Abstract

The transition from print to digital information has transformed the role of academic libraries, which have had to redefine themselves as intermediaries and partners in the learning and research processes. This study analyzes the evolution and current provision of research support services in Spanish academic libraries through an analysis of the three strategic plans published by the Spanish association of academic libraries (REBIUN) and a survey administered to the library directors. Results show that academic libraries are firmly embedded within universities’ research activities, and that most of them depend on vice-rectorates for research or scientific policy. There is a relationship between the size of the library and its provision of research support services, although no correlation is observed between the size of the library and the staff devoted to research support. Library directors stress the value of institutional repositories, a vision also reflected in the importance assigned to open access in the strategic plans. Other current hot topics, such as data management, do not seem to be among the priorities of Spanish library directors as yet.

1. Introduction

The mission of academic libraries is to support teaching and research at their home institutions. Traditionally, library support for research has revolved around “information discovery, collection development and some elements of information management” [1] (p. 33). However, the context in which academic libraries provide these services has changed dramatically in recent years; the transition from print to digital information has transformed their role as intermediaries. Researchers no longer build their workflow around the library as they used to in the past, and many library functions are now perceived as less valuable than they were in the print world [2]. As a result, library directors feel “increasingly less valued by, involved with, and aligned strategically with their supervisors and other senior academic leadership” [3].

These transformations are having an impact on the delivery of library research support services. Hoffman [4] (p. XIV) defines research support as “anything that a library does that supports the activity of scholarship and research at its parent institution”. In this article, following Bent [5], by research support services we mean library staff interventions in the research lifecycle, including, but not limited to, identifying funding opportunities, searching literature, advising on data management plans, creating researcher identifiers, advising on dissemination, tracking citations, etc.

Delaney and Bates [6] urge that academic libraries should rethink their roles to embrace a more participatory and collaborative approach, with librarians becoming partners in the learning and research processes. Academic libraries have realized that, in order to remain relevant, they should not merely react to changes [7]. If in the past academic libraries focused on managing documents, they should now evolve towards becoming service providers facilitating their users’ activities. This approach involves the examination of how researchers work in order to identify the steps and tasks in which the library can provide value throughout the research lifecycle [8]. Following this line of thought, in the new LIBER strategic plan for the period 2018 to 2022, “the main area of focus that has been chosen is digital open services supporting research” [9] (p. 3).

So far, the literature analyzing this shift of academic libraries towards a new partnership role has put greater emphasis on issues such as research data management and bibliometrics. Research data management “concerns the organization of data, from its entry to the research cycle through to the dissemination and archiving of valuable results. It aims to ensure reliable verification of results, and permits new and innovative research built on existing information” [10]. A survey of 140 libraries in Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the United Kingdom [11] showed that most of them offered or planned bibliometric services, with a lower level of engagement in research data management, although a greater involvement in the future was anticipated. The main constraints on the development of research support services were knowledge and skills gaps among library staff and a lack of confidence surrounding their expected roles in both data management and bibliometrics [12].

When asked, library users express willingness to receive services of this kind. A survey among education faculty members [13] showed that they required more support for grant activity, data management, intellectual property management and bibliometric analysis. The interest in supporting scholars in research assessment processes was reflected in the fact that by 2015 nearly all library websites of the Association of American Universities (AAU) members had web pages or LibGuides providing information on indicators and metrics to assist scholars in making a case for themselves and for their work [14]. Similarly, Ryś and Chadaj [15] report that bibliometric processes have become a vital part of library work in Poland. Gutzman et al. [16] recently analyzed the experiences of seven US and Canadian medical libraries in providing research evaluation support services for their users. Despite the diversity of service models and the variety of products and services provided, the implementation of these services allowed libraries to expand their roles and to contribute more directly to the research missions of their institutions.

In the case of research data management, in spite of their impact on the library agenda, the level of development of support services seems to be lower. Cox et al. [17] surveyed libraries in Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the United Kingdom and found an increasing maturity of data management services, although more in advisory and support roles than in technical roles. This is consistent with the results of Tenopir et al. [18] who showed that European libraries tend to offer, or are planning to offer, consultative or reference research data services rather than technical or hands-on services.

