3.1. First-Approach Perceptions: Major Challenges of the Graphical Abstract as Hybrid Genre

Regardless of their semiotic mode, host genre and format, abstracts have been defined as screening devices and previews of the research article [

25], as selective representations rather than accurate summaries [

26], and as promotional devices [

26], even being metaphorised as the ‘shop windows of science’ [

27] (p. 2). Visual abstracts could be labelled as ‘hybrid’ (see Bhatia [

28,

29]) or ‘enculturated’ research genres due to their intersemiosis and interdiscursivity. They merge creation and mimesis, the verbal and the visual, naturalistic and symbolic representations, and borrow elements from a variety of discourses, such as marketing and advertising, fiction literature, the graphic novel and the comic book, cartooning, photography and film. They are also multifunctional because they simultaneously encapsulate, engage, promote and serve as complex metadiscourse items. In this last respect, they may act as goal announcers providing the ‘roadmap’ of the article, as code glosses by means of embedded metaphorical narratives and analogies, as cognitive directives guiding the addressees’ interpretation, as stage-labellers (if they consist in a single frozen image), and as attitudinal markers (depending on the type of rendition and artwork).

It is uncertain whether this enculturation or hybridity will result in acculturation, that is, in the total loss of idiosyncratic values and features due to the adoption of the dominant culture, in this case, that of marketing and advertising, or in a definitely failed democratisation of science dissemination. What seems clear is that, in visual abstracts, the deferential writer-responsible values of academic writing are giving way to a reader-responsible culture in which it is up to the readers/viewers to expose themselves to the stimulus or target information and focus their attention to finally recognise the message. This is the principle of the advertising–marketing culture [

30,

31,

32], in which overt metadiscursive engagement markers (e.g., rhetorical questions, reader pronouns and mentions, asides, directives and expressions of shared knowledge in Hyland’s 2005 taxonomy [

23]) are not resorted to as much as in academia. Perhaps this displacement of responsibilities and orientations (from writer-responsible or reader-oriented to reader-responsible or writer-oriented) is the most remarkable discursive practice introduced by visual abstracts, which entail a threefold challenge (

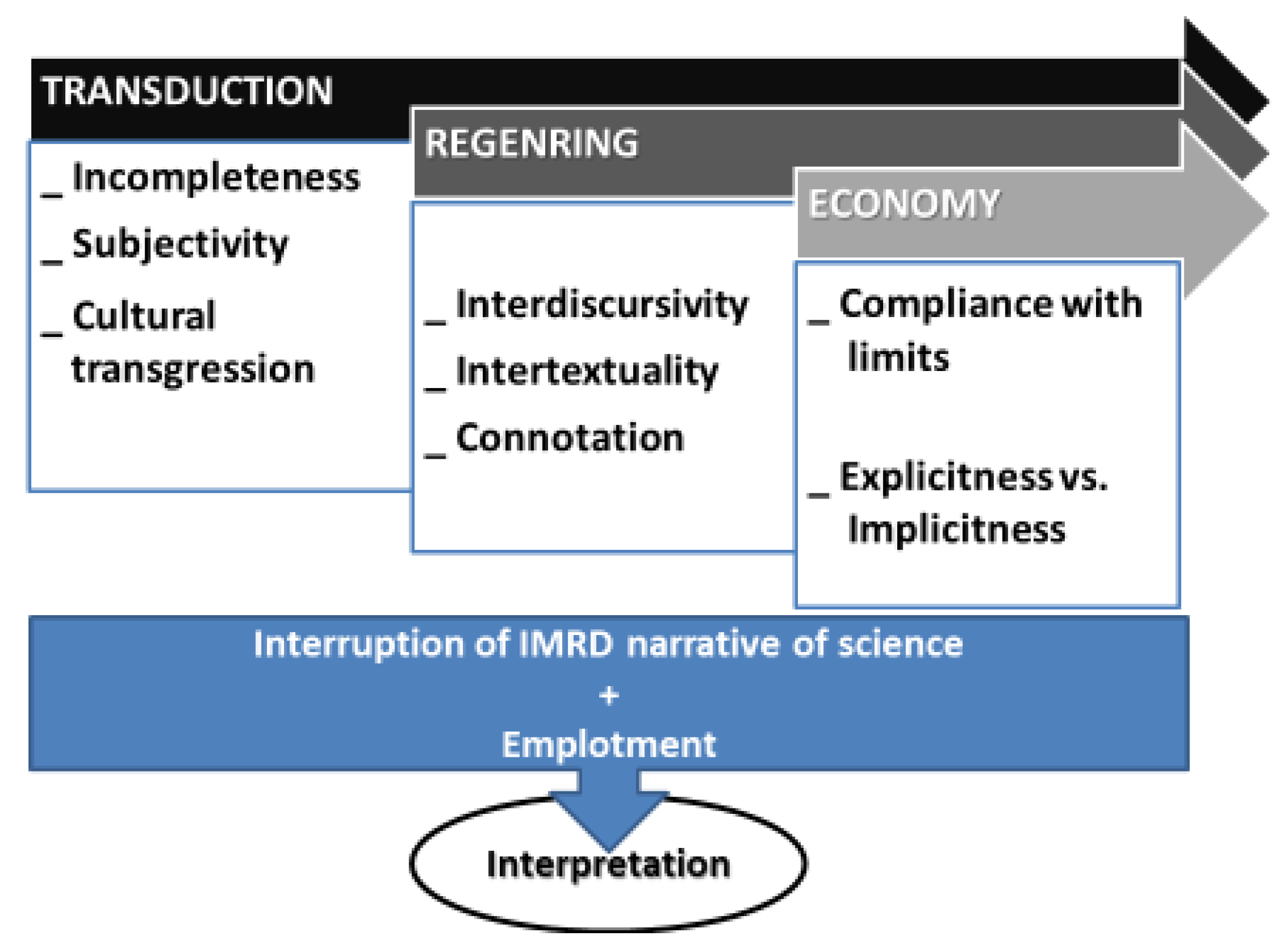

Figure 1):

