In-Depth Multi-Approach Analysis of WGS Metagenomics Data Reveals Signatures Potentially Explaining Features in Periodontitis Stage Severity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

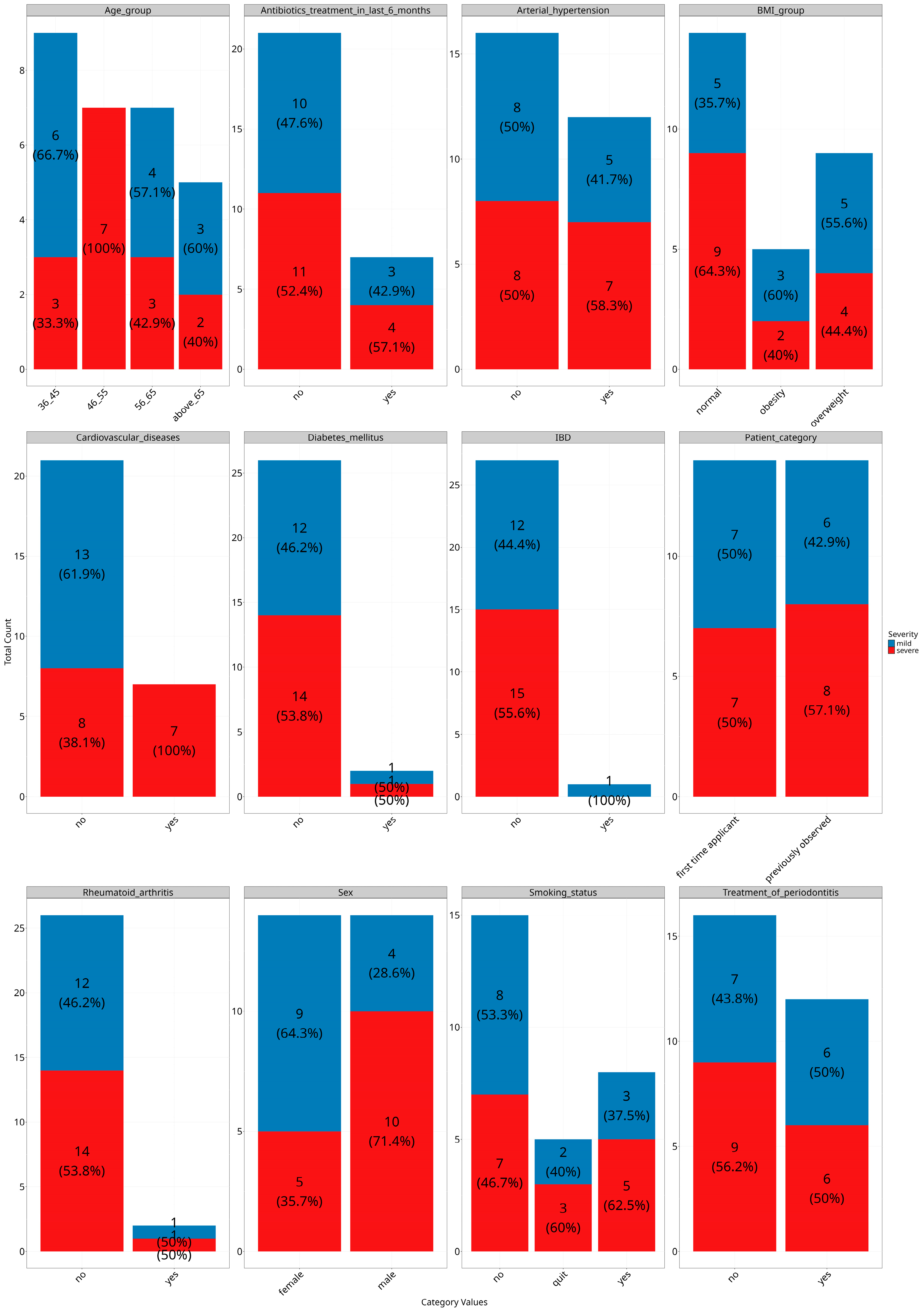

2.1. Study Cohort

- Men and women aged 18 years and older with a confirmed diagnosis of “Chronic periodontitis (K05.3) newly diagnosed or previously treated in the acute stage” with confirmed P. gingivalis presence by PCR of oropharyngeal swab;

- Mild and severe dynamics of the course of periodontitis according to CT scan;

- Signed voluntary informed consent for participation in the study.

- 4.

- Antibiotics treatment in the last month prior to visiting a dentist;

- 5.

- Performing hygienic cleaning of teeth prior to visiting a dentist;

- 6.

- Absence of P. gingivalis DNA in the biomaterial according to the results of PCR testing.

