Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale in German

Abstract

1. Introduction

Dental Neglect Scale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Process of Translating and Adapting the Scale into Questionnaire

2.2. Ethical Consideration

2.3. Design and Data Collection

2.4. Measures

2.5. Sociodemographic Variables

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Hypotheses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

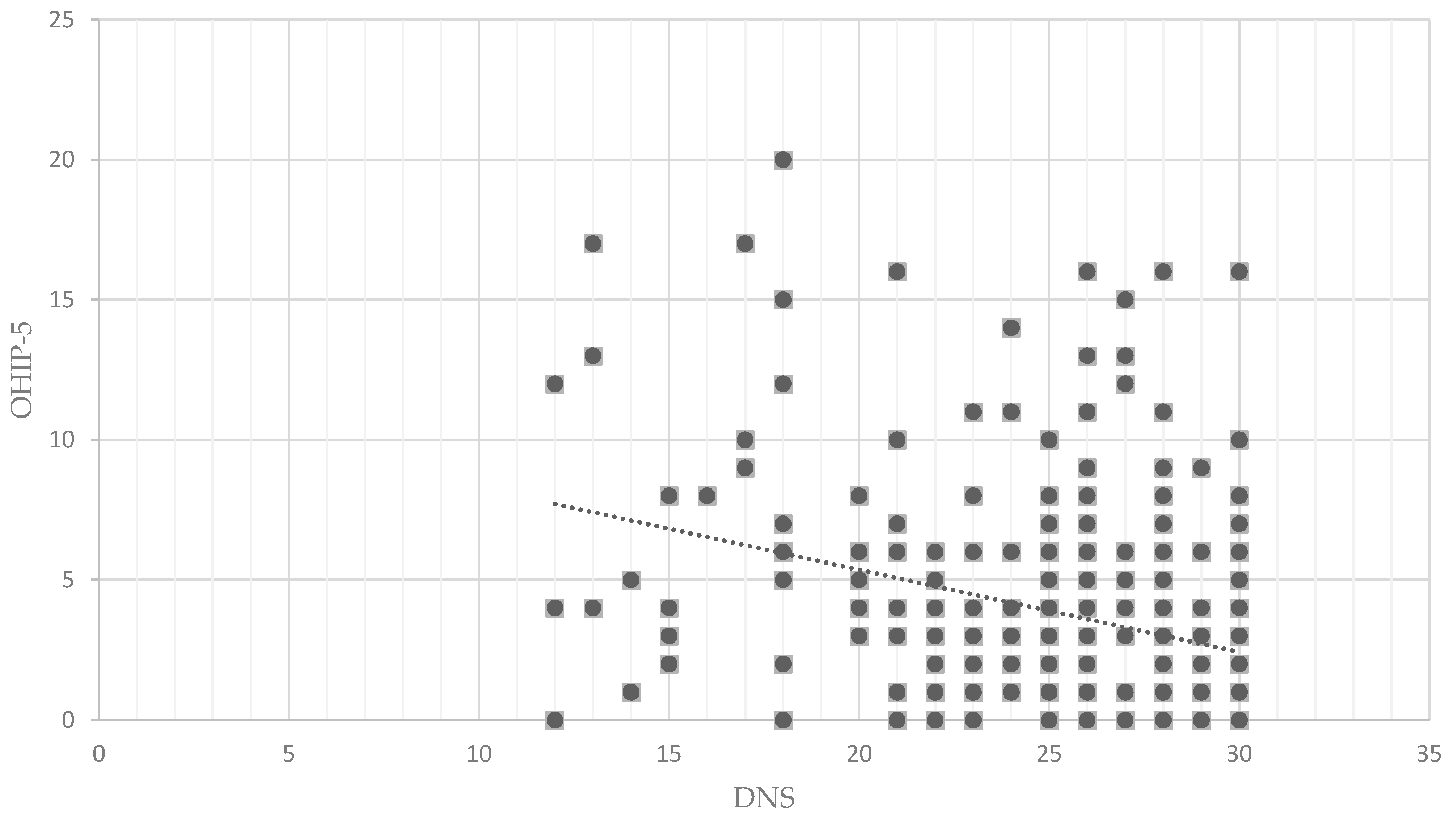

3.5. Convergent Validity

3.6. Differences Between Gender, Education and Age Groups

3.7. DNS and Preventive Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomson, W.M.; Spencer, A.J.; Gaudhwin, A. Testing a child dental neglect scale in South Australia. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1996, 24, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiller, L.; Lukefahr, J.; Kollogg, N. Dental Neglect. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 13, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, C.B.; Saintrain, M.V.; Vieira, A.P. Child, neglect and oral health. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, W.M.; Locker, D. Dental neglect and dental health among 26-year-olds in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2000, 28, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Thomson, W.M. The Dental Neglect Indifference scales compared. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2002, 30, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgiu, B.A.; Sfeatcu, R.; Mihai, C.; Ilici, R.R.; Parlatescu, I.; Tribus, L. Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale among Romanian Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaret, E.; Astrøm, A.N.; Haugejorden, O.; Klock, K.S.; Trovik, T.A. Assessment of the reliability and validity of the Dental Neglect Scale in Norwegian adults. Community Dent. Health. 2007, 24, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge, T.; Heima, M.; Johnson, E.K.; Weinstein, P. The Dental Neglect Scale in adolescents. BMC Oral Health 2009, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil Lingaraj, A.; Peter Simon, S.; Jithesh, J.; Hemant, B. Dental neglect among college going adolescents in Virajpet, India. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2014, 12, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, D.; Shanmugaavel, A.K. Dental neglect among children in Chennai. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2016, 34, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Chauhan, P.; Galhotra, V.; Duhan, H.; Kaur, M.; Sharma, S. Knowledge and Experience about Medical Emergencies among Dental Interns in Bangalore City. Int. Healthc. Res. J. 2019, 2, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.C.; Moysés, S.T.; Rocha, J.S.; Baldani, M.H.; Werneck, R.I.; Moysés, S.J. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Dental Neglect Scale for five-year-old children in Brazil. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athira, S.; Vallabhan, C.G.; Sivarajan, S.; Dithi, C.; Swathy Anand, P.J.; Chandran, T. Association of Dental Neglect Scale and Severity of Dental Caries among Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. S1), S812–S816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Dasar, P.; Nagarajappa, S.; Mishra, P.; Kumar, S.; Balsaraf, S.; Lalani, A.; Chauhan, A. Impact of Dental Neglect Scale on Oral Health Status Among Different Professionals in Indore City-A Cross- Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZC67–ZC70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, C.; Sham, A.S.; Ho, D.K.; Wong, J.H. The impact of dental neglect on oral health: A population based study in Hong Kong. Int. Dent. J. 2007, 57, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, N.M. Initial development of a scale to measure dental indifference. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1996, 24, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, S.K.; Humagain, M.; Upadhyaya, C.; Prajapati, D.; Srii, R. The impact of Dental Neglect on oral health among 16-30-year-olds in Dhulikhel, Kavrepalanchok, Nepal. J. Nepal. Soc. Periodontol. Oral Implantol. 2021, 5, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Oral Health Surveys, Basic Methods, 5th ed.; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, S.; Pentapati, K.C.; Bhat, P.V. Dental neglect and adverse birth outcomes: A validation and observational study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 11, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D.; Spencer, A.J. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Health. 1994, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- John, M.T.; Patrick, D.L.; Slade, G.D. The German version of the Oral Health Impact Profile--translation and psychometric properties. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2002, 110, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.T.; Miglioretti, D.L.; LeResche, L.; Koepsell, T.D.; Hujoel, P.; Micheelis, W. German short forms of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2006, 34, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A.; László, Z.; Kemper, C.J.; Rammstedt, B. Kurzskala zur Erfassung der Allgemeinen Lebenszufriedenheit (L-1). Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). Available online: https://zis.gesis.org/skala/Beierlein-Kovaleva-L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3-Kemper-Rammstedt-Kurzskala-zur-Erfassung-der-Allgemeinen-Lebenszufriedenheit-%28L-1%29?lang=de (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Franke, G.H.; Jaeger, S.; Glaesmer, H.; Barkmann, C.; Petrowski, K.; Braehler, E. Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corah, N.L. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J. Dent. Res. 1969, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corah, N.L.; Gale, E.N.; Illig, S.J. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978, 97, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnies, S.; Mehrstedt, M.; Eisentraut, I. Die Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) und das Dental Fear Survey (DFS)–Zwei Messinstrumente zur Erfassung von Zahnbehandlungsängsten. Z. Med. Psychol. 2002, 11, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinke, A.; Hannig, C.; Berth, H. Psychological distress and anxiety compared amongst dental patients- results of a cross-sectional study in 1549 adults. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmas, M. Has dental caries prevalence some connection with caries index values in adults? Caries Res. 2010, 44, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyle, J.; Jepsen, S. Der parodontale Screening-Index (PSI). Parodontologie 2000, 11, 17–21. Available online: https://www.quintessence-publishing.com/gbr/de/article/834835/parodontologie/2000/01/der-parodontale-screening-index-psi (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- DG Paro. Available online: https://par-richtlinie.de/psi/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- DG Paro. Available online: https://dgparo.de/forschung-praxis/parodontale-risikobeurteilung-psi/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA UR. Available online: https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Ogawa, H.; Lai, E.H. Improving oral health of older adults for healthy ageing. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Katheri, N.B.A.; Azzani, M. Oral health-related quality of life and its association with sense of coherence and social support among Yemeni immigrants in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krankenkassen Zentrale. Available online: https://www.krankenkassenzentrale.de/magazin/rekordhoch-178-millionen-deutsche-haben-eine-zahnzusatzversicherung (accessed on 6 May 2025).

