Abstract

The aim of the study is to review the literature to observe studies that evaluate the extent of the thermal effect of different laser wavelengths on the histological evaluation of oral soft tissue biopsies. An electronic search for published studies was performed on the PubMed and Scopus databases between July 2020 and November 2022. After the selection process, all the included studies were subjected to quality assessment and data extraction processes. A total of 28 studies met the eligibility criteria. The most studied laser was the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, followed by the diode laser 940 nm–980 nm. Six studies were focused on each of the Erbium-doped Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (Er:YAG), Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers, and diode lasers of 808 nm and 445 nm. Three studies were for the Potassium Titanyl Phosphate (KTP) laser, and four studies were for the Erbium, Chromium-doped Yttrium, Scandium, Gallium, and Garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG) laser. The quality and bias assessment revealed that almost all the animal studies were at a low risk of bias (RoB) in the considered domains of the used assessment tool except the allocation concealment domain in the selection bias and the blinding domain in the performance bias, where these domains were awarded an unclear or high score in almost all the included animal studies. For clinical studies, the range of the total RoB score in the comparative studies was 14 to 23, while in the non-comparative studies, it was 11 to 15. Almost all the studies concluded that the thermal effect of different laser wavelengths did not hinder the histological diagnosis. This literature review showed some observations. The thermal effect occurred with different wavelengths and parameters and what should be done is to minimize it by better adjusting the laser parameters. The extension of margins during the collection of laser oral biopsies and the use of laser only in non-suspicious lesions are recommended because of the difficulty of the histopathologist to assess the extension and grade of dysplasia at the surgical margins. The comparison of the thermal effect between different studies was impossible due to the presence of methodological heterogeneity.

1. Introduction

The oral biopsy is considered the diagnostic gold standard of oral soft tissue lesions, due to its ability to analyze lesions at the histopathological levels [1]. Several surgical cutting instruments can be used to perform oral biopsies such as a scalpel, electrosurgery, and lasers [2].

Lasers have been extendedly used in oral surgery throughout the past 30 years as an incision tool. Nowadays more than ten different laser devices are available for dental use [3]. They can be classified according to wavelengths, active medium, power, or the produced biological effects [4]. Enhancements and improvements to the clinical and surgical procedures have been reported with laser use when compared with the cold blade, including the high degree of decontamination of the surgical site, the minimal postoperative bleeding, and the significant reduction of inflammation and postoperative pain [5].

The interaction between the laser beam and the target tissue is the fundamental consideration for the clinical use and selection of laser devices. Each laser wavelength has an affinity to specific human tissue chromophores which can absorb specific radiations in the visible and invisible portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. These chromophores are melanin, water, hemoglobin, and hydroxyapatite.

The laser soft tissue cutting effect is based on the photothermal effect of laser, where the laser interacts with specific tissue chromophores leading to the heating and vaporization of the targeted tissues, and eventually the tissue dissection. This mechanism of action leads to a thermal effect at the margins of specimens [4,5].

Since safe and readable margins of collected samples, in particular of suspicious dysplastic or neoplastic lesions, are extremely important, several studies have been conducted with different lasers and parameters to evaluate the extent of the thermal effect and its influence on the histological evaluation and interpretation, in order to achieve a standardized protocol exploiting the maximum benefits and the minimal drawbacks of the laser as an incision tool [3,5,6].

To our knowledge, the literature might have not been reviewed systematically to observe studies investigating this issue. The aim of the study is to review the literature to observe studies assessing the thermal effect with different laser wavelengths on the histological evaluation of oral soft tissue biopsies and to analyze the difference in the resulting thermal effects in soft tissue specimens collected by different wavelengths and parameters. The laser wavelengths considered in this review are the Potassium Titanyl Phosphate (KTP) laser of 532 nm; diode lasers of 445 nm, 808 nm, and 940 nm–980 nm; Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (Nd:YAG) laser of 1064 nm; Erbium, Chromium-doped Yttrium, Scandium, Gallium and Garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG) laser of 2780 nm; Erbium-doped Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (Er:YAG) laser of 2940 nm; and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted following the parameters of PRISMA, “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses”, guidelines.

The focus question was: “what is the impact of the thermal effect of different laser wavelengths on the histological evaluation of laser-collected oral biopsy?”.

