1. Introduction

Today, in many parts of the world, food is abundant, and eating has increasingly become a source to pleasure, comfort, and satisfaction of desires [

1]. As a result, eating behaviour is increasingly guided by hedonic aspects (e.g., pleasure, wanting, and liking) beyond homeostasis (i.e., obtaining energy for survival and maintaining bodily functions) [

2,

3]. Experiencing pleasure from eating, whether derived from social company, the physical environment, or the food itself, is not inherently problematic [

2,

4]. However, eating behaviour can be of concern when it is excessively driven by pleasure-seeking behaviour. This includes instances where individuals experience strong cravings for specific foods, that is, a strong desire, urge, or wanting to eat [

5]. Food cravings are widely recognised as a challenge for individuals attempting to modify their eating patterns [

6,

7] and have been shown to prospectively predict increased energy intake and subsequent weight gain over time [

8]. In contrast, previous research shows that more internally guided eating patterns, including intuitive eating, are associated with beneficial health outcomes such as lower BMI, reduced disordered eating and improved psychological well-being [

9,

10,

11,

12]. At the same time, everyday eating often occurs under conditions of distraction and multitasking (i.e., watching television, driving or working), which can impair satiety perception and promote food intake [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In contrast, studies indicate that more attentive forms of eating, including focused engagement with sensory properties of food, are linked to healthier dietary patterns, including reduced snack consumption [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Alongside these behavioural challenges, eating patterns have shifted considerably. Snacking now accounts for nearly one-third of daily energy intake, and a significant proportion of these snacks are energy-dense and low in essential nutrients (e.g., candy-like snacks) [

22]. Their frequent consumption has been linked to an increased risk of overweight and obesity due to their contribution to a sustained positive energy balance [

23,

24].

Various interventions and strategies (e.g., public health campaigns, official dietary guidelines, structured dietary programmes) have been developed in an attempt to support healthier and more sustainable eating behaviour [

25]. However, many of the available strategies rely on restriction-based approaches, with limitations for when, how much, and what to eat, and often yield only short-term results, probably because they do not address the underlying factors influencing the individual’s eating behaviour [

26,

27]. On top of this, many people struggle to maintain behavioural change strategies over time [

6], highlighting the need for more research into approaches that support long-lasting change. A growing body of research advocates for alternative, holistic, and health-oriented approaches to dietary behaviour change, that expand the focus beyond restriction and weight loss as the primary means of improving health [

26]. Interoceptive and exteroceptive strategies may represent an approach to supporting healthier eating behaviours, not by imposing restrictions but by fostering greater awareness [

28,

29]. Interoception involves attending to internal bodily states such as hunger, fullness, and pleasure [

2,

30], while exteroception refers to the perception and processing of sensory information originating from outside the body, typically through receptors located in the skin, eyes, ears, nose, and mouth [

31]. In the context of eating behaviour, exteroceptive food-related sensory cues include visual, olfactory, gustatory, auditory, and somatosensory inputs. To avoid conceptual confusion, exteroception is not used here in the sense of external eating or food cue reactivity, which typically describes automatic, cue driven responsivity to environmental stimuli. Though distinct, interoceptive and exteroceptive processes interact and together provide a foundation for regulating eating behaviour [

19,

30,

32]. Importantly, framing eating behaviour through interoceptive and exteroceptive processes may help to specify underlying perceptual and regulatory mechanisms [

28,

33]. Mindful and intuitive eating, by contrast, represent broader approaches that implicitly build on interoceptive and exteroceptive functioning [

9]. Both approaches have been linked to beneficial outcomes, including reduced disordered eating and improved well-being, yet findings across dietary and health outcomes remain inconsistent [

33,

34]. As Tapper (2022) [

33] highlights, a wide range of processes could underline the influence of mindfulness-based practices on eating, but much of the current evidence remains speculative. One possible reason for this inconsistency is that the underlying mechanisms are rarely specified in detail, further complicated by the fact that many of these interventions combine multiple components, making it difficult to determine what actually drives the observed effects [

33]. Without a more precise understanding of these mechanisms, it is difficult to identify which elements are most effective, how they should be adapted to different eating-related challenges, or whether some practices might even prove counterproductive in certain contexts (e.g., weight loss interventions).

