The Influence of Anxiety on Postoperative Quality of Life Regarding Implant Treatments: An Epidemiological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Context

2.3. Participants

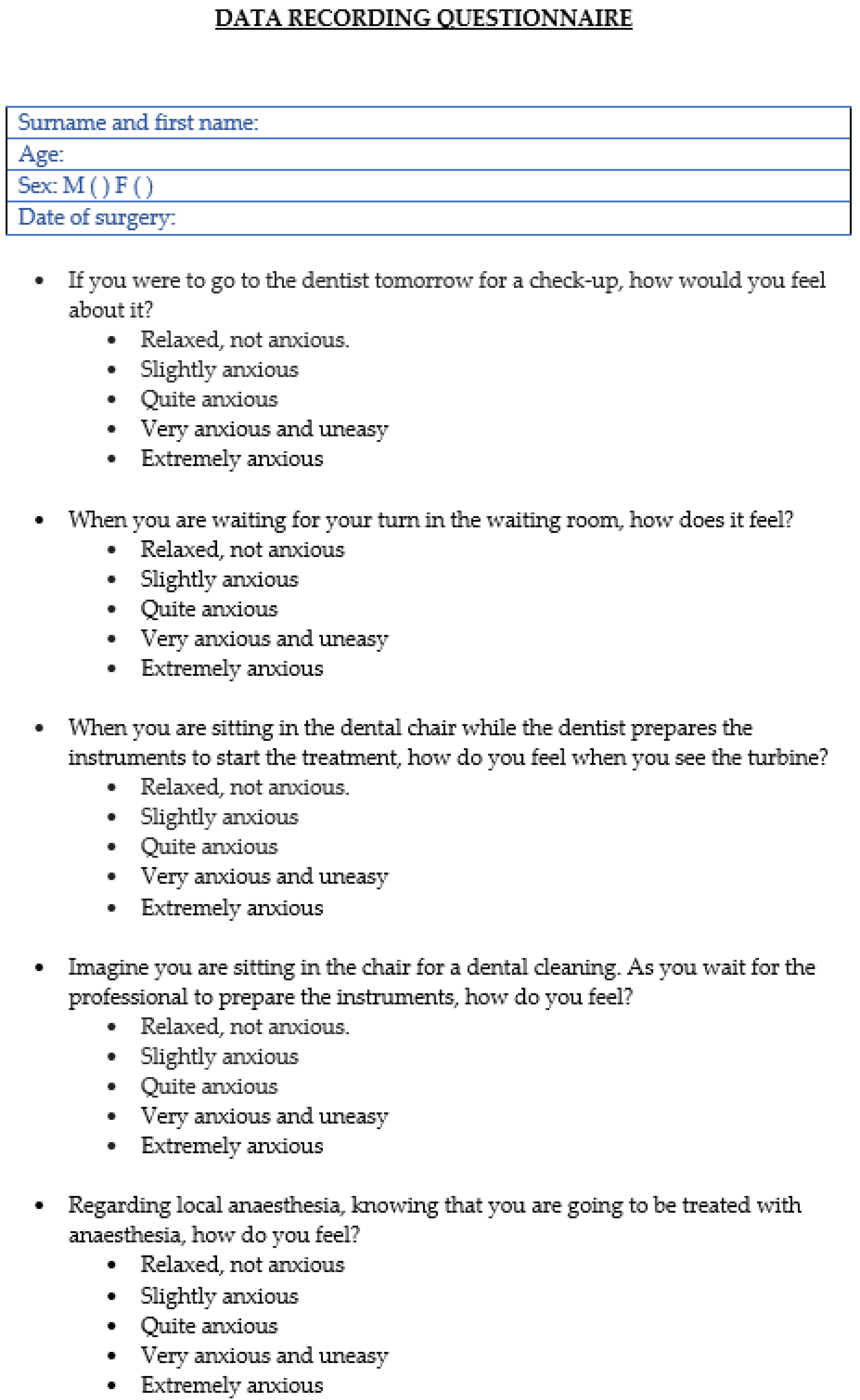

2.4. Variables

2.5. Biases

2.6. Sampling Size

2.7. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Descriptive Data

3.3. Data on Result Variables

3.3.1. Quality of Life

3.3.2. Pain

3.3.3. Swelling

3.3.4. Age

3.3.5. Sex

3.3.6. Tobacco

3.3.7. Number of Implants

3.3.8. Number of Locations and the Different Study Variables

3.3.9. Surgical Time and the Different Study Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corah, N.L.; Gale, E.N.; Illig, S.J. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978, 97, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corah, N.L. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J. Dent. Res. 1969, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.M.; Giblin, L.; Boyd, L.D. The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety in Dental Practice Settings. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 91, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.S.; Wu, S.Y.; Yi, C.A. Association between anxiety and pain in dental treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, B.N.; McNeil, D.W.; Weaver, B.; Wilson, T. Recall of dental pain and anxiety in a cohort of oral surgery patients. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guentsch, A.; Stier, C.; Raschke, G.F.; Peisker, A.; Fahmy, M.D.; Kuepper, H.; Schueler, I. Oral health and dental anxiety in a German practice-based simple. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkling, N.; Marwinski, G.; Johren, P. Dental anxiety in a representative sample of residents of a large German city. Clin. Oral Investig. 2006, 10, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locker, D.; Poulton, R.; Thomson, W.M. Psychological disorders and dental anxiety in a Young adult population. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2001, 29, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muglali, M.; Komerik, N. Factors related to patients’ anxiety before and after oral surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Locker, D.; Poulton, R. Incidence of dental anxiety in Young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2000, 28, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elter, J.R.; Strauss, R.P.; Beck, J.D. Assessing dental anxiety, dental care use and oral status in older adults. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1997, 128, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnarsson, E. Dental fear and anxiety in an adult Icelandic population. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1998, 56, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggirias, J.; Locker, D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2002, 30, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Namankany, A.; de Souza, M.; Ashley, P. Evidence-based dentistry: Analysis of dental anxiety scales for children. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 212, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznar-Arasa, L.