Language Preferences in Romanian Communication Sciences Journals: A Web-Based Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Scientific Journal Publishing in Contemporary Romania

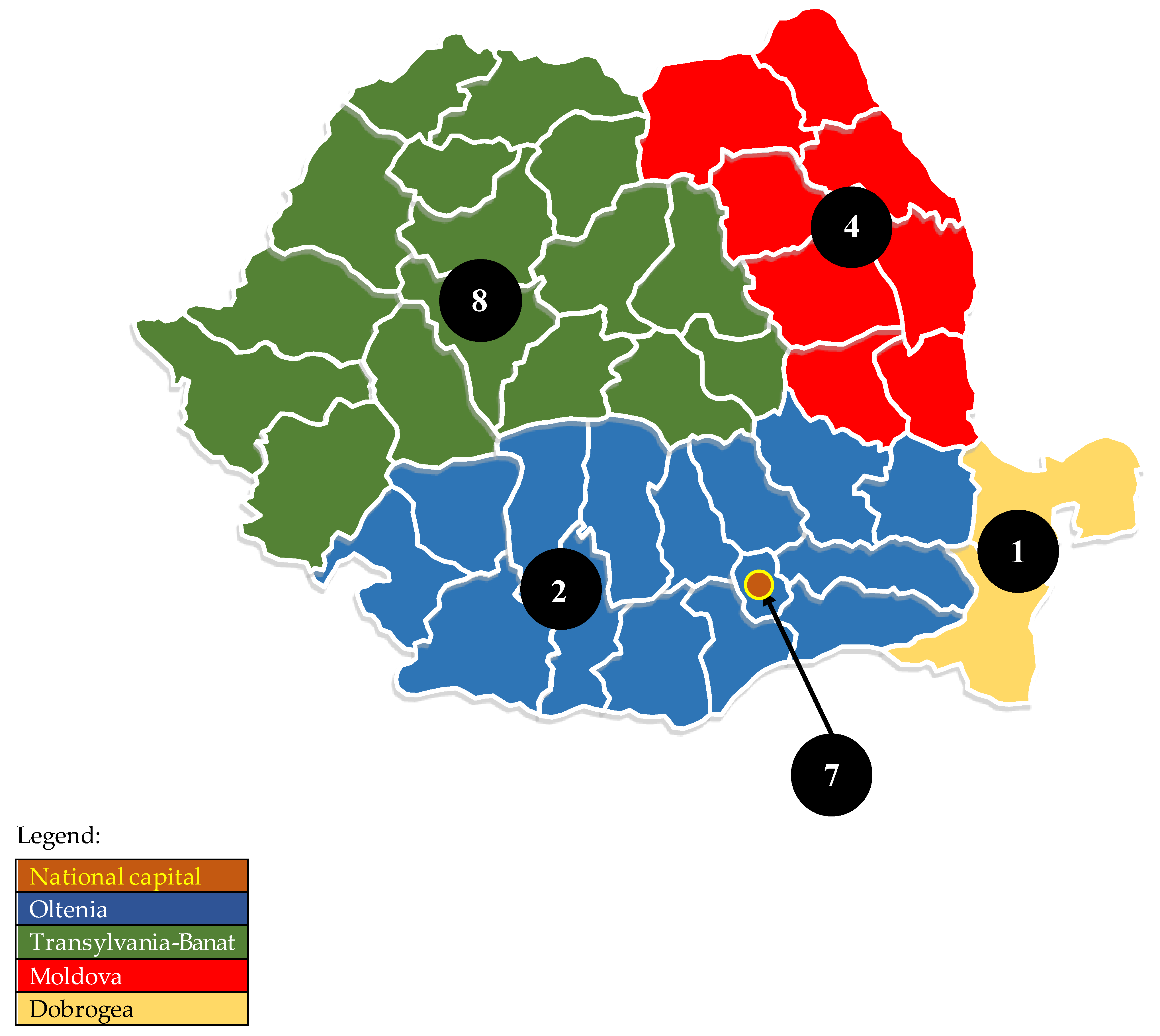

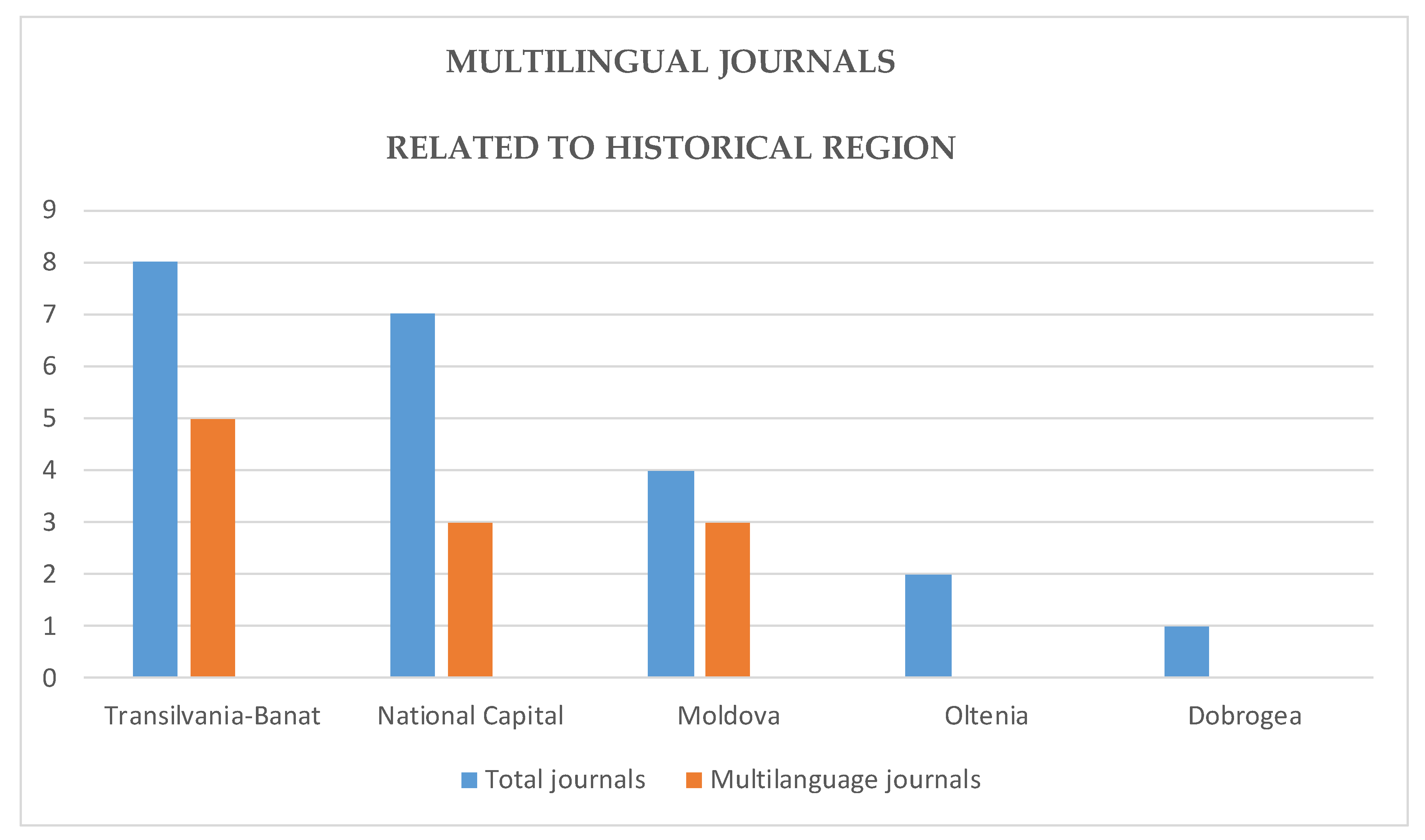