| Dental Neglect Item (German Translation) | M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | α If ItemDeleted | Corrected Item-Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I keep up my home dental care. (Ich achte auf meine häusliche Zahnpflege.) | 4.50 | 0.82 | −1.740 | 2.724 | 0.613 | r = 0.684 |

| 2. I receive the dental care I should. (Ich erhalte die zahnärztliche Versorgung, die ich benötige.) | 4.62 | 0.87 | −2.706 | 7.174 | 0.696 | r = 0.350 |

| 3. I need dental care, but I put it off. (reversed) (Ich benötige eine zahnärztliche Behandlung, aber schiebe sie auf.) (umgepolt) | 3.97 | 1.42 | −1.048 | −0.381 | 0.708 | r = 0.383 |

| 4. I brush as well as I should. (Ich putze meine Zähne so gut, wie ich es sollte.) | 4.25 | 0.97 | −1.320 | 1.423 | 0.634 | r = 0.571 |

| 5. I control snacking between meals as well as I should. (Ich kontrolliere das Naschen zwischen den Mahlzeiten so gut, wie ich kann.) | 3.55 | 1.34 | −0.491 | −0.877 | 0.715 | r = 0.349 |

| 6. I consider my dental health to be important. (Ich halte meine Zahngesundheit für wichtig.) | 4.71 | 0.68 | −2.68 | 7.721 | 0.659 | r = 0.549 |

| Item | Factor 1 |

|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.873 |

| Item 2 | 0.502 |

| Item 3 | 0.621 |

| Item 4 | 0.745 |

| Item 5 | 0.486 |

| Item 6 | 0.772 |

| Explained Variance % | 46.44 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [CI] | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default | 14.452 | 9 | 0.107 | 1.606 | 0.975 | 0.959 | 0.064 [0.00–0.122] | 0.045 |

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DNS | - | |||||

| 2. BSI-18 | r = −0.283 p < 0.001 ** | - | ||||

| 3. OHIP-5 | r = −0.299 p < 0.001 ** | r = 0.234 p < 0.001 ** | - | |||

| 4. DMF_T | r = 0.132 p = 0.024 * | r = −0.030 p = 0.606 | r = 0.123 p = 0.034 * | - | ||

| 5. DMF_S | r = 0.137 p = 0.020 * | r = −0.054 p = 0.358 | r = 0.110 p = 0.059 | r = 0.968 p < 0.001 ** | - | |

| 6. PSI | r = 0.066 p = 0.290 | r = −0.070 p = 0.262 | r = −0.33 p = 0.592 | r = 0.346 p < 0.001 ** | r = 0.351 p < 0.001 ** | - |

| 7. DAS | r = −0.278 p < 0.001 ** | r = 0.335 p < 0.001 ** | r = 0.342 p < 0.001 ** | r = 0.046 p = 0.435 | r = 0.002 p = 0.971 | r = −0.001 p = 0.994 |

| Total Group | Low DNS Score (≤27) | High DNS Score (>27) | Test Statistics | p-Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 158 (52.8%) | N = 147 (48.2%) | |||||

| Gender N = 304 | ||||||

| Male | 129 (42.43%) | 72 (48.6%) | 57 (51.4%) | Chi-Quadrat = 2.494 | p = 0.287 | |

| Female | 175 (57.57%) | 85 (55.8%) | 90 (44.2%) | |||

| Age N = 305 | ||||||

| Young (until 49) | 137 (44.9%) | 98 (71.5%) | 39 (28.5%) | Chi-Quadrat = 38.77 | p < 0.001 ** | Phi = 0.357 |

