Maximizing Student Clinical Communication Skills in Dental Education—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Special Characteristics about the Dental Clinic and Communication

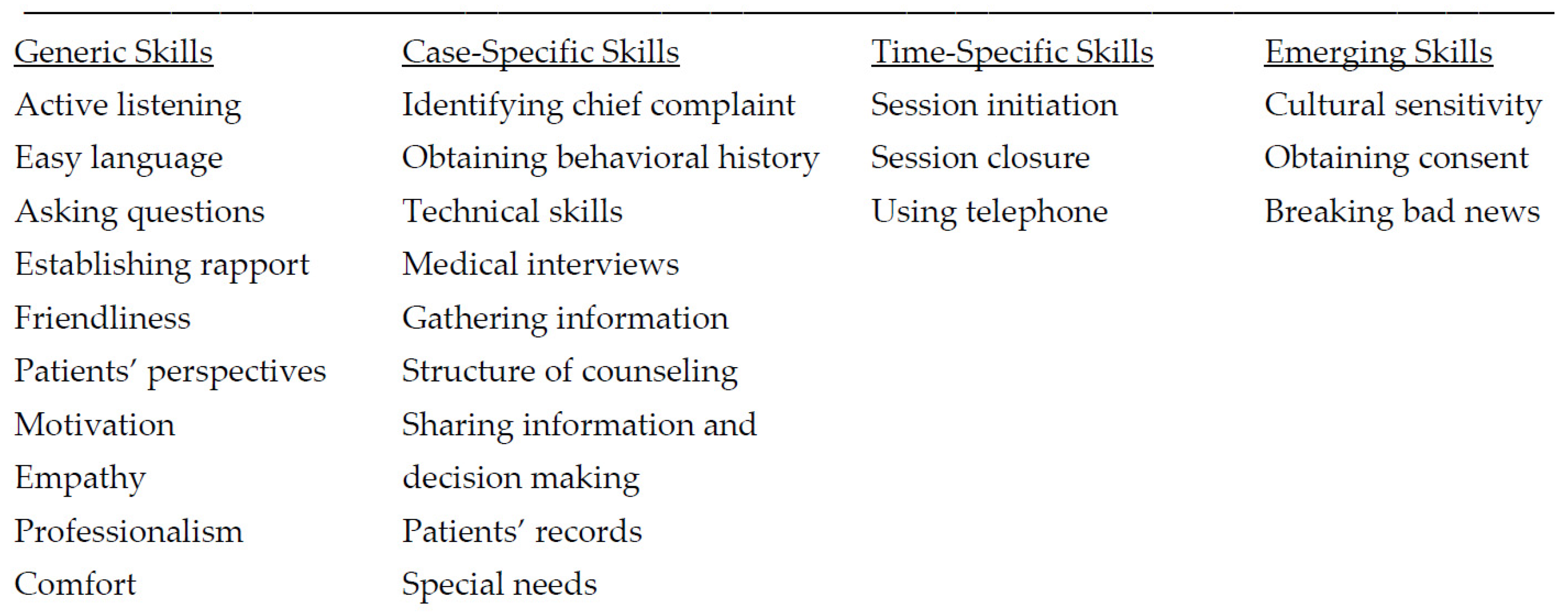

4.2. Essential Components of Dental Student Learning of Communication Skills

Patient-Centered Care—Active Listening and Empathy

4.3. Other Essential Aspects of Education of Dental Students in Communication Skills

4.3.1. Role-Play vs. Clinical Video Projects

4.3.2. The Role of Clinical Instructors in Communication Skills Learning

