Abstract

The ability to conduct an explicit and robust literature review by students, scholars or scientists is critical in producing excellent journal articles, academic theses, academic dissertations or working papers. A literature review is an evaluation of existing research works on a specific academic topic, theme or subject to identify gaps and propose future research agenda. Many postgraduate students in higher education institutions lack the necessary skills and understanding to conduct in-depth literature reviews. This may lead to the presentation of incorrect, false or biased inferences in their theses or dissertations. This study offers scientific knowledge on how literature reviews in different fields of study could be conducted to mitigate against biased inferences such as unscientific analogies and baseless recommendations. The literature review is presented as a process that involves several activities including searching, identifying, reading, summarising, compiling, analysing, interpreting and referencing. We hope this article serves as reference material to improve the academic rigour in the literature review chapters of postgraduate students’ theses or dissertations. This article prompts established scholars to explore more innovative ways through which scientific literature reviews can be conducted to identify gaps (empirical, knowledge, theoretical, methodological, application and population gap) and propose a future research agenda.

1. Introduction

Most academic writings require a critique of prior and relevant body of writings (publications) as an essential holistic feature on a specific subject matter [1,2]. This sort of literary enquiry is critical in academic writing to ensure that existing knowledge is discussed to grasp their convergences and divergencies logically [2]. It is also necessary to uncover gaps that exist in a specific area of knowledge, as well as to explore the knowledge needed to make progress in that area of knowledge [3]. This type of writing is crucial to curate—i.e., by building, generating and disseminating—knowledge as part of an in-situ (part of a section) or ex-situ (standalone) writing project. In whichever way or form it is completed, it is always meant to create “a firm foundation for advancing knowledge” within a literary work or academic writing [1]. That is why it is technically referred to by scholars as a “literature review” [4,5].

An explicit literature review is an integral part of scientific communication, which is almost mandatory in certain writing projects [6,7]. They are critical in journal articles, academic theses, academic dissertations, working papers or other forms of reports written by and for scientists. Students in postgraduate programmes in higher education institutions must have the necessary skills and understand the techniques for conducting scientific literature reviews [8]. Unfortunately, not many have the skills or understanding to conduct a thorough literature review. A lack of necessary knowledge for conducting literature reviews may lead to the presentation of incorrect, false or biased inferences [9]. Accordingly, sound scientific knowledge on literature in specific fields of study should be inculcated to mitigate against biased inferences such as unscientific analogies and baseless recommendations. The consequence is that many scholarly writings are fraught with problems caused by a poor review of literature. Some scholars have highlighted eight common problems with conducting an appropriate literature review [2,10]. These include issues related to the relevance of the subject, methods (search, identification, selection, synthesis, and analysis) and writing 10. Poor literature skills and knowledge are a big concern in higher education institutions around the world. In these institutions, students at all levels (undergraduate, postgraduate and doctoral levels) require skills to locate, synthesise and present literature in logically argued and written forms as part of their theses or dissertation writing. Where literature is overlooked by these emerging or early career scholars, it could lead to complexities in obtaining high-quality data for their academic reports and journal articles. This is even more challenging given the scarcity of academic guides on the quality of literature reviews and how to conduct them [3]. This is a gap this study hopes to contribute to.

This study is designed to provide a basic understanding of literature review—including an understanding of the skills and techniques—and how to conduct one. The narrative presented in this study is aimed at postgraduate students that are eager to apply them in their scientific writing and research projects. The idea behind addressing the “how-to” aspect of the literature review is not to replicate the traditional approach [11] to reviewing literature or endorse a systematic approach [12]. The literature review perspective presented in this study is meant to serve as a guide to those who are eager to explore the approaches to conduct scientific literature reviews. It is also hoped that this article will raise further awareness on the application of literature review in scientific paper writing.

The study is structured into five sections, with each section detailing a particular aspect of the literature review. The first section (this current section) helps to define the objective of the study. The next section (Section 2) answers the question of what a literature review is. It is hoped that this section will enable readers to understand what it is not. This is followed (Section 3) by an exploration of the how-to aspect of the literature review (including searching, identifying, selecting, and synthesising contents). The article further addresses the problems and solutions for a better literature review (Section 4), and then draws conclusion (Section 5).

