Abstract

University–industry (U–I) collaborations are widely recognized as key drivers of economic progress, innovation, and competitiveness, fostering significant scholarly interest. Concurrently, research findings on these interactions have contributed to the establishment of an interdisciplinary field marked by the inherent complexity of these relationships. This study aims to map the conceptual structure of university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) research from 1980 to 2023 by employing co-word analysis and social network analysis based on data retrieved from the Scopus database. The results reveal that 1577 documents were published during this period, incorporating 147 keywords, with the five most frequent being “innovation”, “higher education”, “university”, “technology transfer”, and “knowledge management”. The United Kingdom was identified as the most prolific country, contributing 366 documents, while Research Policy emerged as the most cited journal, with 3546 citations. This study offers a comprehensive overview of the current state of UIKT research, paving the way for future studies and providing valuable directions for further investigations.

1. Introduction

Knowledge transfer between universities and industry (U-I) has become an essential pillar for technological advancement, innovation, and global economic development. This bidirectional collaboration between two seemingly disparate sectors plays a crucial role in value generation, job creation, and enhancing competitiveness. In recent decades, universities have undergone a significant shift in their involvement in knowledge commercialization, driven by the need to secure funding and contribute to economic development (Geuna & Muscio, 2009; Muscio, 2010).

Today, knowledge transfer at the university–industry interface is regarded as a key driver of innovation and economic growth, facilitating the commercial application of scientific discoveries within companies. The scientific literature identifies network participation and an institutional culture of support as factors that promote the transfer of research outcomes, whereas limited time and financial resources are recognized as primary barriers (Gaisch et al., 2019). In this context, internet access has become an essential component of modern society, providing information access almost anytime (Azeroual & Koltay, 2022). This capability enhances knowledge dissemination and facilitates access to resources that can strengthen collaboration and knowledge exchange between academia and industry.

Among the various mechanisms available to establish these links, the commercialization of academic knowledge, which includes patenting, licensing of inventions, and academic entrepreneurship, has gained prominence and attracted considerable attention in both the academic literature and the political sphere (Markman et al., 2008; O’Shea, 2007). To support this commercialization, many universities have established specialized structures such as technology transfer offices, science parks, and incubators (Clarysse et al., 2005; Weckowska, 2015).

While commercialization is indeed an important avenue for academic research to contribute to the economy and society, there are other forms of university knowledge transfer (Marullo et al., 2022). One such form, which has garnered interest among organizations and researchers, is academic engagement (Perkmann et al., 2013). This approach involves knowledge-related interactions between academic researchers and non-academic organizations, and it is distinct from teaching and commercialization activities. These interactions include collaborative research, contract research, and consulting, as well as informal activities such as providing ad hoc advice and networking with professionals (Perkmann et al., 2021).

This article aims to map the conceptual structure of university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) research from 1980 to 2023 using co-word and social network analyses. The purpose is to identify the main themes that shape the structure of this research field, as well as its dominant, saturated, fading, and emerging topics. Additionally, it highlights the most frequently cited works authored by tenured faculty members and published in high-impact journals at top-tier universities worldwide, while also outlining prospective directions for UIKT research. To achieve these objectives, this study draws on data from 1577 documents published in the Scopus database, which is currently the leading multidisciplinary database for scientific literature (Salvadorinho & Teixeira, 2021).

This study contributes to the UIKT literature in several ways. First, while bibliometric research has primarily focused on publication patterns based on authorship (Borges et al., 2022; Lundberg et al., 2006; Marijan & Sen, 2022; Tijssen et al., 2009), universities, and research centers (Salleh & Omar, 2013; Tseng et al., 2020), as well as geographical regions (Dang et al., 2024; D’Este & Patel, 2007; Salleh & Omar, 2013; W. Wang & Lu, 2021), these studies provide valuable insights but fail to map the conceptual structure of the discipline (Ding et al., 2001). This study aims to fill this gap by enhancing the understanding of the conceptual structure of UIKT research through co-word and social network analyses. Second, it offers quantitative assessments of UIKT research by adopting a qualitative approach to evaluate the literature in this field. Third, it describes the conceptual structure of UIKT research based on different geographical regions, which can help identify regional trends. Fourth, it provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of UIKT research. Additionally, it paves the way for future studies by identifying research gaps. Therefore, the findings can help researchers better understand emerging trends and guide their future research.

Despite the significant amount of academic literature produced on UIKT in recent decades, the research remains fragmented and inconclusive. It is crucial to identify the key factors in this field and trace its paradigmatic evolution over time. Consequently, examining the conceptual structure of UIKT research as an interdisciplinary field, which has integrated various theories and knowledge from other disciplines, is essential. This study seeks to advance this area by providing new insights into the current paradigms and future research directions. Accordingly, this paper aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the main themes that form the research framework of UIKT?

RQ2: What are the dominant, saturated, fading, and emerging issues in the field of UIKT?

RQ3: How have the themes in UIKT research evolved between 1980 and 2023?

RQ4: Which articles, authors, countries, journals, and universities are the most frequently cited in UIKT research?

RQ5: What are the potential future directions for UIKT research?

2. Theoretical Background

The transfer of knowledge between academia and industry (UIKT) serves as a pivotal driver of innovation and economic growth, facilitating the practical application of scientific advancements in entrepreneurial contexts (de Wit-de Vries et al., 2019). This process not only opens new opportunities for researchers but also enables access to financial resources and contributes to socio-economic development through the commercialization of university-based technologies (Dolmans et al., 2022). Key strategies, such as spin-offs, joint patents, technology licensing, and collaborative projects, strengthen the academia–industry nexus. These initiatives foster the creation of enterprises rooted in academic knowledge, thereby solidifying UIKT’s impact on the knowledge economy (Martínez-Ardila et al., 2023). This approach ensures greater efficiency in transferring outcomes by bridging scientific advancements with the needs of productive sectors.

Universities play a central role in knowledge transfer through activities such as research collaborations, consultancy services, contracts, intellectual property licensing, and strategic partnerships (Rossi & Sengupta, 2022). These interactions diversify the modalities of cooperation between academia and industry, enabling universities to adapt to the varying demands of stakeholders. This approach fortifies the innovation ecosystem, facilitating the development of technological and scientific solutions to address both global and local challenges. By embracing these dynamics, universities position themselves as transformative knowledge agents, fostering bidirectional relationships that benefit both academia and industry (Compagnucci & Spigarelli, 2020). This exchange of resources, capabilities, and expertise not only resolves specific problems but also generates economic and social value. Furthermore, through engagement with industry, government, and society, universities enhance their impact on productive sectors and solidify their contribution to social welfare and economic advancement.

Traditional knowledge transfer mechanisms, including patents, licenses, and spin-offs, are fundamental in translating research outcomes into marketable products and services (Markman et al., 2008). However, public–private partnerships and alternative collaboration models have gained prominence by merging academic knowledge from universities with applied industrial expertise. These partnerships generate significant innovations and tackle socio-economic challenges, highlighting the importance of cognitive, institutional, and geographical proximity in maximizing their impact (Rossi et al., 2024). Moreover, entrepreneurship education has emerged as a critical driver of knowledge transfer by equipping individuals with entrepreneurial skills and competencies that enable the practical application of academic knowledge through innovative solutions (Klofsten et al., 2019).

UIKT is inherently complex, involving academics, industry representatives, and policymakers. Effective coordination at multiple levels of management, from institutional strategies to regional policies, is essential to maximize its impact and foster meaningful synergies (Ferreira & Carayannis, 2019). In this context, knowledge transfer policies have evolved to integrate universities into governance processes and regional strategies. This multi-level framework promotes strategic alignment between university capabilities and regional needs, strengthening collaboration among governments, businesses, and academic institutions. Such an approach ensures a systematic impact on innovation policies and territorial development, optimizing the effectiveness of knowledge transfer initiatives (Fonseca & Nieth, 2021).

Although financial resources derived from academic engagement surpass those generated through the commercialization of research outputs (Perkmann et al., 2021) and are highly valued by industry (Zhang et al., 2024), university–industry interactions have predominantly focused on commercial activities. Since 2009, academic production and interest in this topic have significantly increased (Pham et al., 2024), yet theoretical gaps persist (Appendix A provides a summary of key articles that illustrate the evolution of the field). These collaborations aim to generate innovative knowledge through a bidirectional exchange, addressing relevant problems and developing technologies. Within this framework, academic engagement involves high-commitment research partnerships between academic and industrial actors that are oriented toward joint outcomes (Perkmann & Walsh, 2007). These alliances encompass collaborative research, contracts, and consultancy, excluding interactions devoid of meaningful research activities (Perkmann et al., 2013).

UIKT is essential for driving innovation and fostering economic, social, and technological development. This mechanism, characterized by bidirectional interactions between academic and industrial actors, promotes the generation of applied knowledge and the resolution of complex problems through the integration of diverse resources, capabilities, and perspectives. Universities, as transformative agents, play a critical role in adapting their strategies to the needs of productive sectors and society. However, to maximize the impact of these initiatives, it is crucial for knowledge transfer policies and strategies to evolve toward integrated, multi-level approaches that promote effective synergies among various stakeholders. Furthermore, continued research into UIKT dynamics is indispensable for identifying barriers, optimizing practices, and ensuring its sustainability as a catalyst for economic and social progress.

3. Research Methods

This study aimed to systematically review academic research on UIKT from 1980 to 2023. Building on earlier works (Bastos et al., 2021; Mascarenhas et al., 2018; Skute et al., 2019; Woltmann & Alkærsig, 2018), co-word analysis and social network analysis were utilized (using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20) to map out the conceptual framework of UIKT research. Detailed descriptions of these methods are provided below.

3.1. Co-Word Analysis

The technique of co-word analysis was first introduced by Callon et al. (Callon et al., 1986). Since then, numerous studies have employed this method to map the bibliometric structure of various fields, such as social media (Leung et al., 2017), tourism recovery (Shao et al., 2021), brand equity (Rojas-Lamorena et al., 2022), and social entrepreneurship (Tan Luc et al., 2022). Co-word analysis is recognized as an effective method for content analysis and text mining (Zhu & Zhang, 2020). Its main strength lies in its ability to reveal the conceptual structure of a discipline without the need to review the entire text (Romo-Fernández et al., 2013).

