The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

2.2. Data Collection Method

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Household

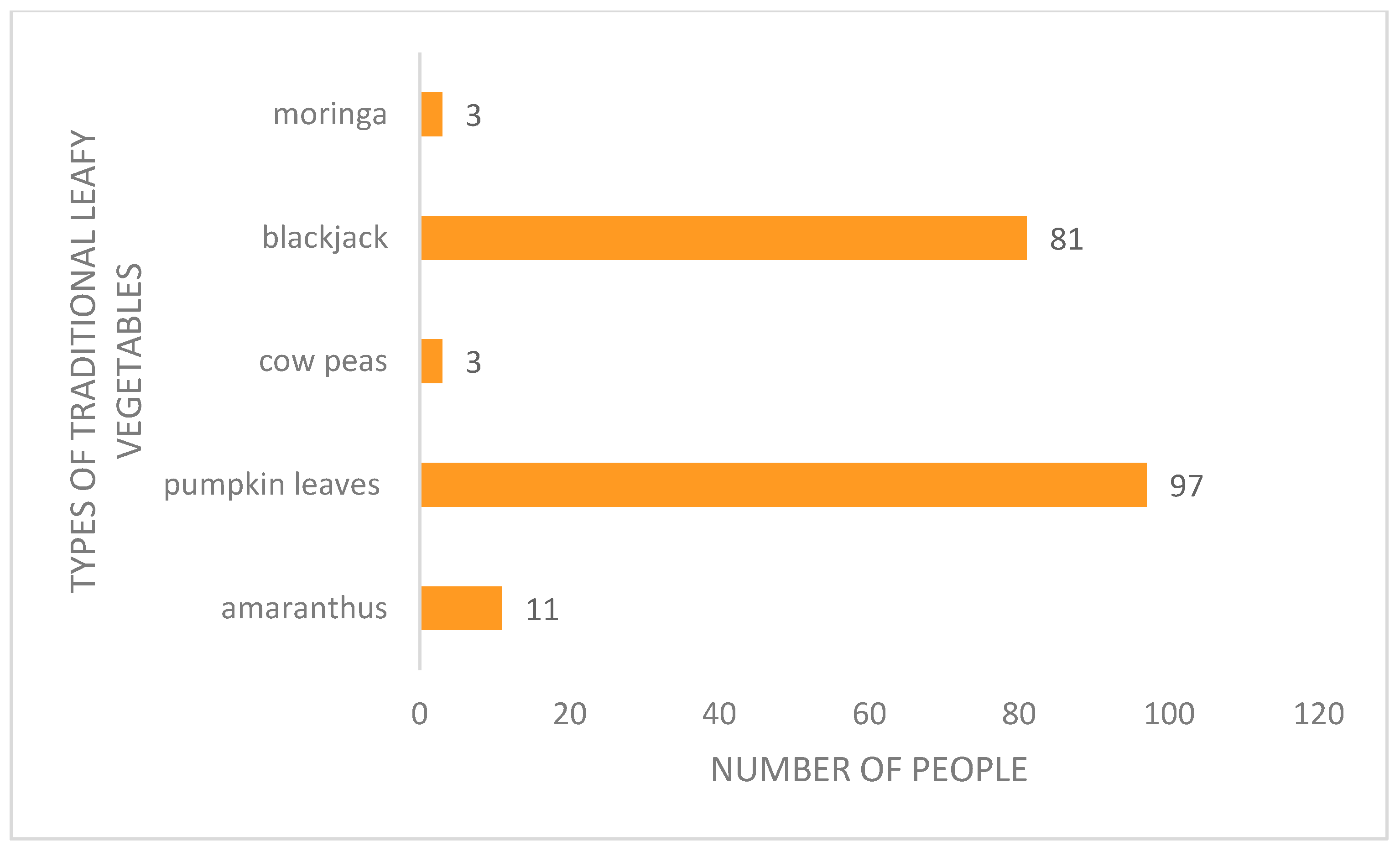

3.2. Types of Traditional Leafy Vegetables Consumed

3.3. Household Food Security Status of Surveyed Households

3.4. The Contribution of Traditional Leafy Vegetables to Household Food Security

3.5. Empirical Estimates of TLVs’ Contribution to Household Food Security Status

4. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). The Extent of Food Security in South Africa. 2017. Available online: http://www.StatsSa.gov.za (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Burnett, C. Framing a 21st century case for the social value of sport in South Africa. Sport Soc. 2021, 24, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhorat, H.; Lilenstein, A.; Monnakgotla, J.; Thornton, A.; van der Zee, K. Crime and Inequality in South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ctw/wpaper/202001.html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Population Estimates in South Africa. 2020. Available online: http://www.StatsSa.gov.za (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Azzarri, C.; Signorelli, S. Climate and poverty in Africa South of the Sahara. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, M.M.; Pizzinelli, C.; Perrelli, M.R. Household Consumption Volatility and Poverty Risk: Case Studies from South Africa and Tanzania; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aliber, M. Exploring Statistics South Africa’s national household surveys as sources of information about household-level food security. Agrekon 2009, 48, 384–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduniyi, O.S.; Tekana, S.S. Status and socioeconomic determinants of farming households’ food security in ngaka modiri molema district, South Africa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, M.; Daviaud, E.; Pattinson, R.; Fonn, S.; Lawn, J.E. Saving the lives of South Africa’s mothers, babies, and children: Can the health system deliver? Lancet 2009, 374, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisanya, S.O.; Hendriks, S.L. The contribution of community gardens to food security in the Maphephetheni uplands. Dev. South. Afr. 2011, 28, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, S.L. The food security continuum: A novel tool for understanding food insecurity as a range of experiences. In Food Security and Child Malnutrition; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gockowski, J.; Mbazo’o, J.; Mbah, G.; Moulende, T.F. African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Policy 2003, 28, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekesa, B.; Rao, E.J.O.; Cadilhon, J.J.; Ayebare, P.; Bashaasha, B.; Muyanja, C.; Tenywa, M.M.; Tumusiime, D.; Twinamasiko, J.; Jagwe, J.; et al. A Situational Analysis of Agricultural Production and Marketing, and Natural Resource Management Systems in the Central Region of Uganda. ILRI Proj. Rep. 2015. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/73336/PR_uganda_analysis.pdf?sequence=5 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- HJ, V.I.; van Rensburg Willem, J.; Van Zijl, J.J.B.; Sonja, L.V. The importance of traditional leafy vegetables in South Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2007, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vorster, H.H.; Kruger, A. Poverty, malnutrition, underdevelopment and cardiovascular disease: A South African perspective. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2007, 18, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Taruvinga, A.; Nengovhela, R. Consumers’ perceptions and consumption dynamics of African leafy vegetables (ALVs): Evidence from Feni communal area, Eastern Cape province, South Africa. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Technology (ICBET 2015), IPCBEE, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 10–11 March 2015; Volume 18, pp. 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.; Kessy, R.; Rajendran, S.; Samali, S. How promoting consumption of traditional African vegetables affects household nutrition security in Tanzania. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Van Jaarsveld, P.J.; Wenhold, F.A.M.; Van Rensburg, J. African leafy vegetables consumed by households in the Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. South Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 23, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mncwango, N.; Mavengahama, S.; Ntuli, N.; Van Jaarsveld, C. Diversity, consumption dynamics and ethnomedical claims of traditional leafy vegetables consumed by a rural community in the KwaMbonambi area, northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent Development Plan. Umdoni Municipality. 2018/2019. Available online: http://www.umdoni.gov.za (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S.; Sun, J. Business Research Methods; Mcgraw-hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 9, pp. 1–744. [Google Scholar]

