Effects of Daily Ingestion of Two SunGold Kiwifruit for 6 Weeks on Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Exploratory Intervention Study

Abstract

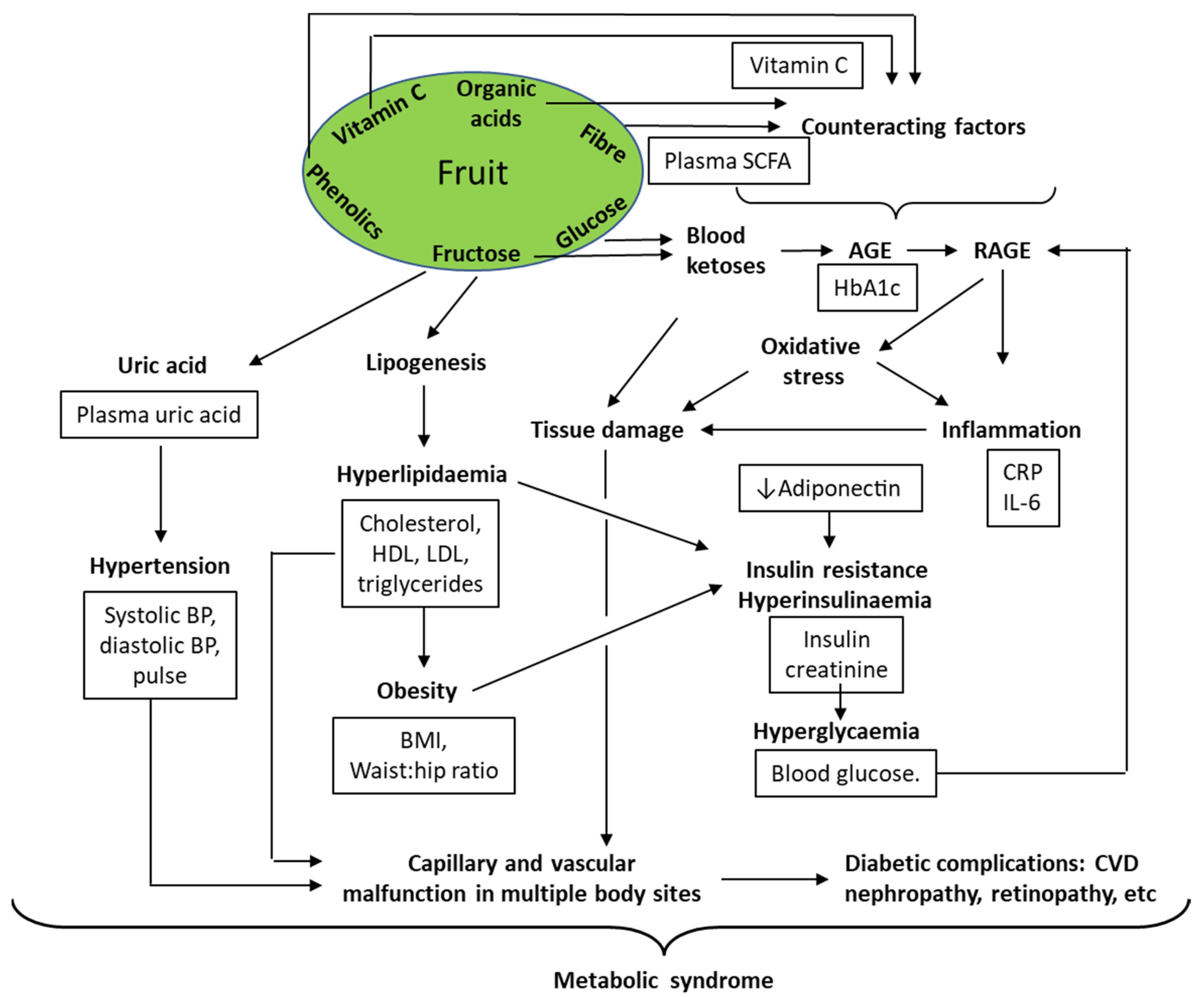

:1. Introduction

- Creating insulin demand leading to B-cell exhaustion [12].

- Reacting chemically and non-specifically with various body components to form advanced glycation end (AGE) products, which react with AGE receptors (RAGE) that induce inflammatory responses [4].

- Overloading the mitochondrial respiratory system, leading to formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and creating a state of oxidative stress, which is a further inflammatory stimulus [13].

- Increasing uric acid production as a by-product of fructose catabolism, with possible elevation of blood pressure and other biomarkers of metabolic syndrome [16].

- Components that slow the absorption of sugars so that sugar disposal processes for removal of fructose and glucose from the blood can match blood sugar loading, preventing high and/or prolonged blood sugar concentrations. Cell wall remnants (dietary fibre), organic acids, and phenolic compounds may all slow glucose absorption from the gut [17].

- Antioxidant phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds from fruit, may augment intrinsic antioxidant systems such as those based on reduced glutathione (GSH) [18].

- Cell wall remnants that are fermented in the hind gut to microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which may have multiple effects on biochemical systems mediating the systemic damage that emerges from long-term hyperglycaemia [19].