The systematic review was registered at PROSPERO, “the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews”, with registration nr. CRD42022385059.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria of the studies on this systematic review were studies that evaluated the thermal effect of lasers on soft tissue biopsies specimens, reporting the measurements of the thermal effect histologically, utilizing one of the following wavelengths or all of them: 532 nm KTP; diode lasers of 445 nm, 808 nm, and 980 nm; 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser; 2780 nm Er,Cr:YSGG laser; 2940 nm Er:YAG laser; and CO2 laser. All the studies had to be written in the English language. Almost all kinds of studies were considered: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), clinical trials, and animal (in vivo or ex vivo) studies.

Studies with incomplete experimental data, reviews (narrative and/or systematic), case reports, abstracts, and letters to editors were excluded from this review.

2.2. Search Strategy

The PubMed and Scopus databases were searched between July 2020 and November 2022. All MeSH terms, keywords, and terms related to laser, oral, biopsy, thermal, and effect were used and combined with Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” (Table 1). A manual search was also performed on the citation and reference lists of the included studies to identify other publications not recalled in the initial databases search.

Table 1.

Shows the used search strategy in the PubMed and Scopus databases.

2.3. Study Selection

The studies collected from the database search were screened independently in two stages by two reviewers (A.M. and A.N.). An independent screening of the titles and abstracts of the resulting studies was performed in the first stage based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the second stage, a full-text read of the selected studies was performed to confirm the suitability of the articles for the review. An arbitration and discussion with a third reviewer (G.T.) were conducted in case of disagreements between the two reviewers at both stages.

2.4. Extraction and Synthesis of Data

The collection and synthesis of data were performed from each selected eligible study by the same two reviewers. The extracted data were: the author/year, study type (animal or clinical), laser wavelength, specimen type (including the clinical and histopathological perspectives), number of specimens (only specimens collected on oral soft tissues by the considered laser wavelengths in this revision), employed microscope, magnification power, method of histological evaluation, number of pathologists, main outcomes, and conclusions. In addition, the reported thermal effects were extracted from each study. The laser parameters were also collected including the wavelength (nm), type of emitter, groups (if present), number of samples (n) for each group and for each wavelength if present, frequency (Hz), energy (mJ), air/water ratio, fiber/spot diameter (μm), fluence (J/cm2), irradiance (W/cm2), and power (W). Conversion of units was performed for laser parameters and thermal effects if needed in order to have a better homogeneousness of the presented data.

The resulting data for all the included studies were synthesized tabularly and divided into (A) data that demonstrate the general overview of the sample distribution and evaluation details, and (B) data that demonstrate the laser parameters and the resulting thermal effects. At this stage, the third reviewer (G.T.) was consulted in case of any disagreements between the two reviewers (A.M. and A.N.).

Heterogeneousness of the data was observed among the included studies concerning the study design, laser parameters, sample type, histological evaluation methods, and reported thermal effect that hindered the authors from carrying out the meta-analysis. Therefore, only a narrative review and tabular synthesis of data were performed.

2.5. Assessment of Quality and Bias

For the assessment of the quality and risk of bias (RoB) of the included studies, different assessment tools were employed according to the type of the studies. In animal studies, SYRCLE’s (“Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation”) tool was used [7]. This tool consists of six types of bias with 10 domains. Each domain is scored with low, unclear, or high risk.

In clinical studies, the MINORS (“Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies”) tool was used [8]. This quality assessment tool consists of 12 methodological items. The first eight items can be applied to both comparative and non-comparative studies, while the remaining four items are applied only to comparative studies. The scores are “0” for not reported, “1” for reported but inadequate, or “2” for reported and adequate. At the end of the assessment, the total score should be calculated where the ideal score would be 16 for non-comparative studies and 24 for comparative studies.

3. Results

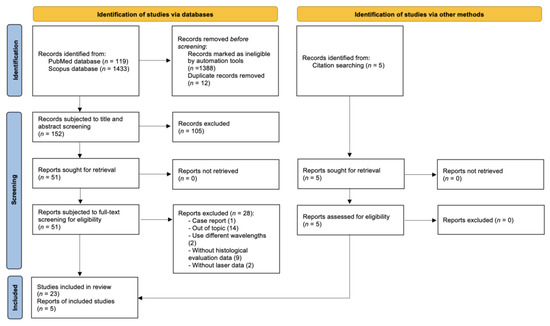

The initial search on the PubMed database resulted in a total of 119 studies in the time period between 1987 and 2022. On the Scopus database, 1433 studies were identified in the time period between 1990 and 2022. After the removal of duplicates and the removal of studies by the automated tools, a total of 152 studies were subjected to the title and abstract screening. After the second stage of the screening (full-text read), a total of 23 studies met the eligibility criteria. Another 5 studies were identified from the reference and citation lists. A total of 28 studies were included in this review and subjected to the extraction of data and quality assessment (Figure 1) [9].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram shows the study selection process.

