Accuracy of Surgical Guides in Guided Apical Surgery: An In Vitro Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Sample and Teeth Selection

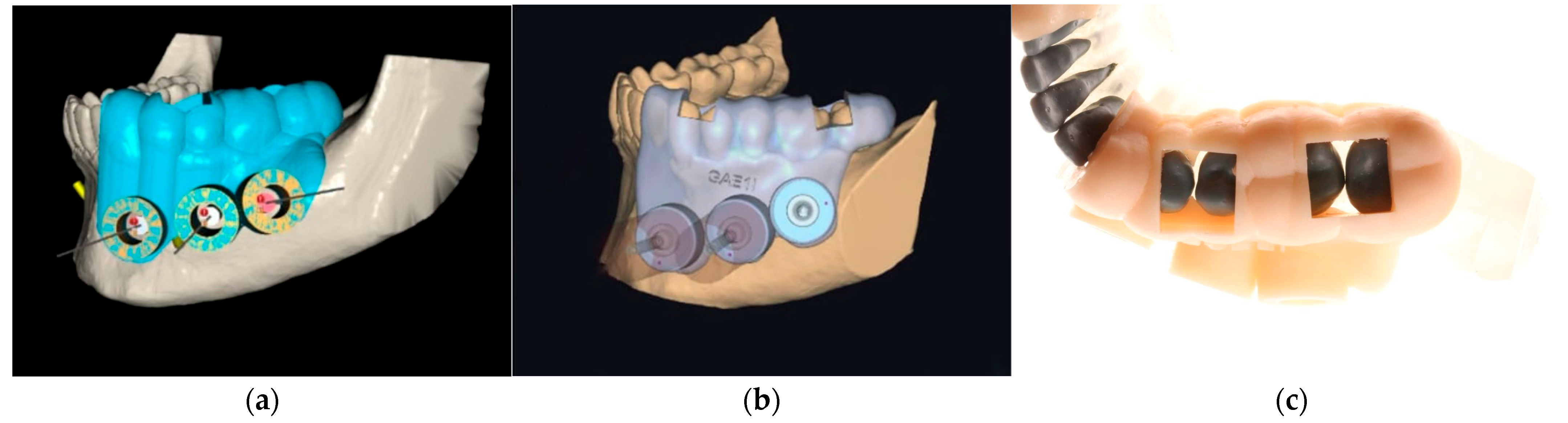

2.3. Surgical Guide Design and Software Versions

2.4. Guide Fabrication and Quality Control

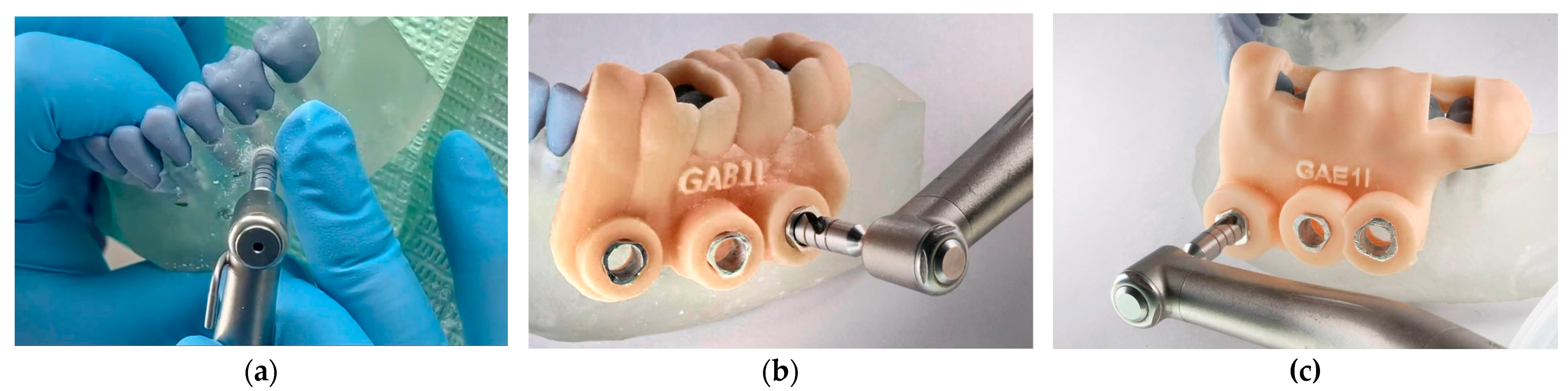

2.5. Trephination Procedure

2.6. Operator Calibration and Randomisation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Stability

3.2. Accuracy

3.3. Operative Time

3.4. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| GE | Guided Endodontics |

| SGE | Static Guided Endodontics |

| DGE | Dynamic Guided Endodontics |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

