Institutions and Firms’ Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Avenues

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Procedures

3.2.1. Citation and Co-Citation Analysis

3.2.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

3.2.3. Thematic Map

4. Results

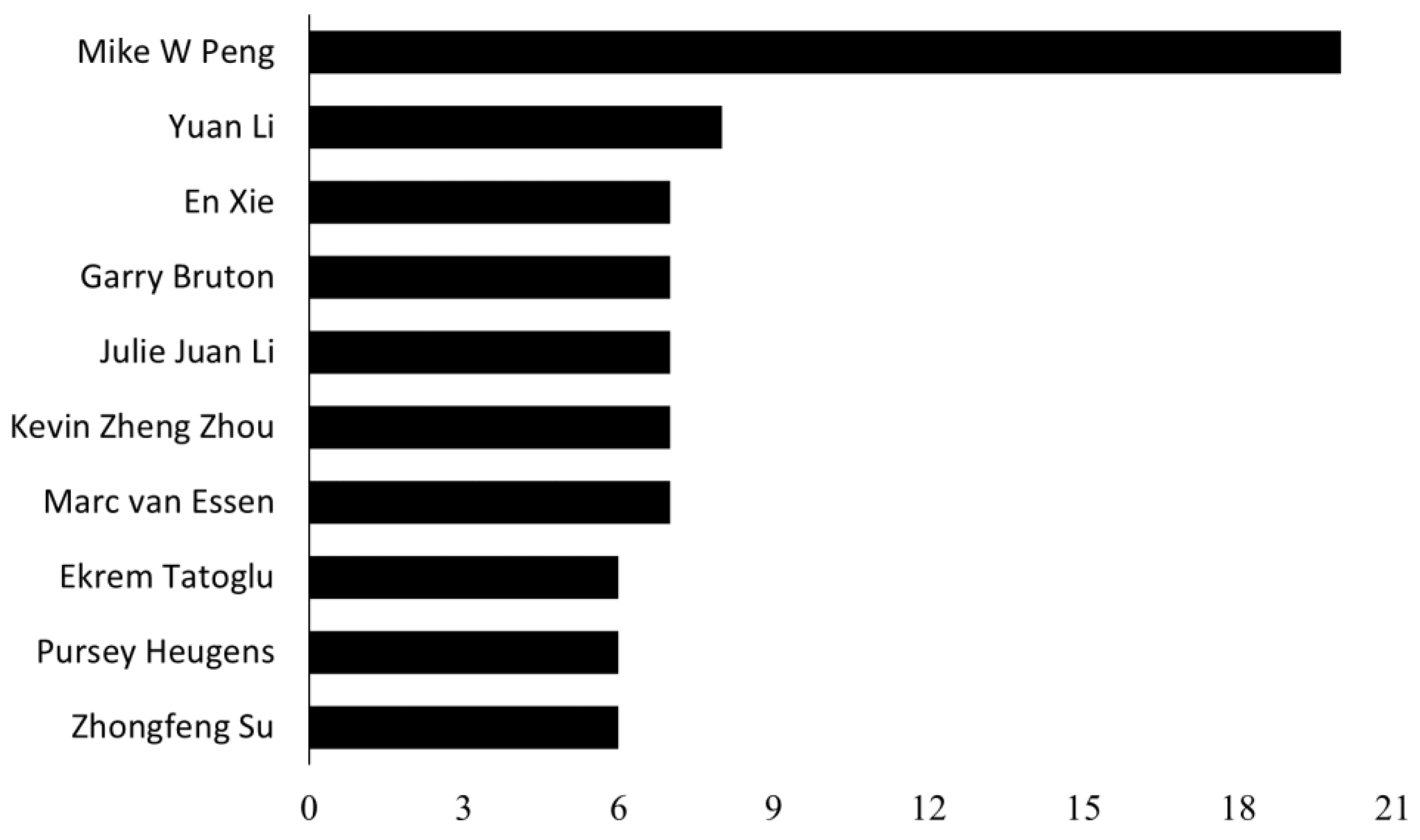

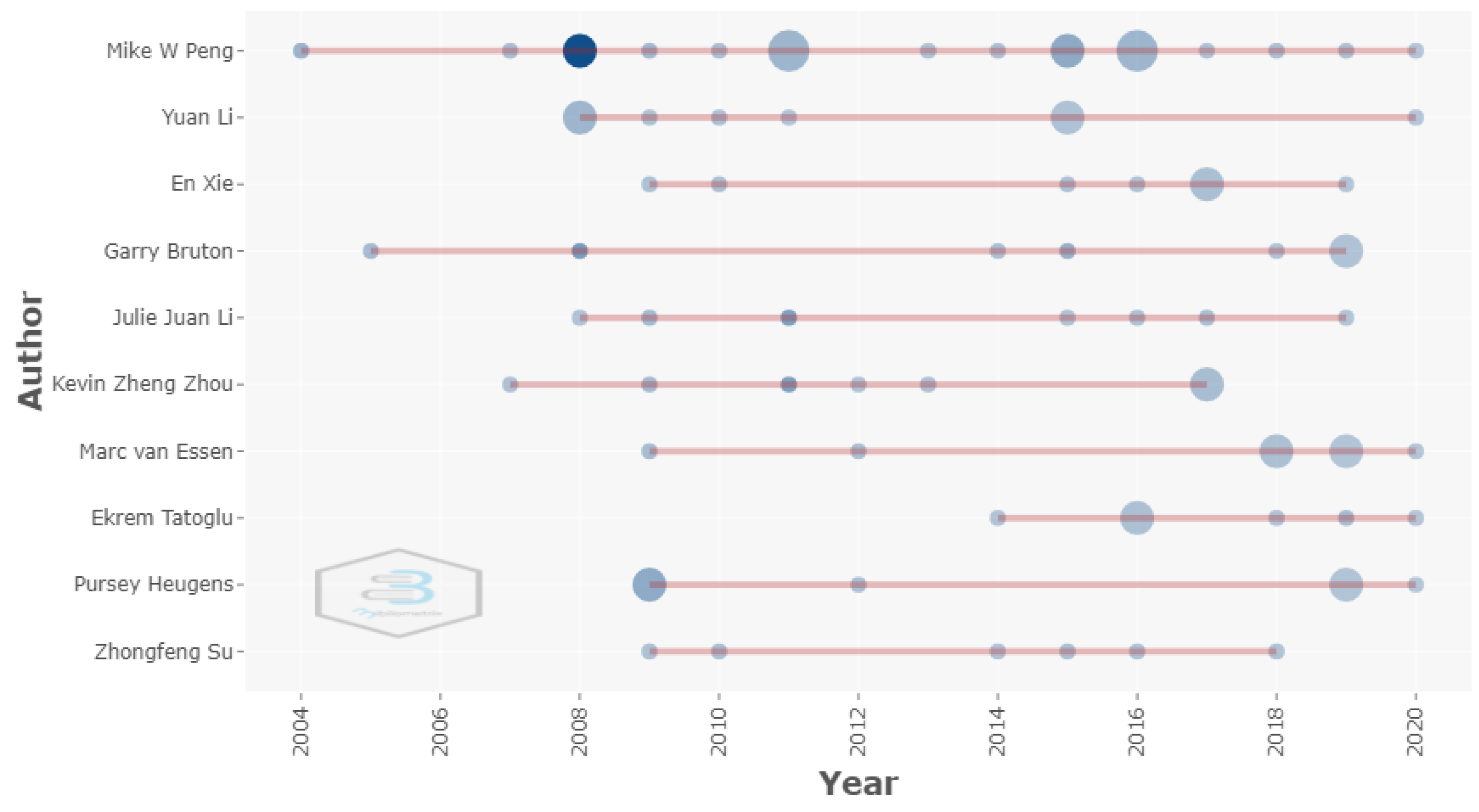

4.1. Citation and Co-Citation Analysis

| Work | Topic | LCS | GCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| [20] North (1990). | Institutions. | 290 | 60.000 |