transduction [

33], termed ‘semiotic remediation’ by Prior [

16],

regenring [

34], called ‘re-purposing’ by Prior [

16], and

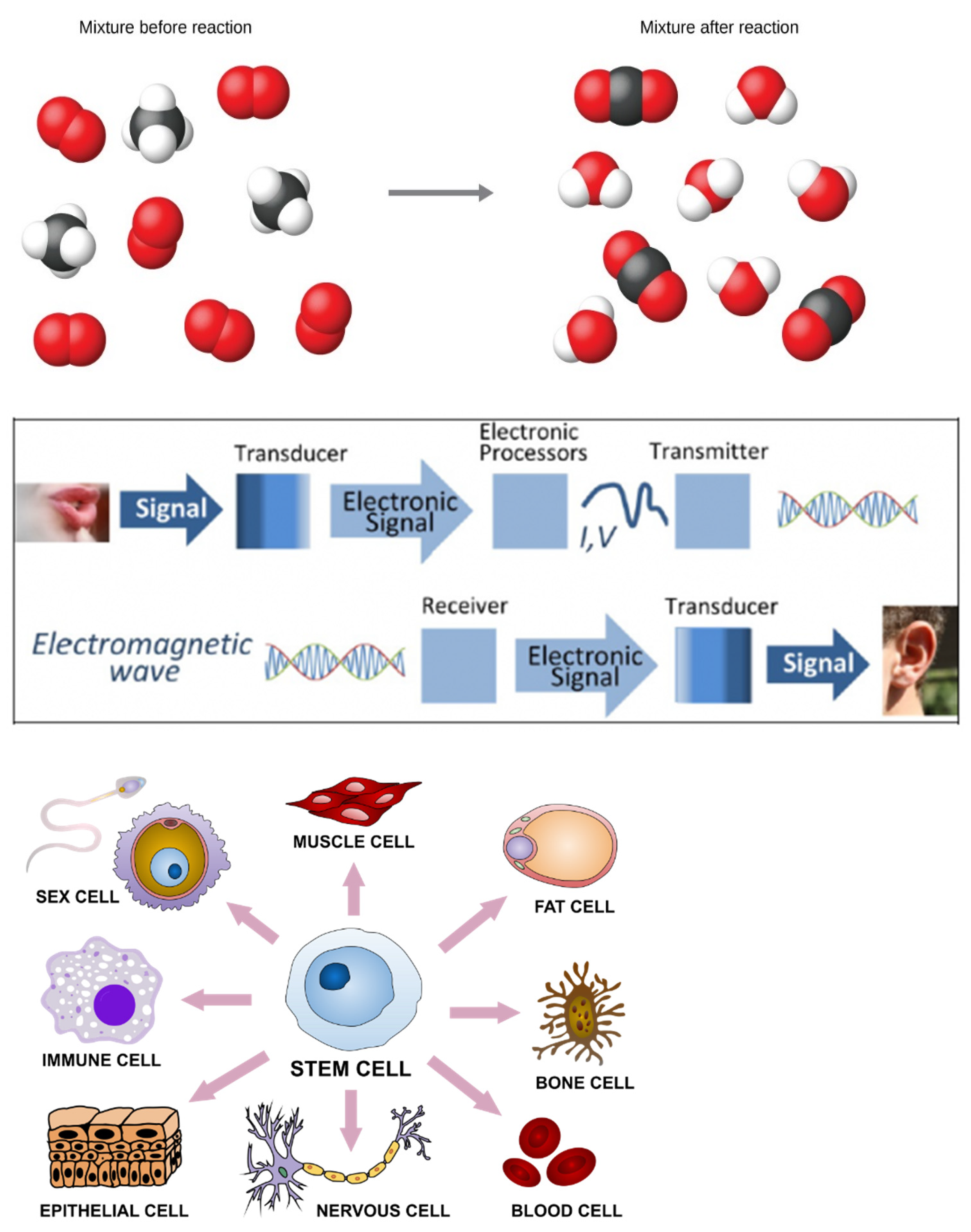

discourse economy.Transduction is the resemiotisation of content into a different mode of meaning: in the case of GAs, the conventional verbal summary of scientific articles, on average ranging from 100 to 300 words, is converted into an image or series of images fitting into a single panel. Regenring is a genre shift that modifies (either by clipping, by elaboration, or by some other type of manipulation) and reorganises that content in a way and with a purpose that substantially differ from the original aim, arrangement and/or extension. Discourse economy imposes extension limits, be they as a maximum footage duration for video abstracts, restricted space (frequently one panel) for GAs, number of points or aspects dealt with (so as not to clutter the space available for GAs and prevent cognitive overload in video abstract viewers), file size, colour palette and saturation, and inclusion or exclusion of verbal text. All these limits and restrictions depend very much on journal policy.

The challenges inherent in transduction are incompleteness, subjectivity and cultural transgression. Static visuals are holistic and cannot express verbal content fully, so the information conveyed in a GA must necessarily be incomplete. Incompleteness normally impinges upon the representation of stages in the research process, as GAs showing a complete IMRD narrative sequence (i.e., Introduction–Method–Results–Discussion/Conclusion) do not abound. The addressee must then work out what moves are shown, which tend to be the methods and results stages in a sort of ‘before’ and ‘after’ narrative sequence. Yet the perception of qualitative evolution or of changes of state or condition is not always immediate because it may depend on minimal visual detail that requires full attention and not be guided by vectors (arrows or lines indicating the reading path) but by contiguous collocation. In such cases, as in sample (1), the cognitive processing effort is high and resembles the pastime activity of ‘spot the differences’ between two diagrams depicting two consecutive phases in the process of cellular resistance to anticancer agent doxorubicin. For the non-expert viewer or for experts with an untrained eye, such cognitive investment goes against the immediacy and efficacy expected from good summaries.

- (1)

- (2)

It may happen that the vectorless stage sequence consists of two disparate representations, as in sample (2), which contrasts a drawing sketch and a photograph of the same object of study (a beam joint) during a testing procedure. The legends explaining each image are not very telling, and neither are the ‘frozen moments’ captured in the visuals. These two samples are prototypical instances of compositional stylisation or layout subjectivity, which shall be further explored in a following section.

The selection of genre moves and steps, topical aspects and composition layouts is subjective and may go against the representational tradition of a given culture or even incur social taboo. A good case in point is Sample (3), which represents the properties of certain chemical elements as human behaviour. The resonance effects and affinity or bonding potential between zinc and selenium are metaphorised as a two-panel disco dance scene involving human silhouettes, where a female character in a mini-skirt (marked as zinc) dances provocatively to attract a male figure embodying selenium. This type of rendition may be not only misunderstood by certain cultures but also come across as offensive to particular religious creeds and gender collectivities with different mindsets and derived social roles, since the female character in (3) might appear as much too disinhibited or even lewd for some.

- (3)

In a similar vein, regenring may—intentionally or not—involve discoursal and textual loans and connote other interactions from distant spheres of human activity (e.g., journalism, art, fiction, advertising, comics, movies, etc.), but their perception is obviously conditioned by the addressee’s cultural background and interpretive skills, particularly by metaphorical thought. Sample (4) is an instance of interdiscursivity with a discourse borrowed from outside science, concretely from Marketing and Advertising. The image in question verges on regenring because of its resemblance with a billboard or press advertisement, especially in its close-up take of the object/product to be promoted or paid attention to, and the involvement of the audience through a rhetorical question without any contextualisation and a direct appeal through the second person pronoun (‘you’). In addition, the proximal tone achieved is characteristic with an ‘exclusive we’ pronoun as a marker of both nearness and authority.

- (4)

More conspicuously perceived than interdiscursivity, intertextuality aims at establishing ‘universal analogies’ by using visual and/or verbal references to widespread texts from literature, film, videogames, sports and other fields of human activity, as well as cultural icons and symbols and other presumably widespread life experiences. The choice of ‘universal’ references is per se subjective, despite the global reach of digital networks and other mass media: Can it be ensured that, say, an Asian or African scientist is fully familiarised with well-known works of art and literary and filmic canons from the western culture? And why should the western culture be the only referential basis for every connotation, analogy, metaphor and comparison used to disseminate and promote scientific achievements? Is it due to a population size criterion or to a matter of power?

It cannot be denied that, by and large, science and technology are practically in the hands of a few highly industrialised countries with a Judeo–Christian origin, but that should not oblige experts with other backgrounds to acquire the cultural level necessary to decode scientific content in a genre whose major purpose is screening and encapsulating, not entertaining. However, messages praising the aesthetic and amusing qualities of visual abstracts, such as that launched in 2018 by biologist and journalist Kerry Evans (Senior Managing Editor for AJHG and Immunity and in charge of the Cell Press blog ‘Crosstalk’), have fuelled the idea that entertaining is part of their objective. She holds that there is no reason why Cell’s video abstracts cannot be enjoyed by lay readers/viewers:

“Just because Cell video abstracts are primarily intended for scientists doesn’t mean your kindergartener or grandparent can’t enjoy this.”

To the discourse analyst, nonetheless, entertainment without content comprehension is difficult to imagine, and chances that scholars gloss their scientific texts for laypeople are really thin unless the intention is to produce an outreach version. The publishers’ view of scientific communication between experts as an amusing interaction seems then to clash with that of scholars, for whom it is a concise, informative transaction with a high degree of taken-for-granted knowledge.