2. Making Sense of a Literature Review: What It Is All About

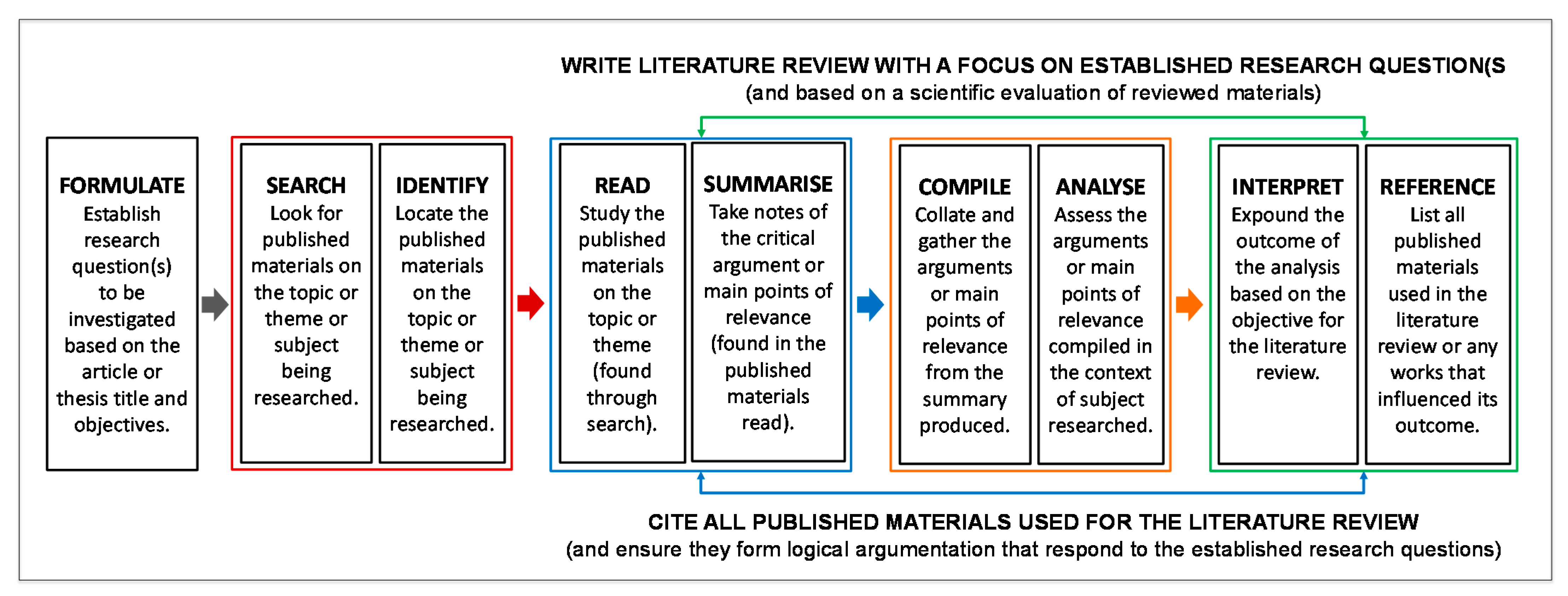

A literature review is an evaluation of research works available on a specific academic theme or topic or subject under investigation by a researcher. It involves a process of investigating already written and published bodies of writing to achieve specific research objectives other than those already achieved by the works under investigation. Based on our definition of literature review in this paper, a literature review can be viewed as a literature investigation. This sort of investigation (that is, the literature review process) involves several activities. Each of these activities (which constitute sub-processes) is further explained with Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Activities in a literature review process (authors’ illustration).

Figure 1 shows the literature review as a process that involves several activities including searching, identifying, reading, summarising, compiling, analysing, interpreting, writing (including citing based on a prior established research question) and referencing. In whatever way a literature review is conducted, it is expected to be scientific in its objective, process, structure and output. What can make it scientific is that it must follow a systematic pattern of argumentation. It must focus on the main points of scientific arguments relevant to known research. It must examine the structure of the research and interpret such research through the lens of the field of the researcher. Its evaluative approach must be based on known and established criteria chosen, stated and explained by the researcher doing the review. While conducting the review, the researcher must also use evidence to support findings and opinions derived from the evaluation of others’ scholarly works.

No matter how a literature review is conducted, it will involve writing and citing what has been found while reading, summarising, compiling, analysing and interpreting the findings from previous studies and making a case for future research agenda. This makes the writing and citing aspect of the literature review overarching activities. Together, they form a continuum of scientific procedures that are carried out throughout the entire literature review process.

A literature review is an important part of knowledge generation and dissemination in all academic disciplines. However, it is different from simply literature (a term usually used for the study of works in the literature discipline). In the academic disciplines (that is, literature as an academic discipline), literature may refer to poems, novels and plays. However, in the generic academic environment (the platform from where we are writing this article), when we say “literature review” or refer to the ‘literature’, we are talking about the research (scholarship) in a given field” [7]. Where a literature review is conducted in the form presented in Figure 1, it can lead to two potential outputs—as a full written output or a concrete section or part of a broader written academic document.

2.1. Literature Review as a Concrete Document or Standalone Writing Output

A literature review can be structured in the form of a document or schema that depends on key relevant sources on a topic and discussions that reflect the sources in conversational or narrative format to improve knowledge on the subject being researched. Literature review as a standalone scholarly work (writing output) could be referred to as desktop or secondary research since it has to do with reading, summarising, compiling, analysing and interpreting published materials in a specific research domain [13]. For example, a desk-based review of existing literature or data can be conducted following a qualitative [14], quantitative [15] or mixed methods approach [16,17]. The output can be presented in the form of a scholarly or professional report, usually called a review article. In this case, the literature review takes the format of a report or document that is based on a survey of scholarly/professional knowledge on a specific/general subject/topic. Such a report is normally common in academia or industry and is produced to reflect a broad range of scholarly debates, positions or working papers. It can also offer in-depth engagement in discourse to produce, critique, stimulate or promote ideas on a specific subject [18,19]. This sort of literature output is commonly referred to as review articles (in scholarly journals) or review reports (in the industry). In the industry, a standalone literature review (as a full report or document) can be produced as a means of ascertaining a state of the art (or science) of a subject. When written as a standalone piece, a literature document will have its own components for introduction, body and conclusion. It can also be produced as an integral part of a broader investigation on subjects related to specific academic or industry concerns.

2.2. Literature Review as a Section of a Scientific Paper or Document

A literature review can also take the form of a section of a document which reports a research output (e.g., a research article). When written as a non-standalone piece, the literature document will not have its own components for introduction, body and conclusion. Instead, it would be part of the body of the article or paper. In this scenario, the literature review can serve as a specific section of an article that critically reviews (and informatively synthesises scholarly publications on a specific research topic) to frame a path of theory, argument or evidence in that article [20]. Literature can also be applied as a methodological approach within an article in which the overall objective is not to review literature. This is possible when the data used in the article are collected through a process of literature review. Where this is the case, a literature review must be identified and presented as the methodology of the study [21].