2.2. Samples and Data Collection

2.3. WGS Sequencing

2.4. WGS Data Processing

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

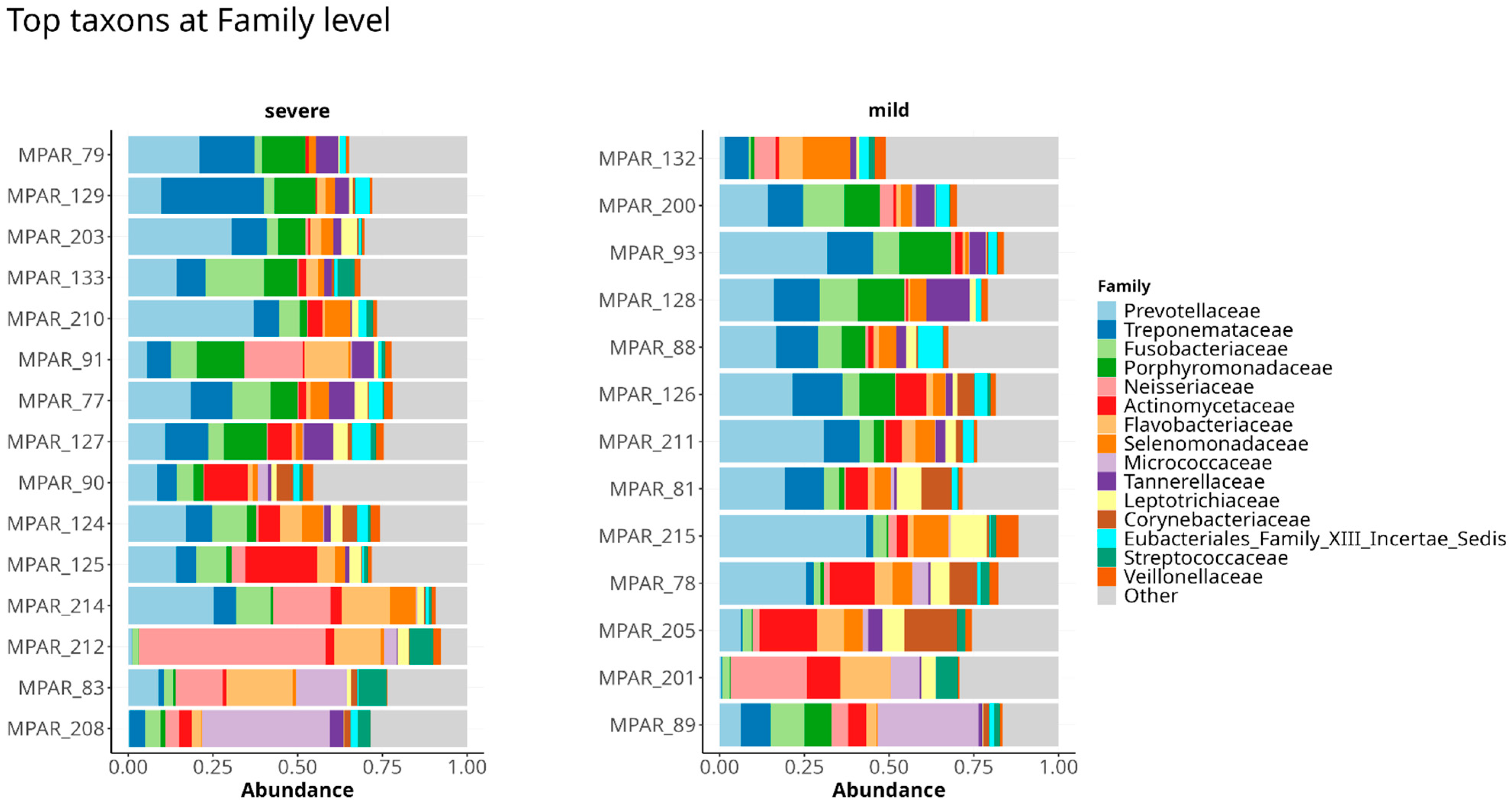

3.1. Taxonomy of Periodontal Microbiome of Periodontitis Patients Infected with P. gingivalis

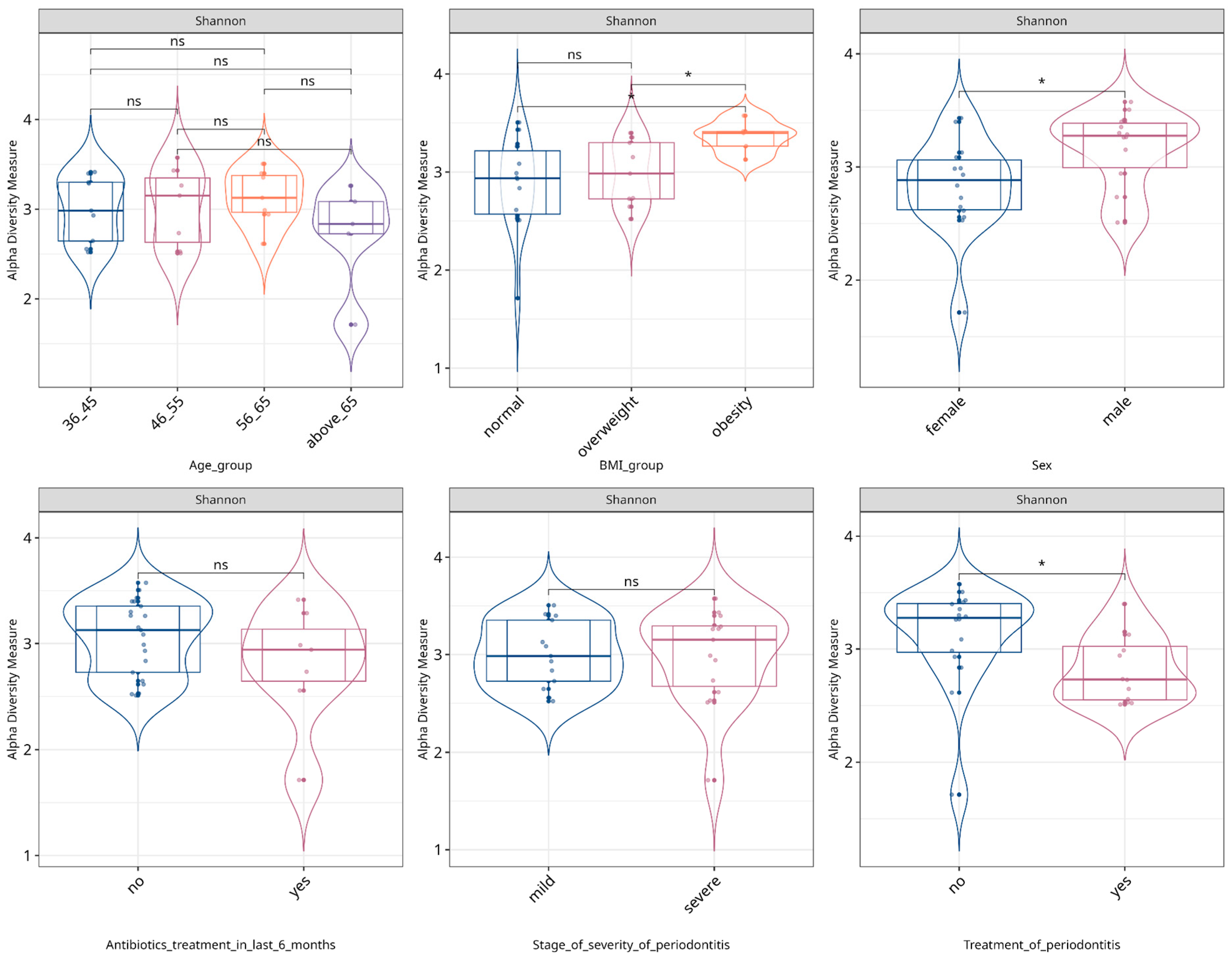

3.2. Alpha- and Beta-Diversity of WGS Metagenomics Data

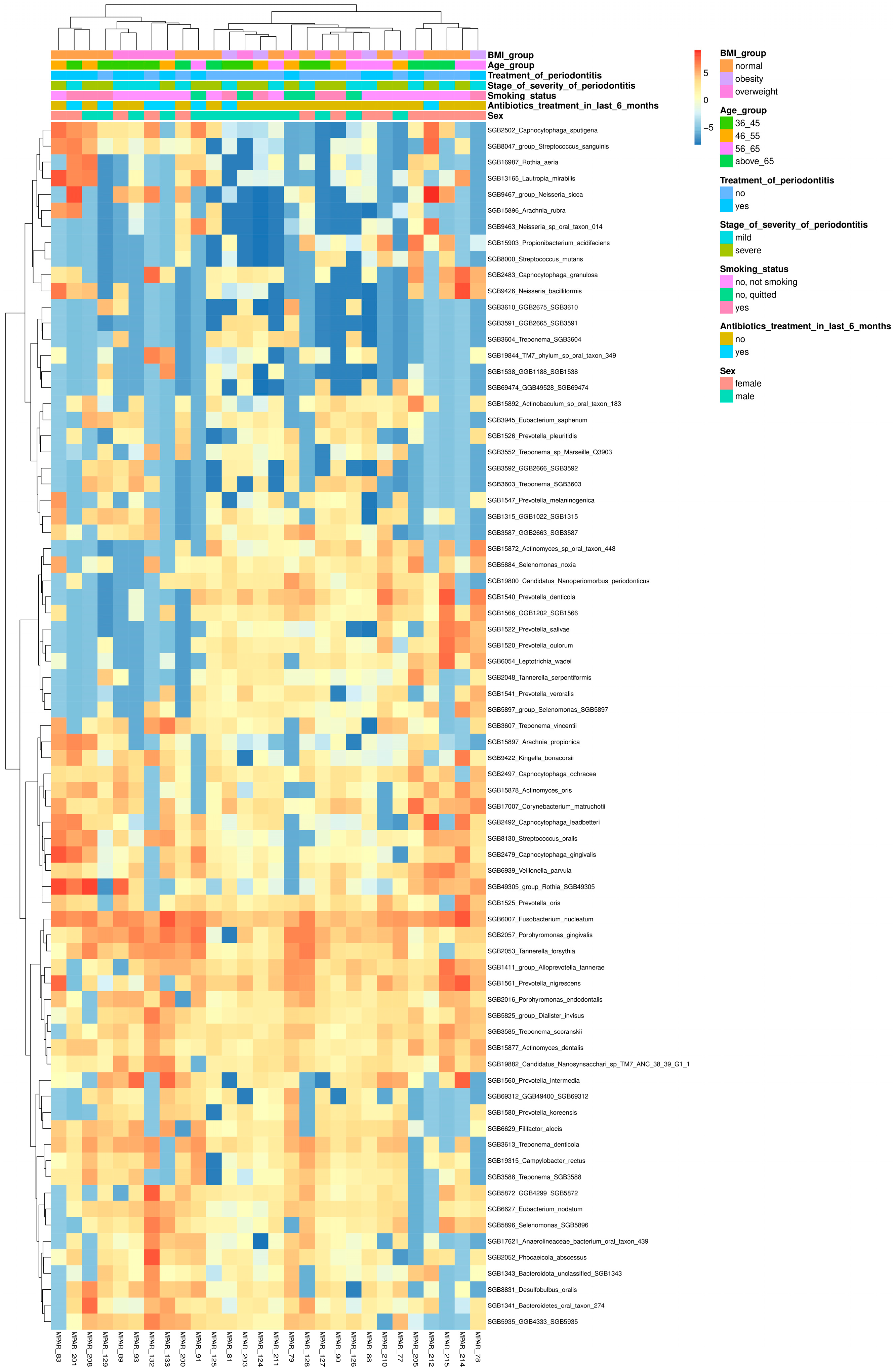

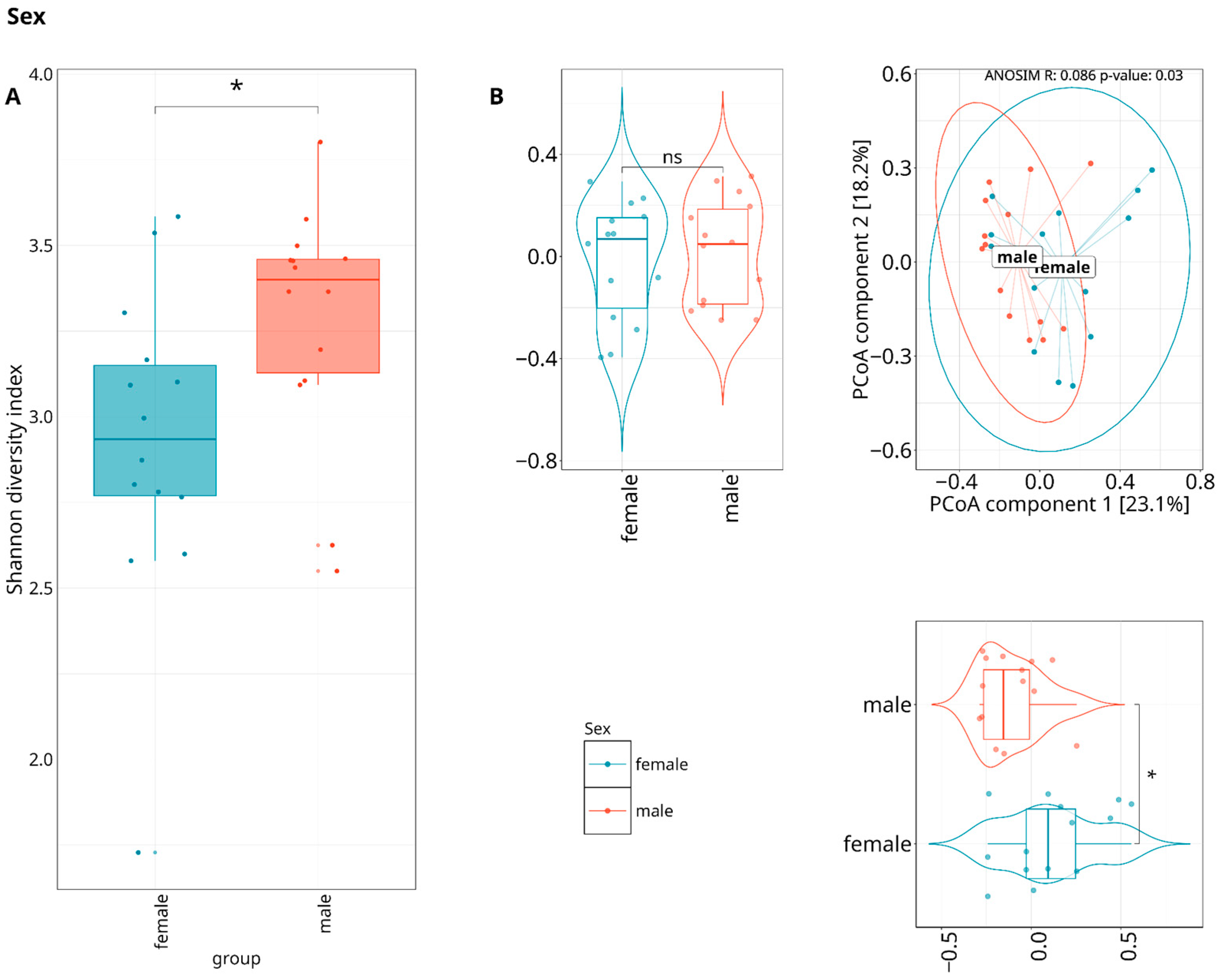

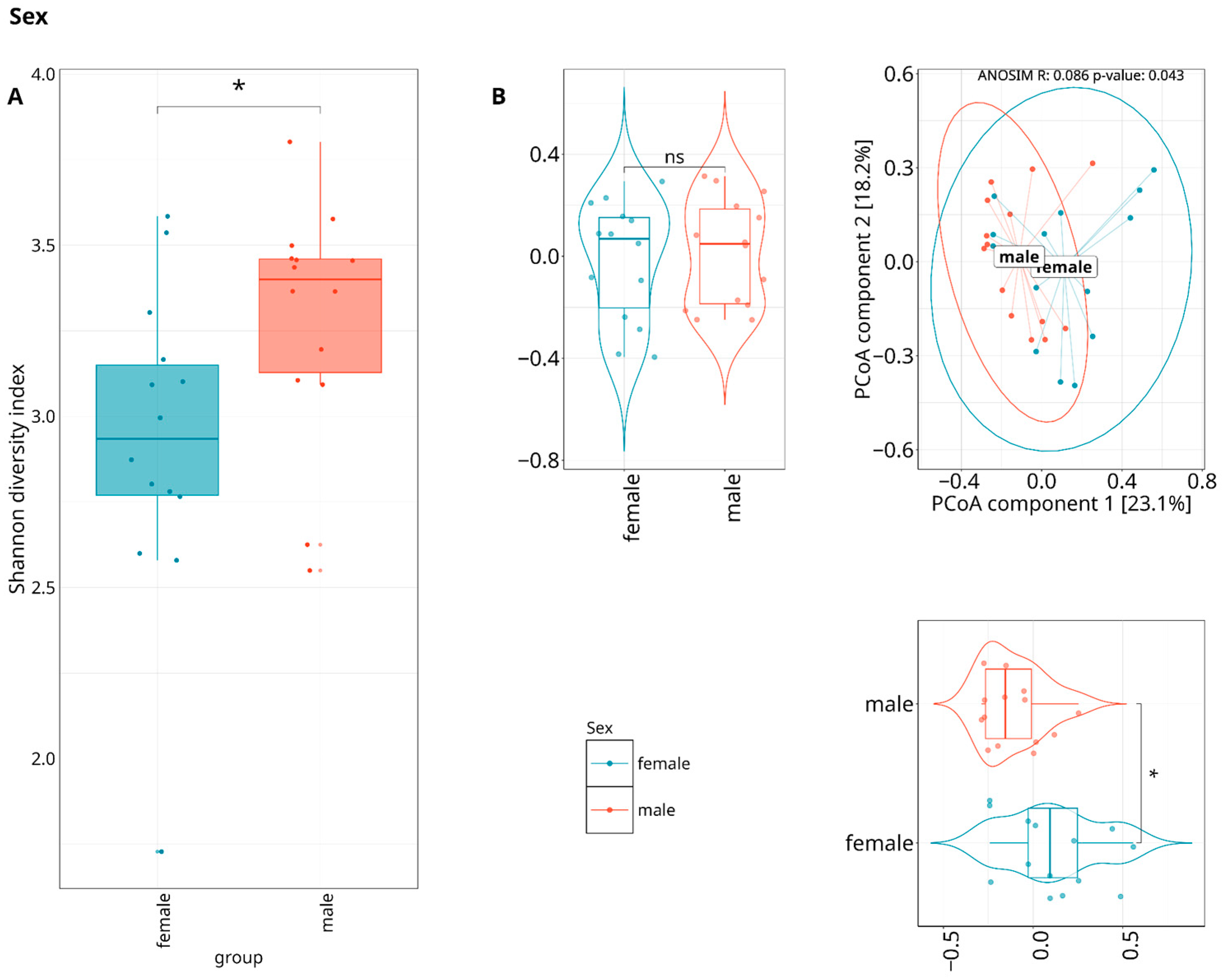

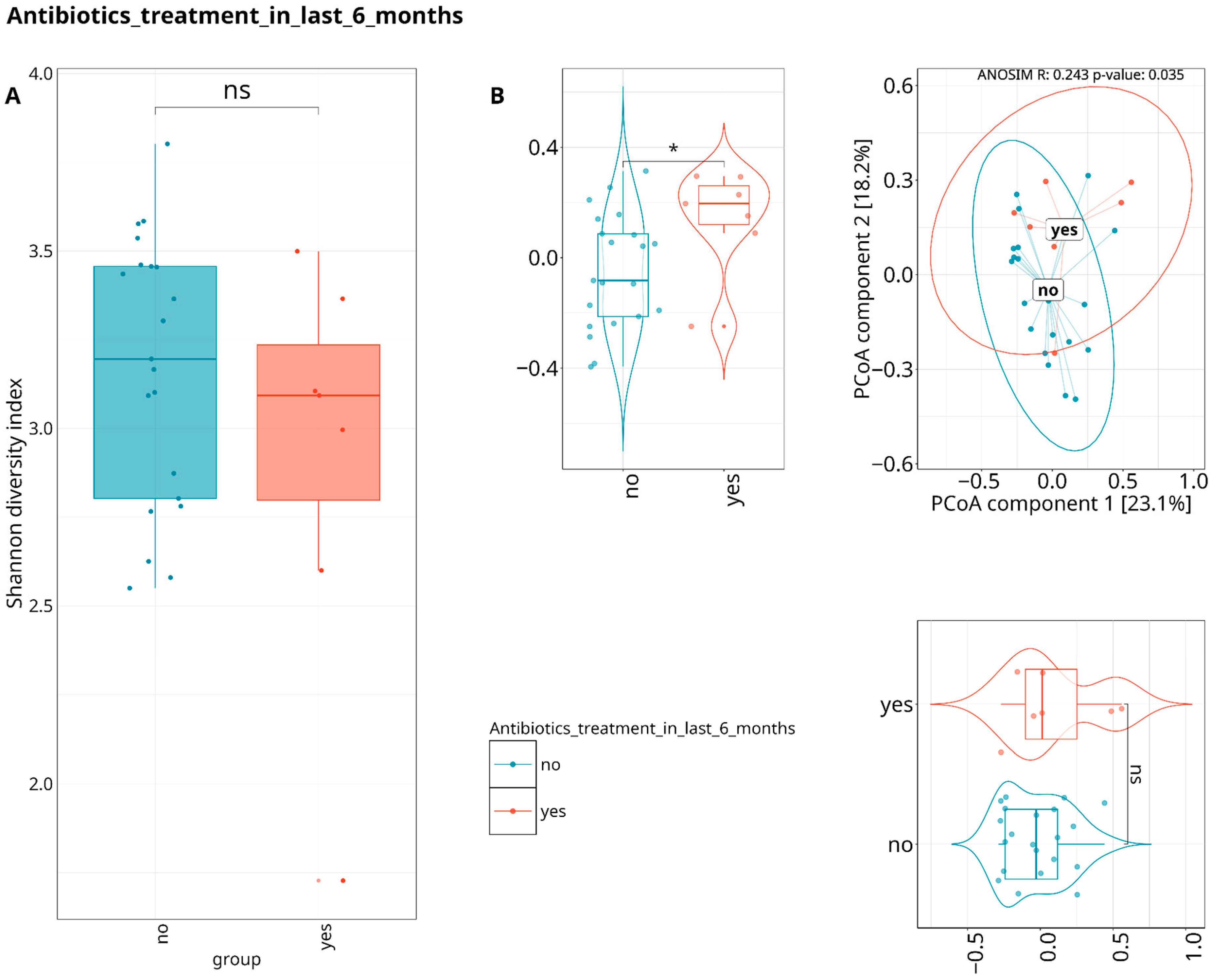

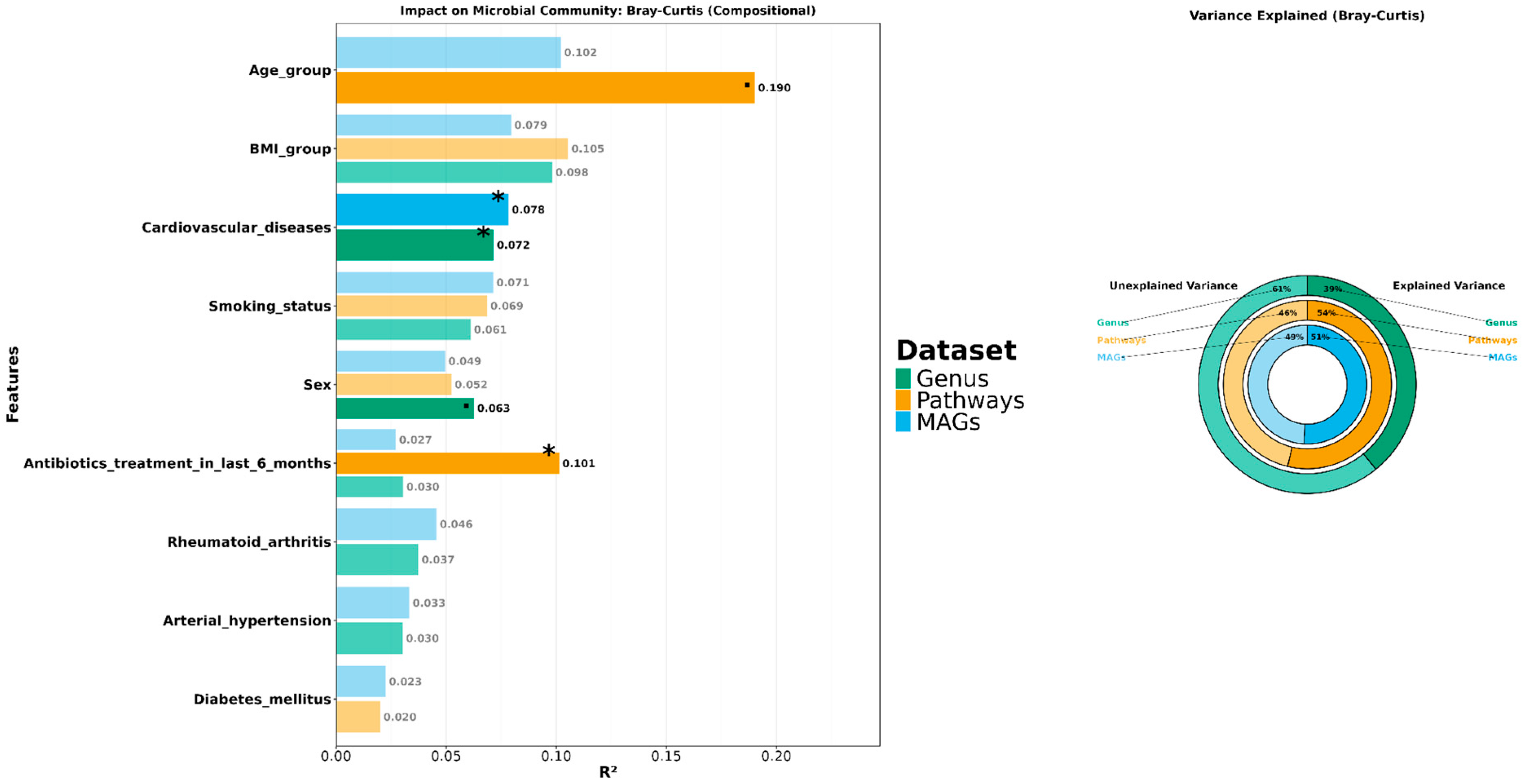

3.3. Exploring the Relationship Between the Periodontal Microbiome and Covariates

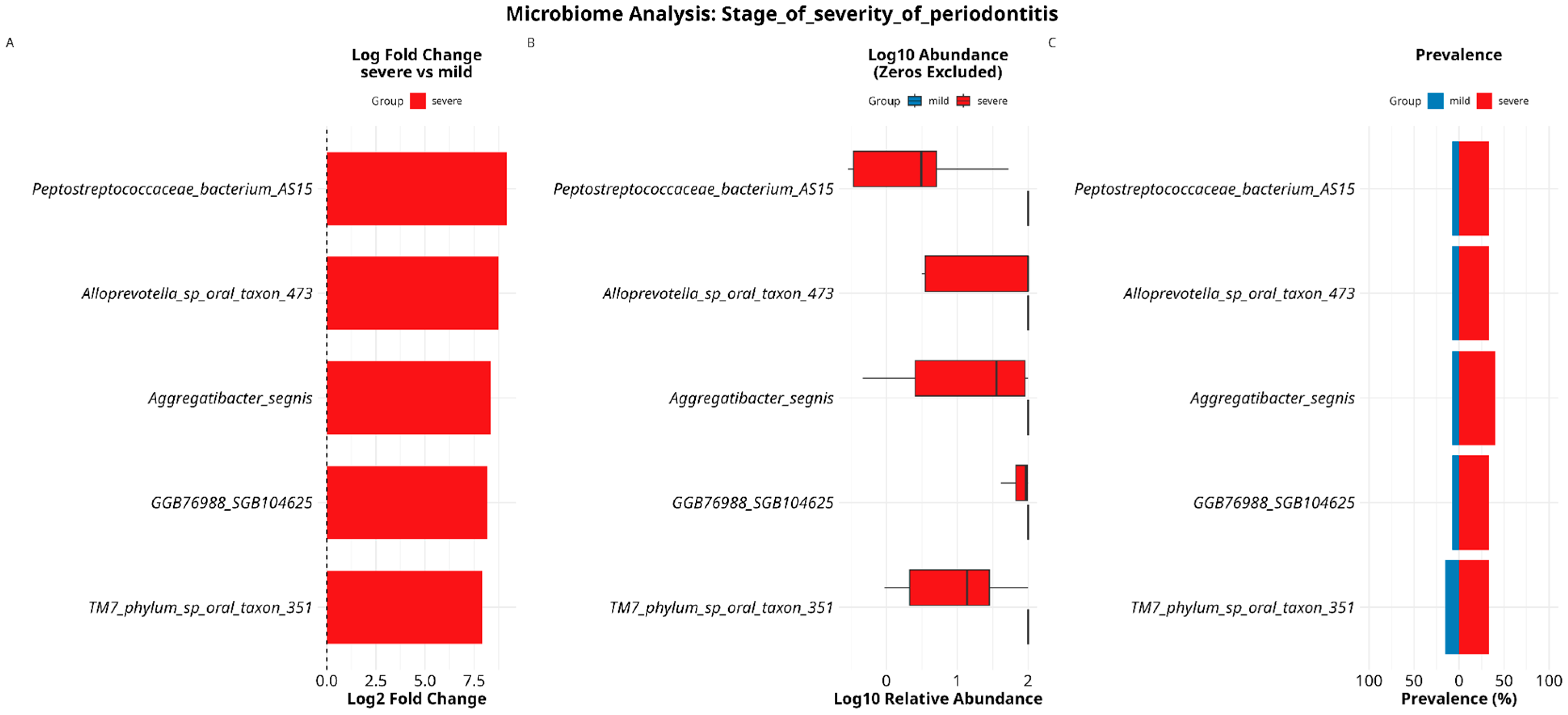

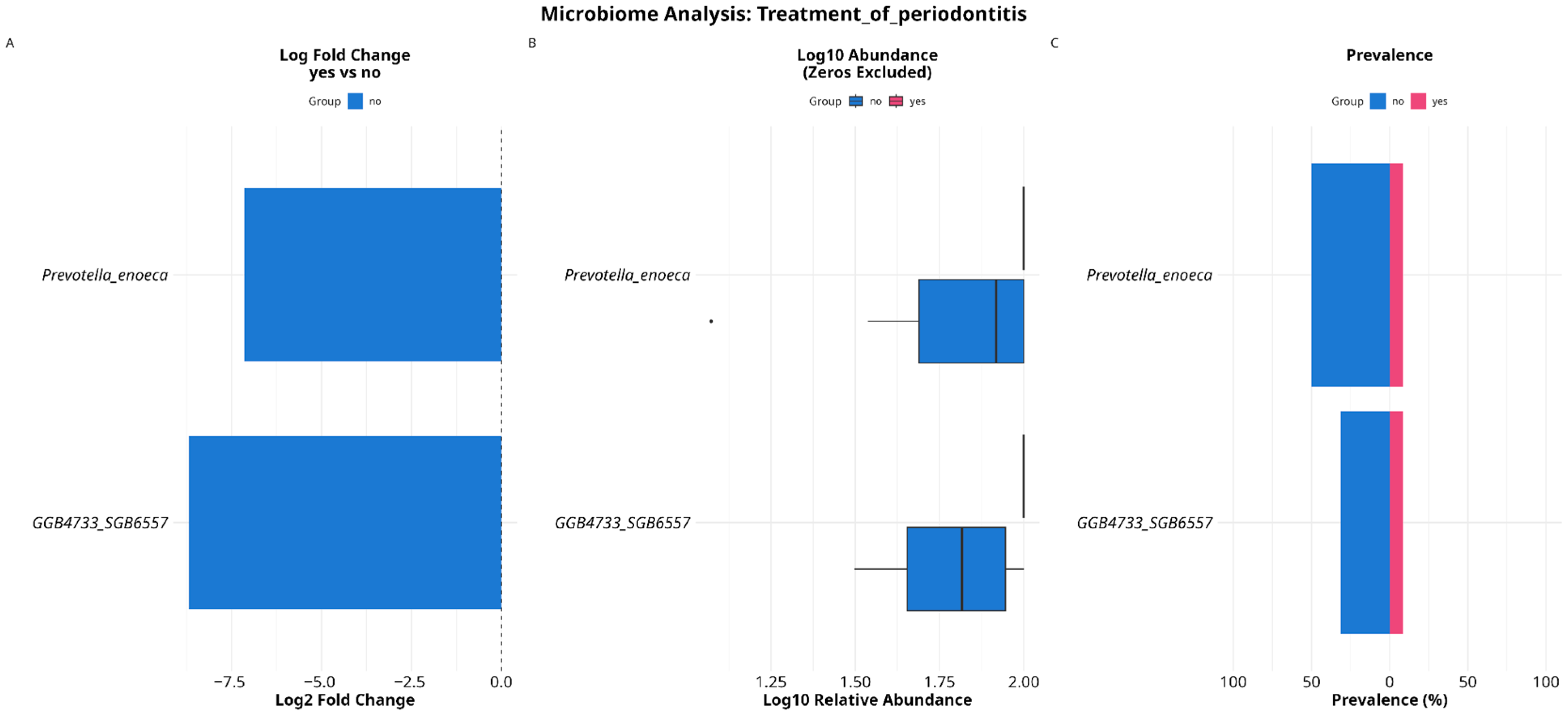

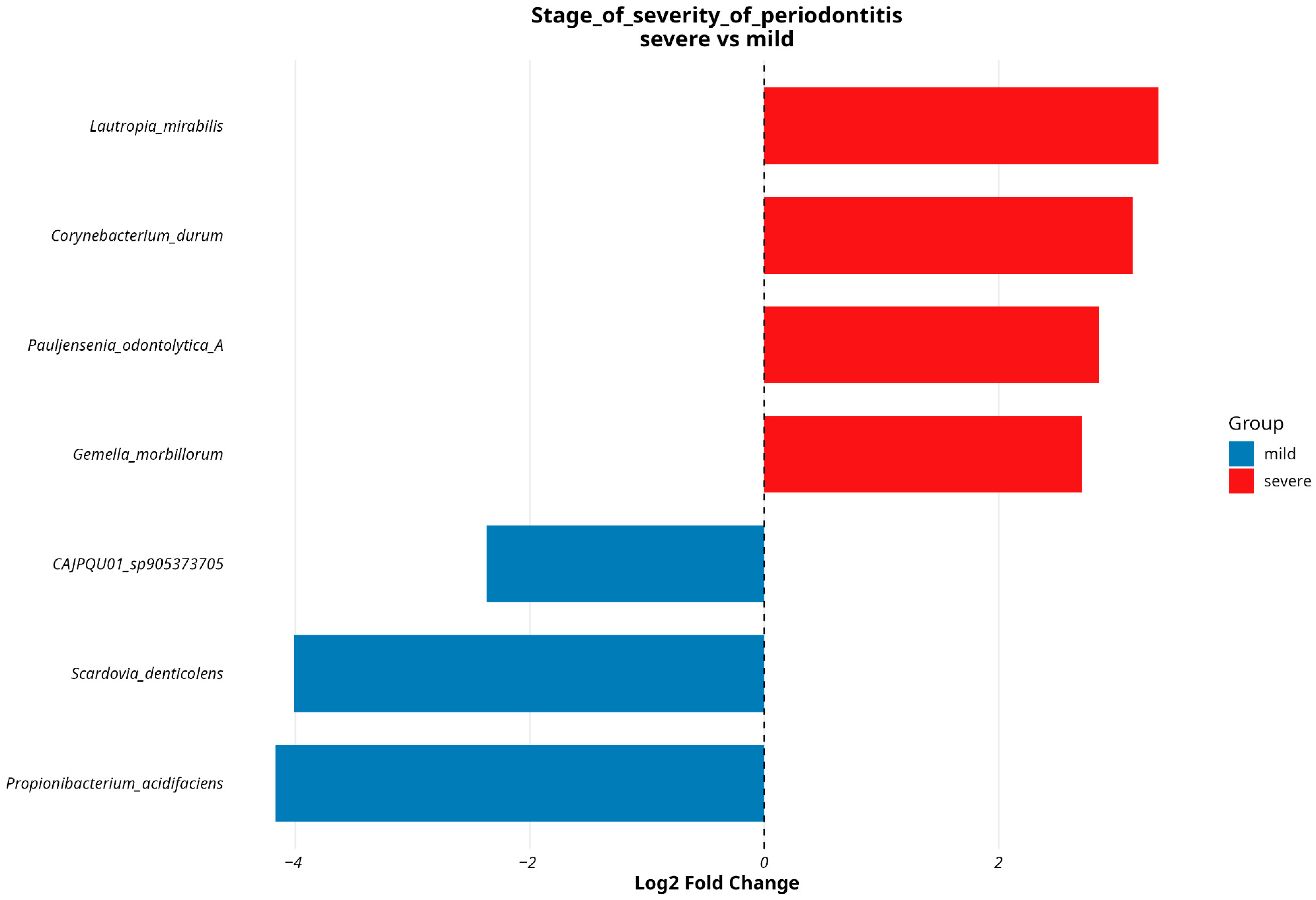

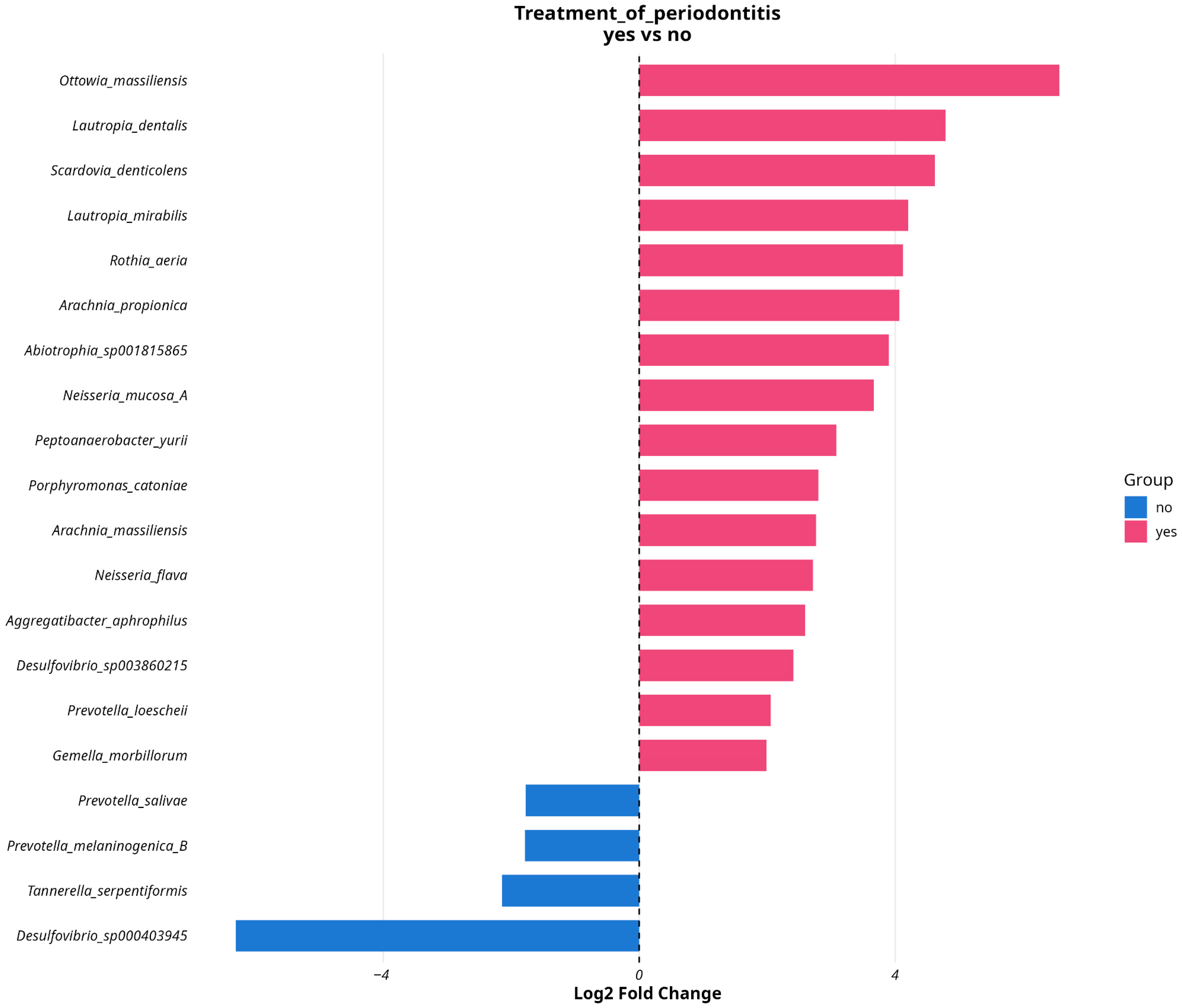

3.4. Analyzing Microbial Associations with Disease Severity in Relation to Variables and Comorbidities

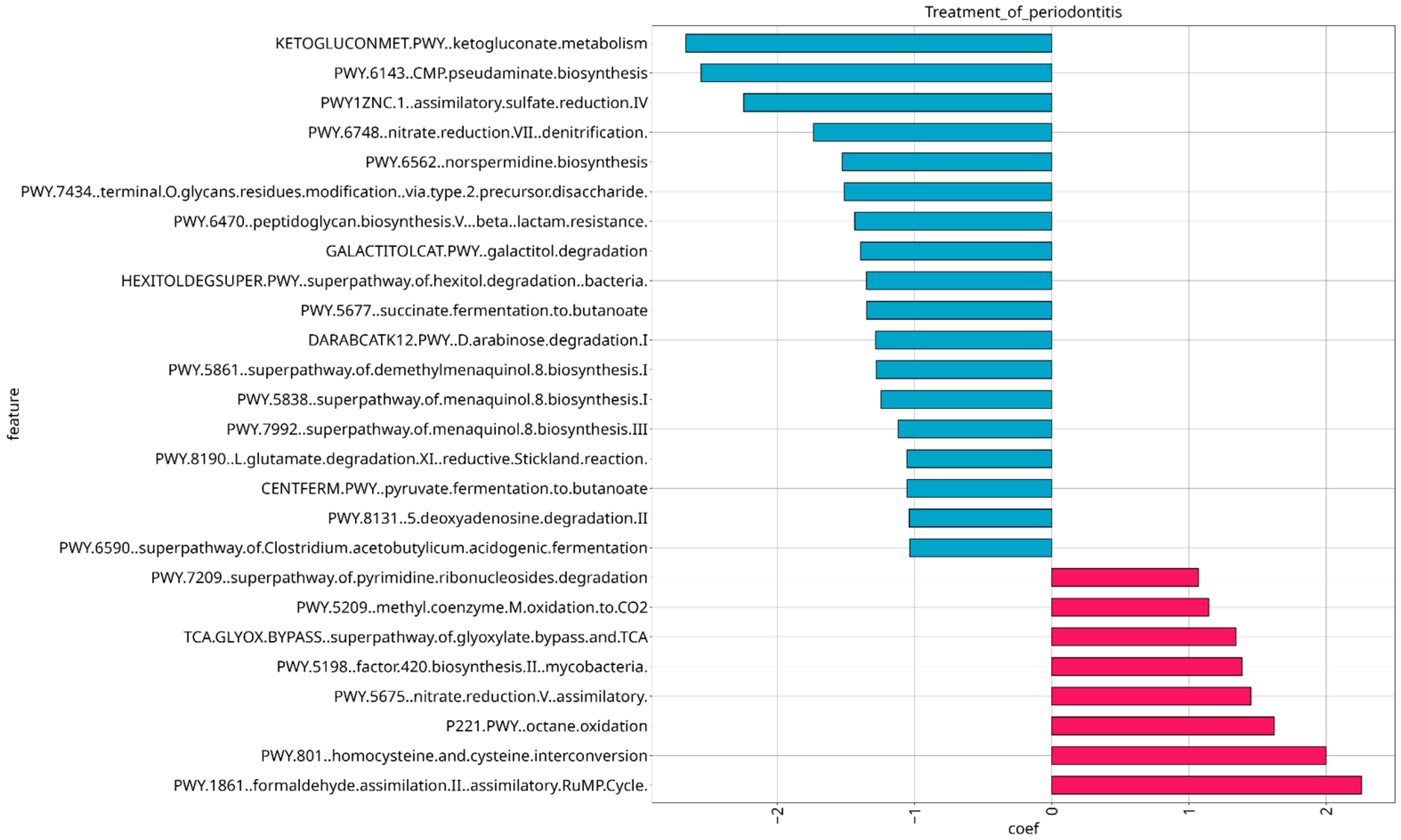

3.5. Analysis of Microbial Functional Composition in Relation to Stage of Severity and Treatment of Periodontitis

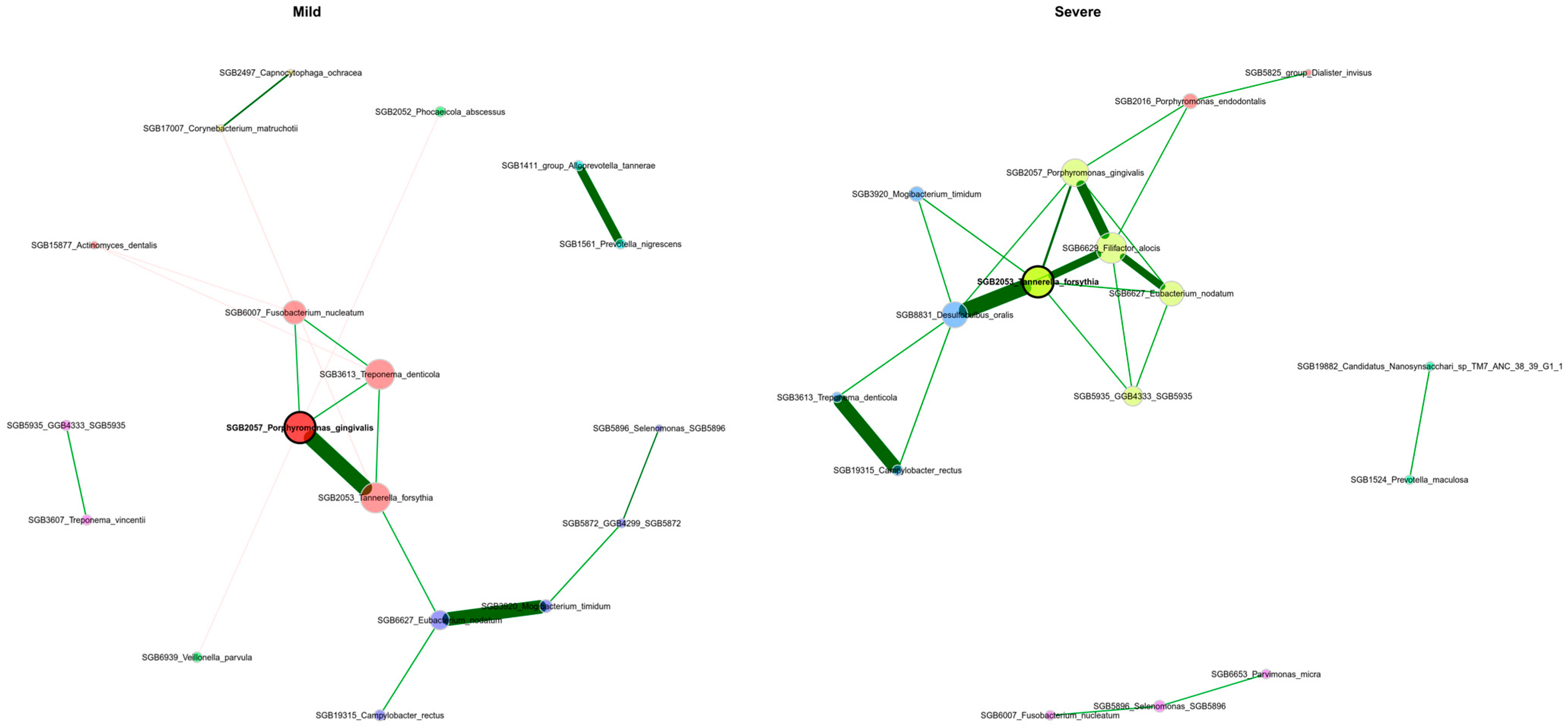

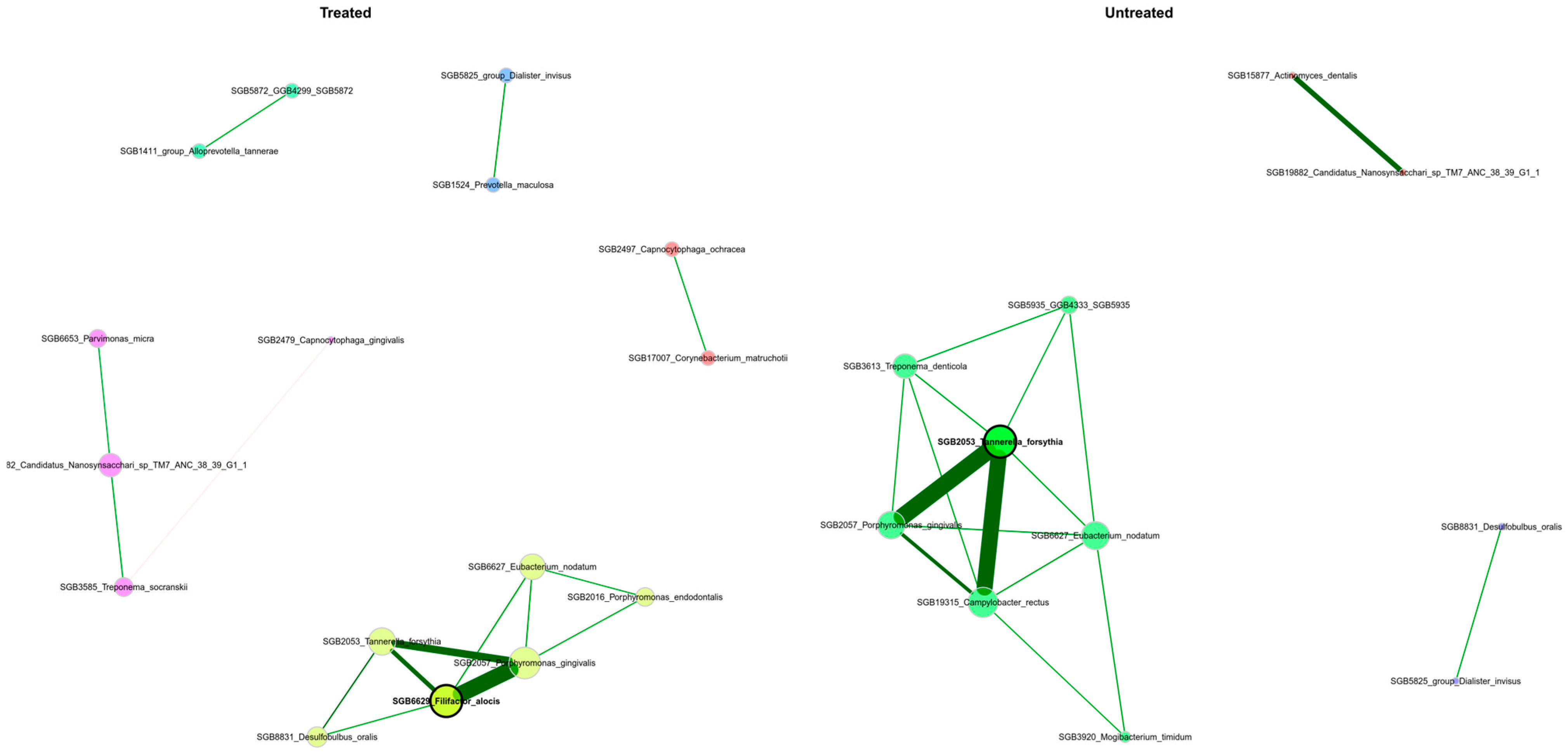

3.6. The Periodontal Microbiota’s Network Structure Shows Variations Across Patients with Differing Severity Levels

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ossowska, A.; Kusiak, A.; Świetlik, D. Evaluation of the Progression of Periodontitis with the Use of Neural Networks. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, D.S.F.; Goh, E.X.J.; Ong, M.M.A.; Preshaw, P.M. Risk factors for tooth loss and progression of periodontitis in patients undergoing periodontal maintenance therapy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W. Global Burden of Severe Periodontitis in 1990–2010: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liccardo, D.; Cannavo, A.; Spagnuolo, G.; Ferrara, N.; Cittadini, A.; Rengo, C.; Rengo, G. Periodontal Disease: A Risk Factor for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: From microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Garg, P.K.; Dubey, A.K. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Song, Z. The Oral Microbiota: Community Composition, Influencing Factors, Pathogenesis, and Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Ohara, N. Molecular mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis-host cell interaction on periodontal diseases. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2017, 53, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Blanco-Pintos, T.; Tomás, I. Critical review of 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow in microbiome studies: From primer selection to advanced data analysis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 347–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Rani, A.; Metwally, A.; McGee, H.S.; Perkins, D.L. Analysis of the microbiome: Advantages of whole genome shotgun versus 16S amplicon sequencing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, L.; de Leeuw, R.H.; Kraakman, M.E.; Pappas, N.; Raa, M.T.; Mei, H.; de Knijff, P.; Laros, J.F. Taxonomic classification and abundance estimation using 16S and WGS—A comparison using controlled reference samples. