Abstract

This White Paper reports the outcome of a Workshop on “Research Data Service Discoverability” held in the island of Santorini (GR) on 21–22 April 2016 and organized in the context of the EU funded Project “RDA-E3”. The Workshop addressed the main technical problems that hamper an efficient and effective discovery of Research Data Services (RDSs) based on appropriate semantic descriptions of their functional and non-functional aspects. In the context of this White Paper, by RDSs are meant those data services that manipulate/transform research datasets for the purpose of gaining insight into complicated issues. In this White Paper, the main concepts involved in the discovery process of RDSs are defined; the RDS discovery process is illustrated; the main technologies that enable the discovery of RDSs are described; and a number of recommendations are formulated for indicating future research directions and making an automatic RDS discovery feasible.

1. Introduction

New high-throughput scientific instruments, telescopes, satellites, accelerators, supercomputers, sensor networks, and running simulations are generating massive amounts of research data. We are entering a new era characterized by the production of huge volumes of data. Big Data—datasets whose size is beyond the ability of typical database software tools to capture, store, manage, and analyze—are revolutionizing the way research is carried out, which results in the emergence of a new fourth paradigm of science based on data-intensive computing []. The new availability of huge amounts of data, along with advanced tools and services, offers a whole new way of understanding the world. Indeed, the inferential techniques (Big Data Analytics) being used on Big Data can offer great insight into many complicated issues. The quality of scientific research can potentially be improved by using advanced correlation techniques and analyzing data in better ways; data analysts can sift through massive swaths of data to predict conditions, behaviors, and events in ways unimagined only years earlier.

Instrumental in making this happen is the realization of the principles of Open Science, i.e., the sharing of results, ideas, methods, tools, services, and data between researchers much earlier and much more extensively than previously.

One of the challenges faced by researchers, in a globally networked scientific world, is to be able to discover research data services that fulfill their research needs. By Research Data Service (RDS) discoverability we mean the capability of automatically locating, in open and distributed environments, research data services that fulfill a researcher’s goals.

Making a research data service discoverable enables the service reuse. Service reuse has some important advantages: (i) it avoids replication of software that already exists; (ii) it makes savings as the software development is expensive; and (iii) it enables the development of composite research data services by combining existing research data services for the purpose of carrying out complex research tasks.

In addition, the data service discoverability facilitates the reproducibility of a research result. In fact, in order to reproduce a scientific result, it is necessary to know the exact version of the software used to generate that result.

The effectiveness and efficiency of the discovery of appropriate services and the possibility of composing them in order to build complex scientific workflows is a requirement of modern science.

The EC acknowledged the importance of this requirement and has inserted explicitly a request for making all the data services developed by EC-funded projects discoverable in the “Horizon 2020—Work Programme 2016-2017 (European Research Infrastructures (including e-Infrastructures))”:

“all services developed by projects should be made discoverable on-line, e.g. by including them in searchable catalogues or registries of (digital) research services with the metadata for describing and accessing the service”.

Enabling automated location of RDSs that adequately fulfil a given research need presents several technological challenges.

The objective of the Santorini Workshop was to address some of these challenges that hamper effective and efficient research data service discoverability.

This White Paper gathers the ideas presented and discussed by the participants in the Workshop and organizes them as an organic whole.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces and defines the main concepts involved in the discovery process of RDSs. Section 3 describes the scientific context within which an RDS operates. Section 4 describes the process of discovering RDSs. Section 5 describes the main technologies that enable the discovery of RDSs. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by presenting the main recommendations that emerged during the live discussions at the Workshop.

2. Concepts and Definitions

In this section the main concepts involved in the lifecycle of an RDS are introduced and defined.

2.1. Research Data

By research data we mean scientific or technical measurements, values calculated, and observations or facts that can be represented by numbers, tables, graphs, models, text, or symbols, and that are used as a basis for reasoning or further calculation []. Such data may be generated by various means, including observation, computation, or experimentation. Scientists regard data as accurate representations of the physical world and as evidence to support claims []. Data can be referred to as raw, verified, or derivative [] (Figure 1). Raw data consist of original observations, such as those collected by satellite and beamed back to earth or generated by an instrument or sensor or collected by conducting an experiment. For example, see National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) level 0 data []. Verified data are generated by curatorial activities. Their quality and accuracy have, thus, been assured. Derivative data are generated by processing activities. The raw data are frequently subject to subsequent stages of refinement and analysis, depending on the research objectives. For example, see NASA level 1 data [].

Figure 1.

Research Data Lifecycle.

2.2. Research Dataset

There is no single well-defined concept of research dataset. Informally speaking, we can think of a research dataset as a meaningful collection of research data that is published and maintained by a single provider, deals with a certain topic, and originates from a certain experiment/observation/process that was conducted for research purposes. According to the International Organization for Standards (ISO), a dataset is an “identifiable collection of data that may be accessed individually or in combination or managed as a whole entity”. In the context of the Linked Data world, by dataset is meant a set of Resource Description Framework (RDF) triples that are published, maintained, or aggregated by a single provider. A dataset, once accepted for deposit, is undergoing a registration process during which a “Digital Object Identifier” (DOI) is assigned to the dataset by a Registration Agency []. A research dataset, in order to be citable and (re)usable, must be accompanied by appropriate “metadata” information.

2.3. Description of a Research Data Service (RDS)

The description of a RDS should be expressive and detailed enough to enable RDS discovery with high precision and recall. At the same time, it should make the task of annotating an RDS as well as formulating a request feasible. At present, RDS descriptions do not or insufficiently capture the defining characteristics of an RDS: what does it do, how is it implemented, and how does it relate to other data and services?

Service descriptions are declarative descriptions of what is provided (output) and what is required (input) by the RDS they describe.

In cognitive science, it has become commonplace to separate three distinct levels of analysis of information processing systems []. We have adopted this approach in the description of an RDS. This three-level description of an RDS is appropriate as we need to know what an RDS is doing at a higher level in order to find out how at the lower level it accomplishes that task, that is, we need to know the function of the RDS being analyzed in order to know which lower- level properties are important to understanding the overall working of the RDS.

Understanding the behavior of an RDS requires knowing which aspects of the lower-level properties are significant in making a contribution to the overall behavior of the RDS; this depends on having some sense of the higher-level functioning of the RDS.

Therefore, we have identified the following three distinct levels at which an RDS should be described: computational, algorithmic, implementational.

At computational level:

- An RDS is a computation characterized as a mapping from one kind of information structure to another (input/output datasets).

- What the goal (functionality) is of the computation (RDS) is described.

- This goal is described as a relationship or dependency between input and output datasets.

In essence, at this level, the logic of the abstract computational model of the RDS is described. This is the level of what the RDS does. This level is the most abstract.

At algorithmic level:

- The representation of the input parameter (input dataset) is specified, i.e., the extensional and intensional information of the input dataset is specified.

- The representation of the output parameter (output dataset) is specified, i.e., the extensional and intensional information of the output dataset is specified.

- The pre-conditions, i.e., assertions about certain properties taken by the values of the input parameter before the RDS execution are specified.

- The post-conditions, i.e., assertions about certain properties taken by the values of the output parameter are specified.

- The procedure (algorithm) by which the computational model of the RDS may actually be accomplished is specified.