2. Materials and Methods

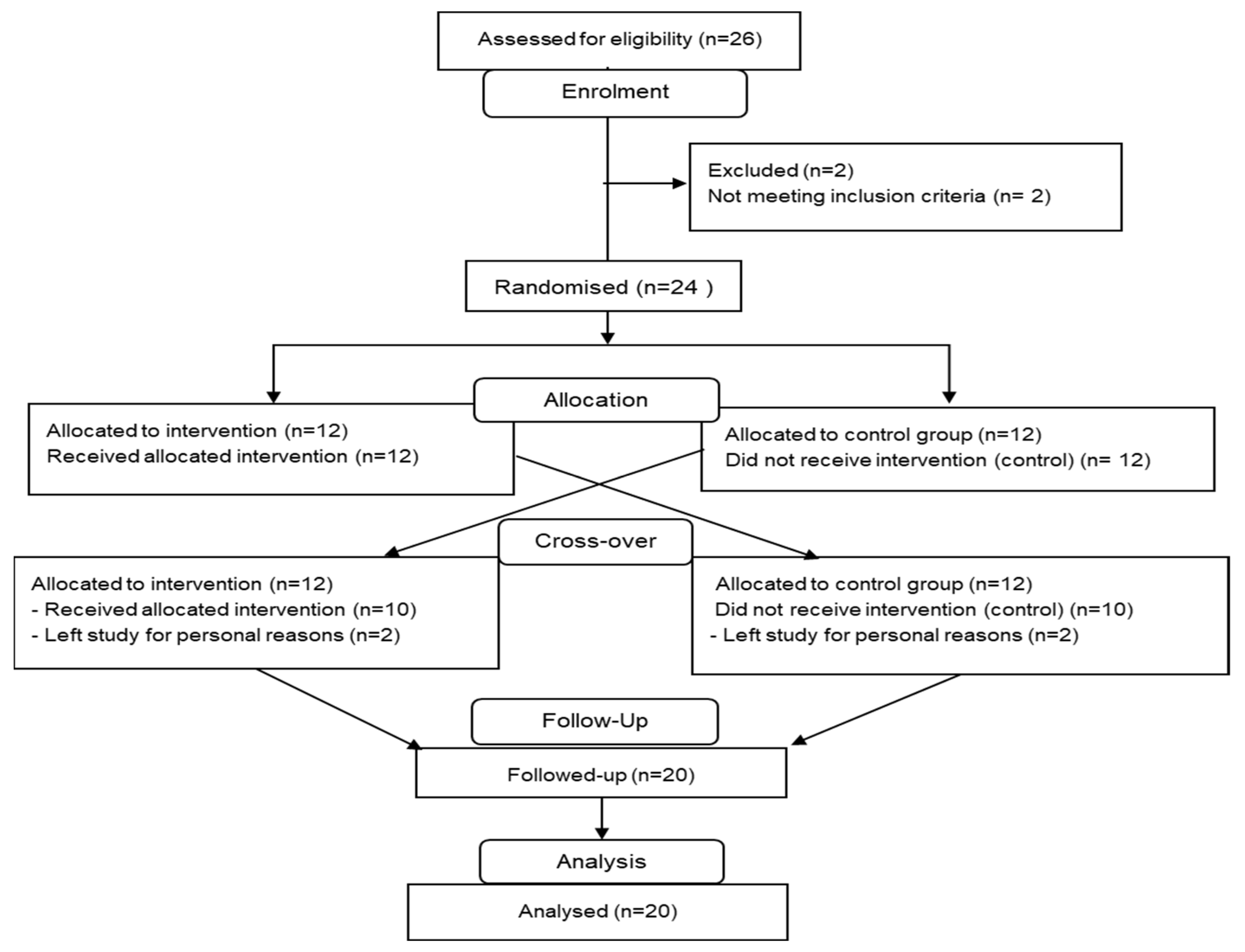

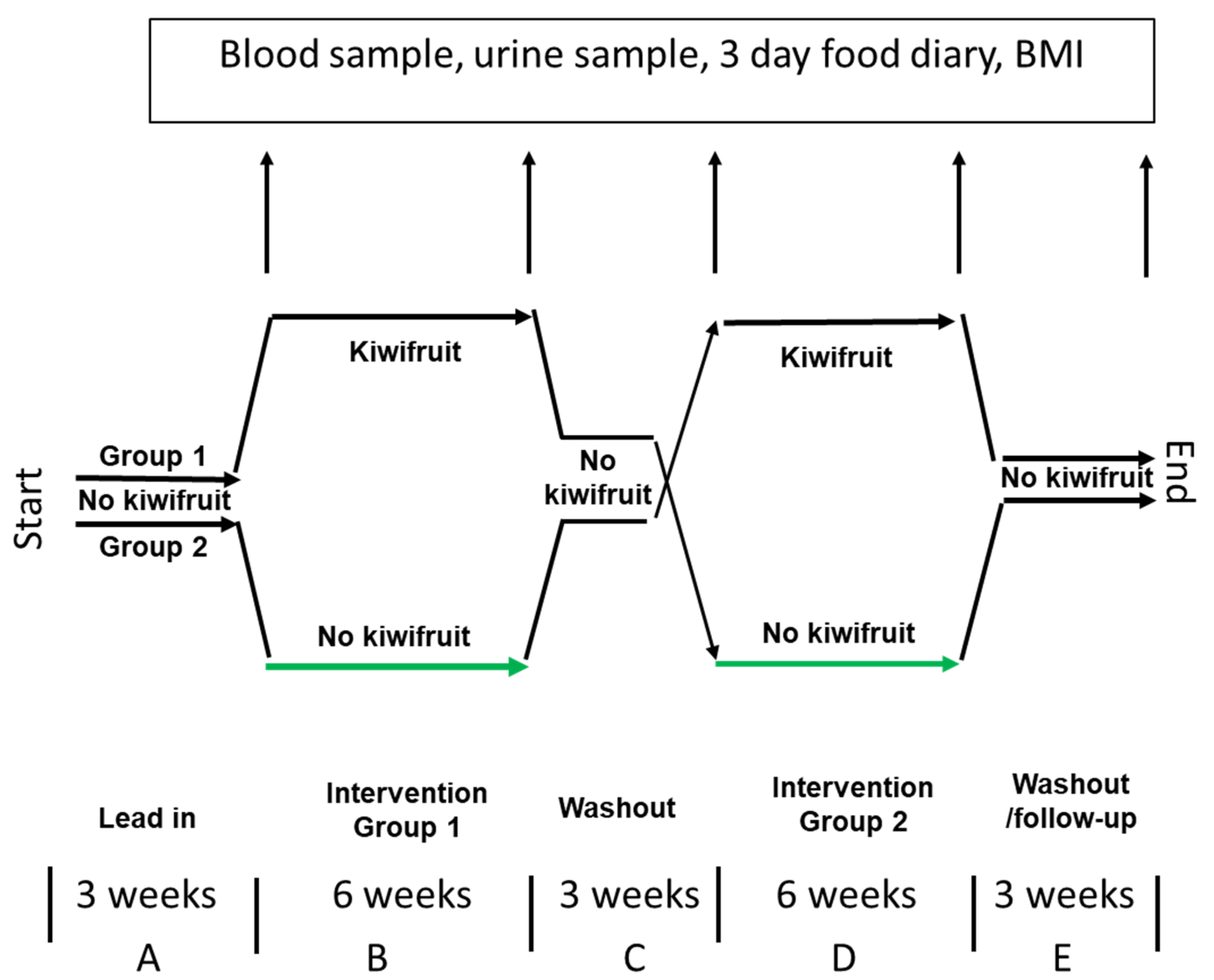

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Participant Number (n)

