Comparative Wear of Opposing Natural Enamel by Different Ceramic Materials in Fixed Dental Protheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. PICO Question

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Collection Process

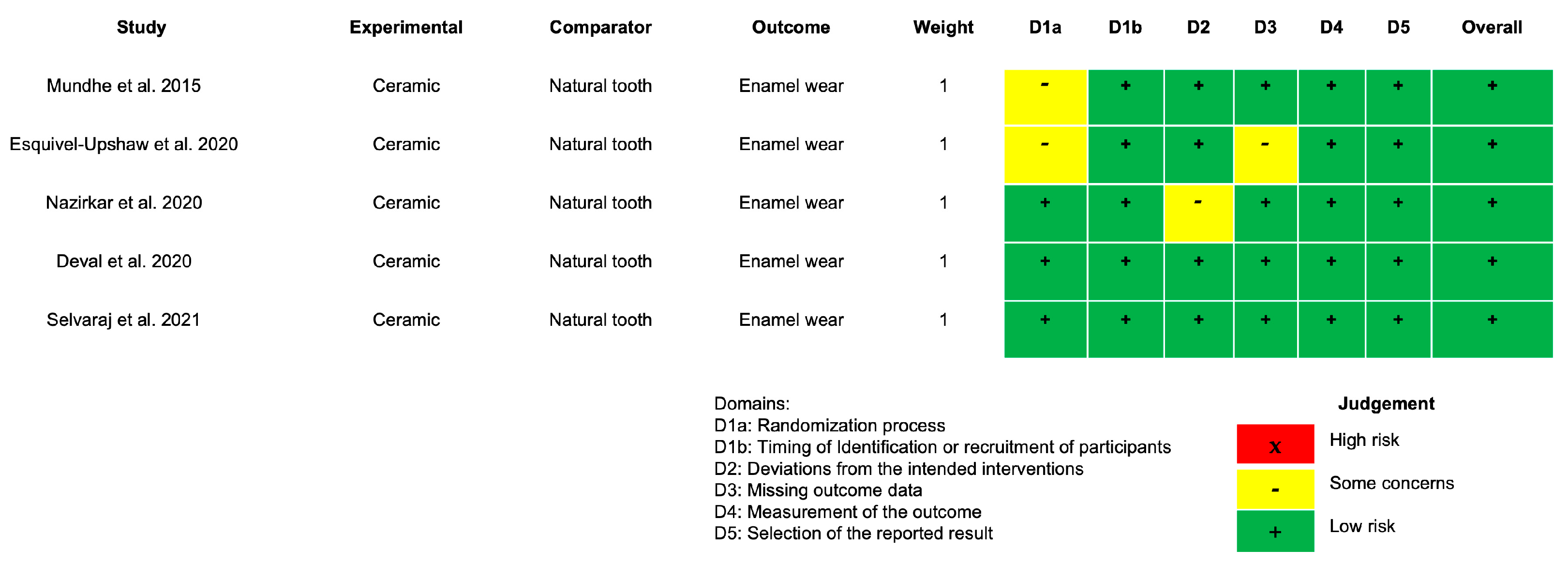