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 1022, 2020, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiber, M.L.; Taft, D.H.; Korf, I.; Mills, D.A.; Lemay, D.G. Pre- and post-sequencing recommendations for functional annotation of human fecal metagenomes. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gweon, H.S.; Shaw, L.P.; Swann, J.; De Maio, N.; AbuOun, M.; Niehus, R.; Hubbard, A.T.M.; Bowes, M.J.; Bailey, M.J.; Peto, T.E.A.; et al. The impact of sequencing depth on the inferred taxonomic composition and AMR gene content of metagenomic samples. Environ. Microbiome 2019, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Zhong, Q.; Xia, Y. Analysis and evaluation of different sequencing depths from 5 to 20 million reads in shotgun metagenomic sequencing, with optimal minimum depth being recommended. Genome 2022, 65, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; Beghini, F.; Cumbo, F.; McIver, L.J.; Thompson, K.N.; Zolfo, M.; Manghi, P.; Dubois, L.; Huang, K.D.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghini, F.; McIver, L.J.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Dubois, L.; Asnicar, F.; Maharjan, S.; Mailyan, A.; Manghi, P.; Scholz, M.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. eLife 2021, 10, e65088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Li, F.; Kirton, E.; Thomas, A.; Egan, R.; An, H.; Wang, Z. MetaBAT 2: An adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olm, M.R.; Brown, C.T.; Brooks, B.; Banfield, J.F. dRep: A tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2864–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olm, M.R.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Firek, B.A.; Morowitz, M.J.; Banfield, J.F. inStrain profiles population microdiversity from metagenomic data and sensitively detects shared microbial strains. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroney, S.T.N.; Newell, R.J.P.; Nissen, J.N.; Camargo, A.P.; Tyson, G.W.; Woodcroft, B.J. CoverM: Read alignment statistics for metagenomics. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. GTDB: An ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D785–D794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. DESeq2. Bioconductor. 2017. Available online: https://bioconductor.statistik.tu-dortmund.de/packages/3.9/bioc/html/DESeq2.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Peschel, S.; Müller, C.L.; Von Mutius, E.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Depner, M. NetCoMi: Network construction and comparison for microbiome data in R. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, H.; Rahnavard, A.; McIver, L.J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tickle, T.L.; Weingart, G.