In Spain, academic libraries have undergone major changes in the past few decades. In 1983, the University Reform Act was passed in order to build a new university model based on democracy, autonomy and a scientific approach as opposed to the authoritarian, dirigiste and centralized model inherited from the years of the dictatorship [19]. In the 1980s, the academic library did not exist as an organized university service; at best, universities had only a set of fragmented departmental or campus libraries. The subsequent vision of a unified “university library service” over the past 20 years has allowed Spanish universities to build modern, efficient library services matching European standards, which have gone far beyond the expectations of the beginning of the 1980s [20].

During the 1980s and the 1990s, Spanish academic libraries set themselves three main objectives: the coordination of resources in a single library service, automation, and the construction of new buildings [21,22]. This thrust helped libraries to overcome some of the problems related to the lack of recognition at University management levels, the dispersion of collections in academic departments, and the lack of resources in terms of staff, budget or equipment. Due to their historical development and the lack of resources for acquisitions, during the 20th century Spanish academic libraries became rich in heritage collections but were clearly deficient in terms of current materials. Because these libraries have focused on preserving heritage collections rather than on creating new collections, they have not traditionally enrolled subject librarians in their staff. Bibliographical databases, for instance, were not generally present in library collections until the mid-1990s.

For their part, University teaching methods are mostly based on exams, not on essays. Collection building in Spanish academic libraries has been traditionally informed by teaching staff who have been responsible for the selection process, while librarians have largely played a passive role. Library research support used to focus on managing journal subscriptions, and more precisely on administrative aspects rather than selecting titles. With the arrival of electronic journals, libraries acquired a leading role in negotiating licenses, although at a consortial rather than at an individual level. In summary, historical circumstances have created a gap between libraries and researchers. Scholars used to visit libraries to use materials, especially academic journals, but would not expect to be offered services to support their research tasks. The figure of the subject librarian, acting as a liaison between the library and academic departments, was missing; libraries have played a passive role even in pivotal tasks such as collection development.

Some authors have recently called for the creation of bibliometric units in academic libraries [23] and for a stronger library role in supporting research evaluation [24]. A recent survey [25] concluded that 85% of Spanish academic libraries offer research support services, mostly in the areas of training, document delivery, reference and repositories. Additionally, other services such as training on issues related to open access and intellectual property, remote access to electronic resources, and research evaluation, are provided in partnership with other University departments.

This research aims to investigate the current provision of research support services in Spanish academic libraries. Specifically, the study is underpinned by the following research questions:

- How has the provision of library research support services evolved in the past fifteen years (2003–2018) as observed in the strategic plans of the Spanish association of academic libraries (henceforth, REBIUN, its acronym in Spanish)?

- What resources do Spanish academic libraries devote to research support?

- What research support services do library directors value the most?

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in two stages. First, the three strategic plans published by REBIUN were analysed to determine the presence of research support services among library goals. REBIUN was founded in 1988, when a cooperative library project was created involving nine Spanish public universities. Currently, the association includes 76 academic libraries plus the library of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). To date, the association has produced three strategic plans covering the periods 2003–2006 [26], 2007–2011 [27] and 2012–2020 [28].

The second stage of the research consisted of an online survey administered to the 76 directors of the academic libraries that are members of REBIUN. The survey was distributed using an internal mailing list. An initial message with a link to the online questionnaire was e-mailed on 22 January 2018 and a reminder was sent on 11 February 2018. When the questionnaire was closed, on 4 April 2018, 55 replies had been collected, forming a response rate of 75%.

3. Results

3.1. Research Support Services in REBIUN’s Strategic Plans

REBIUN has played a key role in directing the recent evolution of Spanish academic libraries. Its definition of the library as a functional unit, as opposed to a dispersed group of collections, was decisive. Its ‘guidelines’ [29] set the parameters for new library services and buildings, and in recent years its ‘strategic plans’ have oriented the development of Spanish academic libraries. Below, we analyze the extent to which these strategic plans have included research support among library services.

The first strategic plan of REBIUN [26] embraced the period between 2003 and 2006. The plan was organized into five strategic lines: building a new model of academic libraries as a resource centre for learning and research; promoting the development of technology in libraries; offering multidisciplinary electronic information; improving the training of library staff; and defining a model for the organization of the group [30]. The plan comprised a set of 13 actions, but just one was devoted to research support. At that time, REBIUN’s concerns focused primarily on its own operation and in offering a modern image of the academic library that would favor investments in much needed library buildings. Consortia had undertaken the management of electronic subscriptions, and the open access movement had not yet become established.