In essence, at this level, it is described how the computational model, described at the upper level (computational level), is implemented, i.e., this is the level of how the RDS is implemented. In particular, the representation of the input and output datasets and the description of the operations defined over them are specified.

The specification of the extensional and intensional information of the input/output datasets guarantees that: (i) the algorithm can execute on the provided input dataset; and (ii) the requester can accept the delivered output dataset with respect to their syntactic types.

At implementational level:

- A RDS is a software, with a discoverable and invocable interface. A service interface enabling users to invoke the RDS using standard protocols is specified.

- An Institutional Commitment on the RDS, in the form of a Service-Level Agreement (SLA), is specified; in the Service-Level Agreement (see below) the non-functional aspects of the RDS, mainly related to the Quality of Service (QoS )provided by the RDS, are specified.

- The software deployment, including scalability and fault tolerance issues (in the case that the RDS provision model is “as-a-software” – see below), is described.

At this level, an RDS is a software developed by applying software engineering practices on the algorithm described at the upper level. It delivers value to researchers by facilitating outcomes they want to achieve without the ownership of specific costs and risks.

The relationship between the three levels has the property of multiple realizability (one-to-many relationship), i.e., for any computational description of a particular RDS there may be several algorithms for executing that computation, and any algorithm may be implemented in several ways.

2.4. Research Data Service Profile/Metadata

The main purpose of RDS profile/metadata is to facilitate the service discovery and use. Metadata assists in service discovery by allowing services to be found by means of relevant criteria. In addition, it allows to bring similar services together, distinguish dissimilar services, and give location information. The RDS profile/metadata definitions should be structured at multiple levels in order to reflect the layered structure of the RDS description. In particular, they have to describe: (i) the semantics of the input/output datasets; (ii) the semantics of the operations over them; (iii) the non-functional aspects of RDS; and (iv) information about the provider of the service.

2.5. Type of Research Data Service

By type of a RDS is intended a named group of RDSs that have a similar computational model (functionality) but can have different implementations.

2.6. Research Data Service Classification

This is the act of assigning a category, or more than one category, to an RDS, since there might be several disjoint classifications; moreover, an RDS might be used for several purposes. Classification is used to ensure a more effective and efficient retrieval of the sought data service. Data Service classification is very much domain-specific.

For example, INSPIRE defined a “Classification of Spatial Data Services” as part of the European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1205/2008.

Concluding this paragraph on the Description of RDS, we like to highlight some additional characteristics of RDSs:

- They are, in general, stateless.

- Their course of action affects only the input dataset.

- They are a specialization of Web services. Indeed, although all Web services use data, they are essentially a programmatic layer on top of distributed systems, while RDSs serve as “fronts” for data and are based on a richer model of that data [].

- In contrast to traditional Web services, RDSs need to be model-driven.

- They are, according to the definition given in this paragraph, essentially “research dataset transformation services”.

- They may or may not be implemented as a Web service.

- They are applicable in scenarios implementing some part of a research process.

- They are a subclass of service in a general sense.

We also give an informal definition of RDS (actually, of Research Software) extracted from []:

“software that is developed within academia and used for the purposes of research: to generate, process and analyze results. This includes a broad range of software, from highly developed packages with significant user bases to short (ten of lines of code) programs written by researchers for their own use”.

2.7. Research Data Service Provision Models

A Provision model describes the modality with which a research data service is provided. The following two provision models are envisaged:

- “as-a-Service”: such modality implies that the RDS is hosted, operated, and delivered over the Internet by the service provider.

- “as-a-software”: such modality implies that the RDS is a software entity that is maintained by a service provider and can be invoked and deployed in the user computational environment before being actually used.

Currently, there is a growing interest toward a hosted-services world. This trend is evidenced by the number of contexts within which RDSs have been utilized in recent years: service-oriented architectures (SOA), “as-a-service”, and most recently, cloud computing. However, increasingly, the volumes of data produced by high-throughput instruments and simulations are so large that it is much more economical to move computation to the data rather than moving the data to the computation, i.e., the “as-a-software” provision modality of the data service is more appropriate. In this case, the RDS deployment must be compatible with the target computational environment.

2.8. The Main Actors in the RDS Discovery and Use Process

The following actors are envisaged:

- RDS Provider: A person or authority who commits to have the service executed.

- RDS Producer: A person or organization that actually performs the actions constituting the delivery of the service.

- RDS Customer: One that requests the data service and then negotiates for its customized delivery.

- RDS Consumer: A person who is the direct beneficiary of the service.

- RDS Provider and RDS Producer may coincide, but this is not always the case.

- RDS Customer and RDS Consumer may coincide, but not necessarily.

- RDS Consumer and RDS Producer may also coincide, in very particular situations.

2.9. Service-Level Agreement (SLA)

A Service-Level Agreement is an agreement between an RDS Provider and an RDS Customer that details the nature, quality, and scope of the service to be provided, i.e., what services the provider will furnish and which performance standards the provider is obligated to meet. An SLA can be a legally binding formal or an informal “contract”.

2.10. Composite Research Data Service

This is an RDS that results from the composition of several research data services for the purpose of carrying out a complex research task. In essence, it is a chain of single data services. Three types of service chains are distinguished in (ISO/TC-211 2002):

- User-defined chaining: the user manually composes the service chain.

- Workflow-managed chaining: a pre-defined service chain is executed and controlled by a workflow service.

- Opaque chaining: the service chain appears to the user as a single service.

2.11. Scientific Workflow

This is a precise description of a scientific multi-step process in order to coordinate multiple tasks. Each task represents the execution of a computational process. Scientific workflows orchestrate RDSs so that they cooperate to efficiently perform a scientific application.

2.12. Research Data Service Registration

By RDS registration capability we mean a capability enabling researchers to make RDSs citable as a unique piece of work. RDSs should be assigned a “Digital Service Identifier” (DSI) by a Registration Agency. A DSI is a unique name within a scientific domain and provides for persistent and actionable identification of RDSs. The data service registration capability should include a specified numbering syntax, a resolution service, a metadata model, and an implementation mechanism determined by policies and procedures for the governance and application of DSIs.

2.13. Domain-Specific Research Data Service Catalogue/Registry/Directory

RDS catalogues1 /registries/directories are used to publish registered RDSs. They are called to:

- Contain an organized and curated collection of domain-specific RDS descriptions (service metadata and DSI).

- Categorize RDSs according to their type.

- Clearly state how each RDS is delivered.

- Constitute a means of centralizing domain-specific descriptions of RDSs that are available on the Internet.

- Support search of RDSs that provide a set of requested functionalities.

- Act as a knowledge management tool allowing researchers to route their requests for and about RDSs to appropriate service providers who own, are accountable for, and operate them.

In essence, RDS catalogues implement a function of service indexation.

2.14. Research Data Service Publication/Advertisement

By RDS publication/advertisement is intended a process that allows the research community to discover and make assertions about the suitability of a RDS to fulfil a research need. The ultimate aim of RDS publication/advertisement is to make RDSs available for reuse both within the original disciplines and the wider community.

In addition, it should allow, for those who create data and develop data services, to receive academic credit for their work.

The service publication/advertisement process is a two-step process: first, the service is registered, i.e., it is endowed with a DSI; then, the DSI together with the RDS metadata are stored in a publicly accessible data service registry/catalogue/directory.

