Relationships Among Psychological Risk, Eco-Friendly Packaging, Price Fairness, and Brand Trust of Bottled Water Consumers: Moderating the Impact of Nutritional Disclosure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Psychological Risk

2.2. Eco-Friendly Packaging

2.3. Price Fairness

2.4. Brand Trust

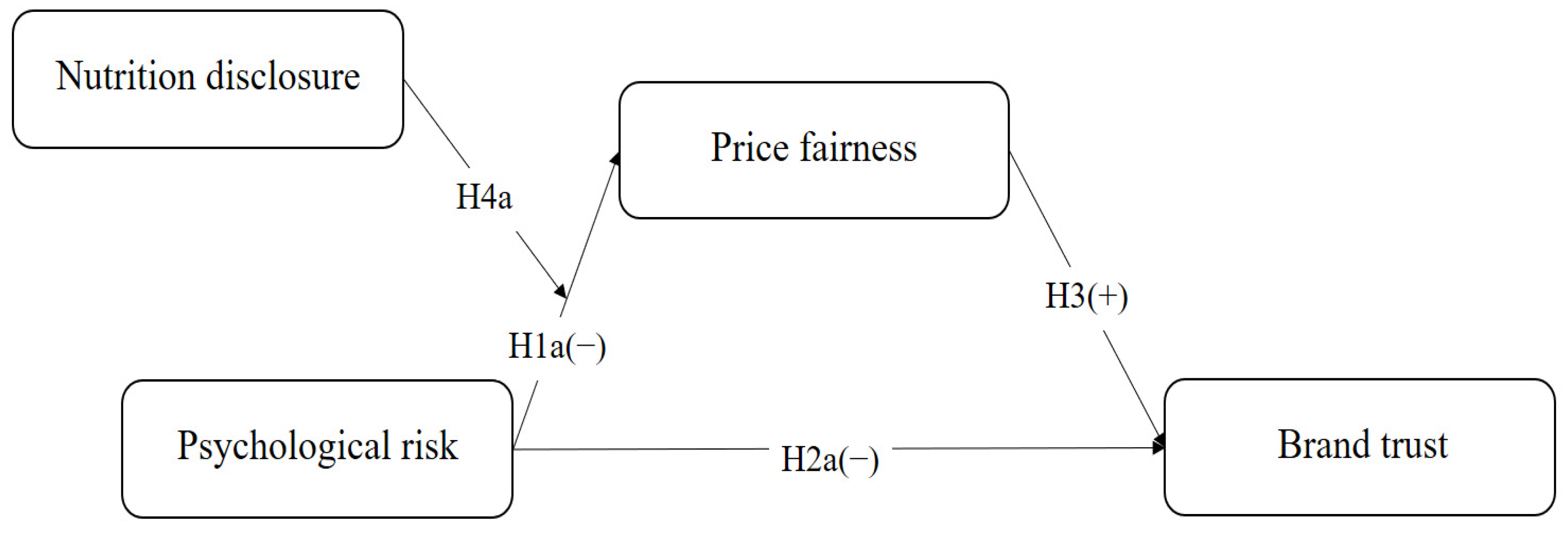

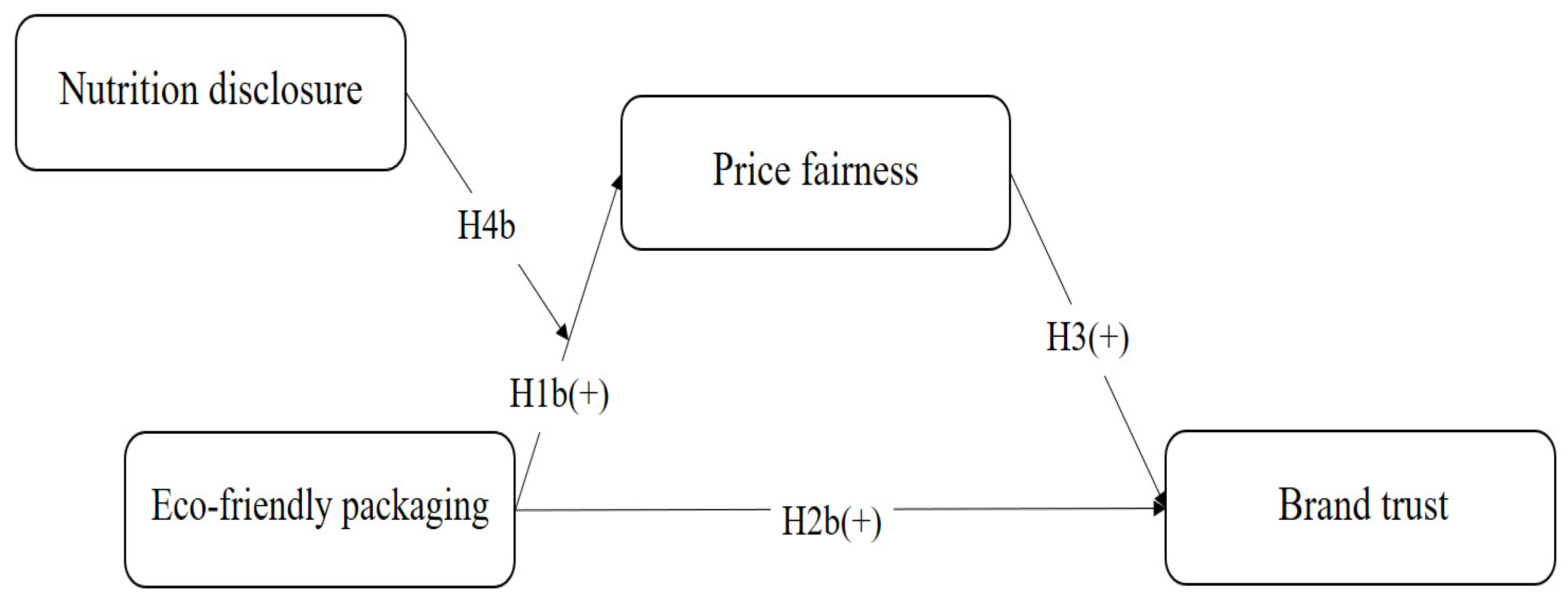

2.5. Hypothesis Development

2.6. Nutritional Disclosure

3. Methods

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement Items

3.3. Recruitment of Participants

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis and Reliability Testing

4.2. Correlation Matrix and Descriptive Statistics

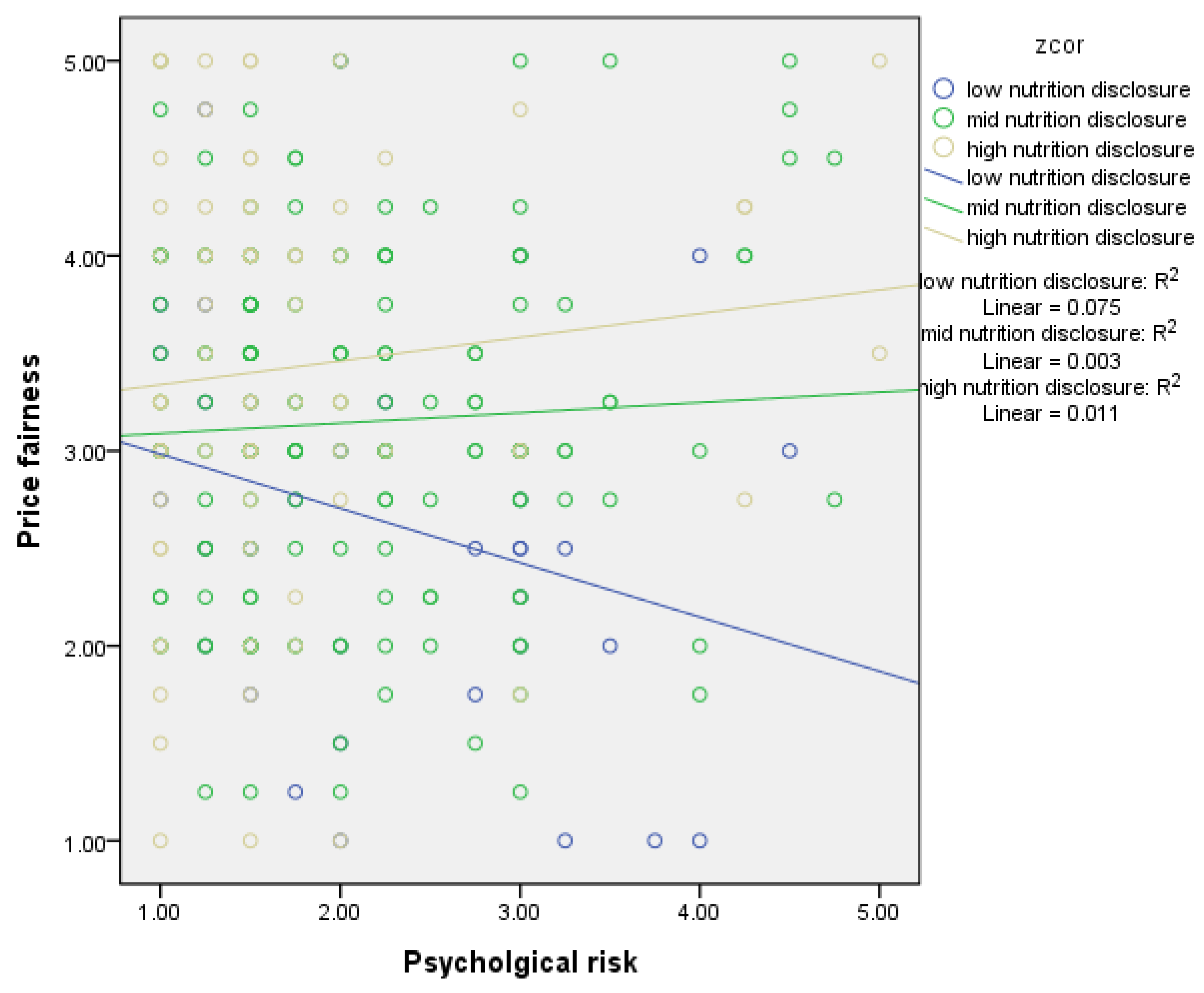

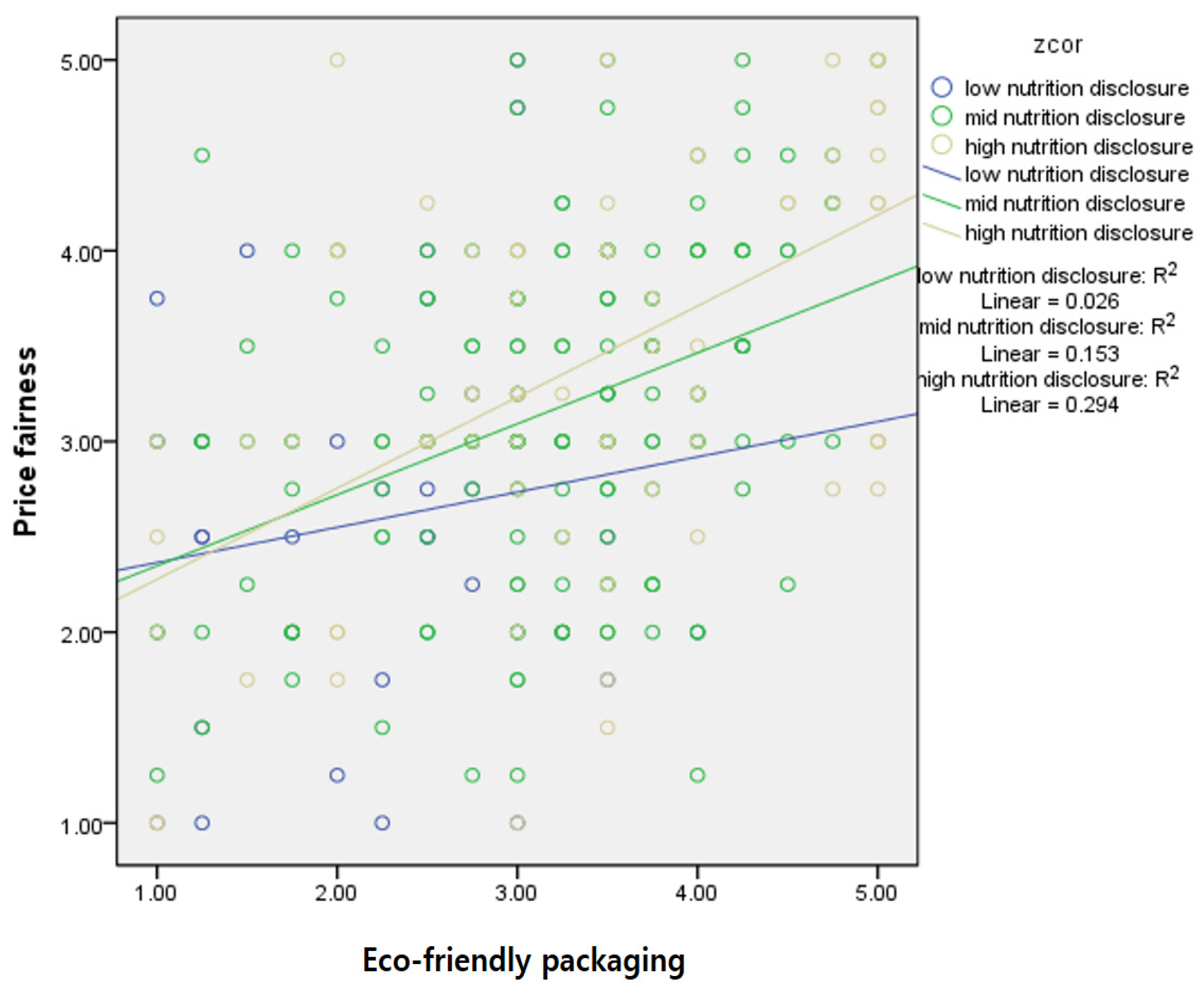

4.3. Results of Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grand View Research. Market Analysis Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/bottled-water-market (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Statista. The Global Giants of the Bottled Water Business. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/31772/leading-bottled-water-brands-by-global-market-share (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Sembiring, C.; Azis, I.; Pradika, F. Analysis of brand awareness, customer satisfaction and perceived quality on the brand loyalty in the bottled water consumer (AMDK) Sinarmas Pristine Brand. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Atulkar, S. Brand trust and brand loyalty in mall shoppers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H.E.; Özbek, O. The effect of brand experiences on brand loyalty through perceived quality and brand trust: A study on sports consumers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 2130–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.R.; Kim, S.E. Effect of brand experiences on brand loyalty mediated by brand love: The moderated mediation role of brand trust. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2412–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, L.E.; Keh, H.T.; Alba, J.W. How do price fairness perceptions differ across culture? J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Hao, F.; Liu, S. Service quality, perceived price fairness, and users’ continuous usage intentions regarding shared bike service. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2023, 34, 1682–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Cho, H.J.; Jin, B.E. Does effective cost transparency increase price fairness? An analysis of apparel brand strategies. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Slack, N.J.; Sharma, S.; Aiyub, A.S.; Ferraris, A. Antecedents and consequences of fast-food restaurant customers’ perception of price fairness. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2591–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Elshaer, I.A. Examining the influence of trust and perceived risk on customers intention to use NFC mobile payment system. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, A. The effect of halal product knowledge, halal awareness, perceived psychological risk and halal product attitude on purchasing intention. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 13, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H.; Lee, J.H. The emergence of service robots at restaurants: Integrating trust, perceived risk, and satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. Trust and risk perception: A critical review of the literature. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging—A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Frommeyer, B.; Schewe, G. Managing the transition to eco-friendly packaging–An investigation of consumers’ motives in online retail. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 351, 131504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Cronin, J.J.; Peloza, J. The role of corporate social responsibility in consumer evaluation of nutrition information disclosure by retail restaurants. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.J.; George, T. Nutritional information disclosure on the menu: Focusing on the roles of menu context, nutritional knowledge and motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S. Restaurants’ disclosure of nutritional information as a corporate social responsibility initiative: Customers’ attitudinal and behavioral responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Neguriţă, O.; Grecu, I.; Grecu, G.; Mitran, P.C. Consumers’ decision-making process on social commerce platforms: Online trust, perceived risk, and purchase intentions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Parker, L.; Brennan, L.; Lockrey, S. A consumer definition of eco-friendly packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorineschi, L.; Conti, L.; Rossi, G.; Rotini, F. Conceptual design of a small production plant for eco-friendly packaging. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 22, 1257–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Alaimo, L.S.; Ciaccio, T.; Vrontis, D.; Fiore, M. Plastic or not plastic? That’s the problem: Analysing the Italian students purchasing behavior of mineral water bottles made with eco-friendly packaging. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Yến-Khanh, N.; Thuan, N.H. Consumers’ purchase intention and willingness to pay for eco-friendly packaging in Vietnam. In Sustainable Packaging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 289–323. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.R.; Hsieh, S.; Ricacho, N. Innovative food packaging, food quality and safety, and consumer perspectives. Processes 2022, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Han, H. Building value co-creation with social media marketing, brand trust, and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M.; Rong, L.; Ali, M.; Alam, S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Ali, K. The mediating role of brand trust and brand love between brand experience and loyalty: A study on smartphones in China. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Xu, X. Exploring bottled water purchase intention via trust in advertising, product knowledge, consumer beliefs and theory of reasoned action. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Wang, X. Effects of logistics service quality and price fairness on customer repurchase intention: The moderating role of cross-border e-commerce experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. Trustworthy brand signals, price fairness and organic food restaurant brand loyalty. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 3035–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, E.Y. The effect of perceived risk on online shopping in Jordan. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ventre, I.; Kolbe, D. The impact of perceived usefulness of online reviews, trust and perceived risk on online purchase intention in emerging markets: A Mexican perspective. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B.; Cha, H.S. The mediating role of consumer trust in an online merchant in predicting purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.; Kim, S.; Seo, D.; Lee, S. Effects of explanation types and perceived risk on trust in autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 73, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.H. The effects of perceived risk, brand credibility and past experience on purchase intention in the Airbnb context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadha, H.; Suparna, G. The Role of Brand Trust Mediates the Effect of Perceived Risk and Brand Image on Intention to Use Digital Banking Service. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 7, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Raza, S.A.; Khamis, B.; Puah, C.H.; Amin, H. How perceived risk, benefit and trust determine user Fintech adoption: A new dimension for Islamic finance. Foresight 2021, 23, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hride, F.T.; Ferdousi, F.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Linking perceived price fairness, customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: A structural equation modeling of Facebook-based e-commerce in Bangladesh. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutama, K.Y.; Ekawati, N.W. The influence of price fairness and corporate image on customer loyalty towards trust. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 4, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chubaka Mushagalusa, N.; Balemba Kanyurhi, E.; Bugandwa Mungu Akonkwa, D.; Murhula Chubaka, P. Measuring price fairness and its impact on consumers’ trust and switching intentions in microfinance institutions. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2022, 27, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.C.; Burton, S.; Netemeyer, R.G. Are some comparative nutrition claims misleading? The role of nutrition knowledge, ad claim type and disclosure conditions. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seenivasan, S.; Thomas, D. Negative consequences of nutrition information disclosure on consumption behavior in quick-casual restaurants. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, E.; Hall, M.; Carpentier, F.; Musicus, A.; Meyer, M.L.; Rimm, E.; Taillie, L. Nutrition claims on fruit drinks are inconsistent indicators of nutritional profile: A content analysis of fruit drinks purchased by households with young children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Humphreys, G.; Jones, A. Alcohol, calories, and obesity: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of consumer knowledge, support, and behavioral effects of energy labeling on alcoholic drinks. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.A.; Moon, J. Relationships between psychological risk, brand trust, and repurchase intentions of bottled water: The moderating effect of eco-friendly packaging. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maar, D.; Besson, E.; Kefi, H. Fostering positive customer attitudes and usage intentions for scheduling services via chatbots. J. Serv. Manag. 2023, 34, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racat, M.; Plotkina, D. Sensory-enabling technology in m-commerce: The effect of haptic stimulation on consumer purchasing behavior. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2023, 27, 354–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalul Ariffin, S.; Mohan, T.; Goh, Y.N. Influence of consumers’ perceived risk on consumers’ online purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Chou, C.; Vighnesh, N.; Chandrashekar, D. Understanding post-pandemic market segmentation through perceived risk, behavioural intention, and emotional wellbeing of consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103482. [Google Scholar]