This technique is based on the premise that the co-occurrence of two or more keywords in a document indicates a correlation between them, and the higher the frequency of co-occurrence, the stronger their relationship (Callon et al., 1986; Ravikumar et al., 2015). Another fundamental assumption is that authors carefully select keywords to accurately represent the content of their works (Feng et al., 2017). Co-word analysis also acts as a link between disciplines, connecting seemingly separate fields, highlighting interdisciplinary relationships, and promoting collaboration among researchers from various areas. This tool builds intellectual bridges in the vast landscape of knowledge and contributes to the development of taxonomies and ontologies that organize and structure information in each area, thus facilitating the navigation and understanding of key concepts within the domain. Furthermore, this method can be used to quantify the links between research topics within a scientific discipline; identify domains, subdomains, and relevant categories (Hu et al., 2013); and predict future research trends (de la Hoz-Correa et al., 2018).

3.2. Social Network Analysis

The application of social network analysis (SNA) has become indispensable in the examination of academic output, providing a unique and profound perspective on how researchers, publications, and institutions are interconnected within the academic sphere (Freeman, 2004). This intersection between SNA and academic production is crucial for understanding the dynamics of knowledge generation and dissemination in the scientific community. Central to the analysis of academic output is the concept that scientific publications are not isolated entities but are part of a complex web of relationships. This technique maps and explores these relationships, offering a comprehensive view of how authors collaborate, how scientific journals interact, and how institutions are linked through their research contributions (C. Wang et al., 2014).

One of the most notable applications of SNA in this context is the analysis of co-authorship. When multiple researchers collaborate on a scientific paper, connections are established among them. SNA allows for the identification of collaboration patterns, the recognition of key actors in a research network, and the discovery of emerging thematic communities (Abbasi et al., 2011). This is essential not only for evaluating the quality of scientific collaboration but also for identifying trends and areas of interdisciplinary research. Additionally, SNA is employed to analyze citations among researchers and publications, facilitating the identification of the most influential works, tracking the spread of ideas within the scientific community, and assessing the relevance of a publication based on its position in the citation network (Isfandyari-Moghaddam et al., 2023).

Network visualization, a critical tool in SNA, provides an intuitive way to represent these complex relationships. In these visualizations, nodes represent researchers, publications, or journals, while links symbolize collaborations, citations, or thematic relationships. These visual representations can reveal surprising patterns and assist researchers in making informed decisions about knowledge management and strategic research planning (Camacho et al., 2020; Yousefi Nooraie et al., 2020). The implementation of this technique in the study of academic production has enriched the understanding of how knowledge is generated and disseminated in the scientific domain. By uncovering the underlying connections within the academic community, not only does it provide a deeper insight into the dynamics of research, but it also offers valuable tools for decision-making in its management and the assessment of academic quality. This interdisciplinary integration promises to continue driving significant advancements in the generation and dissemination of knowledge in the academic field.

3.3. VOSviewer

VOSviewer has emerged as a powerful computational tool in the field of bibliometrics, standing out as an essential resource for the construction and visualization of various bibliometric networks. Its versatility and functionality make it a preferred choice for researchers aiming to analyze and better understand academic and scientific production in a specific area (Arruda et al., 2022). It facilitates the creation and visualization of a variety of bibliometric networks, including those of journals, researchers, and articles. What sets VOSviewer apart is its ability to handle multiple types of relationships, such as citation, bibliographic coupling, co-citation, and co-authorship. This enables users to explore and visually represent how scientific publications are interconnected, identify frequently collaborating authors, and see how journals are grouped by thematic similarities and citation connections.

In addition to its primary function of bibliometric network visualization, VOSviewer offers text mining tools that further deepen the analysis. Users can extract relevant keywords from a corpus of literature and use this information to construct and visualize co-occurrence networks of keywords. This feature is particularly useful for identifying emerging topics, research trends, and conceptual relationships in a specific field (Bukar et al., 2023). In summary, VOSviewer has established itself as a comprehensive and versatile tool in bibliometrics and academic production analysis. Its capability to construct and visualize bibliometric networks based on various relationships, coupled with its text mining tools, provides researchers with a powerful means to explore the interconnection and evolution of scientific knowledge across diverse disciplines. Its ease of use and advanced capabilities make it a valuable option for those wishing to delve deeper into the analysis of the scientific literature and better understand the dynamics of research.

3.4. Definition of the Research Field

As highlighted in the introduction, there is a pressing need to conduct a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) research. Accordingly, this study focuses on providing a detailed overview of the scientific output, collaboration networks, and, most notably, a co-word analysis to map the conceptual structure of this interdisciplinary field.

3.5. Data Collection, Refinement, and Standardization

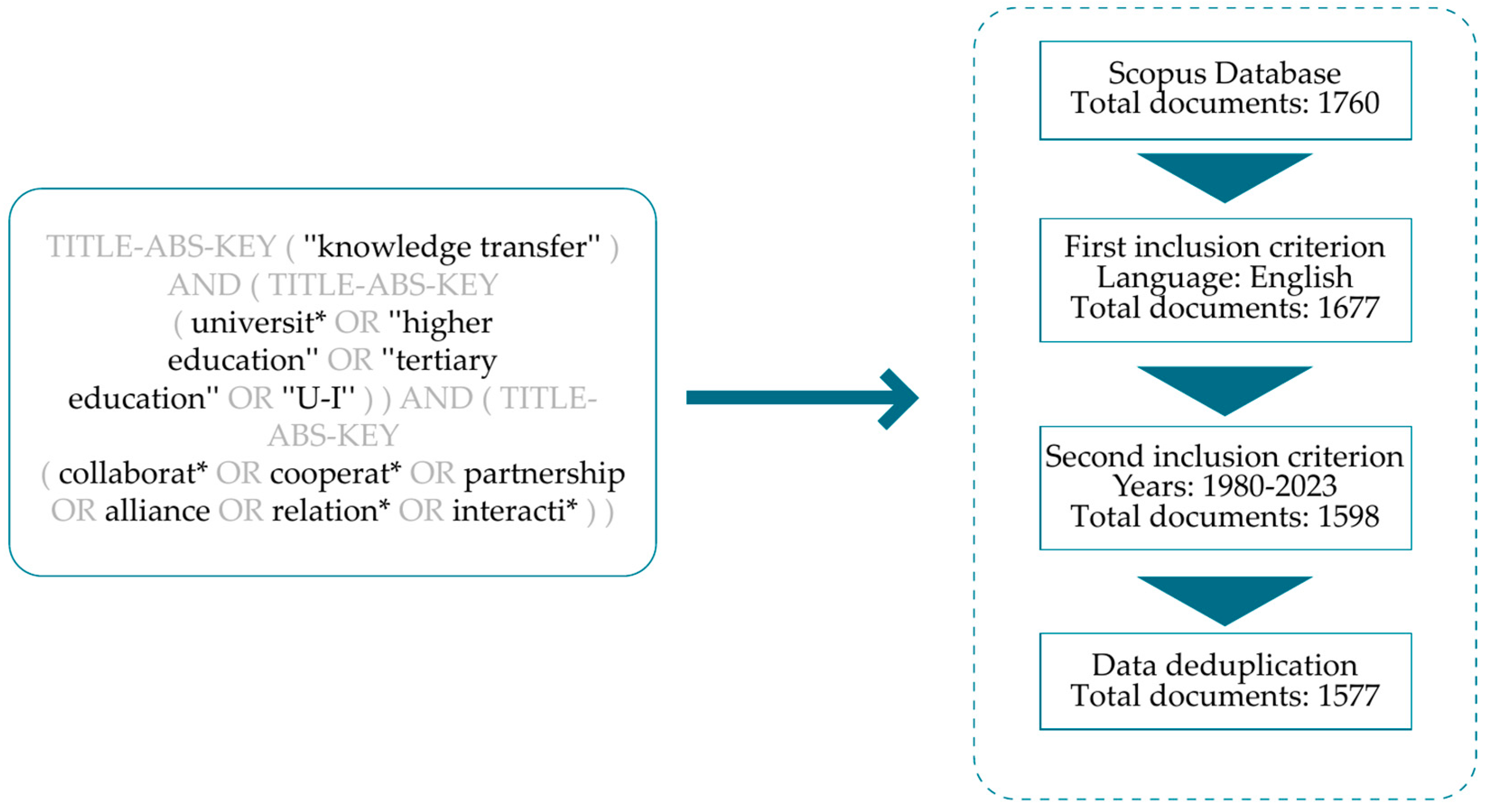

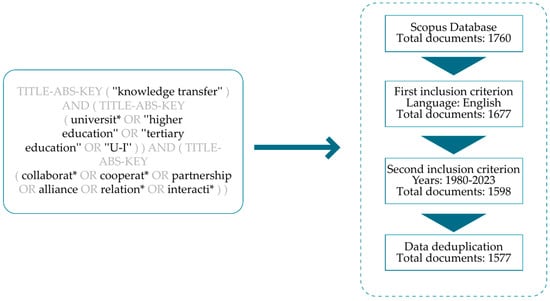

On 30 July 2024, bibliographic metadata on university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) were exported from the Scopus database into a comma-separated values (CSV) file. These metadata included author names, document titles, keywords, affiliations, publication years, and citation counts, all of which are critical components for a comprehensive bibliometric analysis. The search query incorporated terms such as “knowledge transfer”, “university”, “higher education”, “collaboration”, and “partnership”, as shown in Figure 1, yielding an initial dataset of 1760 documents. The dataset was refined by applying the inclusion criteria, retaining only documents written in English (1677) and published between 1980, the year of the earliest article on this topic available in the Scopus database, and 2023 (1598). After deduplication, the final dataset comprised 1577 documents.

Figure 1.

Data collection framework.