| Old (50+) | 168 (55.1%) | 60 (35.7%) | 108 (64.3%) | |||

| Education N = 305 | ||||||

| A-Levels | 106 (34.75%) | 58 (54.7%) | 48 (45.3%) | Chi-Quadrat = 0.552 | p = 0.457 | |

| No A-Levels | 199 (65.25%) | 100 (50.3%) | 99 (49.7%) | |||

| Oral Health | ||||||

| PSI | N = 258 | N = 137 | N = 121 | T = −2.325 df = 256 | p = 0.021 * | Cohen’s d = −0.290 |

| M = 11.79 (SD = 5.35) | 11.07 (53.27) | 12.61 (5.34) | ||||

| DMF_T | N = 293 | 152 | 141 | T = −2.791 df = 290.851 | p = 0.006 * | Cohen’s d = −0.332 |

| M = 16.39 (SD = 8.32) | 15.1 (8.6) | 17.77 (7.8) | ||||

| DMF_S | N = 289 | 149 | 140 | T = −2.281 df = 287 | p = 0.005 * | Cohen’s d = −0.332 |

| M = 57.36 (SD = 34.67) | 51.58 (35.33) | 63.23 (33.08) | ||||

| DAS | N = 303 | 158 | 145 | T = 4.812 df = 249.770 | p < 0.001 ** | Cohen’s d = 0.548 |

| M = 10.34 (SD = 3.97) | 11.29 (4.23) | 9.19 (3.35) | ||||

| N (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low DNS Score (<=27) | High DNS Score (>27) | ||||

| How often do you brush your teeth each day? | |||||

| 1x | 36 (11.9%) | 12 (4.0%) | Χ2 = 14.112 df = 3 | p = 0.003 | Phi = 0.216 |

| 2x | 106 (35.0%) | 119 (39.3%) | |||

| 3x | 11 (3.6%) | 15 (5.0%) | |||

| 4x | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |||

| How often do you go to the dentist per year? | |||||

| Never | 12 (4.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | Χ2 = 15.046 df = 5 | p = 0.010 | Phi = 0.224 |

| 1x | 72 (24.0%) | 59 (19.7%) | |||

| 2x | 47 (15.7%) | 62 (20.7%) | |||

| 3x | 6 (2.0%) | 10 (3.3%) | |||

| 4x | 3 (1.0%) | 5 (1.7%) | |||

| More Often | 14 (4.7%) | 9 (3.0%) | |||

| How many times do you have tartar removed per year? | |||||

| Never | 36 (12.2%) | 12 (4.1%) | Χ2 = 16.480 df = 5 | p = 0.006 | Phi = 0.225 |

| 1x | 74 (25.1%) | 74 (25.1%) | |||

| 2x | 38 (12.9%) | 50 (16.9%) | |||

| 3x | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1.4%) | |||

| 4x | 2 (0.7%) | 3 (1.0%) | |||

| More Often | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |||

| How often do you have your teeth professionally cleaned per year? | |||||

| Never | 65 (22.0%) | 50 (16.9%) | Χ2 = 7.327 df = 4 | p = 0.120 | |

| 1x | 54 (18.2%) | 42 (14.2%) | |||

| 2x | 29 (9.8%) | 41 (13.9%) | |||

| 3x | 2 (0.7%) | 6 (2.0%) | |||

| 4x | 3 (1.0%) | 4 (1.4%) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weil, K.M.; Weßlau, T.M.; Magerfleisch, L.A.I.; Tröger, H.; Irmscher, L.; Bantel, D.; Meyer-Probst, C.T.; Petrowski, K.; Berth, H. Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale in German. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050225

Weil KM, Weßlau TM, Magerfleisch LAI, Tröger H, Irmscher L, Bantel D, Meyer-Probst CT, Petrowski K, Berth H. Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale in German. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(5):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050225

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeil, Katharina Marilena, Theresa Marie Weßlau, Laura Agnes Ingrid Magerfleisch, Hannah Tröger, Lisa Irmscher, David Bantel, Clara Theres Meyer-Probst, Katja Petrowski, and Hendrik Berth. 2025. "Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale in German" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 5: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050225

APA StyleWeil, K. M., Weßlau, T. M., Magerfleisch, L. A. I., Tröger, H., Irmscher, L., Bantel, D., Meyer-Probst, C. T., Petrowski, K., & Berth, H. (2025). Validity and Reliability of the Dental Neglect Scale in German. Dentistry Journal, 13(5), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050225