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.H.; et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, J.; Berggreen, E.; Bunæs, D.F.; Bolstad, A.I.; Bertelsen, R.J. Microbiome composition and metabolic pathways in shallow and deep periodontal pockets. Sci. Rep. 1292, 2025, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, B.; Fazal, I.; Khan, S.F.; Nambiar, M.; D, K.I.; Prasad, R.; Raj, A. Association between cardiovascular diseases and periodontal disease: More than what meets the eye. Drug Target Insights 2023, 17, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.V.H.; Johnson, J.L.; Moore, W.E.C. Descriptions of Prevotella tannerae sp. nov. and Prevotella enoeca sp. nov. from the Human Gingival Crevice and Emendation of the Description of Prevotella zoogleoformans. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994, 44, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Liu, B.; Gao, X.; Xing, K.; Xie, L.; Guo, T. Metagenomic Analysis of Saliva Reveals Disease-Associated Microbiotas in Patients with Periodontitis and Crohn’s Disease-Associated Periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 719411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørskov-Lauritsen, N.; Kilian, M. Reclassification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Haemophilus aphrophilus, Haemophilus paraphrophilus and Haemophilus segnis as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans gen. nov., comb. nov., Aggregatibacter aphrophilus comb. nov. and Aggregatibacter segnis comb. nov., and emended description of Aggregatibacter aphrophilus to include V factor-dependent and V factor-independent isolates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2135–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, T.H.; Powers, C.; McPartland, M.J.; Welch, J.M.; Ramsey, M. Essential genes for Haemophilus parainfluenzae survival and biofilm growth. mSystems 2024, 9, e00674-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, A.; Lucey, O.; Eckersley, M.; Ciesielczuk, H.; Ranasinghe, S.; Lambourne, J. Invasive Aggregatibacter infection: Shedding light on a rare pathogen in a retrospective cohort analysis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, E.; Shiba, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Suda, W.; Nakasato, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Azuma, M.; Hattori, M.; Izumi, Y. Japanese subgingival microbiota in health vs disease and their roles in predicted functions associated with periodontitis. Odontology 2020, 108, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.P.V.; Boches, S.K.; Cotton, S.L.; Goodson, J.M.; Kent, R.; Haffajee, A.D.; Socransky, S.S.; Hasturk, H.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Dewhirst, F.; et al. Comparisons of Subgingival Microbial Profiles of Refractory Periodontitis, Severe Periodontitis, and Periodontal Health Using the Human Oral Microbe Identification Microarray. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreth, J.; Helliwell, E.; Treerat, P.; Merritt, J. Molecular commensalism: How oral corynebacteria and their extracellular membrane vesicles shape microbiome interactions. Front. Oral Health 1410, 2024, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Oge, S.; Nakata, S.; Ueno, Y.; Ukita, H.; Kousaka, R.; Miura, Y.; Yoshinari, N.; Yoshida, A. Gemella haemolysans inhibits the growth of the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 1174, 2021, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könönen, E. Polymicrobial infections with specific Actinomyces and related organisms, using the current taxonomy. J. Oral Microbiol. 2024, 16, 2354148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhi, Q.; Lin, H. Metagenomic Analysis of Dental Plaque on Pit and Fissure Sites With and Without Caries Among Adolescents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 740981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, W.; Dong, X. Transfer of Bifidobacterium inopinatum and Bifidobacterium denticolens to Scardovia inopinata gen. nov., comb. nov., and Parascardovia denticolens gen. nov., comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-hebshi, N.N.; Abdulhaq, A.; Albarrag, A.; Basode, V.K.; Chen, T. Species-level core oral bacteriome identified by 16S rRNA pyrosequencing in a healthy young Arab population. J. Oral Microbiol. 2016, 8, 31444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, U.; Nikolic, N.; Carkic, J.; Mihailovic, D.; Jelovac, D.; Milasin, J.; Pucar, A. Streptococcus mitis and Prevotella melaninogenica Influence Gene Expression Changes in Oral Mucosal Lesions in Periodontitis Patients. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Sato, K.; Nagano, K.; Nishiguchi, M.; Hoshino, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Nakayama, K. Involvement of PorK, a component of the type IX secretion system, in Prevotella melaninogenica pathogenicity. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 62, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Garg, N.; Hasan, S.; Shirodkar, S. Prevotella: An insight into its characteristics and associated virulence factors. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 169, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendlbacher, F.L.; Bloch, S.; Hager-Mair, F.F.; Bacher, J.; Janesch, B.; Thurnheer, T.; Andrukhov, O.; Schäffer, C. Multispecies biofilm behavior and host interaction support the association of Tannerella serpentiformis with periodontal health. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaloum, M.; Lo, C.I.; Ndongo, S.; Meng, M.M.; Saile, R.; Alibar, S.; Raoult, D.; Fournier, P.-E. Ottowia massiliensis sp. nov., a new bacterium isolated from a fresh, healthy human fecal sample. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Kang, M.; Chen, K.; Liang, Q.; Lu, X. A case report of bacterial canaliculitis caused by Ottowia massiliensis Sp.nov. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.K.; Park, S.-N.; Lee, W.-P.; Shin, J.H.; Jo, E.; Shin, Y.; Paek, J.; Chang, Y.