2.3. Participants

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Participant Instructions

2.7. Blood and Urine Sampling

2.8. Analyses

2.8.1. Plasma Ascorbic Acid Analysis

2.8.2. Urine Ascorbic Acid Analysis

2.8.3. Dietary Fibre and Ascorbic Acid Intakes

2.8.4. Anthropometric Changes

2.8.5. Cardiovascular Variables

2.8.6. Metabolic Biomarkers

2.8.7. Hormones and Peptides

2.8.8. Plasma Lipids

2.8.9. Plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acids

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

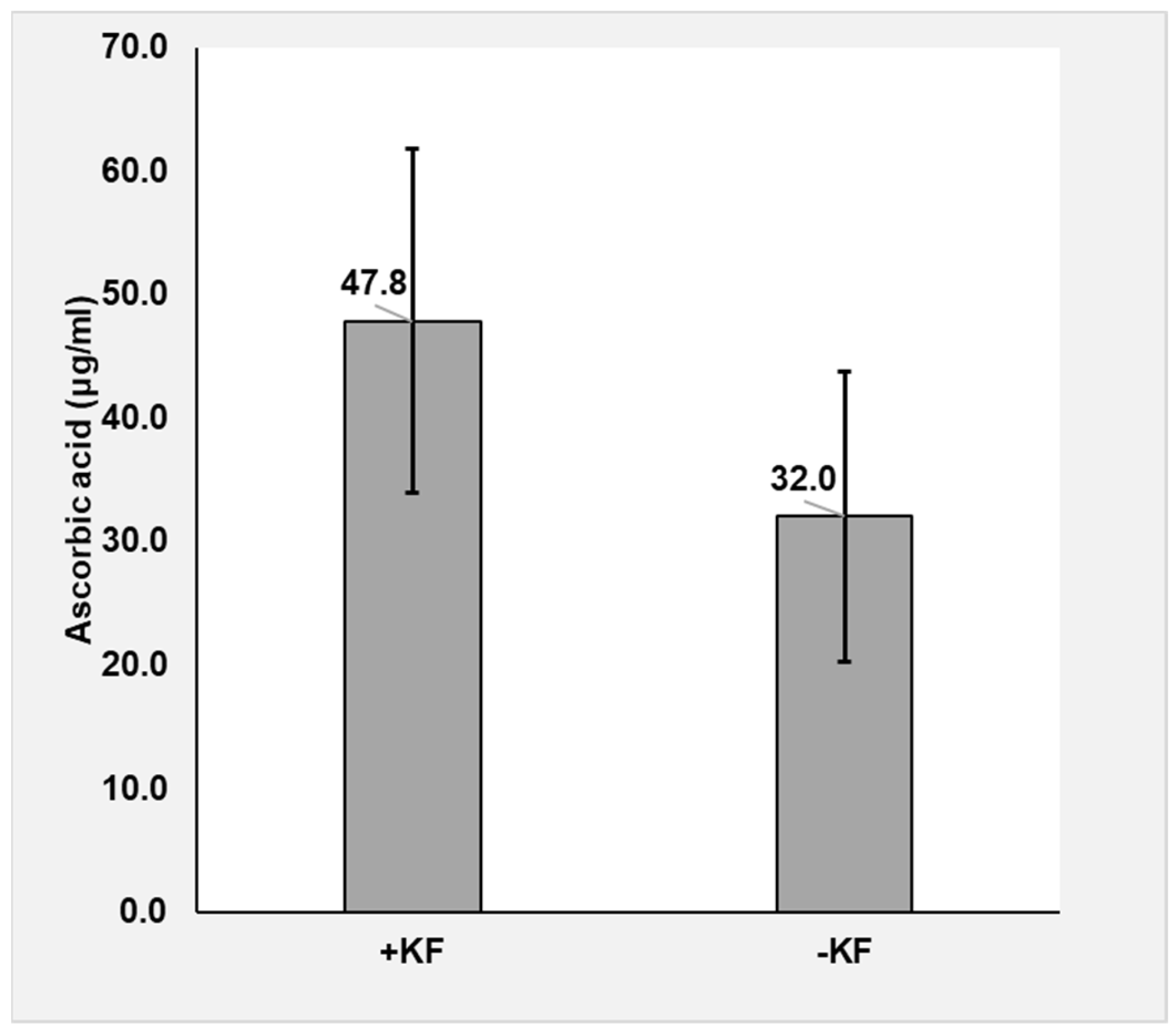

