A Best–Worst Measure of Attitudes toward Buying Seabream and Seabass Products: An Application to the Island of Gran Canaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Best–Worst Scaling (BWS)

Implementation of the BWs

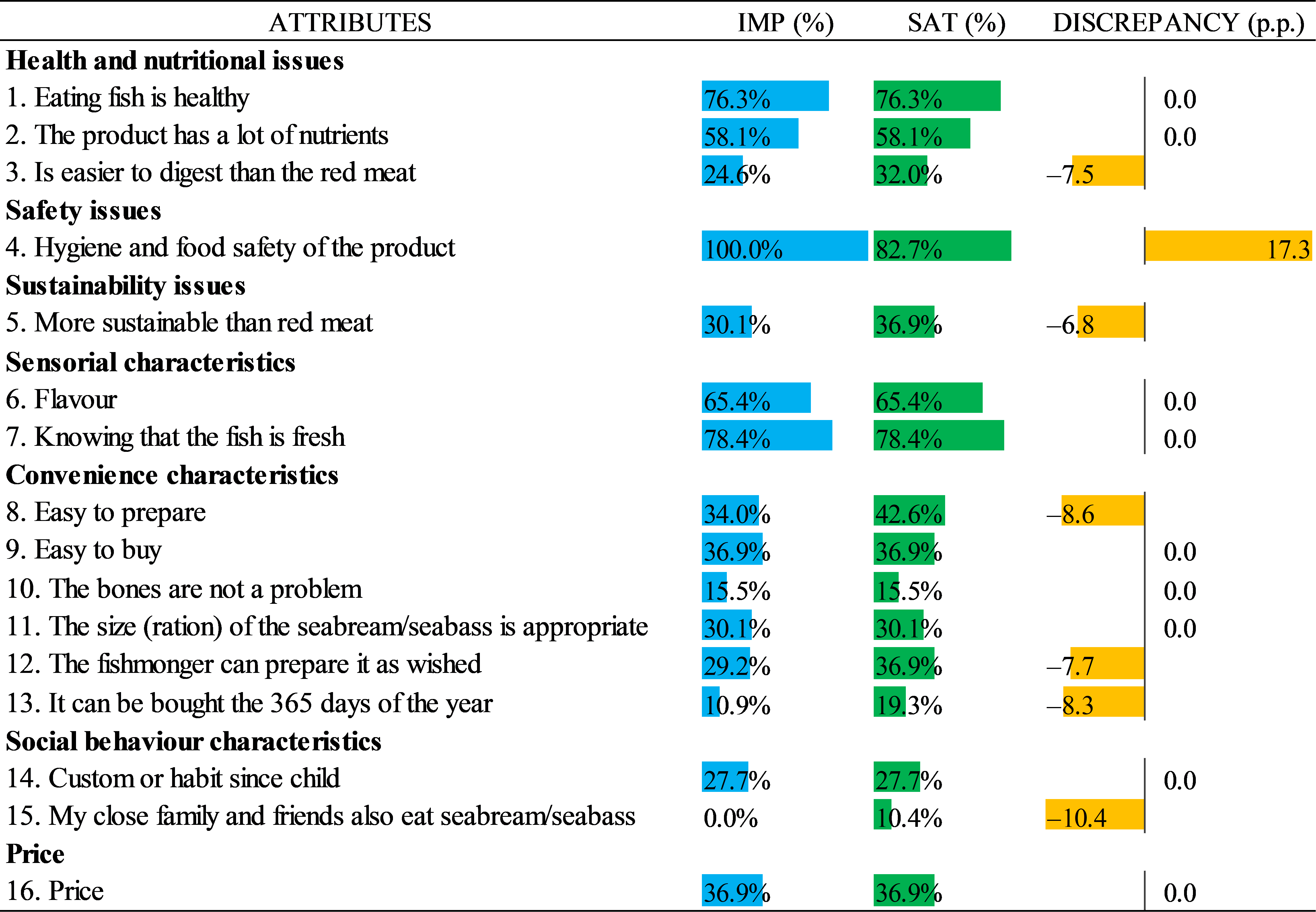

2.2. Importance–Satisfaction Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rating Scale Results

3.2. Best–Worst Scale Results

3.3. Comparing the Approaches

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Block 1 | ||||

| Scenario | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | Alternative 4 |