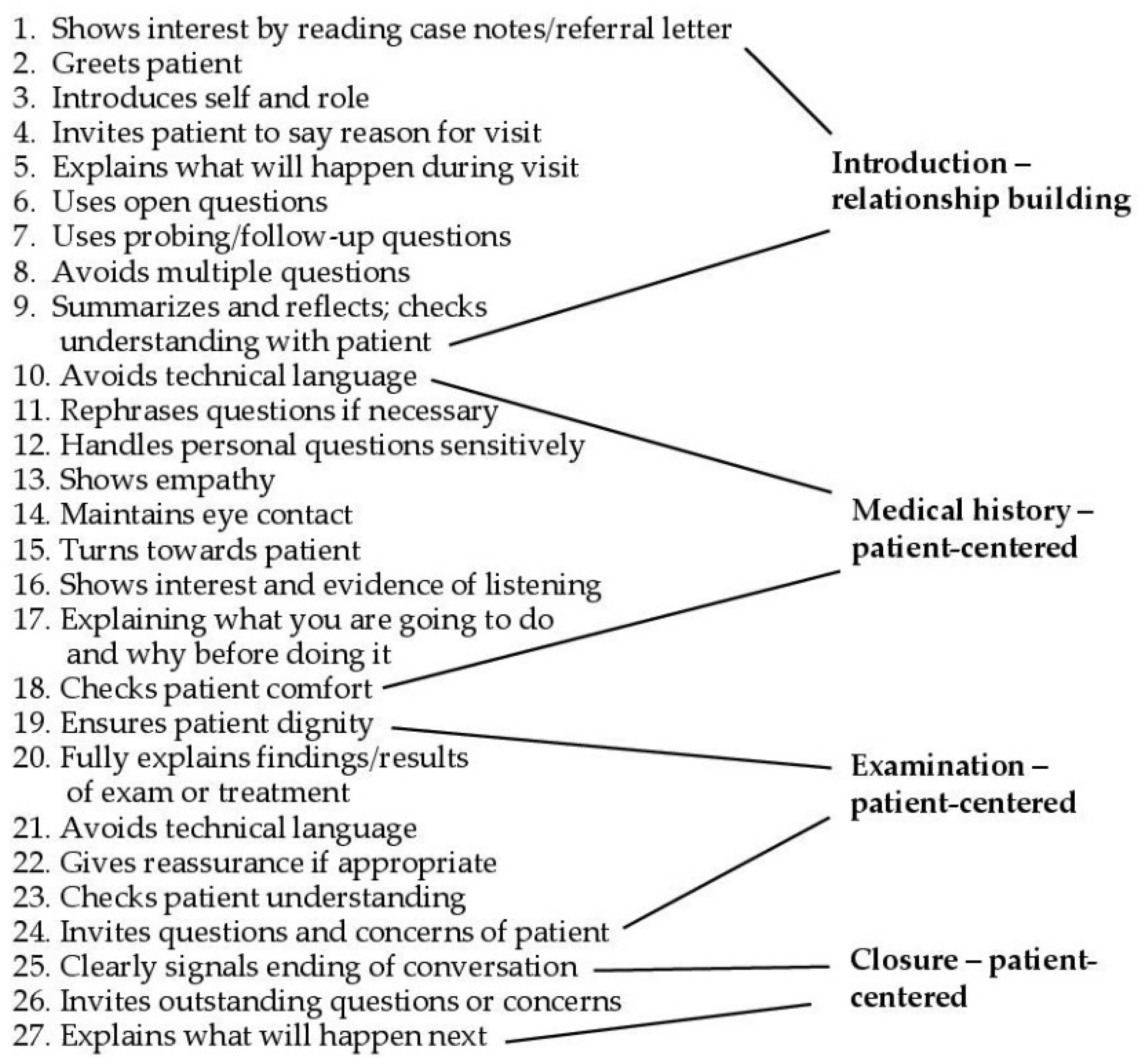

4.4. Clinical Consultation Guides and Styles Used in Communication Skills Learning

4.4.1. Motivational Interviewing Consultation Style

- Open-ended questioning—In contrast to closed questions, which generally require a simple yes/no or numeric answer, open questions do not direct a patient to respond in a particular manner. Instead, they enable a patient to think through and provide richer, fuller responses. The conversation should be started with words such as how or what or describe so that the patient does most of the talking.