Just as diagramming is fundamentally considered as the visual language in research [5], literature review serves primarily as the textual language for communicating a major aspect of a research paper, thesis, working paper or any scientific document [22]. Irrespective of the nature of a literature review, completed within broader scientific writing, it takes the form of a critical discourse of ideological, theoretical, statistical and conceptual publications that are of specific or general relevance to the scholarly discipline, subject and topic of the research, as well as other forms of professional enquiry [2,11,14,20]. In academic/professional writing, a literature review can demonstrate a researcher’s awareness of the wide range of research (in terms of methodology and theory) related to the proposed research subject/topic. It provides evidence of a deep understanding of already published research related to a subject. It can also be used to identify novelties and gaps in already published scholarly works [23]. By exploring novelties and gaps, literature reviews can serve as a means of establishing originality for existing research or simply emphasise originality in scientific writing.

2.3. Some Notable Literature Review Approaches

There is no conventional way of conducting a literature review since the research questions can influence its methodology or approach. This is where the knowledge of some notable literature review approaches is essential for emerging or early career scholars [1,7,24,25]. Depending on the methodology needed to achieve the purpose of the review, the knowledge of the different literature review types can help adopt the most appropriate approach to meet specific objectives [3]. These approaches can be qualitative, quantitative or have a mixed method approach depending on the phase of the review. Table 1 presents the notable types of literature reviews applicable in most everyday scientific writings [3,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Table 1.

Summary of literature review types, focus, and their applicable disciplines (authors’ compilation).

There is a continuum of literature types [29]. Hence, only the broad types have been presented in this article. It is possible that the types presented here may require various forms of adaptation when used by certain researchers from different disciplines. They can also be hybridised to create more convenience for easier or more suitable applicability within disciplines or between researchers. Also important is that, depending on the researcher or scientist, many elements from these different types of literature reviews may be combined to achieve a specific methodological purpose. Irrespective of how these are combined, it is important to understand the typical description of the tabulated types of literature reviews in detail.

The narrative literature review is sometimes called a traditional literature review. It focuses on producing a critical, comprehensive analysis of the current state-of-the-art (or science) on a given topic/subject. It is an everyday part of scientific writing because it is essential when establishing a theoretical framework or focusing on contexts [33]. A systematic literature review involves a rigorous approach to reviewing the literature [12,20]. This type of review is much more structured than many other literatures review types. It is applied methodologically for answering specific research questions [21]. An integrative literature review builds new knowledge based on the existing body of literature following a deductive logical reasoning and rationalist perspective [16,17]. It can be either concept-centric (focusing on reviewing and building new concepts) [34], constructivist (creating new knowledge rather than just passively exploring information) or theoretical (focusing on reviewing and building new theories) in focus.

Meta-analysis literature review involves investigating the outputs (or findings) from selected scholarly publications and analysing them through standardised statistical procedures [15,35]. Methodologically, it is useful for drawing conclusions and patterns between published findings. A bibliometric review is a scientific approach to literature review targeted at analysing bibliographic material in a quantitative fashion to identify the trends of prior studies on a specific subject, topic or discipline [36]. Scopus and Web of Science databases are instrumental in conducting bibliometric analyses of existing literature in different disciplines to establish trends on the development and application of knowledge on specific subjects and disciplines. Whereas the meta-synthesis literature review, in most cases, evaluates and analyses findings from qualitative studies and aims to build on previously conceptualised and interpreted works from the literature [14]. It is important to acknowledge that a literature review can also be interpretative. The interpretative review is based on interpreting what other scholars have written to present a clearer view of the literature under investigation. The focus here is primarily to interpret what is available in the literature about a subject that is either considered ambiguous or unclear.

3. Searching, Identifying, Selecting, and Synthesising Contents of Existing Literature

All the literature review types identified in this article have one thing in common—they explore what other people have written. They can identify what is known (or unknown) in the subject area, identify areas of controversy or debate, and help formulate questions that need further research [4]. They can be applied in various practical ways, including in primary research projects; reviews written as an introduction and foundation for a research study, such as a thesis or dissertation; and reviews as secondary data analysis research projects [24]. Regardless of the type, a good literature review is characterised by the author’s efforts to evaluate and critically analyse the relevant work in the field. Published reviews can be invaluable because they collect and disseminate evidence from diverse sources and disciplines to inform professional practice on a particular topic. This directed reading will introduce the postgraduate student (as an emerging or early career scholar) to the process of conducting and writing their literature review. However, doing this requires various other structured activities, including the “how-to” aspect of searching, identifying, selecting and synthesising the literature contents.

3.1. Searching for Literature

The literature search is a fundamental step in conducting credible research [37]. It involves systematic and thorough scouting to identify all types of published works relevant to a specific topic or subject under investigation [12,36]. Literature search can also be viewed as an organised foraging for published works in a well-structured and efficient way to locate scholarly evidence on the subject in books, journals, organisational/government documents and the internet. The search can be performed in a brick-and-mortar library using library cards or computers and with the help of a professional librarian. However, most literature searches are currently completed online using the internet through web search engines [38]. The focus of this article is on internet-based literature searches because they have become a fundamental element in research and can influence the methodology and outputs of any research process.

There are several ways of searching for relevant literature. A search can be performed using Google or Google Scholar search engines. While Google search engines are suitable for finding the most relevant source for your research question, the use of scientific or organisational repositories can produce better results in specific situations.

