Evaluating the Implementation and Effectiveness of Competency-Based Education in Sudanese Dental Curricula: A Comparative Analysis of Curriculum Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.2. Aims of the Study

- Document and analyze the influence that the different types of curricula have on the development and achievement of key competencies in various domains of dental education, including, but not limited to, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, knowledge base, clinical information gathering, diagnosis and treatment planning, therapy, prevention and health promotion, and management of clinical practice.

- Examine the perceptions and experiences of faculty members, students, and dental professionals regarding the integration and achievement of competency-based education in different education models.

1.3. Research Questions

- What are the roles of the different types of dental curricula (i.e., discipline-based, hybrid, integrated, and community-based) in achieving competency-based education in Sudanese dental schools?

- In achieving program competency goals, what are each curriculum type’s strengths and weaknesses, and how does this affect students’ preparedness for clinical practice?

- 3.

- How do perceptions from students, faculty, and dental professionals differ regarding the effectiveness of competency-based education? How does this approach assist them while practicing as dentists?

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Quantitative Component

2.2.1. Sample Size Calculation

- University of Khartoum (Faculty of Dentistry): 80 participants

- Ribat University (Dental Institute): 70 participants

- Gezira University (College of Dentistry): 76 participants

- Al Neelain University (Faculty of Dentistry): 54 participants

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Students:Only current undergraduate dental students enrolled at the participating institutions were included. To ensure that participants had adequate exposure to the curriculum, students must have completed more than 50% of their dental study program—that is, they should be at least midway through their education.

- Faculty:Eligible participants included full-time faculty members who are directly involved in teaching or curriculum development within the dental programs. Faculty members must have at least one academic year of teaching experience at their institution.

- Professionals:Licensed dental practitioners actively engaged in clinical practice were included, provided they have a minimum of two years of professional experience post-graduation. These participants were also expected to be involved in continuing dental education or curriculum evaluation initiatives.

2.2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Qualitative Component

2.3.1. Sample Size and Data Collection

2.3.2. Interview Process

- Curriculum Design and Implementation: The participants’ views on the strengths and weaknesses of their institution’s curriculum in preparing them for clinical practice.

- Clinical Training and Practice: The adequacy of hands-on training and the integration of theoretical knowledge with clinical practice.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Communication: How effectively the curriculum fosters communication skills and interdisciplinary learning.

- Innovations in Dental Education: Comparisons between competency-based education and traditional teaching approaches, and the perceived impact on professional readiness.

