Factors Driving Individuals’ Attitudes toward Sugar and Sweet-Tasting Foods: An Analysis within the Scope of Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Evaluation of Factors Affecting Sugar Intake Behavior

2.3. Evaluation of Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics and Health Status

2.4. Sugar Intake Estimation

2.5. Evaluation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Intake

2.6. Statistical Analysis

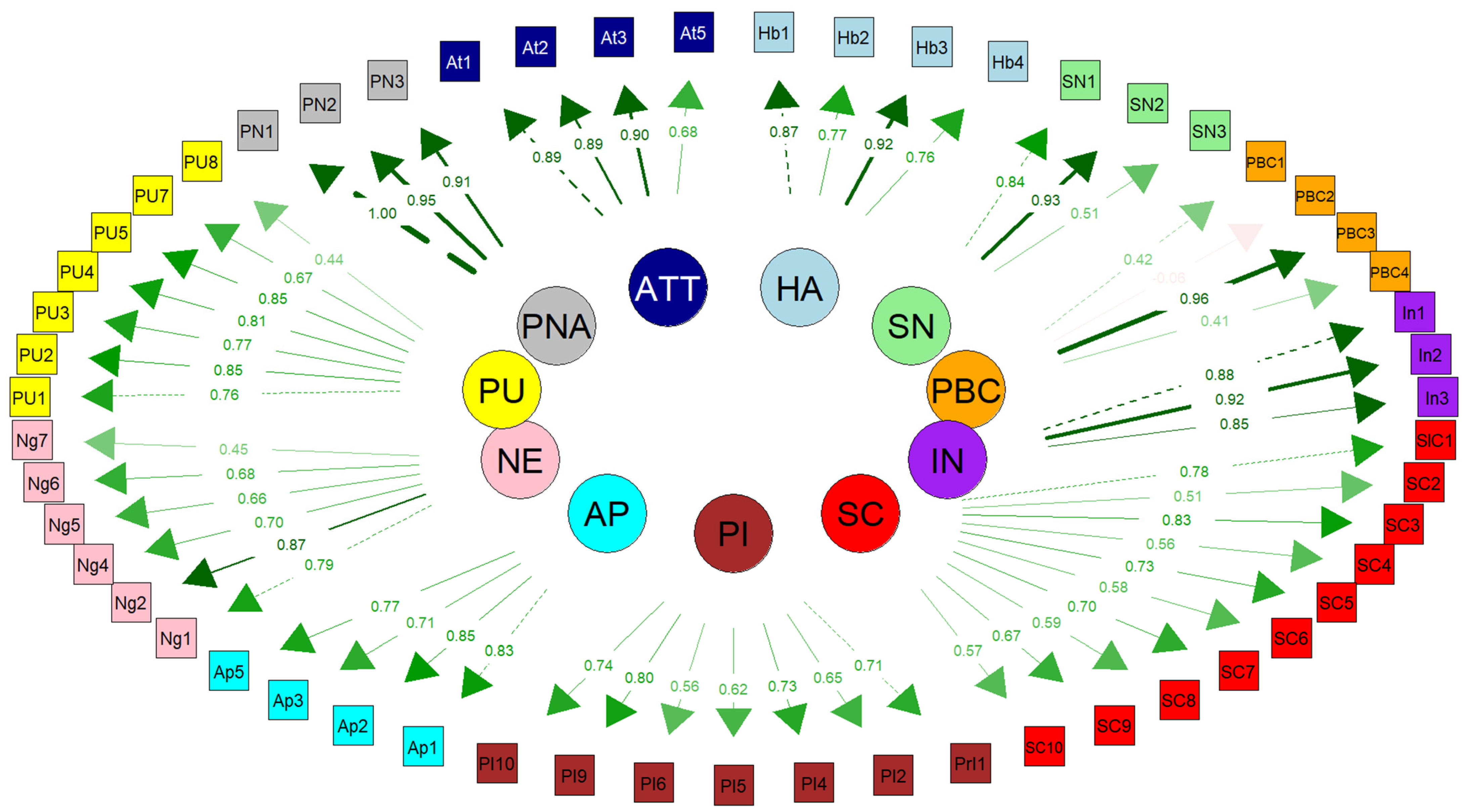

| Variable | Items |

|---|---|

| Habit [30] | HA1: consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet is something I automatically perform. HA2: consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet is something I perform without having to consciously remember. HA3: consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet is something I perform without thinking. HA4: consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet is something I start to perform before I realize I am performing it. |