- Affirmations—Sincere affirmations can help build a stronger relationship with a patient. These are the statements and gestures of health care workers that help the patient to recognize strength and acknowledge behaviors that lead to positive change, regardless of how big or small.

- Reflective listening—Akin to active listening, this demonstrates that the clinician has accurately heard and understood a patient’s communication. This relational empathy encourages further exploration of problems and feelings and encourages “change talk”.

- Summaries reinforce what has been said. Summary statements include trying to obtain the full picture of a patient’s behavior and checking with the patient to make sure that they feel the health care professional has reflected their situation accurately. Summarizing helps in integrating the communication that has occurred between the patient and provider.

4.4.2. Macy Model of Doctor–Patient Communication

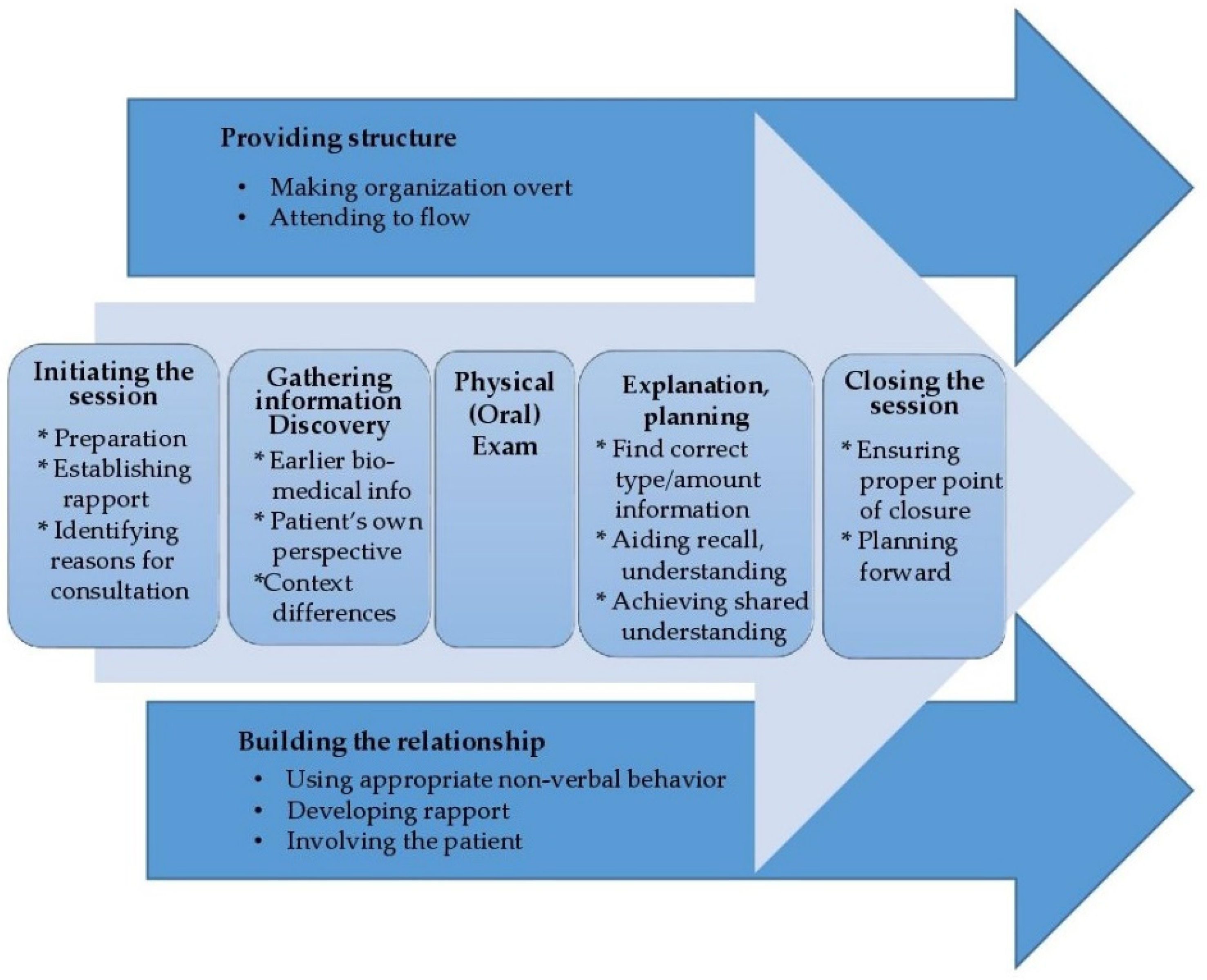

4.4.3. Calgary–Cambridge Guide (C-CG) to Health Consultations

4.4.4. The “Four Habits” Model Plus One Extra Good Dentist Habit

4.5. Optimal Curricular Structure for Clinical Communication Learning Effectiveness

Longitudinal vs. One-Time Learning

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.B.; Boles, M.; Mullooly, J.P.; Levinson, W. Effect of Clinician Communication Skills Training on Patient Satisfaction. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 131, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkhof, M.; Van Rijssen, H.J.; Schellart, A.J.M.; Anema, J.R.; Van Der Beek, A.J. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: An overview of systematic reviews. Pat. Educ. Counsel. 2011, 84, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelber, J.P.; Deimling, D.; Langenbach, D.; Ratka-Krüger, P. The importance of teaching communication in dental education. A survey amongst dentists, students and patients. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2012, 16, e200–e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R. Psychosocial Aspects of Dental Anxiety and Clinical Pain Phenomena. Ph.D. Thesis, Fællestrykkeriet for Sundhedsvidenskab, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, A.C.; Milgrom, P. Dentists’ attitudes toward frustrating patient visits: Relationship to satisfaction and malpractice complaints. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1995, 23, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.A.; Roter, D.L.; Katz, N.R. Meta-Analysis of Correlates of Provider Behavior in Medical Encounters. Med. Care 1988, 26, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, J.A.; Madill, A.; Manogue, M. Communications skills in dental education: A systematic research review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifah, A.M.; Celenza, A. Teaching and Assessment of Dentist-Patient Communication Skills: A Systematic Review to Identify Best-Evidence Methods. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, I.; Frost, J.; Cooper, C.; Moles, D.R.; Kay, E. Patient-centred care in general dental practice—A systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambler, S.; Delgado, M.; Asimakopoulou, K. Defining patient-centred care in dentistry? A systematic review of the dental literature. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Hoppe, R.B. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: A narrative review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondell, K.; Söderfeldt, B. Dentist—Patient Communication: A Review of Relevant Models. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1997, 55, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buduneli, N. Communication Skills of the Clinician and Patient Motivation in Dental Practice. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2020, 7, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lo, E.C.M.; Kot, S.C.C.; Chan, K.C.W. Motivational Interviewing in Improving Oral Health: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayn, C.; Robinson, L.; Nason, A.; Lovas, J. Determining Recommendations for Improvement of Communication Skills Training in Dental Education: A Scoping Review. J. Dent. Educ. 2017, 81, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüttermann, S.; Sobotta, A.; Hahn, P.; Kiessling, C.; Härtl, A. Teaching and assessment of communication skills in undergraduate dental education—A survey in German-speaking countries. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2017, 21, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Milgrom, P.; Coldwell, S. How do U.S. and Canadian dental schools teach interpersonal communication skills? J Dent. Educ. 2002, 66, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.; Burton, J. Aspects of control in the dentist-patient relationship. Int. J. Soc. Lang. 1985, 51, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