2.3.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

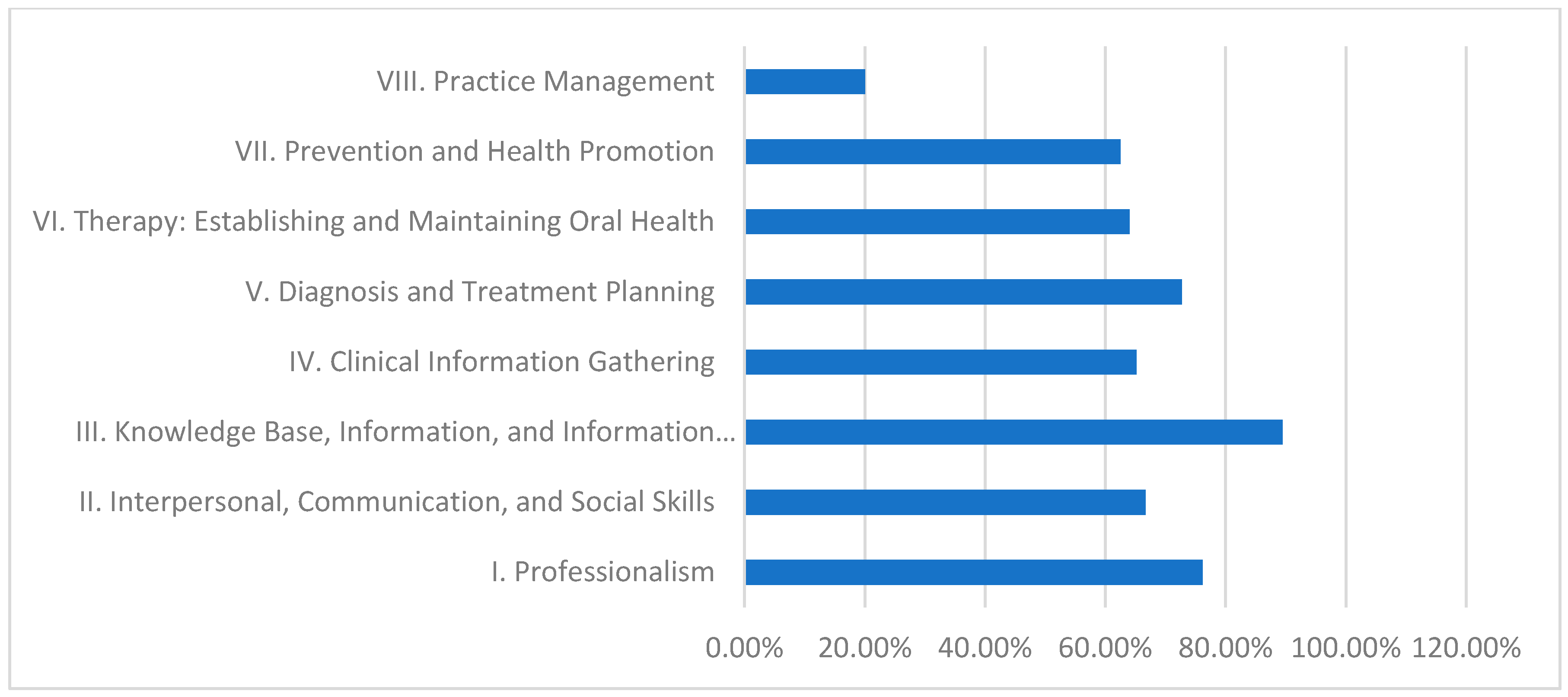

3.1.1. University of Khartoum—Discipline-Based Curriculum

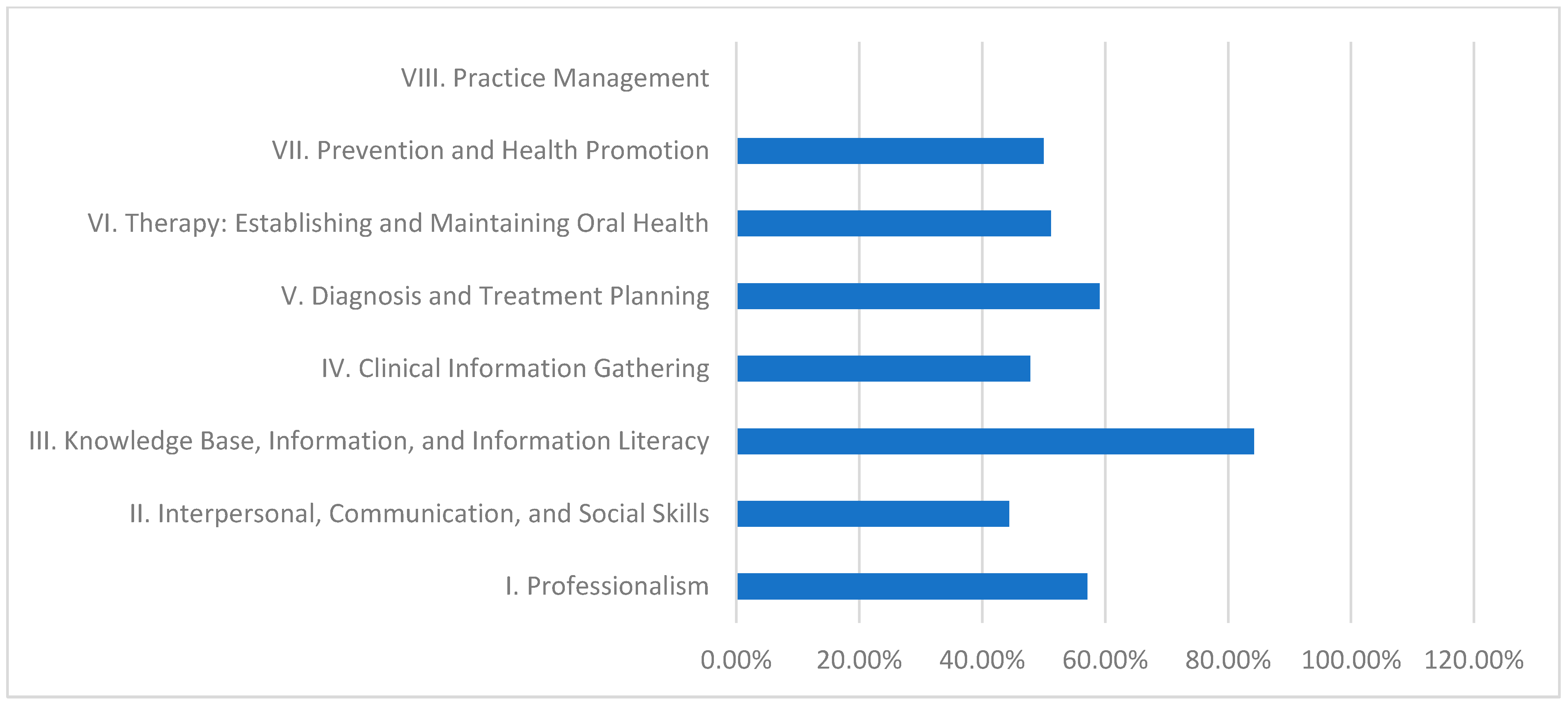

3.1.2. Al Neelain University—Hybrid Curriculum

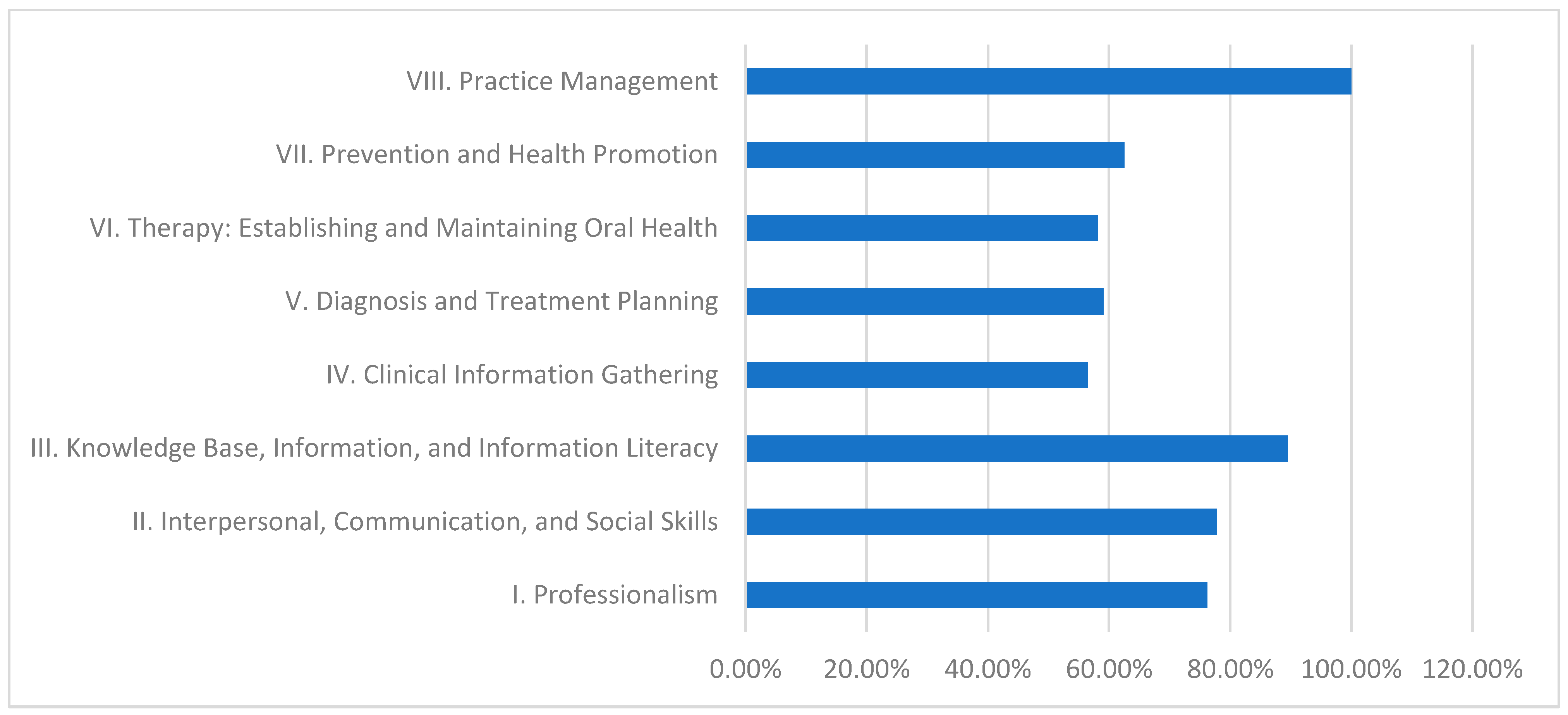

3.1.3. Ribat University—Integrated Curriculum

3.1.4. Gezira University—Community-Based Curriculum

3.1.5. Competency Fulfillment Across Dental Faculties

3.1.6. Conclusion of Quantitative Results

- Discipline-Based Curriculum (University of Khartoum):This model performs strongly in theoretical knowledge, as demonstrated by its high fulfillment in Domain III (89.5%).Strengths: High scores in Domain III indicate robust theoretical instruction.Weaknesses: Persistent deficiencies in practice management (20.0%) suggest a need for greater emphasis on administrative and practical skill development.

- Hybrid Curriculum (Al Neelain University):The hybrid curriculum achieves relatively good scores in theoretical areas (84.2% in Domain III) but struggles with practice management (0.0%) and some interpersonal