Subgingival Plaque Removal Efficacy and Oral Soft Tissue Safety of the Wave Electric Toothbrush: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

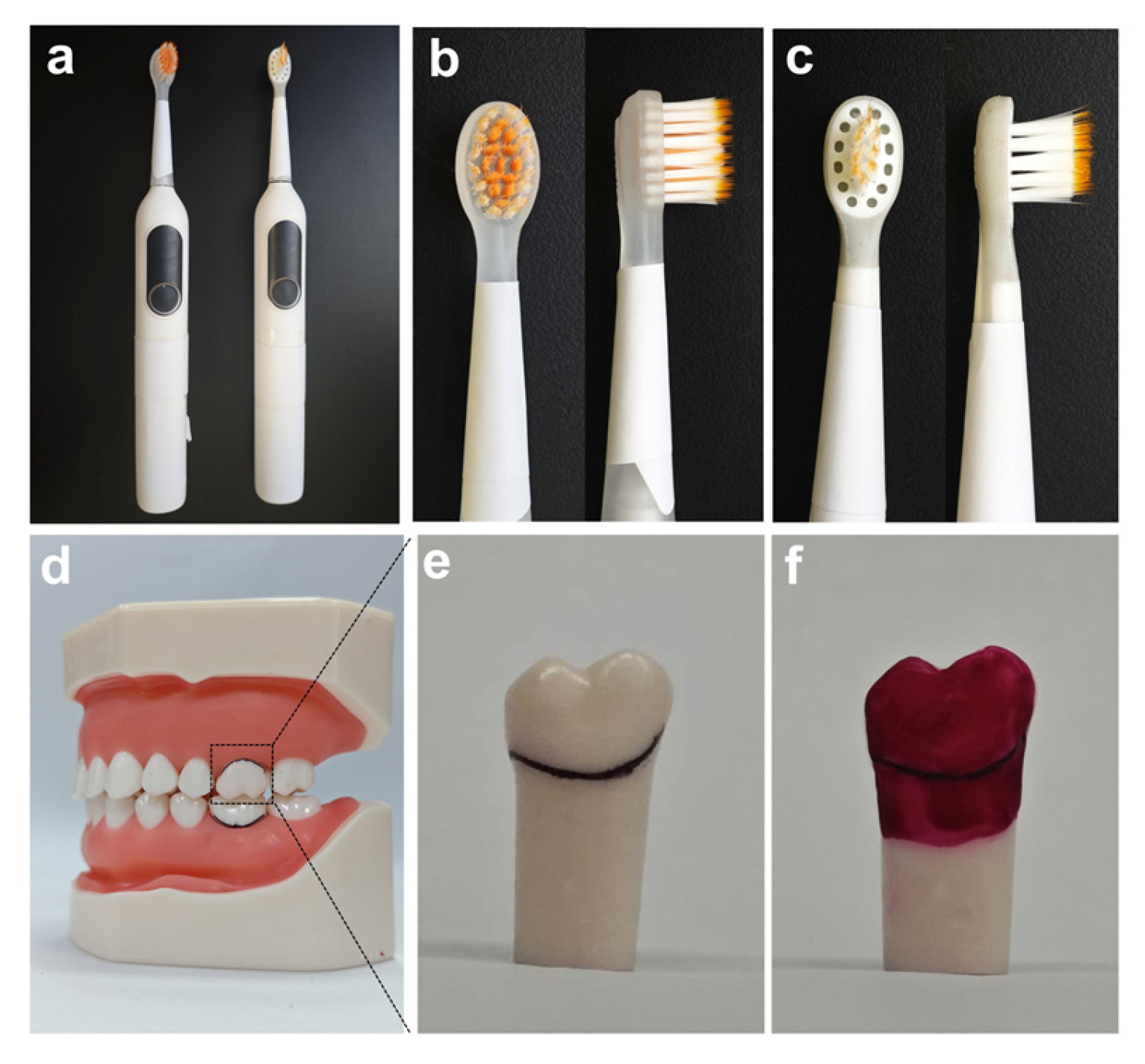

2.1. Utilization of Typodont Teeth and Animal Research Ethics

2.2. In Vitro Gingival Sulcus Cleaning Efficacy Experimental Design

2.3. Cleaning Performance Evaluation

2.4. In Vivo Safety Experiment Design Using Animal Models

2.5. Soft Tissue Safety Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

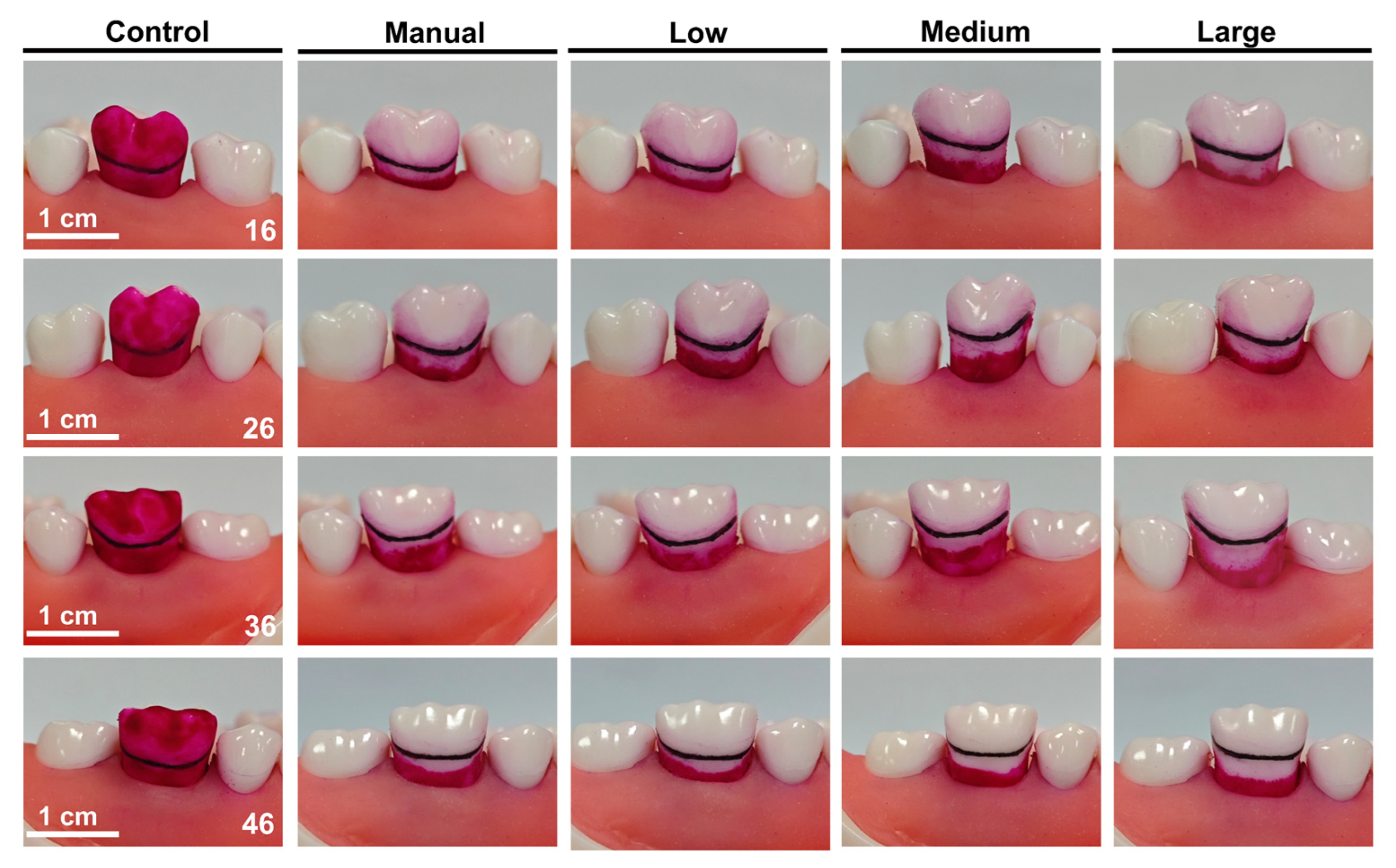

3.1. Cleaning Efficacy of Buccal Surface and Gingival Sulcus

3.2. Oral Bleeding Conditions

3.3. H&E Staining

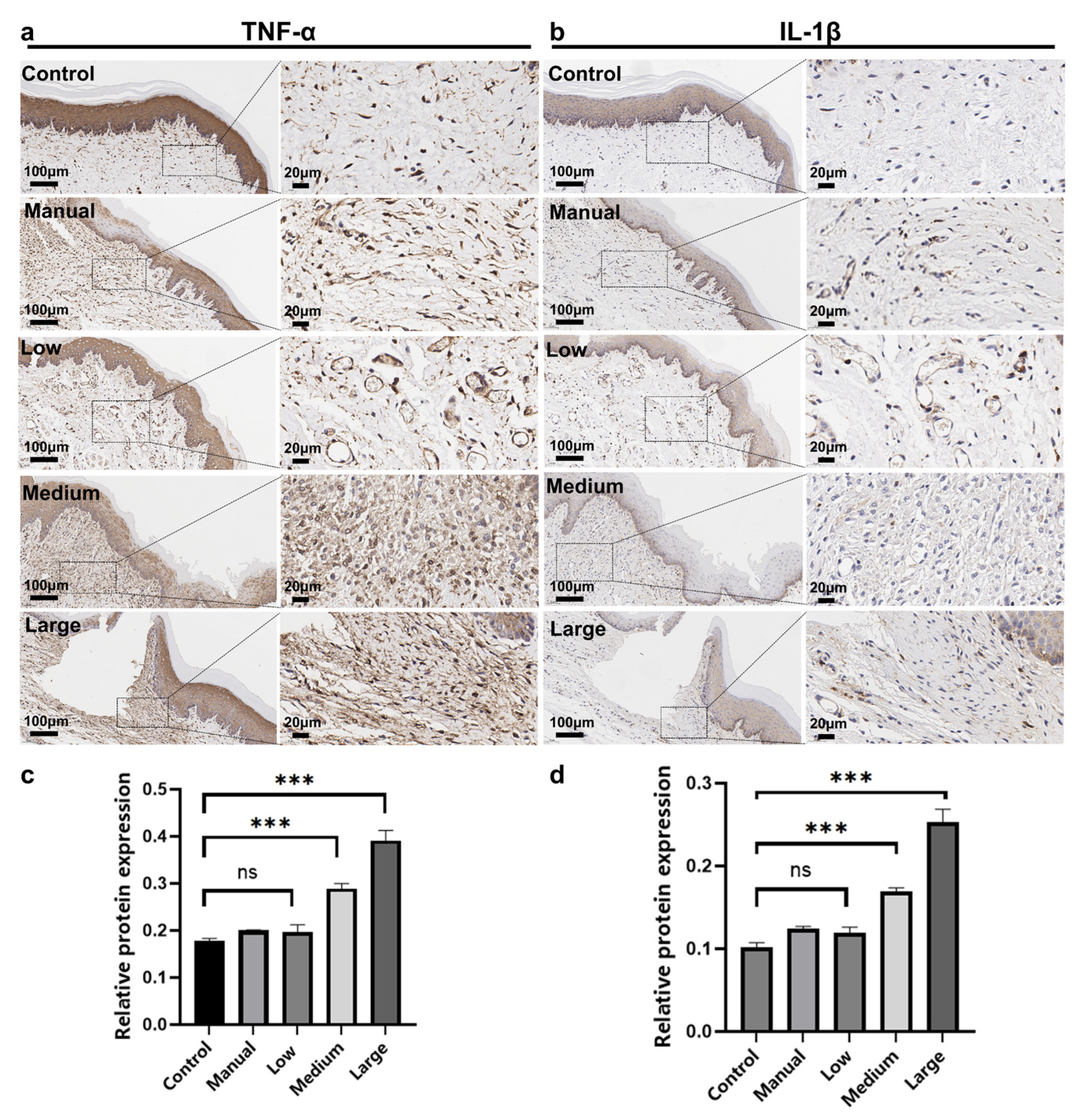

3.4. Immunohistochemical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jain, N.; Dutt, U.; Radenkov, I.; Jain, S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: Actions, discussion and implementation. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The oral microbiota: Dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.C.; Luo, B.W.; Lam, W.Y.; Baysan, A.; Chu, C.H.; Yu, O.Y. Updates on Caries Risk Assessment-A Literature Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Wen, J.; Cui, G.; Liang, J.; Pang, L.; Lin, H. Comparison of modified bass, rolling, and current toothbrushing techniques for the efficacy of plaque control—A randomized trial. J. Dent. 2023, 135, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.C. An effective method of personal oral hygiene. J. La. State Med. Soc. 1954, 106, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Erbe, C.; Jacobs, C.; Klukowska, M.; Timm, H.; Grender, J.; Wehrbein, H. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the plaque removal efficacy of an oscillating-rotating toothbrush versus a sonic toothbrush in orthodontic patients using digital imaging analysis of the anterior dentition. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gopalkrishna, P.; Syed, A.K.; Sathiyabalan, A. The Impact of Toothbrushing on Oral Health, Gingival Recession, and Tooth Wear-A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağdeviren, F.; Van der Weijden, G.A.F.; Zijlstra, C.P.L.; Slot, D.E. The Effectiveness of Power Versus Manual Toothbrushes on Plaque Removal and Gingival Health in Children-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2025, 23, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosema, N.A.; Adam, R.; Grender, J.M.; Van der Sluijs, E.; Supranoto, S.C.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Gingival abrasion and recession in manual and oscillating-rotating power brush users. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2014, 12, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.D.; Kanagasingam, S.; Cook, N.; Krysmann, M.; Taylor, K.; Pisani, F. The Effect of Different Electric Toothbrush Technologies on Interdental Plaque Removal: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitchika, V.; Pink, C.; Völzke, H.; Welk, A.; Kocher, T.; Holtfreter, B. Long-term impact of powered toothbrush on oral health: 11-year cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busscher, H.J.; Jager, D.; Finger, G.; Schaefer, N.; van der Mei, H.C. Energy transfer, volumetric expansion, and removal of oral biofilms by non-contact brushing. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyborg, J.; Renvert, S.; Anderberg, P.; Larsson, T.; Sanmartin-Berglund, J. Results of objective brushing data recorded from a powered toothbrush used by elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment related to values for oral health. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 28, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Makhmari, S.A.; Kaklamanos, E.G.; Athanasiou, A.E. Short-term and long-term effectiveness of powered toothbrushes in promoting periodontal health during orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 152, 753–766.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyborg, J.; Renvert, S.; Sanmartin Berglund, J.; Anderberg, P. Use of a powered toothbrush to improve oral health in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Gerodontology 2023, 40, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rominger, R.L.; Patcas, R.; Hamza, B.; Schätzle, M.; Wegehaupt, F.J.; Hersberger-Zurfluh, M.A. Cleaning performance of electric toothbrushes around brackets applying different brushing forces: An in-vitro study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preda, C.; Butera, A.; Pelle, S.; Pautasso, E.; Chiesa, A.; Esposito, F.; Oldoini, G.; Scribante, A.; Genovesi, A.M.; Cosola, S. The Efficacy of Powered Oscillating Heads vs. Powered Sonic Action Heads Toothbrushes to Maintain Periodontal and Peri-Implant Health: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.; Tsoi, J.K.H.; Lo, E.C.M.; Matinlinna, A.J.P. Safety and Design Aspects of Powered Toothbrush-A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.C.; Zaugg, C.; Weiger, R.; Walter, C. Brushing without brushing?—A review of the efficacy of powered toothbrushes in noncontact biofilm removal. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, P.K.; Prasad, K.V.V. Distribution of dental plaque and gingivitis within the dental arches. J. Int. Med. Res. 2017, 45, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, K.; Egelberg, J.; Hornbuckle, C.; Oliver, R.; Rathbun, E. Effect of tooth cleaning procedures on gingival sulcus depth. J. Periodontal Res. 1974, 9, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, I.L.; Van der Weijden, F.; Doerfer, C.; Herrera, D.; Shapira, L.; Polak, D.; Madianos, P.; Louropoulou, A.; Machtei, E.; Donos, N.; et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: Managing gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasance, F.A.; Gubler, A.; Attin, T.; Wegehaupt, F.J. Interplay Between the In-Vitro Cleaning Performance and Wear of Manual Toothbrushes in Fixed Orthodontic Appliances. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2024, 22, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi, T.; Takenaka, S.; Sakaue, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Nagata, R.; Hasegawa, T.; Ohshima, H.; Terao, Y.; Noiri, Y. Adjunct use of mouth rinses with a sonic toothbrush accelerates the detachment of a Streptococcus mutans biofilm: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.; Kreplak, L.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Labrie, D.; Shimokawa, C.A.K.; Price, R.B. Effect of tooth brushing on gloss retention and surface roughness of five bulk-fill resin composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Staufer, S.; Jennes, B.; Gaengler, P. Clinical validation of robot simulation of toothbrushing--comparative plaque removal efficacy. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axe, A.; Mueller, W.D.; Rafferty, H.; Lang, T.; Gaengler, P. Impact of manual toothbrush design on plaque removal efficacy. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, H.M.; Kim, Y.W. Comparative Analysis of Plaque Removal and Wear between Electric–Mechanical and Bioelectric Toothbrushes. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S. Effects of soil acidification on humus, electric charge, and bacterial community diversity. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obukavitha, D.; Geetha Priya, P.R.; Asokan, S.; Yogesh Kumar, T.D. Effectiveness of Plaque Removal Using Different Toothbrushes in Children—A Comparative Study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2024, 35, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, T.; Tian, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, H. A double-layer thin oral film for wet oral mucosa adhesion and efficient treatment of oral ulcers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, J.; Yu, J.