By explicitly focusing on perceptual and self-regulatory processes of eating—such as interoceptive and exteroceptive attention—it may be possible to design strategies that strengthen individuals’ ability to sense, interpret, and act on bodily and sensory cues [

28]. This emerging mechanistic perspective helps to clarify the conceptual overlap with mindful and intuitive eating, while also offering a potential pathway toward more precise, testable, and scalable approaches to supporting healthier eating behaviour. Previous research by Palazzo and colleagues (2022) has demonstrated that interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities can be enhanced [

29]. In their research, participants engaged in four 2 h workshops over a period of 3 to 4 weeks, supplemented by inter-session home exercises. From a feasibility perspective, however, it is also important to examine early-stage methods that require less structured time commitment and can be seamlessly integrated into everyday routines, thereby offering a potentially more accessible approach for a wider range of individuals. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that it is possible to direct attention towards interoceptive-, exteroceptive-, and a combination of interoceptive and exteroceptive signals while eating by providing written instructions [

35]. Although the study did not detect an effect on momentary rating on appetite, pleasure and sensory-specific desires, it was hypothesised that this may be due to the study’s design, which included a single-session intervention and thus limited exposure to the attention strategy. Since dietary habits develop over longer timeframes [

36,

37], it is important to explore whether prolonged interoceptive-exteroceptive attention training can yield more sustained changes in eating behaviour.

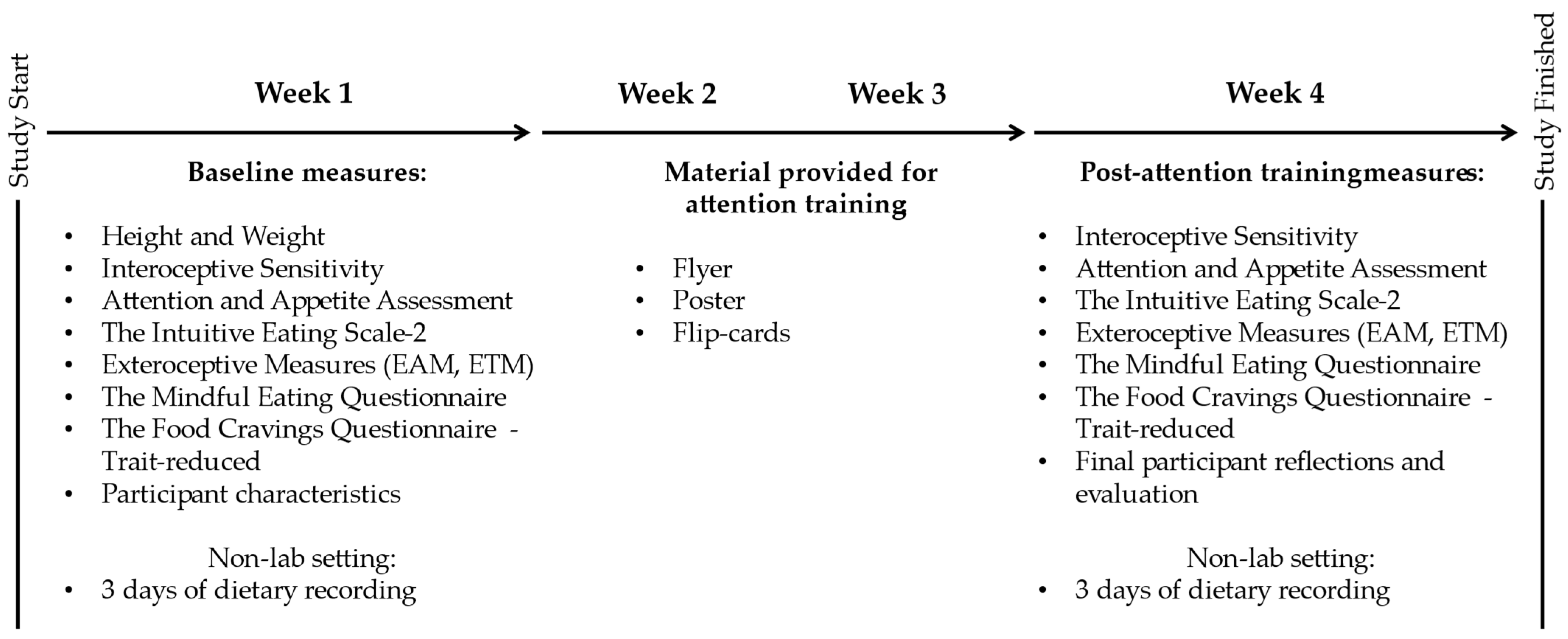

The overall aim of this study was to investigate whether a 14-day interoceptive–exteroceptive attention training programme, delivered through written instructions, could enhance interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities in healthy adults and promote healthier food choices. Specifically, the objectives were to study how the interoceptive-exteroceptive attention training affected: (1) interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities, (2) desire-driven eating, particularly regarding snack food consumption, and (3) the experience of the attention training period.

