Face First: The Role of Age and Sex in the Epidemiology of Facial Fractures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

3. Results

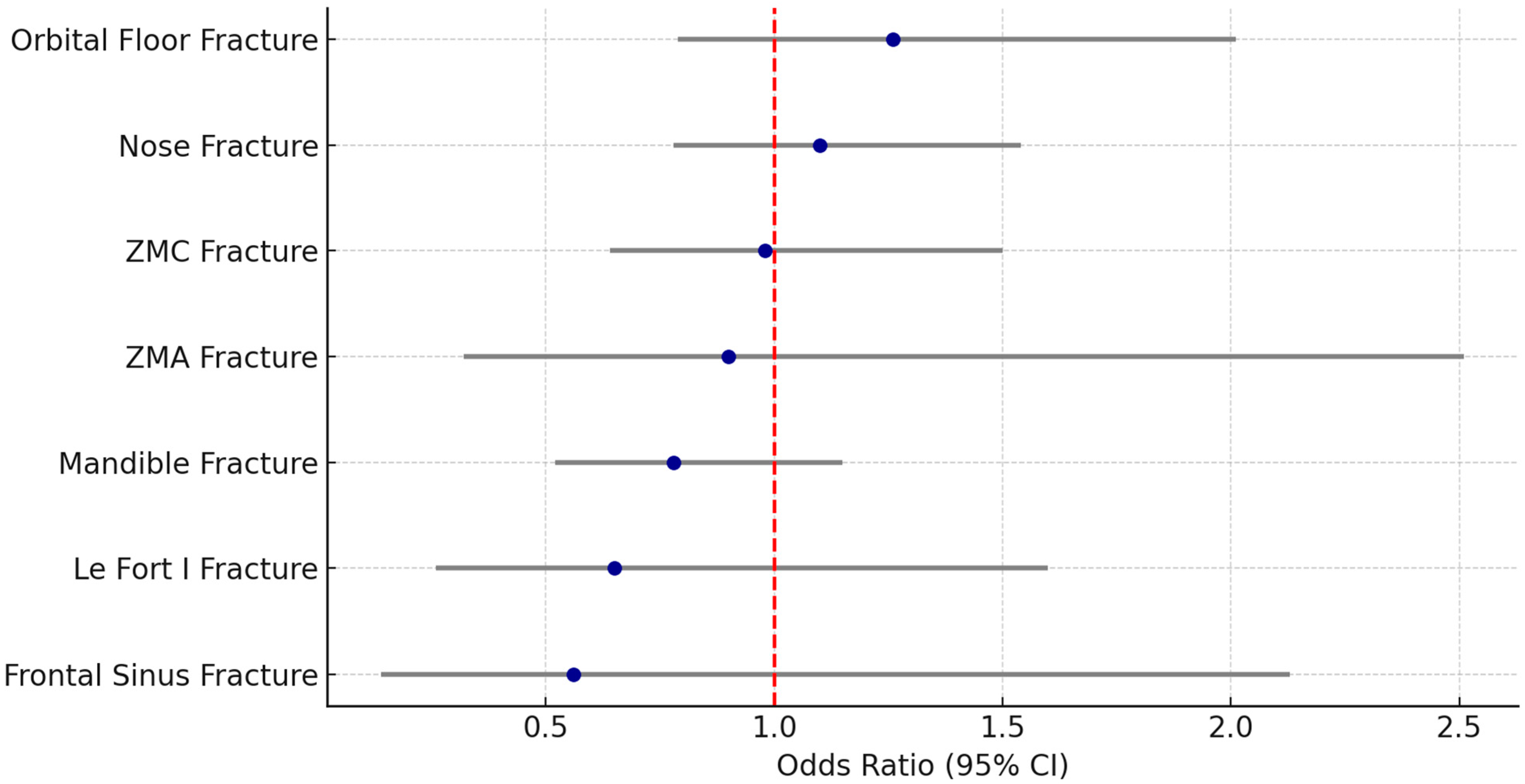

3.1. Analysis by Sex

3.2. Analysis by Age

4. Discussion

4.1. Sex-Based Differences

4.2. Age-Related Differences

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asya, O.; Gündoğdu, Y.; İnCaz, S.; Kavak, Ö.T.; Mammadli, J.; Özcan, S.; Çavlan, C.E.; Yumuşakhuylu, A.C. A retrospective epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures at a tertiary referral hospital in istanbul: A seven-year study of 1757 patients. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 46, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Girotto, J.A.; MacKenzie, E.; Fowler, C.; Redett, R.; Robertson, B.; Manson, P.N. Long-Term Physical Impairment and Functional Outcomes after Complex Facial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühnel, T.S.; Reichert, T.E. Trauma of the midface. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 14, Doc06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pappachan, B.; Alexander, M. Biomechanics of Cranio-Maxillofacial Trauma. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2012, 11, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, B.-H.; Han, S.-M.; Sun, T.; Guo, Z.; Cao, L.; Wu, H.-Z.; Shi, Y.-H.; Wen, J.-X.; Wu, W.-J.; Gao, B.-L. Dynamic changes of facial skeletal fractures with time. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoppe, I.C.; Kordahi, A.M.; Paik, A.M.; Lee, E.S.; Granick, M.S. Age and sex-related differences in 431 pediatric facial fractures at a level 1 trauma center. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1408–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-X.; Xie, L.; Li, Z. Global, regional, and national burdens of facial fractures: A systematic analysis of the global burden of Disease 2019. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Irgebay, Z.B.; Kahan, E.H.B.; Park, K.E.; Choi, J.; Zellner, E.G. Characteristics and Patterns of Facial Fractures in the Elderly Population in the United States Based on Trauma Quality Improvement Project Data. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2022, 33, 1294–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diab, J.; Moore, M.H. Patterns and characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in women. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 27, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sheikh, S.; Chokotho, L.; Mulwafu, W.; Nyirenda, M.; Le, G.; Mbomuwa, F.; Pandit, H.; Lavy, C. Characteristics of interpersonal violence in adult victims at the Adult Emergency Trauma Centre (AETC) of Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital. Malawi Med. J. 2020, 32, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rivis, M.; Juncar, R.I.; Moca, A.E.; Moca, R.T.; Juncar, M.; Ţenţ, P.A. Patterns of Mandibular Fractures through Human Aggression: A 10-Year Cross-Sectional Cohort Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, F.C.; Halsey, J.N.; Oleck, N.C.; Lee, E.S.; Granick, M.S. Facial Fractures as a Result of Falls in the Elderly: Concomitant Injuries and Management Strategies. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H.; Araya-Quintanilla, F.; Olguín-Huerta, C.; Gutiérrez-Monclus, R.; Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.; Román-Veas, J.; Campos-Jara, C. Effectiveness of surgical versus conservative treatment of distal radius fractures in elderly patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2022, 108, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.-Y.; Bajani, F.; Bokhari, M.; Starr, F.; Messer, T.; Kaminsky, M.; Dennis, A.; Schlanser, V.; Mis, J.; Poulakidas, S.; et al. Age itself or age-associated comorbidities? A nationwide analysis of outcomes of geriatric trauma. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 2873–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soares-Carneiro, S.; Vasconcelos, B.; Da-Silva, G.M.; De-Barros-Caldas, L.; Porto, G.; Leal, J.; Catunda, I. Alcohol abusive use increases facial trauma? Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e547–e553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Porto, G.G.; de Menezes, L.P.; Cavalcante, D.K.F.; de Souza, R.R.L.; Carneiro, S.C.d.A.S.; Antunes, A.A. Do Type of Helmet and Alcohol Use Increase Facial Trauma Severity? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 797.e1–797.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, H.; Talemal, L.; Moss, C.; Araya, S.; Kozorosky, E.; Patel, S.A.; Walchak, A. Epidemiology and Characteristics of Women With Facial Fractures Seeking Emergency Care in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, NP82–NP89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costa, M.C.F.; Cavalcante, G.M.S.; da Nóbrega, L.M.; Oliveira, P.A.P.; Cavalcante, J.R.; D’aVila, S. Facial traumas among females through violent and non-violent mechanisms. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 80, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hwang, K.; You, S.H. Analysis of facial bone fractures: An 11-year study of 2,094 patients. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2010, 43, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Hassani, A.; Ahmad, K.; El-Menyar, A.; Abutaka, A.; Mekkodathil, A.; Peralta, R.; Al Khalil, M.; Al-Thani, H. Prevalence and patterns of maxillofacial trauma: A retrospective descriptive study. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 2513–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’meara, C.; Witherspoon, R.; Hapangama, N.; Hyam, D. Mandible fracture severity may be increased by alcohol and interpersonal violence. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, C.R.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors for falls in older men and women: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freigang, V.; Müller, K.; Ernstberger, A.; Alt, V.; Herrmann-Johns, A.; Baumann, F. Sex-Specific Factors Affecting Quality of Life After Major Trauma: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Registry-Based Cohort Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zimmermann-Sloutskis, D.; Wanner, M.; Zimmermann, E.; Martin, B.W. Physical activity levels and determinants of change in young adults: A longitudinal panel study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.-Y.; Jin, K. Age-Related Dysfunction in Balance: A Comprehensive Review of Causes, Consequences, and Interventions. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 714–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fukada, K.; Kajiya, K. Age-related structural alterations of skeletal muscles and associated capillaries. Angiogenesis 2020, 23, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, A.; Liew, S.; Weinkle, S.; Garcia, J.K.; Silberberg, M.B. The Facial Aging Process From the “Inside Out”. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2021, 41, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaishya, R.; Vaish, A. Falls in Older Adults are Serious. Indian J. Orthop. 2020, 54, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turke, P.W. Five reasons COVID-19 is less severe in younger age-groups. Evol. Med. Public Health 2020, 9, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clark, D.; Nakamura, M.; Miclau, T.; Marcucio, R. Effects of Aging on Fracture Healing. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Male (n = 337) | Female (n = 224) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.19 (±24.43) | 45.55 (±21.51) | 64.67 (±24.12) | <0.001 |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 337 (60.1%) | 337 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Female | 224 (39.9%) | 0 (0%) | 224 (100%) |