| Subjective norm [19] | SN1: most individuals who are significant to me would approve of me consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. SN2: most individuals whose opinions I value believe that I should consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. SN3: most individuals who are significant to me are consuming foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of their daily diet. |

| Perceived behavioral control [19,31] | PBC1: it is mostly up to me whether I consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. PBC2: it would be possible for me to consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. PBC3: I have complete control over whether I consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. PBC4: if I wanted to, I could easily consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet. |

| Intention [19] | IN1: I intend to consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet in the next month. IN2: I expect to consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet in the next month. IN3: it is likely that I will consume foods and drinks high in free sugar as part of my daily diet in the next month. |

| Self-control [32] | SC1: I have difficulty starting tasks. SC2: I immediately perform my chores. SC3: I find it difficult to get down to work. SC4: I am always prepared. SC5: I frequently waste my time. SC6: I start tasks right away. SC7: I tend to postpone decisions. SC8: I like to get to work at once. SC9: I need a push to get started. SC10: I tend to carry out my plans. |

| Personal impact [16] | PI1: I tend to crave sweet foods. PI2: I tend to crave sugars. PI3: I tend to crave sweeteners (removed). PI4: I want to reduce my sweet food intake. PI5: the presence or absence of sweet foods in my diet influences my mood. PI6: the presence or absence of sugars in my diet influences my mood. PI7: the presence or absence of sweeteners in my diet influences my mood (removed). PI8: I feel indifferent toward sweet foods. PI9: the sweet taste is physically addictive. PI10: sugar is physically addictive. |

| Personal management [16] | PM1: when I consume sugars, I balance out my diet through exercising and/or eating other healthy foods. PM2: when I consume sweeteners, I balance out my diet through exercising and/or eating other healthy foods. PM3: when I consume sweet foods, I balance out my diet through exercising and/or eating other healthy foods. PM4: my preference and/or intake of sugars depends on how much knowledge I have on them. PM5: my preference and/or intake of sweeteners depends on how much knowledge I have on them. PM6: I only consume sweet foods during special occasions. PM7: I only consume sugars during special occasions. PM8: I only consume sweeteners during special occasions. PM9: I categorize my sweet food intake into either “special” or “normal”. PM10: my health or body image will determine whether I modify my sugar intake or not. PM11: my health or body image will determine whether I modify my sweet food intake or not. PM12: my health or body image will determine whether I modify my sweetener intake or not. PM13: individuals who I am with (family, friends, and colleagues) influence my sweetener intake (removed). |

| Apathy [16] | AP1: individuals are highly concerned about cutting down on sweet foods. AP2: individuals are highly concerned about cutting down on sugars. AP3: individuals are highly concerned about cutting down on sweeteners. AP4: sugar is not as bad as fat for your health (removed). AP5: adding sugar in food products is unnecessary. |

| Negativity [16] | NE1: sweeteners are worse for your health than salt. NE2: sweeteners are physically addictive. NE3: sweeteners are not as bad as fat for your health (removed). NE4: adding sweeteners in food products is unnecessary. NE5: I feel guilty whenever I consume sweeteners. NE6: labels are misleading and deceptive. NE7: the food environment hinders me from reducing my sweetener intake. |

| Perceived understanding [14] | PU1: I know where to find credible information on sugars. PU2: I know where to find credible information on sweet foods. PU3: I know where to find credible information on sweeteners. PU4: If someone asks me, “what are sweeteners?”, I can explain. PU5: If someone asks me, “what is sugar?”, I can explain. PU6: I do not know whether to consume sugars or sweeteners (removed). PU7: I know how to replace sugars with sweeteners in cooking/baking. PU8: I know what strategies or policies have been implemented for reducing sugar intake in Turkiye. |