- Kabalo, B.Y.; Gebreyesus, S.H.; Loha, E.; Lindtjørn, B. Performance of an adapted household food insecurity access scale in measuring seasonality in household food insecurity in rural Ethiopia: A cohort analysis. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogg, C.C.; Edward, S.S. Statistical Models for Ordinal Variables; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Otekunrin, O.A. Investigating food insecurity, health and environment-related factors, and agricultural commercialization in Southwestern Nigeria: Evidence from smallholder farming households. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 51469–51488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; Version 3; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, H.; Meyer, F.; Schönfeldt, H.C. A basic healthy food basket approach to evaluate the affordability of healthy eating in South Africa and Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1181683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, S.S.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Determinants of consumers’ acceptance of indigenous leafy vegetables in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondi, N.T.B.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Impact of Market Participation of Indigenous Crops on Household Food Security of Smallholder Farmers of South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngidi, M.S.C.; Zulu, S.S.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Effect of Consumers’ Acceptance of Indigenous Leafy Vegetables and Their Contribution to Household Food Security. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arene, C.J.; Anyaeji, R.C. Determinants of food security among households in Nsukka Metropolis of Enugu State, Nigeria. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Legwaila, G.M.; Mojeremane, W.; Madisa, M.E.; Mmolotsi, R.M.; Rampart, M. Potential of Traditional Food Plants in Rural Household Food Security in Botswana. 2011. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/JHF/article-abstract/71261EE1385 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Mavengahama, S.; McLachlan, M.; De Clercq, W. The role of wild vegetable species in household food security in maize based subsistence cropping systems. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Twine, W.; Patterson, L. “Locusts are now our beef”: Adult mortality and household dietary use of local environmental resources in rural South Africa1. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 35, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepe, T. Beyond the numbers: Understanding the value of vegetation to rural livelihoods in Africa. Geoforum 2008, 39, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojeremane, W.; Tshwenyane, S. Azanza garckeana: A valuable edible indigenous fruit tree of Botswana. Pak. J. Nutr. 2004, 3, 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Jman Redzic, S. Wild edible plants and their traditional use in the human nutrition in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2006, 45, 189–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, W. Food security situation in northern Ghana, coping strategies and related constraints. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 3, 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fentahun, M.T.; Hager, H. Exploiting locally available resources for food and nutritional security enhancement: Wild fruits diversity, potential and state of exploitation in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, K.; Shackleton, C.M.; Swallow, B.M.; Dassanayake, W. Impacts of HIV/AIDS on food consumption and wild food use in rural South Africa. Food Secur. 2016, 8, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C.M. Food insecurity in South Africa: To what extent can social grants and consumption of wild foods eradicate hunger? World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Variable Definition |