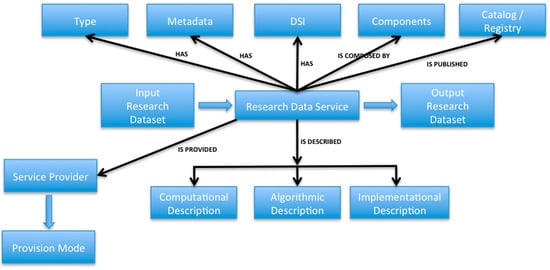

Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of the main characteristics of an RDS.

Figure 2.

RDS (Research Data Service) Main Concepts.

3. Research Data Service in Context

The research ecosystem is composed of:

- Research teams distributed worldwide;

- Research data produced, collected, and/or observed by researchers and distributed worldwide; and

- RDSs developed by researchers and distributed worldwide.

These components of the research ecosystem are networked through the Internet. In such a networked scientific environment, a challenge faced by researchers is to be able to pinpoint the location of research data and data services that fulfil their research needs. An emerging “best practice” in the scientific method is the process of publishing research data and data services. The data publication takes place in domain-specific Data Centers or (Institutional) Repositories [], while the publication of RDSs takes place in domain-specific Registries. Publishing research data and services implies that both are endowed with identifiers and metadata. Often, data/service understandability and accessibility is enforced by the use of domain-specific ontologies, taxonomies, and/or classifications.

Several types of RDSs can be distinguished, e.g., services that acquire data, curate data, store data, access data, retrieve data, move data, discover data, preserve data, analyze data, visualize data, transform data. Some of these RDSs (for example, data curation, data storage, data preservation) are used by professionals, i.e., database administrators and data curators. Some others (for example, data access, data retrieval) are facilities offered by the systems that contain the data, i.e., database systems, and are used by generic users and researchers. Lastly, some others, i.e., data processing services, implement algorithms developed by data scientists that analyze, visualize, and transform research datasets for the purpose of gaining insight into complicated issues. In the context of this paper, by RDS we consider only this last category.

All RDSs have a few things in common []:

- They are information providing services. This means that there is no “real world” counterpart to the computation performed. The execution of the service does not affect the real world but only the information space in which the service is executed.

- After the RDS execution, either a new fact becomes known or a known fact is updated.

A research data software in order to become a service requires a commitment on behalf of the service provider, be it a public institution or a private organization. The commitment can take the form of a Service-Level Agreement (SLA). However, in the scientific context, this is not always the case. An RDS can be provided also by an individual and not just by an institution or organization. In this case, often the service is offered for free. In such a case, a simplified version of the SLA can be used.

Some criteria for the selection of the service provider must be established, for example:

- Do we trust the provider?

- How reliable is the provider with respect to her/his promises?

- Does the provider comply with security standards and has been security-assessed?

As stated in the previous section, there are two ways of delivering RDSs: (i) the service, invoked by the user, runs in the service provider’s premises (“as-a- service”); (ii) the service is transported in the user premises, and downloaded in the local platform (“as-a-software”).

An example of the first way of delivering services is the cloud computing level of service provision “Software as a Service (SaaS)”; in this case, clouds deliver special-purpose software that is remotely accessible by consumers through the Internet with a usage-based pricing model.

The second way of data service delivery is made possible through service-oriented architectures (SOA) that encapsulate computation into transportable compute objects that can be run on computers that store targeted data. SOA compute objects function like applications that are temporarily installed on a remote computer, perform an operation, and then are uninstalled.

From an organizational point of view, moving data services to data stores calls for the creation of service stations (science data centers).

An RDS can be the result of a composition of individual RDSs. The composability of RDSs is of great value as it enables more complex data services. However, in order to create a composite RDS, the single components must be composable. Indeed, some inconsistencies between the descriptions of two services to be composed may arise. When these inconsistencies are resolved, the two services are composable.

In ISO terminology, the new complex service is called “service chain”, which is defined as a sequence of services where, for each adjacent pair of services, occurrence of the first action is necessary for the occurrence of the second action. A service chain consists of several services, each of which constitutes one part of the overall functionality. During service composition, a number of services have to be discovered which, altogether, provide the required functionality. Service discovery is, hence, a very important part of service composition.

At present, RDSs are generally isolated applications. Nevertheless, several services may be composed to create a new service.

Science becomes increasingly reliant on the analysis of massive datasets and the use of distributed data services. The workflow programming paradigm is seen as a means of managing the complexity in defining a complex scientific procedure.

The workflow systems constitute an efficient technology for creating and running composite RDSs.

A further consideration to be kept in mind when addressing the RDS discoverability problem is the tight connection between research data and services.

RDSs are domain-specific. Of course, there are a few (e.g. Fourier transform, string matching) that are quite general and could somehow be discovered by their functionality/type, but these are rather few, and even when one does use them, they are often tailored for a specific domain. For example, the Fourier transform will often be set up to accommodate the kind of boundary conditions one finds in plasma physics; the string matching program will be tuned for genetic search; and so on.

In essence, there is not much point in separating the RDS from the domain of research data it operates on. Useful RDSs are nearly always domain-specific, and therefore finding them could be linked to the problem of finding the data.

In other words, whatever ontologies, schemas, or metadata are used for describing data could also be used for describing RDSs.

4. The Research Data Service Discovery Process

The mission of the RDS discovery process is to seek an appropriate RDS for a service requester on the basis of the service descriptions in-service advertisements and the requester’s requirements. It enables researchers to locate the most suitable RDSs for their scientific inquiry among a large number of published services. Effectively locating relevant RDSs and efficiently performing the discovery operation in a scalable way is what is required in order to enable researchers to efficiently conduct their research activities.

A typical data service discovery scenario is the following:

A researcher has produced or has access to a specific type of research dataset on which she/he wants to apply an algorithm with a precise functionality in order to conduct a research activity. Therefore, she/he has to search in the network to find a data service that provides the needed functionality, and it can operate on the type of dataset in her/his possession with QoS and costs acceptable by her/him. In the case that the service is provided in the “as-a-software” modality, the software deployment should be compatible with the hosting computational environment.

The RDS discovery process is enabled by:

- The RDS description.

- The RDS publication.

- The RDS matchmakers.

The RDS description is a major pre-requisite or enabler of the RDS discovery process. As the publication of the service relies on extended service descriptions going beyond a mere specification of the service interface, the RDS description is a pre-requisite of the RDS publication. In turn, the publication is an essential pre-requisite of the RDS discovery. If a service is not published, it cannot be actually discovered and used. In this case, the only way the service can be discovered would be its unique identifier that could be circulated via friend-of-a-friend schemes. Such an identifier should map to a location from which more information about the service can be retrieved.

The RDS matchmakers are programs designed to implement the task of RDS discovery based on the service functionality.

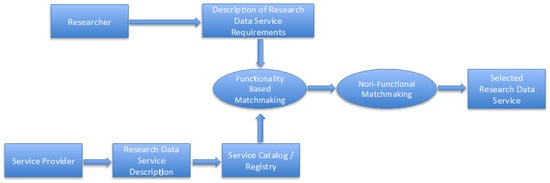

RDS discovery is a process that includes the following steps (cf. Figure 3):

- First, the service requester submits a query to an RDS registry in order to locate an RDS suitable for her/his research needs.