skills.Strengths: Solid theoretical foundation evidenced by moderate to high Domain III performance.Weaknesses: Significant gaps in practice management and interpersonal communication undermine students’ overall clinical preparedness.

- Integrated Curriculum (Ribat University):The integrated model effectively balances theoretical and practical learning, achieving exceptional performance in practice management (100.0%) and high achievement in knowledge base (89.5%).Strengths: Outstanding practical competency in practice management, contributing to better overall clinical readiness.Weaknesses: Lower fulfillment in clinical information gathering (56.5%) indicates that even the balanced integrated approach may need enhanced strategies for effective real-time clinical data collection.

- Community-Based Curriculum (Gezira University):This curriculum excels in imparting theoretical knowledge and health promotion (84.2% in Domain III and 77.4% in Domain VII) yet is challenged by low performance in clinical information gathering (39.1%) and practice management (0.0%).Strengths: Strong knowledge base and emphasis on health promotion support public health objectives.Weaknesses: Inadequate practical training in clinical information gathering and practice management reflects challenges in applying theoretical knowledge in clinical and administrative contexts.

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Theme 1: Structured Educational Experiences

“The curriculum structure at Khartoum guarantees that we fully comprehend the theoretical component before going into hands-on application”.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Balance and Integration Challenges

“We often feel caught between traditional lectures and the newer competency requirements, which makes it hard to focus on one approach”.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Comprehensive Program Design

“The interdisciplinary courses at Ribat really help us understand how to manage diverse situations in dental practice”.

3.2.4. Theme 4: Community Engagement and Application

“Working within the community gives us real-world experience in health promotion, even if we lack some business management skills”.