While the verbal abstract is infallibly literal, monosemic and discourse-specific, its graphical and video variants are allowed to be metaphorical and interdiscursive, even polysemic for the ideal audience, depending on the degree of literalness adopted. This fact might lead us to think that the intended addressees of verbal and graphical abstracts could be different, although no scholar has as yet disclosed an intention to reach out to laypeople by means of GAs. Sample (5) expresses scientific doubt with the Shakespearian plot of

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. As shown in (5), the ‘ad hoc pointer’ [

36] or ‘metaphorical trigger’ that signals the metaphorical nature of the encoding is the molecule held by the character dressed in a 16th-century attire, who should instead hold a skull, according to the Shakespearian play. The verbal and phonic pun of the title “tBu or not tBu?” (a question which emulates Hamlet’s famous soliloquy “To be or not to be, that is the question”) is another pointer, tBu being the name of the ligand molecule studied. In the verbal paraphrase of the GA facilitated by the journal (very few publishers do), the authors describe their article as ‘a Hamlet study’, a qualification that contrasts starkly with the technical register used in the remainder of the paraphrasing paragraph.

- (5)

Intertextual choices likely to be less ‘universal’ are (6), an allusion to the sentence “Quo vadis?” from the Acts of Peter, one of the earliest apocryphal Acts of the Apostles in Christianity and later on inspiration for Henrik Sienkiewicz’s 1896 novel Quo Vadis , and the national folklore instances showcased by (7) and (8), which respectively embody Aesop’s fable The Hare and the Tortoise and the popular idiom ‘carrot-and-stick’, used to denote a dual motivational approach consisting in reward and punishment. In both samples, the authors have spared any verbal clue, which indicates that they regard their cultural referents as accessible enough.

- (6)

- (7)

A yet more subtle level of decodification based on evoked concepts or situations/scenes is connotation. Sample (8) parodies the TV programme The Joy of Painting, broadcast between 1983 and 1994 in the USA by PBS. In it, artist Bob Ross (1942–1995), soon a celebrity, painted canvases live in less than 30 min to explain diverse rapid pictorial techniques. The palette held by his caricature in this GA contains only cobalt blue dollops, and his paintbrush represents the zinc element, with which the brushstrokes on the canvas seem to be applied with extreme smoothness. The artist’s characteristic permed hairstyle is here hexagonally shaped, iconic of the catalyst molecule under research. The processing of the information conveyed in this GA is not easy for scientists unexposed to the said TV programme, whose metaphorical scenario is not directly related with the research topic, but laterally suggested by the shared features of rapidity and simplicity: the cobalt–zinc catalyst is as quick and smooth as Ross’ painting. How many researchers from outside the USA are able to recognise the caricature and then deduce this implicit association? Undoubtedly, Bob Ross has had an impact beyond the U.S. frontiers because, curiously enough, the GA authors are four German scholars based in Munich and a Chinese national affiliated to Wuhan University, but surely Ross’ popularity will vary across countries and his figure may be unknown in some of them around the globe. It remains uncertain how the five authors became acquainted with the celebrity and whether they took for granted a ‘universal’ audience for their GA. Can this case be considered an instance of cultural colonisation or imposition within the scientific community?

- (8)

To conclude, the compliance with extension limits and the primary goal of summarising content brings along a discursive economy in the form of omission (of information taken for granted or considered superfluous) or implicitness (information subtly hinted at in a visual manner). Variations on the hare-and-tortoise motif containing only one of the two characters in the story, most often the victorious turtle (see Sample 9), exemplify the strategy of omission and assume that addressees know the plot, which makes it unnecessary to include the defeated hare. Sample (10) is another mixture of omission and implicitness: the addressee’s knowledge of the chemical arrangement of the nanoparticles under study theoretically suffices for a successful interpretation of the image, although it may not be so in practice.

- (9)

- (10)

So far we have seen how the three main challenges generated by visuality in science dissemination (i.e., transduction, regenring and discursive economy) frequently cause the interruption of the IMRD narrative sequence of GAs or intervene in it and lend themselves to embedded emplotments devised to epitomise, clarify through metaphorical analogies and seek memorability of the scientific content, all of which affect interpretation. We have also had the opportunity to observe that in many instances there is a stylised or subjective presentation of the visual message. Let us now turn to the definition of the stylisation phenomenon and its repercussions upon science dissemination.

3.2. Finer-Grained Results: A Working Definition of Stylisation, Taxonomy and Outstanding Issues

Stylisation is not all about embellishment, although part of it may be aesthetically motivated. I define the concept as a subjective encoding of information, in this case scientific, out of pragmatic and aesthetic reasons, which frequently leaves an authorial imprint and affects the comprehension of the message. Stylisation has to do with individuals’ creativity and subjectivity, since it does not strictly follow external guidelines and norms, may traverse all the three major challenges posed by visuality (i.e., transduction, regenring and discourse economy—see again

Figure 1), and even operate metaphorically by recounting scientific and technical facts with embedded non-scientific narratives. In these, recourse to intertextuality, interdiscursivity metaphorical scenarios and connotation (the latter in more subtle encodings) is common. Some instances have already been shown in samples (3)–(10).

Hence, stylisation may deal with notional, interactional and compositional aspects alike (i.e., roughly corresponding with the functions of language put forth by Systemic Functional Linguistics: ideational, interactional and textual) and exhibit varying degrees of complexity that range from mere ornamentation to multiple metaphorical embodiments, sometimes nested.