| Perceived nonautonomy [33] | PNA1: The desire or need for sweet food changes with age. PNA2: The desire or need for sugar changes with age. PNA3: The desire or need for sweeteners changes with age. PNA4: Completely eliminating sugar from my diet is impossible (removed). PNA5: Completely eliminating sweet food from my diet is impossible (removed). |

| Attitude [34] | ATT1: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is a good thing for me. |

| ATT2: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is a healthy thing for me. | |

| ATT3: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is something I enjoy. | |

| ATT4: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is something I effortlessly perform. | |

| ATT5: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is a delicious thing for me. | |

| ATT6: Consuming less sugary foods/drinks is something that is valuable to me. |

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mela, D.J.; Woolner, E.M. Perspective: Total, Added, or Free? What Kind of Sugars Should We Be Talking About? Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, C.R.; Zehra, A.; Ramirez, V.; Wiers, C.E.; Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J. Impact of sugar on the body, brain, and behavior. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 2255–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.; Bell, H.; Re, R.; Nugent, A.P. Current perspectives on global sugar consumption: Definitions, recommendations, population intakes, challenges and future direction. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2023, 36, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, L.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Gaine, P.C.; Scott, M.O.; Ricciuto, L. Trends in added sugars intake and sources among U.S. adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–2018. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 897952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Sağlık Bakanlığı Halk Sağlığı Genel Müdürlüğü. Türkiye Beslenme ve Sağlık Araştırması. No. 1132; Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Sağlık Bakanlığı Halk Sağlığı Genel Müdürlüğü: Ankara, Turky, 2019; pp. 1–461. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Stanhope, K.L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016, 53, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epner, M.; Yang, P.; Wagner, R.W.; Cohen, L. Understanding the Link between Sugar and Cancer: An Examination of the Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Cancers 2022, 14, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruque, S.; Tong, J.; Lacmanovic, V.; Agbonghae, C.; Minaya, D.M.; Czaja, K. The Dose Makes the Poison: Sugar and Obesity in the United States—A Review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, L.L.C.; Nascimento, G.G.; Leite, F.R.M.; Alves-Costa, S.; Thomaz, E.B.A.F.; Alves, C.M.C.; Cury, J.A.; Ribeiro, C.C.C. Sugar intake above international recommendations and oral disease burden: A population-based study. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association. How Much Sugar Is Too Much? Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/how-much-sugar-is-too-much# (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. Policy Statement and Recommended Actions for Lowering Sugar Intake and Reducing Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Available online: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2016_en_18687.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Palmedo, P.C.; Gordon, L.M. How to be SSB-free: Assessing the attitudes and readiness for a sugar sweetened beverage-free healthcare center in the Bronx, NY. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.; Mars, M.; James, J.; de Graaf, K.; Appleton, K.M. Sweet Talk: A Qualitative Study Exploring Attitudes towards Sugar, Sweeteners and Sweet-Tasting Foods in the United Kingdom. Foods 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, M.; Bleakley, A.; Piotrowski, J.T.; Mallya, G.; Jordan, A. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption by Adult Caregivers and Their Children: The Role of Drink Features and Advertising Exposure. Public Health Educ. 2015, 42, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.S.; Mars, M.; James, J.; Appleton, K.M. Associations between attitudes towards and reported intakes of sugars, low/no-calorie sweeteners, and sweet-tasting foods in a UK sample. Appetite 2024, 194, 107169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, D.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting sugar intake using an extended theory of planned behavior in a sample of adolescents: The role of habit and self-control. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Trost, N.; Keech, J.J.; Chan DK, C.; Hamilton, K. Predicting sugar consumption: Application of an integrated dual-process, dual-phase model. Appetite 2017, 116, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, D.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting limiting ‘free sugar’ consumption using an integrated model of health behavior. Appetite 2020, 150, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.J.; Charlesworth, J.