3.2.5. Theme 5: Enhanced Preparedness and Confidence

“The competency-based training has made me feel more ready to tackle clinical challenges confidently”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discipline-Based Curriculum (University of Khartoum), Table 1 and Table 7 and Figure 2

4.2. Hybrid Curriculum (Al Neelain University), Table 2 and Table 4 and Figure 3

4.3. Integrated Curriculum (Ribat University), Table 3 and Table 7 and Figure 4

4.4. Community-Based Curriculum (Gezira University), Table 4 and Table 7 and Figure 5

4.5. Curriculum Structure Variations

4.6. Stakeholder Perceptions and Experiences Table 6

4.7. Recommendations

- Faculty Training:Implement mandatory annual competency-based workshops with certification and refresher courses to keep faculty updated on current teaching methodologies and assessment strategies.

- Curriculum Revision:Establish interdisciplinary committees (including educators, industry professionals, and administrators) to develop targeted action plans that integrate best practices.

- Policy Changes:Revise institutional guidelines to require regular curriculum evaluations, adopt innovative teaching methods (e.g., simulation-based learning), and set clear competency benchmarks with corresponding resource allocations.

- Feedback Mechanisms:Develop continuous feedback systems from students and alumni—such as annual surveys, focus groups, and performance audits—to inform ongoing improvements.

- Further Research:Investigate the long-term impact of competency-based education on clinical outcomes and professional readiness through longitudinal, experimental, and qualitative studies. This research should also explore factors behind competency gaps (e.g., the discrepancies observed between Ribat University and Al Neelain University) to provide data-driven insights for refining curricula and policies.

4.8. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Informed Consent Form for Participation in Research Study

- Abbas Gareeballa

- Yasir Hassan Elhassan

- Liena Babiker Mekki

- Emad Ali Albadawi

- Asim M Almughamsi

- Hadel Mahroos Alghabban

- Emad Rajih

- Walaa M Borhan

- Abdulfatah M. Alayoubi

- Muayad Albadrani

- The survey will take approximately 15–20 minutes to complete.

- Interviews will last about 45–60 minutes.

- Participation is entirely voluntary.

- You may withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

- You have the right not to answer any question that you are uncomfortable with.