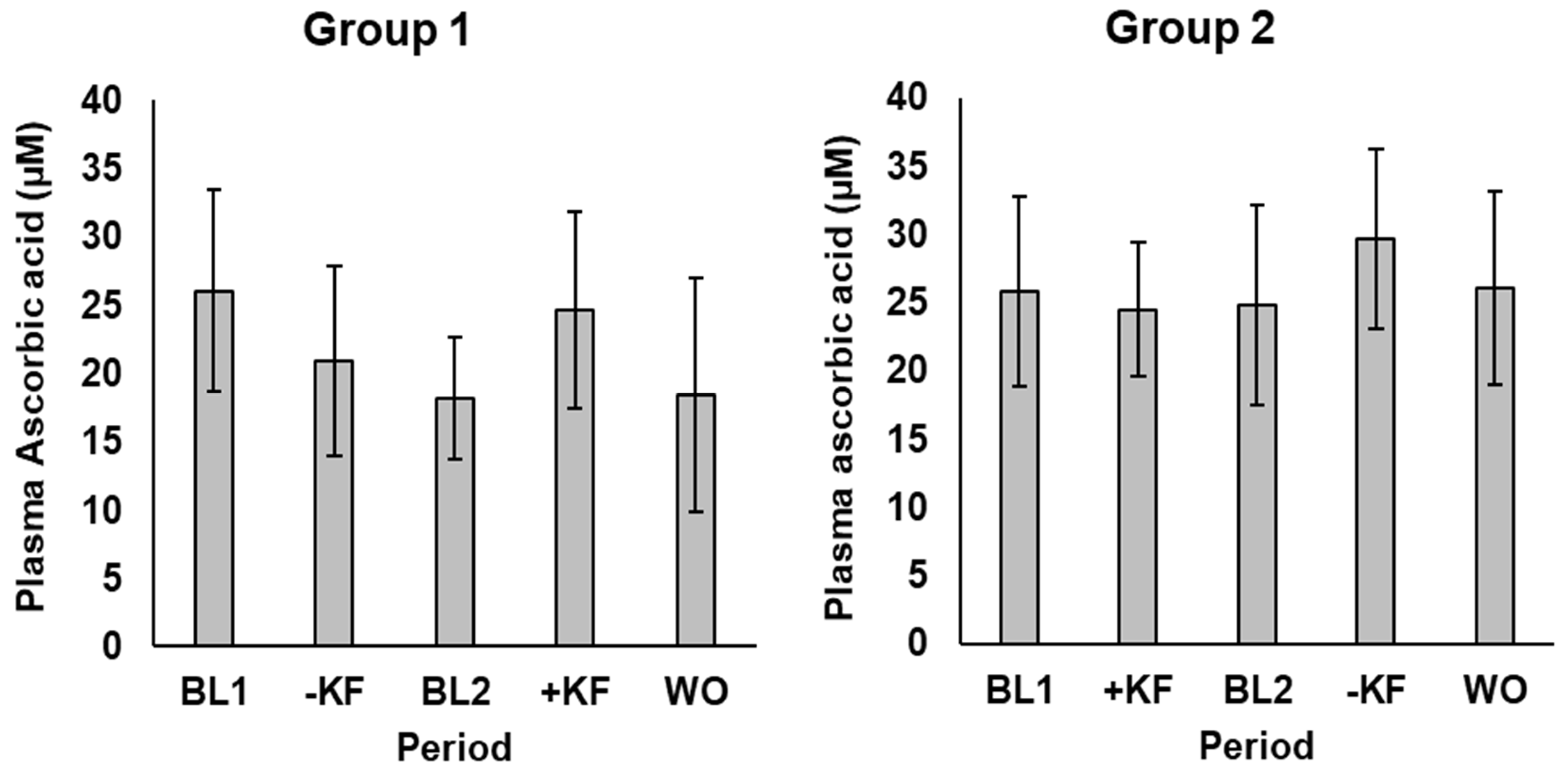

3.1.1. Ascorbic Acid

3.1.2. Anthropometric Measures

3.1.3. Cardiovascular Variables

3.1.4. Metabolic Biomarkers

3.1.5. Hormones and Peptides

3.1.6. Plasma Lipids

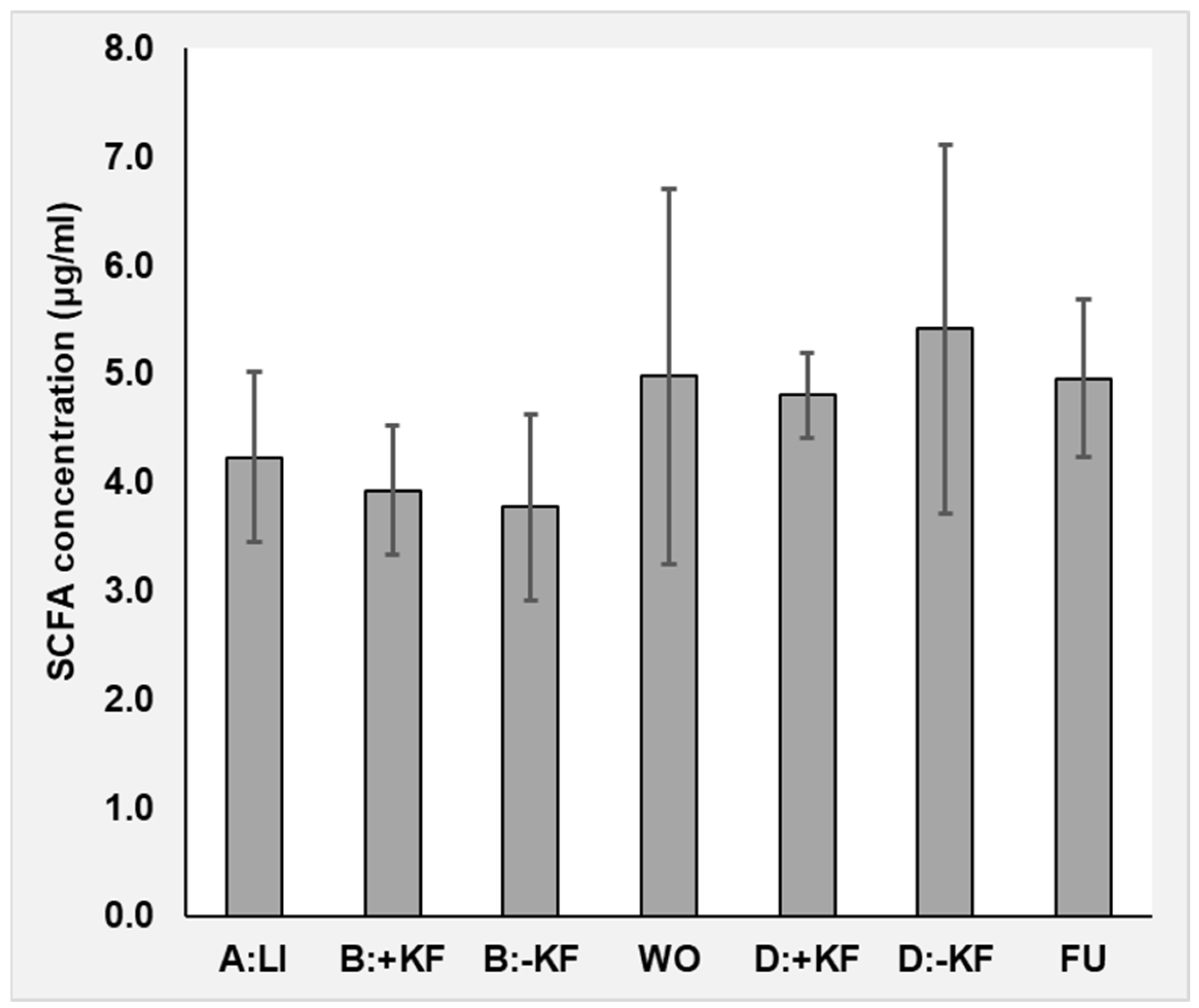

3.1.7. Dietary Fibre and Plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acids

4. Discussion

4.1. Ascorbic Acid

4.2. Metabolic/Cardiovascular Variables

4.3. Short-Chain Fatty Acids

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Biomarker | Relationship to Health Endpoint |