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. A Dual-Process Model Applied to Two Health-Promoting Nutrition Behaviours. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachan RR, C.; Conner, M.; Taylor, N.J.; Lawton, R.J. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gase, L.N.; Robles, B.; Barragan, N.C.; Kuo, T. Relationship Between Nutritional Knowledge and the Amount of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Consumed in Los Angeles County. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Wong, M.C.; Zhang, R.; Hamilton, K.; Hagger, M.S. Adolescent sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: An extended Health Action Process Approach. Appetite 2019, 141, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, V.E.; Savla, J.; Comber, D.L.; Flack, K.D.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Nsiah-Kumi, P.A.; Ortmeier, S.; Davy, B.M. Development of a brief questionnaire to assess habitual beverage intake (BEVQ-15): Sugar-sweetened beverages and total beverage energy intake. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. RA Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. The habitual consumer. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; He, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, Q. Mechanism of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence the green development behavior of construction enterprises. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puteri, H.E.; Arinda, N.; Dewi, S.; Sari, G. Self-control and consumptive behavior control in purchasing internet services for social networking among Muslim millennials. Eur. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertenbroch, K.; Schrift, R.Y.; Alba, J.W.; Barasch, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Giesler, M.; Knobe, J.; Lehmann, D.R.; Matz, S.; Nave, G.; et al. Autonomy in consumer choice. Mark. Lett. 2020, 31, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, W.R.; Kumar, A. Attitude organization and the attitude–behavior relation: A critique of Bagozzi and Burnkrant’s reanalysis of Fishbein and Ajzen. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Davy, B.M.; Chen, Y.C.; You, W. Exploring the theory of planned behavior to explain sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, H.; Solomon-Moore, E. A Qualitative Study to Understand the Potential Efficacy of an Information-Based Sugar Reduction Intervention among Low Socioeconomic Individuals in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Avila, A.G.; Papadaki, A.; Jago, R. The role of the home environment in sugar-sweetened beverage intake among northern Mexican adolescents: A qualitative study. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.A.; Bolger, N.; Laurenceau, J.P.; Patrick, H.; Oh, A.Y.; Nebeling, L.C.; Hennessy, E. Autonomous motivation and fruit/vegetable intake in parent–adolescent dyads. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.L.; Madden, C.; Gray, A.; Horwath, C. Self-determined, autonomous regulation of eating behavior is related to lower body mass index in a nationwide survey of middle-aged women. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Trott, S.; Sahadev, S.; Singh, R. Emotions and consumer behaviour: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2396–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Sørensen, M.I.; Eriksen, M.L.R. How the interplay between consumer motivations and values influences organic food identity and behavior. Food Policy 2018, 74, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomala, H.T.; Paasovaara, R.; Lehtola, K. Exploring consumers’ health meaning categories: Towards a health consumption meaning model. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Hoefkens, C.; Verbeke, W. Healthy, sustainable and plant-based eating: Perceived (mis) match and involvement-based consumer segments as targets for future policy. Food Policy 2017, 69, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.B.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Strøm, M.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Olsen, S.F. Sociodemographic characteristics and food habits of organic consumers–A Study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Thompson, F.E.; McGuire, L.C.; Pan, L.; Galuska, D.A.; Blanck, H.M. Sociodemographic and Behavioral Factors Associated with Added Sugars Intake among US Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Wakefield, M.; Braunack-Mayer, A.; Roder, D.; O’Dea, K.; Ettridge, K.; Dono, J. Who drinks sugar sweetened beverages and juice? An Australian population study of behaviour, awareness and attitudes. BMC Obes. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Jurado, F.; Soto-Reyes, N.; Dávila-Rodríguez, M.; Lorenzo-Leal, A.C.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.T.; Mani-López, E.; López-Malo, A. Plant-based milk alternatives: Types, processes, benefits, and characteristics. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 2320–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