-H.; Kim, H.; Kook, J.-. K Lautropia dentalis sp. nov., Isolated from Human Dental Plaque of a Gingivitis Lesion. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, M.; Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Salazar, F.; Pacheco, J.J.; Cabral, C.; Henriques, C.; Tomás, I. Relationship between dental and periodontal health status and the salivary microbiome: Bacterial diversity, co-occurrence networks and predictive models. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabdeen, H.R.Z.; Mustafa, M.; Hasturk, H.; Klepac-Ceraj, V.; Ali, R.W.; Paster, B.J.; Van Dyke, T.; Bolstad, A.I. Subgingival microbial profiles of Sudanese patients with aggressive periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2015, 50, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenartova, M.; Tesinska, B.; Janatova, T.; Hrebicek, O.; Mysak, J.; Janata, J.; Najmanova, L. The Oral Microbiome in Periodontal Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 629723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurel, D.; Carda-Diéguez, M.; Langenburg, T.; Žiemytė, M.; Johnston, W.; Martínez, C.P.; Albalat, F.; Llena, C.; Al-Hebshi, N.; Culshaw, S.; et al. Nitrate and a nitrate-reducing Rothia aeria strain as potential prebiotic or synbiotic treatments for periodontitis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, B.T.; Johnston, W.; Carda-Diéguez, M.; Simpson, A.; Cabello-Yeves, E.; Piela, K.; Reilly, R.; Artacho, A.; Easton, C.; Burleigh, M.; et al. Nitrate reduction capacity of the oral microbiota is impaired in periodontitis: Potential implications for systemic nitric oxide availability. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioguardi, M.; Alovisi, M.; Crincoli, V.; Aiuto, R.; Malagnino, G.; Quarta, C.; Laneve, E.; Sovereto, D.; Russo, L.L.; Troiano, G.; et al. Prevalence of the Genus Propionibacterium in Primary and Persistent Endodontic Lesions: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkacemi, S.; Lagier, J.-C.; Fournier, P.-E.; Raoult, D.; Khelaifia, S. Neoactinobaculum massilliense gen. nov., a new genesis and Pseudopropionibacterium massiliense sp. nov., a new bacterium isolated from the human oral microbiota. New Microbes New Infect. 2019, 32, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Juzbašić, M.; Meštrović, T.; Matijević, T.; Mesarić, D.; Katalinić, D.; Erić, S.; Milostić-Srb, A.; Flam, J.; Škrlec, I. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: From the Oral Cavity to the Heart Valves. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; Guerra, C.; Laterza, P.; Illuzzi, G.; Sovereto, D.; Laneve, E.; Martella, A.; Muzio, L.L.; Ballini, A. Mapping Review of the Correlations Between Periodontitis, Dental Caries, and Endocarditis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könönen, E.; Fteita, D.; Gursoy, U.K.; Gursoy, M. Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J. Oral Microbiol. 