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Male (n = 337) | Female (n = 224) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandible Fracture | 141 (25.1%) | 91 (27.0%) | 50 (22.3%) | 0.78 | 0.52–1.15 | 0.211 |

| Nose Fracture | 255 (45.5%) | 150 (44.5%) | 105 (46.9%) | 1.10 | 0.78–1.54 | 0.582 |

| ZMC Fracture | 109 (19.4%) | 66 (19.6%) | 43 (19.2%) | 0.98 | 0.64–1.50 | 0.909 |

| Isolated Orbital Floor Fracture | 85 (15.2%) | 47 (13.9%) | 38 (17.0%) | 1.26 | 0.79–2.01 | 0.329 |

| Isolated ZMA Fracture | 16 (2.9%) | 10 (3.0%) | 6 (2.7%) | 0.90 | 0.32–2.51 | 0.841 |

| Le Fort I Fracture | 23 (4.1%) | 16 (4.7%) | 7 (3.1%) | 0.65 | 0.26–1.60 | 0.342 |

| Le Fort II Fracture | 7 (1.2%) | 7 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | / * | / * | 0.030 |

| Le Fort III Fracture | 3 (0.5%) | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | / * | / * | 0.157 |

| Frontal Sinus fracture | 11 (2.0%) | 8 (2.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.56 | 0.14–2.13 | 0.387 |

| Panfacial fracture | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | / * | / * | 0.414 |

| Operation | 231 (41.2%) | 164 (48.7%) | 67 (29.9%) | 0.45 | 0.32–0.64 | <0.001 |

| Conservative Treatment | 330 (58.8%) | 173 (51.3%) | 157 (70.1%) | 2.22 | 1.55–3.17 | <0.001 |

| (a) | ||||||

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Male (n = 337) | Female (n = 224) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

| Fall | 199 (35.5%) | 89 (26.4%) | 110 (49.1%) | 4.62 | 3.21–6.66 | <0.001 |

| Sports accident | 63 (11.2%) | 53 (15.7%) | 10 (4.5%) | 0.47 | 0.29–0.77 | 0.002 |

| Syncope | 36 (6.4%) | 12 (3.6%) | 24 (10.7%) | 2.17 | 1.24–3.80 | 0.006 |

| Road Traffic accident (including car, motorcycle, bike, e-scooter) | 111 (19.8%) | 70 (20.8%) | 41 (18.3%) | 0.85 | 0.56–1.31 | 0.472 |

| Interpersonal violence | 152 (27.1%) | 130 (38.6%) | 22 (9.8%) | 0.17 | 0.11–0.28 | <0.001 |

| (b) | ||||||

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Male (n = 337) | Female (n = 224) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

| Accident at home | 179 (31.9%) | 100 (29.7%) | 79 (35.3%) | 1.29 | 1.12–1.95 | 0.016 |

| Alcohol related trauma | 121 (21.6%) | 95 (28.2%) | 26 (11.6%) | 0.34 | 0.21–0.54 | <0.001 |

| Work related accident | 56 (10.0%) | 47 (13.9%) | 9 (4.0%) | 0.35 | 0.17–0.74 | <0.001 |

| Free time accident | 505 (90.0%) | 290 (86.1%) | 215 (96.0%) | 3.87 | 1.86–8.07 | <0.001 |

| Weekday | 294 (52.4%) | 178 (52.8%) | 116 (51.8%) | 0.96 | 0.68–1.35 | 0.810 |

| Weekend | 267 (47.6%) | 159 (47.2%) | 108 (48.2%) | 1.04 | 0.74–1.46 | 0.810 |

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Age > 50 Years (n = 276) | Age < 50 Years (n = 285) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.19 (±24.43) | 75.00 (±14.42) | 32.06 (±8.11) | <0.001 |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 337 (60.1%) | 118 (48.2%) | 219 (76.8%) | |