The exclusion of the 28 studies was due to different reasons, including studies that use different wavelengths than considered ones, studies that use only qualitative methods for the description of thermal effects, studies with incomplete experimental data, and/or studies with an incomplete report of important parameters.

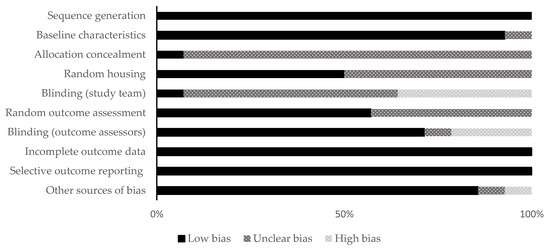

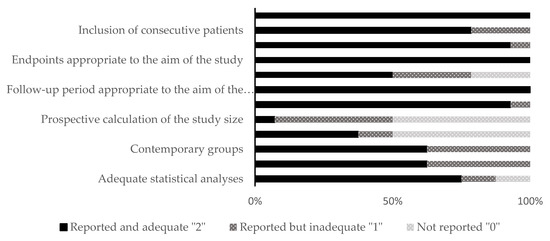

The included studies were distributed as follows: fourteen animal studies and 14 clinical studies. The qualitative analysis was performed for all the included studies using different RoB assessment tools (SYRCLE and MINORS) according to the kind of study. The allocation concealment domain in the selection bias and the blinding domain in the performance bias were awarded unclear or high in almost all the included animal studies. For clinical studies, there were six non-comparative studies and eight comparative studies. The range of the total RoB score in the comparative studies was 14 to 23, while in the non-comparative studies, it was 11 to 15. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the scores of different considered domains of the used RoB assessment tools of all the included studies.

Figure 2.

Quality and risk of bias assessment scores of the animal studies using the SYRCLE’s tool.

Figure 3.

Quality and risk of bias assessment scores of clinical studies (in vivo) using the MINORS tool.

3.1. Animal Studies

A total of 607 samples were collected in the animal studies for the histological evaluation of the thermal effect of lasers. Table 2 shows an overview and evaluation details of all included animal studies. The samples were harvested from pig tongue [5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], bovine tongue [17], pig oral mucosa [18], rabbit ventral surface of the tongue [19], Sprague rat tongue [20], and porcine oral mucosa and gingiva [3,21]. The examined wavelengths were distributed among the animal studies as follows: 808 nm laser in three studies [10,17,21], 940 nm–980 nm laser in five studies [10,13,15,16,18], 445 nm laser in three studies [14,17,18], Nd:YAG laser in four studies [10,13,17,21], Er,Cr:YSGG laser in four studies [3,10,19,21], KTP laser in two studies [11,17], Er:YAG laser in three studies [12,13,21], and CO2 laser in five studies [3,5,13,20,21].

Table 2.

Overview and evaluation details of all included animal studies.

The histological evaluation was conducted in all the included animal studies by optical microscopes with a magnification range ranging from 10× to 40×. In six studies, the histological evaluation was made by two pathologists, while in five studies it was made by only one pathologist. Moreover, this issue was not clearly declared in the other three studies.

Different methods were considered for the evaluation of the thermal effects of lasers. Only qualitative evaluations were carried out in five studies [10,11,12,17,19]. Rizoiu et al. [19] and Romeo et al. [10] based their evaluation on identifying the artefactual changes, the marginal coagulation zones of hyalinization, and the degree of inflammation. In two studies by Romeo et al. [11,12], the evaluation of specimens was through identifying the Thermal Damage Score (TDS) that consists of a scale of four items from 0 to 3 (0 “no damage”, 1 “little damage”, 2 “moderate damage”, and 3 “severe damage”), while Fornaini et al. [17] evaluated the cut quality by assigning a score to the specimens from 0 to 5, where 5 was the highest quality with the cold blade.