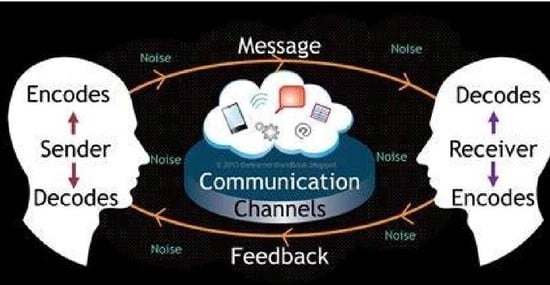

- Cheng, B.; Bridges, S.; Yiu, C.; McGrath, C. A review of communication models and frameworks in a healthcare context. Dent. Update 2015, 42, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torper, J.; Ansteinsson, V.; Lundeby, T. Moving the four habits model into dentistry. Development of a dental consultation model: Do dentists need an additional habit? Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 23, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.E.L. A study of the verbal behavior of family doctors. Int. J. Soc. Lang. 1985, 1985, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, W.S.Z.; Wolvin, A.D.; Chung, S. Students’ Self-Perceived Listening Competencies in the Basic Speech Communication Course. Int. J. Listening 2000, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottel, T.L.; Hardigan, P.C. Improvement in the interpersonal communication skills of dental students. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, C.R. Empathic: An Unappreciated Way of Being. Couns. Psycholog. 1975, 5, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Silverman, J.; Benson, J.; Draper, J. Marrying Content and Process in Clinical Method Teaching: Enhancing the Calgary–Cambridge Guides. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Patient-Centered Communication and Shared Decision Making. In Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis; Levit, L., Balogh, E., Nass, S., Ganz, P.A., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 91–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R.; Roethlisberger, F.J. Barriers and Gateways to Communication. Harvard Bus. Rev. 1991, 69, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.; Farson, R.E. Active Listening; Industrial Relations Center of the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo, N. Active Listening Techniques: 30 Practical Tools to Hone Your Communication Skills; Rockridge Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Broder, H.L.; Janal, M.; Mitnick, D.M.; Rodriguez, J.Y.; Sischo, L. Communication Skills in Dental Students: New Data Regarding Retention and Generalization of Training Effects. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 79, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, B.; Bertera, E.M.; Feimster, T.; Hollander, R.; Stroman, C. Adaptation of the Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS) to Dental Students. J. Dent. Educ. 2012, 76, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, N.A.M.; Yusof, Z.Y.M.; Shahidan, M.N.F.M. University of Malaya Dental Students’ Attitudes towards Communication Skills Learning: Implications for Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, V.; Stoykova, M.; Semerdjieva, M. Communication Skills Teaching Methods in Dental Education—A Review. Folia Med. 2021, 63, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, D.G.; Yusuf, H. Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R. Motivational Interviewing with Problem Drinkers. Behav. Psychother. 1983, 11, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, S.M.; Silverman, J.D. The Calgary—Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med. Educ. 1996, 30, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, J.; Kurtz, S.; Draper, J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl, B.; Moleni, T.; Burke, B.L.; Butters, R.; Tollefson, D.; Butler, C.; Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pat. Educ. Counsel. 2013, 93, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, E.D.; Wolderslund, M.O.; Kofoed, P.-E.; Gulbrandsen, P.; Poulsen, H.; Cold, S.; Ammentorp, J. Codebook for rating clinical communication skills based on the Calgary-Cambridge Guide. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdaman, A.; Ahmadpour, R.; Serajzadeh, M. Dental Consultation Communication Checklist: Translation and Validation of the Persian Version. J. Islam. Dent. Assoc. Iran 2015, 27, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sangappa, S.B.; Tekian, A. Communication Skills Course in an Indian Undergraduate Dental Curriculum: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 77, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theaker, E.D.; Kay, E.J.; Gill, S. Development and preliminary evaluation of an instrument designed to assess dental students’ communication skills. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 188, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sangappa, S.; Chacko, T.; Bhandary, S. Ensuring Student Competence in Essential Dental Consultation Communication Skills for Patient Care: Developing, Validating and Piloting a Comprehensive Checklist. World J. Dent. 2020, 10, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.M.; Stein, T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: The four habits model. Perm. J. 1999, 3, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveugele, M.; Derese, A.; Maesschalck, S.D.; Willems, S.; Driel, M.V.; Maeseneer, J.D. Teaching communication skills to medical students, a challenge in the curriculum? Pat. Educ. Counsel. 2005, 58, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Molsing, S.; Meyer, N.; Schepler, M. Early Clinical Experience and Mentoring of Young Dental Students—A Qualitative Study. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindlisbacher, F.; Davis, J.M.; Ramseier, C.A. Dental students’ self-perceived communication skills for patient motivation. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2017, 21, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