- Second, a functionality-based matchmaking is performed to discover those services that functionally match the service requester requirements.

- Third, in case of a match, non-functional matchmaking is employed in order to filter the matches according to the service requester’s non-functional requirements (QoS, availability, security, reliability, privacy, pricing).

- Finally, if there are still results retained after the filtering, these results are ranked according to preferences given by the user to respective non-functional terms.

Figure 3.

Research Data Service Discovery Process.

The first step requires a language to express the functionality of the service. The second step requires the specification of a matching algorithm between service advertisements and service requests that recognizes when a request matches an advertisement. The RDS selection, i.e., the last two steps of the discovery process, is almost as important as the service discovery. After discovering RDSs whose functionality match the functionality of the requirement, the next step is to select the most suitable service. Each service can have a different quality aspect and hence service selection involves locating the service that provides the best quality criteria match.

In the RDS discovery scenario, the tasks of the three actors of the discovery process, service consumer, service provider, and service catalogue, are the following:

The service consumer must be able to precisely describe:

- The service functionality.

- The intensional and extensional information about the dataset in her/his possession (input dataset) as well as this type of information about the expected output dataset.

- The pre- and post-conditions.

- The computational environment that will host the data service (in the case of “as-a-software” modality).

The service provider must be able to advertise an RDS in service registries by precisely specifying:

- The RDS profile/metadata.

- A Service-Level Agreement.

The RDS catalogues must handle service discovery requests by identifying suitable RDSs matching the requests.

These three actors have to collaborate in RDS discovery.

The RDS discovery process can be either fully automatic or manual. This means that both humans (researchers) as well as automated programs or agents acting on behalf of researchers can be considered as service requesters. A fully automatic RDS discovery process involves a service consumer (researcher), a service provider, a search agent, and a reasoning support.

A problem can arise when the requester is not able to formally specify the service functionality. This could depend on the fact that she/he is not an expert in semantic formalisms and ontologies and does not know how to describe her/his requirements. In this case, a different approach in the specification of the functionality of a RDS must be followed. For example, the requester could be guided to specify her/his requirements by an appropriate interface, i.e., a question–answering interface, provided by the service catalogue/registry.

The RDS discovery is initiated by users/agents by invoking the Application Programming Interface (API) or exploiting the graphical User Interface (UI) of a service registry. Once the researcher has selected the most appropriate RDS, she/he has to invoke it using standard protocols.

5. RDS Discovery: Enabling Technologies

In this section, the main technologies that enable the RDS discovery are concisely described: (i) the knowledge representation languages designed for describing RDSs (cf. Section 5.1); (ii) the semantic RDS matchmaking, i.e., programs designed to implement the task of semantic RDS discovery (cf. Section 5.2); (iii) the RDS metadata models, i.e., the descriptive information about a RDS that enables metadata-based RDS discovery (cf. Section 5.3); (iv) the mediation, i.e., a technology that enables the overcoming of data heterogeneities and functional inconsistencies (cf. Section 5.4); (v) domain-specific ontologies that provide the semantic underpinning for RDS discovery (cf. Section 5.5); (vi) the RDS identification that makes an RDS citable (cf. Section 5.6); and (vii) the data service catalogues that enable data service providers to publish their RDSs (cf. Section 5.7).

5.1. Knowledge Representation Languages

Various languages for the formal and machine-comprehensive representation of conceptual models have been developed. In this section, we focus on formal models of the semantics of services offered over the Web via a well-defined interface (Web services) and the knowledge representation languages that have been designed for describing services using these models. Those models, languages, and their accompanying mechanisms for the matching of service offers and request descriptions have been investigated by the Semantic Web Service community since the early 2000s and are promising candidates for describing RDSs in order to enable their effective and efficient discovery.

Semantic service models typically specify what a service does by means of a service profile. Such a profile can comprise a semantic specification of the input and output of a service, a description of its preconditions and effects, and a declaration of non-functional service properties such as availability or pricing. Semantic process models specify how a service achieves a certain functionality, e.g., by making the internal data and control flow explicit. Given a certain input and given that the stated preconditions (assumptions about the state of the world before service execution) hold, a successful service invocation results in a certain output and a certain effect (the state of the world after execution).

Prominent representatives of this class of approaches are OWL-S (Web Ontology Language for Web Services) [] and WSMO (Web Service Modeling Ontology). OWL-S is an upper-level ontology describing the semantics of services. It is based on W3C Semantic Web Standards like OWL (Web Ontology Language) []. The WSMO framework specifies a conceptual model of service semantics, the Web Service Modelling Ontology [], and the formal language WSML (Web Service Modeling Language) [] for the semantic description of services based on this model. With WSMO-Lite [], a lightweight variant of WSMO, which is compliant to any ontology language with an RDF syntax [], has been developed. In contrast to these top-down approaches to service modeling, the W3C recommendation, SAWSDL (Semantic Annotations for WSDL and XML Schema) [], provides means for annotating WSDL [] components by referencing concepts from semantic service models. SAWSDL does not specify a semantic service model nor does it make any assumptions on such a model or its underlying (ontology) representation language. Together with microformats for service annotation, such as hRESTS [], SA-REST (Semantic Annotation of Web Resources) [], and MicroWSMO [], this allows for modeling service semantics in a bottom-up manner, i.e., adding pieces of semantics on an if-needed basis, and in compliance with W3C standards.

Along similar lines go recent efforts on Schema.org2, which provide the vocabulary needed to describe services (called Actions) that can be executed. First efforts have been made to automatically link objects to the actions that may be performed on them via the potentialAction property (see e.g. []).

In addition to this, there have been efforts to unify existing service models into a minimal model and expose service descriptions in RDF. This makes service descriptions query-able, like "ordinary" linked data using SPARQL [,]. For a comprehensive discussion of existing service description approaches, see also e.g. [,,].

Finally, existing service models and annotation mechanisms could potentially be adopted and/or adapted for the description of RDSs.

5.2. Reasoning/Matchmaking Support

Service matching is the process of comparing the description of a requested service functionality (service request) with the descriptions of advertised services. The result is a list of service offers ranked by their matching degree (the degree of suitability for the considered request).

Existing service matchmaking and selection approaches differ with respect to:

- The supported service description language(s) and underlying service model(s).

- The way service matchmaking is accomplished.

- The parts of the service semantics that are considered.

- Whether service composition is supported or not.

There are also differences regarding:

- Scalability and retrieval performance in terms of correctness and response time.

- The type of service search which is supported.

- Whether user preferences are considered or not.

- Whether a matchmaker can deal with incomplete or inaccurate information.