The other nine studies performed both qualitative and quantitative evaluations of the specimens [3,5,13,14,15,16,18,20,21]. Palaia et al. [5,14,15] in their studies evaluated the specimens identifying the TDS and determining the width of peripheral thermal effects. Azevedo et al. [13] evaluated the specimens macroscopically based on the criteria of Cercadillo-Ibarguren (a scale of 0 to 4) and histologically through identifying the epithelial, Connective Tissue (CT), vascular changes, incision morphology, and the overall width of tissue modifications [3]. Braun et al. [18] measured the Maximum Denaturation Depth (MDD) and Denaturation Area (DA) for all the included specimens. Kawamura et al. [21] made the histological and histometric analysis of the coagulated and thermally affected layers at the ablation bottom. Cercadillo-Ibarguren et al. [3] performed macroscopic and histological evaluation through the measurement of the extension of the hyalinized or coagulated tissue adjacent to the irradiation edge. Seoane et al. [20] evaluated histologically the epithelial features, the number of artefacts, and the width of thermal damage. Prado et al. [16] calculated histologically the Thermal Damage Depth (TDD) and the Thermal Damage Area (TDA), where they calculated the TDA by calculating the difference between the total area of each specimen and its total area of thermal damage.

3.2. Clinical Studies

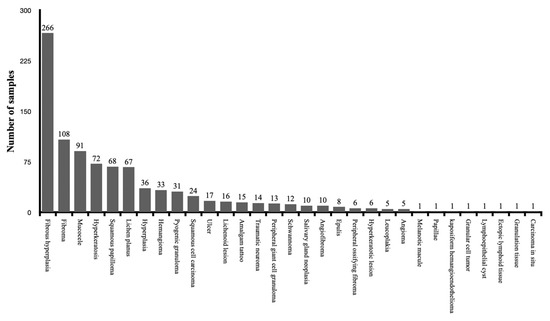

A total of 1117 specimens were collected in the clinical studies and the evaluation of the thermal effect of the used lasers was performed. All the specimens were collected for the diagnosis of oral soft tissue lesions. The histopathological diagnosis was reported for a total of 941 specimens, while 176 specimens were not clearly identified in four clinical studies. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the specimens according to the diagnosis of lesions. The overview and evaluation details of all included clinical studies are resumed in Table 3.

Figure 4.

The distribution of the specimens according to the diagnosis of lesions among the clinical studies.

Table 3.

Overview and evaluation details of all included clinical studies.

In three studies, the specimens were limited to fibrous hyperplasia lesions [22,23,24]. In five studies, the localization of the oral soft tissue lesions was considered as an inclusion criterion. It was the tongue in one study [25], the buccal mucosa in three studies [22,23,24], and both cheek and buccal mucosa in one study [26]. There were six non-comparative studies [22,27,28,29,30,31], and eight comparative studies [23,24,25,26,32,33,34,35]. Among the included studies, there were two retrospective studies [28,34] and two RCTs [22,24].

The distribution of the examined wavelengths among the clinical studies was the following: 808 nm in three studies [28,32,35], 980 nm in three studies [33,34,35], 445 nm in three studies [30,31,33], Nd:YAG laser in two studies [26,34], KTP laser in one study [32], Er:YAG laser in three studies [23,24,34], and CO2 laser in seven studies [22,23,24,25,27,29,34].

In the clinical studies, the optical microscope was mentioned in the methods for the histological evaluation in all the studies except for four studies [22,23,24,33]. The magnification range was from 5× to 100×. One pathologist was responsible for the histological evaluation in ten studies [22,23,24,26,29,30,31,32,33,34], and two pathologists in two studies [28,35]. In two studies, the number of examiners was not precise [25,27].

The thermal effect of the examined wavelengths was evaluated qualitatively and quantitively in all the clinical studies by different methods. The epithelial, CT, vascular changes, incision morphology, and overall width of tissue modifications were considered in three studies [26,28,34]. In three studies by Suter et al. [22,23,24] and a study by Gill et al. [35], the maximum, minimum, mean, and median values of the Thermal Damage Zone (TDZ) were measured. Matsumoto et al. [25] measured the distances from the edges of the specimen to the thermal artifacts. In four studies, the thermal effect at the peri-incisional margins was measured quantitively for both the epithelium and CT [29,30,31,32]. In one study, the tissue necrosis width was measured for five different soft tissues (epithelium, connective tissue “loose and dense”, muscle, and salivary gland epithelium) [27]. Gobbo et al. [33] quantified the maximum thermal damage along the cutting margin.