|---|---|

| Age | Age of the household member (in years) |

| Gender | Gender of the household head (1 = male, 0 = female) |

| Marriage | Marital status of the household head (1 = married, 0 = otherwise) |

| Household size | Number of family members (continuous) |

| Level of education | Level of education of the head in years (continuous) |

| Employment status | If the household is working (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Source of income | Income received by households |

| Occupation type | Type of employment a household is involved in |

| Participants | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| N = 100 | |

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 41 |

| Female | 59 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Single | 67 |

| Married | 26 |

| Other | 7 |

| Ethnic group (%) | |

| African | 96 |

| Other | 4 |

| Highest education level (%) | |

| None | 9 |

| Primary | 34 |

| Secondary | 54 |

| Tertiary | 3 |

| Employment status (%) | |

| Employed | 30 |

| Unemployed | 70 |

| Occupation type (%) | |

| Farm worker | 18 |

| Other | 12 |

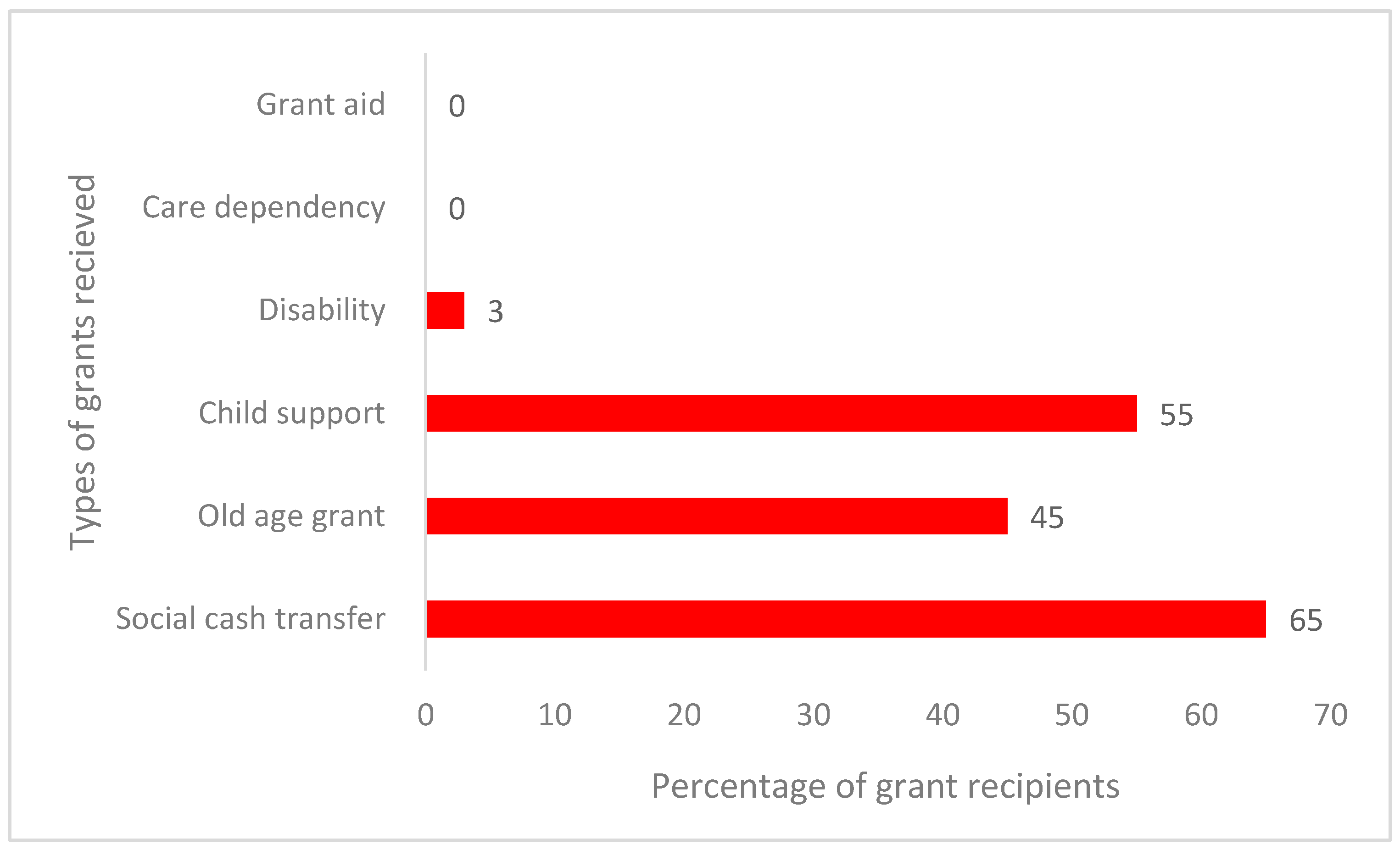

| Sources of income (%) | |

| Full-time employment | 24 |

| Part-time employment | 6 |

| Social grants | 68 |

| Farming | 6 |

| Remittance | 0 |

| Nonagricultural enterprise | 2 |

| Nothing | 11 |

| Monthly expenditure on food: ZAR | |

| ≤1000 | 80 |

| >1000 | 20 |

| Monthly expenditure on other necessities: ZAR | |

| ≤1000 | 91 |

| >1000 | 9 |

| Food Security Status of Respondents (%) | |

|---|---|

| Food secure | 17 |

| Mildly food insecure | 44 |

| Moderately food insecure | 26 |

| Severely food insecure | 13 |

| Food Secure | Food Insecure | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amarathus | |||

| Nonconsumer | 82.35 | 90.36 | 0.336 |

| Consumer | 17.65 | 9.6 | |

| Pumpkin | |||

| Nonconsumer | 0 | 3.61 | 0.426 |

| Consumer | 100 | 96.39 | |

| Cowpeas | |||

| Nonconsumer | 88.24 | 98.8 | 0.02 ** |

| Consumer | 11.76 | 1.2 | |