In the present study, attention training is defined as the systematic, repeated practice of directing attention toward interoceptive (bodily) and exteroceptive (sensory) cues before, during, and after eating episodes. It was hypothesised that a 14-day interoceptive–exteroceptive attention training programme, delivered through flexible and easy-to-use written materials, would enhance attentional focus on bodily (interoceptive) and sensory (exteroceptive) cues and reduce desire-driven eating, particularly the consumption of unhealthy snacks. Finally, it was hypothesised that the study would demonstrate potential for real-world implementation via participants’ experiences with the attention training materials. The hypotheses build on evidence from previous studies, including systematic reviews, indicating that increased attention to internal and external eating-related cues might support more internally regulated eating patterns and healthier food choices [

32,

33]. By supporting participants in becoming more attuned to their bodily sensations and sensory experiences during eating, the attention training was expected to promote greater self-regulation and reduce unhealthy snack consumption.

4. Discussion

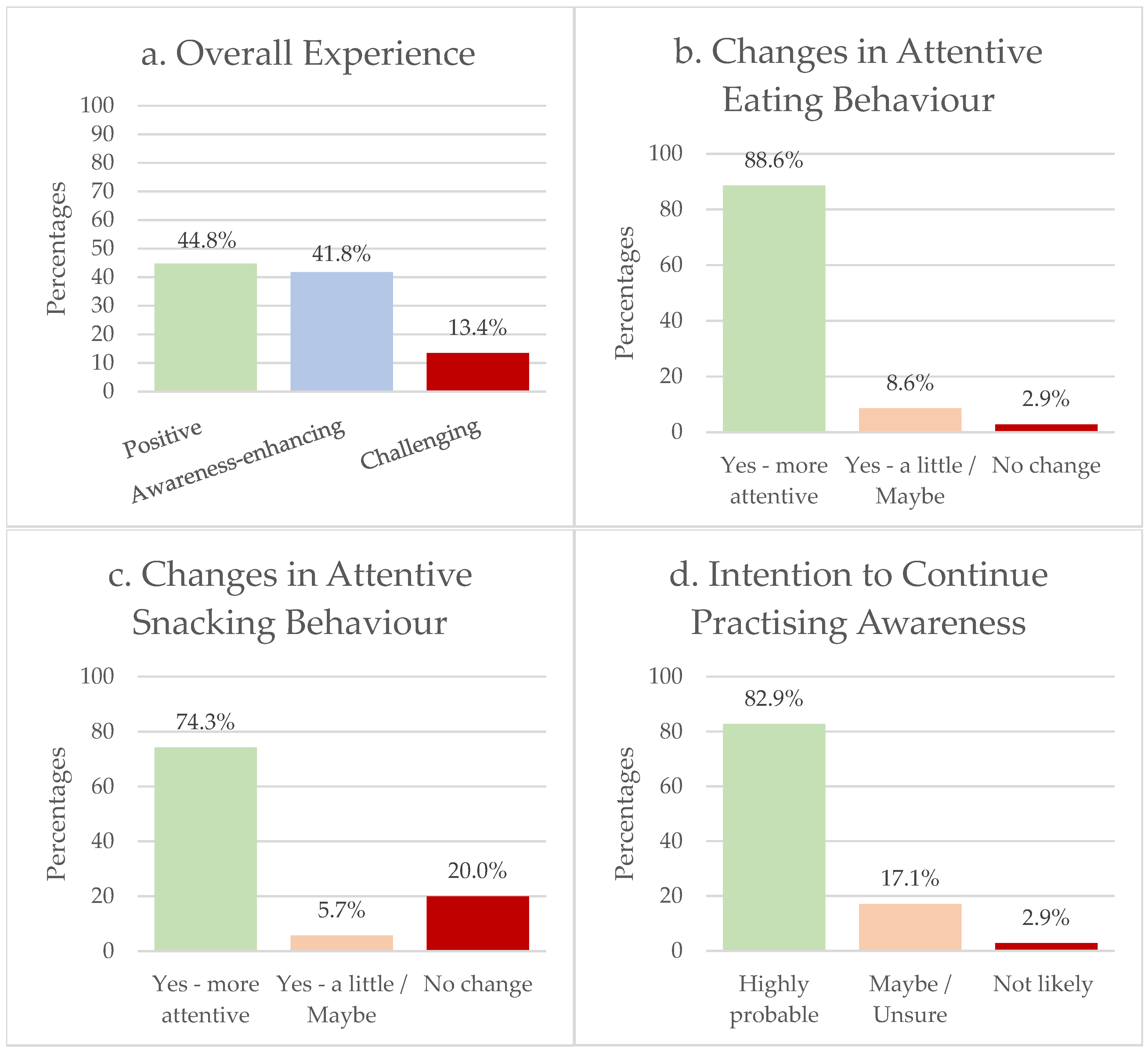

Interoceptive and exteroceptive awareness have been proposed as important processes in the regulation of eating behaviour and may be linked to beneficial health outcomes [

28,

29,

33]. Nevertheless, empirical research on how these abilities can be actively enhanced, and whether such enhancement supports healthier or more sustainable eating behaviours, is still at an early stage. This study examined whether written instructions delivered over a 14-day period could enhance interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities in healthy adults and promote healthier food choices. Specifically, the objectives were to study how the attention training affected: (1) interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities, (2) desire-driven eating, particularly regarding snack food consumption, and (3) the experience of the attention training period. Consistent with the initial expectations, the 14-day period of flexible yet consistent attention training appeared to enhance participants’ interoceptive and exteroceptive abilities. Participants reported significant increases in attention to various sensory experiences, as well as intuitive and mindful eating. A reduction in the consumption of unhealthy snack components was also observed. In post-study evaluations, most participants described the attention training as positive and awareness-enhancing. A large majority reported becoming more attentive in terms of their eating and snacking behaviour, and over 80% intended to continue practising awareness after the study. While not all outcomes reached statistical significance, the overall pattern of results supports the potential of interoceptive-exteroceptive attention strategies as a promising and sustainable approach to promoting healthier and more self-regulated dietary behaviours.

4.1. Interoceptive and Exteroceptive Eating