| 1 | Attribute 2 | Attribute 6 | Attribute 8 | Attribute 9 |

| 2 | Attribute 1 | Attribute 6 | Attribute 7 | Attribute 16 |

| 3 | Attribute 1 | Attribute 2 | Attribute 10 | Attribute 12 |

| 4 | Attribute 2 | Attribute 15 | Attribute 11 | Attribute 5 |

| 5 | Attribute 4 | Attribute 7 | Attribute 10 | Attribute 13 |

| 6 | Attribute 4 | Attribute 8 | Attribute 16 | Attribute 12 |

| 7 | Attribute 14 | Attribute 16 | Attribute 10 | Attribute 11 |

| 8 | Attribute 14 | Attribute 9 | Attribute 7 | Attribute 3 |

| 9 | Attribute 6 | Attribute 11 | Attribute 3 | Attribute 12 |

| 10 | Attribute 1 | Attribute 15 | Attribute 3 | Attribute 13 |

| Block 2 | ||||

| 1 | Attribute 15 | Attribute 8 | Attribute 9 | Attribute 10 |

| 2 | Attribute 15 | Attribute 7 | Attribute 5 | Attribute 12 |

| 3 | Attribute 1 | Attribute 14 | Attribute 8 | Attribute 5 |

| 4 | Attribute 4 | Attribute 6 | Attribute 14 | Attribute 15 |

| 5 | Attribute 8 | Attribute 7 | Attribute 11 | Attribute 13 |

| 6 | Attribute 1 | Attribute 4 | Attribute 9 | Attribute 11 |

| 7 | Attribute 4 | Attribute 2 | Attribute 16 | Attribute 3 |

| 8 | Attribute 6 | Attribute 10 | Attribute 5 | Attribute 3 |

| 9 | Attribute 2 | Attribute 14 | Attribute 12 | Attribute 13 |

| 10 | Attribute 9 | Attribute 16 | Attribute 5 | Attribute 13 |

| Attributes | IMP | t-Stat | p-Value | SAT | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and nutritional issues | ||||||

| (1) Eating fish is healthy | 1.54 | 16.31 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 16.82 | 0.00 |

| (2) The product has a lot of nutrients | 0.860 | 9.6 | 0.00 | 0.742 | 8.8 | 0.00 |

| (3) Is easier to digest than the red meat | −0.553 | −6.5 | 0.00 | −0.202 | −2.42 | 0.02 |

| Safety issues | ||||||

| (4) Hygiene and food safety of the product | 2.46 | 25.17 | 0.00 | 1.78 | 20.38 | 0.00 |

| Sustainability issues | ||||||

| (5) More sustainable than red meat | −0.337 | −3.91 | 0.00 | −0.155 | −1.86 | 0.06 |

| Sensorial characteristics | ||||||

| (6) Flavour | 1.06 | 12.25 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 12.99 | 0.00 |

| (7) Knowing that the fish is fresh | 1.66 | 17.8 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 17.44 | 0.00 |

| Convenience characteristics | ||||||

| (8) Easy to prepare | −0.182 | −2.11 | 0.03 | 0.222 | 2.67 | 0.01 |

| (9) Easy to buy | −0.0997 | −1.18 | 0.24 | 0.100 | 1.20 | 0.23 |

| (10) The bones are not a problem | −0.982 | −11.39 | 0.00 | −0.778 | −9.23 | 0.00 |

| (11) The size (ration) of the seabream/seabass is appropriate | −0.413 | −4.79 | 0.00 | −0.199 | −2.35 | 0.02 |