|---|---|

| Anthropometric | |

| BMI kg/m2 | A measure of overweight and obesity associated with many non-communicable diseases [34]. |

| Waist:hip ratio | Alternative measure of obesity. Central obesity is a component of metabolic syndrome and predictive of many health outcomes [35]. |

| Circulatory | |

| Systolic BP mmHg | Risk factor for cardiovascular disease and many other circulation-related disorders [36]. |

| Diastolic BP mmHg | An independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease [37,38]. |

| Pulse bpm | Positively related to cardiovascular and associated diseases and to all-cause mortality [39]. |

| Metabolic | |

| Blood glucose mmol/L | High blood glucose concentrations increase risk of numerous diseases typical of diabetic complications, by several mechanisms [13]. |

| HbA1c mmol/mol | An indicator of the extent of glycation over an extended period and elevated risk of numerous diabetic complications resulting from high blood glucose [40,41,42]. |

| Insulin uU/mL | High insulin is a risk factor for a large number of medical disorders [43]. |

| Uric acid mmol/L | Fructose metabolism elevates uric acid, which may promote metabolic syndrome [16]. |

| Creatinine µmol/L | Metabolite with diverse effects including improved glucose tolerance [44]. A marker of kidney function and diabetic nephropathy. |

| Adiponectin mg/mL | Leads to improved glucose tolerance and lipid metabolism [45]. |

| Inflammatory | |

| CRP mg/mL | Widely used indicator of inflammation induced by IL-6 and predicting diabetic complications [46] and cardiovascular disease [47]. |

| IL-6 pg/mL | Inflammatory cytokine induced by hyperglycaemia and implicated in insulin resistance and ongoing progression to diabetes and its complications [46,48]. |

| Lipidaemic | |

| Cholesterol mmol/L LDL Chol mmol/L HDL Chol mmol/L Triglycerides mmol/L | Dyslipidaemia combines with hyperglycaemia, hypertension, and duration in emergence of pathophysiology underlying diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease [49]. Diabetic dyslipidaemia is characterised by elevated fasting and postprandial triglycerides, low HDL-cholesterol, and elevated LDL-cholesterol particles, which represent the major link between diabetes and the increased cardiovascular risk of diabetic patients [50]. |

| Average | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.67–1.87 |

| Weight (kg) | 83.8 | 13.7 | 66–131 |

| BMI | 26.2 | 3.3 | 20.9–37.5 |

| Systolic BP | 131.2 | 13.4 | 100–161 |

| Diastolic BP | 84.2 | 8.9 | 70–98 |

| Pulse | 63.0 | 10.4 | 45–87 |

| HbA1c | 29.3 | 3.3 | 23–36 |

| Glucose | 4.42 | 0.39 | 3.65–5.15 |

| Ethnicity: | Trial start | Trial finish | |

| Caucasian | 17 | 15 | |

| Chinese | 2 | 1 | |

| Vietnamese | 2 | 1 | |

| Indian | 3 | 3 |

| Control Start | Control End | Kiwifruit Start | Kiwifruit End | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 22) | (n = 21) | (n = 22) | (n = 21) | |||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Anthropometric | ||||||||

| BMI kg/m2 | 26.6 | 3.10 | 26.6 | 3.16 | 26.7 | 3.05 | 26.7 | 3.21 |

| Waist:hips ratio | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Circulatory | ||||||||

| Systolic BP mmHg | 128 | 10.8 | 128 | 9.62 | 130 | 8.44 | 133 | 8.25 |

| Diastolic BP mmHg | 81.9 | 8.91 | 82.2 | 8.25 | 83.2 | 7.97 | 83.5 | 7.79 |

| Pulse bpm | 61.4 | 9.38 | 59.4 | 10.5 | 62.3 | 9.38 | 57.8 | 9.17 |

| Metabolic | ||||||||

| HbA1c mmol/mol | 30.8 | 3.00 | 32.1 | 3.35 | 31.1 | 3.99 | 31.5 | 3.25 |

| Blood glucose mmol/L | 4.19 | 0.35 | 4.18 | 0.39 | 4.29 | 0.43 | 4.26 | 0.43 |

| Insulin uU/mL | 5.23 | 3.47 | 6.03 | 2.84 | 5.29 | 2.49 | 5.33 | 2.57 |

| Creatinine µmol/L | 91.6 | 13.1 | 90.3 | 13.3 | 92.2 | 12.2 | 88.6 | 13.3 |

| Inflammatory | ||||||||

| Adiponectin mg/mL | 6.31 | 3.42 | 6.57 | 3.02 | 6.81 | 5.07 | 6.38 | 2.61 |

| Uric acid mmol/L | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| CRP mg/mL | 0.77 | 1.13 | 3.15 | 8.57 | 0.61 | 0.94 | 1.57 | 4.08 |