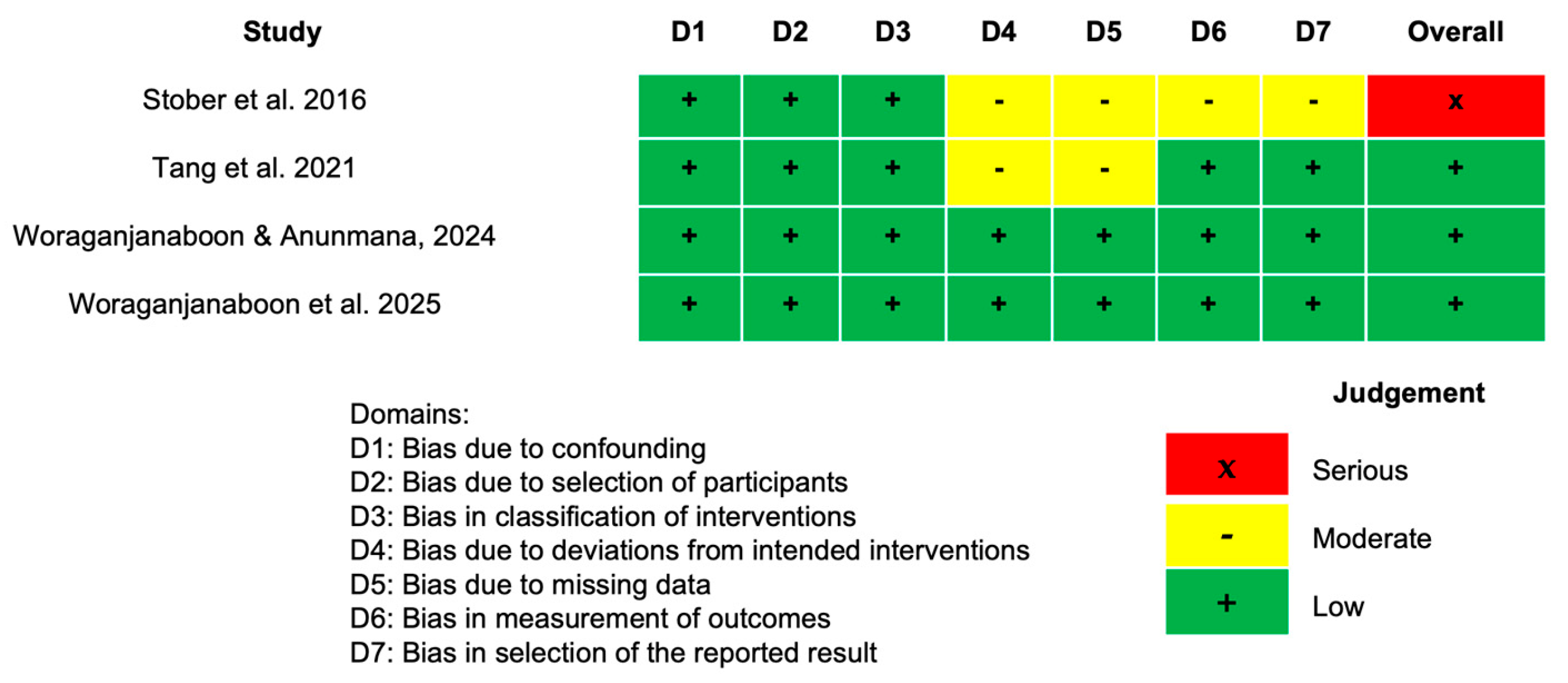

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Meta-Analysis

2.9. Additional Analysis

3. Results

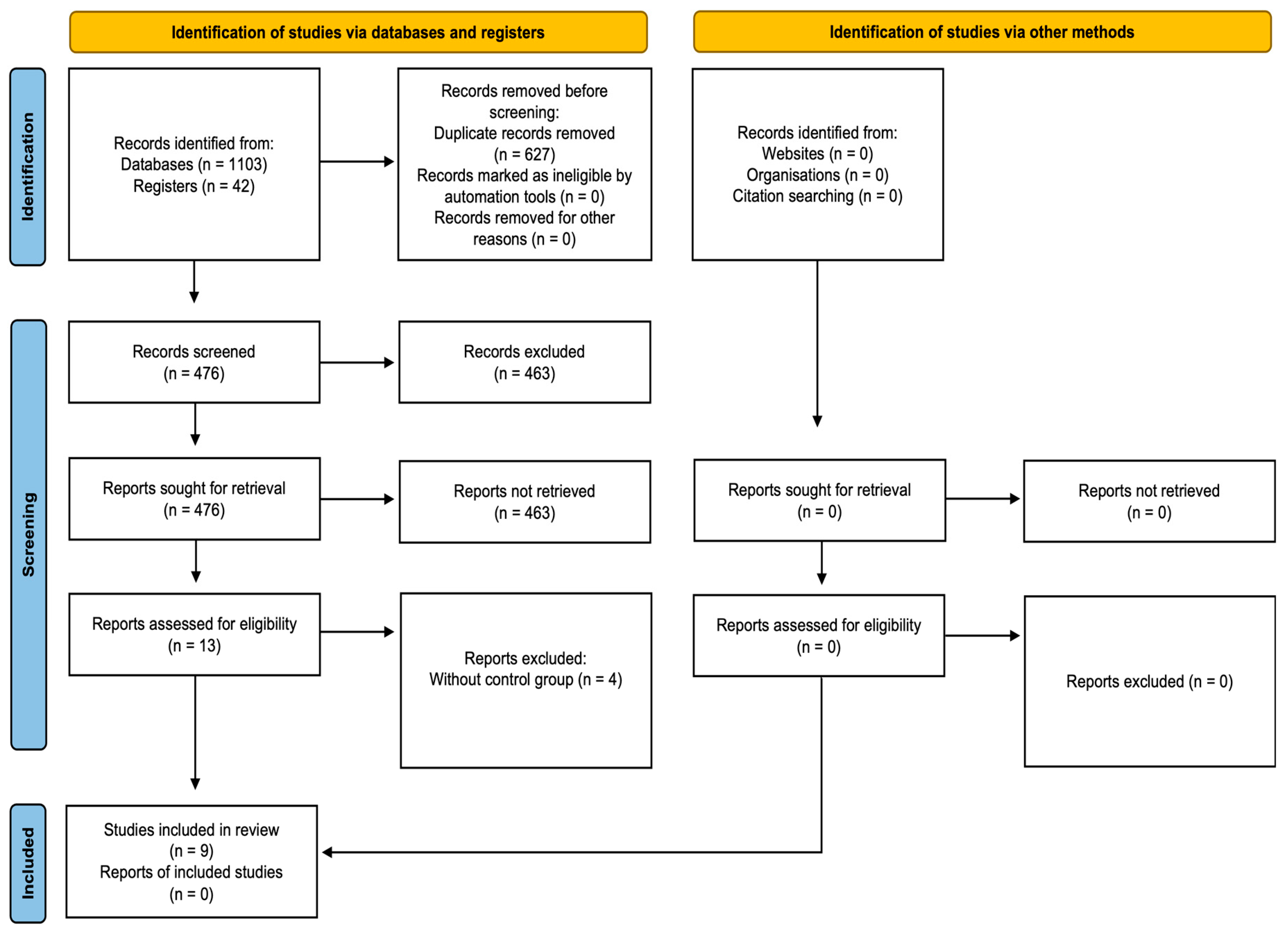

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias

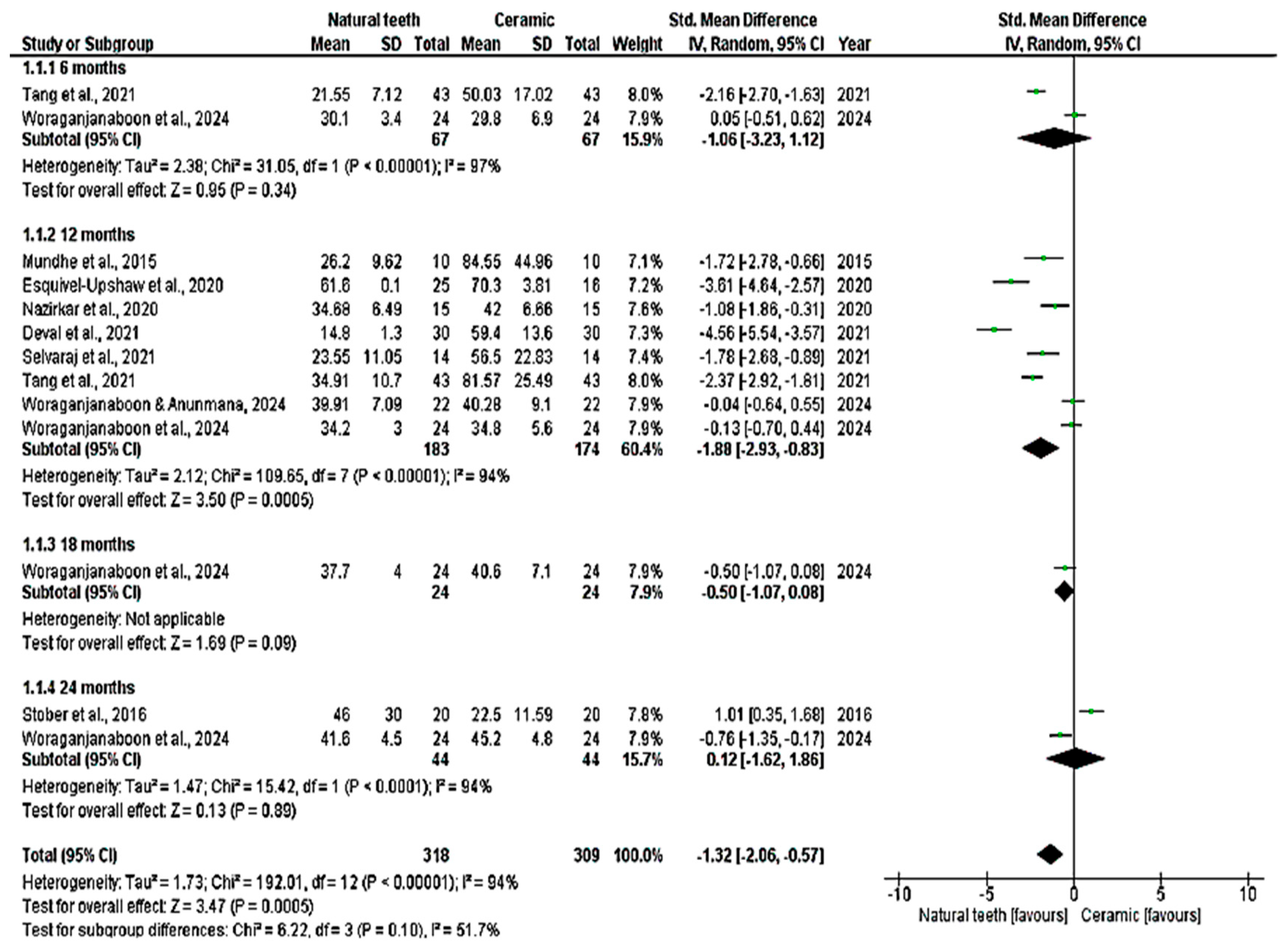

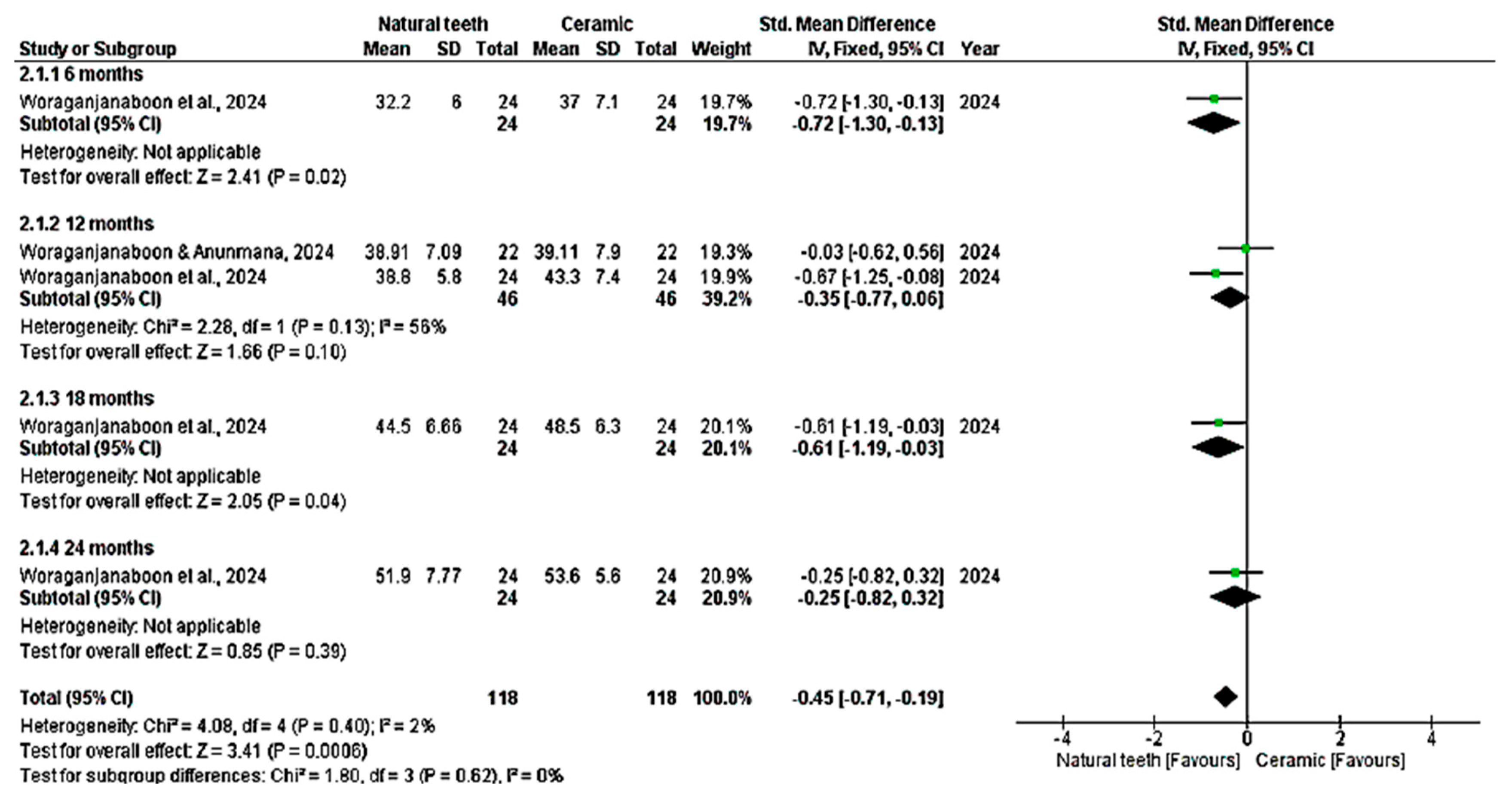

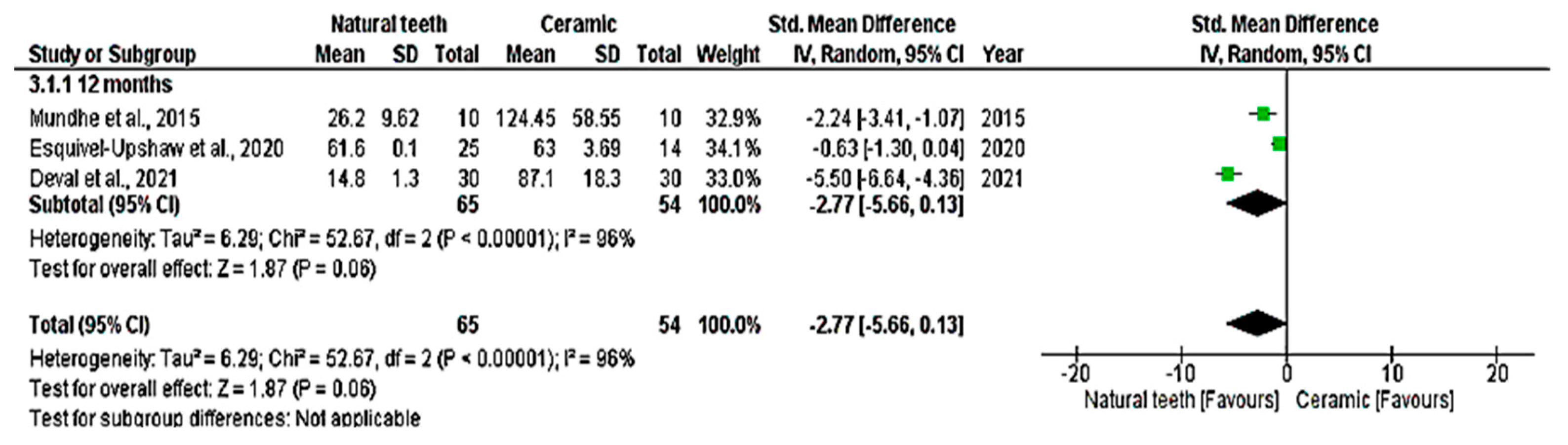

3.4. Meta-Analysis

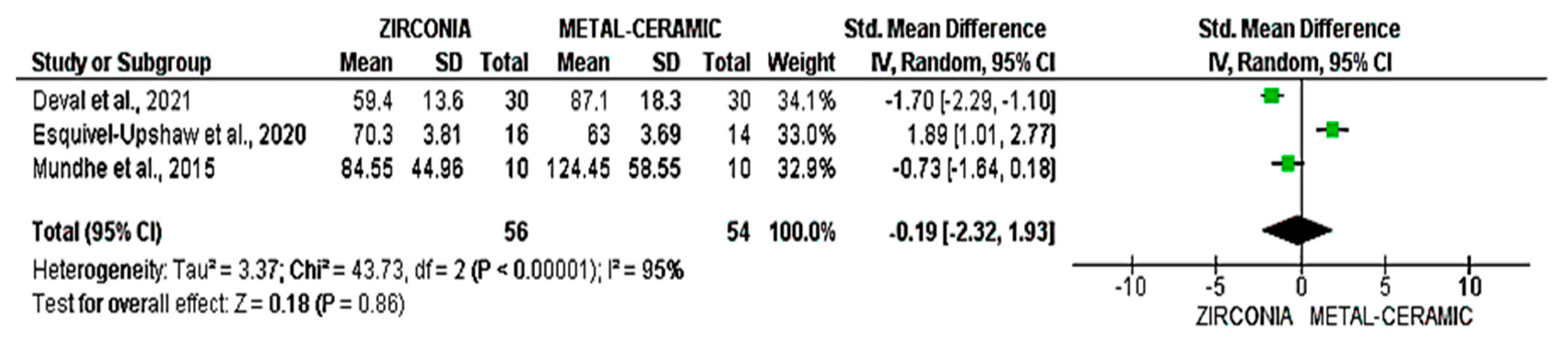

3.5. Additional Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trial |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| IV | Inverse Variance |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| RoB 2.0 | Risk of Bias 2.0 |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions |

| Zr | Zirconia |

| L | Lithium disilicate |

| MC | Metal-ceramic prosthesis |

| NR | Not reported |

| F | Female |

| M | Male |

| CAD-CAM | Computer-Aided Design and Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| Y-TZP | Yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal |