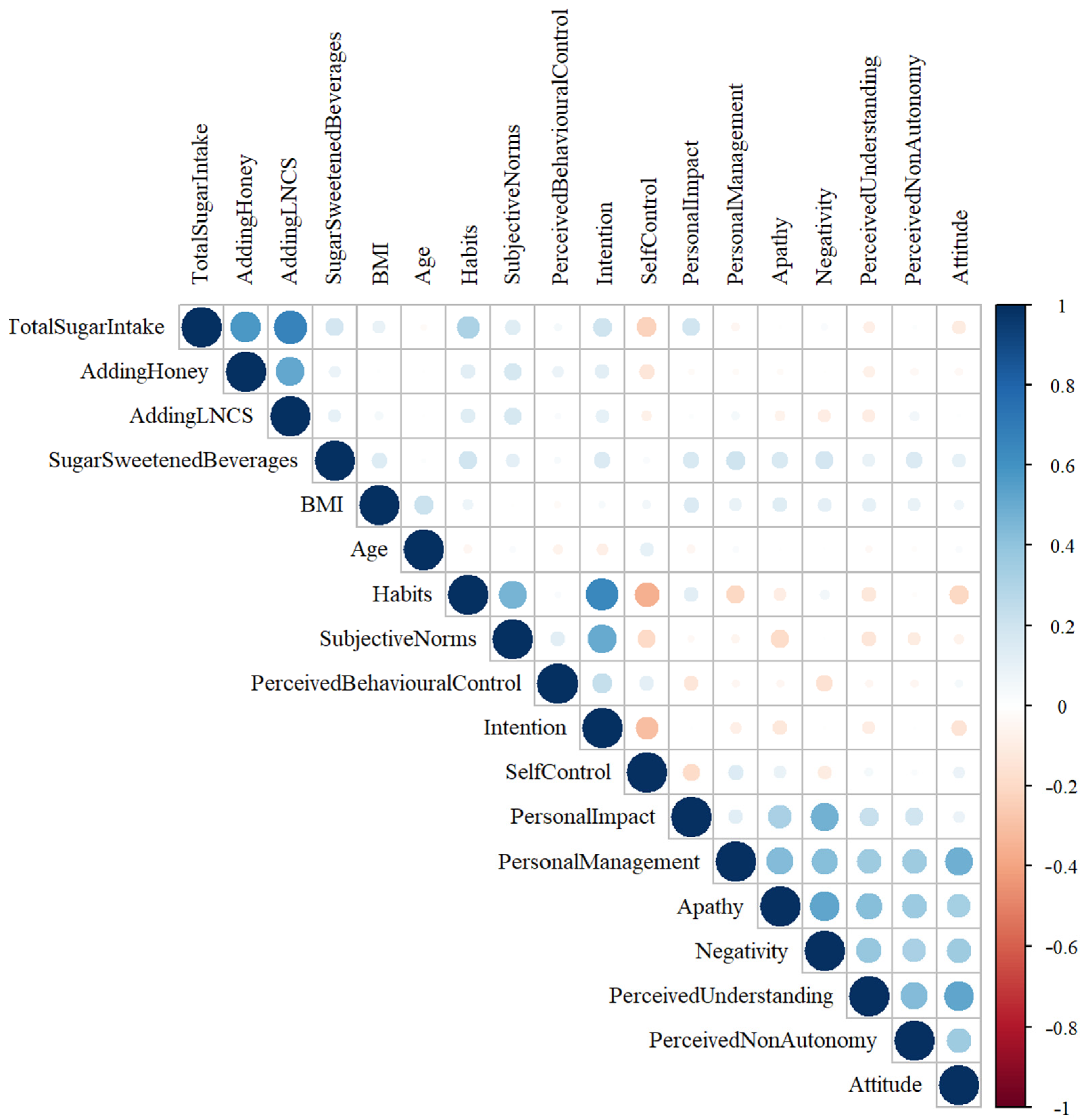

| Characteristic | x− ± SD or % (N) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Woman | 93.19 (876) |

| Man | 6.81 (64) |

| Age (years) | 34.95 ± 9.89 |

| Education level | |

| Primary/secondary school | 0.8 (7) |

| High school | 7.42 (65) |

| Associate degree | 2.28 (20) |

| Bachelor degree | 59.25 (519) |

| MSc and Ph.D. | 30.25 (265) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 42.81 (375) |