While the majority of approaches for semantic service matchmaking are designed for a specific type of service description, (e.g. OWL-S- [,] or WSML-based []), some can deal with different formats []. With regard to the techniques used for determining a matching degree, Klusch [] distinguishes between logic-based matchmakers, non-logic-based and hybrid matchmakers. Logic-based approaches compute a matching degree using logical reasoning on service descriptions. Typical matching degrees are exact, plugin, or subsumes. Non-logic-based matchmakers apply text similarity measures or graph matching techniques to determine a matching degree (e.g. []). Hybrid matchmakers combine several matchmaking techniques and aggregate their results []. They often employ learning techniques to optimize their aggregation strategy. According to Klusch [], matchmaking can consider a service's profile or its process model. Profile matching may be based on functional or non-functional service properties such as QoS, or both. Functional matchmaking might take inputs and outputs, preconditions and effects, or both, into account. Based on the results of the S3 Contest, a comparative evaluation of the performance of semantic service matchmakers [], Klusch concludes that most of the matchmaking approaches consider input and output only; just a few matchmakers take preconditions and effects into account. Hybrid matchmaking seems to produce results of higher precision. Matching both input and output and preconditions and effects comes, however, at the price of higher response times. While most of the approaches to Semantic Web Service selection are designed for the largely automatic retrieval of services, there are also solutions that support an interactive and incremental style, which involves humans in the selection process (e.g. [,]). The latter account for the fact that service requirements are often incomplete or inaccurate at the time a service is searched for. Human users would rather construct their requirements when being faced with available choices in terms of service alternatives and their characteristics []. This requires means to deal with uncertain service requests and offers. Approaches that model and consider user preferences during service matchmaking and ranking are particularly helpful to rank advertised services in scenarios where the number of matching service offers is potentially high (e.g. [,]). There are also solutions for service selection that can handle the opposite case, where no matching service offers can be found. For instance, query relaxation techniques can be applied in those situations to identify service offers that do not exactly fit a certain request, but might be an appropriate alternative [].

5.3. Research Data Service Metadata/Profile

The RDS metadata/profile is the descriptive information about the functionality that a RDS wants to provide to a research community. Each published RDS must be endowed with metadata information. The main purpose of the RDS metadata/profile is to enable service discovery. In metadata-based RDS discovery, the RDS metadata/profile is matched against the requirements in order to find an RDS that better meets the user needs. The service metadata/profile also helps potential users know what is in the services, who created them, and what usage restrictions they might carry.

At present, formal metadata/profile models for RDSs are missing. There are no metadata/profile models for describing, e.g., the functionality provided by a data mining tool, a data visualization tool, a data analysis tool, etc.

As already said, the RDS profile/metadata definitions should be structured at multiple levels in order to reflect the layered structure of the RDS description. In particular, the RDS metadata/profile should be described at the following levels []:

- At the data semantics level, the semantics of the input/output datasets is described; their logical structure (schema) is described as well as the relationship between them. If a standard data model (e.g., the relational model) is considered, the relational schema is appropriate; otherwise, descriptions of standard domain-specific data formats should be used.

- At the operation semantics level, the semantics of the data operations of the RDS is described. This description must be expressed by using appropriate knowledge representation languages based on domain-specific ontologies.

- At the execution semantics level, the non-functional aspects of the RDS are described. This demands management of QoS metrics for RDS. RDSs in different domains can have different quality aspects. QoS metrics need shared semantics for interpreting them as intended by the service provider. This can be achieved by having an ontology that defines domain-specific QoS metrics. The non-functional aspects of an RDS could also be included in a kind of standardized contract (Service-Level Agreement) between the service provider and the potential consumers that specifies specific and measurable aspects related to the service offerings. Appropriate languages, like the WSLA, can be used to specify the SLAs.

- At the operational semantics level, the computational environment where the RDS can run must be described using a shared ontology (in the case where the RDS is delivered with the “as-a-software” modality).

The first two levels, essentially, describe the semantics of the RDS description at the computational and algorithmic levels, while the last two levels describe the semantics of its description at the implementational level. This layered RDS metadata/profile description allows a more precise description of the input/output datasets, the data operations and the non-functional aspects of the RDS. The RDS metadata descriptions are stored in domain-specific catalogues.

Finally, we stress the fact that the quality of data service metadata/profile is the most important factor for an effective and efficient RDS discovery.

Valuable examples of existing metadata models for data service are ISO 19119 and W3C WS-MetadataExchange. The INSPIRE Directive builds on ISO 19119 to specify how to describe shared data services, enabling their cataloguing and discovery. The Directive defined a set of well-known spatial data service types.

Additionally, we present the structure of the Service metadata adopted by the Biodiversity Catalogue (cf. Table 1).

Table 1.

Biodiversity Catalogue Service Metadata.

5.4. Mediation Support

In the RDS discovery process, several kinds of heterogeneity and logical inconsistencies can arise that must be overcome in order to successfully carry out this process.

The first kind of heterogeneity can arise between the dataset in possession of the researcher and the dataset on which a given data service can act, in the case that different data models are adopted to represent these two datasets. By resolving this kind of heterogeneity we say that a structural exchangeability between the two datasets has been achieved.

A second kind of heterogeneity can arise between the “semantic universe of discourse” of the two datasets (differences in granularity, differences in scope, temporal differences, synonyms, homonyms, etc.). By resolving this kind of heterogeneity, we say that a semantic exchangeability between the two datasets has been achieved.

Structural and semantic exchangeability guarantee that the two datasets are exchangeable, i.e., it is possible to transform the researcher’s dataset structured under a schema into a dataset (the dataset on which the data service can operate) structured under another schema. The exchangeability between the two datasets enables the data service to act on the researcher’s dataset.

A logical inconsistency problem can arise at the functional level when the functionality provided by a service provider does not precisely match with the one requested by a user. In this case, some inconsistencies arise between the logical relationships of the two descriptions expressed in some logic-based languages: the one that describes the functionality offered by a published data service and the other that describes a service need of a researcher. This means that the logical relationships between the two functionality descriptions do not share a logical framework. In this case, we have functional inconsistency between two service descriptions. When these inconsistencies are resolved we say that the two services are compatible, i.e., the published service is suitable for satisfying the user service need.

The main concept that enables the overcoming of data heterogeneities and functional inconsistencies is mediation []. We can distinguish two levels of mediation:

- Mediation of data structures that permits data to be exchanged according to structural and semantic matching.

- Mediation of functionalities that makeit possible to overcome logical inconsistencies between representations of service functionality.

Automated intermediary services heavily rely on adequate modeling of both the exchanged information and the user needs. In essence, the intermediary services must translate languages, data structures, logical representations, and concepts between two systems. The effectiveness, efficiency, and computational complexity of the intermediary service very much depend on the characteristics of the information models (expressiveness, levels of abstraction, semantic completeness, reasoning mechanisms, etc.) and languages adopted by the server provider–researcher entities.

Intermediary services are implemented by mediators, sometimes also called brokers. They are software modules that exploit encoded knowledge about certain sets or subsets of data, data services and user needs in order to implement an intermediary service.

Ontologies have also been extensively used to support intermediary functions because they provide an explicit and machine-understandable conceptualization of a domain.

It is worthwhile to mention that some international programs have adopted mediation-based approaches for data and service discovery and access, including GEOSS (Global Earth Observation System of Systems) [], US NSF Earth Cube [], and ICSU WDS [].

5.5. Domain-Specific Ontologies

Ontologies constitute a key technology enabling a wide range of research data services. They provide the semantic underpinning that enables data access, discoverability, understandability, usability, RDS discovery, and the implementation of intermediary services.

Ontologies were initially developed by the Artificial Intelligence community to facilitate knowledge sharing and reuse. An ontology consists of a set of concepts, axioms, and relationships. It constitutes an explicit specification of a conceptualization of a domain of interest, i.e., an abstract view of the objects, concepts, and other entities that are assumed to exist in a domain of interest and the relationships that hold among them []. The abstract view of a domain of interest can be represented by a declarative formalism and the set of objects that can be represented is called the domain of discourse.