The second strategic plan [27], which covered the period between 2007 and 2011, was organized in four strategic lines including, for the first time, one devoted to research. The other three strategic lines referred to learning, quality, and the organization of the group. The plan comprised 26 actions, three of them devoted to research support. Although some of the actions aimed to create a digital library of scholarly journals or to work on intellectual property issues, in practical terms most efforts were devoted to repositories. In 2007, REBIUN and FECYT (the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology) signed an agreement for the creation of Recolecta, a web portal harvesting scholarly outputs stored in University institutional repositories. Recolecta was created in 2008, and its development and maintenance, as well as the improvement of institutional repositories, monopolized the group’s research support services [31] (pp. 11–12).

The third strategic plan is currently underway and will last until 2020. It is organized around four strategic lines: the organization of the REBIUN group; teaching and research support; digital libraries, Internet and social networks; and collaborative products and services. In this plan, 6 out of 28 actions focus on research support, mostly related to repositories and open access.

3.2. Current Provision of Research Support Services

In order to contrast the goals set out in REBIUN’s strategic plans with the current provision of research support services, a survey was conducted among REBIUN library directors. The results show that, from a managerial point of view, most academic libraries are embedded in University research activities. Thus, 60% of the libraries depend on a vice-rectorate for research or scientific policy. Among the remaining 40% there are examples of libraries merged with technological services (9%), dependent on vice-rectorates for culture (7%), or included in academic planning (5%), etc.

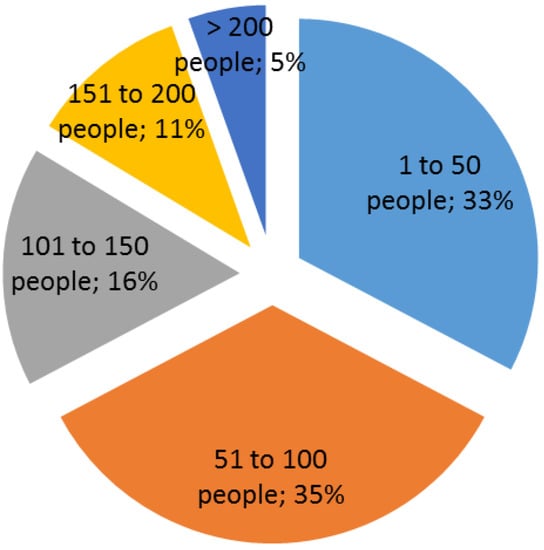

Spanish academic libraries vary considerably in terms of size. As shown in Figure 1, one-third of the libraries employ less than 50 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, another third between 51 and 100 FTE staff, and the final third more than 101 FTE staff. On average, each academic library employs 87 FTE librarians (median = 78). According to data provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education [32] for the public universities that replied to our survey (n = 40), there is a strong correlation (Pearson = 0.91) between the size of the university (in terms of number of students enrolled) and the size of the library (measured as FTE staff).

Figure 1.

Size of Spanish academic libraries in terms of staff.

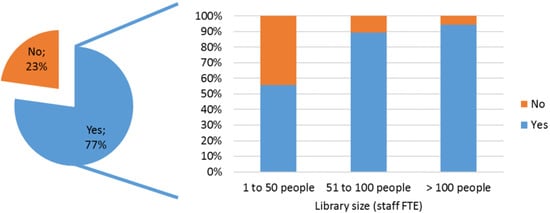

When asked whether their libraries provide research support services, 77% of the respondents replied affirmatively. As shown in Figure 2, the provision of research support services is closely related to the size of the library. Among small libraries (those with less than 50 FTE staff), 56% offer research support services. This percentage rises to 89% in medium-sized libraries (those with 51 to 100 FTE staff) and reaches 94% (i.e., all libraries but one) among large libraries (those with more than 100 FTE staff).

Figure 2.

Provision of research support services and relationship to library size.