A search term is called keywords in the literature search. Search terms or keywords are subject-specific or topic-specific words which are used uniquely as a point of access (or search queries) to broader published materials. Scientific repositories offer literature search operations in a structured way by allowing researchers to use keywords and single or multiple filters that enable ease of access to literature. Examples of some common scientific repositories are Clarivates (also known as Web of Science or WoS), ScienceDirect, Springer and the Directory of Open Access Journals. Other publisher-based repositories include CABI, MDPI, Springer, Taylor and Francis, Wiley, Sage, Geobase and JSTOR, among many others. For example, Scopus and Web of Science databases have been proven useful in conducting bibliometric analyses of existing literature in various research domains to establish trends [38,39,40,41].

Organisational repositories are great for accessing institutional publications or grey literature (that is, non-journal-based published works). Examples of such repositories are set up by organisations such as the United Nations, European Union, African Union and global and national professional organisations.

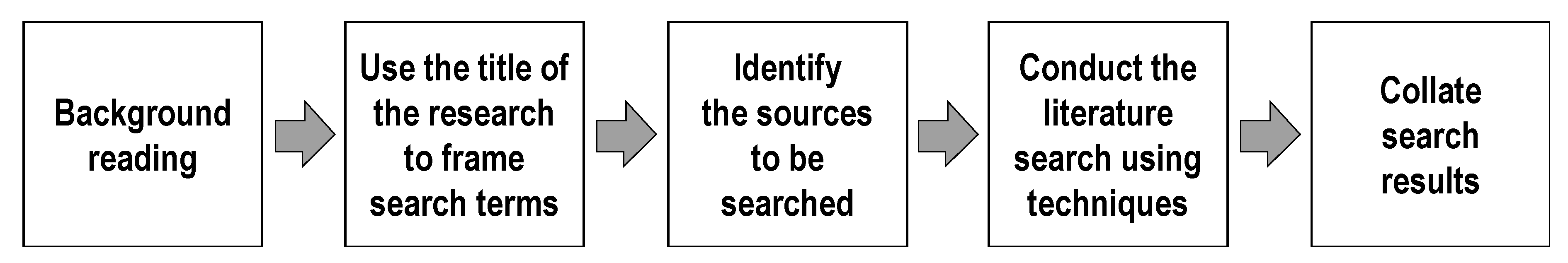

No matter how a literature search is completed, it will involve five generic activities. These include starting with background reading, to framing of the relevant search terms, to identifying the resources to be searched, to conducting the actual search and ends with collating the results from the search (Figure 2). These steps may not necessarily follow a linear process. However, they usually start with a background reading and conclude with the collation of the search results.

Figure 2.

Activities in a literature search process (authors’ illustration).

3.2. Types of Literature Search

There are various ways to conduct a literature search. What matters is to achieve the objective of the search, which is to obtain a representative number of appropriate references for conducting a thorough literature review. Whether a reference is appropriate will depend on the focus of the study and specific research questions or objectives. However, it is important to know when to be specific or broad. For instance, a researcher can specify the search criteria as narrow as possible to obtain the relevant results or as broad as possible to obtain significant results.

The starting point of a literature search includes the use of keywords in web search engines for electronic resources, reference lists, research papers, lecture notes, textbooks, review papers and other forms of academic and grey publications [42]. The researcher’s understanding is important in carrying out an efficient search because not all literature sources will be relevant to the study being conducted. It may be necessary to rely on various kinds of literature sources for research (including scientific or professional literature, background and reference literature). A lack of understanding of the subject by a researcher will affect the quality of documents collected for review.

Table 2 shows the typical sources for accessing published scientific information during a literature search. Again, the onus is on a researcher to identify the novelty of any articles during the search and determine what is necessary or unnecessary for the research being conducted. The actual search for relevant forms of literature can be sourced from any credible databases. The form of literature adopted from each database by the researcher will depend on the need and scope of the work to be performed. Some key forms are identified as follows:

- Theme-centric literature search: This search is based on broad themes instead of specific or narrowed concepts. Such a search is bound to produce broad thematic outputs which the researcher must further process to identify specific articles suitable for the research being performed.

- Concept-centric literature search: The focus of this form of search is on the main concepts related to the subject. Put simply, it entails searches using the concepts as keywords.

- Approach-centric literature search: This form of searching the literature is performed according to specific methodological approaches relevant to the research being conducted.

- Author-centric literature search: This involves searching with a focus on the citations or specific authors. This is possible if the researcher knows influential or authoritative authors on a particular subject. This allows searching for specific authors to pull out their publications to ascertain suitable or unsuitable literature for the subject under investigation.

- Journal-centric literature search: This search is based on identifying articles published by a specific journal. It leads to broad outputs but can be necessary while applying broad filtering as part of the search process. It will lead to producing only articles published by a specific journal.

- Period-centric: Thousands of articles are published yearly on a subject. This form of search focuses on the years of publication considered relevant by the researcher. It is based on filtering published materials based on the year of publication (for example, from the last 2 to 5 years). This approach is highly relevant when searching within a subject-focused database.

Table 2.

Sources of published scientific information for a literature search.

Table 2.