A community of practice has to establish its own domain of discourse and choose a formalism, i.e., a knowledge representation language, in order to create its own domain-specific ontology. In addition, a set of linguistic terms by which the members of the community will refer to these objects must be identified. Building this set of terms is difficult because words often have multiple synonyms and because the meanings of words in natural language always depend heavily on the contexts in which the words are used. To overcome this difficulty, explicit lexicons should be created which offer the members of a community of practice a set of terms with which to refer to specific concepts. Another difficulty in creating a domain-specific ontology involves the ability to identify an appropriate level of abstraction at which to view the objects, concepts, and relationships in a domain. Several domain-specific ontologies are being developed (e.g., Gene Ontology, Sequence Ontology, Cell Type Ontology, Biomedical Ontology, CIDOC).

The relationship between data in domain-specific data collections and instances of objects and concepts in a domain-specific ontology is expressed by means of mappings. On top of the data layer of the data collection(s) of a scientific domain, a conceptual view of data, expressed in terms of an ontology, should be created []. As data layer and conceptual view are at different levels of abstraction, they are expressed in terms of different formalisms. For example, while logical languages are nowadays used to specify the ontology, the data layer is usually expressed in terms of the relational data model. Specific mechanisms for mapping the data in the collections to the elements of the ontology should be developed.

The main reason to build an ontology-based conceptual view of a data collection is to improve data intelligibility and, thus, usability, as well as to provide high-level services to the clients of the system that manages that collection.

In the context of a networked scientific world, domain-specific ontologies are not standalone artifacts. They relate to each other in ways that might affect their meaning, and are inherently distributed in a network of interlinked semantic resources, taking into account, in particular, their dynamics, modularity, and contextual dependencies. The alignment of domain-specific ontologies is crucial for research data service discovery. It is achieved through a set of mapping rules that specify a correspondence between various entities, such as objects, concepts, relations, and instances. Several concept and relation constructors are offered to construct complex expressions to be used in mappings.

The role of ontologies in the RDS discovery is very important as they allow ontological descriptions of the functionality provided by an RDS. The use of ontologies to describe the semantics of the operations of an RDS makes them machine-interpretable, allows the users to pose concise and expressive queries, and supports a logical reasoning in order to discover a relationship between user queries and service descriptions in RDS registries.

A “functional ontology” must be used in order to specify the functionality of an RDS. In functional ontologies, each concept represents a well-defined functionality. The intended functionality of each service can be represented as annotations using this ontology. If an RDS is annotated using a functional ontology, the service discovery algorithms can exploit these annotations for a better search result set. The functional ontology is different from the typical ontology.

To effectively perform discovery of RDS, the semantics of the input/output datasets has to be taken into account. Hence, if the data involved in RDS operation is annotated using an ontology, then the added data semantics can be used in matching the semantics of the input/output dataset of the requirements. The ontology used to represent data semantics is a typical ontology. These ontologies can be replaced with standard vocabularies, taxonomies, etc.

The ontologies used for making the semantics of RDSs explicit can be organized in two ways:

- Multiple ontology approach: each service or query is described by its own ontology. It cannot be assumed that several local ontologies share the same vocabulary. In this case, the alignment of the local ontologies with the ontology used to annotate a published RDS is of crucial importance.

- Single ontology approach: a global ontology is used, which provides a shared vocabulary for specifying the semantics of all services and queries. Such an approach can be adopted when all service descriptions in the catalogue have been created with a view on a scientific domain that is shared by all the requesters. Such a common ontology is called domain ontology.

In conclusion, we can affirm that two background ontologies are necessary to support the RDS discovery process: one that formally defines the possible data types of the RDS’s arguments and one that formally describes the possible operations performed by RDSs. The RDS provider and requester use terms from these ontologies in order to specify what types the arguments have, what operation is performed on them, and how the input parameters relate to the output parameters.

5.6. Digital Service Identifier (DSI)

The identification and citation of an RDS is of paramount importance in the scientific field for the following reasons:

- Discoverability: endowing a research data service with an identifier provides an actionable, interoperable, and persistent link to this service that makes the service discovery much easier.

- Reusability: reusing an RDS instead of replicating it has two main advantages: (i) it allows researchers to invest more time into research and avoid wasting time by replicating software that already exists; and (ii) it permits to save a significant amount of resources, as software is expensive to develop, which could then be invested into new research.

- Reproducibility: it is very important, in order to reproduce a research result, to know the exact version of the RDS used to generate it; therefore, there is a need for making a data service identifiable.

- Credit attribution: each RDS should be recognized as a valuable research object. Therefore, it should become a citable scientific deliverable of equivalent value to researchers as that of a publication. Software citation would allow researchers to gain credit for developing software; after all, most research data services are developed by researchers. When a researcher publishes a scientific result generated by using someone else’s data service it could be a good practice to cite it in the publication. It is also important that publishers recognize the need to cite research data services as a vital part of the publication process.

Unfortunately, currently, methods for RDS citation are missing. A similar problem has been with data, where identifiers such as Handles, DOIs, URNs, and other identifiers are used to provide an actionable, interoperable, and persistent link to a specific dataset. The same system could be used to identify software.

A Digital Service Identifier (DSI) should contain, at a minimum, the following components (although practices could vary from field to field):

- The developer of the RDS.

- The date the RDS was published.

- The name of the RDS.

- A unique global identifier, which is a short name or character string, guaranteed to be unique among such names, which permanently identifies the RDS, independent of its location. The unique identifier should resolve to a page containing the functional and non-functional description of the data service (data service metadata). This data service metadata should include a link to the actual RDS.

5.7. Data Service Catalogues

RDS catalogues enable data service providers to publish their RDSs. They contain a curated collection of domain-specific RDS descriptions. They constitute a means of centralizing domain-specific data descriptions of services that are highly distributed. The main mission of the RDS Catalogues is to facilitate RDS discoverability. To this end, they define standard methods for publishing, discovering, and managing information about RDS providers, RDSs, and the technical interfaces of RDSs. Registries are the dominating technological basis for RDS publishing and discovery. In essence, they act as knowledge management tools, allowing researchers to route their requests for and about data services to the service providers who own, are accountable for, and operate them. They allow researchers to query RDS descriptions, select an RDS, and invoke it, regardless of where it exists in the scientific world.

To efficiently support RDS discovery, catalogues should include the following elements for each RDS:

- A description of the RDS.

- An identifier of the RDS (DSI).

Data and information that help service providers set expectations for their service requestors (Service-Level Agreement).

- Who is entitled to request the RDS.

- The cost of the RDS (if any).

- How to request the RDS.

- How the service delivery is fulfilled (RDS provision model).

- Service categorization or type that allows it to be grouped with other similar services.

RDS catalogues, in order to efficiently and effectively achieve their mission, should:

- Adopt a formal registration process that allows RDSs to be properly registered in the registry.

- Adopt a generic model to store all the information.