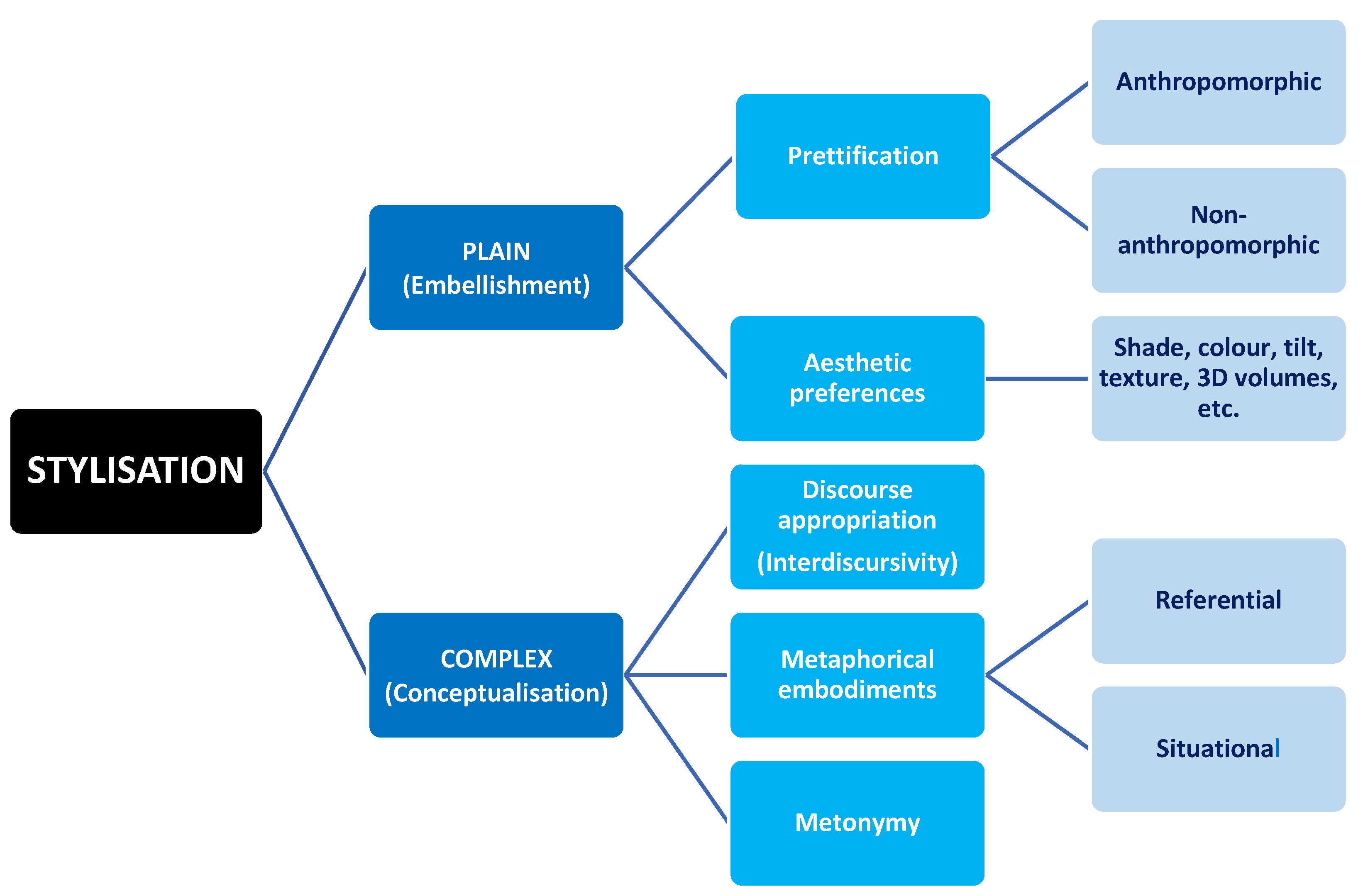

Figure 2 shows a taxonomy proposal that divides stylisation into ‘simple’ (essentially consisting in embellishment) and ‘complex’ (conceptualising facts or phenomena).

Within plain stylisation (i.e., embellishment), ‘prettification’ is the term used by science bloggers to denote the subjective representation of chemical elements and compounds, atoms and molecules, microorganisms, animals, plants and processes as animate beings, among which anthropomorphic shapes and facial expressions are rife. Samples (11) and (12) are instances of anthropomorphical prettification. While the one in (11) does not seem to affect the interpretation of the scientific information, that of (12) might contribute to a more accurate comprehension since the prettified molecule has additionally been metaphorised into a human archer aiming his/her arrow at a chemical (O2) target, which suggests agency and accuracy on the part of the substance prettified. A case of non-anthropomorphic prettification is (13), where the sweetener molecule synthesised is metonymically rendered as ice cream on a wafer cone.

- (11)

- (12)

- (13)

It is not common to find visual metonymy in isolation. Very occasionally, it is used to represent actions that integrate the methods stage in the research and epitomises those actions with the instruments or tools with which they are performed: for example, a syringe for inoculation, a stove for drying, a tap for water rinsing, or a clock for waiting time. Metonymic ‘purity’, anyhow, is a debatable concept, as all the former instances could be conceived as metaphors under the conceptual schema an action is its instrument/tool.

Prettification, oftentimes aided by cartooning and comic book techniques, brings about register shifts that trivialise the communication or turn it into an informal interaction. In (14), two molecules have human-like bodies and, although faceless, speak and their utterances appear contained in speech bubbles, whereas in (15), a thought balloon is attributed to an insect. Certainly, these kinds of stylisations do not hamper the democratisation of science: they do not segregate readers/viewers nor hinder the grasp of scientific content but contribute to ingraining the goal of entertainment in science dissemination, which might end up threatening interpretation if pursued at all costs.

- (14)

- (15)

Aesthetic preferences involving colour, shading, image orientation, texture, or three-dimensional effects are potentially less innocuous than prettification, as Sample (16) demonstrates. The arbitrary shading of its molecule segments may lead to a mistaken interpretation of the shaded areas as bonding surfaces, an ambiguity criticised by science bloggers.

- (16)

All in all, then, the chief dangers of stylisation, be it strictly graphical or conceptual, are trivialisation, exclusion and misinterpretation—the latter two repercussions even among experts. Displayed in

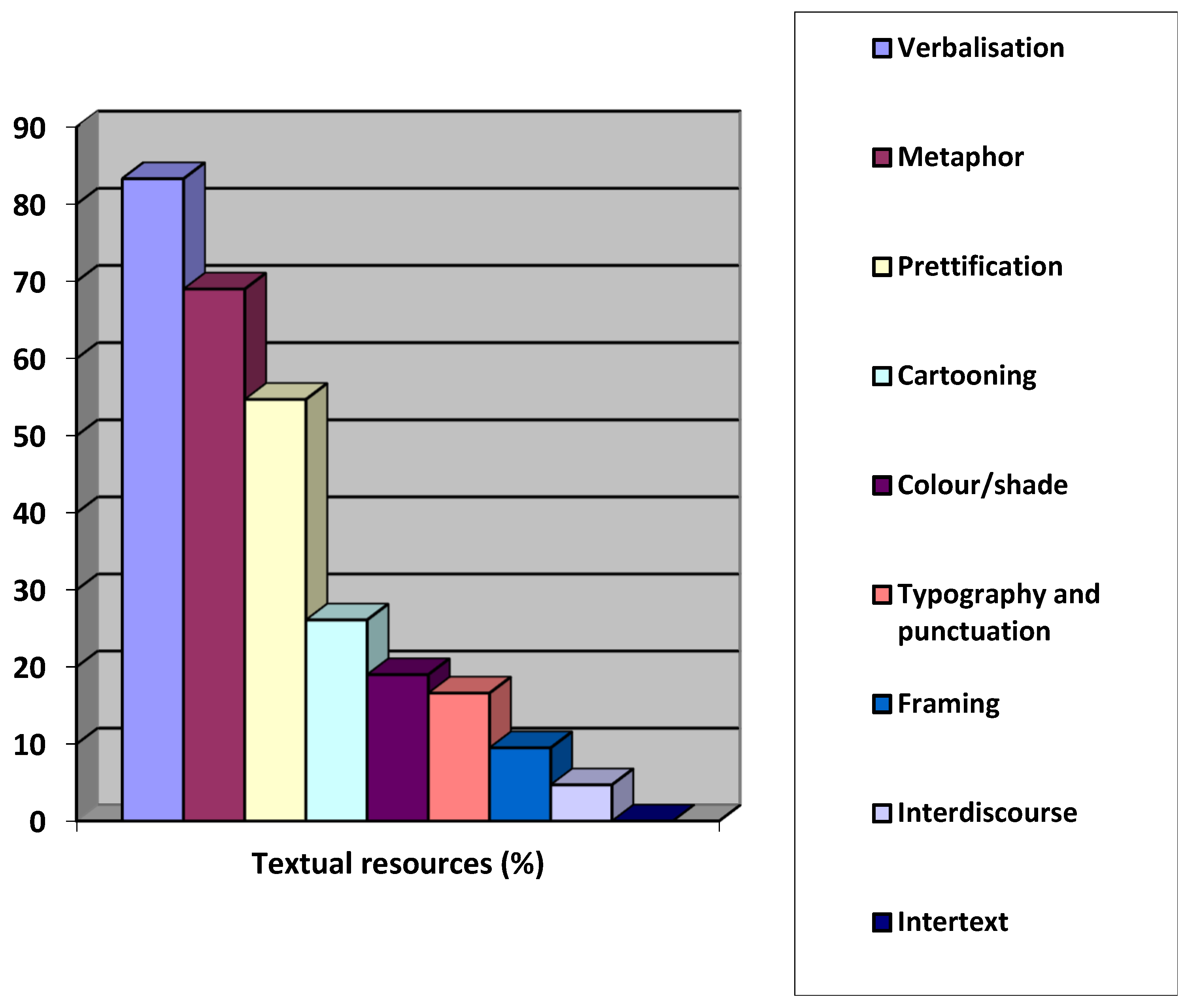

Figure 3 are the resources causing the GAs selected from the TOC-ROLF science blog to be deemed ineffective in their summarising, screening and disseminating function.