| IL 6 pg/mL | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 1.05 |

| Lipidaemic | ||||||||

| Cholesterol mmol/L | 4.87 | 1.17 | 5.05 | 0.96 | 4.89 | 1.13 | 5.01 | 1.19 |

| HDL Chol mmol/L | 1.65 | 0.35 | 1.67 | 0.33 | 1.66 | 0.39 | 1.66 | 0.33 |

| LDL Chol mmol/L | 2.65 | 0.98 | 2.79 | 0.87 | 2.64 | 0.94 | 2.79 | 0.96 |

| Triglycerides mmol/L | 1.29 | 0.80 | 1.3 | 0.60 | 1.31 | 0.70 | 1.24 | 0.69 |

References

- Wang, D.D.; Li, Y.P.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rosner, B.A.; Sun, Q.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; et al. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mortality Results from 2 Prospective Cohort Studies of US Men and Women and a Meta-Analysis of 26 Cohort Studies. Circulation 2021, 143, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.P.; Ansell, J.; Drummond, L.N. The nutritional and health attributes of kiwifruit: A review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2659–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengstie, M.A.; Abebe, E.C.; Teklemariam, A.B.; Mulu, A.T.; Agidew, M.M.; Azezew, M.T.; Zewde, E.A.; Teshome, A.A. Endogenous advanced glycation end products in the pathogenesis of chronic diabetic complications. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1002710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugliucci, A. Formation of Fructose-Mediated Advanced Glycation End Products and Their Roles in Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ-Br. Med. J. 2014, 349, g4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, K.L.; Medici, V.; Bremer, A.A.; Lee, V.; Lam, H.D.; Nunez, M.V.; Chen, G.X.; Keim, N.L.; Havel, P.J. A dose-response study of consuming high-fructose corn syrup-sweetened beverages on lipid/lipoprotein risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, M.R. Normal Roles for Dietary Fructose in Carbohydrate Metabolism. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3117–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