References

- Nadershahi, N.; Bender, D.; Beck, L.; Lyon, C.; Blaseio, A. An overview of case–based and problem–based learning methodologies for dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 77, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, P.; McFarland, K.; Lange, B.; Ojha, D.; Chandak, A. Supervising dentists’ perspectives on the effectiveness of community-based dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badner, V.; Ahluwalia, K.; Murrman, M.; Sanogo, M.; Darlington, T.; Edelstein, B. A competency-based framework for training in advanced dental education: Experience in a community-based dental partnership program. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 74, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foláyan, M.; Khami, M.; Folaranmi, N.; Popoola, B.; Sofola, O.; Ligali, T.; Esan, A.O.; Orenuga, O. Determinants of preventive oral health behavior among senior dental students in Nigeria. BMC Oral Health 2013, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maart, R.; Razia, Z.; Frantz, J. Dental educators’ views and knowledge of competencies required within a competency framework. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2021, 76, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, R.; Akbar, F.; Abdullah, A.; Mareta, Y. Knowledge and self-perception about preventive dentistry among Indonesian dental students. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2018, 18, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiritoso, S.; Gross, E.; Bean, C.; Casamassimo, P.; Levings, K.; Lloyd, P. Campus-based, community-based, and philanthropic contributions to predoctoral pediatric dental clinical education: Two years of experience at one dental college. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 79, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Ara, I.; Talukder, H.; Chowdhury, D.; Hossin, I.; Raihan, M. Teachers and clinical students’ perception of the core competencies of different subjects of the undergraduate BDS curriculum. Bangladesh J. Med. Educ. 2017, 8, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basudan, T.; Alhazzani, H.; Alsubaie, K.; Albalawi, W.; Alafare, S.; Badghaish, F.; Alotaibi, H.; Algohani, L.; Almalki, M.; Althobaiti, M.; et al. Implementation of evidence-based dentistry in restorative dentistry. J. Healthc. Sci. 2022, 2, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, M.; Rodriguez, T.E.; Brallier, L.B. Student and faculty satisfaction with their dental curriculum in a dental college in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 6839717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Iqbal, I.; Habiba, U.; Khan, S.; Rafat, R.K.; Iqbal, M. Business management’s inclusion in the dental curriculum: The opinion of Abbasi Shaheed Hospital’s postgraduates and dental graduates. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 2024, 4, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenjitwongsa, S.; Poolthong, S.; Bullock, A.; Oliver, R.G. Developing common competencies for Southeast Asian general dental practitioners. J. Dent. Educ. 2017, 81, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloah, J.; Scarbecz, M.; Bland, P.S.; Hottel, T.L. A comprehensive clinical competency-based assessment in periodontics. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 21, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah-Franco, S.; Hasel, R.; Tahir, A.; Chui, B.; Ywom, J.; Young, B.; Singh, M.; Turchi, S.; Pape, G.; Henson, B. A preclinical hybrid curriculum and its impact on dental student learning outcomes. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 85, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Guzmán-Armstrong, S.; Schenkel, A.; Allen, K.; Featherstone, J.; Goolsby, S.; Kanjirath, P.; Kolker, J.; Martignon, S.; Pitts, N.; et al. Development of a core curriculum framework in cariology for U.S. dental schools. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 80, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koole, S.; Bruyn, H. Contemporary undergraduate implant dentistry education: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 18, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arheiam, A.; Bankia, I.; Ingafou, M. Perceived competency towards preventive dentistry among dental graduates: The need for curriculum change. Libyan J. Med. 2015, 10, 26666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honey, J.; Lynch, C.; Burke, F.; Gilmour, A. Ready for practice? a study of confidence levels of final year dental students at Cardiff University and University College Cork. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 15, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmanaseer, W. Dental students’ perception and self-perceived confidence level in key dental procedures for general practice and the impact of competency implementation on their confidence level, part I (prosthodontics and conservative dentistry). Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 2015331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H. Book review: Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research [book review]. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 12, 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatharani, M.; Hilmy, N. Analysis of health literacy index difference amongst generation in jagapura primary healthcare work area. J. Agromedicine Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Rashid, B.; Stella, F. The impact of nurse educators’ attitude on nursing students’ academic performance and ethical growth at the department of nursing, eastern technical university of sierra leone. Afr. J. Health Nurs. Midwifery 2024, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullanmaa, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Pietarinen, J.; Soini, T. Curriculum coherence as perceived by district-level stakeholders in large-scale national curriculum reform in Finland. Curric. J. 2019, 30, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahed, A.; Naidoo, S.; Deepak, S. A preliminary inquiry on the association between pre-admission assessments and academic performance of first-year dental technology students’ within a South African University of Technology. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2021, 76, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena-Rivas, Y.; Huanquilef-Arriagada, M.; Arellano-Villalón, M.; Nuñez-Contreras, J.; Fuentes-Fernández, R. A report of the interdisciplinary education approach within the Universidad de la Frontera dental curriculum. Int. J. Odontostomatol. 2021, 15, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Shin, S.; Shin, B.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.; Bae, S. Development of nutritional biochemistry learning goals and core competencies in the dental hygiene curriculum. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2022, 22, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, R.; Hilario, H. Input from practice: Reshaping dental education for integrated patient care. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 659030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colodette, R.; Gomes, A. Mapping bioethics teaching in Brazilian dental schools. Revista Bioética 2022, 30, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonova, S.; Jessani, A.; Girard, F.; Macdonald, M.; Souza, G.; Tam, L.; Schroth, R. The Canadian core cariology curriculum: Outcomes of a national symposium. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 84, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Green, J.; Starchuk, C.; Senior, A.; Compton, S.; Gaudet-Amigo, G.; Lai, H.; Linke, B.; Patterson, S. Dental faculty and student views of didactic and clinical assessment: A qualitative description study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.; Pagni, S.; Park, S.; Karimbux, N. Early clinical exposure in U.S. dental schools and correlation with earlier competencies evaluation. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 84, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.C.; Shaikh, S.J.; Jeong, D.C.; Wang, L.; Gillig, T.K.; Godoy, C.G.; Appleby, P.R.; Corsbie-Massay, C.L.; Marsella, S.; Christensen, J.L.; et al. Causal inference in generalizable environments: Systematic representative design. Psychol. Inq. 2019, 30, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Koizumi, H.; Imai, H.; Furuchi, M.; Takatsu, M.; Shimoe, S. Education and licensure of dental technicians. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 64, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jhang, K.; Wang, W.; Lin, G.; Yen, S.; Wu, H. Applying apriori algorithm to explore long-term care services usage status—Variables based on the combination of patients with dementia and their caregivers. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1022860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Chandra, A.; Tripathi, S.; Rastogi, P.; Khanna, R. Evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental academics and the future of dental education across India. J. Med. Educ. 2021, 20, e113186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.; Hayes, M.; Taylor, J.; Wallace, J. A scoping review of simulation-based dental education. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenjitwongsa, S.; Oliver, R.; Bullock, A. Competence, competency-based education, and undergraduate dental education: A discussion paper. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezinelli, L.M.; Eduardo F de Palacio D da Heller, D.; Ramos, D.V.; Cavalcante, D.D.; Vasques, M.T.; Cesar, P.F.; Monte, J.C.; Campos, A.H.; Corrêa, L. Special care in the dental curriculum: A transversal axis for integrating oral health with Systemic Health. Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 43, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, O.; Embo, M.; Valcke, M.; Haerens, L. When theory beats practice: The implementation of competency-based education at healthcare workplaces. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, J.; Donnelly, L.; Brondani, M. Exploring dental student participation in interdisciplinary care team conferences in long-term care. Gerodontology 2017, 34, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Fulfillment (%) |