3.3. Laser Parameters

There was a difference in the examined parameters for each considered laser system. Among the considered wavelengths, the most evaluated laser system for the thermal effect on soft tissues was the CO2 laser followed by the diode lasers 940 nm–980 nm. The least evaluated was the KTP laser in only three studies [11,17,32]. The examined laser parameters of all the included studies were summarized in Table 4 and distributed according to the wavelength and accompanied by the reported thermal effect.

Table 4.

Overview of laser parameters and the resulted thermal effects of the included studies.

4. Discussion

Despite the differences and heterogeneity among the included studies, almost all of them showed that the different tested laser wavelengths did not have a thermal effect that may hinder the histological diagnosis. It appears that the use of laser in oral biopsy should be tailored by managing variables related to the extent of histological thermal effects, including the histological condition of the target tissue (healthy or pathological), the size of the excised lesion, the operator experience, and the source of energy emission, to minimize the thermal effect that cannot be prevented.

Concerning the 808 nm laser, six studies (three clinical and three animal studies) evaluated the thermal effect on soft tissues [10,17,21,28,32,35]. The range of the tested powers was 1 to 3 W. The fluence was reported in two studies and ranged from 284 to 2400 J/cm2 [10,32]. The irradiance was reported only in two studies with a range of 1415.4 to 2400 W/cm2 [10,21]. The spot size was 320 µm in all the studies except for one study in which it was 300 µm [21]. The laser was tested in Continuous Wave (CW) mode in all the studies except for one study where it was tested in Pulsed Wave (PW) with a Ton of 100 ms and Toff of 100 ms [10]. The range of the reported thermal effect in clinical studies with almost similar parameters was 17.92 to 473 µm [28,32]. All the studies suggested that the 808 nm laser can be considered an affordable tool and confirm the possibility of having a clear histological diagnosis. However, the extension of margins during the excision of oral lesions was also recommended [10,32]. In one study, it was recommended to use this laser on oral lesions with a diameter of more than 3 mm because they found that specimens under 3 mm had frequently significant epithelial, stromal, and/or vascular changes and the diagnosis in 46.15% of these specimens was not achievable [28].

Among the eight studies of diode laser 940–980 nm, five studies (two animal and three clinical) reported the extent of the thermal effect with a range of 100 to 1198.54 µm [13,15,33,34,35]. Two of them tested the power of 3.5 W in PW and one at 2 W in PW. In one study, the MDD and the DA were evaluated with a power of 3 W in CW and PW, where the mean MDD was 208 μm in CW and 124 μm in PW, and the mean DA was 127 μm in CW and 307 μm in PW [18]. Among the eight studies, three studies reported fluence. The range of the tested fluence was 99.2 to 4777 J/cm2. The irradiance was reported in three studies and ranged from 1415.4 to 4957.5 W/cm2. The range of tested powers was 1 to 6 W. The reported spot size was 320 μm in three studies, 300 μm in two studies, 400 μm in one study, and not mentioned in two studies. All the studies stated that diode laser 940–980 nm laser did not hinder the histological evaluation, and two studies recommended the use of laser in pulsed mode with the extension of margins [10,18].

Concerning the 445 nm laser (Blue laser), all the included six studies (three animal and three clinical) reported the best quality of cut and minimal thermal effect in comparison with others [14,17,18,31,33,35]. In three studies (one animal and two clinical), the extent of thermal effect was reported for the epithelium and CT [14,30,31]. The mean extent of the thermal effect with almost the same parameters was evidently higher on the epithelium in the clinical study than that in the animal study, whereas the mean extent of thermal effect on the epithelium, with approximately 2 W in CW, was 137.5 μm in the animal study, and 650.93 μm in the clinical study, while for the CT, the mean extent of thermal effect with the same abovementioned parameters was approximately similar between the clinical and animal studies [14,30,31]. All the studies on the 445 nm laser used a fiber of 320 μm and tested the range of power from 1.4 to 4 W. Only two studies reported fluence (3100 J/cm2) [30,31].