| [19] DiMaggio & Powell (1983). | Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality. | 283 | 51.059 |

| [33] Barney (1991). | Resource-based view. | 173 | 77.364 |

| [17] Meyer & Rowan (1977). | Institutional environment and organizational structure. | 166 | 34.733 |

| [16] Scott (1995). | Institutions. | 148 | 8.457 |

| [36] Hoskisson et al. (2000). | Strategy in emerging economies. | 138 | 4.467 |

| [35] Oliver (1991). | Strategic responses and institutional pressures. | 128 | 10.854 |

| [37] Peng (2003). | Institutional transition and strategic choices. | 122 | 3.306 |

| [18] Suchman (1995). | Legitimacy. | 112 | 17.530 |

| [34] Khanna & Palepu (1997). | Institutional voids, emerging economies, and strategic decisions. | 103 | 3.156 |

| [38] Jensen & Meckling (1976). | Agency theory and ownership structure. | 102 | 95.825 |

| [39] Wright et al. (2005). | Emerging economies and strategic decisions. | 93 | 2.180 |

| [40] Peng et al. (2008). | Emerging economies and strategic tripod. | 92 | 3.049 |

| [41] Fornell & Larcker (1981). | Structural equation models. | 90 | 71.552 |

| [42] Pfeffer & Salancik (1978). | Social environment and resource dependence. | 83 | 35.206 |

| [43] Podsakoff et al. (2003). | Common method bias in behavioral research. | 80 | 47.544 |

| [44] Peng & Luo (2000). | Transition economies and firm performance. | 76 | 3.055 |

| [45] Campbell (2007). | Corporate social responsibility. | 75 | 4.569 |

| [46] Xin & Pearce (1996). | Guanxi as institutional support. | 65 | 2.771 |

| [47] Waddock & Graves (1997). | Corporate social performance. | 65 | 7.821 |

| [48] Orlitzky et al. (2003). | Corporate social and financial performance. | 65 | 8.398 |

| [49] Aiken et al. (1991). | Multiple regression analysis. | 64 | 47.345 |

| [50] Meyer et al. (2009). | Entry strategies in emerging economies. | 60 | 1.871 |

| [51] Oliver (1997). | Institutions, resources, and competitive advantages. | 60 | 4.020 |

| [52] Kostova & Roth (2002). | Institutional duality and multinational corporations’ subsidiaries. | 56 | 3.008 |