|---|---|

| I. Professionalism | 76.2% |

| II. Interpersonal, Communication, and Social Skills | 66.7% |

| III. Knowledge Base, Information, and Information Literacy | 89.5% |

| IV. Clinical Information Gathering | 65.2% |

| V. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | 72.7% |

| VI. Therapy: Establishing and Maintaining Oral Health | 64.0% |

| VII. Prevention and Health Promotion | 62.5% |

| VIII. Practice Management | 20.0% |

| Domain | Fulfillment (%) |

|---|---|

| I. Professionalism | 57.1% |

| II. Interpersonal, Communication, and Social Skills | 44.4% |

| III. Knowledge Base, Information, and Information Literacy | 84.2% |

| IV. Clinical Information Gathering | 47.8% |

| V. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | 59.1% |

| VI. Therapy: Establishing and Maintaining Oral Health | 51.2% |

| VII. Prevention and Health Promotion | 50.0% |

| VIII. Practice Management | 0.0% |

| Domain | Fulfillment (%) |

|---|---|

| I. Professionalism | 76.2% |

| II. Interpersonal, Communication, and Social Skills | 77.8% |

| III. Knowledge Base, Information, and Information Literacy | 89.5% |

| IV. Clinical Information Gathering | 56.5% |

| V. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | 59.1% |

| VI. Therapy: Establishing and Maintaining Oral Health | 58.1% |

| VII. Prevention and Health Promotion | 62.5% |

| VIII. Practice Management | 100.0% |

| Domain | Fulfillment (%) |

|---|---|

| I. Professionalism | 61.9% |

| II. Interpersonal, Communication, and Social Skills | 55.6% |

| III. Knowledge Base, Information, and Information Literacy | 84.2% |

| IV. Clinical Information Gathering | 39.1% |

| V. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | 50.0% |

| VI. Therapy: Establishing and Maintaining Oral Health | 50.0% |

| VII. Prevention and Health Promotion | 77.4% |

| VIII. Practice Management | 0.0% |

| Dental College | Competency Fulfilled | Competency Not Fulfilled | Not Clear | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Khartoum | 131 (67.9%) | 58 (30.1%) | 4 (2.1%) | 193 |

| Al Neelain University | 104 (53.9%) | 86 (44.6%) | 3 (1.6%) | 193 |

| Ribat University | 126 (65.3%) | 67 (34.7%) | 0 (0%) | 193 |

| Gezira University | 103 (53.4%) | 89 (46.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 193 |