| (12) The fishmonger can prepare it as wished | −0.367 | −4.14 | 0.00 | −0.0310 | −0.36 | 0.72 |

| (13) It can be bought the 365 days of the year | −1.10 | −12.41 | 0.00 | −0.696 | −8.15 | 0.00 |

| Social behaviour characteristics | ||||||

| (14) Custom or habit since child | −0.500 | −5.76 | 0.00 | −0.315 | −3.78 | 0.00 |

| (15) My close family and friends also eat seabream/seabass | −1.54 | −16.61 | 0.00 | −1.05 | −11.83 | 0.00 |

| Price | ||||||

| (16) Price | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- |

| Alternative specific constants (ASCs) | Value | t-stat | p-value | |||

| ASC1 | 0.172 | 5.44 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC2 | 0.133 | 4.39 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC3 | 0.166 | 5.74 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC4 | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- | |||

| Goodness of fit | ||||||

| McFadden’s pseudo R2(ρ2) | 0.195 | |||||

| Adjusted McFadden’s pseudo R2 (Adjusted ρ2) | 0.193 | |||||

| Final Log-likelihood | −14,039.592 | |||||

| Number of observations | 14,040 | |||||

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsil, P.; Ardiansyah; Yanto, T. Consumers’ Intention and Behaviour towards Fish Consumption: A Conceptual Framework. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 255, p. 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2005, 44, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredahl, L.; Grunert, K.G. Determinants of the consumption of fish and shellfish in Denmark: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. In Proceedings of the International Seafood Conference: Seafood from Producer to Consumer, Integrated Approach to Quality, Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands, 13–16 November 1995; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, A.; Dávalos, J.; Hernani-Merino, M.; Higuchi, A.; Dávalos, J.; Hernani-Merino, M. Theory of planned behavior applied to fish consumption in modern Metropolitan Lima. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 37, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O. Antecedents of Seafood Consumption Behavior. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2004, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, N.T.; Olsen, S.O. Attitude toward and Consumption of Fish in Vietnam. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2012, 18, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, M.; Matulić, D.; Jelić, M. What determines fresh fish consumption in Croatia? Appetite 2016, 106, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O.; Thao, D.T.; Anh, N.T.K. The role of norms in explaining attitudes, intention and consumption of a common food (fish) in Vietnam. Appetite 2008, 51, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Orlando, FL, USA, 1993; p. 794. ISBN 978-0-15-500097-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Lawley, M.; Hamblin, D. Drivers and barriers to seafood consumption in Australia. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsø, K.; Verbeke, W.; Olsen, S.O.; Jeppesen, L.F. Motives, barriers and quality evaluation in fish consumption situations: Exploring and comparing heavy and light users in Spain and Belgium. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gempesaw, C.M.; Bacon, R.; Wessells, C.R.; Manalo, A. Consumer Perceptions of Aquaculture Products. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 77, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O. Consumer involvement in seafood as family meals in Norway: An application of the expectancy-value approach. Appetite 2001, 36, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rortveit, A.W.; Olsen, S.O. Combining the role of convenience and consideration set size in explaining fish consumption in Norway. Appetite 2009, 52, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrland, Ø.; Trondsen, T.; Johnston, R.S.; Lund, E. Determinants of seafood consumption in Norway: Lifestyle, revealed preferences, and barriers to consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2000, 11, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, D.; Nocella, G.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F.; Nardone, G. Consumer purchasing behaviour towards fish and seafood products. Patterns and insights from a sample of international studies. Appetite 2015, 84, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO Yearbook. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2018/FAO Annuaire. Statistiques des Pêches et de L’aquaculture 2018/FAO anuario. Estadísticas de Pesca y Acuicultura 2018; FAO Yearbook of Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-133371-6. [Google Scholar]

- EUMOFA. The EU Fish Market, 2020th ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-15377-1. [Google Scholar]