3.2. Monolingual or Bi-/Multilingual? Scientific Journals and Linguistic Preferences by Historical Regions

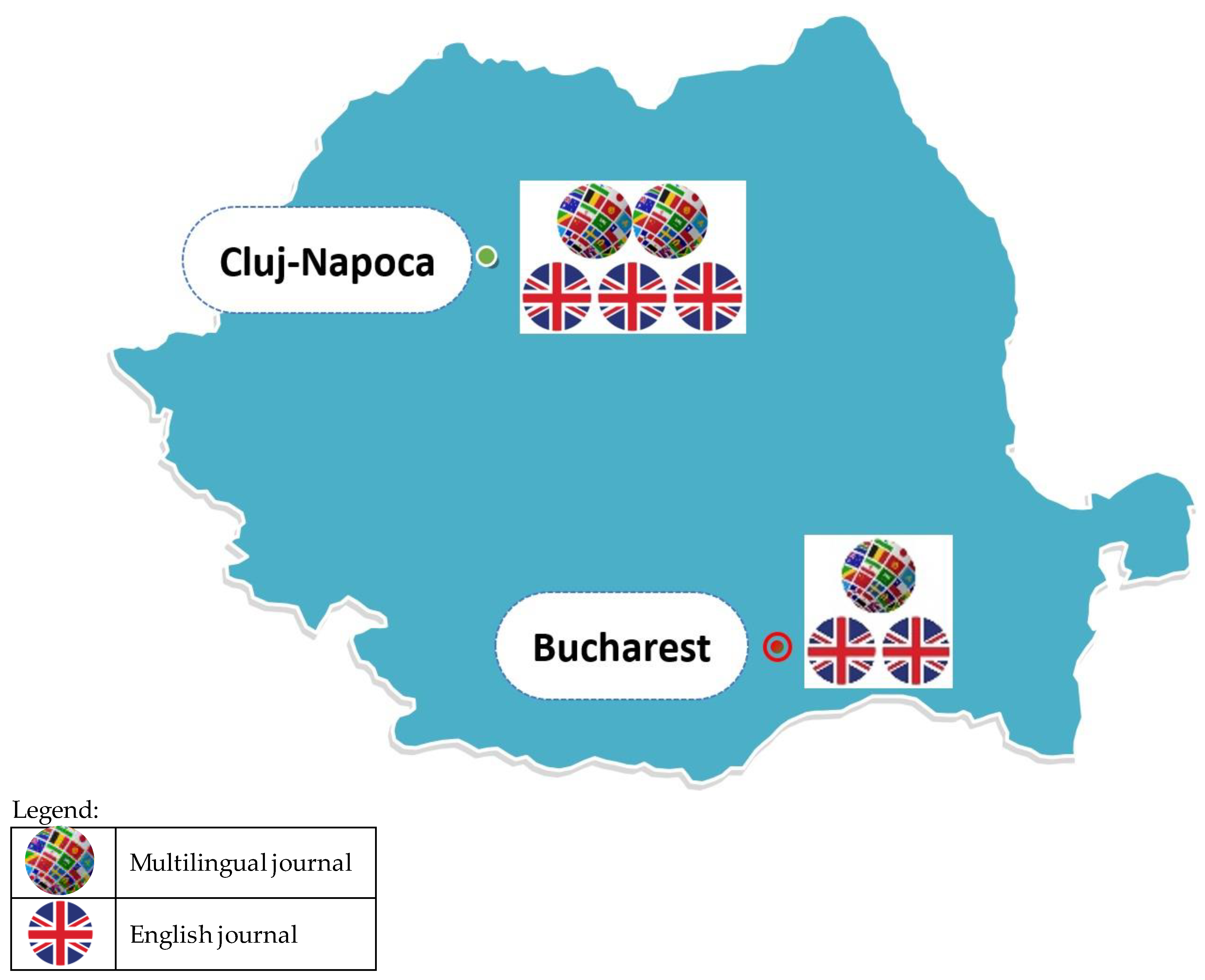

3.3. Poles of Science

4. Conclusions and Further Directions of Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| http://www.acta.sapientia.ro/acta-comm/communicatio-main.htm |