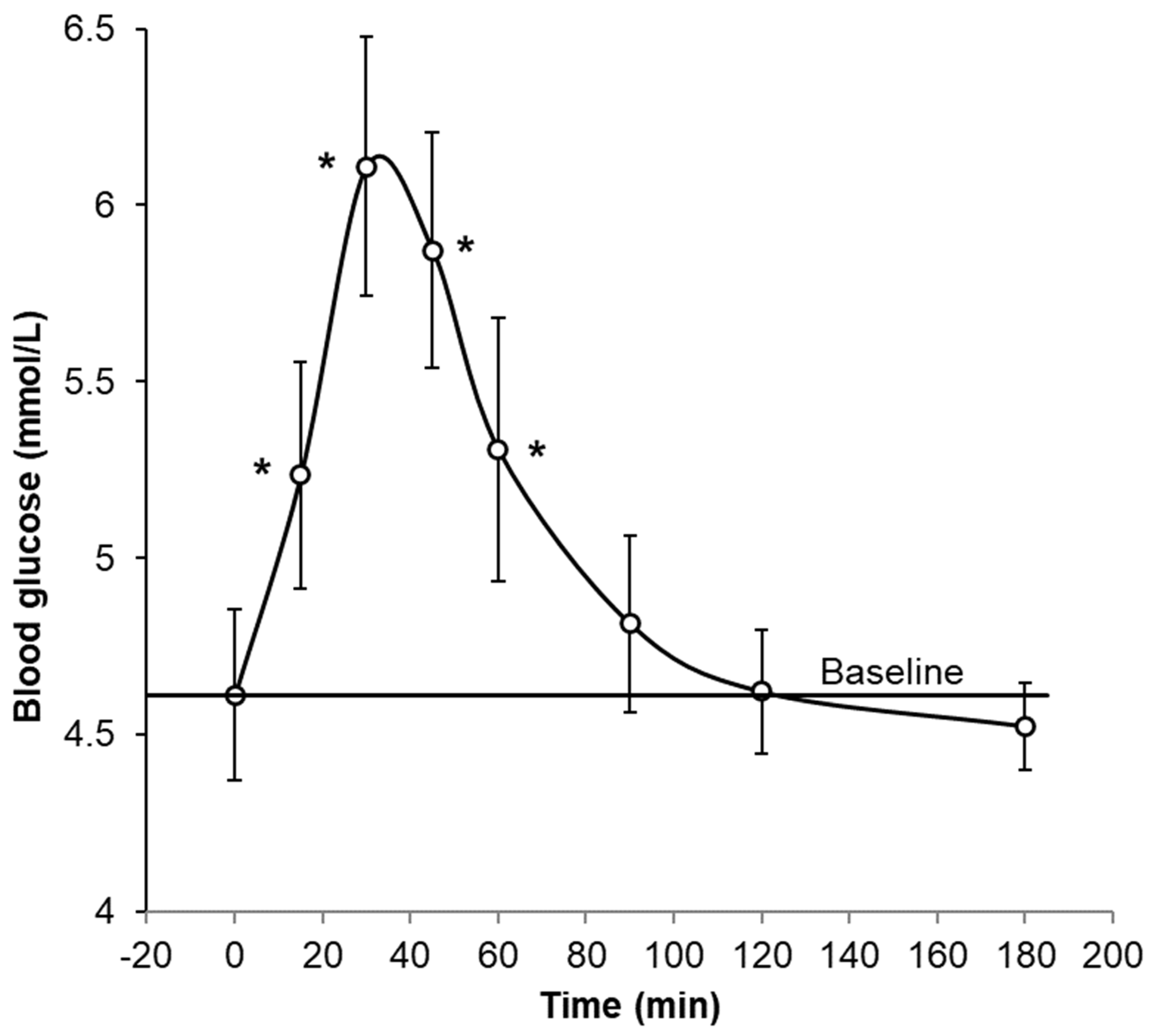

- Mishra, S.; McLaughlin, A.; Monro, J. Food Order and Timing Effects on Glycaemic and Satiety Responses to Partial Fruit-for-Cereal Carbohydrate Exchange: A Randomized Cross-Over Human Intervention Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, R.C.O.; Vieira, A.F.; Moritz, C.E.J.; Reischak-Oliveira, A. Effects of fructose consumption on postprandial TAG: An update on systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieronimus, B.; Medici, V.; Bremer, A.A.; Lee, V.; Nunez, M.V.; Sigala, D.M.; Keim, N.L.; Havel, P.J.; Stanhope, K.L. Synergistic effects of fructose and glucose on lipoprotein risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adults. Metab.-Clin. Exp. 2020, 112, 154356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, N.; Lin, L.; Contreras, C.J.; Templin, A.T. beta-Cell Death in Diabetes: Past Discoveries, Present Understanding, and Potential Future Advances. Metabolites 2021, 11, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsley, R.N.; Moreau, F.; Gupta, M.K.; Radulescu, A.; DeBosch, B.; Softic, S. Tissue-Specific Fructose Metabolism in Obesity and Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2020, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, K.L.; Schwarz, J.M.; Keim, N.L.; Griffen, S.C.; Bremer, A.A.; Graham, J.L.; Hatcher, B.; Cox, C.L.; Dyachenko, A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Leoncini, G.; Esposito, P.; Garibotto, G.; Pontremoli, R.; Viazzi, F. Fructose and Uric Acid: Major Mediators of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Starting at Pediatric Age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monro, J.; Mishra, S.; Stoklosinski, H.; Bentley-Hewitt, K.; Hedderley, D.; Dinnan, H.; Martell, S. Dietary Fibre and Organic Acids in Kiwifruit Suppress Glycaemic Response Equally by Delaying Absorption-A Randomised Crossover Human Trial with Parallel Analysis of C-13-Acetate Uptake. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jideani, A.I.O.; Silungwe, H.; Takalani, T.; Omolola, A.O.; Udeh, H.O.; Anyasi, T.A. Antioxidant-rich natural fruit and vegetable products and human health. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamone, D.; Rivellese, A.A.; Vetrani, C. The relationship between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The possible role of dietary fibre. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N. Ascorbic acid metabolism and functions: A comparison of plants and mammals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, J.; Lubransky, A.; Mishra, S.; Haszard, J.; Venn, B. Metabolic and Blood Pressure Effects of Consuming Two Kiwifruit Daily for 7 Weeks: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Bentley-Hewitt, K.; Lubransky, A.; Venn, B.; Hedderley, D.; Dinnan, H.; Martell, S.; Haszard, J.; Monro, J. Metabolic, anthropometric and blood pressure effects of adding two kiwifruit or bottled water into the diets of people with pre-diabetes: A randomised, parallel group, intervention study. Recent Prog. Nutr. 2022, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, J.A.; Mishra, S. Digestion-resistant remnants of vegetable vascular and parenchyma tissues differ in their effects in the large bowel of rats. Food Dig. 2010, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.M.; Zhang, G.B.; Qian, S.S.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, M.M. Associations between dietary fiber intake and cardiovascular risk factors: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 972399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natto, Z.S.; Yaghmoor, W.; Alshaeri, H.K.; Van Dyke, T.E. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Effects on Inflammatory Biomarkers and Lipid Profiles among Diabetic and Cardiovascular Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.; Keogh, J.B.; Pedersen, E.; Clifton, P.M. Fructose acute effects on glucose, insulin, and triglyceride after a solid meal compared with sucralose and sucrose in a randomized crossover study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, N.M.; Delepee, R.; Maume, D.; Le Bizec, B.; Nguyen, P.G.; Champ, M.M.; Martin, L.J.; Dumon, H.J. Rapid measurement of C-13-enrichment of acetic, propionic and butyric acids in plasma with solid phase microextraction coupled to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 512, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Horst, K.W.; Serlie, M.J. Fructose Consumption, Lipogenesis, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, M.S. Pitfalls in Hemoglobin A1c Measurement: When Results may be Misleading. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.L.; Stifft, J.; Gross, J.L. The effect of aspirin and vitamins C and E on HbA1c assays. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 372, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, I.M.; Monro, J.A. Fiber: Composition, structures, and functional properties. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2013, 68, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, A.; Ma, R.C.W.; Snehalatha, C. Diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2010, 375, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Strandberg, T.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Frank, P.; Jokela, M.; Ervasti, J.; Suominen, S.B.; Vahtera, J.; Sipila, P.N.; et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: An observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.B. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 316, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Perel, P.; Mensah, G.A.; Ezzati, M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, I. Systolic and diastolic hypertension independently predict CVD risk. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.C.; Conell, C.; Ren, X.S.; Banki, N.M.; Chan, S.L.; Rao, V.A.; Melles, R.B.; Bhatt, D.L. Effect of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure on Cardiovascular Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Sen, A.; o’Hartaigh, B.; Janszky, I.; Romundstad, P.R.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J. Resting heart rate and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and all-cause mortality—A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Liu, T.; Zhou, J.D.; Zhang, Q.P.; Wong, W.T.; Tse, G. Predictions of diabetes complications and mortality using hba1c variability: A 10-year observational cohort study. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrha, J.; Soupal, J.; Skrha, J.; Prazny, M. Glucose variability, HbA1c and microvascular complications. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016, 17, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Ishibashi, F. Impact of normalised HbA1c on diabetic neuropathy and other microvascular complications in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Rohling, M.; Martin, S. Insulin: Too much of a good thing is bad. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R. Creatine in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H.; Yoshida, H. Beneficial Effects of Adiponectin on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerotic Progression: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, J.; Radovanovic, J.; Banjac, K.; Obradovic, M.; Essack, M.; Zafirovic, S.; Gluvic, Z.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of C-Reactive Protein in Diabetic Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 3706508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Bradwin, G.; Hasan, A.A.; Rifai, N. Comparison of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as biomarkers of residual risk in contemporary practice: Secondary analyses from the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2952–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, F.F.; Kraaijenhof, J.M.; von Herrath, M.; Hovingh, G.K.K.; von Scholten, B.J. Interleukin 6 in diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, S.; Sas, K.M.; Abcouwer, S.F.; Feldman, E.L.; Gardner, T.W.; Pennathur, S.; Fort, P.E. New insights into the mechanisms of diabetic complications: Role of lipids and lipid metabolism. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y.; Parhofer, K.G. Diabetic dyslipidemia. Metab.-Clin. Exp. 2014, 63, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between Start and Finish within Treatments | Values at Finish with Start as Covariate | |||||||||

| Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p | Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p | |

| Vit C intake mg/day (n = 20) | 3 | 156 | 59 | 30.2 | <0.001 | 107 | 257 | 46 | 47.7 | <0.001 |

| Square root of urinary Vit C µg/mL (n = 22) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.328 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 5.3 | 0.033 |

| (B) | ||||||||||

| Control Start No Kiwifruit | Control End No Kiwifruit | Kiwifruit Start | Kiwifruit End | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Vit C intake mg/day (n = 20) | 109 | 67 | 107 | 94 | 109 | 85 | 257 | 98 | ||

| Urinary Vit C µg/mL (n = 22) | 14 | 38 | 31 | 66 | 14 | 23 | 46 | 61 | ||

| Within-Treatment Difference between Start and Finish of 6 Week Intervention | Values at Finish with Start as Covariate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p | Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p |

| Anthropometric | ||||||||||

| BMI kg/m2 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.28 | 0.0 | 0.947 | 26.6 | 26.7 | 0.18 | 1.1 | 0.302 |