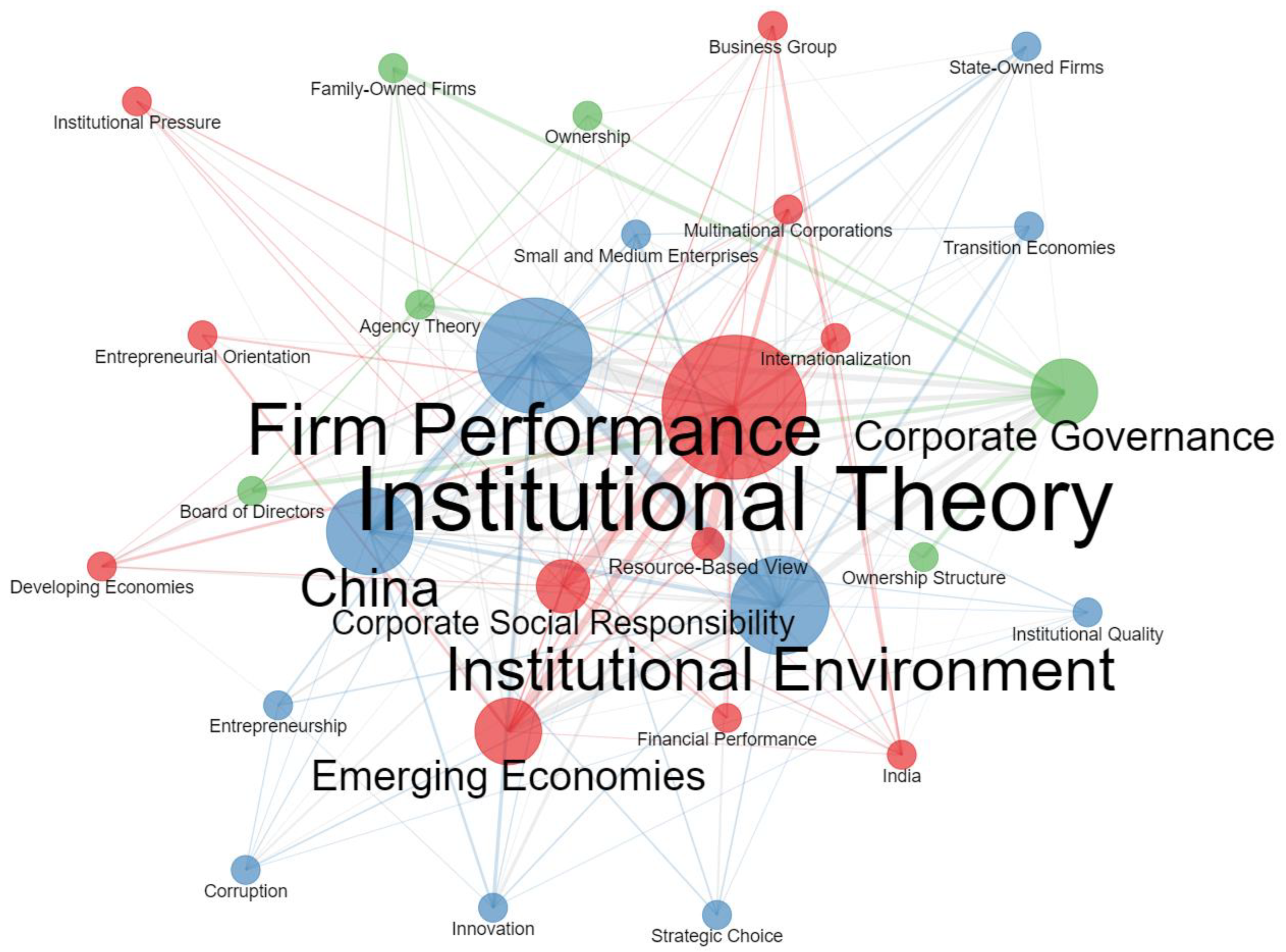

4.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

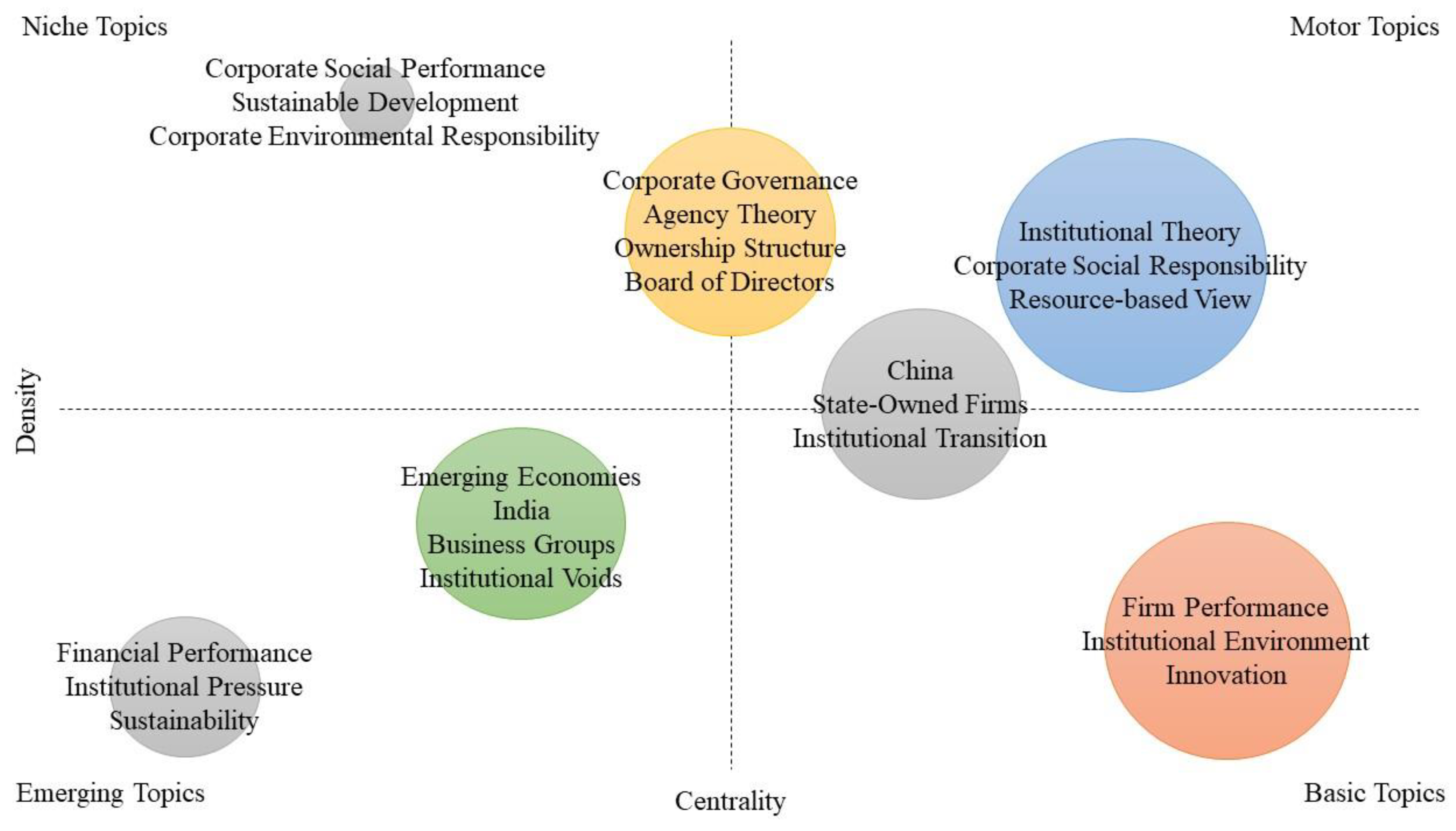

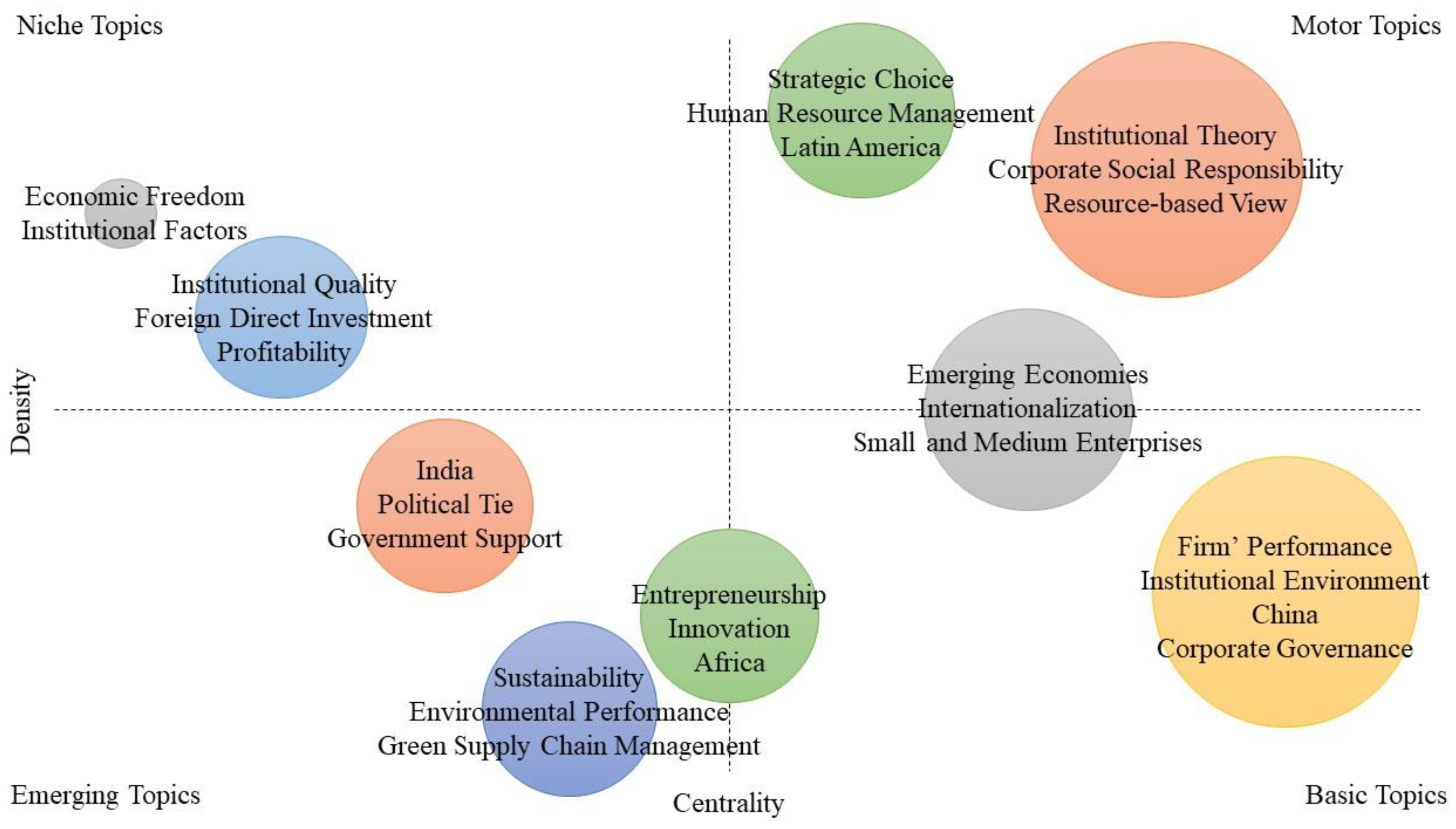

4.3. Thematic Map

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

5.1. Future Research Avenues

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liedong, T.A.; Peprah, A.A.; Amartey, A.O.; Rajwani, T. Institutional voids and firms’ resource commitment in emerging markets: A review and future research agenda. J. Int. Manag. 2020, 26, 100756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Beugelsdijk, S.; Scott, W.R.; Kunst, V.E.; Chua, C.H.; van Essen, M. The construct of institutional distance through the lens of different institutional perspectives: Review, analysis, and recommendations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Grøgaard, B. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Mudambi, R.; Pedersen, T. Clarifying the relationships between institutions and global strategy. Glob. Strategy J. 2019, 9, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafouros, M.; Aliyev, M. Institutional development and firm profitability in transition economies. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hitt, M.A.; Li, D.; Xu, K. International strategy: From local to global and beyond. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Hitt, M.A.; Brock, D.; Pisano, V.; Huang, L.S. Country institutional environments and international strategy: A review and analysis of the research. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; Manolova, T.S. Foreign location decisions through an institutional lens: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.W.; Buckley, P.J. Host country risk and foreign ownership strategy: Meta-analysis and theory