| Female | 224 (39.9%) | 158 (57.2%) | 66 (23.2%) |

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Age < 50 Years (n = 285) | Age > 50 Years (n = 276) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandible Fracture | 141 (25.1%) | 85 (29.8%) | 56 (20.3%) | 0.59 | 0.40–0.88 | 0.009 |

| Nose Fracture | 255 (45.5%) | 126 (44.2%) | 129 (46.7%) | 1.11 | 0.79–1.54 | 0.548 |

| ZMC Fracture | 109 (19.4%) | 54 (18.9%) | 55 (19.9%) | 1.06 | 0.70–1.62 | 0.769 |

| Isolated Orbital Floor Fracture | 85 (15.2%) | 39 (13.7%) | 46 (16.7%) | 1.26 | 0.79–2.00 | 0.325 |

| Isolated ZMA Fracture | 16 (2.9%) | 5 (1.8%) | 11 (4.0%) | 2.33 | 0.79–6.78 | 0.112 |

| Le Fort I Fracture | 23 (4.1%) | 11 (3.9%) | 12 (4.3%) | 1.13 | 0.49–2.61 | 0.771 |

| Le Fort II Fracture | 7 (1.2%) | 2 (0.7%) | 5 (1.8%) | 2.61 | 0.50–13.57 | 0.236 |

| Le Fort III Fracture | 3 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.1%) | n.a. * | n.a. * | 0.078 |

| Frontal Sinus fracture | 11 (2.0%) | 2 (0.7%) | 9 (3.3%) | 4.77 | 1.02–22.27 | 0.029 |

| Panfacial fracture | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | n.a. * | n.a. * | 0.309 |

| Operation | 231 (41.2%) | 133 (46.7%) | 98 (35.5%) | 0.63 | 0.45–0.88 | 0.007 |

| Conservative Treatment | 330 (58.8%) | 152 (53.3%) | 178 (64.5%) | 1.59 | 1.13–2.23 | 0.007 |

| (a) | ||||||

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Age < 50 Years (n = 285) | Age > 50 Years (n = 276) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

| Fall | 199 (35.5%) | 66 (23.2%) | 133 (48.1%) | 9.95 | 6.75–14.66 | <0.001 |

| Sports accident | 63 (11.2%) | 49 (17.2%) | 14 (5.1%) | 0.38 | 0.24–0.61 | <0.001 |

| Syncope | 36 (6.4%) | 8 (2.8%) | 28 (10.1%) | 3.14 | 1.69–5.82 | <0.001 |

| Road Traffic accident (including car, motorcycle, bike, e-scooter) | 111 (19.8%) | 59 (20.7%) | 52 (18.8%) | 0.89 | 0.59–1.35 | 0.580 |

| Interpersonal violence | 152 (27.1%) | 103 (36.1%) | 49 (17.8%) | 0.04 | 0.02–0.08 | <0.001 |

| (b) | ||||||

| Variable | Total (n = 561) | Age < 50 Years (n = 285) | Age > 50 Years (n = 276) | OR | CI (95%) | p-Value |

| Accident at home | 179 (31.9%) | 84 (29.5%) | 95 (34.4%) | 1.26 | 0.88–1.79 | 0.209 |

| Alcohol related trauma | 121 (21.6%) | 106 (37.2%) | 15 (5.4%) | 0.09 | 0.05–0.17 | <0.001 |

| Work related accident | 56 (10.0%) | 39 (13.7%) | 17 (6.2%) | 0.58 | 0.22–0.88 | 0.003 |

| Free time accident | 505 (90.0%) | 246 (86.3%) | 259 (93.8%) | 2.42 | 1.33–4.38 | 0.003 |

| Weekday | 294 (52.4%) | 130 (45.6%) | 164 (59.4%) | 1.75 | 1.25–2.44 | 0.001 |

| Weekend | 267 (47.6%) | 155 (54.4%) | 112 (40.6%) | 0.57 | 0.41–0.80 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aydin, A.; Revend, L.; Revend, D.; Giese, M.; Schuck, O.; Roj, S.; Schunk, J.; Dudde, F. Face First: The Role of Age and Sex in the Epidemiology of Facial Fractures. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010004

Aydin A, Revend L, Revend D, Giese M, Schuck O, Roj S, Schunk J, Dudde F. Face First: The Role of Age and Sex in the Epidemiology of Facial Fractures. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Anna, Lawik Revend, Doha Revend, Manfred Giese, Oliver Schuck, Stephanie Roj, Johannes Schunk, and Florian Dudde. 2026. "Face First: The Role of Age and Sex in the Epidemiology of Facial Fractures" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010004

APA StyleAydin, A., Revend, L., Revend, D., Giese, M., Schuck, O., Roj, S., Schunk, J., & Dudde, F. (2026). Face First: The Role of Age and Sex in the Epidemiology of Facial Fractures. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010004