References

- Setzer, F.C.; Kratchman, S.I. Present status and future directions: Surgical endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. 4), 1020–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.K.; Wealleans, J.A.; Pratt, A.M.; Ray, J.J. Targeted endodontic microsurgery and endodontic microsurgery: A surgical simulation comparison. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Wealleans, J.; Ray, J. Endodontic applications of 3D printing. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomino, C.M.; Ray, J.J.; Wealleans, J.A. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Novel Approach to Anatomically Challenging Scenarios Using 3-dimensional-printed Guides and Trephine Burs-A Report of 3 Cases. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Qin, L.; Zhang, R.; Meng, L. Comparison of Accuracy and Operation Time in Robotic, Dynamic, and Static-Assisted Endodontic Microsurgery: An In Vitro Study. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, M.S.; Connert, T.; Weiger, R.; Krastl, G.; Kuhl, S. Guided endodontics: Accuracy of a novel method for guided access cavity preparation and root canal location. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Gadhiraju, S.; Quraishi, A.; Kamishetty, S. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Guided Approach—A Report of Two Cases. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2022, 13, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Amato, M.; Weiger, R.; Kuhl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: A method to achieve minimally invasive access cavity preparation and root canal location in mandibular incisors using a novel computer-guided technique. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rabie, C.; Torres, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Jacobs, R. Clinical applications, accuracy and limitations of guided endodontics: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde Haro, H.P.; Quille Punina, L.G.; Erazo Conde, A.D. Guided Endodontic Treatment of Mandibular Incisor with Pulp Canal Obliteration following Dental Trauma: A Case Report. Iran. Endod. J. 2024, 19, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.D.; Saunders, M.W.; Carrico, C.K.; Jadhav, A.; Deeb, J.G.; Myers, G.L. Dynamically Navigated versus Freehand Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using Simulated Calcified Canals. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A.; Santosh, S.S.; Selvakumar, R.J.; Sampath, D.T.; Natanasabapathy, V. Dynamic Navigation in Guided Endodontics—A Systematic Review. Eur. Endod. J. 2022, 7, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, K.C.; Borkowski, L.; Liebermann, A.; Berlinghoff, F.; Hickel, R.; Schwendicke, F.; Reymus, M. Comparing accuracy in guided endodontics: Dynamic real-time navigation, static guides, and manual approaches for access cavity preparation—An in vitro study using 3D printed teeth. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Peng, L.; Zhao, Y.J.; Han, B.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, Z.H. Accuracy and efficiency of dynamic navigated root-end resection in endodontic surgery: A pilot in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Xie, W.; Li, T.; Wang, A.; Wu, L.; Kang, W.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Tang, X.; Xie, S. New-designed 3D printed surgical guide promotes the accuracy of endodontic microsurgery: A study of 14 upper anterior teeth. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coachman, C.; Georg, R.; Bohner, L.; Rigo, L.C.; Sesma, N. Chairside 3D digital design and trial restoration workflow. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezon, C.; Aubeux, D.; Pérez, F.; Gaudin, A. 3D-Printed Metal Surgical Guide for Endodontic Microsurgery (a Proof of Concept). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.W.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Hu, K.S.; Kim, E. Accuracy of 3-dimensional surgical guide for endodontic microsurgery with a new design concept: A cadaver study. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 58, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connert, T.; Krug, R.; Eggmann, F.; Emsermann, I.; ElAyouti, A.; Weiger, R.; Kuhl, S.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontics versus Conventional Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using 3-dimensional-printed Teeth. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Sun, Y.C.; Liang, Y.H. Accuracy of root-end resection using a digital guide in endodontic surgery: An in vitro study. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strbac, G.D.; Schnappauf, A.; Giannis, K.; Moritz, A.; Ulm, C. Guided Modern Endodontic Surgery: A Novel Approach for Guided Osteotomy and Root Resection. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Reis, E.; Marques, J.A.; Falacho, R.I.; Palma, P.J. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques-A Literature Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniag, A.G.; Pratt, A.M.; Ray, J.J. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Retrospective Outcomes Assessment of 24 Cases. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, A.; Munoz, A.P.; Deglow, E.R.; Agustin-Panadero, R.; Alvarez, J.M. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to Computer-Aided Static Procedure for Endodontic Access Cavities: An in Vitro Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H. Transformative Advances in Digital Orthodontics. Orthod. Craniofac Res. 2024, 27 (Suppl. 2), 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianat, O.; Nosrat, A.; Mostoufi, B.; Price, J.B.; Gupta, S.; Martinho, F.C. Accuracy and efficiency of guided root-end resection using a dynamic navigation system: A human cadaver study. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, A.; Valle Castano, S.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Mena-Alvarez, J. Effect of Computer-Aided Navigation Techniques on the Accuracy of Endodontic Access Cavities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biology 2021, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.; Nagy, E.; Braunitzer, G.; Frater, M.; Piffko, J. Accuracy and clinical safety of guided root end resection with a trephine: A case series. Head. Face Med. 2019, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antal, M.; Nagy, E.; Sanyo, L.; Braunitzer, G. Digitally planned root end surgery with static guide and custom trephine burs: A case report. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2020, 16, e2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, E.; Lotz, M.; Rechenberg, D.K.; Stadlinger, B.; Rucker, M.; Valdec, S. Guided apicoectomy using a CAD/CAM drilling template. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2019, 22, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, S.; Aguilera, F.C.; Buie, J.M.; Glickman, G.N.; Umorin, M.; Wang, Q.; Jalali, P. Accuracy of 3-dimensional-printed Endodontic Surgical Guide: A Human Cadaver Study. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, R.; Reich, S.; Connert, T.; Kess, S.; Soliman, S.; Reymus, M.; Krastl, G. Guided endodontics: A comparative in vitro study on the accuracy and effort of two different planning workflows. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2020, 23, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt, B.; Rieder, M.; Gsaxner, C.; Gaessler, J.; Payer, M.; Wallner, J. Augmented Reality-Guided Apicoectomy Based on Maxillofacial CBCT Scans. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiscsatári, R.; Nagy, E.; Szabó, M.; Braunitzer, G.; Piffkó, J.; Fráter, M.; Antal, M.Á. Comparison of the Three-Dimensional Accuracy of Guided Apicoectomy Performed with a Drill or a Trephine: An In Vitro Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.G.; Pratt, A.M.; Anderson, J.A.; Ray, J.J. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: Implications of the Greater Palatine Artery. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.L.F.; Fonseca, F.O.; Maia, L.M.; de Carvalho Machado, V.; Franca Alves Silva, N.R.; Junior, G.M.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P. 3D Apicoectomy Guidance: Optimizing Access for Apicoectomies. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 357.e1–357.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddoura, R.; Lazkani, T.; Madarati, A.A. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery of a Mandibular First Molar with a Separated Instrument Using the 3D-printed Guide and Trephine Bur: A Case Report with a 2-year Follow-up. Eur. Endod. J. 2025, 10, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lio, F.; Mampieri, G.; Mazzetti, V.; Leggeri, A.; Arcuri, L. Guided endodontic microsurgery in apicoectomy: A review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2021, 35, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Du, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yue, L.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Chen, Z.; Liang, J.; Chen, W.; Qiu, L.; et al. Expert consensus on digital guided therapy for endodontic diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G.R.M.; Peditto, M.; Venticinque, A.; Marciano, A.; Bianchi, A.; Pedulla, E. Advancements in guided surgical endodontics: A scoping review of case report and case series and research implications. Aust. Endod. J. 2024, 50, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | n (Models) | Failures (+) | Proportion (%) | 95% CI for Failures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Control | 8 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| G2 Blue Sky | 8 | 4 | 50.0 | 21.5–78.5 |