- FEAP European Aquaculture Production Report 2008–2016. Available online: http://feap.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/production-report-2017_web.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- APROMAR La Acuicultura en España. Available online: http://apromar.es/sites/default/files/2019/InformeAcui/APROMAR%20Informe%20ACUICULTURA%202019%20v-1-2.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Rodríguez Feijoo, S.; Rodríguez Mireles, S.; Lopez-Valcarcel, B.G.; Serra Majem, L.; Rodriguez Caro, A.; Pinilla Domínguez, J.; Hernández Yumar, A.; Barber Pérez, P. Alimentación y Salud. Distribución, Mercados y Precios. Análisis Detallado de Pescado, Frutas, Hortalizas y Legumbres (PFHL). 2018. Available online: https://accedacris.ulpgc.es/handle/10553/42364 (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- European Union. Special Eurobarometer 475: EU Consumer Habits Regarding Fishery and Aquaculture Products; Kantar Public: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-98186-9. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish National Institute of Statistics Población por Islas y Sexo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2910#!tabs-tabla (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J.J. Determining the Appropriate Response to Evidence of Public Concern: The Case of Food Safety. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; Rose, J.M. The best of times and the worst of times: A new best–worst measure of attitudes toward public transport experiences. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 86, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M.; Baumgartner, H. Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross-National Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.H.; Markowitz, P. Renewing market segmentation: Some new tools to correct old problems. In Proceedings of the ESOMAR 2002 Congress Proceedings, ESOMAR, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 10 November 2002; pp. 595–612. [Google Scholar]