Six included studies (four animal and two clinical studies) evaluated histologically the thermal effect of the Nd:YAG laser on the excision of soft tissue lesions [10,13,17,21,26,34]. All of them tested the laser in PW. The fiber size was 300 μm in three studies [13,21,34], 320 μm in two studies [17,26], and 400 μm in one study [10]. The range of tested powers was from 1 to 6 W. The fluence was reported in three studies with a range of 95.5 to 141.6 J/cm2 [10,21,34], and the irradiance was reported in three studies with a range of 300 to 5665.7 W/cm2 [4,6,23]. The total extent of the thermal effect was measured in four studies [13,21,26,34]. Among them, two clinical studies evaluated the thermal effect on the epithelium and CT [13,34]. The thermal effect on CT was quite similar in both studies when comparing the results of approximately similar parameters (3.5 W in PW and 4 W in PW), where it was 376.6 μm and 310.85 μm, respectively, while the thermal effect on epithelium was clearly different between the two studies with these above-mentioned parameters, where it was 305.8 μm and 899.83 μm, respectively [13,34]. In all the included studies, the extent of the thermal effect with Nd:YAG was the highest when compared to other lasers and, in one clinical study by Vescovi et al., serious thermal effects were observed in small specimens (less than 7 mm) independently from the settings employed [26].

Er,Cr:YSGG laser was tested in four animal studies [3,10,19,21]. The spot size was 600 μm in three studies and 680 μm in one study. The irradiance was reported only in one study with a range of 707 to 1000 W/cm2 and the fluence was reported in two studies with a range of 35 to 53 J/cm2 [10,21]. The reported extent of thermal effect was quite small with all tested powers in particular with the use of air/water spray. In two studies with similar parameters, the range of total extent of thermal effect was 9.26 to 33.1 μm. The parameters were a power of 1 W in PW (20 Hz) with air/water spray and a spot diameter of 600 μm [3,21].

All the studies that tested the KTP laser demonstrated a low thermal effect on soft tissues [11,17,32]. The range of tested powers was 1.5 to 3 W. Only one clinical study reported the extent of the thermal effect with a range of 196 to 213 μm with a power of 1.5 W in PW and a fiber diameter of 300 μm [32].

Er:YAG laser was tested in six studies (three animal and three clinical studies) and almost all of them showed that it is a conservative tool [12,13,21,23,24,34]. All the included studies tested the Er:YAG laser in PW mode. The range of tested powers was 1 to 7 W. In two animal studies, Er:YAG laser was tested with and without air/water spray in PW with different powers [13,21]. Both studies demonstrated a lower thermal effect with the use of air/water spray. In all the studies that compared the Er:YAG laser with other laser systems, the Er:YAG laser showed the least thermal effect [13,21,23,24,34].

The CO2 laser was the most studied laser: it was tested in twelve studies (five animal and seven clinical studies) [3,5,13,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,29,34]. The range of tested powers was 1 to 20 W. The fluence was reported in only one study (40.8 J/cm2) [34]. The irradiance was reported in three studies (796.2, 2040.8, and 2320 W/cm2) [21,27,34]. All the studies confirmed that it is a reliable tool for the excision of soft tissues. CO2 laser showed the lowest thermal effect when tested in studies that compare it with other laser systems except for Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers [3,13,21,23,24,34]. In one study, the authors reported produced epithelial damage for both low- and high-tested powers (3 W to 12 W) similar to light dysplasia features that could cause erroneous therapy. Interestingly, the lowest measured thermal effect was observed in this study in the group of high power (12 W) [20].

From this revision, some observations must be highlighted. First, the reported thermal effects were slightly different among animal studies and clinical studies, which is predictable because animal studies were usually done in ex vivo conditions, where the specimens were deprived of blood when compared to clinical conditions mainly for wavelengths highly absorbed by Haemoglobin (Hb). Second, even similar studies showed differences in the extent of the thermal effect that may be influenced by the difference in effects on pathologic tissue depending on the lesion characteristics. Third, although almost all the studies conclude that the thermal effect of different laser wavelengths does not hinder the histological diagnosis and evaluation, thermal damage occurs and what should be considered is to minimize the thermal effect by better adjusting laser parameters.

Finally, there were some limitations that need to be highlighted. First, the meta-analysis and comparison among the included studies were not applicable due to the diversity in the methodological approaches regarding the histometric analysis, laser parameters, and sample types. Second, a selection bias should be considered, as this systematic approach depended only on papers in the English language, and that were recruited by research on PubMed and Scopus databases. Third, some studies reported the extent of the thermal effect of the tested laser in a confusing way that hindered the comparison process. For future studies, it should be more advisable to include the micrometric measurements of both epithelial and CT thermal effects.