on the moderating role of home country institutions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Arregle, J.L.; Hitt, M.A.; Spadafora, E.; Van Essen, M. Home country institutions and the internationalization-performance relationship: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1075–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleilate, J.M.G.; Magnusson, P.; Parente, R.C.; Alvarado-Vargas, M.J. Home country institutional effects on the multinationality–performance relationship: A comparison between emerging and developed market multinationals. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 22, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Duran, P.; Gómez-Mejía, L.; Heugens, P.P.; Kostova, T.; van Essen, M. Impact of informal institutions on the prevalence, strategy, and performance of family firms: A meta-analysis. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchakoui, S. Why and how to merge Scopus and Web of Science during bibliometric analysis: The case of sales force literature from 1912 to 2019. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, S.C.; de Benedicto, G.C.; do Prado, J.W.; Robb, D.A.; de Almeida Bispo, O.N.; de Brito, M.J. Mapping the literature on credit unions: A bibliometric investigation grounded in Scopus and Web of Science. Scientometrics 2019, 120, 929–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerras-Martín, L.Á.; Ronda-Pupo, G.A.; Zúñiga-Vicente, J.Á.; Benito-Osorio, D. Half a century of research on corporate diversification: A new comprehensive framework. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.R.; Carvalho, F.M.P.O.; Ferreira, J.V. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A bibliometric review and future research avenues. Int. J. Bibliometr. Bus. Manag. 