To ensure consistency and accuracy, a disambiguation process was conducted to standardize keyword variations, such as “university” versus “universities” and “partnership” versus “partnerships”. This process was implemented using OpenRefine (version 3.7.9), an open-source tool for data cleaning and transformation. The CSV file was imported into OpenRefine, where the keyword column was analyzed for inconsistencies. Using the “Text Facet” feature, variations in terms were identified and grouped. A thesaurus file was created to map each variation to a standardized term. This thesaurus was then applied within OpenRefine to harmonize the terminology across the dataset. This approach ensured the dataset’s integrity, enabling precise and reliable bibliometric analysis. Figure 1 provides a detailed overview of the data collection, refinement, and standardization process.

4. Findings

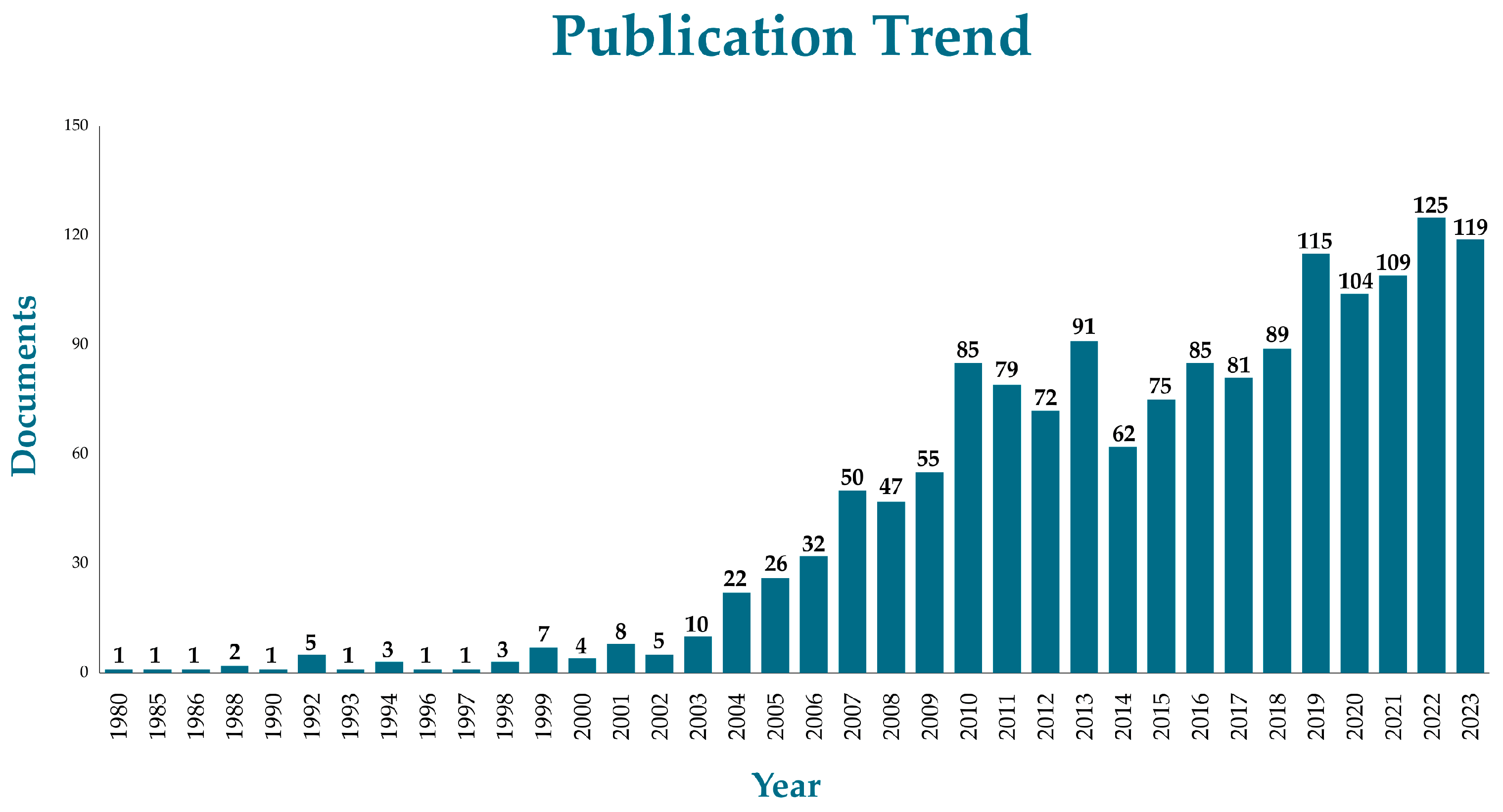

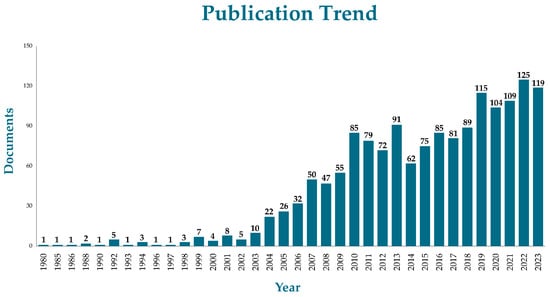

The overall trend in publications from 1980 to 2023 demonstrates a sustained upward trajectory, with the data reflecting the annual number of publications related to university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT). Over the past two decades, this topic has garnered increasing attention from researchers. As illustrated in Figure 2, which presents the number of publications per year, a total of 1577 documents were identified. The year 2022 registered the highest output, with 125 publications, highlighting the growing interest in this field.

Figure 2.

Publication trend in UIKT between 1980 and 2023.

4.1. Keyword Frequency and Trends

Co-occurrence refers to the presence, frequency, and proximity of keywords within multiple articles, revealing underlying research themes (Romo-Fernández et al., 2013). This technique is fundamental for analyzing academic output as it uncovers semantic relationships between terms in scientific documents, enabling the identification of emerging trends and the mapping of knowledge structures. By examining the co-appearance of key terms, researchers gain valuable insights into thematic connections and evolving topics within a field of study. Furthermore, this approach enhances information retrieval efficiency and supports the visualization of knowledge networks, benefiting researchers and professionals in understanding and advancing their areas of expertise.

As previously described, OpenRefine was employed to process and standardize the dataset, ensuring consistency and accuracy in the keywords used for analysis. After standardization, a total of 3867 unique keywords from documents published between 1980 and 2023 were analyzed for their frequency and thematic relevance. Table 1 presents the 20 most frequent keywords, offering insights into the dominant themes and research directions within the field of university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT). This analysis highlights the conceptual focus and evolution of the research area over the studied period.

Table 1.

Top 20 keywords.