- Marley, A.A.J. The best-worst method for the study of preferences. Cognit. Neuropsychol. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 11, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Marley, A.A.J.; Louviere, J.J. Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best-worst choices. J. Math. Psychol. 2005, 49, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlino, V.; Bora, D.; Verduna, T.; Massaglia, S. Household Behavior with Respect to Meat Consumption: Differences between Households with and without Children. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodice, L.W.; Norman, W.C. Comparing importance and confidence for production and source attributes of seafood among residents and tourists in South Carolina and Florida coastal communities. Appetite 2020, 146, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone, L.L. A law of comparative judgment. Psychol. Rev. 1927, 34, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.N.; Marley, A.A.J. Best-worst scaling: Theory and methods. In Handbook of Choice Modelling; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.J.; Hensher, D.A.; Swait, J.D.; Adamowicz, W. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.J.; Flynn, T.N.; Marley, A.A.J. Best-Worst Scaling: Theory, Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-107-04315-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bierlaire, M. BIOGEME: A free package for the estimation of discrete choice models. In Proceedings of the Swiss Transport Research Conference, Ascona, Switzerland, 19–21 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sever, I. Importance-performance analysis: A valid management tool? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, A.; Rial, J.; Varela, J.; Real, E. An application of importance-performance analysis (IPA) to the management of sport centres. Manag. Leis. 2008, 13, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. Correcting for Acquiescent Response Bias in the Absence of a Balanced Scale: An Application to Class Consciousness. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijters, B.; Cabooter, E.; Schillewaert, N. The effect of rating scale format on response styles: The number of response categories and response category labels. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Borra, D.; Peano, C.; Sottile, F.; Merlino, V.M. Consumer Preference Heterogeneity Evaluation in Fruit and Vegetable Purchasing Decisions Using the Best-Worst Approach. Foods 2019, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.; Louviere, J. The Best–Worst Scaling Approach: An Alternative to Schwartz’s Values Survey. J. Personal. Assess. 2008, 90, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Kapoor, S.; Moorthy, J. Buying behaviour of consumers for food products in an emerging economy. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Widmar, N.J.O. Aquaculture imports from Asia: An analysis of U.S. consumer demand for select food quality attributes. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Polanco, J.; Loose, S.M.; Luna, L. Are retailers’ preferences for seafood attributes predictive for consumer wants? Results from a choice experiment for seabream (Sparus aurata). Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2013, 17, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, R.; Sylvia, G. Willingness to Pay for Multiple Seafood Labels in a Niche Market. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2015, 30, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiri, M. Advances in traceability system: Consumer attitudes toward development of an integration method and quality control systems for the farmed Atlantic salmon. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual World Symposium of the International Food and Agribusiness Management Association, Frankfurt, Germany, 20–23 June 2011; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haghiri, M. An evaluation of consumers’ preferences for certified farmed Atlantic salmon. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Nam, J. The determinants of live fish consumption frequency in South Korea. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Krystallis, A.; Panagiotaki, P.; Theodorou, A.J. A marketing survey on Greek consumers’ attitudes towards fish. Aquac. Int. 2004, 12, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Lawley, M. Buying seafood: Understanding barriers to purchase across consumption segments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.E.; Amberg, S.M. Factors influencing consumption of farmed seafood products in the Pacific northwest. Appetite 2013, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, G.; Scarpa, R.; Cavicchi, A. Exploring consumer’s preferences for farmed sea bream. Aquac. Int. 2012, 20, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vermeir, I.; Brunsø, K. Consumer evaluation of fish quality as basis for fish market segmentation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovic, M.; Reinders, M.J.; Claret, A.; Guerrero, L.; Krystallis, A. A cross-cultural perspective on impact of health and nutrition claims, country-of-origin and eco-label on consumer choice of new aquaculture products. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.; Nayga, R.M. Is Marine Stewardship Council’s ecolabel a rising tide for all? Consumers’ willingness to pay for origin-differentiated ecolabeled canned tuna. Mar. Policy 2018, 96, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho Ribeiro, A.; Altintzoglou, T.; Mendes, J.; Nunes, M.L.; Dinis, M.T.; Dias, J. Farmed fish as a functional food: Perception of fish fortification and the influence of origin—Insights from Portugal. Aquaculture 2019, 501, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; House, L.; Gao, Z. Impacts of Nutrition Information on Choices of Fresh Seafood Among Parents. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2016, 31, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.A.; Pelletier, N.; Tyedmers, P. Preferences for health and environmental attributes of farmed salmon amongst southern ontario salmon consumers. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2011, 15, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Pan, M.; Hu, W.; Poerwanto, D. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Aquaculture Fish Products Vs. Wild-Caught Seafood—A Case Study in Hawaii. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2012, 16, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Olsen, S.B.; Nielsen, M.; Nielsen, R. The impact of animal welfare and environmental information on the choice of organic fish: An empirical investigation of German trout consumers. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2019, 34, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Olsen, S.B. Innovating out of the fishmeal trap: The role of insect-based fish feed in consumers’ preferences for fish attributes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. Sustainable Seafood From Aquaculture and Wild Fisheries: Insights From a Discrete Choice Experiment in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Hoffmann, J. Consumer preferences for farmed and ecolabeled turbot: A North German perspective. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2018, 22, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, F.A.; Quagrainie, K.K.; Chenyambuga, S. Consumer preferences for farmed tilapia in Tanzania: A choice experiment analysis. J. Appl. Aquac. 2016, 28, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Feucht, Y. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Seafood Made in Europe. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 30, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillo, J.; Martín, J.C.; Román, C. Discrete choice experiments in the analysis of consumers’ preferences for finfish products: A systematic literature review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claret, A.; Guerrero, L.; Ginés, R.; Grau, A.; Hernández, M.D.; Aguirre, E.; Peleteiro, J.B.; Fernández-Pato, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C. Consumer beliefs regarding farmed versus wild fish. Appetite 2014, 79, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency of Consumption | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Seafood and Fish | Seabream and Seabass | |

| At Home | Outside the Home | ||

| Never/Almost never | 1.1% | 15.1% | 9.4% |

| Sometimes in a year | 1.4% | 32.2% | 31.1% |

| Once a month | 4.3% | 22.8% | 23.7% |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 12.0% | 17.4% | 21.7% |