2019, 1, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Reis, N.R.; Pinto, C.F. Two decades of management research on emerging economies: A citation and co-citation review. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2020, 50, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W.; Ha, N.C. Palm oil and its environmental impacts: A big data analytics study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Santos, J.C.; de Almeida, M.I.R.; Reis, N.R. Mergers & acquisitions research: A bibliometric study of top strategy and international business journals, 1980–2010. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Hug, S.E. Visualizing the context of citations referencing papers published by Eugene Garfield: A new type of keyword co-occurrence analysis. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, H.N.; Lee, P.C. Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: A first look at journal papers in Technology Foresight. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forliano, C.; De Bernardi, P.; Yahiaoui, D. Entrepreneurial universities: A bibliometric analysis within the business and management domains. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 165, 120522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, V.P.; Alon, I. Franchising research on emerging markets: Bibliometric and content analyses. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Strotmann, A. Analysis and Visualization of Citation Networks. Synth. Lect. Inf. Concept Retrival Serv. 2015, 7, 1–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Eden, L.; Lau, C.M.; Wright, M. Strategy in emerging economies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Filatotchev, I.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Peng, M.W. Strategy research in emerging economies: Challenging the conventional wisdom. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Wang, D.Y.; Jiang, Y. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 920–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.K.; Pearce, J.L. Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, K.E.; Estrin, S.; Bhaumik, S.K.; Peng, M.W. Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kostova, T.; Roth, K. Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and relational effects. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kamada, T.; Kawai, S. An algorithm for drawing general undirected graphs. Inf. Process. Lett. 1989, 31, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y. The role of managers’ political networking and functional experience in new venture performance: Evidence from China’s transition economy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mutlu, C.C.; Van Essen, M.; Peng, M.W.; Saleh, S.F.; Duran, P. Corporate governance in China: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 943–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, I.; Tatoglu, E.; Wood, G.; Demirbag, M.; Zaim, S. Corporate governance and firm performance in emerging markets: Evidence from Turkey. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözübüyük, R.; Kock, C.J.; Ünal, M. Who appropriates centrality rents? The role of institutions in regulating social networks in the global Islamic finance industry. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 764–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinez-Garcia, I.; Basco, R.; Gomez-Anson, S.; Boubakri, N. Ownership concentration in the Gulf cooperation council. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020. (advance online publication). [Google Scholar]