References

- Aljomard, Y.R.M.; Altunok, E.Ç.; Kara, H.B. Enamel wear against monolithic zirconia restorations: A meta-analysis and systematic review of in vitro studies. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kok, P.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; de Jager, N.; Kuijs, R.; Feilzer, A.J. Mechanical performance of implant-supported posterior crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmaidouch, R.; Weigl, P. Tooth wear against ceramic crowns in posterior region: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 5, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLong, R. Intra-oral restorative materials wear: Rethinking the current approaches: How to measure wear. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Velastegui, M.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Fons-Badal, C.; Solá-Ruíz, M.F. Enamel Wear of Antagonist Tooth Caused by Dental Ceramics: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, P.; Braem, M.; Vuylsteke-Wauters, M.; Vanherle, G. Quantitative in vivo wear of human enamel. J. Dent. Res. 1989, 68, 1752–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Patil, N.P.; Patil, S.B. The abrasive effect of a porcelain and a nickel-chromium alloy on the wear of human enamel and the influence of a carbonated beverage on the rate of wear. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 19, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Ju, S.W.; Seo, D.G.; Jun, S.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Ryu, J.J. Wear evaluation of the human enamel opposing different Y-TZP dental ceramics and other porcelains. J. Dent. 2012, 40, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripetchdanond, J.; Leevailoj, C. Wear of human enamel opposing monolithic zirconia, glass ceramic, and composite resin: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, J.; Taira, Y.; Sawase, T. In vitro wear of four ceramic materials and human enamel on enamel antagonist. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 124, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Upshaw, J.F.; Kim, M.J.; Hsu, S.M.; Abdulhameed, N.; Jenkins, R.; Neal, D.; Ren, F.; Clark, A.E. Randomized clinical study of wear of enamel antagonists against polished monolithic zirconia crowns. J. Dent. 2018, 68, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaoka, A.; Akatsuka, R.; Kato, H.; Yoda, N.; Sasaki, K. Clinical Evaluation of Monolithic Zirconia Crowns: A Short-Term Pilot Report. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solá-Ruíz, M.F.; Baima-Moscardó, A.; Selva-Otaolaurruchi, E.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Fons-Badal, C.; Fernández-Estevan, L. Wear in Antagonist Teeth Produced by Monolithic Zirconia Crowns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquivel-Upshaw, J.F.; Hsu, S.M.; Bohórquez, A.C.; Abdulhameed, N.; Scheiffele, G.W.; Kim, M.; Neal, D.; Chai, J.; Ren, F. Novel methodology for measuring intraoral wear in enamel and dental restorative materials. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2020, 6, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, S.P.; Torrealba, Y.; Major, P.; Linke, B.; Flores-Mir, C.; Nychka, J.A. In vitro wear behavior of zirconia opposing enamel: A systematic review. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, M.; Chen, H.; Kang, J.; Wang, H. Antagonist enamel wear of tooth-supported monolithic zirconia posterior crowns in vivo: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Cavalleri, A.; Forjanic, M.; Zellweger, G.; Rousson, V. Wear of ceramic and antagonist—A systematic evaluation of influencing factors in vitro. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartkamp, O.; Lohbauer, U.; Reich, S. Antagonist wear by polished zirconia crowns. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2017, 20, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lohbauer, U.; Reich, S. Antagonist wear of monolithic zirconia crowns after 2 years. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathan, M.S.; Kheur, M.G.; Patankar, A.H.; Kheur, S.M. Assessment of antagonist enamel wear and clinical performance of full-contour monolithic zirconia crowns: One-year results of a prospective study. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e411–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solá-Ruiz, M.F.; Baixauli-López, M.; Roig-Vanaclocha, A.; Amengual-Lorenzo, J.; Agustín-Panadero, R. Prospective study of monolithic zirconia crowns: Clinical behavior and survival rate at a 5-year follow-up. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundhe, K.; Jain, V.; Pruthi, G.; Shah, N. Clinical study to evaluate the wear of natural enamel antagonist to zirconia and metal ceramic crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stober, T.; Bermejo, J.L.; Schwindling, F.S.; Schmitter, M. Clinical assessment of enamel wear caused by monolithic zirconia crowns. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazirkar, G.S.; Patil, S.V.; Shelke, P.P.; Mahagaonkar, P. Comparative evaluation of natural enamel wear against polished yitrium tetragonal zirconia and polished lithium disilicate—An in vivo study. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2020, 20, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Deval, P.; Tembhurne, J.; Gangurde, A.; Chauhan, M.; Jaiswal, N.; Tiwari, D.K. A Clinical Comparative Evaluation Of The Wear Of Enamel Antagonist To Monolithic Zirconia And Metal-Ceramic Crowns. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, U.; Koli, D.K.; Jain, V.; Nanda, A. Evaluation of the wear of glazed and polished zirconia crowns and the opposing natural teeth: A clinical pilot study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H. Quantitative analysis on the wear of monolithic zirconia crowns on antagonist teeth. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woraganjanaboon, P.; Anunmana, C. 3D quantitative analysis and SEM qualitative analysis of natural antagonist enamel opposing CAD-CAM monolithic zirconia or lithium disilicate tooth-supported crowns versus enamel opposing natural enamel. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2024, 16, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woraganjanaboon, P.; Senawongse, P.; Anunmana, C. A two-year clinical trial of enamel wear opposing 5Y-TZP and lithium disilicate crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | Search Terms |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | #1 | ((((((“fixed prosthodontics”)) OR (“fixed dental prosthesis”)) OR (“crown-tooth”)) OR (“tooth preparation”)) OR (“crown preparation”)) OR (“full crown preparation”)) OR (“full coverage restorations”) |

| #2 | (((((“ceramics”)) OR (“monolithic zirconia”) OR (“lithium disilicate”)) OR (“feldspathic”)) OR (“metal ceramic”) | |

| #3 | (((“tooth wear”)) OR (“occlusal wear”)) OR (“enamel wear”) | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| Web of Science | #1 | ((((((ALL=(“fixed prosthodontics”)) OR ALL=(“fixed dental prosthesis”)) OR ALL=(“crown-tooth”)) OR ALL=(“tooth preparation”)) OR ALL=(“crown preparation”)) OR ALL=(“full crown preparation”)) OR ALL=(“full coverage restorations”) |