-H.; Guan, S.; Xu, X.-M.; Mei, L. Role of autophagy in the periodontal ligament reconstruction during orthodontic tooth movement in rats. J. Dent. Sci. 2020, 15, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Qian, K.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, T.; Yang, X.; Mu, Y.; et al. Precise Modulation of Pericyte Dysfunction by a Multifunctional Nanoprodrug to Ameliorate Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 14348–14366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadakamadla, S.K.; Rathore, V.; Mitchell, A.E.; Johnson, N.; Morawska, A. Protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of an online parenting intervention for promoting oral health of 2–6 years old Australian children. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, M.E.; Perazzo, A.; Manganaro, J.; Tabani, Y.; Milleman, K.R.; Milleman, J.L.; Walsh, L.J. Clinical Assessment of Plaque Removal Using a Novel Dentifrice Containing Cellulose Microfibrils. Dent. J. 2023, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, A.R.; Pushalkar, S.; Gulivindala, D.; Butler, T.; Li, Y.; Annam, K.R.C.; Glodzik, L.; Ballman, K.V.; Corby, P.M.; Blennow, K.; et al. Periodontal dysbiosis associates with reduced CSF Aβ42 in cognitively normal elderly. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 13, e12172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsha, T.E.; Prince, Y.; Davids, S.; Chikte, U.; Erasmus, R.T.; Kengne, A.P.; Davison, G.M. Oral Microbiome Signatures in Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, J.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, M.; Chapple, I.L.; Hannig, M.; Marsh, P.D.; Meuric, V.; Pedersen, A.M.; Tonetti, M.S.; Wade, W.G.; Zaura, E. The oral microbiome—An update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, E.; Curtis, M.A.; Neves, J.F. The role of oral bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsma, M.A.; van de Lagemaat, M.; Busscher, H.J.; Geertsema-Doornbusch, G.I.; Atema-Smit, J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Ren, Y. Synergy of brushing mode and antibacterial use on in vivo biofilm formation. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubovics, N.S.; Goodman, S.D.; Mashburn-Warren, L.; Stafford, G.P.; Cieplik, F. The dental plaque biofilm matrix. Periodontology 2021, 86, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montevecchi, M.; Valeriani, L.; Bellanova, L.; Stefanini, M.; Zucchelli, G. In-vitro comparison of two different toothbrush bristles about peri-implant sulcus penetration. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 22, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, J.; Tomasi, C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S158–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürbüz, S.; Çankaya, Z.T.; Cinal, E.; Koçyiğit, E.G.; Bodur, A. Effects of interactive power toothbrush with or without application assistance on the plaque, gingivitis, and gingival abrasion among dental students: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5931–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzan, N.; Muniz, F.; Rösing, C.K. Are bristle stiffness and bristle end-shape related to adverse effects on soft tissues during toothbrushing? A systematic review. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosshardt, D.D.; Lang, N.P. The junctional epithelium: From health to disease. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, K.; Tanaka, H.; Fukuzawa, K.; Nakajima, J.; Ozaki, M.; Kato, N.; Kawato, T. Effects of Electric-Toothbrush Vibrations on the Expression of Collagen and Non-Collagen Proteins through the Focal Adhesion Kinase Signaling Pathway in Gingival Fibroblasts. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.A.; Davis, T.A. Key early proinflammatory signaling molecules encapsulated within circulating exosomes following traumatic injury. J. Inflamm. 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. The spectrum of inflammatory responses. Science 2021, 374, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Qian, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Gao, R.; Xiao, H.; Wang, J. MAPK and NF-κB Pathways Are Involved in Bisphenol A-Induced TNF-α and IL-6 Production in BV2 Microglial Cells. Inflammation 2015, 38, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bao, L.; Xuan, L.; Song, B.; Lin, L.; Han, H. Chebulagic acid inhibits the LPS-induced expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in endothelial cells by suppressing MAPK activation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Xue, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, M.; Zang, B. Hydroxysafflor yellow A attenuates the expression of inflammatory cytokines in acute soft tissue injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xue, L.F.; Xu, Y.X.; Yue, J.; Zhao, J.Z.; Xiao, W.L. Periodontal health and oral hygiene of children with orofacial clefts in Eastern China. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | TP | BSCR (%) | GSCR (%) | MGSCD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6) | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Manual (n = 6) | 16 | 100 | 44.1 ± 1.9 | 1.32 ± 0.14 |

