Cutaneous Bacterial Biota in Psoriatic Lesions. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2719. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, K.A.; Brown, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus epidermidis—Skin friend or foe? PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severn, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus epidermidis and its dual lifestyle in skin health and infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhaiyan, M.; Wirth, J.S.; Saravanan, V.S. Phylogenomic analyses of the family suggest the reclassification of five species within the genus as heterotypic synonyms, the promotion of five subspecies to novel species, the taxonomic reassignment of five species to gen. nov. and the formal assignment of to the family. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5926–5936. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Ace | Chao | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 301.64 ± 66.01 | 295.38 ± 62.83 | 3.44 ± 0.24 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| MC | 1022.96 ± 561.72 | 1009.96 ± 554.68 | 7.72 ± 0.18 * | 0.97 ± 0.01 * |

| PC | 126.59 ± 50.81 | 125.52 ± 50.59 | 2.70 ± 0.16 * | 0.75 ± 0.02 * |

| LD | 838.78 ± 351.40 | 832.82 ± 346.17 | 5.51 ± 0.30 * | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| MD | 470.37 ± 61.22 | 468.00 ± 60.14 | 3.94 ± 0.21 | 0.83 ± 0.02 |

| HD | 200.84 ± 45.12 | 199.27 ± 44.77 | 2.79 ± 0.18 | 0.75 ± 0.01 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Z.; Shi, T.; Xu, P.; Wang, Z.; Hu, B.; Xin, Y.; Guo, Z.; Gu, Z.; Dong, D.; Zhang, L. Novel Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Peptide Derived from Yak Bone Collagen Alleviates the Skin Inflammation of Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Modulating Skin Microbiota. Foods 2025, 14, 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244238

Guo Z, Shi T, Xu P, Wang Z, Hu B, Xin Y, Guo Z, Gu Z, Dong D, Zhang L. Novel Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Peptide Derived from Yak Bone Collagen Alleviates the Skin Inflammation of Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Modulating Skin Microbiota. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244238

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Zitao, Tao Shi, Pengfei Xu, Zijun Wang, Bo Hu, Yu Xin, Zhongpeng Guo, Zhenghua Gu, Dake Dong, and Liang Zhang. 2025. "Novel Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Peptide Derived from Yak Bone Collagen Alleviates the Skin Inflammation of Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Modulating Skin Microbiota" Foods 14, no. 24: 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244238

APA StyleGuo, Z., Shi, T., Xu, P., Wang, Z., Hu, B., Xin, Y., Guo, Z., Gu, Z., Dong, D., & Zhang, L. (2025). Novel Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Peptide Derived from Yak Bone Collagen Alleviates the Skin Inflammation of Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Modulating Skin Microbiota. Foods, 14(24), 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244238