Sources of published scientific information for a literature search.

| Literature Search Sources | Focus |

|---|---|

| Research articles | Focused on the original investigation on specific scientific subjects/themes and are expected to produce innovative or new contributions to the subject being investigated. |

| Review articles | Usually published in journals, which in most cases, survey the state-of-the-art in a particular field. |

| Edited proceedings | The volume of articles presented at a congress or conference that is compiled into a volume and edited by an editor or group of editors. |

| Edited books | The books published by several chapter contributors but edited by an editor or group of editors. |

| Books or book chapters | Specific chapter contributions in edited books. |

| Conference papers | Presented at workshops, congresses, conferences or other forms of scientific fora. |

| Theses | Academic dissertations published or unpublished in lieu of graduation from a university or research institution. |

| Textbooks | Specialist books published on specific academic subjects for classroom teaching. |

| Online/electronic based articles | Published materials on academic or professional websites that are available in digital form. |

| Newspaper/magazine articles | Articles that tackle scientific or professional subjects and are published in national newspapers or magazines. |

| Technical reports | Institutional publications that may be useful for accessing primary data, graphs, maps and figures relevant to a project, topic or subject of research interest. |

| Preprints | Preprints are pre-publication versions of scientific papers made accessible to the public before its formal peer review and publication in a scientific journal. |

| Scientific posters | Posters are a method of presenting scientific findings in conferences through a combination of texts, images, figures and graphics. They serve as hybrid means of scientific communication between an oral presentation and a manuscript. |

3.3. Literature Search Techniques

There is no specific technique or strategy for literature search. Each researcher is expected to adopt an approach that best suits them. However, there are generic techniques that could help a student or an early career scholar (who has not developed specific techniques). Such techniques to consider during the literature search could include:

- Manual searching approach: This technique involves surveying tables of contents in relevant key journals manually (in brick-and-mortar libraries) or in hard-copy materials within a physical environment such as an office. It helps in identifying relevant materials which can be further subjected to rigorous physical or desktop search.

- Citation searching (or cited reference searching) approach: This is an approach that is based on searching for articles that have been cited by other publications. It can be used to “find out whether articles have been cited by other authors, find more recent papers on the same or similar subject, discover how a known idea or innovation has been confirmed, applied, improved, extended or corrected” [43]. It is possible to apply this kind of search on repositories or databases such as OvidSP, Scopus, Web of Science or Google Scholar, among many others.

- Theme searching approach: A theme-based search involving the use of subject headings is crucial in a literature search. Using appropriate subject headings can enhance the literature search and will help a researcher to find more results on a topic/subject. This is because subject headings find articles according to their subject.

- Spider searching approach: This involves identifying specific relevant publications applicable to your research. A further search is performed based on what has been identified to gain additional information. For instance, if the researcher identified a publication that has been cited, a further search could be completed by consulting the reference list of that publication to know more about other works of that cited author. This is called a “backwards spider” approach [43,44,45]. The backward spider approach is very common because most literature review processes involve reading through cited paragraphs and identifying listed references to trace (backwardly). Another type of spider approach is when a researcher reads a publication by a particular author and decided to search for other publications written by that same author. This is called a “forwards spider” approach [46]. It can also take the form of an author reading a particular publication which motivates that researcher to search for other related articles linked to the previous one. This is described as a “sideways spider” approach [47]. This article does not promote any approach. A combination of search approaches is usually more effective.

- Truncation and wildcard searching approach: This involves the use of truncated and wildcard searches to find variations to widen or reduce the scope of searches. Truncation allows for finding singular and plural terms or keywords with variant endings. Applying truncations and wildcards is easy when using Boolean logic to combine search terms. Boolean logic is a form of algebra which is centred around three simple words known as Boolean operators (that is, AND, OR and NOT) [48]. Boolean operators can be used for different combinations of search terms or keywords. Using a wildcard allows for finding variant spellings of search terms and keywords. For instance, applying wildcards are important for finding American and British spellings. In general, truncations and wildcards can take the following formats (with varying influences on the output of a search):

- -

- Linking keywords: Entering more than one keyword in a search engine can link those words with other connecting words. This can be completed with the use of AND, OR and NOT. The use of AND or OR or NOT can have different effects on a search. Linking keywords with AND will narrow your search, retrieving only results containing both terms. Linking keywords with OR will broaden your search, finding results that contain either or both terms. Put differently, OR is used to find articles that mention either of the keywords being searched; AND is used to find articles that mention both searched keywords; NOT is used to exclude a keyword or concept from the search.

- -

- Asterisking keyword endings: Inserting an asterisk (*) at the word-ending of a keyword will automatically produce a search result for all the possible endings for that word. Many databases use an asterisk (*) as their truncation symbol. It is necessary that researchers apply specific truncations in their search. For example, “therap*” will find therapy, therapies, therapist or therapists [49].

- -

- Using variant spellings: Using OR to capture variant spellings (e.g., neighbour OR neighbor) will lead to searching for the variant keywords inclusively.

- -

- Exacting phrases: Enclosing terms in quotation marks (“”) will lead to a search for that specific term or quote.

3.4. Identifying and Selecting the Literature Materials

After a literature search has produced results, which would normally be a volume of publications, it is important to identify and select the relevant ones. Electronically, this can be completed through a process of filtering when using online databases. However, it would always require hands-on identification and selection to pick the actual materials to be fully read and then synthesised as part of the literature review process [3]. Table 3 depicts a typical evaluation template for identifying and reviewing literature to highlight the importance, relevance, contrasts and similarities of the reviewed published materials. This will provide a holistic assessment of the quality of the literature and will assist in establishing whether the identified research gaps have been addressed.

Table 3.

An evaluation of the reviewed published material for the literature review.

The identification and selection of relevant literature can be completed through a rapid assessment of literature quality. There are different metrics to select published materials based on their quality. These include the authors, citation counts, the quality of journals or platform of publication, and the relevance of the subject of the publication to the topic/subject to be reviewed [50]. Journal quality can be based on Impact Factor (IF) rankings. The IF is a measure of the frequency with which the average article in a journal has been cited in a particular year [51]. It is used to measure the importance or rank of a journal by calculating the times its articles are cited.

The Hirsch index or Hirsch number (usually referred to as the h-index) 52 is a metric for selecting an author’s work for review. It is an author-level metric that measures both the productivity and citation impact of the publications of an author [52,53] and is based on both the number of papers published and the number of citations those papers have received [54] The h-index of authors can help a researcher determine whether the author is respected in their discipline and regarded as an authority on the subject being reviewed.