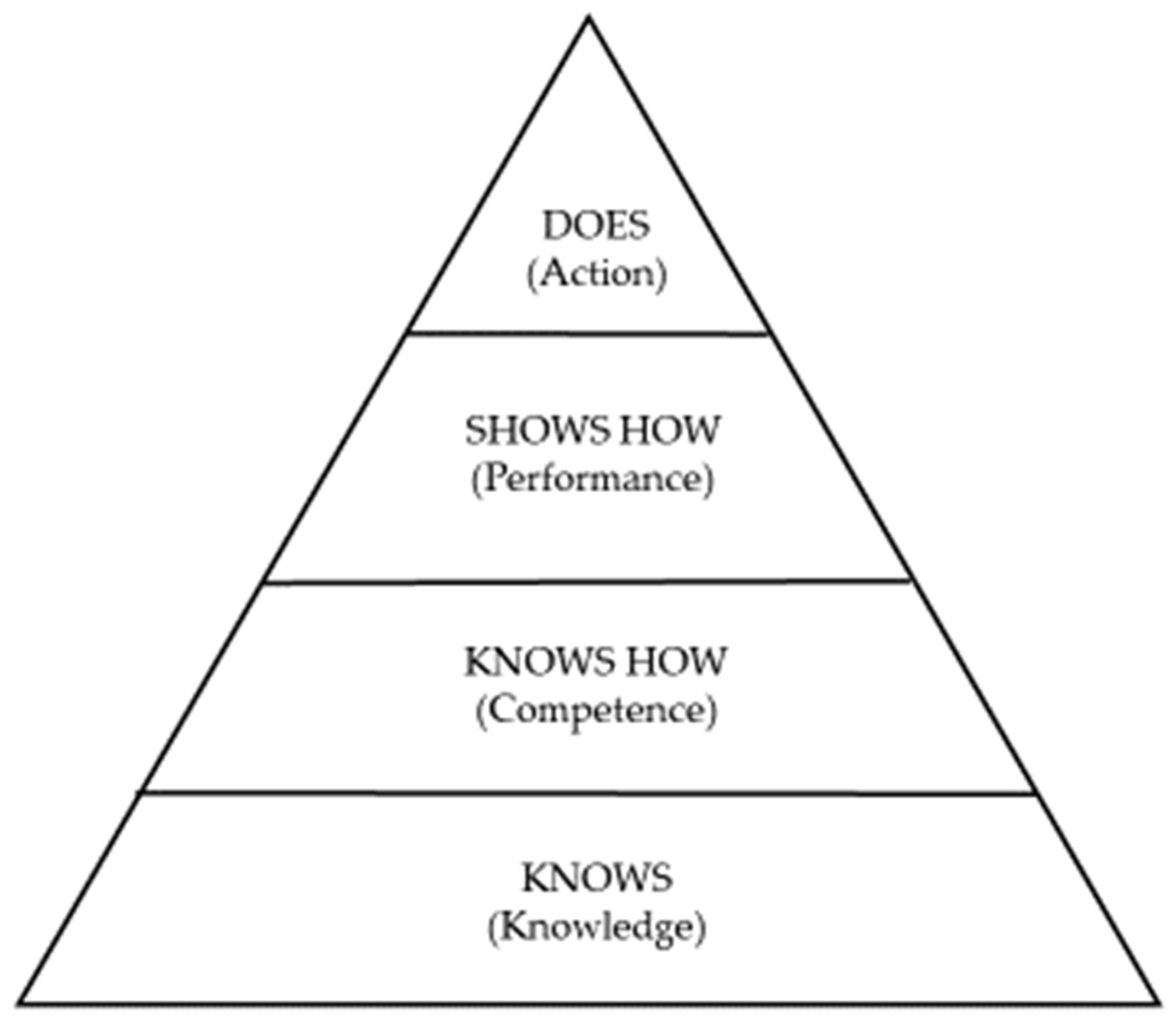

- Miller, G.E. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad. Med. 1990, 65, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Review Source n = 12 | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Special characteristics about the dental clinic relevant to learning communication skills | Khalifah & Celenza, 2019 Carey et al., 2010 |