| http://www.acta.sapientia.ro/acta-film/film-main.htm |

| https://www.aucjc.ro/about/ |

| https://dppd.tuiasi.ro/cercetare/buletinul-ipi-sectia-socio-umane/ |

| http://lsc.rs.utcb.ro/index.html |

| https://revistacil.wordpress.com/ |

| https://www.cultural-intertexts.com/ |

| https://www.ekphrasisjournal.ro/index.php?p=home |

| http://litere.hyperion.ro/hypercultura/ |

| http://icsr.unibuc.ro/ |

| http://anale.spiruharet.ro/index.php/behav-sci/index |

| https://www.mrjournal.ro/ |

| https://www.medok.ro/en/medok/about-medok |

| https://sc.upt.ro/ro/publicatii/pcts |

| http://www.jurnalism-comunicare.eu/rrjc/index_en.php |

| https://journalofcommunication.ro/index.php/journalofcommunication |

| https://revistasaeculum1943.wordpress.com |

| https://sserr.ro/ |

| http://studia.ubbcluj.ro/serii/ephemerides/ |

| https://journalonarts.org/ |

| http://stylesofcomm.fjsc.unibuc.ro/home |

| https://www.techniumscience.org/index.php/socialsciences/about |

References

- Banks, D. Thoughts on Publishing the Research Article over the Centuries. Publications 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swales, J.M. English as Tyrannosaurus rex. World Engl. 1997, 16, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, C. The role of English in scientific communication: Lingua franca or Tyrannosaurus rex? J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2004, 3, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuteeva, M.; McGrath, L. Taming Tyrannosaurus rex: English use in the research and publication practices of humanities scholars in Sweden. Multilingua 2014, 33, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, D. English as the lingua franca of international publishing. World Engl. 2018, 37, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, C. On the Conceptual History of the Term Lingua Franca. Apples J. Appl. Lang. Stud. 2015, 9, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, M.C.; Porras, A.M. Science Communication in Multiple Languages Is Critical to Its Effectiveness. Front. Commun. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, N.; Larivière, V. Je Veux Bien, Mais Me Citerez-Vous? On Publication Language Strategies in An Anglicized Research Landscape. In Proceedings of the Communication Presented at the International Conference on Science and Technology Indicators, Valence, Spain, 14–16 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini, R.; Packer, A.L. Is there science beyond English? Initiatives to increase the quality and visibility of non-English publications might help to break down language barriers in scientific communication. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salager-Meyer, F. Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2008, 7, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.A.; Pozzebon, M. How to resist linguistic domination and promote knowledge diversity? Rev. Adm. Empresas 2013, 53, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitskaya, L.; Tikhonova, E. Multilingualism in Russian journals: A controversy of approaches. Eur. Sci. Ed. 2019, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annex to Ministerial Order 6129/2016 on Minimum Necessary and Obligatory Standards for Conferring Didactic Titles in Higher Education, Professional Research and Development Degrees, the Quality of Doctoral Supervisor and the Habilitation Certificate. pp. 64–66. Available online: http://www.cnatdcu.ro/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/anexa-ordin-6.129_2016-standarde-minimale_0.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- European Commission Press Release. President Barroso Presents the Commissioner Designate for Romania. 30 October 2006. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_06_1499 (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Sivertsen, G. Balanced multilingualism in science. In BiD: Textos Universitaris de Biblioteconomia i Documentació; University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Volume 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salager-Meyer, F. Writing and publishing in peripheral scholarly journals: How to enhance the global influence of multilingual scholars? J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2014, 13, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernicova-Buca, M. The New Babylon: The World in the 21st Century. Scientific Bulletin of the “Politehnica” University of Timisoara. Trans. Mod. Lang. 2010, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczycki, E.; Engels, T.C.E.; Pölönen, J.; Bruun, K.; Dušková, M.; Guns, R.; Nowotniak, R.; Petr, M.; Sivertsen, G.; Starčič, A.I.; et al. Publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities: Evidence from eight European countries. Scientometrics 2018, 116, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J. Academic Publishing in English: Exploring Linguistic Privilege and Scholars’ Trajectories. J. Lang. Identit. Educ. 2019, 18, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hertog, P.; Jager, C.