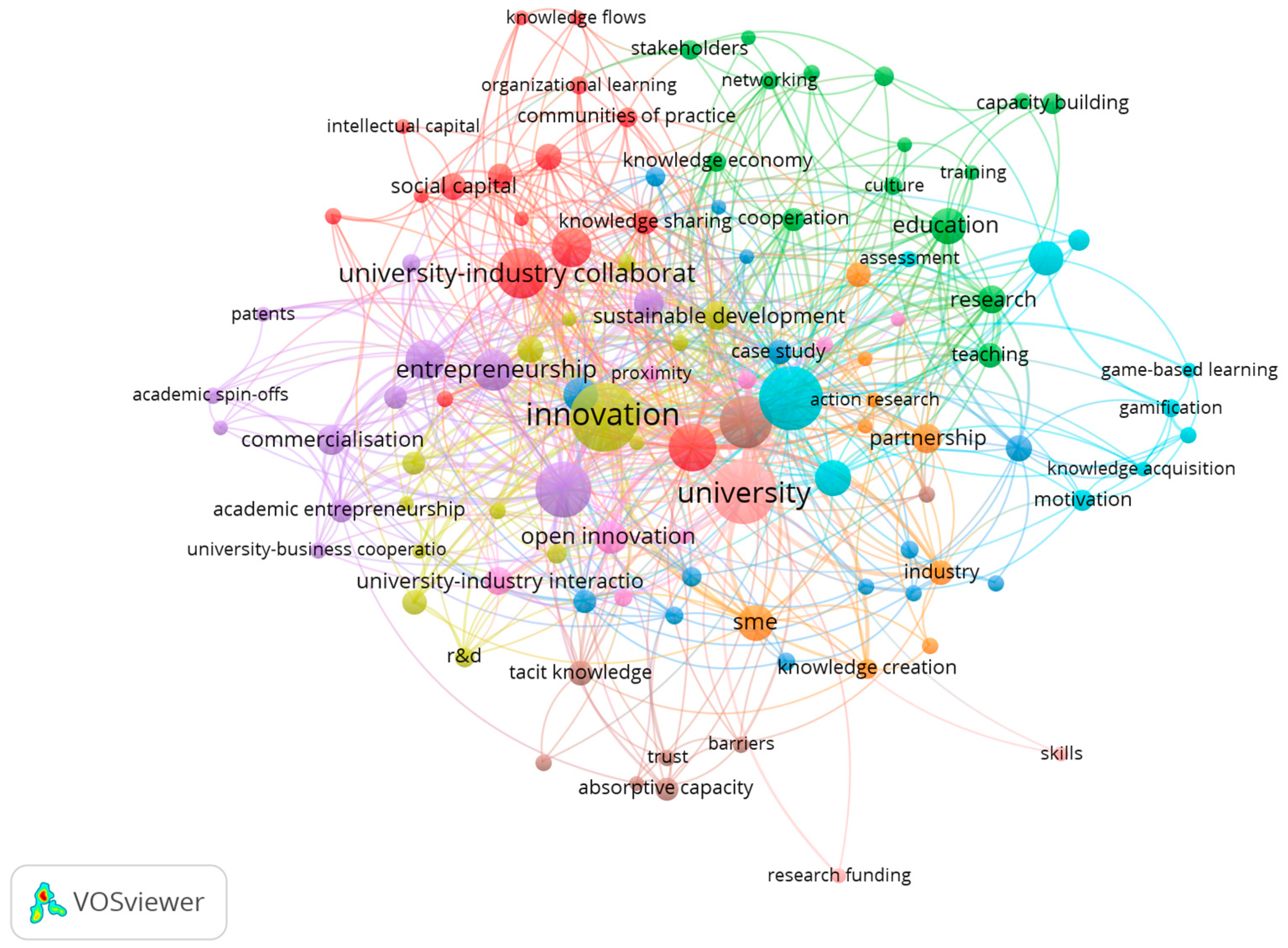

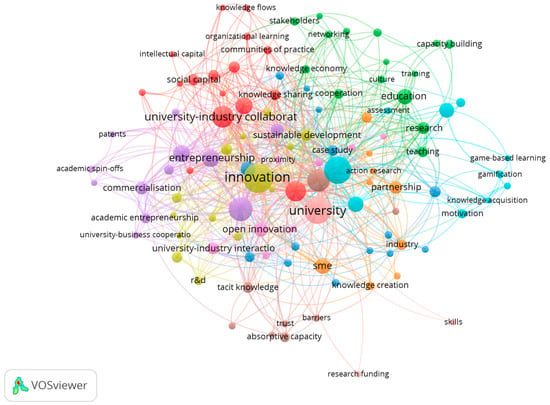

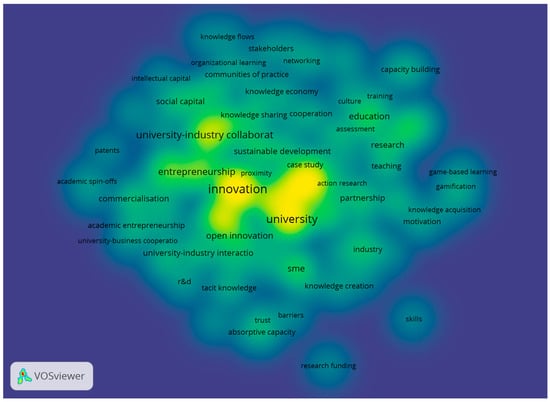

Figure 3 illustrates a co-occurrence network where the most frequently appearing keywords are organized into six distinct clusters, each represented by a different color. Keywords with related themes are grouped within the same cluster. For instance, “university-industry collaboration” and “knowledge transfer” are positioned within the red cluster, while “innovation” and “sustainable development” belong to the green cluster. The size of each circle corresponds to the frequency of the respective keyword, whereas the thickness of the connecting lines represents the strength of co-occurrence both within and between clusters. As depicted in the figure, all clusters are interconnected, indicating strong relationships among them and suggesting a high degree of interdependence across various research areas within UIKT.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network of keywords (1980–2023).

The co-occurrence network analysis reveals six major clusters, each representing a specific thematic focus within the broader framework of university–industry collaboration, innovation, and knowledge management. The first cluster, shown in red, centers on university–industry collaboration and knowledge management, featuring key terms such as “university-industry collaboration” and “knowledge management”. This highlights the mechanisms by which institutions collaborate to generate and manage knowledge essential for developing new technologies and processes. The second cluster, depicted in blue, emphasizes innovation and university–industry linkages, with terms like “innovation” and “university-industry links”, underscoring the crucial role of collaboration between academia and industry in fostering new ideas, products, and processes. In contrast, the third cluster, represented in green, addresses themes of sustainable development and capacity building, with terms such as “sustainable development” and “capacity building”, pointing to the integration of sustainable practices in university–industry partnerships.

The remaining clusters further expand on specialized topics within the field. The fourth cluster, in purple, focuses on academic entrepreneurship and commercialization, highlighting terms like “entrepreneurship” and “academic entrepreneurship”, which reflect the role of universities in encouraging entrepreneurial activities and facilitating the commercialization of innovations. The fifth cluster, highlighted in yellow, explores open innovation and tacit knowledge, with terms such as “open innovation” and “tacit knowledge”, emphasizing external collaboration in innovation processes and the significance of implicit, non-codified knowledge. Finally, the sixth cluster, in orange, focuses on research funding and absorptive capacity, with terms such as “research funding” and “absorptive capacity”, underscoring the importance of financial resources and the ability of organizations to assimilate and utilize new knowledge. Collectively, these clusters demonstrate the interdisciplinary and interconnected nature of research in university–industry collaboration, reflecting the complex and multifaceted character of this field.

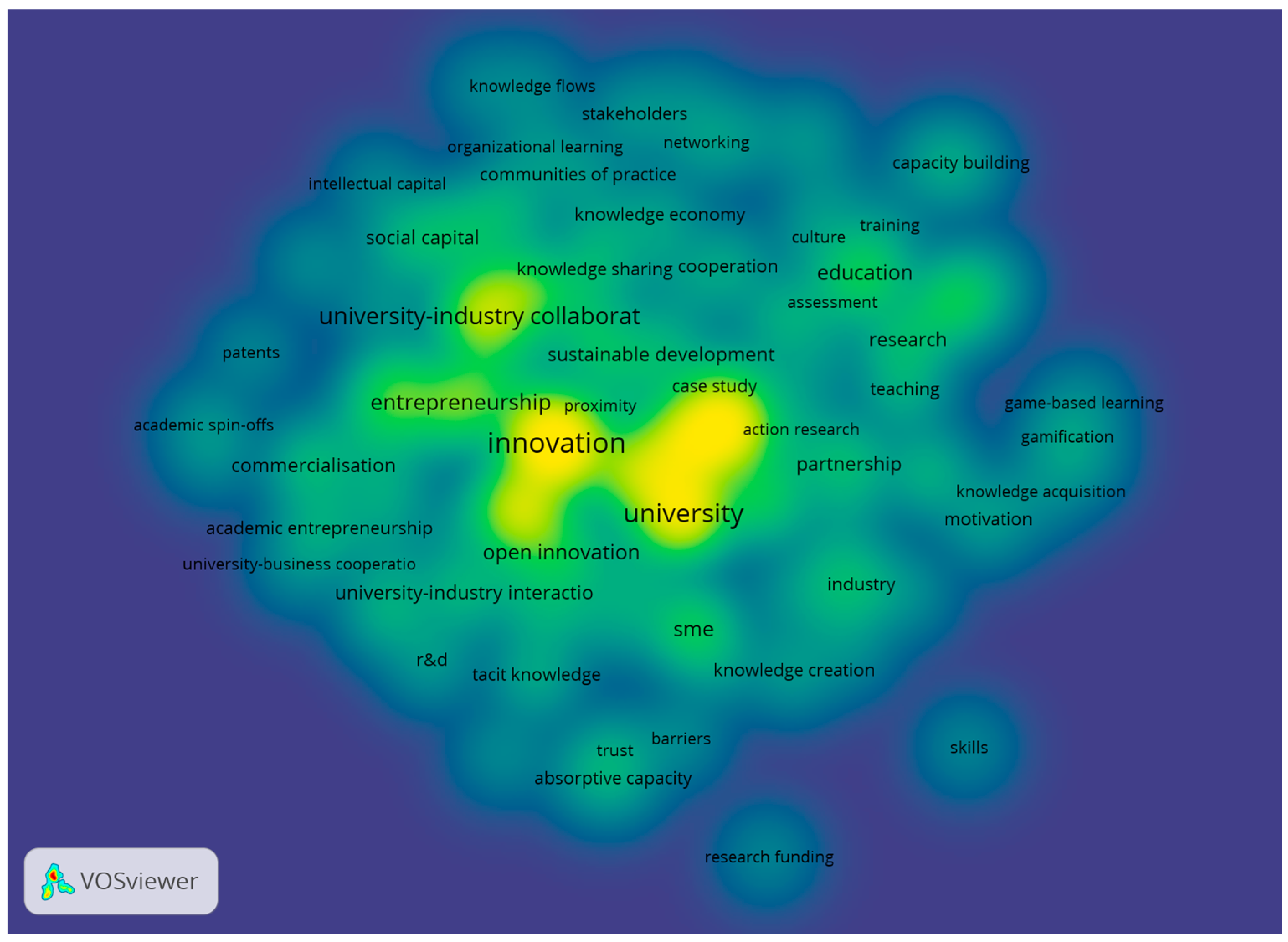

Figure 4 displays the density map generated by VOSviewer, illustrating the frequency and prominence of various keywords in the research on UIKT. The brighter areas of the map, particularly those in yellow and bright green, emphasize the keywords most frequently cited in the literature. Prominent terms such as “innovation”, “university”, and “university-industry collaboration” are situated in these high-density regions, indicating their centrality and widespread discussion within this field of study. In contrast, keywords such as “knowledge management”, “capacity building”, “open innovation”, and “knowledge creation” appear in lower-density areas and are represented by less intense green tones. While these terms are significant, they do not exhibit the same frequency or centrality as those found in the brighter regions of the map.

Figure 4.

Keyword density map (1980–2023).

The map also reveals a distribution of terms, with those related to innovation and university–industry collaboration forming a tightly interconnected core. Conversely, concepts such as “research funding”, “skills”, and “absorptive capacity” appear more peripheral, suggesting that although these concepts are relevant, they may be more specialized or less integrated with the central themes. In conclusion, the map highlights that UIKT research is predominantly focused on innovation and university–industry collaboration, with these topics occupying a central position in the literature. Keywords in lower-density regions likely represent important but more specialized or emerging areas within the broader UIKT research landscape.

4.2. Most Frequently Cited Articles

Table 2 presents the ten most frequently cited articles. The data reveal that the article titled “Toward a New Economics of Science” is the most frequently cited in the UIKT field, accumulating a total of 1604 citations. This information is crucial for researchers and readers in identifying the field’s most impactful studies.

Table 2.

Ten most frequently cited documents.

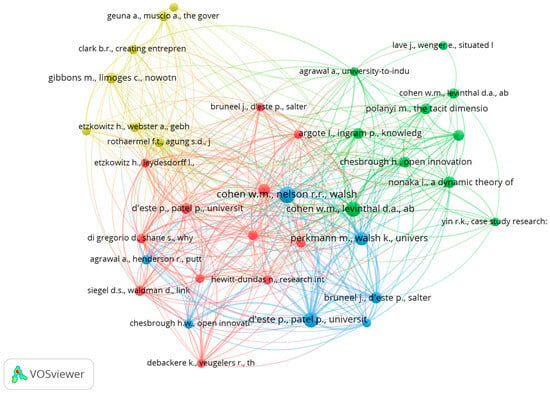

The co-citation analysis identified the seminal publications that have shaped the evolution of the field, as illustrated in Figure 5. A total of 36 documents exceeded the threshold of 15 co-citations and are organized into four clusters, with 377 connections and an aggregate link strength of 844. The largest cluster, represented in red, is anchored by the paper “Links and Impacts: The Influence of Public Research on Industrial R&D”, which boasts a link strength of 141, highlighting its central role within the network (Cohen et al., 2002). Similarly, the works of (D’Este & Patel, 2007) and (Perkmann & Walsh, 2007) rank among the most influential, with link strengths of 121 and 93, respectively, underscoring their significance in the analysis of university–industry relations.