2022, 14, 2079814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaghdadi, S.Z.; Altaher, J.B.; Drobiova, H.; Bhardwaj, R.G.; Karched, M. In vitro Characterization of Biofilm Formation in Prevotella Species. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 724194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pussinen, P.J.; Kopra, E.; Pietiäinen, M.; Lehto, M.; Zaric, S.; Paju, S.; Salminen, A. Periodontitis and cardiometabolic disorders: The role of lipopolysaccharide and endotoxemia. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, W.S.; Solon, I.G.; Branco, L.G.S. Impact of Periodontal Lipopolysaccharides on Systemic Health: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 40, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basic, A.; Dahlén, G. Microbial metabolites in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases: A narrative review. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1210200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.-H.; Lu, C.-D. Polyamine Effects on Antibiotic Susceptibility in Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruni, A.W.; Mishra, A.; Dou, Y.; Chioma, O.; Hamilton, B.N.; Fletcher, H.M. Filifactor alocis—A new emerging periodontal pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, K.L.; Chirania, P.; Xiong, W.; Beall, C.J.; Elkins, J.G.; Giannone, R.J.; Griffen, A.L.; Guss, A.M.; Hettich, R.L.; Joshi, S.S.; et al. Insights into the Evolution of Host Association through the Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Human Periodontal Pathobiont, Desulfobulbus oralis. mBio 2018, 9, e02061-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, H.; Miura, T.; Kato, T.; Ishihara, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Yamada, S.; Okuda, K. Detection of Campylobacter rectus in periodontitis sites by monoclonal antibodies. J. Periodontal Res. 2003, 38, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeishi, H.; Hamada, N.; Kaneyasu, Y.; Niitani, Y.; Takemoto, T.; Ohta, K. Prevalence of oral Capnocytophaga species and their association with dental plaque accumulation and periodontal inflammation in middle-aged and older people. Biomed. Rep. 2024, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Umeda, M.; Ishikawa, I.; Benno, Y.; Nakase, T. Detection of Treponema socranskii Associated with Human Periodontitis by PCR. Microbiol. Immunol. 1999, 43, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikarkhane, V.; Dodwad, V.; Patankar, S.A.; Pharne, P.; Bhosale, N.; Patankar, A. Comparative Evaluation of Mogibacterium timidum in the Subgingival Plaque of Periodontally Healthy and Chronic Periodontitis Patients: A Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e61211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffajee, A.D.; Teles, R.P.; Socransky, S.S. Association of Eubacterium nodatum and Treponema denticola with human periodontitis lesions. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2006, 21, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Weight | 90.21 | 58 | 110 | 17.75 |