| 26 | 100 | 28.7 ± 3.5 | 1.39 ± 0.07 | |

| 36 | 100 | 38.2 ± 7.7 | 1.62 ± 0.47 | |

| 46 | 100 | 42.6 ± 2.2 | 1.31 ± 0.36 | |

| Low (n = 6) | 16 | 100 | 43.4 ± 2 | 1.39 ± 0.23 |

| 26 | 100 | 28.6 ± 3.7 | 1.55 ± 0.31 | |

| 36 | 100 | 38.1 ± 1.1 | 1.85 ± 0.76 | |

| 46 | 100 | 35.7 ± 1.7 | 1.50 ± 0.29 | |

| Medium (n = 6) | 16 | 100 | 58.8 ± 6.7 | 1.87 ± 0.29 |

| 26 | 100 | 49.1 ± 1.3 | 2.00 ± 0.08 | |

| 36 | 100 | 52.4 ± 7.5 | 2.30 ± 0.10 | |

| 46 | 100 | 52.7 ± 5.3 | 2.02 ± 0.52 | |

| Large (n = 6) | 16 | 100 | 68 ± 15.1 | 2.60 ± 0.36 |

| 26 | 100 | 54.7 ± 0.4 | 2.76 ± 0.25 | |

| 36 | 100 | 62.5 ± 11.5 | 2.28 ± 0.22 | |

| 46 | 100 | 55.7 ± 9.7 | 2.13 ± 0.13 |

| Group | Control | Manual | Low | Medium | Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding Frequency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 2.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, S.; Du, W.; Wu, J.; Lu, Y.; Ku, W.; Zhang, X.; Yu, D. Subgingival Plaque Removal Efficacy and Oral Soft Tissue Safety of the Wave Electric Toothbrush: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010029

Huang S, Du W, Wu J, Lu Y, Ku W, Zhang X, Yu D. Subgingival Plaque Removal Efficacy and Oral Soft Tissue Safety of the Wave Electric Toothbrush: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Siyuan, Weidong Du, Jie Wu, Yunyang Lu, Weili Ku, Xiliu Zhang, and Dongsheng Yu. 2026. "Subgingival Plaque Removal Efficacy and Oral Soft Tissue Safety of the Wave Electric Toothbrush: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010029

APA StyleHuang, S., Du, W., Wu, J., Lu, Y., Ku, W., Zhang, X., & Yu, D. (2026). Subgingival Plaque Removal Efficacy and Oral Soft Tissue Safety of the Wave Electric Toothbrush: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010029