| Married | 57.19 (503) |

| Income | |

| Student and pocket money | 9.47 (83) |

| Below the minimum wage | 8.22 (72) |

| TL 17,000–27,000 | 17.92 (157) |

| TL 27,001–37,000 | 8.33 (73) |

| TL 3700–47,000 | 10.39 (91) |

| TL > 47,000 | 45.66 (400) |

| Smoking | |

| No | 74.2 (650) |

| Yes | 25.8 (226) |

| Regular alcohol intake | |

| No | 85.73 (751) |

| Yes | 14.27 (125) |

| Exercise 150 min a week | |

| No | 61.42 (538) |

| Yes | 38.58 (338) |

| Food allergy | |

| No | 83.22 (729) |

| Yes | 16.78 (147) |

| BMI | 24.82 ± 4.95 |

| Total sugar intake | 30.91 ± 12.87 |

| Adding honey | 1.42 ± 1.11 |

| Adding LNCS | 5.97 ± 3.39 |

| Sweetened beverage intake (kcal) | 98.16 ± 180.92 |

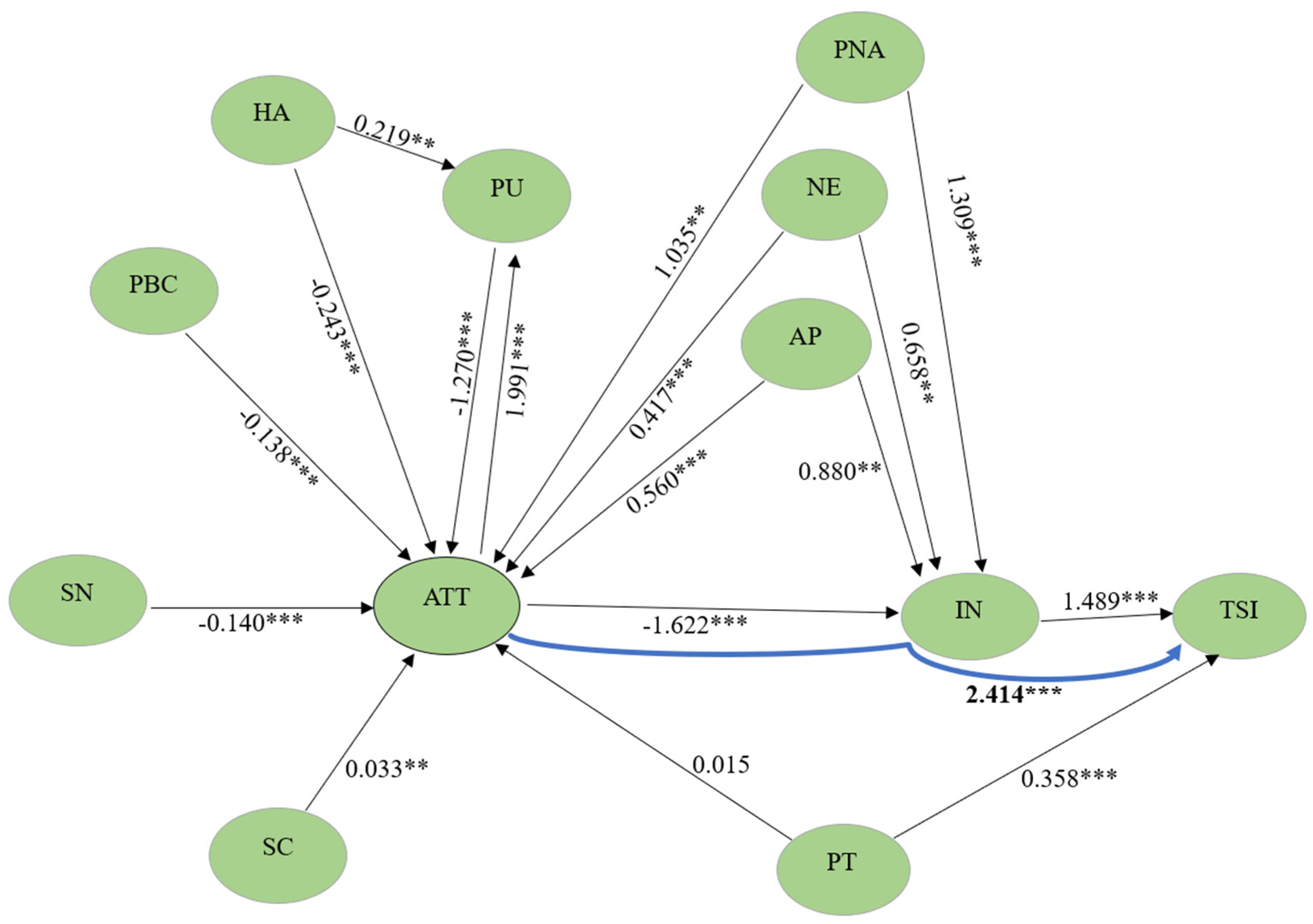

| Dependent ← Independent | β | SE | z-Value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Model | ATT ← HA | −0.243 | 0.064 | −3.780 | <0.001 *** |

| ATT ← SN | −0.140 | 0.039 | −3.551 | <0.001 *** | |

| ATT ← PBC | −0.138 | 0.035 | −3.881 | <0.001 *** | |

| ATT ← SC | 0.033 | 0.010 | 3.267 | 0.001 ** | |