|

| Cheng et al., 2015 |

| |

| Essential components of dental student learning communication skills | Khalifah & Celenza, 2019 |

|

| Scambler et al., 2016 |

|

| Mills et al., 2014 |

| |

| King & Hoppe et al., 2013 |

| |

| Khalifah & Celenza, 2019 |

|

| Carey et al., 2010 |

| |

| Burkert, 2021 |

|

| Ayn et al., 2017 |

| |

| Clinical consultation guides used in communication skills learning | Buduneli, 2020 Kalifah & Celenza, 2019 |

|

| Gillam & Yusuf, 2019 |

| |

| Gao et al., 2014 |

| |

| King & Hoppe, 2013 |

| |

| Optimal curricular structure for effective learning of clinical communication skills | Khalifah & Celenza, 2019 |

|

| Rütterman et al., 2017 |

| |

| Ayn et al., 2017 |

Assessments that are similar in nature to those of other clinical competencies might improve perceived importance of CST. |

| Skill Level Representing Multiple Micro-Skills | Corresponding C–CG Domains |

|---|---|

| (1) Identifies problems the patient wishes to address. | Initiating the session |

| (2) Clarifies patient’s prior knowledge and desire for information. | Gathering information |

| (3) Uses easily understood language, avoids jargon. | Gathering information |

| (4) Uses appropriate (supportive) non-verbal behavior. | Building a relationship |

| (5) Provides support: expresses concern and willingness to help. | Building a relationship |

| (6) Structures the interview in logical sequence. | Providing structure |

| (7) Attends to passage of time and keeps the interview on track. | Providing structure |

| (8) Shares thoughts and reflections with the patient. | Explanation and planning |

| (9) Checks patient’s understanding. | Explanation and planning |

| (10) Negotiates a mutual plan of action. | Explanation and planning |

| (11) Contracts with patient about the next steps. | Closing the session |

| (12) Summarizes session briefly and clarifies plan with patient. | Closing the session |

| Action: | Corresponding Domains: |

|---|---|

| (1) Greet the patient. | Investing in relationship |

| (2) Introduce yourself and that you are prepared to listen. | Investing in relationship |

| (3) Ask patient to explain reason for visit from own perspective. | Investing in relationship |

| (4) Explain what will happen during the visit; no jargon. | Investing in relationship |

| (5) Be ready to reformulate questions with patient confusion. | Gathering information |

| (6) Handle personal questions sensitively: What has patient heard? | Gathering information |

| (7) Explain what you want to do and why before you do it. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (8) Check patient comfort before examination. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (9) Explain findings without technical language. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (10) Reassure patient if necessary and use X-rays, other aids. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (11) Negotiate a mutual plan of action and next steps. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (12) Check patient understanding. | Examination/Explanation/Planning |

| (13) Point out that conversation is coming to an end. | Investing in closure |

| (14) Summarize session briefly; invite further questions/concerns. | Investing in closure |

| (15) Explain what will happen next; make new appointment. | Investing in closure |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moore, R. Maximizing Student Clinical Communication Skills in Dental Education—A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj10040057

Moore R. Maximizing Student Clinical Communication Skills in Dental Education—A Narrative Review. Dentistry Journal. 2022; 10(4):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj10040057

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoore, Rod. 2022. "Maximizing Student Clinical Communication Skills in Dental Education—A Narrative Review" Dentistry Journal 10, no. 4: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj10040057

APA StyleMoore, R. (2022). Maximizing Student Clinical Communication Skills in Dental Education—A Narrative Review. Dentistry Journal, 10(4), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj10040057