3.5. Reading and Synthesising Content

Scholarly articles (or research papers) are different from other types of written publications. A scholarly work is expected to produce a result of original research performed, along with a claim for novelty and significance. Depending on the discipline, ideological bases or methodologies used [55], the ease of comprehension of research articles can vary. However, a good scientific article is expected to provide a comprehensive and clear message. Slow and focused reading may be required for overall comprehension of research articles. In some cases, speed reading may be necessary. Irrespective of how it is read, what matters is to understand the thesis statement of the article and study its argumentation, methods, results, and conclusions [56]. After reading, the next stage would be to synthesise (or summary analysis) what has been understood for integration into a broader writeup leading to a literature review output.

The content of the article could be manually thematically analysed to draw up a synthesis of key elements of the article that would be relevant in a proposed review article or literature review exercise. It can also be analysed with the use of software tools that can enable quick textual analysis (i.e., text-based analysis) from whence an informed synthesis can be drawn [57]. Both manual and software analysis have proven to be effective. Software usage can produce more details. Some software tools that support the analysis of text resources for literature review purposes include NVivo, PRISMA, Leximancer and a few others. NVivo can be used for importing and analysing text-based data [58]. It can also enable the coding, notetaking, arrangement and annotation of articles. PRISMA (meaning: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) allows for reporting systematic reviews of published materials [59]. It has a function for conducting a checklist and flowchart of systematic literature review. Leximancer has a fully automated environment for coding and quantifying literature resources [59,60,61]. It can be used to examine a body of texts and produce a ranked list of keywords based on frequency and occurrence. These can allow a researcher to visually represent and show linkages between concepts while producing a synthesised output of read documents.

3.6. Analysing Research Gaps in the Literature

Beyond reading and synthesising the content of existing knowledge (literature) within a research domain, a scholarly work is expected to examine the gaps in literature. The essence of conducting a literature is to strengthen and deepen the knowledgebase on the subject under investigation. Postgraduate students and early careers often ignore the basis of scientific literature reviews in their scholarly works for a lack of know-how and skill. They usually conduct a literature survey rather than the required literature review. A thorough literature review gears towards a critical evaluation of the material or content related to a specific subject, topic or research question with the purpose of identifying a gap and/or closing the gap identified. A research gap as a missing link or lacuna found in the literature, which should be addressed through innovative review. The research gaps can be classified into seven types, namely empirical gap, knowledge gap, evidence gap, theoretical gap, population gap, application or implementation gap, and methodology gap [62,63]. The ability to identify and address these gaps in scientific literature review usually pave ways for new and innovative research.

An empirical gap arises when the material or publications on a specific subject, topic or research domain provided some claims without empirical evidence to support such claims [64]. The need to provide empirical verification of such claims through collection of quantitative or qualitive data will pave ways for further research. An empirical gap on a topic or subject can be addressed by conducting a quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods research to verify such claims. A knowledge gap could be identified through a systematic literature review [65]. The knowledge gap is identified in the content of exist literature on a specific topic when it fails to provide clarity on the concept and/or application of such concept or phenomenon. Further research can be conducted to provide the required conceptual clarification in such grey areas of research. For example, a phenomenological research could be conducted to address the practical-knowledge gap [62] identified by collecting in-depth information from practitioners to explain why practice deviates from the literature [66].

An evidence gap occurs when new research finding contradicts widely accepted conclusion on a specific subject, topic or research domain [63]. It offers a provocative exception to prior research in a specific field. Such contradictory evidence may suggest the need to embark on mixed methods research to address the gap identified. The theoretical gap “is the type of gap that deals with the gaps in theory with the prior research” [64], (p. 4). A lack of theoretical knowledge or framework on a subject or topic could be referred to as a theoretical gap, suggesting the need to conduct a grounded theory to develop a new theory or borrow theories from other disciplines and applied in another for theoretical triangulation [67,68].

A population gap is the type of gap identified through reviews of prior studies on a specific subject, topic or research domain. The population gap is established based on a thorough analysis of prior studies revealing that some sub-populations were unexplored or under-researched [64]. Identification of such gaps may suggest the need to conduct research within the context of some specific sub-populations (e.g., developing countries or global south). Empirical studies could be conducted to address such gaps by collecting data (quantitative or qualitative) from the specific sub-populations and conducting a robust data analysis procedure to report the findings. The application or implementation gap is otherwise known as a research-implementation gap [69] or practical-knowledge gap [64]. The research-implementation gap “occurs when there is a mismatch between what practitioners know and what can be known from the existing evidence” [69], (p. 3). The research-implementation gap can be addressed via a phenomenological study targeted at gathering in-depth information from practitioners to juxtapose how practice deviates from the literature.

A methodological gap can be identified through a systematic review of research methods adopted by prior studies conducted on a specific subject, topic or phenomenon under investigation. Research addressing methodological gaps are useful in showcasing the influence of methodology on research outcomes or findings [62,63,64]. Mixed methods research can be conducted to explain the predictive influence of explanatory variables on an endogenous variable, and simultaneously providing an in-depth analysis geared towards exploring the perception or experience of participants concerning the constructs under investigation by way of in-depth interviews. A multi-method research [70] can be conducted to address such gaps and establish methodological triangulation [71].