| ATT ← PI | 0.015 | 0.009 | 1.663 | 0.096 | |

| ATT ← AP | 0.560 | 0.155 | 3.602 | <0.001 *** | |

| ATT ← NE | 0.417 | 0.088 | 4.739 | <0.001 *** | |

| ATT ← PU | −1.270 | 0.299 | −4.248 | <0.001 *** | |

| ATT ← PNA | 1.035 | 0.217 | 4.765 | <0.001 *** | |

| IN ← ATT | −1.622 | 0.412 | −3.935 | <0.001 *** | |

| TSI ← IN | 1.489 | 0.252 | 5.920 | <0.001 *** | |

| TSI ← ATT | −0.071 | 0.165 | −0.431 | 0.666 | |

| TSI ← IN ← ATT | −2.414 | 0.737 | −3.276 | 0.001 ** | |

| Predictive Adjustments | IN ← PU | −2.016 | 0.454 | −4.446 | <0.001 *** |

| IN ← PNA | 1.709 | 0.429 | 3.988 | <0.001 *** | |

| IN ← NE | 0.658 | 0.180 | 3.651 | <0.001 *** | |

| IN ← AP | 0.880 | 0.266 | 3.307 | 0.001 ** | |

| PU ← ATT | 1.991 | 0.147 | 13.509 | <0.001 *** | |

| PU ← HA | 0.219 | 0.076 | 2.868 | 0.004 ** | |

| TSI ← PI | 0.358 | 0.074 | 4.820 | <0.001 *** | |

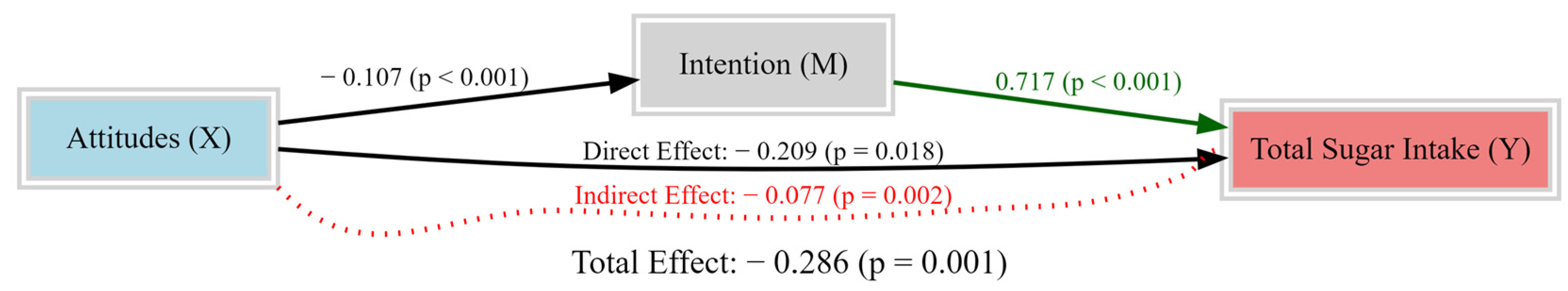

| Independent → Dependent | β | SE | t-Value | Std. β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X → M | −0.107 | 0.024 | −4.395 | −0.142 | <0.001 *** |