Noticeably, there is a predominant use of verbal insertions (83.3%), mostly of succinct noun phrase labels (73.8%). By contrast, verbalisations comprising one or more sentences are relatively scarce (9.5%) and associated with speech bubbles and thought balloons, two cartooning techniques that inevitably shift the academic register into an informal interaction. Other techniques present are creative panelling, spiky balloons to denote loud sound, clash or violent reaction, explanatory captions and movement runes. Slightly over half of the samples (54.7%) prettify human characters, animals, objects, molecules and chemical elements or substances, and somewhat less than 20% make use of shading and colour saturation, which also alters the register. Only two instances appropriate the visual discourse of Advertising: one with a close-up photograph of a glass of beer with the printed question “How many bubbles?” as the hook, which clips the engaging title of the article “How many CO2 bubbles in a glass of beer?” (17):

and the other (18) with a full-blown mimic of a cow that intriguingly resembles that of the ‘La vache qui rit’ brand icon

2, of the Groupe Bel food firm:

Finally, also worthy of attention are the facts that recourse to intertextuality is non-existent and that metaphor is the second most used device (a little below 70%), but with a prevalence of object- or concept-based mappings (45.2%) over scenario-based ones (23.8%) in the source domain. None of the science metaphors detected evokes works of art, literature or film but prosaic life experiences applied to the target entities or processes to be described, or extremely unrealistic situations created ad hoc. Some examples of each variant are presented in

Table 1, which rates their proximity or familiarity to the addressee (‘commonplace’ versus ‘unrealistic’ objects and experiences). Regardless of these two degrees of proximity, however, there is always a ‘metaphorical trigger’ or ‘ad hoc pointer’ [

36], an incongruous element that beacons the need for not interpreting the embodiment literally. Prettification itself, some bizarre visual associations (e.g., a string coming out of a molecule for a cat to play with, perhaps representing bonding lengths), the insertion of scientific matter (e.g., chemical formulas and mathematical calculations, molecular models and microscopic images), verbal labels, or even colour saturation and whimsical framings are but a few of the devices serving as triggers.

In the context of science and technology dissemination, necessarily monosemic, economic and linear in the rhetorical organisation of its specialised discourse, many interpretive difficulties at a structural level reside in the motivation of the metaphorical embodiments of abridged visual texts, such as GAs and video-abstracts. It is relatively easy, therefore, to identify metaphorical triggers and the elements that are ‘out of place’, but sometimes it is rather complicated to find out the relationship between the source and target entities, no matter the amount of technical expertise. Occasionally, the covert motivation is subtly metonymic, as in the GA (mentioned in

Table 1) showing a prettified Santa Claus-like molecule of holmium oxyhydride at a sunny beach to suggest thermal stability. The relationship has to do with the stoichiometric composition (HoHO) of the substance, reminiscent of Santa’s typical laughter (19):

In another of the samples (20), also referred to in the table, an octopus-like chemical compound with a hat on to protect its ionic head, is sitting on a gold ingot, in front of several switches. The whole scene refers to the compound’s multiple ligand properties, equated with eight tentacles, particularly with gold and with a view to developing nanoscale molecular switching materials:

This small-scale analysis brings to light the complex metadiscursive multifunctionality of GAs: at a macrolevel and according to Hyland’s categorization [

23], they work as engagement markers (i.e., as attention-getters and cognitive directives guiding the addressees’ interpretation) and as glosses (via some vectors, didactic metaphors and embedded narratives parallel to or interrupting the rhetorical IMRD pattern of science dissemination). They also function as evidentials, if they consist of visuals displaying results from the original study and serve as goal announcers when inserted in the research article between the authors’ names and affiliations and the introduction. At a microlevel, they may contain a wide array of visual metadiscourse items in tension between mimesis and expression, a rooted feature of science iconography [

37]. Many such items coincide with the elements enumerated by Kress and van Leeuwen’s attempt [

21] at building a visual grammar and with Machin’s prompts for multimodal analysis [

22], both of which comprise vectors (arrows, lines, runes, etc.), frames, collocation, sizes, light and chromatic effects, typography, perspective and angles of interaction, and degrees in the articulation of detail. This coincidence of resources, most probably, will be the result of intuitive choices on the scholars’ end, who very seldom receive any institutional training in visual design.

In light of all the former, it is reasonable to expect that repertoires vary across disciplines and in the end position scholars and research areas with regard to the scientific message and its intended audience. A skimming look through the TOC-ROLF archive since its earliest entries in August 2010 reveals that some motifs are ‘endemic’ to certain scientific fields, such as the use of Aesop’s hare and tortoise fable to qualify the efficacy of catalysers and chemical reactions in Physical Chemistry and Chemical Physics. Storylines of this kind (provided by metaphorical scenarios from literature, film and folklore) constitute, together with speech acts (especially interrogative and commissive ones, in the form of rhetorical questions and verbal or visual commands) and past and imposed positions, the three pillars of any positioning action, which are known as ‘positioning cluster/triangle’ [

38]. By ‘past positions’ we should understand the scientists’ dissemination trajectory in publishing and public speaking, with all the visual resources they have employed thus far out of personal preference in GAs, in-article illustrations, and slides for lectures and conference presentations. By ‘imposed positions’ we should interpret the vetoes, restrictions and encouraged options (e.g., exemplars, templates, imitation trends in scholarly circles and author guidelines in general) fostered by the discipline or field and by scientific journals and conference committees.

Logically, the recording of individual positioning turns very difficult, because it implies tracking the ‘visual biography’ of each researcher diachronically along his/her academic career and across different genres, whereas the synchronic description of disciplinary and editorial positions, of collective ‘visual identities’, is more feasible. On the other hand, and as happens with verbal metadiscourse items in Hyland’s taxonomy [

23], certain visual resources may be overlappingly perceived as members of different categories. Arrow-shaped vectors, for instance, may be decoded as interactive and interactional at the same time; that is to say, as sequencers and cognitive directives (engaging commissive markers), whereas the expression of dissuasion, disapproval or rejection of actions not to be performed in a particular scientific procedure are more explicitly and unambiguously marked by sad or angry emoji gestures, red crosses and prohibition signs. Just like verbal metadiscourse, in sum, one item may fulfil several functions and one function may be performed by several forms, which in GAs jeopardises interpretation even more than in the verbal encodings of conventional abstracts, given that visuals are by nature holistic and schematic and GAs offer very little room for verbal inserts and proper contextualisations.