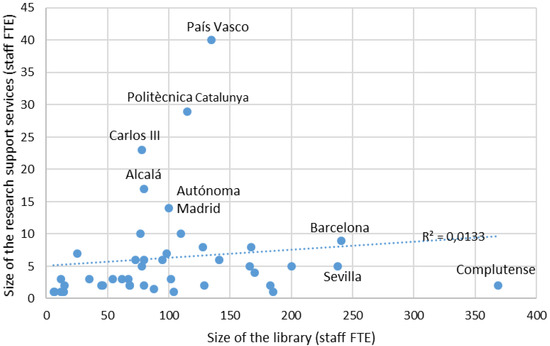

Although Figure 2 shows a relationship between the size of the library and the provision of research support services, no correlation is observed between the size of the library and the amount of staff devoted to research support services. Figure 3 shows that both small (bottom left of the figure) and large academic libraries (bottom right) devote less than 10 members of the staff to this activity. On the other hand, five libraries, all of them in the 50–150 FTE staff range, assign between 14 and 40 people to these tasks. On average, libraries devote 6.4 members of staff to research support services (median = 3).

Figure 3.

Relationship between size of the library and staff assigned to research support.

When asked about the existence of relationships with other University services related to research, 75% of the directors replied affirmatively. Most libraries have links with technology transfer offices (responsible for technology transfer and other aspects of the commercialization of research), research project management offices, graduate and doctoral schools, University presses, and bibliometric units.

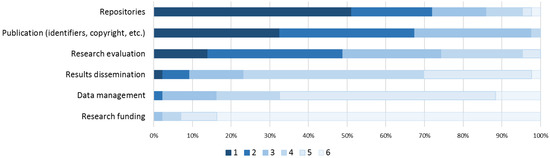

Library directors were asked to rate six research support services on a scale from 1 (most important) to 6 (least important). As shown in Figure 4, they considered institutional repositories to be by far the most important research support service: 51% ranked repositories as the most important research support service and 21% put them in second place. The second service by order of importance was that of providing assistance to researchers in the publication process (i.e., informing them of questions related to authors’ identifiers, intellectual property, etc.): 33% of the library directors ranked this service first and 35% second. In third place in the order of importance, library directors ranked services related to assisting researchers in evaluation processes (14% ranked them first and 35% second). Finally, providing assistance in results dissemination, data management and procurement of research funds aroused a much lower level of interest among library directors.

Figure 4.

Ranking of research support services by library directors.

Finally, when asked about the users targeted, nearly all directors stated that research support services are addressed both to teaching and research staff and to PhD students; half of them stated that these services are also addressed to university managers, deans, and heads of departments.

4. Discussion

The results of the study should be interpreted in the light of the history and evolution of Spanish academic libraries over the past few decades. It should also be borne in mind that the questionnaire was self-administered and that the results may be affected by social desirability bias.

The relationship between Spanish academic libraries and the research community has always been weak. Spanish university libraries are rich in heritage collections and have traditionally focused their efforts on the preservation of these special collections. Therefore, even though most libraries currently depend on vice-rectorates for research and scientific policy, we still find examples of academic libraries embedded in vice-rectorates devoted to cultural affairs, possibly a reflection of the heritage collections they store.

Spanish academic libraries have not traditionally included the figure of the reference librarian or subject librarian among their staff. This has had an impact on the current situation; even though nearly four of every five libraries state that they offer research support services, the human resources devoted to these tasks are scarce. Two-thirds of the libraries employ more than 50 FTE staff but, on average, fewer than seven librarians are devoted to research support, and just five libraries devote more than 10 librarians to research support. Currently, then, Spanish academic libraries lag behind some of their international counterparts; for instance, nearly half of the American library deans and directors surveyed by Ithaka [3] indicated that their libraries are increasing the share of staffing and budget devoted to services that support teaching, learning, and research. Specialized faculty research was among the positions for which respondents anticipate the most growth in the next five years.

In Spain, the size of the library correlates strongly with the size of the university. However, the amount of staff devoted to research support is not necessarily higher in bigger universities; in fact, middle-size universities are the ones that assign the most staff to research support. The age of universities may help to explain this apparent discrepancy. The ones that report devoting more staff to research support are relatively new universities, such as the País Vasco (founded in 1980), Politècnica de Catalunya (1971), Carlos III (1989), and Autónoma de Madrid (1968). Bigger universities are older, host large heritage collections, and possibly have less leeway for introducing changes in their services portfolio: clear examples are the universities of Barcelona (founded 1450), Sevilla (1505) and the Complutense (1822).