5. Conclusions

From this literature review, there emerged some observations. Some studies recommended the extension of margins during the collection of laser oral biopsies and some of them recommended the use of laser only in non-suspicious lesions because of the possible difficulty of the histopathologist to assess the extension and grade of dysplasia at the surgical margins. The comparison of the thermal effect between different studies was impossible due to the presence of methodological heterogeneity. Further studies are needed with a standardized approach with micrometric measurements of epithelial and connective tissue thermal effects for comparative purposes and eventually determining a standard approach and parameters for the use of each type of laser on oral biopsies, in particular because there are many reported advantages to using lasers that may eventually improve patients’ management, such as the lesser use of local anaesthesia, the anti-inflammatory effect, and the possibility to have a bloodless operation field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T., A.M., A.N., F.R., A.D.V., G.P., C.R.T.D.G., A.C. and U.R.; methodology, G.T., A.M., A.N., F.R., A.D.V., A.C. and U.R.; software, G.T., A.M. and A.N.; validation, G.T., A.M. and A.N.; formal analysis G.T., A.M., F.R. and A.N.; investigation, G.T., A.M. and A.N.; resources, G.T., A.M., and A.N.; data curation, G.T., A.M., F.R., C.R.T.D.G. and U.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.T., A.M. and A.N.; writing—review and editing, G.T., A.M., A.N., F.R., A.D.V., G.P., C.R.T.D.G., A.C. and U.R.; visualization, G.T., A.M. and A.N.; supervision, G.T., A.D.V., G.P., C.R.T.D.G., A.C. and U.R.; project administration, G.T., A.D.V., G.P., C.R.T.D.G., A.C. and U.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saini, R.; Saini, S.; Sharma, S. Oral biopsy: A dental gawk. J. Surg. Tech. Case Rep. 2010, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avon, S.L.; Klieb, H.B. Oral soft-tissue biopsy: An overview. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 78, c75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cercadillo-Ibarguren, I.; España-Tost, A.; Arnabat-Domínguez, J.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Histologic evaluation of thermal damage produced on soft tissues by CO2, Er,Cr:YSGG and diode lasers. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2010, 15, e912–e918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, R.M.; Colvard, M.D. Current status of lasers in soft tissue dental surgery. J. Periodontol. 1993, 64, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; Impellizzeri, A.; Tenore, G.; Visca, P.; Libotte, F.; Russo, C.; Romeo, U. Histological ex vivo evaluation of peri-incisional thermal effect created by a new-generation CO2 superpulsed laser. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 345685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convissar, R.A. Laser biopsy artifact. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1997, 84, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, U.; Del Vecchio, A.; Ripari, F.; Palaia, G.; Chiappafreddo, C.; Tenore, G.; Visca, P. Effects of different laser devices on oral soft tissue: In vitro experience. J. Oral. Laser Appl. 2007, 7, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, U.; Palaia, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; Tenore, G.; Gambarini, G.; Gutknecht, N.; De Luca, M. Effects of KTP laser on oral soft tissues. An in vitro study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, U.; Libotte, F.; Palaia, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; Tenore, G.; Visca, P.; Nammour, S.; Polimeni, A. Histological in vitro evaluation of the effects of Er:YAG laser on oral soft tissues. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, A.S.; Monteiro, L.S.; Ferreira, F.; Delgado, M.L.; Garcês, F.; Carreira, S.; Martins, M.; Suarez-Quintanilla, J. In vitro histological evaluation of the surgical margins made by different laser wavelengths in tongue tissues. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, e388–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaia, G.; Impellizzeri, A.; Tenore, G.; Caporali, F.; Visca, P.; Del Vecchio, A.; Galluccio, G.; Polimeni, A.; Romeo, U. Ex vivo histological analysis of the thermal effects created by a 445-nm diode laser in oral soft tissue biopsy. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 2645–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, G.; Renzi, F.; Pergolini, D.; Del Vecchio, A.; Visca, P.; Tenore, G.; Romeo, U. Histological Ex Vivo Evaluation of the Suitability of a 976 nm Diode Laser in Oral Soft Tissue Biopsies. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 6658268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, M.C.O.; Nwizu, N.N.; Patel, S.A.; Streckfus, C.F.; Zezell, D.M.; Barros, J. Thermal damage and excision time of micro and super pulsed diode lasers: A comparative ex vivo analysis. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaini, C.; Merigo, E.; Rocca, J.P.; Lagori, G.; Raybaud, H.; Selleri, S.; Cucinotta, A. 450 nm Blue Laser and Oral Surgery: Preliminary ex vivo Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2016, 17, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.; Kettner, M.; Berthold, M.; Wenzler, J.S.; Heymann, P.G.B.; Frankenberger, R. Efficiency of soft tissue incision with a novel 445-nm semiconductor laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizoiu, I.M.; Eversole, L.R.; Kimmel, A.I. Effects of an erbium, chromium: Yttrium, scandium, gallium, garnet laser on mucocutanous soft tissues. Oral Surg Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1996, 82, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, J.; Caballero, T.G.; Urizar, J.M.; Almagro, M.; Mosquera, A.G.; Varela-Centelles, P. Pseudodysplastic epithelial artefacts associated with oral mucosa CO2 laser excision: An assessment of margin status. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 39, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, R.; Mizutani, K.; Lin, T.; Kakizaki, S.; Mimata, A.; Watanabe, K.; Saito, N.; Meinzer, W.; Iwata, T.; Izumi, Y.; et al. Ex Vivo Evaluation of Gingival Ablation with Various Laser Systems and Electroscalpel. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, V.G.; Altermatt, H.J.; Dietrich, T.; Reichart, P.A.; Bornstein, M.M. Does a pulsed mode offer advantages over a continuous wave mode for excisional biopsies performed using a carbon dioxide laser? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, V.G.A.; Altermatt, H.J.; Bornstein, M.M. A randomized controlled clinical and histopathological trial comparing excisional biopsies of oral fibrous hyperplasias using CO2 and Er:YAG laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, V.G.A.; Altermatt, H.J.; Bornstein, M.M. A randomized controlled trial comparing surgical excisional biopsies using CO2 laser, Er:YAG laser and scalpel. Int. J Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Suzuki, H.; Usami, Y.; Hattori, M.; Komoro, T. Histological evaluation of artifacts in tongue tissue produced by the CO2 laser and the electrotome. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2008, 26, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vescovi, P.; Corcione, L.; Meleti, M.; Merigo, E.; Fornaini, C.; Manfredi, M.; Bonanini, M.; Govoni, P.; Rocca, J.P.; Nammour, S. Nd:YAG laser versus traditional scalpel. A preliminary histological analysis of specimens from the human oral mucosa. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrel, M.A.; McCracken, K.J.; Daniels, T.E. Histologic evaluation of the width of soft tissue necrosis adjacent to carbon dioxide laser incisions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1990, 70, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiero, F.; Parma, L.; Crippa, R.; Benedicenti, S. Diode laser (808 nm) applied to oral soft tissue lesions: A retrospective study to assess histopathological diagnosis and evaluate physical damage. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenore, G.; Palaia, G.; Mohsen, A.; Ambrogiano, S.; Gioia, C.R.T.D.; Dominiak, M.; Romeo, U. Could the super-pulsed CO2 laser be used for oral excisional biopsies? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 28, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, G.; Pergolini, D.; D’Alessandro, L.; Carletti, R.; Del Vecchio, A.; Tenore, G.; Di Gioia, C.R.T.; Romeo, U. Histological Effects of an Innovative 445 Nm Blue Laser During Oral Soft Tissue Biopsy. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, G.; D’Alessandro, L.; Pergolini, D.; Carletti, R.; Di Gioia, C.R.T.; Romeo, U. In vivo clinical and histological thermal effect of a 445 nm diode laser on oral soft tissues during a biopsy. J. Oral. Sci. 2021, 63, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, U.; Russo, C.; Palaia, G.; Lo Giudice, R.; Del Vecchio, A.; Visca, P.; Migliau, G.; De Biase, A. Biopsy of different oral soft tissues lesions by KTP and diode laser: Histological evaluation. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 761704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbo, M.; Bussani, R.; Perinetti, G.; Rupel, K.; Bevilaqua, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Biasotto, M. Blue diode laser versus traditional infrared diode laser and quantic molecular resonance scalpel: Clinical and histological findings after excisional biopsy of benign oral lesions. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 121602, Erratum in J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, L.; Delgado, M.L.; Garcês, F.; Machado, M.; Ferreira, F.; Martins, M.; Salazar, F.; Pacheco, J.J. A histological evaluation of the surgical margins from human oral fibrous-epithelial lesions excised with CO2 laser, Diode laser, Er:YAG laser, Nd:YAG laser, electrosurgical scalpel and cold scalpel. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e271–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.; Sandhu, S.V.; Sethi, N.; Bhandari, R. Biopsy of oral soft tissue lesions by 808 nm and 980 nm diode laser: A morphological and histochemical evaluation. Laser Dent. Sci. 2021, 5, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).