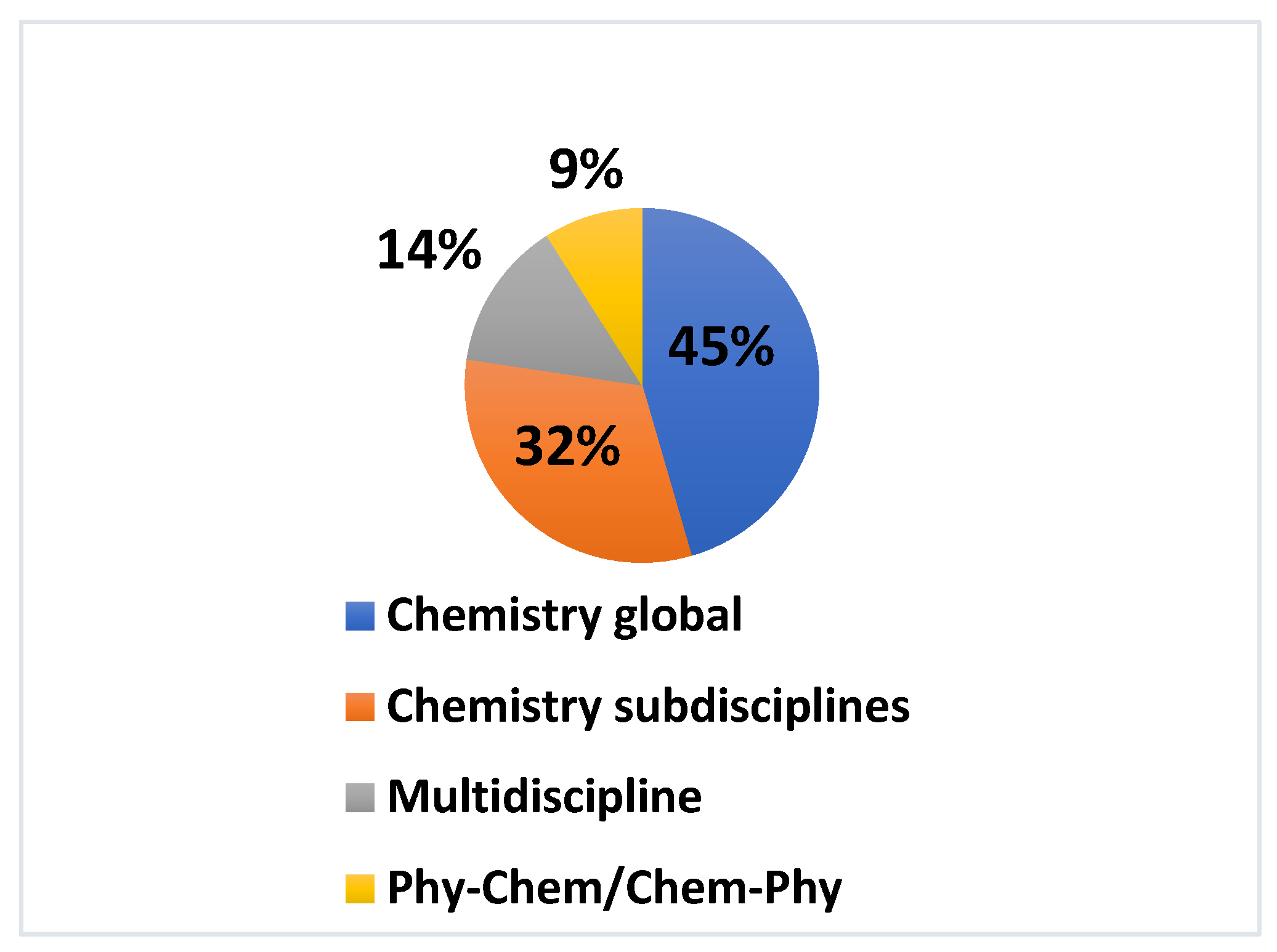

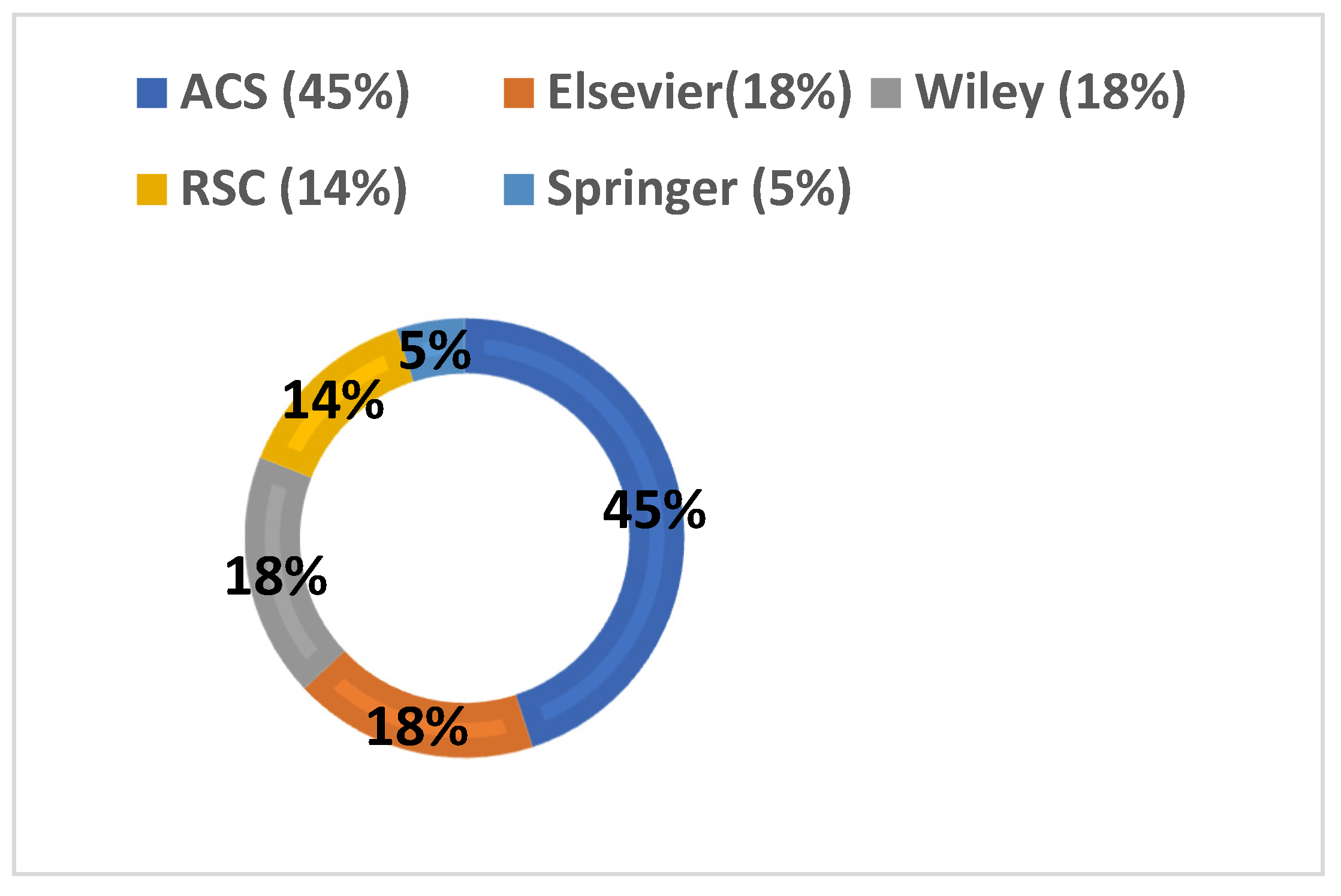

The disciplinary provenance of the TOC-ROLF samples analysed is quite homogeneous. Out of the 22 journals represented in the ten-month corpus, the majority was found to address the global chemistry community or to belong to broad subdisciplines, such as Inorganic and Organic Chemistry (

Figure 4). The established combined disciplines of Chemical Physics and Physical Chemistry (9% of corpus instances) and multidisciplinary journals (14%) covering a wide-ranging spectrum of (sub)disciplines at the interface of Materials Science, Chemistry, Engineering, Physics, Medicine and Biology yield not very disparate smaller proportions, as can be seen in the pie chart of

Figure 4. The titles of the journals in question are listed and sorted out by discipline in

Table 2, which shows an overwhelming presence of the ACS Publishing Center, followed in equal proportion by Elsevier and Wiley, and at a small distance by the Royal Society of Chemistry, based in the U.K. Springer Publishing, in contrast, trails behind with only one sample. A focus on the percentual weight of each publisher’s presence in the corpus is shown in

Figure 5.

Although the larger presence of a particular publisher (see

Table 2 and

Figure 5) might suggest vaguer instructions to authors, it is not necessarily so, as other factors may come into play, such as journal impact, reviewing times, percentages of rejection, or topic currency and centrality. Springer’s

Monatshefte für Chemie-Chemical Monthly, for example, is represented by one single sample and does not issue specific guidelines for GAs, just a ‘template for chemical drawings’ tackling aspects such as ‘line art’, ‘colour art’, ‘figure captions’, ‘figure lettering and numbering’, or ‘figure placement and size’.