| #2 | (((((“ceramics”)) OR (“monolithic zirconia”) OR (“lithium disilicate”)) OR (“feldspathic”)) OR (“metal ceramic”) | |

| #3 | (((ALL= (“tooth wear”)) OR ALL=(“occlusal wear”)) OR ALL=(“enamel wear”) | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| Embase | #1 | ((((((“fixed prosthodontics”)) OR (“fixed dental prosthesis”)) OR (“crown-tooth”)) OR (“tooth preparation”)) OR (“crown preparation”)) OR (“full crown preparation”)) OR (“full coverage restorations”) |

| #2 | (((((“ceramics”)) OR (“monolithic zirconia”) OR (“lithium disilicate”)) OR (“feldspathic”)) OR (“metal ceramic”) | |

| #3 | (((“tooth wear”)) OR (“occlusal wear”)) OR (“enamel wear”) | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| Cochrane | #1 | ((((((“fixed prosthodontics”)) OR (“fixed dental prosthesis”)) OR (“crown-tooth”)) OR (“tooth preparation”)) OR (“crown preparation”)) OR (“full crown preparation”)) OR (“full coverage restorations”) |

| #2 | (((((“ceramics”)) OR (“monolithic zirconia”) OR (“lithium disilicate”)) OR (“feldspathic”)) OR (“metal ceramic”) | |

| #3 | (((“tooth wear”)) OR (“occlusal wear”)) OR (“enamel wear”) | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| ProQuest | #1 | (((((noft=(“fixed prosthodontics”)) OR (“fixed dental prosthesis”)) OR (“crown-tooth”)) OR (“tooth preparation”)) OR (“crown preparation”)) OR (“full crown preparation”)) OR (“full coverage restorations”) |

| #2 | ((((noft=(“ceramics”)) OR (“monolithic zirconia”) OR (“lithium disilicate”)) OR (“feldspathic”)) OR (“metal ceramic”) | |

| #3 | ((noft=(“tooth wear”)) OR (“occlusal wear”)) OR (“enamel wear”) | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Author and Year | Design | Patients | Age (Years) | Crown Position | Material of Ceramic | Follow-Up (Months) | Wear Results (Mean ± SD) | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel × Enamel (µm) | Enamel × Ceramic (µm) | ||||||||

| Mundhe et al., 2015 [25] | RCT | 10 NR | 18–35 | Molar and Premolar | Zr MC | 12 | 26.2 ± 9.62 | Zr 84.55 ± 44.96 Mc 124.45 ± 58.55 | Zirconia crowns led to less wear of antagonist enamel than metal ceramic crowns, but more than natural enamel. |

| Stober et al., 2016 [26] | Prospective | 10 M 10 F | 21–73 | Molar | Zr | 6, 12, 24 | 6 months: NR 12 months: NR 24 months: 46 ± 30 | 6 months: NR 12 months: NR 24 months: 22.5 ± 11.59 | Monolithic zirconia crowns generated more wear of opposed enamel than did natural teeth. |

| Esquivel-Upshaw et al., 2020 [14] | RCT | 5 M 20 F | >21 | Molar and Premolar | Zr MC | 6 and 12 | 6 months: NR 12 months: 61.6 ± 0 | Zr 6 months: NR 12 months: 70.3 ± 3.81 MC 6 months: NR 12 months: 63 ± 3.69 | Monolithic zirconia exhibited comparable wear of enamel compared with metal-ceramic crowns and control enamel after one year. |

| Nazirkar et al., 2020 [27] | RCT | 15 NR | 20–40 | Molar | Zr | 12 | 34.68 ± 6.49 | 42 ± 6.66 | Natural enamel wear is significantly more against zirconia crowns as compared to the natural antagonist. |

| Deval et al., 2021 [28] | RCT | 30 NR | 18–40 | Molar | Zr MC | 12 | 14.8 ± 1.3 | Zr 59.4 ± 13.6 MC 87.1 ± 18.3 | Wear of natural enamel opposing metal-ceramic and zirconia crowns was significantly higher than wear of natural enamel opposing natural teeth. |

| Selvaraj et al., 2021 [29] | RCT | 14 NR | 18–45 | Molar and Premolar | Zr | 12 | 23.55 ± 11.05 | 56.5 ± 22.83 | Monolithic zirconia crowns cause more wear on the opposing natural enamel than on the natural enamel antagonists. |

| Tang et al., 2021 [30] | Prospective | 22 M 21 F | ±42.2 | Molar and Premolar | Zr | 6 and 12 | 6 months: 21.55 ± 7.12 12 months: 34.91 ± 10.7 | 6 months: 50.03 ± 17.02 12 months: 81.57 ± 25.49 | The monolithic zirconia crown can cause more wear than natural teeth and will increase over time. |