The present study explored whether a brief period of daily attention training could influence various aspects of eating-related awareness, spanning from internal bodily cues to external sensory inputs. Rather than finding consistent effects across all measures, the results revealed a more differentiated pattern: while several questionnaire-based outcomes showed significant improvements (e.g., intuitive eating, mindful eating and parts of EAM), other task-based measures, such as the HHT and the meal-based attention and appetite assessments, showed only marginal or no effects.

First, participants reported significant improvements in intuitive and mindful eating. Although the attention training focused on a relatively narrow form of interoceptive and sensory attention, these effects were most clearly expressed in broader constructs such as intuitive eating and mindful eating. This aligns with the conceptual scope of these measures, which assess broad patterns of eating awareness, attentional engagement and self-regulated eating behaviour, rather than narrow indices of interoceptive attention. Practising focused attention on bodily and sensory cues, even within specific tasks, may therefore translate into wider changes in how eating episodes are approached and experienced. Previous research has demonstrated that both intuitive and mindful eating can be strengthened through awareness-based strategies, even over relatively short periods [

57,

58,

59,

60], and the present findings indicate that even a brief attention training period may initiate similar shifts in everyday eating behaviour.

The attention training produced clear improvements across several exteroceptive modalities. Participants reported higher attention to taste, texture, temperature, chewing sound and combined sensory features, indicating that the attention training enhanced engagement with sensory properties that are directly experienced during oral processing. These modalities offer vivid, continuous perceptual input while eating, which likely makes them more responsive to short periods of attentional practice. The moderate effect sizes for these domains support this interpretation. By contrast, attention to appearance improved only marginally, and attention to smell and undistracted eating did not change significantly. This pattern suggests that exteroceptive attention is not uniformly malleable and that sensory modalities differ in their trainability. Smell attention showed virtually no change, consistent with evidence that olfactory perception is comparatively resistant to brief mindfulness-based interventions [

61]. Mahmut and colleagues (2021) [

61] reported no significant improvements in objective olfactory accuracy after short-term focused mindfulness practice, and Poellinger and colleagues (2001) [

62] demonstrated that neural responses to odours habituate rapidly during prolonged stimulation. If olfactory processing is characterized by fast habituation and strong top–down influence, it is unsurprising that a short training period did not alter self-reported smell attention. The marginal improvement in appearance attention is also consistent with the idea that visual processing during eating is highly automatized. Visual evaluation of food typically occurs quickly and is strongly shaped by ingrained expectations rather than sustained perceptual monitoring. In everyday eating contexts, visual information is often processed only at the start of the meal, which may limit the degree to which appearance-related attention can be modified through brief training.