| Once a week | 43.3% | 10.5% | 11.1% |

| 2 or 3 times a week | 37.0% | 2.0% | 3.1% |

| Everyday | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Top Three Species Consumed | |||

| Species | Percentage | ||

| Tuna | 19.7% | ||

| Hake | 15.0% | ||

| Seabream | 12.9% | ||

| Salmon | 11.8% | ||

| Seabass | 8.6% | ||

| Sole | 7.2% | ||

| Cod | 5.8% | ||

| Mackerel | 4.8% | ||

| Wreckfish | 4.4% | ||

| Sama | 4.1% | ||

| Other | 5.8% | ||

| Locations to Buy Fish and Seafood (Several Options Possible) | |||

| Location | Percentage | ||

| Markets | 55.0% | ||

| Supermarkets | 86.0% | ||

| Fish companies | 1.1% | ||

| Fishers directly | 5.1% | ||

| Age Range | Maximum Education Level Reached | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–25 | 28.8% | Primary school | 1.4% |

| 26–35 | 18.5% | High school | 10.5% |

| 36–45 | 11.4% | Technician degree | 6.6% |

| 46–55 | 23.9% | University degree | 43.3% |

| 56 or older | 17.4% | University postgrad | 38.2% |

| Gender | Occupation | ||

| Male | 39.3% | Independent worker | 6.0% |

| Female | 60.7% | Public employee | 39.0% |

| Marital Status | Private sector employee | 14.3% | |

| Single | 47.9% | Student | 36.2% |

| Married | 34.8% | Unemployed | 2.0% |

| Living with a partner | 16.8% | Retired | 0.9% |

| Widow | 0.6% | Housekeeper | 1.7% |

| Income | |||

| Below national average | 13.7% | ||

| Around national average | 70.4% | ||

| Above national average | 16.0% | ||

| Attributes | Importance | Satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | Mean | Median | SD | |

| Health and nutritional issues | ||||||

| (1) Eating fish is healthy | 8.30 | 9 | 1.13 | 8.29 | 9 | 1.19 |

| (2) The product has many nutrients | 7.89 | 8 | 1.33 | 7.75 | 8 | 1.52 |

| (3) Is easier to digest than the red meat | 6.98 | 8 | 2.28 | 7.03 | 8 | 2.27 |

| Safety issues | ||||||

| (4) Hygiene and food safety of the product | 8.59 | 9 | 1.02 | 8.29 | 9 | 1.27 |

| Sustainability issues | ||||||

| (5) More sustainable than red meat | 6.68 | 7 | 2.18 | 6.74 | 7 | 2.17 |

| Sensorial characteristics | ||||||

| (6) Flavour | 7.99 | 8 | 1.30 | 7.76 | 8 | 1.46 |

| (7) Knowing that the fish is fresh | 8.09 | 9 | 1.39 | 7.98 | 9 | 1.52 |

| Convenience characteristics | ||||||

| (8) Easy to prepare | 6.72 | 7 | 1.83 | 6.91 | 7 | 1.89 |

| (9) Easy to buy | 7.10 | 7 | 1.69 | 7.16 | 7 | 1.78 |

| (10) The bones are not a problem | 5.81 | 6 | 2.63 | 6.01 | 7 | 2.56 |

| (11) The size (ration) of the seabream/seabass is appropriate | 6.73 | 7 | 1.78 | 6.82 | 7 | 1.79 |

| (12) The fishmonger can prepare it as wished | 7.14 | 8 | 1.93 | 7.23 | 8 | 1.88 |

| (13) It can be bought 365 days of the year | 6.56 | 7 | 2.18 | 6.69 | 7 | 2.14 |

| Social behaviour characteristics | ||||||

| (14) Custom or habit since child | 6.93 | 7 | 2.06 | 6.47 | 7 | 2.38 |

| (15) My close family and friends also eat seabream/seabass | 5.51 | 6 | 2.28 | 5.49 | 6 | 2.33 |