| Woraganjanaboon & Anunmana 2024 [31] | Prospective | 22 NR | 18–66 | Molar | Zr L | 12 | 38.91 ± 7.09 | Zr 40.28 ± 9.1 L 39.11 ± 7.90 | This study found similar wear levels to enamel for both materials compared to natural teeth. |

| Woraganjanaboon et al., 2025 [32] | Prospective | 24 NR | ±37.13 | Molar | Zr L | 6, 12, 18 and 24 | Zr 6 months: 30.1 ± 3.4 12 months: 34.2 ± 3.0 18 months: 37.7 ± 4.0 24 months: 41.6 ± 4.5 L 6 months: 33.2 ± 6.0 12 months: 39.8 ± 5.8 18 months: 44.5 ± 6.6 24 months: 51.9 ± 7.7 | Zr 6 months: 29.8 ± 6.9 12 months: 34.8 ± 5.6 18 months: 40.6 ± 7.1 24 months: 45.2 ± 4.8 L 6 months: 37.0 ± 7.1 12 months: 43.3 ± 7.4 18 months: 48.5 ± 6.3 24 months: 53.6 ± 5.6 | Lithium disilicate and 5Y-TZP crowns did not affect enamel wear more than enamel against enamel. |

| Author and Year | Polishing Technique | Reported Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Stober et al., 2014 [26] | Sequential mechanical polishing with diamond abrasives, followed by glaze application. | Polishing reduces the abrasiveness of zirconia, decreasing wear on opposing teeth. |

| Mundhe et al., 2015 [25] | Glazing for metal-ceramic ceramics, mechanical polishing for zirconia crowns (polishing protocol not specified). | Glazing and polishing are important for reducing enamel wear. |

| Esquivel-Upshaw et al., 2020 [14] | Silicone mechanical polishers (Denerica; Dental Corp., Toronto, ON, Canada) with coarse-to-fine grit for crown polishing. Final polishing with diamond paste (DirectDia Paste Diamond Polishing Paste; Shofu Dental Corp., Kyoto, Japan) applied with stiff bristle brush. | Polishing with low roughness is essential to reduce antagonist enamel wear. |

| Nazirkar et al., 2020 [27] | Sequential mechanical polishing with diamond abrasives, followed by glaze application. | Proper polishing reduces roughness and antagonist enamel wear. |

| Tang et al., 2021 [30] | Polishing with ceramic polishers impregnated with diamond abrasives (Dura-Polish DIA; Shofu Dental Corp., Kyoto, Japan). | Polishing reduces roughness and abrasiveness, minimizing enamel wear. |

| Deval et al., 2021 [28] | Not specified in the study. | Adequate polishing is crucial to minimize antagonist enamel wear. |

| Selvaraj et al., 2021 [29] | Sequential polishing with rotary diamond instruments (coarse, medium, fine, and superfine) for 20 to 30 s each. | Sequential polishing reduces zirconia roughness, minimizing antagonist enamel wear. Surfaces with controlled roughness cause less abrasion to natural teeth. |

| Woraganjanaboon & Anunmana 2024 [31] | Sequential polishing with diamond points: coarse, medium, and fine (ZilMaster; Shofu Dental Corp., Kyoto, Japan). | Sequential polishing is important for achieving low roughness, minimizing enamel wear. |

| Woraganjanaboon et al., 2025 [32] | Sequential polishing with diamond points: coarse, medium, and fine (ZilMaster; Shofu Dental Corp., Kyoto, Japan). | Sequential polishing helps reduce the abrasive impact on opposing teeth. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rosa, C.D.D.R.D.; Bento, V.A.A.; Duarte, N.D.; Gomes, J.M.d.L.; Okamoto, R.; Buchaim, R.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; Issa, J.P.M.; Pellizzer, E.P. Comparative Wear of Opposing Natural Enamel by Different Ceramic Materials in Fixed Dental Protheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010037

Rosa CDDRD, Bento VAA, Duarte ND, Gomes JMdL, Okamoto R, Buchaim RL, Buchaim DV, Issa JPM, Pellizzer EP. Comparative Wear of Opposing Natural Enamel by Different Ceramic Materials in Fixed Dental Protheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa, Cleber Davi Del Rei Daltro, Victor Augusto Alves Bento, Nathália Dantas Duarte, Jéssica Marcela de Luna Gomes, Roberta Okamoto, Rogerio Leone Buchaim, Daniela Vieira Buchaim, João Paulo Mardegan Issa, and Eduardo Piza Pellizzer. 2026. "Comparative Wear of Opposing Natural Enamel by Different Ceramic Materials in Fixed Dental Protheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010037

APA StyleRosa, C. D. D. R. D., Bento, V. A. A., Duarte, N. D., Gomes, J. M. d. L., Okamoto, R., Buchaim, R. L., Buchaim, D. V., Issa, J. P. M., & Pellizzer, E. P. (2026). Comparative Wear of Opposing Natural Enamel by Different Ceramic Materials in Fixed Dental Protheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010037