Undistracted eating also showed no significant change. This measure reflects a behavioural pattern that depends heavily on environmental and contextual factors rather than on sensory discrimination per se. Since attentional training cannot directly alter the participants’ eating environment, it is reasonable that this outcome would be less responsive than the more proximal oral sensory modalities. The broader pattern aligns with mechanistic evidence from [

63]. Although their study examined neural habituation to visual and olfactory food cues rather than behavioural sensory attention during meals, their findings demonstrate that mindfulness training can modulate how food-related sensory inputs are processed over time. They observed reduced neural habituation in the mindfulness group compared to the control group, suggesting a more sustained responsiveness to sensory stimuli. However, the effects were modest, which is consistent with the idea that visual and olfactory processing are influenced by factors that may require more extended or targeted training to change [

63]. This corresponds with the present findings, where the strongest changes occurred in taste, texture and other oral-sensory modalities, while appearance and smell showed limited change. Overall, these results indicate that exteroceptive attention is multidimensional and that sensory modalities vary in plasticity. Channels that offer immediate and salient perceptual feedback during eating appear to benefit most from brief attentional training, whereas modalities shaped by habitual or contextual factors show more limited change.

The lack of consistent effects across all measures may reflect differences in what each method captures (e.g., questionnaires versus behaviour). This divergence between task-based and questionnaire-based outcomes could also reflect differences in the underlying constructs being assessed: while self-report instruments may tap into more trait-like, generalised aspects of eating-related awareness, tasks such as the HHT or the meal-based ratings capture more state-dependent, momentary fluctuations. These latter outcomes may be more vulnerable to situational noise [

64,

65] or insufficient exposure duration, which prevents the integration of attentional shifts into moment-to-moment experiences. Although the HHT did not show significant improvement, there was a slight numerical increase in performance. This marginal improvement may indicate an emerging trend toward improved interoceptive sensitivity, although it is too small or variable to reach statistical significance in the current sample. In this sense, it aligns directionally with the questionnaire-based findings and suggests that even brief attention training may begin to influence interoceptive processing, though more sustained practice or larger samples may be needed for robust effects to manifest, as seen in the intervention carried out by [

29]. The absence of significant change in the HHT, in particular, should be interpreted cautiously. Interoceptive sensitivity, as assessed by heartbeat perception tasks, has been criticised for its limited validity and vulnerability to non-interoceptive influences such as prior knowledge or cognitive estimations [

66]. Thus, the marginal improvement observed cannot be taken as evidence of meaningful interoceptive change, but it also does not rule out the possibility, particularly in light of the behavioural shift in snack consumption and the improvements in self-reported intuitive and mindful eating. In this study, the HHT results are therefore best understood as preliminary signals rather than indicators of established or clinically relevant change. Future studies with longer attention training periods, larger samples and repeated assessments are needed to determine whether such early shifts can accumulate into more robust outcomes.