4. Typical Problems and Solutions for Better Literature Review

Literature reviews are an integral part of communication in scientific writing. Hence, every scientist would encounter it in their writing. However, many literature reviews fall short of the required standards [72]. The consequence is that such reviews end up presenting incorrect or biased conclusions [10]. This is commonly witnessed in academic theses, where both undergraduate and graduate students struggle in reviewing the literature to produce an objective conclusion on a subject/topic. Many scholars have dedicated efforts to identify some common problems with badly articulated and written literature reviews [10,25,48,72]. Since the objective of this article is partly to ensure that a broadened understanding of a literature review is disseminated to those who may be struggling on this subject, it is imperative to identify the common challenges students face and their relevant practical solutions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Common problems with conducting a literature review and ways to mitigate them.

The above-mentioned challenges are not exhaustive. Other challenges that students face, which let their literature review writing skills down, exist (even with knowing how to do a good literature review). In all cases, it is important that researchers scout information carefully, identify research gaps and do an accurate selection of literature. These are preconditions to doing a better analysed or synthesised literature review.

5. Conclusions

Over the past decades, a continuum of students and researchers have been requiring opportunities to develop an effective literature review [32]. These emerging and early career scholars face challenges because there is a lack of awareness and appreciation of the methods needed to ensure appropriate literature reviews [2,10,72,73,74,75]. This study offers insights on how a thorough literature review can be conducted to produce either standalone or non-standalone scientific writing. This article has identified critical literature review steps that will give postgraduate students and emerging scholars choices in their approach to conducting appropriate literature reviews. The article is important in ensuring that literature reviews are free from bias and produce valid reliable evidence as an essential component of both scholarly and professional writing. This article was written to encourage authors to conduct more rigorous literature reviews. This also means that all scholars (students, academic/professional writers, editors and peer-reviewers) should improve their literature review writing skills. This article holds that knowledge is not static; we need to explore more innovative ways in which in-depth literature reviews can be conducted to identify research gaps and embark on scholarly work or propose future research agenda. Therefore, a thorough literature review can be conducted following the scientific processes outlined and explained in this article. We hope this serves as reference material to improve the academic rigour in the literature review chapters of postgraduate students’ theses or dissertations.