When asked about the importance assigned to different research support services, library directors value institutional repositories very highly. This vision concurs with the relevance assigned to open access in REBIUN’s strategic plans. The importance assigned to assisting researchers with the publication process and evaluations may be related to the strong bibliometric approach applied in research evaluation in Spain. Nevertheless, a similar focus in bibliometrics is also observed in academic library services based in other countries [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Current hot topics such as data management do not yet seem to be among the priorities of Spanish library directors. Our results are consistent with the information provided by sources such as re3data.org, a registry of research data repositories that covers various academic disciplines and countries. In November 2018, a search for “Spain” in re3data.org retrieved 24 repositories; however, most repositories are international projects, hosted somewhere else, with Spain being just one of the participating countries. Examples are the “European Archive of Historical EArthquake Data (AHEAD)”, the “European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA)”, the “International Service of Geomagnetic Indices”, and the “Italian Centre for Astronomical Archive”, all of which are listed under the entry “Spain” in re3data.org. In fact, just five of the listed repositories are institutional repositories of Spanish universities hosting data collections. However, Spanish academic libraries are probably not far behind their international counterparts, since the literature shows that most data services in academic libraries are mainly for consultation or reference, rather than of a technical nature [17,18].

5. Conclusions

The transition from print to digital information has transformed the ways in which academic libraries support teaching and research at their home institutions. Researchers no longer build their workflow around the library. If in the past academic libraries focused on managing documents, they should now evolve towards becoming service providers facilitating their users’ activities. In the case of research, this approach involves the examination of how scholars work in order to identify the steps and tasks in which the library can provide value throughout the whole research lifecycle.

Our research has sought to understand how this trend materializes in the provision of research support services in Spanish academic libraries, through an analysis of the strategic plans published by the Spanish association of academic libraries and a survey administered to their directors. The results show that the provision of research support services is mediated by a historically weak relationship between librarians and academics. As a result, resources devoted to these tasks are scarce and do not correlate with the size of the libraries. Most of the attention is paid to open access, especially institutional repositories, and hot topics such as data management do not yet figure among the priorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.B. and L.A.; Formal analysis, Á.B. and L.A.; Investigation, Á.B. and L.A.; Writing—original draft, Á.B. and L.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a presentation delivered at the 20th Fiesole Collection Development Retreat held in Barcelona, 25–27 April 2018, http://www.casalini.it/retreat/retreat_2018.asp.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Auckland, M. Re-Skilling for Research: An Investigation into the Role and Skills of Subject and Liaison Librarians Required to Effectively Support the Evolving Information Needs of Researchers; Research Libraries UK: London, UK, 2012; Available online: http://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/RLUK-Re-skilling.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Dempsey, L.; Malpas, C. Academic library futures in a diversified university system. In Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Gleason, N.W., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2018; pp. 65–89. ISBN 978-981-13-0194-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C. Ithaka S + R US Library Survey 2016. Available online: http://www.sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/SR_Report_Library_Survey_2016_04032017.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Hoffman, S. Introduction: A vision for supporting research. In Dynamic Research Support for Academic Libraries; Hoffman, S., Ed.; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2016; p. XIV. ISBN 978-1-78330-049-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, M.J. Practical Tips for Facilitating Research; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78330-017-4. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, G.; Bates, J. Envisioning the academic library: A reflection on roles, relevancy and relationships. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2015, 21, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, S.; Cox, A.M.; Rutter, S. Mapping the Future of Academic Libraries: A Report for SCONUL. Available online: https://sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/SCONUL%20Report%20Mapping%20the%20Future%20of%20Academic%20Libraries.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Bryant, R.; Clements, A.; Feltes, C.; Groenewegen, D.; Huggard, S.; Mercer, H.; Missingham, R.; Oxnam, M.; Rauh, A.; Wright, J. Research Information Management: Defining RIM and the Library’s Role; OCLC Research: Dublin, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIBER. Research Libraries Powering Sustainable Knowledge in the Digital Age: LIBER Europe Strategy 2018–2022. Available online: https://libereurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/LIBER-Strategy-2018-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Whyte, A.; Tedds, J. Making the Case for Research Data Management; Digital Curation Centre: Edinburgh, UK, 2011; Available online: http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/briefing-papers (accessed on 27 November 2018).