Figure 5.

Co-citation network (1980–2023).

Conversely, the green cluster is distinguished by the research of (Di Gregorio & Shane, 2003), which explores why some universities generate more start-ups than others, with a link strength of 69. The yellow cluster encompasses studies on the governance of knowledge in universities, such as (Geuna & Muscio, 2009), which has a link strength of 66. The foundational work of (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) on absorptive capacity is also highly influential, with a link strength of 81, underscoring the critical role of this concept in understanding university–industry interactions. Together with other key contributions, including those by Bruneel et al. (2010) and (Rothaermel et al., 2007), these studies are pivotal for comprehending the co-citation structure within this scientific domain.

4.3. Top Authors

Table 3 presents the top ten authors based on the number of publications. According to these data, Alessandro Muscio stands out as the most influential author in the UIKT field, with a total of 10 published documents. This information can serve as a useful guide for identifying the most influential researchers in this area.

Table 3.

Top authors.

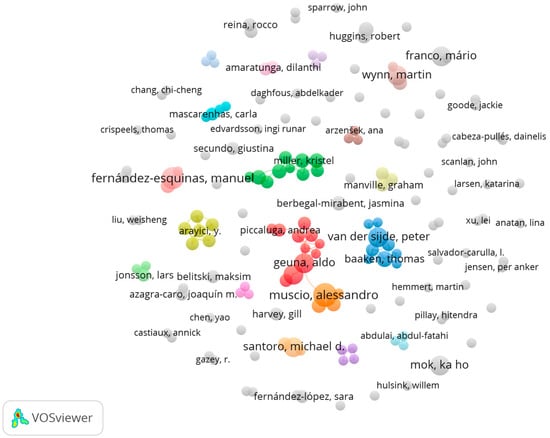

Figure 6 shows the co-authorship network, a tool commonly used in research to examine the collaborative structure of a field of study (Kumar, 2015; Martinho, 2021; Mourao & Martinho, 2020; Uddin et al., 2012). In this case, the network includes prominent authors who have made significant contributions to the field. The figure represents those researchers who have published a minimum of two articles and have received at least 10 citations, which allowed for the identification of a key group of 166 authors.

Figure 6.

Co-authorship network (1980–2023).

These authors are grouped into 84 collaboration clusters, with a total of 134 connections. The strength of the links within the network reaches 248, reflecting the level of interaction between the researchers. Various collaborations can be observed in this network. For instance, “Fernández-Esquinas, Manuel” has collaborated several times with “Muscio, Alessandro” and “Geuna, Aldo”, forming a cohesive network within their cluster. However, while “Muscio, Alessandro” has also collaborated with “Baaken, Thomas”, these interactions have not been sufficiently frequent to establish a more cohesive co-authorship network.

4.4. Top Countries

Table 4 presents the ten leading countries in terms of research output. The United Kingdom stands out as the most prolific, accounting for approximately 28% of all publications on UIKT. It is followed by the United States, which contributes around 13% of the articles, while Germany ranks third with approximately 12%. Notably, there is a significant gap in the volume of publications between the United Kingdom and the countries ranked below it.

Table 4.

Top countries.

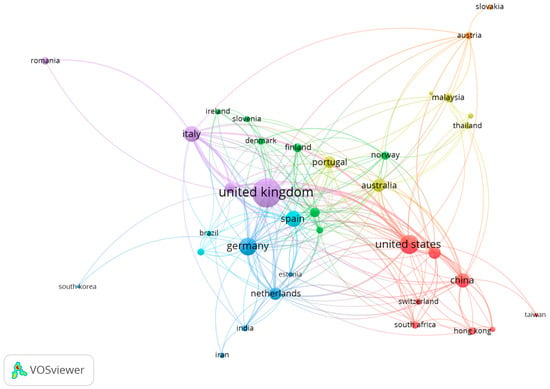

Figure 7 illustrates the co-authorship network among countries, highlighting the participation of 134 nations in scientific production based on author affiliations. However, only 36 countries met the minimum threshold of five publications and 100 citations, forming a network composed of 36 nodes that are organized into seven collaboration groups. In total, the network comprises 204 connections and an accumulated link strength of 484. The size of each node in the network reflects the volume of publications associated with a country through international collaboration, with the largest nodes, such as those of the United Kingdom, United States, and Italy, indicating more active participation in global research.

Figure 7.

Co-authorship network of countries (1980–2023).

The size of the nodes in the network is directly related to the number of publications linked to a country through international cooperation. For instance, the United Kingdom stands as a central player with a total link strength of 137, underscoring its key role in global scientific collaboration. The lines connecting the countries represent the frequency of collaborations, with thicker lines symbolizing stronger or more frequent associations, such as those between the United Kingdom and the United States. Other countries, like Germany and Spain, also hold relevant positions with considerable volumes of publications and international connections, underscoring the importance of global collaborations in scientific production.

4.5. Top Journals

Table 5 provides a summary of the top ten journals ranked by the number of citations. These data are highly valuable for researchers seeking to identify the most influential journals in the field of UIKT for publishing their results. It is worth noting that Research Policy leads in citations, accumulating a total of 3546.

Table 5.

Top journals.

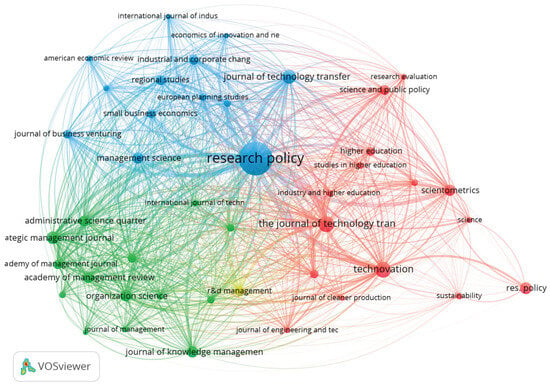

Figure 8 further illustrates the co-citation network among journals, enabling the identification of the most influential publications in the field of UIKT. The analysis revealed 23,711 co-citations, focusing on journals with a minimum of 100 citations. A total of 43 journals met this criterion. The network is structured into four distinct clusters, encompassing 43 journals, 878 links, and a total link strength of 217,967. These metrics offer a detailed view of the leading journals in the field, mapping out the interconnections that drive research trends in UIKT. This network analysis not only highlights the most frequently cited journals but also reveals the thematic clustering of these publications, offering a clearer understanding of their role and influence within specific areas of research.

Figure 8.

Co-citation network of journals (1980–2023).

The co-citation analysis organizes these journals into well-defined clusters, each representing a specialized domain of inquiry. Cluster 1 is dominated by Research Policy, which stands as the most influential journal with 3546 citations and a total link strength of 95,997, underlining its centrality in the domain of science and technology policy. The Journal of Technology Transfer follows with 819 citations and a total link strength of 34,232, while Technovation accumulates 806 citations and a total link strength of 25,746, reflecting their critical contributions to research on innovation and technology transfer. Cluster 2 includes prominent management journals such as Strategic Management Journal, with 508 citations and a total link strength of 17,590, and the Academy of Management Journal with 278 citations and a total link strength of 9909, emphasizing their focus on organizational and strategic management studies.

Cluster 3 features key publications like the American Economic Review, which has 116 citations and a total link strength of 4407, and Management Science with 381 citations and a total link strength of 14,316, underscoring their ongoing influence in the fields of innovation economics and management. Finally, Cluster 4 is represented solely by R&D Management, highlights its unique focus on the management of research and development activities, with 320 citations and a total link strength of 11,499. Together, these clusters provide comprehensive insights into the structure of knowledge across multiple disciplines, underscoring the leading journals that shape the direction of research in these interconnected fields.

4.6. Top Universities

Table 6 highlights the top ten universities ranked by the number of published articles. This information is particularly valuable for researchers seeking to identify institutions actively engaged in UIKT research for potential collaborations. The analysis reveals a total of 3105 universities and research institutes contributing to UIKT studies, with Universidade da Beira Interior leading the field, having produced 18 research publications. It is noteworthy that nine of the top ten universities are based in Europe, underscoring the substantial investment and commitment of European institutions to advance research in this critical area.

Table 6.

Top universities.