| Blackjack | |||

| Nonconsumer | 47.06 | 13.25 | 0.001 *** |

| Consumer | 52.94 | 86.75 | |

| Moringa | |||

| Nonconsumer | 88.24 | 98.8 | 0.02 ** |

| Consumer | 11.76 | 1.2 |

| HFIAS_Category | Coef. | St. Err. | p-Value | dydx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.695 | 1.561 | 0.277 | 0.245 |

| Age | −0.044 | 0.094 | 0.641 | 0.456 |

| HH_Head | −2.115 | 1.891 | 0.263 | 0.342 |

| Marital status | 2.551 | 1.104 | 0.021 ** | 0.016 ** |

| Educational level | −4.413 | 1.787 | 0.014 ** | 0.034 ** |

| Race | −22.342 | 2058.767 | 0.991 | 0.641 |

| Employment status | −1.139 | 0.474 | 0.016 ** | 0.025 ** |

| Main source of income | −0.121 | 1.820 | 0.947 | 0.8454 |

| Consumption of leafy vegetables | −8.781 | 5.063 | 0.083 * | 0.063 * |

| cut1 | −59.037 | 4117.551 | ||

| cut2 | −48.093 | 4117.538 | ||

| cut3 | −45.364 | 4117.537 | ||

| Mean dependent var | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.553 | |||

| Chi2 | 44.621 | |||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.000 | |||

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 64.117 | |||

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 83.734 | |||

| VIF | 4.23 | |||

| Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity | 0.876 | |||

| Chi2(1) | 1.44 | |||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngidi, M.S.C. The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Foods 2023, 12, 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213918

Ngidi MSC. The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Foods. 2023; 12(21):3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213918

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgidi, Mjabuliseni Simon Cloapas. 2023. "The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa" Foods 12, no. 21: 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213918

APA StyleNgidi, M. S. C. (2023). The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Foods, 12(21), 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213918