- Support specifications of services and/or ontology-based annotations used to enrich the service specifications. Mechanisms that enable the enrichment of service specifications with ontological annotations can include user input (either guided or based on a specific ontology of his/her choice), semi-automatic annotation (the registry proposes the ontology concept that matches service functionality), as well as automatic semantic annotation (the catalogue alone performs the atomic annotation and selects the best possible match from the alternative ones).

- Encompass smart algorithms which efficiently organize the service advertisement space. In the case of a functionality-based discovery process, the service space is organized according to domain-specific concepts. The discovery process relies on the subsumption relationships between these concepts in order to infer the exact semantic relationship between a service request and a service (functional) advertisement. In the case that the discovery process is based on a service non-functional specification, different approaches have been proposed which rely either on the limits that are posed on quality terms or on relationships between the different non-functional service advertisements [,].

- Provide meaningful results to the user even if there are no perfect matches to the user query. Concerning functionality-based service discovery, an interesting categorisation of service matches has been proposed [] encompassing five main categories, going from the most accurate to the less accurate one. Concerning non-functional service discovery, four main service result categories have been proposed []: (i) super: the non-functional service offer promises even better results than those expected by the non-functional service demand/request (e.g., better availability values); (ii) exact: the service offers exhibit the same or a more strict service level than the one expected by the service request; (iii) partial: the service offers solutions that partially satisfy the service request. This means that some quality term constraints of the service request are respected but others are not; and (iv) failed: the service supplies solutions that are totally unacceptable by the service request, meaning that each quality term constraint in the service request is not satisfied/respected.

- Rank the service discovery results according to specific criteria that can include non-functional quality terms (e.g., response time and cost). Such a ranking can really assist the user in selecting the most appropriate service but requires that user preferences are already in place, thus either collected from the user or derived and stored in its user profile.

- Be scalable to handle the publication and discovery of a high number of services. In this respect, decentralised and peer-to peer architectures are advocated in order to also overcome the single point of failure issue. In such decentralized architectures, there should be mechanisms that partition the service advertisement space accordingly by also allowing for some degree of replication for fault-tolerance reasons.

- Be robust enough to deal with change. Different types of changes might occur: (i) the semantic (functional) specification of the service is modified; (ii) the non-functional specification of the service is modified; and (iii) domain ontologies are evolved.

- Be able to monitor the status of the RDS specifications in order to keep them updated. There can be two main approaches that can be followed, either alternatively or in combination: (a) the service providers are responsible for updating the specification of their services; (b) the service catalogue constantly looks for changes in the functional and non-functional RDS specification and applies them. However, this approach is certainly harder than the previous one.

- Allow that service specifications can be specified in different languages and different (domain) ontologies may be used. Language and ontology heterogeneity can be overcome by adopting mediation techniques (see subsection 5.3).

- Support, when functional service discovery fails (i.e., no single service can satisfy the user request), service composition, i.e., a combination of data services that can still satisfy the functional requirements of the user. Different approaches can be used for service composition, e.g., AI-based approaches, graph-based approaches, etc.

- Support data service advertisement. This means that RDS catalogues proactively send to potential users information about newly published RDSs, changes in data service specifications, etc.

- Provide visual facilities which will guide the users in order to provide for their requirements. Indeed, we have assumed that service discovery relies on ontology-based languages to express service requirements, but it is not certain that such languages can be exploited by users as they might not possess the needed expertise and skills. We cannot also expect that agents are employed by scientists to interact with the registry and obtain the respective discovery results.

- Adopt strong stewardship and security controls.

- Finally, provide the description of platforms and infrastructures which can provide support to the execution and provisioning of RDSs. Infrastructure services can include well-known cloud computing and grid computing services, which provide the respective resources to support the software provisioning. Such services can be essential in case of a software that has to be deployed somewhere and run as a service but the scientist/researcher does not have the resources to support this deployment. Before discovering and using infrastructural services, they have to be described in an appropriate manner. While they seem to share common characteristics, the semantics can be sometimes different while also there are some characteristics that are more suitable for one type over the other. In this sense, the catalogue/registry should have the capability to cope with this type of heterogeneity.

A catalogue is an authoritative, centrally controlled store of information []. A lightweight version of a catalogue is the centralized service of indexes. An index is a compilation or guide to information that exists elsewhere. It is not authoritative and does not centrally control the information that it references.

The key difference between the two approaches is not just the difference between a catalogue itself and an index. The key difference is one of control. Who controls what and how do RDS descriptions get discovered? In the catalogue model, it is the owner of the catalogue who exercises this control. In the index model, since anyone can create an index, the research communities or the market determine which indexes become popular.

Here, below, we briefly describe some notable examples of service Catalogues.

The Universal Description, Discovery and Integration (UDDI)3 is an XML-based registry for registering and locating Web service applications. The UDDI specification defines a standard method for publishing, discovering, and managing information about Web service providers, Web services, and the technical interfaces of Web services. In a UDDI registry, a data model is used to describe the business function and provider of the service, the technical details of the service (including a reference to the interface of the service), various attributes or metadata, such as taxonomies, transports, digital signatures, and so on, relationships among entities in the registry, and standing requests to track changes to a list of entities. UDDI servers are classified into three categories: (i) a node, which is a single UDDI server that is the member of exactly one UDDI registry and is used for supporting interactions with UDDI data through one or more API sets; (ii) a registry, which is composed of one or more nodes and is used for collectively managing a well-defined set of UDDI data; and (iii) affiliates registries, which are individual registries that are used to implement policy-based sharing of information among them and to share a common namespace for UDDI keys that uniquely identify data records.

The Biodiversity Catalogue4 is a centralized, curated catalogue of Web services. Entries in the catalogue describe a Web service from both an informative level and a technical level. The informative level describes such things as the overall functionality, terms of use, contact information, and scientific topics. The technical level provides the manner in which a client can implement an interface with a service, including such things as endpoint descriptions, parameter options, output representations, and templates. The manner in which entries can be registered in the catalogue is via a web form submission; this can be done by members of the community or by dedicated curators. Service Object Access Protocol (SOAP) services with WSDL documents can be parsed automatically and can be amended with additional metadata later. Other types of Web service, such as REST must be entered manually. The Biodiversity Catalogue provides a monitoring service that asserts whether a service is reachable each day. This data, over time, forms a metric for the availability of a Web service over time.

SwaggerHub5 is a catalogue of indexed Web services. Similar to UDDI, Web service providers document their APIs using a specification called Swagger. The specification provides a means to describe the set of technical functionalities and non-technical metadata of a Web service. These documents can then be registered in SwaggerHub, which parses and displays the information for prospective clients to utilize. SwaggerHub comes with tools to automatically generate client code to interface with an API in a wide variety of programming languages, expediting the development process of utilizing an API.

6. Recommendations

Here, below we list a number of recommendations that can help to make the RDS discovery process more efficient and effective.

Concerning the description of a RDS, we suggest the following recommendations:

- At present, guidelines for appropriately describing an RDS are not available. An RDS description must be based on a systematic analysis aimed at revealing those characteristics of RDSs that must be considered in an appropriate RDS model. There is a need for an investigation to be conducted among the members of the research communities in order to collect information about the way researchers are willing to describe their needs for a RDS. Existing approaches to Semantic Web Service description and selection must be evaluated in light of the results derived from such investigation. Similar approaches have been successfully pursued in the Semantic Web Service community. In addition, attempts to catalog research-related services [,] and to model and share scientific workflows [,,] can deliver valuable insights and solutions that shall be taken into account.