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Gay-Escoda, C. Patient anxiety and surgical difficulty in impacted lower third molar extractions: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Ruiz, M.M.; Herrero-Climent, M.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L. Protocolo de control del dolor y la inflamación postquirúrgica: Una aproximación racional. RCOE 2006, 11, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, K.A. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid.-Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deinzer, R.; Granrath, N.; Stuhl, H. Acute stress effects on local Il-1b responses to pathogens in a human in vivo model. Brain Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.H.; Tonami, K.; Umemori, S.; Nguyen, L.B.; Ngo, L.Q.; Araki, K.; Nitta, H. Relationship between preoperative dental anxiety and short-term inflammatory response following oral surgery. Aust. Dent. J. 2021, 66, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidi, H.; Lavaee, F.; Ghapanchi, J.; Golkari, A.; Kholousi, S. The relation of preoperative stress and anxiety on patients’ satisfaction after implant placement. Dent. Res. J. 2017, 14, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Fardal, Ø.; McCulloch, C.A. Impact of anxiety on pain perception associated with periodontal and implant surgery in a private practice. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Qiao, S.C.; Gu, Y.X.; Shi, J.Y.; Lai, H.C. A study on the prevalence of dental anxiety, pain perception, and their interrelationship in Chinese patients with oral implant surgery. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eli, I.; Schwartz-Arad, D.; Baht, R.; Ben-Tuvim, H. Effect of anxiety on the experience of pain in implant insertion. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2003, 14, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrosh, M.Y.; Alhazmi, Y.A.; Aljabri, M.Y.; Bakri, M.M.H.; Al Shawkani, H.A.; Al Moaleem, M.M.; Al-Dhelai, T.A.; Bhandi, S.; Patil, S. A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies Conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on Levels of Dental Anxiety Between Genders and Demographic Groups. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e937470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, P.P.; Strong, V.E.M.; Freeman, T.A.; Winter, J.; Yan, Z.; Daly, J.M. Gender affects macrophage cytokine and prostaglandin E2 production and PGE2 receptor expression after trauma. J. Surg. Res. 2004, 122, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, M.A.C.; Mahon, P.B.; McCaul, M.E.; Wand, G.S. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress: Effects of biological sex and circulating sex hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 66, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B.; Erwood, K.; Ncomanzi, S.; Fischer, V.; O’Brien, D.; Lee, A. Management strategies for adult patients with dental anxiety in the dental clinic: A systematic review. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67 (Suppl. S1), S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quality of Life | Response | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sick leave | Yes | 1 | 1 |