This research has provided a generic approach to scientific literature reviews, which can be followed by postgraduate students and early careers in evaluating prior research conducted on specific subject or topic for proper conceptualisation and operationalisation of their studies. Future research could be conducted to offer a discipline-specific literature review following the scientific approach. It is hoped that future research can address discipline-specific issues in crafting or writing literature reviews on a particular subject or topic. For example, such studies could be structured to address literature review issues in humanities, arts, social sciences, natural sciences, management sciences, health sciences, pure sciences, computing and informatics, spatial sciences, engineering and professional practice or consulting. The study has been completed on the premise that some scholars can learn the art and science of literature review from a general-to-specific knowledge paradigm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.E.C.; methodology, U.E.C. and S.O.A.; software, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; validation, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; formal analysis, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; investigation, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; resources, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; data curation, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; writing—review and editing, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; visualization, U.E.C. and C.C.D.P.; supervision, U.E.C. and S.O.A.; project administration, U.E.C., S.O.A. and C.C.D.P.; funding acquisition, U.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our students at the Namibia University of Science and Technology. It was their questions during classes that motivated us to engage in this study. We hope it would be helpful to all students and early career scholars who are seeking more comprehensive, and yet condensed, information on how best to conduct a literature review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. MIS Q. 2002, 26, xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Pautasso, M. The Structure and Conduct of a Narrative Literature Review. In A Guide to the Scientific Career: Virtues, Communication, Research and Academic Writing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderston, A. Writing an Effective Literature Review. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2008, 39, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E. Visually Hypothesising in Scientific Paper Writing: Confirming and Refuting Qualitative Research Hypotheses Using Diagrams. Publications 2019, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, J.L.; Galvan, M.C. Writing Literature Reviews: A Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, C. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Research Imagination; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C. A Guide to Conducting a Standalone Systematic Literature Review. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agin, S.; Karlsson, M. Mapping the Field of Climate Change Communication 1993–2018: Geographically Biased, Theoretically Narrow, and Methodologically Limited. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Bethel, A.; Dicks, L.V.; Koricheva, J.; Macura, B.; Petrokofsky, G.; Pullin, A.S.; Savilaakso, S.; Stewart, G.B. Eight Problems with Literature Reviews and How to Fix Them. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesson, J.; Matheson, L.; Lacey, F.M. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, A.; Aranda, Z.; Colbourn, T.; Agwai, I.C.; Bahiru, S.; Bakare, A.A.; Burgess, R.A.; Cassar, C.; Shittu, F.; Graham, H. The Burden and Risks of Pediatric Pneumonia in Nigeria: A Desk-based Review of Existing Literature and Data. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, S10–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Using the Past and Present to Explore the Future. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2016, 15, 404–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P.; Gillett, R. How to Do a Meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2010, 63, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witell, L.; Snyder, H.; Gustafsson, A.; Fombelle, P.; Kristensson, P. Defining Service Innovation: A Review and Synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.M.; Van Regenmortel, T.; Vanhaecht, K.; Sermeus, W.; Van Hecke, A. Patient Empowerment, Patient Participation and Patient-Centeredness in Hospital Care: A Concept Analysis Based on a Literature Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1923–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An Analysis of Definitions, Strategy Steps, and Tools through a Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological Quality of Case Series Studies: An Introduction to the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.S.C. The Schematic Structure of Literature Reviews in Doctoral Theses of Applied Linguistics. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2006, 25, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Human Resource Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boote, D.N.; Beile, P. Scholars before Researchers: On the Centrality of the Dissertation Literature Review in Research Preparation. Educ. Res. 2005, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Dowling, N.M. Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review of the Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008, 78, 367–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-narrative Reviews. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodell, J.B.; Breitsohl, H.; Schröder, M.; Keating, D.J. Employee Volunteering: A Review and Framework for Future Research. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antons, D.; Breidbach, C.F. Big Data, Big Insights? Advancing Service Innovation and Design with Machine Learning. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Houston, M.B.; Hulland, J. Review Articles: Purpose, Process, and Structure. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.; Rich, M. The Challenges of Writing an Effective Literature Review for Students and New Researchers of Business. In Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2–3 June 2022; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, B.K.; Solarino, A.M. Ownership of Corporations: A Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1282–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, L.; Vaca, S. Refining Theories of Change. Evaluation 2018, 14, 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, M.; Cronin, P.; Ryan, F. Step-by-Step Guide to Critiquing Research. Part 1: Quantitative Research. Br. J. Nurs. 2007, 16, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigó, J.M.; Blanco-Mesa, F.; Gil-Lafuente, A.M.; Yager, R.R. Thirty Years of the International Journal of Intelligent Systems: A Bibliometric Review. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2017, 32, 526–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, A.; Kataria, H.; Dhawan, I. Literature Search for Research Planning and Identification of Research Problem. Indian J. Anaesth. 2016, 60, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, M.J. Making Sense of Credibility on the Web: Models for Evaluating Online Information and Recommendations for Future Research. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 2078–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasko, O.; Chen, F.; Oriekhova, A.; Brychko, A.; Shalyhina, I. Mapping the Literature on Sustainability Reporting: A Bibliometric Analysis Grounded in Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Kargina, M. A User-Friendly Method to Merge Scopus and Web of Science Data during Bibliometric Analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 10, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.C. An Evidence-Based Review of Academic Web Search Engines, 2014–2016: Implications for Librarians’ Practice and Research Agenda. Inf. Technol. Libr. 2017, 36, 7–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Wohlin, C. Systematic Literature Studies: Database Searches vs. Backward Snowballing. In Proceedings of the ACM-IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Lund, Sweden, 19–20 September 2012; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A Comparison Study of Specificity and Sensitivity in Three Search Tools for Qualitative Systematic Reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Booth, A.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Britten, N.; Garside, R. Defining the Process to Literature Searching in Systematic Reviews: A Literature Review of Guidance and Supporting Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Egan, M.; Lorenc, T.; Bond, L.; Popham, F.; Fenton, C.; Benzeval, M. Considering Methodological Options for Reviews of Theory: Illustrated by a Review of Theories Linking Income and Health. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Wang, L. Boolean Logic Function Realized by Phase-Change Blade Type Random Access Memory. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The Impact of Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) as a Search Strategy Tool on Literature Search Quality: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2018, 106, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, P.D.; Campiteli, M.G.; Kinouchi, O. Is It Possible to Compare Researchers with Different Scientific Interests? Scientometrics 2006, 68, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. The History and Meaning of the Journal Impact Factor. JAMA 2006, 295, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egghe, L.; Rousseau, R. An Informetric Model for the Hirsch-Index. Scientometrics 2006, 69, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, G. Exploring the H-Index at the Author and Journal Levels Using Bibliometric Data of Productive Consumer Scholars and Business-Related Journals Respectively. Scientometrics 2006, 69, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis-Oliveira, R.J. The H-Index in Life and Health Sciences: Advantages, Drawbacks and Challenging Opportunities. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. Former. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2019, 11, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.; Solé, I. Synthesising Information from Various Texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 24, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Agarwal, S.; Jones, D.; Young, B.; Sutton, A. Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence: A Review of Possible Methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, T.; Woods, M.; Atkins, D.P.; Macklin, R. The Discourse of QDAS: Reporting Practices of ATLAS. Ti and NVivo Users with Implications for Best Practices. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, A.H.; Alabri, S.S. Using Nvivo For Data Analysis In Qualitative Research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Educ. 2013, 2, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group*, P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Rana, S.; Goel, A. Presence of Digital Sources in International Marketing: A Review of Literature Using Leximancer. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2022, 16, 246–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; Iannone, B.V., III; Pijanowski, B.C.; Kong, N.; Fei, S. Automated Content Analysis: Addressing the Big Literature Challenge in Ecology and Evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Bloch, C.; Kranz, J. A Framework for Rigorously Identifying Research Gaps in Qualitative Literature Reviews; CoRe Publications: Camarillo, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, K.A.; Saldanha, I.J.; Mckoy, N.A. Development of a Framework to Identify Research Gaps from Systematic Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, D.A. A Taxonomy of Research Gaps: Identifying and Defining the Seven Research Gaps. In Doctoral Student Workshop: Finding Research Gaps-Research Methods and Strategies; Researchgate: Dallas, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Shuai, D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, D. Progress and Challenges in Photocatalytic Disinfection of Waterborne Viruses: A Review to Fill Current Knowledge Gaps. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 355, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaha, K.K. An Interpretive Phenomenological Study of America’s Emerging Workforce: Exploring Generation Z’s Leadership Preferences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner, K.E.; Morrow, R. Grounded Theory, Feminist Theory, Critical Theory: Toward Theoretical Triangulation. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2003, 26, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmond, V.A. The Point of Triangulation. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2001, 33, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, N.S.; Gomez, A.; Carlson, S.; Russell, D. Bridging the Research-implementation Gap Requires Engagement from Practitioners. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendrick, J.H. Multi-Method Research: An Introduction to Its Application in Population Geography. Prof. Geogr. 1999, 51, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guion, L.A. Triangulation: Establishing the Validity of Qualitative Studies. Edis 1969, 2002, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennex, M.E. Literature Reviews and the Review Process: An Editor-in-Chief’s Perspective. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Mengersen, K.; Bennett, S.; Mazerolle, L. Viewing Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis in Social Research through Different Lenses. Springerplus 2014, 3, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).