- RDS models should be compliant with existing and upcoming W3C standards to benefit from the rich set of tools that have been and will be developed.

- Service models for RDSs shall support the architectural style (SOAP-based [], REST-based, etc.) of services that are prevalent in the Research Data Services domain.

- An RDS should be described at three levels: the computational level, the algorithmic level, and the implementational level (cf. Section 2).

- Ontology-based languages must be used for the description of an RDS as well as for formulating an RDS need. Alternatively, domain-specific vocabularies must be used for annotating RDSs.

- In order to support ontology-based RDS description, each scientific domain must develop its own domain-specific ontologies: one that formally defines the possible data-types of the RDS’s arguments; one that formally describes the possible operations performed by RDSs (functional ontology); and one that describes QoS metrics.

- RDSs should be, like Linked Data, self-describing.

- Existing service models have to be extended to address domain-specific characteristics of RDSs.

- A layered RDS metadata/profile description must be adopted, as it allows a more precise description of the input/output datasets, the data operations, and the non-functional aspects of the RDS.

Concerning the RDS discovery process, we suggest the following recommendations:

- Again, we emphasize the need for an investigation aimed at collecting information about the RDS discovery mechanisms adopted by researchers in order to identify promising candidate solutions for the selection of RDSs among the existing approaches and to track down necessary extensions to these.

- Initiatives similar to the Semantic Web Service challenge [] that compare existing approaches with respect to their functional capabilities are required. These should be complemented by the creation of domain-specific test collections that allow for a performance analysis of developed solutions.

- Potential knowledge representation languages for the description of RDSs must provide appropriate means to describe aspects of such services that are relevant to their discovery.

- Service models and representation languages for which matchmaking tools with appropriate capabilities and performance are available should be preferred. This choice depends on the kind of search mechanism that shall be supported, e.g., automatic discovery, keyword search, faceted search over service types, or query by example) and whether service composition shall be enabled.

- For an efficient RDS discovery process, it is required that the same domain ontology (or vocabulary) be used by both service providers and requesters. Therefore, the basis for specifying operations and input/output data must be widely agreed upon international standards.

- Functionality-based RDS discovery must be the main approach to the RDS discovery.

- A fully automatic RDS discovery process must be put in action.

- There is a need for developing efficient RDS matchmakers.

Concerning the compatibility between RDS description and RDS request we suggest the following recommendation:

- In order to enable compatibility and reuse, RDS models must integrate smoothly with knowledge representation languages and models used to describe (the semantics of) research data (as the input/output of RDSs), metadata, and domain-specific knowledge. These might differ from domain to domain.

Finally, concerning the RDS publication, we suggest the following recommendations:

- Each RDS must be assigned a “Digital Service Identifier” by a registration agency.

- Each scientific domain has to create its own RDS registry where RDSs relevant for this domain are published.

- An institutional commitment must exist on every published RDS. In particular, the non-functional aspects of an RDS must be included in a kind of standardized contract (Service-Level Agreement) between the service provider and the potential consumers that specifies specific and measurable aspects related to the service offerings.

Acknowledgments

This White Paper is the outcome of a Workshop on “Research Data Service Discoverability” held in the Island of Santorini (Greece) on 21-22 April 2016. The Workshop was carried out in the context of the “Research Data Alliance – Europe 3” (RDA-E3) Project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 653194”. We would like to thank all the participants in this Workshop for their contribution, in terms of ideas and suggestions, in the preparation of this White Paper. The Workshop description and the list of participants (only by invitation) are included in the Appendix.

Author Contributions

Costanrino Thanos authored Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5.3, Section 5.4, Section 5.5 and Section 5.6; Friederike Klan authored Section 5.1 and Section 5.2; Kyriakos Kritikos authored Section 5.7; Costantino Thanos and Leonardo Candela are the editors of the White Paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

A.1. Workshop on “Research Data Service Discoverability”

A.1.1. Rationale

Acceptance of the open science principle entails open access not only to research data but also to data services, tools, analyses, and methods that enable researchers to conduct efficiently and effectively their research activities.

Researchers, scientists, data scientists, and practitioners have developed several data services and tools, including data mining, data visualization, data analysis tools, etc. One of the challenges faced by researchers, in a globally networked scientific world, is to be able to locate data services/tools that fulfil their research needs. Efficiency of discovering appropriate data services/tools and possibly composing them to build complex scientific workflows is a requirement of modern science. A crucial aspect in making this happen is the ability to semantically describe the functionality of a service/tool. It becomes increasingly necessary to create registries that maintain semantically enriched descriptions (metadata/profiles) of data services/tools. It is also necessary to develop discovery mechanisms that match the service/tool description against the description of a user need.

Unfortunately, at present, semantic descriptions (metadata) of data service/tools are missing.

The Santorini Workshop will address the problems that hamper efficient data service/tool discoverability and the building of appropriate registries. In particular, the focus of the meeting will be on the different levels of description of a data service/tool, modeling approaches, and discovery mechanisms based on semantic descriptions.

A.1.2. Outcome

We expect that such a workshop will contribute to promote a research activity in a very relevant topic that so far, unfortunately, has not been adequately addressed.

A report will be produced that will identify research problems to be addressed and directions to be followed in order to solve them.

A.1.3. Place

Island of Santorini (Greece) Date: 21-22 April 2016

A.2. List of Participants

Peter Buneman (University of Edinburgh), Oscar Corcho (Universidad Politecnica de Madrid), Mathieu D’Aquin (The Open University UK), Anna Fensel (University of Innsbruck), Nicola Guarino (ISTC-CNR), Friederike Klan (University Jena), Kyriakos Kritikos (ICS-FORTH), Eric Mannens (University of Ghent), Ioan Toma (Semantic Technologies Institute) Yannis Velegrakis (University of Trento).

Research Data Infrastructures: GEOSS (by Stefano Nativi), ELIXIR (by Kristoffer Rapacki) Biodiversity Catalogue (by Niall Beard), OpenAIRE (by Paolo Manghi).

RDA Working Groups: Metadata Standards Catalog (by Alex Ball), Brokering Governance (by Stefano Nativi), Data Type Registries (by Daan Broeder), Metadata Standards Directory (by Alex Ball), RDA/WDS Publishing Data Services (by Paolo Manghi).

Service Providers: EUDAT (by Daan Broeder).

Appendix B. Additional readings

Becker, J.; Mueller, O.; Woditsch, M. An Ontology-Based Natural Language Service Discovery Engine—Design and Experimental Evaluation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Pretoria, South Africa, 7–9 June 2010; p. 166.

Bianchini, D.; De Antonellis, V.; Merchiori, M. Flexible semantic-based service matchmaking and discovery. World Wide Web 2008, 11, 227–251.

Carenini, A.; Cerizza, D.; Comerio, M.; Della valle, E.; De Paoli, F.; Maurino, A.; Turati, A. GLUE2: A Web Service Discovery Engine with Non-Functional Properties. ECOWS Sixth European Conference on Web Services, Dublin, Ireland, 12–14 November 2008.

Dong, H.; Hussain, F.K.; Chang, E. Semantic Web Service Matchmakers: state of the art and challenges. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2013, 25, 961–988.