-J.; Vankan, A.; Te Velde, R.; Veldkamp, J.; Aksnes, D.; Sivertsen, G.; Van Leeuwen, T.; Van Wijk, E. Science, Technology & Innovation Indicators. Thematic Paper 2: Scholarly Publication Patterns in the Social Sciences and Humanities and Their Relationship with Research Assessment. 2014. Available online: http://dialogic.nl/documents/other/sti2_themepaper2.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Central and Eastern Online Library (CEEOL). Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Index Copernicus. Available online: https://journals.indexcopernicus.com/ (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J. Inf. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.R.; Roloff, M.E.; Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R. What is Communication Science? In The Handbook of Communication Science; SAGE Publications Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palea, A. Identitatea Profesionala a Specialistilor în Relații Publice [Professional Identity of Public Relations Specialists]; Tritonic: Bucharest, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coravu, R.; Constantinescu, M. A Study in Gold: Top Romanian Scholarly Journals and Their Open Access Policies. Rom. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 14, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situatia Curenta a Revistelor Recunoscute CNCSIS [The Current Status of Journals Recognized by the National University Research Council]. 2011. Available online: https://uefiscdi.gov.ro/articole/1991/Situatia-curenta-a-revistelor-recunoscute-CNCSIS-2011.html (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Sīle, L.; Guns, R.; Sivertsen, G.; Engels, T. European Databases and Repositories for Social Sciences and Humanities Research Output: Report (July). 2017. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5172322 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Florian, R.; Florian, N. Majoritatea Revistelor Ştiinţifice Româneşti nu Servesc Ştiinţa [The majority of Romanian Scientific Journals do not Serve Science]. Ad. Astra. 2006, 5, 1–26. Available online: http://www.ad-astra.ro/journal/9/florian_reviste_locale.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Gelan, V.E. Dezmățul în Limbi Străine al Revistelor Academice Românești de Filosofie [The Deception in Foreign Languages of Romanian Academic Journals of Philosophy]. 16 July 2014. Available online: https://www.contributors.ro/dezma%c8%9bul-in-limbi-straine-al-revistelor-academice-romane%c8%99ti-de-filosofie/ (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Muresan, L.-M.; Pérez-Llantada, C. English for research publication and dissemination in bi-/multiliterate environments: The case of Romanian academics. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2014, 13, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociatia Romana de Relatii Publice [Romanian Association of Public Relations]. Educatie [Study Programs in Communication Sciences]. Available online: http://arrp.eu/educatie/ (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Ware, M.; Mabe, M. The STM Report: An Overview of Scientific and Scholarly Journals Publishing; International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2009; Available online: www.stm-assoc.org/2009_10_13_MWC_STM_Report.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Law 1/2011. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geztsobvgi/statutul-personalului-didactic-lege-1-2011?dp=gq2tomryge2da (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Metodologia de Evaluare și Clasificare a Editurilor, Colecțiilor și Revistelor Științifice, în Vederea Recunoașterii și Clasificării din Partea Consiliului Național al Cercetării Științifice a Revistelor Științifice și Editurilor din Domeniul Fundamental al Științelor Umaniste (Aprobată Prin OM 5550/11.09.2020) [Methodology of Evaluating and Classifying Publishing Houses, Collections and Scientific Journals by the National Research University Council for the Major Domain of Humanities, Approved by Ministerial Order 5550/11.09.2020]. Available online: http://www.cncs-nrc.ro/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Anexa_OMEC_5550_11_09_2020.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Deca, L.; Egron-Polak, E.; Fiţ, C.R. Internationalisation of Higher Education in Romanian National and Institutional Contexts. In Higher Education Reforms in Romania; Curaj, A., Deca, L., Egron-Polak, E., Salmi, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Swittzerland, 2015; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