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.0093 | 0.006 | 0.0203 | 0.1 | 0.739 | 0.9722 | 0.9725 | 0.0134 | 0.0 | 0.965 |

| Circulatory | ||||||||||

| Systolic BP mmHg | −0.4 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 0.103 | 127.7 | 132.0 | 2.6 | 12.5 | 0.003 |

| Diastolic BP mmHg | −0.9 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 0.527 | 81.5 | 83.3 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 0.096 |

| Pulse bpm | −2.6 | −4.1 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 0.374 | 59.0 | 58.4 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.626 |

| Metabolic | ||||||||||

| HbA1c mmol/mol | 1.15 | 0.31 | 1.34 | 1.7 | 0.206 | 32.05 | 31.26 | 0.91 | 3.4 | 0.084 |

| Bloodglucose mmol/L | 0.033 | −0.080 | 0.186 | 1.7 | 0.216 | 4.258 | 4.164 | 0.209 | 0.9 | 0.356 |

| Insulin µ/mL | 0.63 | −0.04 | 1.46 | 0.9 | 0.352 | 5.96 | 5.21 | 0.95 | 2.8 | 0.113 |

| Uric acid mmol/L | −0.013 | −0.015 | 0.022 | 0.0 | 0.843 | 0.347 | 0.345 | 0.014 | 0.1 | 0.756 |

| Creatinine µmol/L | −1.0 | −3.4 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 0.145 | 90.3 | 88.6 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.140 |

| Inflammatory | ||||||||||

| Adiponectin mg/mL | 0.15 | −0.25 | 1.92 | 0.2 | 0.664 | 6.52 | 6.54 | 0.68 | 0.0 | 0.961 |

| CRP mg/mL | 2.21 | 0.77 | 4.27 | 0.5 | 0.486 | 2.90 | 1.40 | 4.35 | 0.5 | 0.491 |

| IL-6 pg/mL | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.2 | 0.644 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 0.34 | 1.1 | 0.315 |

| Lipidaemic | ||||||||||

| Cholesterol mmol/L | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.0 | 0.893 | 5.01 | 4.99 | 0.36 | 0.0 | 0.893 |

| LDL Chol mmol/L | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.3 | 0.618 | 2.75 | 2.79 | 0.22 | 0.2 | 0.677 |

| HDL Chol mmol/L | 0.026 | −0.012 | 0.143 | 0.3 | 0.586 | 1.686 | 1.649 | 0.148 | 0.3 | 0.599 |

| Triglycerides mmol/L | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.0 | 0.851 | 1.26 | 1.25 | 0.14 | 0.0 | 0.930 |

| (A) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between Start and Finish within Treatments | Values at Finish with Start as Covariate | |||||||||

| Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p | Control | Kiwi | l.s.d. | F | p | |

| Dietary fibre intake g/day (n = 20) | −3 | 3 | 7 | 3.4 | 0.081 | 29 | 36 | 5 | 11.0 | 0.004 |

| Acetic acid | −0.24 | −0.16 | 0.94 | 0.0 | 0.865 | 4.29 | 4.02 | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.373 |

| Propionic acid | −0.026 | −0.014 | 0.048 | 0.3 | 0.613 | 0.105 | 0.103 | 0.031 | 0.0 | 0.894 |

| Butyric acid | −0.006 | −0.001 | 0.015 | 0.6 | 0.459 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.1 | 0.804 |

| Isovaleric acid | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.022 | 0.3 | 0.567 | 0.181 | 0.174 | 0.014 | 1.1 | 0.322 |

| (B) | ||||||||||

| No Kiwifruit Control Start | No Kiwifruit Control End | Kiwifruit Start | Kiwifruit End | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Dietary fibre intake g/day (n = 20) | 33 | 8.9 | 29 | 13.4 | 33 | 13.4 | 36 | 13.4 | ||

| Acetic acid (n = 20) | 4.47 | 1.16 | 4.16 | 1.43 | 4.27 | 0.939 | 4.07 | 0.63 | ||

| Propionic acid (n = 20) | 0.132 | 0.076 | 0.100 | 0.054 | 0.116 | 0.040 | 0.106 | 0.06 | ||

| Butyric acid (n = 20) | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.018 | 0.037 | 0.018 | 0.036 | 0.03 | ||

| Isovaleric acid (n = 20) | 0.180 | 0.054 | 0.180 | 0.031 | 0.179 | 0.049 | 0.175 | 0.02 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishra, S.; Bentley-Hewitt, K.; McGhie, T.; Fraser, K.; Hedderley, D.; Martell, S.; Dinnan, H.; Monro, J. Effects of Daily Ingestion of Two SunGold Kiwifruit for 6 Weeks on Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Exploratory Intervention Study. Foods 2023, 12, 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234236

Mishra S, Bentley-Hewitt K, McGhie T, Fraser K, Hedderley D, Martell S, Dinnan H, Monro J. Effects of Daily Ingestion of Two SunGold Kiwifruit for 6 Weeks on Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Exploratory Intervention Study. Foods. 2023; 12(23):4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234236

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishra, Suman, Kerry Bentley-Hewitt, Tony McGhie, Karl Fraser, Duncan Hedderley, Sheridan Martell, Hannah Dinnan, and John Monro. 2023. "Effects of Daily Ingestion of Two SunGold Kiwifruit for 6 Weeks on Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Exploratory Intervention Study" Foods 12, no. 23: 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234236

APA StyleMishra, S., Bentley-Hewitt, K., McGhie, T., Fraser, K., Hedderley, D., Martell, S., Dinnan, H., & Monro, J. (2023). Effects of Daily Ingestion of Two SunGold Kiwifruit for 6 Weeks on Metabolic and Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Exploratory Intervention Study. Foods, 12(23), 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234236