- Corrall, S.; Kennan, M.A.; Afzal, W. Bibliometrics and research data management services: Emerging trends in library support for research. Libr. Trends 2013, 61, 636–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, M.A.; Corrall, S.; Afzal, W. “Making space” in practice and education: Research support services in academic libraries. Libr. Manag. 2014, 35, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, C.V.; Schroeder, R. The impact of library support on Education faculty research productivity: An exploratory study. Behav. Soc. Sci. Libr. 2015, 34, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiter, A.M.; Moulaison, H.L. Supporting scholars: An analysis of academic library websites’ documentation on metrics and impact. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2015, 41, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryś, D.; Chadaj, A. Bibliometrics and academic staff assessment in Polish university libraries—Current trends. Liber Q. 2016, 26, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzman, K.E.; Bales, M.E.; Belter, C.W.; Chambers, T.; Chan, L.; Holmes, K.L.; Lu, Y.; Palmer, L.A.; Reznik-Zellen, R.C.; Sarli, C.C.; et al. Research evaluation support services in biomedical libraries. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.M.; Kennan, M.A.; Lyon, L.; Pinfield, S. Developments in research data management in academic libraries: Towards an understanding of research data service maturity. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 2182–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenopir, C.; Talja, S.; Horstmann, W.; Late, E.; Hughes, D.; Pollock, D.; Schmidt, B.; Baird, L.; Sandusky, R.J.; Allard, S. Research data services in European academic research libraries. Liber Q. 2017, 27, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglada, L.; Taladriz, M. Pasado, presente y futuro de las bibliotecas universitarias españolas. Arbor 1997, 617–618, 65–88. Available online: http://arbor.revistas.csic.es/index.php/arbor/article/viewArticle/1836 (accessed on 12 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.; Balagué, N.; Anglada, L. Evaluación y calidad en las bibliotecas universitarias: Experiencias españolas entre 1994–2006. Revista Española de Documentación Científica 2007, 30, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglada, L. Les Biblioteques Universitàries: Evolució, Tendències i Reptes de Futur. Bibliodoc: Anuari de Biblioteconomia, Documentació i Informació. pp. 53–62. Available online: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Bibliodoc/article/viewFile/16608/16449 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Anglada, L. Cambios y retos organizativos en las bibliotecas universitarias. In Conferencias Sobre Bibliotecas Universitarias; Biblioteca Universidad Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://biblioteca.ucm.es/descargas/documento4439.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Torres-Salinas, D.; Jiménez-Contreras, E. Hacia las unidades de bibliometría en las universidades: Modelo y funciones. Revista Española de Documentación Científica 2015, 35, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillo, I.F. Informetrics for librarians: Describing their important role in the evaluation process. El Profesional de la Información 2016, 25, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey Martín, C.; Camón Luis, E.; Pacheco, F. El soporte a la investigación en las bibliotecas universitarias españolas. Anales de Documentación 2018, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REBIUN. Plan Estratégico 2003–2006. Available online: http://campus.usal.es/~uso/webuso/CALIDAD%20Y%20MEJORA%20BIBLIOTECAS/REBIUN.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- REBIUN. II Plan Estratégico: 2007–2010. Available online: http://www.rebiun.org/node/278 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- REBIUN. III Plan Estratégico de REBIUN 2020. Available online: http://www.rebiun.org/node/277 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- REBIUN. Normas y Directrices para Bibliotecas Universitarias y Científicas: Colecciones; Ministerio de Educación y Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 1997; Available online: http://www.metodosdeinformacion.es/mei/index.php/mei/article/view/251/273 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Cabo, M.; Celestino, S.; Guerra, C.; Taladriz, M. Un pont cap al futur: El Plan Estratégico de REBIUN. BiD Textos Universitaris de Biblioteconomia i Documentació 2003, 10. Available online: http://bid.ub.edu/10cabo.htm (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- REBIUN. Informe Final: II Plan Estratégico 2007–2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11967/55 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- España: Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Estadísticas e Informes Universitarios. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano-mecd/estadisticas/educacion/universitaria.html (accessed on 27 November 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).