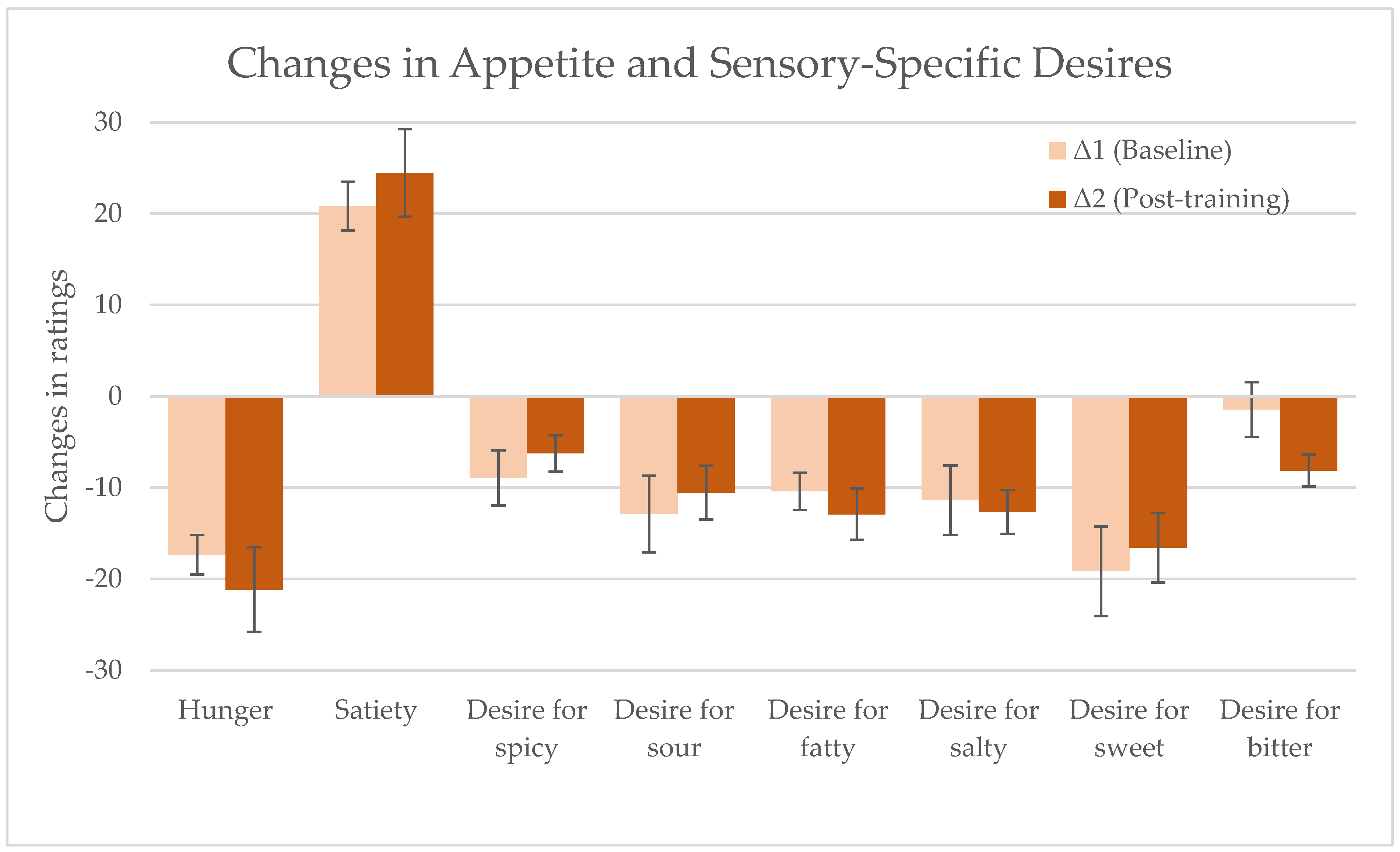

Similarly, participants’ attention responses during the test meal showed small and non-significant changes. This contrasts with findings by Palazzo and colleagues (2022) [

29], who used a comparable task and reported clearer effects, although their study focused exclusively on exteroception in that task. The marginal changes observed in the present study may suggest that participants had begun to apply attentional strategies during eating, but that the duration of the training was not sufficient for these shifts to consolidate into more stable changes. This distinction aligns with the framework by Chun et al., (2011) [

41], who emphasise that while attention can be effectively directed through instructions or training, it does not always lead to conscious awareness capable of altering behaviour. In this context, the observed changes in questionnaire-based outcomes (e.g., intuitive eating, mindful eating and parts of EAM) may reflect an initial stage of attentional shift. In contrast, behavioural tasks, like the HHT and the attention assessment, might require a more sustained transition into conscious awareness to register measurable effects. Theoretical insights from Chun et al. (2011) [

41] may help interpret these findings. They distinguish between attention (the selective direction of cognitive resources) and awareness, which involves deeper conscious processing. According to their framework, sustained and repeated attentional engagement is typically required for attentional focus to evolve into awareness capable of altering behaviour. In this study, even a brief attentional training period appears to have initiated such a shift, as indicated by reductions in unhealthy snacking. This suggests that awareness may not be an all-or-nothing state but rather exists on a continuum, where partial or emerging awareness can still support meaningful behavioural outcomes.