| G3 Exoplan | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | 0.7–53.3 |

| Group | Samples (n) | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Control | 24 | −0.77 | 3.14 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 0.82 | 75.4 |

| G2 Blue Sky | 24 | −0.13 | 2.27 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 69.7 |

| G3 Exoplan | 23 * | −0.04 | 0.80 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 115.1 |

| Group | Samples (n) | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Control | 24 | 96.0 | 238.0 | 150.6 | 154.6 | 38.6 | 24.9 |

| G2 Blue Sky | 24 | 59.0 | 181.0 | 132.1 | 127.5 | 34.0 | 26.7 |

| G3 Exoplan | 23 | 54.0 | 135.0 | 114.8 | 106.5 | 22.8 | 21.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero Mora, N.S.; Peñaherrera Manosalvas, M.S.; Valverde Haro, H.P. Accuracy of Surgical Guides in Guided Apical Surgery: An In Vitro Comparative Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120561

Romero Mora NS, Peñaherrera Manosalvas MS, Valverde Haro HP. Accuracy of Surgical Guides in Guided Apical Surgery: An In Vitro Comparative Study. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):561. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120561

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero Mora, Nancy Soraya, Maria Soledad Peñaherrera Manosalvas, and Henry Paul Valverde Haro. 2025. "Accuracy of Surgical Guides in Guided Apical Surgery: An In Vitro Comparative Study" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120561

APA StyleRomero Mora, N. S., Peñaherrera Manosalvas, M. S., & Valverde Haro, H. P. (2025). Accuracy of Surgical Guides in Guided Apical Surgery: An In Vitro Comparative Study. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120561