| Price | ||||||

| (16) Price | 7.45 | 8 | 1.60 | 7.21 | 7 | 1.80 |

| Attributes in Which the Importance and Satisfaction (IMP–SAT) are the Same | ||||||

| Attributes | IMP–SAT | t-Stat | p-Value | |||

| Health and nutritional issues | ||||||

| (1) Eating fish is healthy | 1.55 | 27.36 | 0.00 | |||

| (2) The product has many nutrients | 0.833 | 16.63 | 0.00 | |||

| Sensorial characteristics | ||||||

| (6) Flavour | 1.12 | 22.03 | 0.00 | |||

| (7) Knowing that the fish is fresh | 1.63 | 30.14 | 0.00 | |||

| Convenience characteristics | ||||||

| (10) The bones are not a problem | −0.839 | −16.9 | 0.00 | |||

| (11) The size (ration) of the seabream/seabass is appropriate | −0.269 | −5.52 | 0.00 | |||

| Social behaviour characteristics | ||||||

| (14) Custom or habit since child | −0.363 | −7.43 | 0.00 | |||

| Attributes in Which the Importance (IMP) and Satisfaction (SAT) Differ | ||||||

| Attributes | IMP | t-stat | p-value | SAT | I-stat | p-value |

| Health and nutritional issues | ||||||

| (3) Is easier to digest than the red meat | −0.485 | −7.02 | 0.00 | −0.191 | −2.89 | 0.00 |

| Safety issues | ||||||

| (4) Hygiene and food safety of the product | 2.48 | 30.39 | 0.00 | 1.8 | 25.31 | 0.00 |

| Sustainability issues | ||||||

| (5) More sustainable than red meat | −0.268 | −3.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- |

| Convenience characteristics | ||||||

| (8) Easy to prepare | −0.113 | −1.73 | 0.08 | 0.226 | 3.59 | 0.00 |

| (9) Easy to buy | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- |

| (12) The fishmonger can prepare it as wished | −0.302 | −4.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- |

| (13) It can be bought 365 days of the year | −1.02 | −14.46 | 0.00 | −0.693 | −10.46 | 0.00 |

| (15) My close family and friends also eat seabream/seabass | −1.45 | −19.94 | 0.00 | −1.04 | −15.59 | 0.00 |

| Price | ||||||

| (16) Price | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- |

| Alternative specific constants (ASCs) | Value | t-stat | p-value | |||

| ASC1 | 0.178 | 5.64 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC2 | 0.131 | 4.38 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC3 | 0.161 | 5.62 | 0.00 | |||

| ASC4 | 0.00 | -fixed- | -fixed- | |||

| Goodness of fit | ||||||

| McFadden’s pseudo R2(ρ2) | 0.194 | |||||

| Adjusted McFadden’s pseudo R2 (Adjusted ρ2) | 0.193 | |||||

| Final Log-likelihood | −14,053.504 | |||||

| Number of observations | 14,040 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cantillo, J.; Martín, J.C.; Román, C. A Best–Worst Measure of Attitudes toward Buying Seabream and Seabass Products: An Application to the Island of Gran Canaria. Foods 2021, 10, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010090

Cantillo J, Martín JC, Román C. A Best–Worst Measure of Attitudes toward Buying Seabream and Seabass Products: An Application to the Island of Gran Canaria. Foods. 2021; 10(1):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010090

Chicago/Turabian StyleCantillo, Javier, Juan Carlos Martín, and Concepción Román. 2021. "A Best–Worst Measure of Attitudes toward Buying Seabream and Seabass Products: An Application to the Island of Gran Canaria" Foods 10, no. 1: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010090

APA StyleCantillo, J., Martín, J. C., & Román, C. (2021). A Best–Worst Measure of Attitudes toward Buying Seabream and Seabass Products: An Application to the Island of Gran Canaria. Foods, 10(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010090