| M → Y | 0.717 | 0.118 | 6.102 | 0.196 | <0.001 *** |

| X(c’) →Y | −0.209 | 0.089 | −2.360 | −0.076 | 0.018 * |

| X → M → Ya | −0.077 | 0.025 | −3.080 | −0.028 | 0.002 ** |

| X → M → Y + c’ | −0.286 | 0.090 | −3.199 | −0.104 | 0.001 ** |

| Model 1 | β | SE | t | %95 Lower | %95 Upper | p | |

| (Intercept) | 29.733 | 2.298 | 12.936 | 25.228 | 34.237 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | 1.958 | 1.385 | 1.414 | −0.757 | 4.672 | 0.157 | |

| Age | −0.035 | 0.039 | −0.904 | −0.112 | 0.041 | 0.366 | |

| Education Level | 0.229 | 0.431 | 0.531 | −0.616 | 1.074 | 0.596 | |

| Marital Status | 1.118 | 0.779 | 1.435 | −0.409 | 2.645 | 0.151 | |

| Occupation | −0.148 | 0.272 | −0.544 | −0.680 | 0.385 | 0.587 | |

| Income | 0.292 | 0.199 | 1.464 | −0.099 | 0.682 | 0.143 | |

| Smoking | 0.029 | 0.779 | 0.037 | −1.497 | 1.555 | 0.970 | |

| Regular Alcohol Intake | −0.511 | 0.957 | −0.534 | −2.385 | 1.364 | 0.593 | |

| Exercise 150 min A Week | 0.229 | 0.704 | 0.326 | −1.151 | 1.610 | 0.745 | |

| Change In Dietary Habits In The Last 12 Months | −0.790 | 0.488 | −1.618 | −1.747 | 0.167 | 0.106 | |

| Health Problem | −1.011 | 0.905 | −1.117 | −2.784 | 0.762 | 0.264 | |

| Food Allergy | −2.888 | 0.934 | −3.090 | −4.719 | −1.056 | 0.002 * | |

| Currently Diet | 1.052 | 0.753 | 1.397 | −0.423 | 2.527 | 0.162 | |

| Model 2 | β | SE | Std. β | t | %95 Lower | %95 Upper | p |

| (intercept) | 0.052 | 0.036 | 1.463 | −0.018 | 0.122 | 0.144 | |

| food allergy ref: no (0) | −0.303 | 0.086 | −0.114 | −3.525 | −0.471 | −0.134 | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kural Enç, H.P.; Kahrıman, M.; Gençalp, C.; Yılmaz, S.; Köse, G.; Baş, M. Factors Driving Individuals’ Attitudes toward Sugar and Sweet-Tasting Foods: An Analysis within the Scope of Theory of Planned Behavior. Foods 2024, 13, 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193109

Kural Enç HP, Kahrıman M, Gençalp C, Yılmaz S, Köse G, Baş M. Factors Driving Individuals’ Attitudes toward Sugar and Sweet-Tasting Foods: An Analysis within the Scope of Theory of Planned Behavior. Foods. 2024; 13(19):3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193109

Chicago/Turabian StyleKural Enç, Hatice Pınar, Meryem Kahrıman, Cansu Gençalp, Salim Yılmaz, Gizem Köse, and Murat Baş. 2024. "Factors Driving Individuals’ Attitudes toward Sugar and Sweet-Tasting Foods: An Analysis within the Scope of Theory of Planned Behavior" Foods 13, no. 19: 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193109

APA StyleKural Enç, H. P., Kahrıman, M., Gençalp, C., Yılmaz, S., Köse, G., & Baş, M. (2024). Factors Driving Individuals’ Attitudes toward Sugar and Sweet-Tasting Foods: An Analysis within the Scope of Theory of Planned Behavior. Foods, 13(19), 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193109