The rest of publishers’ policies are more concrete and referred to GAs, also called ‘ToC image’, ‘ToC graphic/figure’, ‘ToC entry’, or ‘graphical ToC’ (ToC being the abbreviation for ‘table of contents’), yet specificity may increase in the guidelines for authors of each of their journals. ACS Publishing Center, nevertheless, just issues a set of general instructions accessible through a link in each of its journals and remarks that the graphic should be simple, informative and understood by someone who has not read the manuscript. It may consist in a structure, a graph, drawing, photo, scheme or a combination, and should avoid long phrases or sentences, as well as the inclusion of photographs and caricatures of any person, living or deceased. The use of colour is encouraged (an instruction shared by all publishers), and the standards of scholarly professional publications must be met, although they are not spelled out.

In its general guidelines, RSC includes a series of ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ that limit verbal text to 15–25 words and graphical elements to a maximum of two, recommending focusing only on key findings and using easily recognisable words that can be read quickly. Among the don’ts are the repetition of information present in the title and the use of graphs, spectra and too much detail. Its journal RSC Advances adds the specifications that the visual must comply with the principles of political correctness and not contain logos, trademarks or brand names, the text supplied must be one or two sentences long and comprise a maximum of 250 characters, and the graphic should ‘capture the reader’s attention’ (without any provision of compositional resources).

Wiley is the only publishing company that presents potential authors with the initiative of commissioning the GA to a professional in-house designer, and provides three exemplars respectively structured into one, two and three panels to show possible outcomes. Its general guidelines for authors detail the graphic’s dimensions, the type of file, copyright issues, and vaguely encourages selecting a figure that ‘best represents the scope of the paper’. More restrictive instructions are those issued by its journals: when dealing with political correctness, ChemCatChem and EurJOC allow recourse to elements of mythology, legends and folklore, which might be accepted on a case-by-case basis, but their policies discourage the use of religious iconography and imagery and of any object with a cultural significance. Chemistry. A European Journal discards, in addition, needless shading and asks authors to check the journal’s policy of colour use. The fourth of the Wiley journals, Small, demands that the accompanying verbal text does not exceed 60 words, is written in the third person and for a ‘general audience’, a rather fuzzy requisite within such a stringent condition.

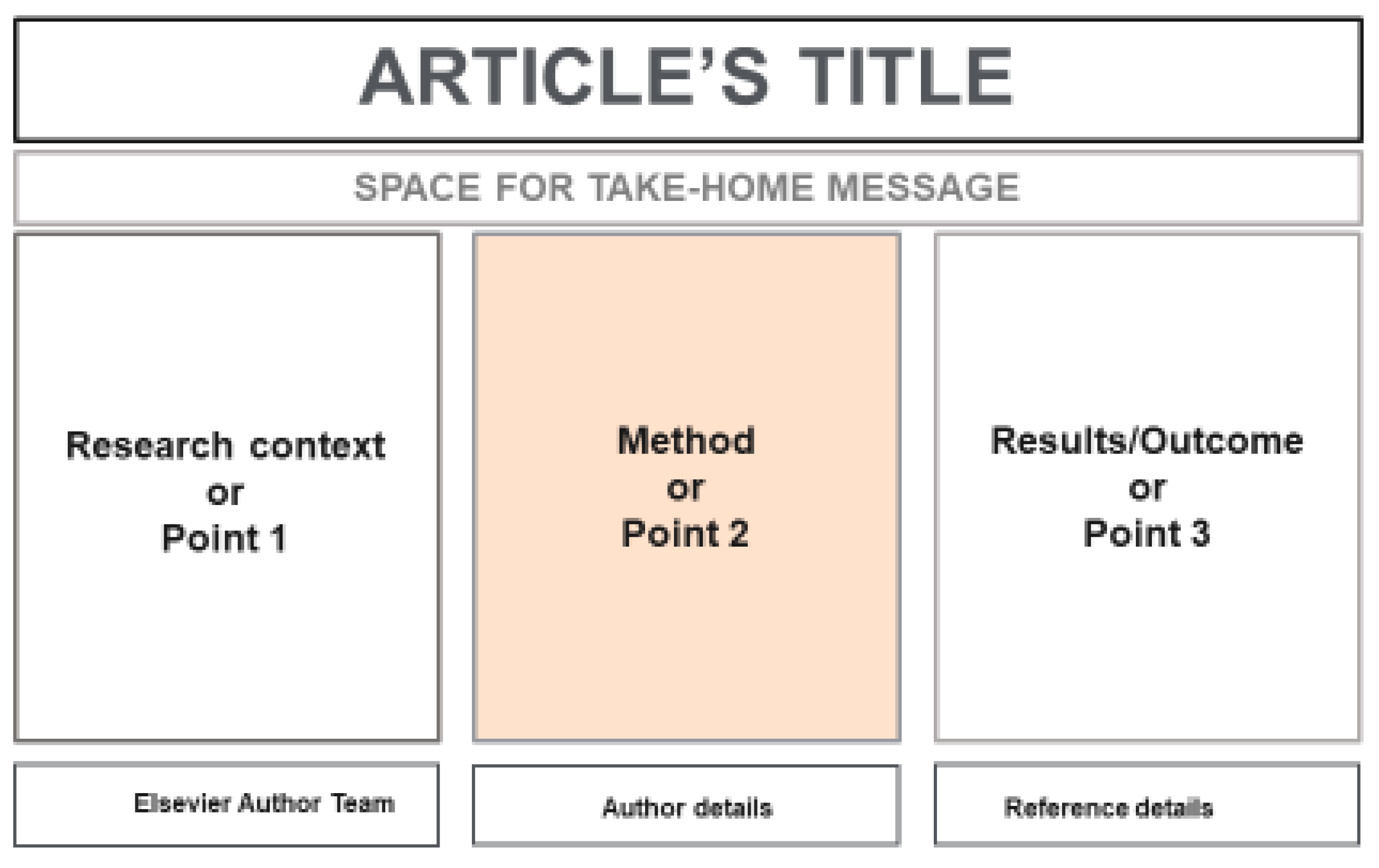

The four Elsevier samples in the corpus will surely have followed the guidelines for GAs in the publisher’s website until 2020. According to them, the visual should allow readers to ‘quickly gain an understanding of the main take-home message of the paper’, ‘encourage browsing’ and ‘promote interdisciplinary scholarship’. It is assumed to represent ‘the work described in the paper’ and adopt any of the compositional patterns found among the 16 exemplars shown online during the time span 2015–2020, whose basic typology is summarised in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