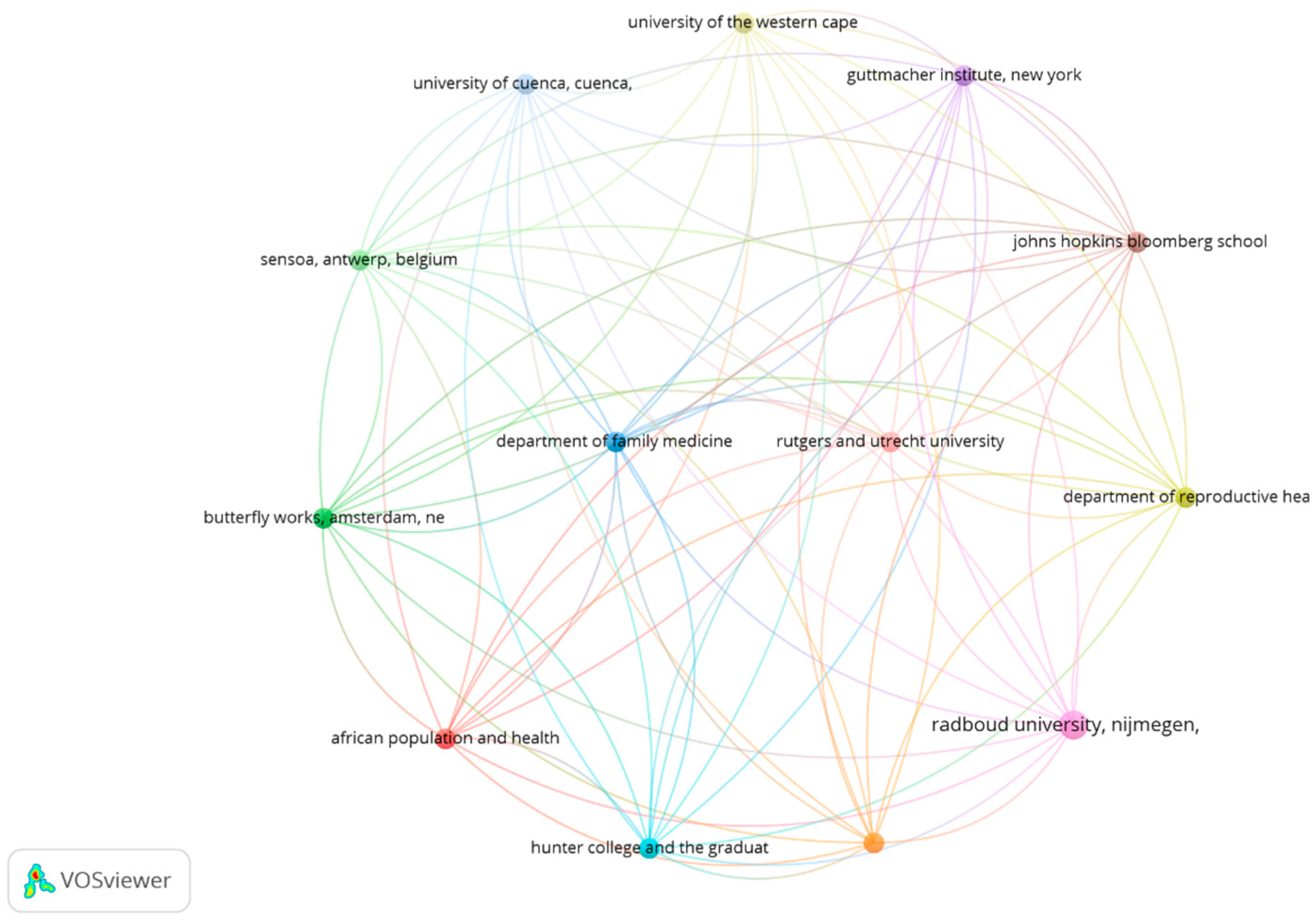

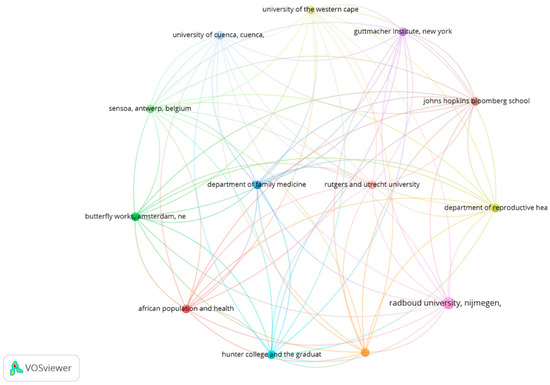

Figure 9 illustrates the co-authorship network among institutions in the context of university–industry knowledge transfer, where each node represents an academic or industrial organization, and the connecting lines indicate the frequency and strength of their collaborations. A total of 3119 universities and research institutes contributed to publications, as determined by the organizational affiliations of the authors. Of these, 950 universities met the threshold of at least one document and 14 citations, underscoring their active participation in the knowledge transfer ecosystem. The size of each node reflects the volume of publications or collaborations, while the thickness of the connecting lines denotes the intensity of interactions. Universities such as the “Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health” and the partnership between “Rutgers University and Utrecht University” stand out for their frequent and extensive collaborations with institutions like “Radboud University” and “Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH)”. Thicker lines represent more frequent collaborations, while larger nodes indicate higher levels of collaborative activity.

Figure 9.

Co-authorship network between universities (1980–2023).

The network is organized into color-coded clusters representing thematic or sectoral groupings within university–industry knowledge transfer. For instance, the purple cluster includes institutions such as the “Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health” and the “Guttmacher Institute”, highlighting a shared focus on public health and biotechnological innovations. The green cluster, featuring “Butterfly Works” and “Sensoa”, reflects a concentration on community development initiatives and technology transfer for social impact. Meanwhile, the red cluster, which includes the “African Population and Health Research Center”, focuses on knowledge transfer in population health and sustainable development in industrial contexts. These clusters underscore the thematic and sectoral diversity of interactions, emphasizing the role of key institutions as bridges connecting different areas of research and innovation, thereby facilitating effective knowledge exchange between academia and industry.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the published articles in the field of university–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) from 1980 to 2023 by employing co-word analysis and social network analysis techniques. The findings reveal a significant increase in the number of publications in this area in recent years, reflecting the academic community’s growing interest in university–business collaboration. This research offers a clear view of the current state of UIKT studies, enhancing our understanding of its conceptual framework and helping to identify gaps in the existing literature, as well as potential future research directions to address unexplored areas.

The first research question explores the main themes that shape the UIKT research framework. Through a co-word analysis for the mentioned period, the results showed that the most frequently recurring keywords were “innovation”, “higher education”, “university”, “technology transfer”, and “knowledge management”. These terms underscore the most relevant aspects of university–business interaction, highlighting innovation as a central pillar of this relationship. Universities, as generators of knowledge, drive technological advances, while technology transfer serves as the vehicle for applying these advances in the productive sector, generating tangible impact on the industry.

Furthermore, the notable increase in scientific production related to UIKT over the last two decades underscores the growing importance of this field of study. More than 95% of UIKT-related scientific articles have been published in the last 20 years, clearly indicating an acceleration in research on this interaction. This steady growth in publications suggests an increasing academic interest in understanding and improving the mechanisms of collaboration between academia and the business sector. As this trend continues, the effective integration of academic knowledge into the productive sector becomes a crucial factor in driving technological and economic development in a world increasingly reliant on innovation and effective knowledge transfer.

To answer the second research question, a keyword density map was used to reveal the main trends in this field’s research. The dominant themes, which appeared in the densest nodes and brightest tones, included terms such as “innovation”, “university”, “entrepreneurship”, and “university-industry collaboration”. These concepts are the most studied in the current literature, reflecting the crucial role that innovation and university–business collaboration play in technological advancement and economic growth.

Saturated topics, which continue to appear frequently but have reached a point of maturity in research, included “higher education” and “open innovation”. These themes have been extensively addressed in the scientific literature, suggesting that their research may be stabilizing. Although still important, their exploration in new studies may decline given the high level of attention they have already received in recent years.

In contrast, topics such as “patents” and “commercialization” showed a decline, appearing in less dense areas of the graph, which indicates reduced attention in recent research. On the other hand, emerging themes like “absorptive capacity”, “knowledge creation”, “trust”, and “gamification” are gaining interest and relevance. These concepts, located in more peripheral yet connected areas, suggest new directions for future research in UIKT, with an increasing focus on how organizations absorb and manage knowledge, as well as how trust and gamification can enhance collaboration between universities and businesses.

To address the third research question, key changes reflected in Figure 4 must be analyzed. During the early years, from 1980 to the early 2000s, the most recurring themes revolved around terms such as “patents”, “commercialization”, and “technology transfer”, emphasizing the focus on intellectual protection and the commercialization of academic knowledge. These concepts were central to the initial studies that examined how universities transferred knowledge and technologies to businesses. Since the 2000s, UIKT research has shifted towards more strategic and integrative concepts such as “innovation”, “university”, “entrepreneurship”, and “university-industry collaboration”, which have become the most dominant themes in the graph. In recent years, new approaches such as “absorptive capacity”, “trust”, “knowledge creation”, and “gamification” have emerged, suggesting a growing interest in how organizations can enhance knowledge absorption, strengthen trust between universities and businesses, and employ new tools like gamification to facilitate knowledge transfer. This evolution reflects a deeper understanding of UIKT dynamics, focusing on broader and more complex aspects of university–business collaboration.

The fourth research question addresses the most cited articles, leading authors, prominent countries, key journals, and leading universities in the UIKT field. The results show that the article titled “Toward a new economics of science”, published in 1994, is the most cited, with 1604 citations. Alessandro Muscio is the leading author, with 10 publications. The United Kingdom is the leading country, with 366 documents out of a total of 1577. The results also indicate that “Research Policy” is the most cited journal, with 3546 citations. The most prolific institution in terms of research is “Universidade da Beira Interior”, with 18 publications. These findings provide researchers with insights into the most influential articles, authors, countries, journals, and universities in the UIKT field.

To address the fifth research question, it is essential to explore new areas, such as social engagement, where universities not only focus on commercial outcomes but also on co-creating value with society through social innovation and civic engagement (Perkmann et al., 2021). It is recommended to delve deeper into the role of geographic and industrial factors by analyzing how local economic development, demand, and the availability of skilled human capital influence the effectiveness of knowledge transfer. Additionally, it is necessary to examine geographic proximity and the type of collaborative partner to better understand how local and international collaborations affect innovation and knowledge exchange between universities and businesses (Audretsch et al., 2023). Regarding clusters and technology parks, longitudinal studies are suggested to monitor their processes over time, allowing for a clearer understanding of network dynamics and their impact on knowledge dissemination. Moreover, comparative studies between different regions are relevant for analyzing how knowledge creation and transfer vary depending on geographic, industrial, and organizational contexts (Fioravanti et al., 2023). It is also important to investigate how knowledge transfer processes differ across industrial sectors and geographic regions and to conduct research that examines the evolution of collaboration networks over time, which would enrich the understanding of knowledge transfer dynamics in UIKT (Szulczewska-Remi & Nowak-Mizgalska, 2023). Finally, it is recommended to study external factors, such as the legislative framework and government support, that influence the creation of spin-offs, as well as the impact of university–industry collaboration on their life cycle, including survival, growth, and the strategic and academic factors that contribute to their success (Odei & Novak, 2023).