- Konuk, F.A. Price fairness, satisfaction, and trust as antecedents of purchase intentions towards organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Brand trust | BT1 | I trust the brand Dasani. |

| BT2 | Dasani is reliable. | |

| BT3 | Dasani is credible. | |

| BT4 | Dasani is trustworthy. | |

| Price fairness | PF1 | The price of Dasani goods is fair. |

| PF2 | The price of Dasani goods is rational. | |

| PF3 | The price of Dasani goods is reasonable. | |

| PF4 | The price of Dasani goods is acceptable. | |

| Nutritional disclosure | ND1 | Dasani offers ingredient information. |

| ND2 | Dasani discloses its ingredients. | |

| ND3 | Dasani water is presented well. | |

| ND4 | Dasani provides me with ingredient information. | |

| Psychological risk | PR1 | Dasani is psychologically risky. |

| PR2 | Dasani is risky to consume. | |

| PR3 | Dasani causes uncertainty. | |

| PR4 | Dasani did not meet my expectations. | |

| Eco-friendly packaging | EP1 | Dasani packaging is environmentally friendly. |

| EP2 | Dasani packaging is eco-friendly. | |

| EP3 | Dasani packaging is recyclable. | |

| EP4 | Dasani packaging is useful to reduce plastic garbage. |

| Demographics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 84 | 27.3 |

| Female | 224 | 72.4 |

| Employed | 212 | 68.8 |

| Unemployed | 96 | 31.2 |

| 20 s | 57 | 18.5 |

| 30 s | 106 | 34.4 |

| 40 s | 104 | 33.8 |

| 50 s | 33 | 10.7 |

| ≥60 years old | 8 | 2.6 |

| Monthly household income | 98 | 31.8 |

| <$2500 | 105 | 34.1 |

| $2500–$4999 | 57 | 18.5 |

| $5000–$7499 | 48 | 15.6 |

| >$7500 |

| Variable | Code | Loading | Cronbach’s α | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand trust | BT1 | 0.825 | 0.950 | 7.699 | 38.495 |