Taken together, the results indicate that even brief and accessible attention training can begin to shape individuals’ eating-related awareness, particularly at the level of general tendencies and self-perceived behaviour. While more situational, performance-based measures may require longer or more intensive attention training to capture meaningful changes, these findings highlight the potential of everyday-compatible attentional practices. The marginal improvements in HHT performance and meal-based assessments, although not statistically robust, are noteworthy because they point in the same direction as the stronger questionnaire-based changes. This convergence suggests that the attention training period may have initiated subtle attentional shifts at both trait-like and state-dependent levels. Future studies with longer interventions, larger samples, including control groups, and repeated state-level assessments will be crucial to determine whether such small shifts can consolidate into stable behavioural and physiological changes. Future studies should further explore how duration, repetition, and contextual embedding influence the transition from attentional focus to embodied awareness and, ultimately, to sustainable changes in eating behaviour in the long term. These present findings challenge the assumption that only long-term or intensive interventions are capable of modifying eating behaviour. Instead, the present findings suggest that even brief interoceptive-exteroceptive attention strategies might contribute to changes in eating behaviour and engagement with bodily and sensory cues in real-world contexts. Future research should examine whether extending the attention training period further enhances this transition from attentional focus to sustained behavioural change and whether such shifts are maintained over time.

4.2. Desire-Driven Eating Behaviour and Snack Consumption

Recognising that eating is not solely governed by hunger and satiety cues [

67], the present study also targeted desire- or craving-driven eating. Importantly, a significant reduction in the number of unhealthy snack components was observed following the attention training period. This shift suggests that participants may have become more aware of their snack choices, potentially favouring options more aligned with internal cues such as hunger, fullness, or physiological need rather than acting on habit, emotions, cravings, or convenience. This interpretation is consistent with previous findings linking intuitive eating to healthier dietary patterns, reduced emotional eating, and less overeating [

9,

68,

69]. Further support for this interpretation comes from the growing literature on sensory awareness during eating. For example, prolonged oro-sensory exposure (i.e., the experience of food in the mouth) has been shown to decrease later snack intake [

70]. A recent review by Lasschuijt and colleagues (2021) underscores that enhancing sensory attention may support appetite regulation and contribute to healthy weight maintenance [

71].

In addition to changes in snack composition, a marginal reduction in food cravings was observed, as measured by the FCQ-T-r, from baseline to post-attention training (

p = 0.069, d = 0.32). Although this change did not reach statistical significance, the small effect size may indicate a trend toward reduced cravings. Recent evidence indicates that cognitive as well as mindfulness oriented programmes may enhance this form of regulation, showing benefits for craving intensity, eating patterns, and in some cases also weight outcomes [

72,

73]. Viewed in this context, the marginal craving reduction in the present study fits the broader pattern of findings: small attentional shifts may be sufficient to initiate early changes in craving-related processes, even if they do not yet reach statistical significance. Taken together with the reduction in unhealthy snack components, this suggests that attention training may influence craving-related aspects of eating behaviour.

Future studies with longer or more intensive training periods may be better suited to detect more robust effects, as meaningful changes in dietary habits often require sustained effort over time [

74]. Given that food cravings commonly influence eating behaviour [

8,

75] and have been linked to increased food intake and subsequent weight gain [

8], reducing the impact through enhanced attention to bodily and sensory cues holds promise. This is particularly relevant when cravings are directed toward energy-dense, nutrient-poor snack products, which are typically high in fat, salt, and/or sugar yet low in essential nutrients such as dietary fibre, vitamins, and minerals [

73].

A potential conceptual concern is that enhancing exteroceptive attention could be mistaken for increasing sensitivity to external food cues, which, in the case of external eating, has been associated with overeating [

75]. In the present study, however, exteroception was conceptualised differently: as deliberate attention to the sensory qualities of food during eating (e.g., taste, texture, temperature), rather than automatic reactivity to environmental cues such as advertising or availability. This distinction is important, as studies indicate that paying attention to food intake and enhancing memory of meals can increase satiety and reduce subsequent intake [

20,

21,

32]. Thus, rather than amplifying cue reactivity, exteroceptive attention training may help anchor attention to the eating episode itself and support more regulated eating. Given the very early exploratory stage of this research, it remains crucial to investigate whether some individuals may benefit more from interoceptive attention training, while others may benefit more from exteroceptive approaches. Taken together, these findings contribute to the growing body of evidence suggesting that attention-based practices, particularly those focused on bodily signals and sensory experiences, may support healthier eating behaviours in ways that are easier to integrate into everyday life.