| Height | 178.36 | 168 | 188 | 6.68 | |

| BMI | 26.56 | 20.55 | 33.90 | 4.53 | |

| Female | Weight | 69.08 | 53 | 89 | 10.66 |

| Height | 169.15 | 150 | 185 | 8.93 | |

| BMI | 24.12 | 19.71 | 29.98 | 3.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonets, I.V.; Galeeva, I.S.; Krivonos, D.V.; Pavlenko, A.V.; Vvedenskiy, A.V.; Ahmetzyanova, A.A.; Mikaelyan, K.A.; Ilina, E.N.; Yanushevich, O.O.; Revazova, Z.E.; et al. In-Depth Multi-Approach Analysis of WGS Metagenomics Data Reveals Signatures Potentially Explaining Features in Periodontitis Stage Severity. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120590

Sonets IV, Galeeva IS, Krivonos DV, Pavlenko AV, Vvedenskiy AV, Ahmetzyanova AA, Mikaelyan KA, Ilina EN, Yanushevich OO, Revazova ZE, et al. In-Depth Multi-Approach Analysis of WGS Metagenomics Data Reveals Signatures Potentially Explaining Features in Periodontitis Stage Severity. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120590

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonets, Ignat V., Iulia S. Galeeva, Danil V. Krivonos, Alexander V. Pavlenko, Andrey V. Vvedenskiy, Anna A. Ahmetzyanova, Karen A. Mikaelyan, Elena N. Ilina, Oleg O. Yanushevich, Zalina E. Revazova, and et al. 2025. "In-Depth Multi-Approach Analysis of WGS Metagenomics Data Reveals Signatures Potentially Explaining Features in Periodontitis Stage Severity" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120590

APA StyleSonets, I. V., Galeeva, I. S., Krivonos, D. V., Pavlenko, A. V., Vvedenskiy, A. V., Ahmetzyanova, A. A., Mikaelyan, K. A., Ilina, E. N., Yanushevich, O. O., Revazova, Z. E., Vibornaya, E. I., Runova, G. S., Aliamovskii, V. V., Bobr, I. S., Tsargasova, M. O., Kalinnikova, E. I., & Govorun, V. M. (2025). In-Depth Multi-Approach Analysis of WGS Metagenomics Data Reveals Signatures Potentially Explaining Features in Periodontitis Stage Severity. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120590