| Journal | City | Scientific Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Cluj | theoretical and empirical research in communication studies, with a focus on information society issues |

| Cluj | film and media |

| Craiova | journalism, communication, and management |

| Iasi | language and literature (applied linguistics, literary studies, theatrical and cinematic discourse, foreign language learning/teaching, translation studies); social sciences (education, psychology, philosophy, communication studies) |

| Bucharest | humanistic debates (SSH) |

| Galati | SSH |

| Galati | SSH |

| Cluj | cinema, media, and cultural studies |

| Bucharest | literature (print and hypertext), media studies (radio, television), film studies, visual and performative arts, teaching (language, literature, rhetoric) |

| Bucharest | information and communication sciences |

| Bucharest | history of communication and behavioral sciences, the professional practice of communication, psychology, cognitive science, and anthropology, communication and behavioral sciences training and education, and communication and behavioral sciences practice and new technology |

| Cluj | media and communication |

| Cluj | history of journalism, contemporary media analyses, studies on the general problem of communication |

| Timisoara | communication + translation studies + didactics of foreign languages |

| Bucharest | communication studies |

| Bucharest | communication studies |

| Sibiu | social sciences and humanities |

| Craiova | universe of social sciences |

| Cluj | communication studies |

| Iasi | arts and communication |

| Bucharest | communication studies |

| Constanta | humanities + social sciences (among which is communication studies) |

| Nr. Journal | Web Pages lg | Publication lg | Abstract LG | +Abstract lg | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 2. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 3. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 4. | EN | EN | FR | ART LG | +RO | |||||||

| 5. | EN | EN | FR | GE | ESP | ART LG | ||||||

| 6. | EN | RO | FR | EN | RO | FR | ART LG | +EN/FR for RO | ||||

| 7. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 8. | EN | FR | EN | ART LG | ||||||||

| 9. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 10. | EN | RO | FR | EN | EN+RO+FR | |||||||

| 11. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 12. | EN | EN | ART LG | +EN | ||||||||

| 13. | EN | HU | EN | RO | HU | EN+RO | ||||||

| 14. | EN | EN | FR | GE | ART LG | +EN | ||||||

| 15. | EN | RO | EN | FR | GE | ESP | ART LG | +EN | ||||

| 16. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 17. | EN | RO | EN | RO | FR | GE | EN | |||||

| 18. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 19. | EN | RO | EN | EN | ||||||||

| 20. | EN | EN | FR | ESP | ART LG | +EN | ||||||

| 21. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

| 22. | EN | EN | EN | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cernicova-Buca, M. Language Preferences in Romanian Communication Sciences Journals: A Web-Based Analysis. Publications 2021, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010011

Cernicova-Buca M. Language Preferences in Romanian Communication Sciences Journals: A Web-Based Analysis. Publications. 2021; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleCernicova-Buca, Mariana. 2021. "Language Preferences in Romanian Communication Sciences Journals: A Web-Based Analysis" Publications 9, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010011

APA StyleCernicova-Buca, M. (2021). Language Preferences in Romanian Communication Sciences Journals: A Web-Based Analysis. Publications, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010011