4.3. Interoceptive and Exteroceptive Attention Training: Potential for Real-World Implementation

Overall, the attention training, delivered through written materials guiding participants’ focus, demonstrated promising potential as a tool for enhancing attention related to eating. When asked about their overall experience, participants generally described the attention training as positive and awareness-enhancing. Furthermore, the majority expressed a strong likelihood of continuing to practise the techniques they had learned, suggesting that such strategies may be both acceptable and sustainable in the longer term. Importantly, these findings underscore the real-world applicability of flexible, scalable approaches designed to enhance bodily and sensory attention. One likely reason for this positive reception is the programme’s simplicity. The attention training was designed as a set of flexible, easy-to-use materials, requiring little time investment and intended to be integrated into everyday routines without restricting when, how, or what individuals eat. This low-burden, self-administered format was intended to offer an alternative to more complex, multi-component approaches and may represent a pathway to supporting conscious and healthier food choices. Its simplicity and flexibility suggest potential for broader uptake and longer-term behavioural impact. At the same time, long-term feasibility remains an open question, as adherence may decline without ongoing support or reinforcement [

6]. There is also potential to integrate this approach into larger multi-component interventions, where attentional strategies could complement other behavioural or lifestyle components. Such integration may help clarify whether the unique contribution of interoceptive–exteroceptive attention training lies in its standalone simplicity, or in the added value it might provide as part of more comprehensive programmes. Taken together, the present findings point to the relevance of further exploring this attentional approach, particularly with regard to its effectiveness and scalability in real-world settings.

4.4. Limitations

Several methodological considerations should be noted when interpreting the findings. Most importantly, the study employed a single-group pre–post design without randomisation, control groups or blinded procedures. While participants served as their own control, this design limits the ability to draw strong causal conclusions about the effectiveness of the attention training. The absence of a blank control group (i.e., participants completing only pre- and post-tests without exposure to the materials) means that environmental or repeated-testing effects cannot be excluded. Similarly, the lack of an experimental control group receiving, e.g., non-eating-related material, prevents us from ruling out expectancy or experimenter effects. Furthermore, no blinding procedures were implemented, and participants were aware that the study concerned eating behaviour, which may have influenced their responses. Taken together, these design limitations raise the possibility that some of the observed changes could be attributable to placebo or demand characteristics rather than the attention training itself.

While the 14-day attention training period may be considered relatively short, it was due to prior research interventions [

43], which hypothesised that it would be sufficient to induce measurable changes in attention-related eating behaviour. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the duration of the attention training and the frequency at which the written material was used affected the results. In this study, the duration was chosen to balance ecological validity, participant compliance, and the goal of integrating attentional strategies into everyday meals without imposing extensive demands. Future studies could, however, explore the effects of longer attention training periods, as evidence suggests that the formation of new habits can take, on average, over two months of repeated behaviour in a consistent context to reach automaticity [

36].

A further limitation relates to the delivery of the attention training materials outside controlled laboratory settings. Participants were instructed to read the poster daily and use the flip-cards every second day during a main meal. As a procedural check, participants also indicated how often they had used each material. Reported adherence was generally high (

Table S3), with the majority using flip-cards every second day as instructed, and most participants reading the poster at least every second day. However, because these data were self-reported and the study took place in everyday environments, it cannot be certain about the accuracy of reported frequencies, the duration of use, or whether the materials were applied as intended in relation to meals. Such variability in engagement may have introduced heterogeneity to the extent to which the attentional strategies were practised. Future studies could address this by implementing more standardised delivery modes or by monitoring adherence more closely.

Another limitation concerns statistical power. Although an a priori power analysis was conducted, the present pre–post (within-subjects) design was not powered to detect small effects with high certainty. For a two-time-point within-subjects comparison, achieving power of 0.90 to detect a medium effect (Cohen’s dz ≈ 0.50) would typically require on the order of 40–45 participants, with larger samples needed for smaller effects. Thus, some null findings should be interpreted with caution. Future studies should aim for larger samples and, where appropriate, include additional measurement occasions or control groups to increase precision and internal validity.

Finally, the sample characteristics may limit the generalisability of the findings. Participants were Danish citizens and generally healthy, with normal BMI and regular engagement in physical activity, suggesting a relatively health-conscious and culturally homogeneous sample. This restricts the applicability of the results to broader populations, including individuals at higher risk for diet-related health problems or with less consistent health behaviours. To improve external validity, future studies should recruit more heterogeneous samples and assess whether attentional training strategies are equally effective across diverse health profiles and cultural contexts. Taken together, these limitations call for caution in interpreting the findings. At the same time, the study provides valuable proof-of-concept evidence that interoceptive-exteroceptive attention strategies can be implemented in everyday settings, offering a foundation for more rigorous future trials.