Other conclusions drawn from this literature review are presented below. University–industry knowledge transfer (UIKT) encompasses a variety of activities that differ in relational intensity, requiring a deeper analysis to fully understand their effects. Some of these activities, such as joint research, are highly collaborative, while others, like licensing and spin-offs, tend to involve fewer interactive exchanges. It is essential to reconsider knowledge transfer as a bidirectional process, where the involved parties not only transmit knowledge but also exchange and adapt knowledge, skills, and experiences. Although there is a significant body of studies on these activities, more research is needed on how they facilitate the exploitation and adoption of knowledge, which could significantly enhance the effectiveness of knowledge transfer.

One of the main challenges in collaborative research lies not in the approach itself, but in the motivations and behaviors of the actors involved. Academics are generally driven by professional status and recognition, rather than financial rewards, which are considered secondary by most. In contrast, the industry places a high value on trust in academic partners, and while geographic proximity is important, it is not enough by itself to strengthen ties. Factors such as knowledge proximity and the customization of relationships are crucial for managing expectations and ensuring the effectiveness of collaborations. These elements should be explored in greater depth, as they directly influence the sustainability and mutual impact of university–industry interactions.

The barriers limiting UIKT have been well documented, but further detailed analysis is needed. These barriers are primarily related to knowledge limits, especially in emerging fields where actors lack prior experience. Additionally, there are institutional and individual barriers, such as a lack of time, incentives, and bureaucracy. From a contextual perspective, barriers are identified based on differences in incentives and objectives, as well as transactional barriers, such as intellectual property conflicts and university regulations. However, these barriers are not uniform across all UIKT activities, as some, like commercialization and patents, present specific barriers that do not affect more collaborative activities such as joint research or consultancy. This highlights the need for more specific research to address barriers according to each type of UIKT activity.

Regarding the results of knowledge transfer, the literature tends to focus on tangible outcomes, such as knowledge products. However, intangible results, such as ideas for new projects, the opening of new research areas, or even negative outcomes, have been significantly underestimated. This omission may explain why knowledge transfer is not always perceived as effective. Most studies focus on outcomes related to publications, limiting the representation of other types of benefits, such as social impacts or interactions not directly linked to academic production. Therefore, it is crucial to address these intangible results more comprehensively, as they provide a broader perspective on the impact and effectiveness of university–industry collaborations.

It is essential to redefine and more deeply examine the intangible or “less tangible” outcomes of university–industry links. Future research should focus on identifying the benefits that go beyond tangible products, such as opportunities for new projects or the creation of new research areas. It is also crucial to explore negative outcomes, which can provide valuable insights into the transfer process. University–industry links should be evaluated not only for their tangible impact but also by considering the intangible benefits they generate. The lack of attention to industry perspectives on these benefits underscores the need for more in-depth qualitative and quantitative studies that consider the specific sectoral requirements. Only with a comprehensive approach can the current limitations of policies and funding efforts to promote these collaborations be overcome.

Finally, this study has some inherent limitations, mainly related to the constraints of the database used, Scopus. While it is a comprehensive and widely recognized database, it does not cover all research available on UIKT, so readers should exercise caution when generalizing the results. Furthermore, in bibliometric studies, Scopus only analyzes words in the article title, abstract, and keywords, without including a full-text analysis. This limits the depth of the analysis and opens the door for future research that could delve deeper into the study of UIKT. Future investigations could examine the different economic sectors where these studies have been conducted, the differences in methodological approaches (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed), data collection, and key variables used. Additionally, it would be useful to explore the theories employed in UIKT research to identify the dominant theoretical perspectives in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; methodology, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; software, V.A.B.-B.; validation, R.A.Z.-T.; formal analysis, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; investigation, V.A.B.-B.; resources, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; data curation, V.A.B.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T., writing—review and editing, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; supervision, R.A.Z.-T.; project administration, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T.; funding acquisition, V.A.B.-B. and R.A.Z.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was primarily funded by Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores, Grant Number ACS13-060521.

Data Availability Statement

The original data and contributions from this study are provided within the article. For additional information, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by their affiliated institutions in facilitating the research conducted for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Summary of Key Articles

This appendix provides a concise overview of seminal articles that have significantly contributed to the advancement of the field of university-industry knowledge transfer (UIKT). The selected works highlight critical theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and key findings that have shaped the current understanding of UIKT. By presenting these foundational studies, the appendix aims to offer a comprehensive insight into the evolution of the field, as well as the central issues and debates that have emerged over time. This compilation serves as a valuable resource for further scholarly inquiry, shedding light on the ongoing development of UIKT and identifying areas that remain ripe for in-depth exploration.

Table A1.

Overview of Key Articles in the Evolution of UIKT.

Table A1.

Overview of Key Articles in the Evolution of UIKT.

| Document Title | Authors | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university-industry relations (2013) | (Bramwell & Wolfe, 2008) | The article reviews the literature on university–industry relations, focusing on academic engagement as a form of knowledge transfer distinct from commercialization. This includes research collaborations, consultancy, and joint projects, aligning more closely with traditional academic activities. The antecedents and consequences of academic engagement are compared with those of commercialization, highlighting that it is more widely practiced and less driven by financial motives. The study identifies conceptual and methodological gaps and suggests areas for future research on its impact and mechanisms in different contexts. |

| The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities (2013) | (Abreu & Grinevich, 2013) | The article examines academic engagement as a form of academic entrepreneurship that goes beyond traditional activities such as patents and spin-offs. It includes informal and non-commercial activities, such as consultancy, contract research, and public lectures, which generate academic, social, and economic value. Based on data from over 22,000 academics in the United Kingdom, the study identifies individual and institutional factors influencing engagement, such as discipline, prior experience, and institutional support. It emphasizes that a broader perspective on academic engagement enhances knowledge transfer and maximizes the social and economic benefits of universities. |

| The activities of university knowledge transfer offices: towards the third mission in Italy (2016) | (Cesaroni & Piccaluga, 2016) | This study examines the role of knowledge transfer offices (KTOs) in fostering academic engagement and promoting the "third mission" of universities in Italy. Through cluster analysis and multinomial logistic regression, three models of academic engagement are identified: one focused on research, another balancing research and technology transfer, and a third prioritizing social and economic impact. The findings highlight that time, resources, and strategic objectives are key factors in advancing towards a more integrated approach to knowledge transfer, aligning university activities with social and economic development. |

| University research and knowledge transfer: A dynamic view of ambidexterity in british universities (2017) | (Sengupta & Ray, 2017) | This article examines the dynamic interplay between university research and knowledge transfer through the lens of organizational ambidexterity. Leveraging longitudinal data from the United Kingdom, the study reveals that prior research performance significantly enhances knowledge transfer via commercialization and academic engagement. However, this effect is negatively moderated in large or prestigious universities, where the marginal benefits are reduced. Furthermore, knowledge transfer activities, particularly those involving contracts and collaborations, act as catalysts for future research endeavors. The findings underscore the critical need to balance research and knowledge transfer to optimize institutional impact across academic and societal dimensions. |

| Academic engagement as knowledge co-production and implications for impact: Evidence from Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (2017) | (Rossi et al., 2017) | The article highlights academic engagement as a co-production process of knowledge, moving beyond unidirectional transfer. Drawing on evidence from knowledge transfer partnerships in the United Kingdom, it demonstrates that impact relies on sustained interactions among multiple stakeholders and evolves over time, generating both tangible and intangible benefits. This approach fosters conceptual, organizational, and social changes, transcending initial academic boundaries. Furthermore, it presents key implications for assessing academic impact, emphasizing the importance of a narrative that captures the ongoing effect and interdependence inherent in the co-production of knowledge. |

| Knowledge transfer in university–industry research partnerships: a review (2019) | (de Wit-de Vries et al., 2019) | The article reviews practices that facilitate knowledge transfer in research partnerships between universities and industries. It identifies key barriers, such as cultural differences, divergent objectives, and limited absorptive capacity. Additionally, it highlights facilitators like trust, effective communication, and the use of intermediaries. The study argues that knowledge transfer is critical for both theoretical and practical advancements in the field of academic engagement. Furthermore, it offers recommendations for managing these partnerships and suggests avenues for future research, including the exploration of cognitive distances and the integration of academic and industrial perspectives. |

| Academic engagement: A review of the literature 2011–2019 (2021) | (Perkmann et al., 2021) | The article provides a systematic review of the literature on academic engagement from 2011 to 2019, focusing on interactions between academic researchers and external organizations, such as research collaborations, consultancy, and informal connections. It examines the individual, organizational, and institutional antecedents of these practices and their outcomes in terms of scientific productivity, commercialization, and social impact. Additionally, the study identifies recent advancements and unresolved challenges, proposing future research directions related to effects on research quality, academic mobility, and institutional contexts. |

| How academic researchers select collaborative research projects: a choice experiment (2022) | (van Rijnsoever & Hessels, 2021) | The article investigates how academics select collaborative research projects through an experiment involving 3145 researchers from Western Europe and North America. The findings reveal that the opportunity to publish in scientific journals is the most influential factor. It identifies three motivation profiles: “puzzle” (intellectual curiosity), “ribbon” (recognition), and “gold” (financial benefit). Additionally, the study highlights that academics tend to favor academic collaborations over industrial ones. This research underscores the importance of tailored policies to promote university–industry collaborations, respecting individual motivations while fostering both academic development and social relevance. |

| Academics engaging in knowledge transfer and co-creation: Push causation and pull effectuation? (2023) | (De Silva et al., 2023) | The article examines how academics’ motivations and decision-making approaches influence academic engagement, specifically in knowledge transfer and co-creation. Drawing on 68 qualitative interviews, it proposes a conceptual framework integrating resource-based arguments and academic engagement perspectives. The findings highlight how cognitive proximity between academics and firms shapes these dynamics, suggesting that universities should provide tailored training and support to foster effective collaboration. This approach aims to maximize the social and economic benefits derived from university–industry interactions. |

| A bibliometric review of research on academic engagement, 1978–2021 (2024) | (Pham et al., 2024) | The article presents a bibliometric review of the literature on academic engagement from 1978 to 2021, based on data from Scopus. It identifies three phases of growth, with increased attention starting in 2009 and a surge between 2018 and 2021. The leading contributing countries are the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and Germany. Five key themes are highlighted: technology transfer, collaborative research, university–industry relationships, research and development, and entrepreneurial universities. The study emphasizes academic engagement as a driver of innovation and proposes opportunities to strengthen academia–industry collaboration, fostering knowledge exchange and social impact. |