| No | 101 | 99 | |

| Limitations at work | Yes | 6 | 5.9 |

| No | 96 | 94.1 | |

| State of mind | Yes | 7 | 6.9 |

| No | 95 | 93.1 | |

| Weight loss | Yes | 15 | 14.7 |

| No | 87 | 85.3 | |

| Fever | Yes | 3 | 2.9 |

| No | 99 | 2.9 |

| Response | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain during day of surgery | Pain-free | 25 | 24.5 |

| Slight | 41 | 40.2 | |

| Moderate | 24 | 23.5 | |

| Intense | 9 | 8.8 | |

| Maximum | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Pain after 24 h | Pain-free | 34 | 33.3 |

| Slight | 38 | 37.3 | |

| Moderate | 23 | 22.5 | |

| Intense | 5 | 4.9 | |

| Maximum | 2 | 2 | |

| Pain after 48 h | Pain-free | 47 | 46.1 |

| Slight | 40 | 39.2 | |

| Moderate | 9 | 8.8 | |

| Intense | 5 | 4.9 | |

| Maximum | 1 | 1 | |

| Pain after 72 h | Pain-free | 71 | 69.6 |

| Slight | 22 | 21.6 | |

| Moderate | 6 | 5.9 | |

| Intense | 2 | 2 | |

| Maximum | 1 | 1 | |

| Pain the week after | Pain-free | 57 | 55.9 |

| Rarely | 32 | 31.4 | |

| Frequent | 12 | 11.8 | |

| Very frequent | 1 | 1 |

| Response | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swelling during day of surgery | No swelling | 38 | 37.3 |

| Slight | 42 | 41.2 | |

| Moderate | 19 | 18.6 | |

| Intense | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Swelling after 24 h | No swelling | 22 | 21.6 |

| Slight | 41 | 40.2 | |

| Moderate | 32 | 31.4 | |

| Intense | 7 | 6.9 | |

| Swelling after 48 h | No swelling | 36 | 35.3 |

| Slight | 42 | 41.2 | |

| Moderate | 18 | 17.6 | |

| Intense | 6 | 5.9 | |

| Swelling after 72 h | No swelling | 60 | 58.8 |

| Slight | 29 | 28.4 | |

| Moderate | 10 | 9.8 | |

| Intense | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Swelling the week after | No swelling | 86 | 84.3 |

| Slight | 14 | 13.7 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Calle Cañadas, C.; Martínez-Rodríguez, N.; Santos-Marino, J.; Martínez-González, J.M.; Barona-Dorado, C. The Influence of Anxiety on Postoperative Quality of Life Regarding Implant Treatments: An Epidemiological Study. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12060165

de la Calle Cañadas C, Martínez-Rodríguez N, Santos-Marino J, Martínez-González JM, Barona-Dorado C. The Influence of Anxiety on Postoperative Quality of Life Regarding Implant Treatments: An Epidemiological Study. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(6):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12060165

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Calle Cañadas, Carmen, Natalia Martínez-Rodríguez, Juan Santos-Marino, José María Martínez-González, and Cristina Barona-Dorado. 2024. "The Influence of Anxiety on Postoperative Quality of Life Regarding Implant Treatments: An Epidemiological Study" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 6: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12060165

APA Stylede la Calle Cañadas, C., Martínez-Rodríguez, N., Santos-Marino, J., Martínez-González, J. M., & Barona-Dorado, C. (2024). The Influence of Anxiety on Postoperative Quality of Life Regarding Implant Treatments: An Epidemiological Study. Dentistry Journal, 12(6), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12060165