| University | Stakeholder Group | Positive Perception (%) | Challenges Noted |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Khartoum | Students | 85% | Lack of Practice Management |

| Faculty | 80% | Administrative Skills Training Needed | |

| Professionals | 78% | Balanced Skill Development | |

| Al Neelain University | Students | 70% | Integration Challenges |

| Faculty | 65% | Conflicting Educational Approaches | |

| Professionals | 68% | Standardizing Outcomes | |

| Ribat University | Students | 90% | None |

| Faculty | 88% | Expansion of Integrative Strategies | |

| Professionals | 85% | None | |

| Gezira University | Students | 75% | Management Skill Gaps |

| Faculty | 70% | Balancing Community Engagement | |

| Professionals | 72% | Strengthening Management Skills |

| Theme | Description | CBE Framework Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Educational Experiences | Emphasizes a systematic curriculum that builds strong theoretical foundations to support effective clinical practice. | Oral Health Maintenance: Preventive care and disease management. Professionalism: Ethical conduct and accountability. Critical Thinking: Systematic analysis and decision making. |

| Balance and Integration Challenges | Highlights the difficulty in merging traditional lectures with modern CBE approaches, demanding a balance between theory and practice. | Communication: Clear and effective information exchange. Practice Management: Adaptability to curricular changes. Critical Thinking: Integrating diverse methods. |

| Comprehensive Program Design | Stresses an interdisciplinary curriculum that seamlessly integrates theory and practice to prepare students for complex clinical scenarios. | Oral Health Maintenance: Ensuring high-quality patient care. Health Promotion: Support of public health initiatives. Professionalism and Critical Thinking: Holistic problem solving. |

| Community Engagement and Application | Underscores the value of community-based experiences that transform theoretical knowledge into practical public health practice. | Health Promotion: Planning and implementing community initiatives. Oral Health Maintenance: Applying preventive care in real-world settings. Practice Management: Operational skills. |

| Enhanced Preparedness and Confidence | Indicates that competency-based education significantly boosts student readiness and self-confidence for facing clinical challenges. | Professionalism: Commitment to lifelong learning and ethics. Critical Thinking: Effective problem solving in dynamic environments. Communication: Confident patient interaction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gareeballa, A.; Elhassan, Y.H.; Mekki, L.B.; Albadawi, E.A.; Almughamsi, A.M.; Alghabban, H.M.; Rajih, E.; Borhan, W.M.; Alayoubi, A.M.; Tobaiqi, M.A.; et al. Evaluating the Implementation and Effectiveness of Competency-Based Education in Sudanese Dental Curricula: A Comparative Analysis of Curriculum Models. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13040139

Gareeballa A, Elhassan YH, Mekki LB, Albadawi EA, Almughamsi AM, Alghabban HM, Rajih E, Borhan WM, Alayoubi AM, Tobaiqi MA, et al. Evaluating the Implementation and Effectiveness of Competency-Based Education in Sudanese Dental Curricula: A Comparative Analysis of Curriculum Models. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(4):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13040139

Chicago/Turabian StyleGareeballa, Abbas, Yasir Hassan Elhassan, Liena Babiker Mekki, Emad Ali Albadawi, Asim M. Almughamsi, Hadel Mahroos Alghabban, Emad Rajih, Walaa M. Borhan, Abdulfatah M. Alayoubi, Muhammad Abubaker Tobaiqi, and et al. 2025. "Evaluating the Implementation and Effectiveness of Competency-Based Education in Sudanese Dental Curricula: A Comparative Analysis of Curriculum Models" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 4: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13040139

APA StyleGareeballa, A., Elhassan, Y. H., Mekki, L. B., Albadawi, E. A., Almughamsi, A. M., Alghabban, H. M., Rajih, E., Borhan, W. M., Alayoubi, A. M., Tobaiqi, M. A., & Albadrani, M. (2025). Evaluating the Implementation and Effectiveness of Competency-Based Education in Sudanese Dental Curricula: A Comparative Analysis of Curriculum Models. Dentistry Journal, 13(4), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13040139