- Surroca, J.A.; Aguilera, R.V.; Desender, K.; Tribo, J.A. Is managerial entrenchment always bad and corporate social responsibility always good? A cross-national examination of their combined influence on shareholder value. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 891–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Patel, C.; Budhwar, P.; Katou, A.A.; Arora, B.; Dao, M. Institutionalism and its effect on HRM in the ASEAN context: Challenges and opportunities for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popli, M.; Akbar, M.; Kumar, V.; Gaur, A. Performance Impact of Temporal Strategic Fit: Entrainment of Internationalization with Pro-Market Reforms. Glob. Strategy J. 2017, 7, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Akter, M.; Odunukan, K.; Haque, S.E. Examining economic and technology-related barriers of small-and medium-sized enterprises internationalisation: An emerging economy context. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budsaratragoon, P.; Jitmaneeroj, B. Measuring causal relations and identifying critical drivers for corporate sustainability: The quadruple bottom line approach. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2019, 23, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Orlitzky, M.; Louche, C. How nation-level background governance conditions shape the economic payoffs of corporate environmental performance. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2714–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, D.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, V.; Terziovski, M. CSR ‘sustainability’ practices and firm performance in an emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beule, F.; Klein, M.; Verwaal, E. Institutional quality and inclusive strategies at the base of the pyramid. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E.; Shamah, R. Determinants of women entrepreneurs’ firm performance in a hostile environment. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Kedir, A.M. Business registration and firm performance: Some lessons from India. J. Dev. Entrep. 2016, 21, 1650016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Kedir, A.M. Starting-up unregistered and firm performance in Turkey. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kafouros, M.; Yi, J.; Hong, J.; Ganotakis, P. The role of government affiliation in explaining firm innovativeness and profitability in emerging countries: Evidence from China. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, T.; Shou, Z. The double-edged sword effect of political ties on performance in emerging markets: The mediation of innovation capability and legitimacy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2021, 38, 1003–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y. Institutional transformation and changing networking patterns in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2016, 12, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, P.; Qiao, K. Wining and Dining Government Officials: What Drives Political Networking in Chinese Private Ventures? Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 1084–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.N.; Zhu, H. Corporate governance dynamics of political tie formation in emerging economies: Business group affiliation, family ownership, and institutional transition. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2021, 29, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wood, G.; Khan, Z. Top management team’s formal network and international expansion of Chinese firms: The moderating role of state ownership and political ties. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, J.Y.; Augustine, D. Political ties and firm performance: The effects of proself and prosocial engagement and institutional development. Glob. Strategy J. 2018, 8, 471–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Gaur, A.; Singh, D. Pro-market institutions and global strategy: The pendulum of pro-market reforms and reversals. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 598–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, M.D.; Banalieva, E.R. How do pro-market reforms impact firm profitability? The case of India under reform. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, L.A.; Purkayastha, S.; Eddleston, K.A. Who does it best? Family and nonfamily owners and leaders navigating institutional development in emerging markets. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T. Institutional quality and market selection in the transition to market economy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Duarte, C.; Vidal-Suárez, M.M.; González-Díaz, B.; Reis, N.R. Understanding the relevance of national culture in international business research: A quantitative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 1553–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.E. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.; Guillén, M.F.; Zhou, N. An institutional approach to cross-national distance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1460–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Most Relevant Countries | n | Most Relevant Sources | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 199 | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 50 |

| 2 | China | 149 | Strategic Management Journal | 41 |

| 3 | United Kingdom | 70 | Journal of Business Research | 35 |

| 4 | Spain | 41 | Journal of World Business | 30 |

| 5 | Australia | 30 | Journal of Business Ethics | 29 |

| 6 | Canada | 24 | Journal of International Business Studies | 28 |

| 7 | Germany | 24 | Business Strategy and the Environment | 23 |

| 8 | Korea | 21 | International Business Review | 21 |

| 9 | India | 19 | Management International Review | 20 |

| 10 | Hong Kong | 17 | Organization Science | 18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, A.; Carvalho, F.; Reis, N.R. Institutions and Firms’ Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Avenues. Publications 2022, 10, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10010008

Oliveira A, Carvalho F, Reis NR. Institutions and Firms’ Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Avenues. Publications. 2022; 10(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Alexandre, Fernando Carvalho, and Nuno Rosa Reis. 2022. "Institutions and Firms’ Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Avenues" Publications 10, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10010008

APA StyleOliveira, A., Carvalho, F., & Reis, N. R. (2022). Institutions and Firms’ Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Avenues. Publications, 10(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10010008