| BT2 | 0.842 | ||||

| BT3 | 0.835 | ||||

| BT4 | 0.832 | ||||

| Price fairness | PF1 | 0.825 | 0.930 | 3.295 | 16.475 |

| PF2 | 0.852 | ||||

| PF3 | 0.886 | ||||

| PF4 | 0.877 | ||||

| Nutritional disclosure | ND1 | 0.884 | 0.916 | 2.163 | 10.816 |

| ND2 | 0.904 | ||||

| ND3 | 0.716 | ||||

| ND4 | 0.911 | ||||

| Psychological risk | PR1 | 0.905 | 0.865 | 1.347 | 6.737 |

| PR2 | 0.923 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.882 | ||||

| PR4 | 0.600 | ||||

| Eco-friendly packaging | EP1 | 0.865 | 0.882 | 1.593 | 7.967 |

| EP2 | 0.876 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.634 | ||||

| EP4 | 0.840 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand trust | 3.508 | 1.093 | 1 | ||||

| Price fairness | 3.152 | 0.941 | 0.519 * | 1 | |||

| Nutritional disclosure | 3.804 | 0.899 | 0.485 * | 0.297 * | 1 | ||

| Psychological risk | 1.995 | 0.918 | −0.233 * | −0.024 | −0.188 * | 1 | |

| Eco-friendly packaging | 3.115 | 1.009 | 0.490 * | 0.457 * | 0.353 * | 0.063 |

| Model 1 Price Fairness | Model 2 Brand Trust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-value | β | t-value | |

| Constant | 3.236 | 6.14 * | 2.149 | 9.99 * |

| Psychological risk | −0.627 | −2.74 * | −0.262 | −4.65 * |

| Nutritional disclosure | −0.030 | −0.23 | ||

| Interaction | 0.172 | 2.98 * | ||

| Price fairness | 0.597 | 10.86 * | ||

| F-value | 13.15 * | 71.10 * | ||

| R2 | 0.1149 | 0.3180 | ||

| Conditional effect of the focal predictor | β | t-value | ||

| Nutritional disclosure | ||||

| 3.00 (Low) | −0.109 | −1.48 | ||

| 4.00 (Mid) | 0.063 | 1.10 | ||

| 5.00 (High) | 0.235 | 2.67 * | ||

| Mediated moderation effect | Index | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0.1031 * | 0.0282 | 0.1805 | ||

| Model 3 Price Fairness | Model 4 Brand Trust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-value | β | t-value | |

| Constant | 2.363 | 4.37 * | 1.063 | 5.38 * |

| Eco-friendly packaging | 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.346 | 6.15 * |

| Nutritional disclosure | −0.092 | −0.67 | ||

| Interaction | 0.093 | 2.01 * | ||

| Price fairness | 0.433 | 7.19 * | ||

| F-value | 31.99 * | 82.17 * | ||

| R2 | 0.2400 | 0.3502 | ||

| Conditional effect of the focal predictor | β | t-value | ||

| Nutritional disclosure | ||||

| 3.00 (Low) | 0.281 | 4.13 * | ||

| 4.00 (Mid) | 0.374 | 7.52 * | ||

| 5.00 (High) | 0.467 | 6.90 * | ||

| Mediated moderation effect | Index | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0.0404 | −0.0072 | 0.0893 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.-A.; Moon, J. Relationships Among Psychological Risk, Eco-Friendly Packaging, Price Fairness, and Brand Trust of Bottled Water Consumers: Moderating the Impact of Nutritional Disclosure. Foods 2024, 13, 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13233800

Sun K-A, Moon J. Relationships Among Psychological Risk, Eco-Friendly Packaging, Price Fairness, and Brand Trust of Bottled Water Consumers: Moderating the Impact of Nutritional Disclosure. Foods. 2024; 13(23):3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13233800

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kyung-A, and Joonho Moon. 2024. "Relationships Among Psychological Risk, Eco-Friendly Packaging, Price Fairness, and Brand Trust of Bottled Water Consumers: Moderating the Impact of Nutritional Disclosure" Foods 13, no. 23: 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13233800

APA StyleSun, K.-A., & Moon, J. (2024). Relationships Among Psychological Risk, Eco-Friendly Packaging, Price Fairness, and Brand Trust of Bottled Water Consumers: Moderating the Impact of Nutritional Disclosure. Foods, 13(23), 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13233800