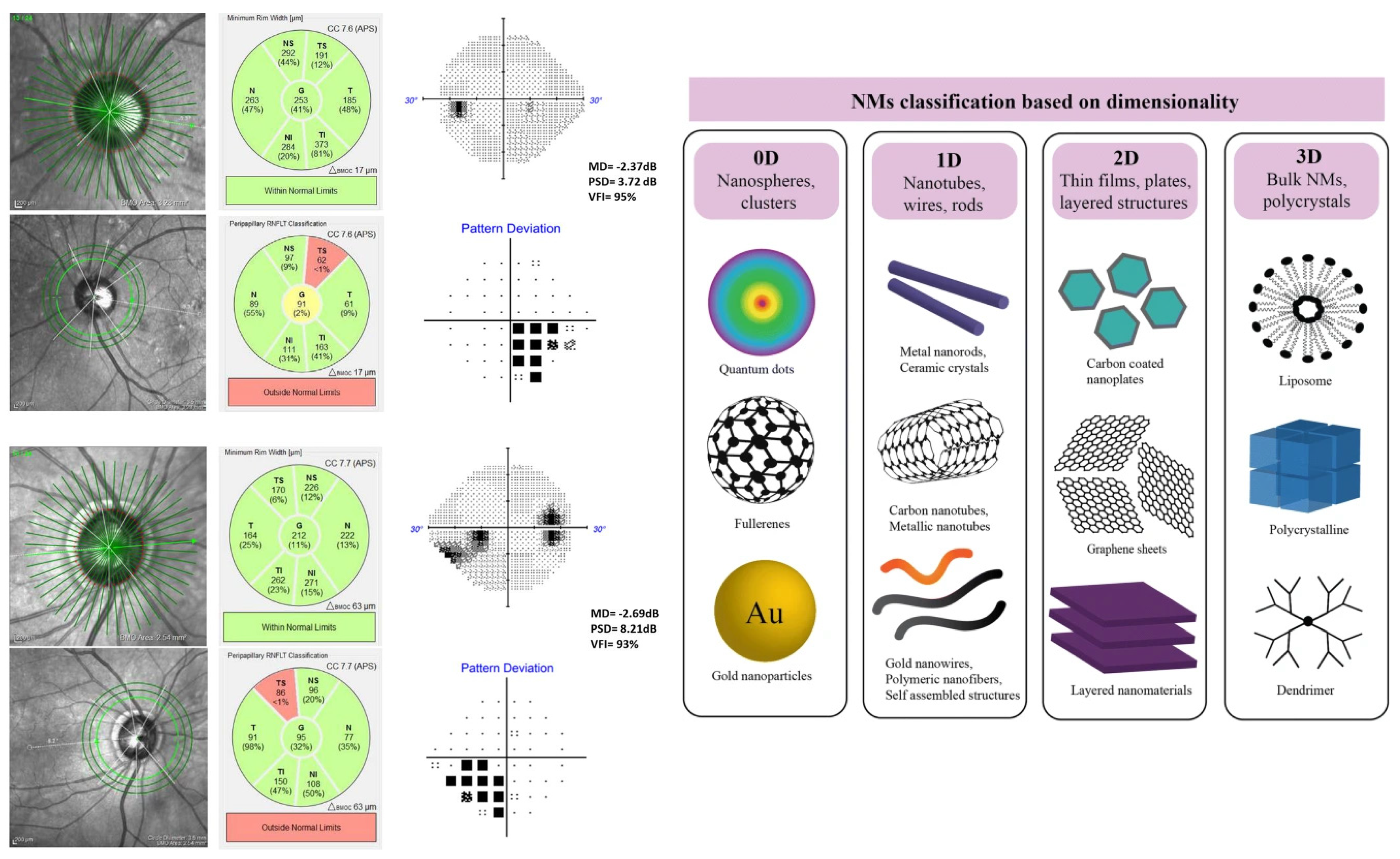

Figure 6 gathers three vectorial compositions based on the use of arrows (replaceable by lines). Vectors (here arrows) can be seen to perform three major functions: mark a narrative in which there has been some change in state or condition (i.e., differentiate a ‘before’ from an ‘after’), signal the reading or viewing path through the several stages of a process or procedure, and classify items from a superordinate category, indicating their derivation or exemplifying function.

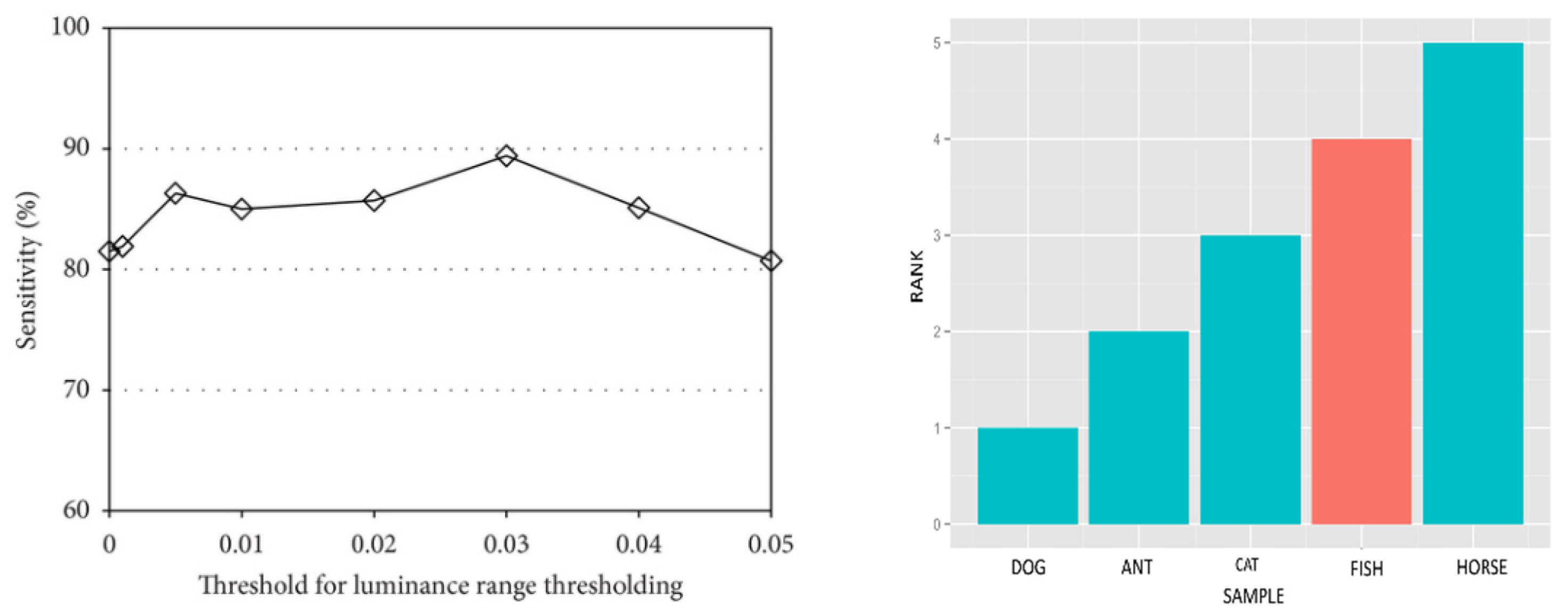

Visual displays of various sorts (

Figure 7) make up another frequent compositional pattern that entirely depends on editorial policies. Visual data in the form of graphs/charts and diagrams may appear as a minor element within a larger pattern or constitute a major one themselves, although such cases do not abound owing to the ever-increasing request for originality and creativity on the part of publishers and journal editors. This requirement tends to exclude the reproduction of graphics present in the article and to foster eye-catching compositions, but few journals caution against the risks of certain practices adopted for that purpose, such as colour saturation and cluttered visual arrangements. Elsevier’s

Cell is one of those few journals.

With or without vectors, the amplifications of detail, which I termed ‘zoom-ins’ in a previous work [

3], normally lean on collocational and framing resources and are reserved for the display of substructures or phenomena invisible to the naked eye. Both illustrations in

Figure 8 employ stylised lense icons as frames, but the mere collocation of an unframed finer-grained picture usually suffices to understand the visual progression.

Last but not least, classificatory arrangements through juxtaposed collocations and with or without verbal labels (

Figure 9) are an alternative to tree diagrams, although they may be mistaken for vectorless collocational narratives. The category or type, usually on top position, may be represented by a verbal label or a visual (labelled or not), below which subcategories and examples are placed. The same organisation may apply for progressive zoom-ins and narrative denouements in successive phases.

Since the beginning of 2021, Elsevier has changed its GA submission policy and demanded a unique compositional scheme consisting of three consecutive panels (see

Figure 10) for the rhetorical moves of ‘research contextualisation’, ‘methodology’ and ‘outcome’, in order to curb the insertion of extraneous material and subjective metaphorical conceptualisations and set more universal graphic conventions.

The idea is that readers/viewers grasp the article content ‘at a single glance’, but the four exemplars provided are not as lean as they should be for immediate visual capture. Only time will tell whether this goal will be eventually attained and whether modality markers and metaphorical embodiments will permeate the tripartite frame.