References

- Abbasi, A., Altmann, J., & Hossain, L. (2011). Identifying the effects of co-authorship networks on the performance of scholars: A correlation and regression analysis of performance measures and social network analysis measures. Journal of Informetrics, 5(4), 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42(2), 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. K. (2001). University-to-industry knowledge transfer: Literature review and unanswered questions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(4), 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayici, Y., Coates, P., Koskela, L., Kagioglou, M., Usher, C., & O’Reilly, K. (2011). Technology adoption in the BIM implementation for lean architectural practice. Automation in Construction, 20(2), 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H., Silva, E. R., Lessa, M., Proença, D., Jr., & Bartholo, R. (2022). VOSviewer and Bibliometrix. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(3), 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Phan, P. (2023). Collaboration strategies and SME innovation performance. Journal of Business Research, 164, 114018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeroual, O., & Koltay, T. (2022). RecSys pertaining to research information with collaborative filtering methods: Characteristics and challenges. Publications, 10(2), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, E. C., Sengik, A. R., & Tello-Gamarra, J. (2021). Fifty years of university-industry collaboration: A global bibliometrics overview. Science and Public Policy, 48(2), 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P., Franco, M., Carvalho, A., dos Santos, C. M., Rodrigues, M., Meirinhos, G., & Silva, R. (2022). University-industry cooperation: A peer-reviewed bibliometric analysis. Economies, 10(10), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, B., Fay, D., & Slade, C. P. (2013). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: The-state-of-the-art. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(1), 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, A., & Wolfe, D. A. (2008). Universities and regional economic development: The entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Research Policy, 37(8), 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J., D’Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39(7), 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, U. A., Sayeed, M. S., Razak, S. F. A., Yogarayan, S., Amodu, O. A., & Mahmood, R. A. R. (2023). A method for analyzing text using VOSviewer. MethodsX, 11, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M., Rip, A., & Law, J. (1986). Mapping the dynamics of science and technology: Sociology of science in the real world. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, D., Panizo-LLedot, Á., Bello-Orgaz, G., Gonzalez-Pardo, A., & Cambria, E. (2020). The four dimensions of social network analysis: An overview of research methods, applications, and software tools. Information Fusion, 63, 88–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, F., & Piccaluga, A. (2016). The activities of university knowledge transfer offices: Towards the third mission in Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(4), 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Lockett, A., Van de Velde, E., & Vohora, A. (2005). Spinning out new ventures: A typology of incubation strategies from European research institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 183–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780080517889-chapter3/absorptive-capacity-new-perspective-learning-innovation-wesely-cohen-daniel-levinthal (accessed on 4 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2002). Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L., & Spigarelli, F. (2020). The third mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q. T., Rammal, H. G., & Nguyen, T. Q. (2024). University-industry knowledge collaborations in emerging countries: The outcomes and effectiveness in Vietnam. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 22(6), 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz-Correa, A., Muñoz-Leiva, F., & Bakucz, M. (2018). Past themes and future trends in medical tourism research: A co-word analysis. Tourism Management, 65, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M., Al-Tabbaa, O., & Pinto, J. (2023). Academics engaging in knowledge transfer and co-creation: Push causation and pull effectuation? Research Policy, 52(2), 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36(9), 1295–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit-de Vries, E., Dolfsma, W. A., van der Windt, H. J., & Gerkema, M. P. (2019). Knowledge transfer in university–industry research partnerships: A review. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(4), 1236–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, D., & Shane, S. (2003). Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Research Policy, 32(2), 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Chowdhury, G. G., & Foo, S. (2001). Bibliometric cartography of information retrieval research by using co-word analysis. Information Processing & Management, 37(6), 817–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, S. A. M., Walrave, B., Read, S., & van Stijn, N. (2022). Knowledge transfer to industry: How academic researchers learn to become boundary spanners during academic engagement. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47(5), 1422–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Zhang, Y. Q., & Zhang, H. (2017). Improving the co-word analysis method based on semantic distance. Scientometrics, 111(3), 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J. M., & Carayannis, E. G. (2019). University-industry knowledge transfer—Unpacking the “black box”: An introduction. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 17(4), 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, V. L. S., Stocker, F., & Macau, F. (2023). Knowledge transfer in technological innovation clusters. Innovation & Management Review, 20(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L., & Nieth, L. (2021). The role of universities in regional development strategies: A comparison across actors and policy stages. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(3), 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. (2004). The development of social network analysis. In A study in the sociology of science (Vol. 1). BookSurge, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Gaisch, M., Noemeyer, D., & Aichinger, R. (2019). Third mission activities at austrian universities of applied sciences: Results from an expert survey. Publications, 7(3), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuna, A., & Muscio, A. (2009). The governance of university knowledge transfer: A critical review of the literature. Minerva, 47(1), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., Cunningham, J. A., & Urbano, D. (2015). Economic impact of entrepreneurial universities’ activities: An exploratory study of the United Kingdom. Research Policy, 44(3), 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2012). The development of an entrepreneurial university. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-P., Hu, J.-M., Deng, S.-L., & Liu, Y. (2013). A co-word analysis of library and information science in China. Scientometrics, 97(2), 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfandyari-Moghaddam, A., Saberi, M. K., Tahmasebi-Limoni, S., Mohammadian, S., & Naderbeigi, F. (2023). Global scientific collaboration: A social network analysis and data mining of the co-authorship networks. Journal of Information Science, 49(4), 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klofsten, M., Fayolle, A., Guerrero, M., Mian, S., Urbano, D., & Wright, M. (2019). The entrepreneurial university as driver for economic growth and social change—Key strategic challenges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2015). Co-authorship networks: A review of the literature. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 67(1), 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X. Y., Sun, J., & Bai, B. (2017). Bibliometrics of social media research: A co-citation and co-word analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J., Tomson, G., Lundkvist, I., Sk?r, J., & Brommels, M. (2006). Collaboration uncovered: Exploring the adequacy of measuring university-industry collaboration through co-authorship and funding. Scientometrics, 69(3), 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijan, D., & Sen, S. (2022). Industry–academia research collaboration and knowledge co-creation: Patterns and anti-patterns. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology, 31(3), 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G. D., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2008). Research and technology commercialization. Journal of Management Studies, 45(8), 1401–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V. J. P. D. (2021). Bibliometric analysis for working capital: Identifying gaps, co-authorships and insights from a literature survey. International Journal of Financial Studies, 9(4), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ardila, H., Castro-Rodriguez, Á., & Camacho-Pico, J. (2023). Examining the impact of university-industry collaborations on spin-off creation: Evidence from joint patents. Heliyon, 9(9), e19533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marullo, C., Piccaluga, A., & Cesaroni, F. (2022). From knowledge to impact. An investigation of the commercial outcomes of academic engagement with industry. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 34(9), 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, C., Ferreira, J. J., & Marques, C. (2018). University–industry cooperation: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Science and Public Policy, 45(5), 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourao, P. R., & Martinho, V. D. (2020). Forest entrepreneurship: A bibliometric analysis and a discussion about the co-authorship networks of an emerging scientific field. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscio, A. (2010). What drives the university use of technology transfer offices? Evidence from Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 35(2), 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odei, M. A., & Novak, P. (2023). Determinants of universities’ spin-off creations. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 1279–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, R. (2007). Determinants and consequences of university spin-off activity: A conceptual framework. In Handbook of research on techno-entrepreneurship (Vol. 33, pp. 653–666). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partha, D., & David, P. A. (1994). Toward a new economics of science. Research Policy, 23(5), 487–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M., Salandra, R., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., & Hughes, A. (2021). Academic engagement: A review of the literature 2011-2019. Research Policy, 50(1), 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’este, P., Fini, R., Geuna, A., Grimaldi, R., & Hughes, A. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M., & Walsh, K. (2007). University–industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(4), 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.-H., Ta, T. N., Luong, D.-H., Nguyen, T. T., & Vu, H. M. (2024). A bibliometric review of research on academic engagement, 1978–2021. Industry and Higher Education, 38(3), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, S., Agrahari, A., & Singh, S. N. (2015). Mapping the intellectual structure of scientometrics: A co-word analysis of the journal Scientometrics (2005–2010). Scientometrics, 102(1), 929–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lamorena, Á. J., Del Barrio-García, S., & Alcántara-Pilar, J. M. (2022). A review of three decades of academic research on brand equity: A bibliometric approach using co-word analysis and bibliographic coupling. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Fernández, L. M., Guerrero-Bote, V. P., & Moya-Anegón, F. (2013). Co-word based thematic analysis of renewable energy (1990–2010). Scientometrics, 97(3), 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F., De Silva, M., Pavone, P., Rosli, A., & Yip, N. K. T. (2024). Proximity and impact of university-industry collaborations. A topic detection analysis of impact reports. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 205, 123473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F., Rosli, A., & Yip, N. (2017). Academic engagement as knowledge co-production and implications for impact: Evidence from Knowledge Transfer Partnerships. Journal of Business Research, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F., & Sengupta, A. (2022). Implementing strategic changes in universities’ knowledge exchange profiles: The role and nature of managerial interventions. Journal of Business Research, 144, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F. T., Agung, S. D., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 691–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M. S., & Omar, M. Z. (2013). University-industry collaboration models in Malaysia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 102, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadorinho, J., & Teixeira, L. (2021). Stories told by publications about the relationship between industry 4.0 and lean: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Publications, 9(3), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A., & Ray, A. S. (2017). University research and knowledge transfer: A dynamic view of ambidexterity in british universities. Research Policy, 46(5), 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., Hu, Z., Luo, M., Huo, T., & Zhao, Q. (2021). What is the policy focus for tourism recovery after the outbreak of COVID-19? A co-word analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D. A., Atwater, L. E., & Link, A. N. (2003). Commercial knowledge transfers from universities to firms: Improving the effectiveness of university–industry collaboration. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 14(1), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skute, I., Zalewska-Kurek, K., Hatak, I., & de Weerd-Nederhof, P. (2019). Mapping the field: A bibliometric analysis of the literature on university–industry collaborations. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(3), 916–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]